Abstract

A common treatment of advanced prostate cancer involves the deprivation of androgens. Despite the initial response to hormonal therapy, eventually all the patients relapse. In the present study, we sought to determine whether dietary polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) affects the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cell culture, patient tissue microarray, allograft, xenograft, prostate-specific Pten knockout and omega-3 desaturase transgenic mouse models in conjunction with dietary manipulation, gene knockdown and knockout approaches were used to determine the effect of dietary PUFA on castration-resistant Pten-null prostate cancer. We found that deletion of Pten increased androgen receptor (AR) expression and Pten-null prostate cells were castration resistant. Omega-3 PUFA slowed down the growth of castration-resistant tumors as compared with omega-6 PUFA. Omega-3 PUFA decreased AR protein to a similar extent in tumor cell cytosolic and nuclear fractions but had no effect on AR messenger RNA level. Omega-3 PUFA treatment appeared to accelerate AR protein degradation, which could be blocked by proteasome inhibitor MG132. Knockdown of AR significantly slowed down prostate cancer cell proliferation in the absence of androgens. Our data suggest that omega-3 PUFA inhibits castration-resistant prostate cancer in part by accelerating proteasome-dependent degradation of the AR protein. Dietary omega-3 PUFA supplementation in conjunction with androgen ablation may significantly delay the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer in patients compared with androgen ablation alone.

Introduction

The PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted from chromosome 10) tumor-suppressor gene encodes a phosphatidylinositol phosphatase (1). PTEN mutations were found in ∼15% of primary prostate cancer samples (2), and loss of PTEN expression was found in 50% of advanced primary prostate cancer (3). Heterogeneously distributed PTEN deletion was observed in 23% of hormone-sensitive and 52% of hormone-refractory prostate cancers (4). PTEN is one of the most frequently mutated genes in metastases of prostate cancer, occurring in at least one metastatic site in 12 of 19 (63%) patients who had multiple metastases (5) and in 9 of 15 (60%) cell lines and xenografts primarily derived from metastases of prostate cancer (6). Deletion of PTEN was reported to be associated with poor clinical outcome (7,8). Homozygous deletion of Pten in the mouse prostate results in prostate cancer development and metastasis (9).

A common treatment of prostate cancer, especially in advanced cases, involves the deprivation of androgens, clinically known as androgen ablation. Despite the initial response to hormonal therapy, nearly all of the patients experience disease relapse (10,11). Therefore, the development of castration resistance is a critical concern in the management of prostate cancer. Interestingly, an association between the loss of PTEN and the emergence of castration-resistant tumors was observed in patients (4) and in Pten knockout mouse models (12,13).

A large body of epidemiological and preclinical literature supports important roles for various types of dietary fat in modulating the cancer phenotype (14). Yet, the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of fat on cancer initiation and progression remain largely undefined. Consumption of fish or fish oil reduces prostate cancer incidence (15,16). One of the largest studies involving 6272 men during 30 years of follow-up suggests that fatty fish consumption is associated with decreased risk of prostate cancer (16). The serum level of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) was reported to be significantly decreased in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer and that of omega-6 PUFA was increased in patients with prostate cancer (17). In a prospective study of 47 882 men participating in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, higher consumption of fish was strongly associated with a reduced risk of metastatic prostate cancer (18). Using prostate-specific Pten knockout mice and diets with defined PUFA levels, we have shown previously that omega-3 PUFA reduces prostate tumor growth, slows histopathological progression and increases tumor-bearing animal survival, whereas omega-6 PUFA has the opposite effects (19). In the present study, we sought to determine whether dietary PUFA can affect the development of Pten-null castration-resistant prostate cancer in mice.

Materials and methods

Transgenic mice

Prostate-specific Pten knockout and fat-1 transgenic mice were generated as described previously (19). Histopathological evaluation of mouse prostate tissues was performed by a board certified veterinary pathologist.

All animals were maintained in an isolated environment in barrier cages and fed the specified diet. Animal care was conducted in compliance with the state and federal Animal Welfare Acts and the standards and policies of the Department of Health and Human Services. The protocol was approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell isolation and determination of androgen dependency

Pten−/−, Pten+/− and Pten+/+ mouse prostate epithelial cells were isolated from anterior prostates of 8 to10-week-old mice (19) as described previously (20). Cells were clonally selected using a serial dilution method (21) and Pten status was confirmed by genotyping and western blotting. To test for androgen dependence, cells (1 × 104) were incubated with regular complete medium for 24 h. Cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline twice and then incubated with phenol red-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 1% charcoal stripped fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus various amounts of R1881 (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Cells were counted daily for 6 days. Three independent experiments were performed.

Pten knockdown and knockout in vitro

Pten+/+ mouse prostate epithelial cells were infected with lentivirus expressing Pten targeting short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (GAA CCT GAT CAT TAT AGA TAT T) or control shRNA (GGG CCA TGG CAC GTA CGG CAA G). Infected cells were clonally selected using a serial dilution method (21) and confirmed by enhanced green fluorescent protein tag and western blotting of Pten. PtenL/L cells were isolated from anterior prostates of 8-week-old Pten floxed mice. In vitro deletion of Pten was achieved by infecting PtenL/L cells with a self-deleting Cre recombinase lentivirus (22). Cells were clonally selected using a serial dilution method and Pten status was confirmed by genotyping and western blotting.

Allografts

For the initial tumorigenicity assessment, 6 to 8-week-old male nude mice (NU/NU, strain code 088) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Mice were castrated or sham operated. One week after castration, 2 × 105 mouse Pten−/− or Pten+/+ cells mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were inoculated subcutaneously in pairs into each flank of castrated and non-castrated mice. Mice were terminated 3.5 weeks after tumor cell inoculation. For dietary PUFA experiments, 6 to 8-week-old male nude mice were randomly assigned to either omega-6 or omega-3 PUFA diet group and castrated a week later. One week after castration, 5 × 104 mouse Pten−/− cells mixed with equal volume of Matrigel were inoculated subcutaneously into each flank of mice. Tumor volume was measured twice a week and calculated with the formula: volume = 0.5236 × length × width2 (13). Mice were euthanized 6.5 weeks after tumor cell inoculation. Tumors were harvested and weighed.

Transgenic mouse models

Two feeding schemes were used in our experiments. Prostate-specific Pten knockout mice were on chow until 2 months of age, castrated and then switched to omega-6 or omega-3 PUFA diet. Alternatively, mice were fed omega-6 or omega-3 PUFA diets after weaning, castrated at 2 months of age and continued on their respective diet after castration. Blood and prostate tissues were harvested when mice were euthanized at the age of 6 months.

Diet

Diets were prepared by the custom animal diet laboratory of the Animal Resources Program at Wake Forest University. The diets used were an omega-6 diet, based on a typical American diet consisting of an omega-6 to omega-3 ratio of 40:1, 397 kcal/100 g with 30% of energy from fat, 50% from carbohydrates and 20% from proteins, and an isocaloric omega-3 diet, which has a ratio of 1:1 (19). Because essential fatty acids cannot be completely removed from diet, we consider the omega-6 diet as a control for the omega-3 diet.

Fatty acid and phospholipid analysis

Fatty acid and glycerophospholipid analyses were performed as described previously (19).

Androgen measurement

Hundred microliter of plasma was added to 900 μl of water followed by 116 pg of D3-testosterone in 2 ml of ethyl acetate. Samples were mixed by vortexing and then rotated for 1 h at 4°C. The organic layer was removed and then dried under argon. After suspending the residue in 200 μl of methanol, the sample was transferred to a conical autosampler vial. Methanol was removed in a stream of argon and the residue resuspended in 50 μl of the liquid chromatograph injection solvent: H2O:MeOH 90:10, 0.1% formic acid. Samples were processed on a Symbiosis Pharma™ System from Spark Holland and then analyzed on a Waters Quattro II triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Sample vials were kept at 15°C before injection. Twenty-five microliter sample aliquots were processed through Hysphere C18 (EC) cartridges. The eluted samples were separated at 40°C on a 2.1 × 50 mm Phenomenex Kinetex C18 column packed with 2.6 micron diameter particles having 100 Å pores. Running solvents for gradient liquid chromatograph separation were solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water and solvent B was pure methanol. Separation was conducted at 100 μl/min with the following gradient: 100% A to 90% B at 10 min, hold at 90% B for 5 min and then back to 100% A at 16 min followed by a 14 min equilibration at 100% A. Column effluent was introduced into the Z-spray electrospray source of the mass spectrometer operated in the positive ion mode with a cone voltage of 35 V using selective reaction mode to monitor the following ion pairs: D3 testosterone, 292.2 > 97.1 with a collision energy (CE) = 23 V; testosterone, 289.2 > 97.1 with CE = 23 V; dihydrotestosterone, 291.2 > 255.1 with CE = 18 V; and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), 289.2 > 253.1 + 271.2 > 253.1 with CE = 12 V. Standard curves for testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and DHEA were prepared from 25 to 500 pg per sample with 116 pg per sample D3-testosterone as the internal standard. Results are shown in ng/ml of plasma.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was performed with a rabbit anti-Ki67 antibody (cat# ab15580, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), a rat anti-CD45R antibody (ab64100, Abcam) and a rabbit anti-Factor VIII antibody (cat# 18-0018, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All primary antibodies were incubated at 4°C overnight, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (cat# K4010, Dako, Carpinteria, CA); however, rat anti-CD45R antibody was followed first by a rabbit anti-rat IgG (Cat# 312005003, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) then by the horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody. All sections were visualized with DAB substrate (Dako). Total number and positively stained epithelial cells were enumerated using 20-fold magnified photographs from four areas of each section with the Image-Pro Plus 4.5 software (Image Processing Solutions, North Reading, MA). The Ki67 and CD45R staining was expressed as percentage of positive cells per hundred epithelial cells. The number of blood vessels stained by Factor VIII was manually counted by two individuals.

Phospho-AktS473/androgen receptor analysis in patient samples

A large cohort of men with prostate cancer who are participants in the Physicians’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study was assessed for the association between tumor expression of phospho-AktS473 (pAktS473) and androgen receptor (AR) using immunohistochemical methods. The cases were included on ten tissue microarrays, aimed to include at least three 0.6 mm cores of tumor per case. Quantitative assessment of the markers was performed on the Ariol Image analysis system (Genetix Corp., San Jose, CA). pAktS473 staining was divided into quartiles based on the distribution of percent of positive staining cells in the whole cohort. Generalized linear models were used to estimate the mean and standard error of staining intensity for AR in tumors across categories of pAktS473. The ordinal variable of pAktS473 quartiles was modeled to estimate a P value for trend.

Western blotting

Prostate tissues were homogenized or cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride buffer with 1X protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors (Cat#1697498 and 04906837001, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Western blotting was performed as described previously (19) with anti-Pten (cat# 9559), anti-pAktT308 (cat#2965), anti- pAktS473 (cat# 3787), anti-total Akt (cat# 9272) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti-androgen receptor (cat# sc-816), anti-Lamin B1 (cat# sc-20682), anti-GFP (cat#sc-8334) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) as well as anti-β-actin (cat# A5441, Sigma) and anti-α-tubulin (cat#MCA77G) (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC). The density of bands from western blots was quantified using AlphaView software (ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA).

PUFA treatment

Pten-null human prostate cancer cells LNCaP and C4-2, a castration-resistant clone of LNCaP, as well as mouse prostate epithelial cells were maintained in advanced DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% FBS. Cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline twice and then incubated with phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 1% charcoal stripped FBS plus bovine serum albumin (BSA), 60 μM of BSA-conjugated arachidonic acid (AA) or docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) for 24–72 h.

Cytosolic and nuclear fractionation

Cells were first lysed in a lysis buffer [10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid pH 7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% CA630, 1X protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4]. Nuclei were pelleted at 1000g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant was retained as the cytosolic fraction. After rinsing pellets with the lysis buffer twice, nuclear protein was extracted in a nuclear buffer (20 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid pH 7.9, 420 mM NaCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 mM ethyleneglycol-bis(aminoethylether)-tetraacetic acid, 20% glycerol, 1X protease and phosphatase inhibitor, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4) with 3 × 3 s sonication at setting 10 in a Misonix XL-2000 sonicator (Qsonica, LLC, Newtown, CT).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted using TRIZOL (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed with Superscript III Plus RNase H-Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed with Platinum SYBR Green qPCR Supermix UDG (Invitrogen) on Bio-Rad iCycler (Hercules, CA). The primers used were forward primer AAA TGG TGA AGG TCG GTG TG and reverse primer CGT TGA ATT TGC CGT GAG for GAPDH and forward primer ATT GCC CAT CTT GTC GTC TC and reverse primer CTG CCA GCA TTG GAG TTT for AR.

AR protein stability assay

C4-2 cells were incubated in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 1% charcoal stripped FBS plus BSA, 60 μM AA or 60 μM DHA for 72 h and then cycloheximide (Sigma) or MG132 (Sigma) was added at the final concentration of 20 μg/ml or 10 μM. Cells were harvested after 1 or 2 h incubation and used for western blot analysis.

AR knockdown and proliferation assays

C4-2 human prostate cancer cells were infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA or the AR targeting shRNA (GAG GCA CCT CTC TCA AGA GTT) (23). Infected cells were confirmed by enhanced green fluorescent protein tag and western blotting of AR.

For proliferation in culture, cells (6 × 104) were seeded onto 6 well plates in phenol red-free DMEM with 1% charcoal stripped FBS plus BSA or 60 μM DHA. Cells were counted after 24 h incubation and then counted every other day for 7 days. Two independent experiments were performed. For proliferation in vivo, 10 nude mice were fed with the omega-3 PUFA diet. All mice were castrated after 1 week on the diet. 5 × 105 AR shRNA or scrambled shRNA-infected C4-2 cells were mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel and inoculated subcutaneously into each flank of mice 2 weeks after castration. Tumor volume was measured once a week. Mice were euthanized 6 weeks after cancer cell inoculation.

Statistics

Quantitative data with two groups were tested by unpaired Student's t-test using Excel software (Microsoft, Seattle, WA). Quantitative data of over two groups were initially evaluated by analysis of variance followed by Tukey test to evaluate pairwise comparisons using GraphPad Software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

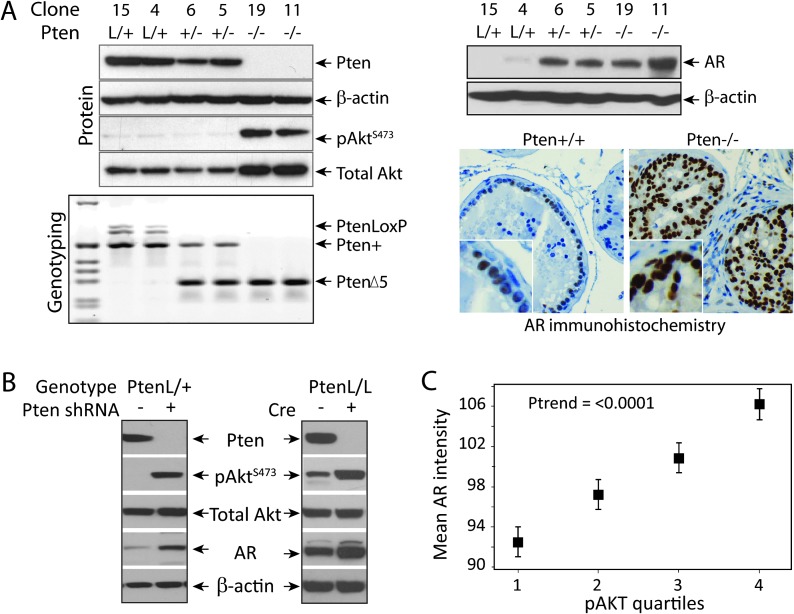

The Pten/Akt pathway affects AR levels in prostate tumor cells

An association between the loss of PTEN and emergence of castration-resistant tumors was observed in patients (4) and in Pten knockout mouse models (12,13). Since the AR signaling pathway may play a role in castration resistance, AR expression was compared in Pten wild-type and Pten-null prostate cells. Prostate epithelial cells were isolated from mice with the following genotypes: PtenL/L, CreT (equivalent to prostate-specific Pten−/−); PtenL/+, CreT (Pten+/−) and PtenL/+, Cre− (Pten+/+) (Figure 1A). Interestingly, the level of AR protein was increased in Pten−/− and, to lesser extent, Pten+/− compared with Pten+/+ cells (Figure 1A). To confirm this inverse correlation between Pten and AR, Pten expression was knocked down in the Pten+/+ cells using Pten-specific shRNA or the Pten gene was deleted in vitro by Cre expression in PtenL/L cells. In either case, loss of Pten increased AR expression (Figure 1B). It is well known that deletion of PTEN activates Akt. Active Akt (pAktS473) and AR proteins were assessed by IHC in a large cohort of prostate cancer patient samples from the Physicians’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study. A significant positive association was found between prostate tumor expression of pAktS473 and expression of AR (P for trend < 0.001) (Figure 1C). Men in the top quartile of pAktS473 in their tumors had a 20% increase in expression of AR compared with those in the bottom quartile of pAktS473 staining. Therefore, in vitro, animal and patient data collectively indicate that the Pten/Akt pathway affects AR levels in prostate tumor cells.

Fig. 1.

Effect of the Pten/Akt pathway on AR levels. (A) Pten deletion in vivo: Pten+/+, +/− and −/− prostate epithelial cells were established from 8- to 10-week-old anterior prostate of PtenL/+, Cre−; PtenL/+, CreT; and PtenL/L, CreT mice, respectively. Pten status was confirmed by genotyping and PTEN and AKT protein expression by western blotting. AR protein expression was analyzed by western blotting in cell lines and by IHC in tissues. Deletion of Pten increased AR expression. (B) Pten knockdown in vitro: Pten+/+ cells were treated with control or Pten shRNA. PtenL/L cells were infected with Cre recombinase lentivirus and three independent clones were selected. PTEN, AKT and AR expression was determined by western blotting. In vitro Pten knockdown and knockout increased AR expression. (C) Human prostate tissues: the association between tumor expression of phospho AKT and AR was assessed by IHC and mean pAktS473 expression was placed in quartiles based on percentage positive staining. Expression of pAktS473 significantly correlated with the expression of AR (P for trend < 0.001).

Pten-null prostate tumor cells are castration resistant

To assess their androgen responsiveness, Pten+/+ and Pten−/− prostate cells were grown in culture or as allografts in the presence or absence of androgens. Pten+/+ cells did not proliferate in charcoal stripped medium nor did they respond to R1881, a synthetic androgen analog. However, Pten−/− cells could proliferate slowly in charcoal stripped medium and more rapidly in response to R1881 (Supplementary Figure 1A is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Pten+/+ cells also did not grow in castrated or intact male nude mice as allografts. In contrast, Pten−/− cells formed tumors in both castrated and intact male nude mice (Supplementary Figure 1B is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Thus, Pten-null prostate tumor cells are androgen responsive and castration resistant.

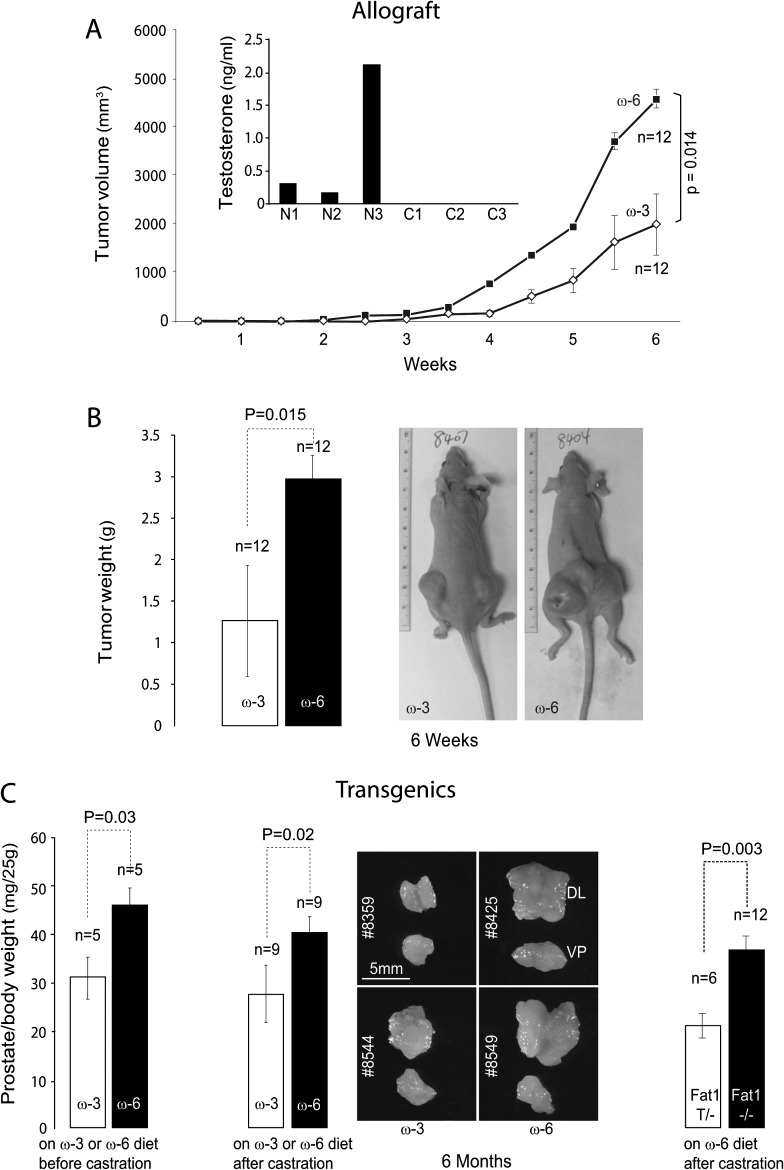

Omega-3 PUFA slows down the growth of castration-resistant tumors

To determine the effects of diet on the growth of castration-resistant prostate cancer allografts, 8-week-old nude mice were placed on the omega-3 or omega-6 diet 1 week before undergoing castration and then inoculated with Pten−/− cells 1 week after surgery. Tumors were measured for volume weekly and then dissected and weighed 6 weeks after cell inoculation. Allografts from mice on the omega-3 diet grew to less than half the average volume (Figure 2A) and weight (Figure 2B) of those on the omega-6 control diet.

Fig. 2.

Differential effect of omega-3 and omega-6 PUFA on the development of castration-resistant prostate tumors. (A)Tumor volume in allograft model: Pten−/− cells were inoculated in castrated mice as described earlier. Plasma testosterone level was measured and confirmed the success of castration (N1–N3: non-castrated, C1–C3: castrated). Mice were fed omega-3 or omega-6 diet (6 mice and 12 allografts per group). Tumor volumes were monitored twice a week. Compared with omega-6 diet group, omega-3 diet slowed down the growth of castration-resistant tumors significantly (6-week data point, P = 0.014, Student's t-test). (B) Tumor weight in allograft model: at the end of 6 weeks, tumors were dissected and weighed. Compared with omega-6 diet group, omega-3 diet reduced the weight of castration-resistant tumors significantly (P = 0.015, Student's t-test). Pictures of representative tumor-bearing nude mice are shown. (C) Tumor weight in transgenic model: prostate-specific Pten knockout mice were placed on omega-3 or omega-6 diet after weaning, castrated at the age of 2 months and terminated at the age of 6 months (left panel, five mice per group). Alternatively, prostate-specific Pten knockout mice were placed on chow diet for 2 months to allow tumor formation and then castrated and fed omega-3 or omega-6 diet for 4 months (middle panel, nine mice per group). Compared with omega-6 diet group, omega-3 diet significantly delayed the development of castration-resistant tumors. Finally, fat-1 transgene was bred into the prostate-specific Pten knockout genetic background. Mice with or without fat-1 were placed on chow diet for 2 months and then on omega-6 diet after castration (right panel, 6–12 mice per group). Significantly, smaller prostate tumors were seen in fat-1 transgenic mice compared with the littermate controls (P = 0.003, Student's t-test).

Androgens, namely testosterone (T), dihydrotestosterone and DHEA were also measured in the plasma. Non-castrated male mice had variable levels of T, which is consistent with a previous report (24). As expected, castrated mice had no detectable levels of T (Figure 2A). In fact, no T, DHT or DHEA were detectable in castrated mice on either omega-3 or omega-6 diet.

To more closely model the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer in patients, we used prostate-specific Pten knockout mice. In an initial experiment, Pten−/− mice were placed on omega-3 or omega-6 diet at weaning (3 weeks of age), castrated at the age of 2 months and terminated at the age of 6 months. Mouse prostates were dissected and weighed. Castration-resistant tumors developed in all mice, but were 30% smaller in mice on the omega-3 compared with the omega-6 control diet (Figure 2C, left panel). Since PUFA also affects primary prostate tumor growth (19), prostate-specific Pten knockout mice were fed chow diet prior to castration to allow tumor formation under the same condition for both groups, then castrated at 2 months of age and subsequently fed the omega-3 or omega-6 diet for 4 months. Mouse prostates were dissected and weighed at 6 months of age. A similar reduction in castration-resistant prostate tumor weights was observed in mice on the omega-3 compared with mice on the omega-6 control diet (Figure 2C, middle panel).

In addition, to confirm that omega-3 PUFA is responsible for the observed effect on prostate tumor growth, the fat-1 transgene (14), encoding an omega-3 desaturase from Caenorhabditis elegans that converts omega-6 into omega-3 fatty acids (19), was bred into the prostate-specific Pten knockout genetic background. Mice with or without the fat-1 transgene were both maintained on chow diet for 2 months and then switched to the omega-6 diet after castration. Significantly, smaller prostate tumors were observed in fat-1 transgenic mice compared with the littermate controls (Figure 2C, right panel). Data from all three models (allograft, Pten−/− and Pten−/−; fat1T) indicate that omega-3 PUFA slows down compared with omega-6 PUFA, the growth of castration-resistant prostate tumors.

Dietary PUFA is efficiently incorporated into tumor tissues

To assess the efficiency of dietary PUFA intake, fatty acid profiles were analyzed in allografts and prostate tissues from Pten−/− mice on omega-3 and omega-6 diets. Total fatty acid measurements indicate that tumors from mice on the omega-3 diet contained substantially higher levels of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA 20:5n-3), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA 22:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA 22:6n-3), whereas higher levels of linoleic acid (LA 18:2n-6) and arachidonic acid (AA 20:4n-6) were found in tumors from mice on the omega-6 diet (Supplementary Figure 2A is available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Dietary PUFA was incorporated into glycerophospholipids. Tissues from mice on omega-3 diet had high amounts of eicosapentaenoic acid- and DHA-containing phosphatidylcholine (16:0, 20:5; 16:0, 22:6 and 18:0, 22:6), phosphatidylethanolamine (16:0, 20:5; 16:0, 22:6; 18:0, 22:6 and 18:1, 22:6), phosphatidylinositol (18:0, 20:5; 20:0, 20:5; 16:0, 22:6 and 18:0, 22:6) and phosphatidylserine (20:0, 20:5; 18:0, 22:6). In contrast, tissues from mice on omega-6 diet had high amounts of AA-containing phosphatidylcholine (16:0, 20:4; 18:0, 20:4 and 20:0, 20:4), phosphatidylethanolamine (16:0, 20:4; 18:0, 20:4 and 20:0, 20:4), phosphatidylinositol (16:0, 20:4; 18:0, 20:4 and 20:0, 20:4) and phosphatidylserine (18:0, 20:4; 20:0, 20:4) (Supplementary Figure 2B is available at Carcinogenesis Online).

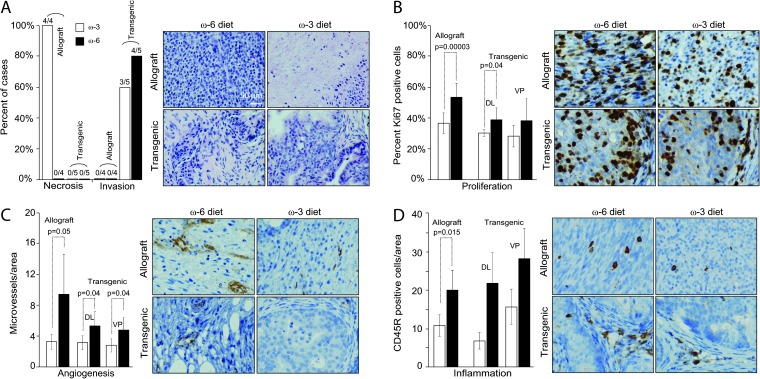

Omega-3 PUFA, compared with omega-6 PUFA, reduces tumor pathological progression, proliferation, angiogenesis and inflammation

In allografts, all tumors from mice fed the omega-3 diet for 6 weeks had >10% of necrotic areas, whereas none of the tumors from mice fed the omega-6 diet had any necrosis at this time point (Figure 3A). In transgenic mice, no necrosis was detected in tumors from mice fed either the omega-3 or omega-6 diet for 6 months (Figure 3A). Allografts were well-circumscribed nodules composed of fusiform cells with no obvious invasion of the surrounding tissues. However, most of the castration-resistant tumors in transgenic mice invaded into the surrounding tissues at 6 months of age regardless of diet type (Figure 3A).

Fig. 3.

Tumor tissue response to dietary PUFA in castrated mice. (A) Necrosis and invasion: histology of tumor tissues from allografts or transgenics fed omega-3 and omega-6 diets was evaluated by a veterinarian pathologist. Any invasive cancer or necrosis (>10% of area) observed in either lobe of prostate was considered positive. The rate was expressed as the ratio of positive mice to total number of mice examined. (B) Proliferation: percent of proliferating cells was examined using Ki67 as a marker. Compared with omega-6 diet group, omega-3 diet reduced the fraction of proliferating cells in allografts (P = 0.00003, Student's t-test) and in dorsolateral (DL) prostate (P = 0.04, Student's t-test). Note: there were no obvious structures for anterior prostate or seminal vesicles in castrated mice. (C) Angiogenesis: microvessel density was quantified. Compared with omega-6 diet group, omega-3 diet reduced angiogenesis in both allografts and transgenics. (D) Inflammation: tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were quantified using CD45R as marker. Compared with omega-6 diet group, omega-3 diet reduced inflammation in allografts (P = 0.015, Student's t-test). A similar trend was seen in transgenics but failed to reach statistical significance.

As mentioned above, the Pten−/− allografts had fusiform or mesenchymal morphology. Pten−/− epithelial cells, after propagation in culture, acquired changes resembling an epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Cells exhibited elongated morphology were negative for E-cadherin and pan-cytokeratin but expressed N-cadherin (Chen unpublished results). To further substantiate that these changes are associated with the loss of the Pten, PtenL/L prostate epithelial cells were isolated, infected with Cre-expressing lentivirus in culture and Pten−/− clones were obtained. Long-term culture of the in vitro deleted Pten−/− cells led to similar changes (data not shown).

Previously, we found an increase in apoptosis in primary Pten-null prostate tumors from mice fed omega-3 diet compared with omega-6 diet (19). In the present study of castration-resistant tumors, however, there were no significant differences in apoptosis based on cleaved caspase-3 IHC staining between tumors from mice fed the omega-3 and omega-6 diets (data not shown). Instead, tumors from mice fed the omega-3 diet had smaller proliferative populations compared with mice fed the omega-6 control diet (Figure 3B).

Tumors from mice fed the omega-3 diet also had lower microvessel densities compared with mice fed the omega-6 control diet (Figure 3C). A majority of vessels were located in the prostate stroma in transgenic tumors, whereas microvessels in allografts were spread throughout the tumors (Figure 3C).

Tumors from transgenic mice had significant infiltration of CD3+ T and CD45R+ B lymphocytes. Nude mice (NU/NU, strain code 088) are deficient in producing T lymphocytes, however, are capable of generating B lymphocytes. Interestingly, CD45R+ B lymphocytes were detectable in allograft tumors. The number of CD45R+ cells was smaller in tumors from both transgenic and allograft mice fed the omega-3 diet compared with mice fed the omega-6 control diet (Figure 3D).

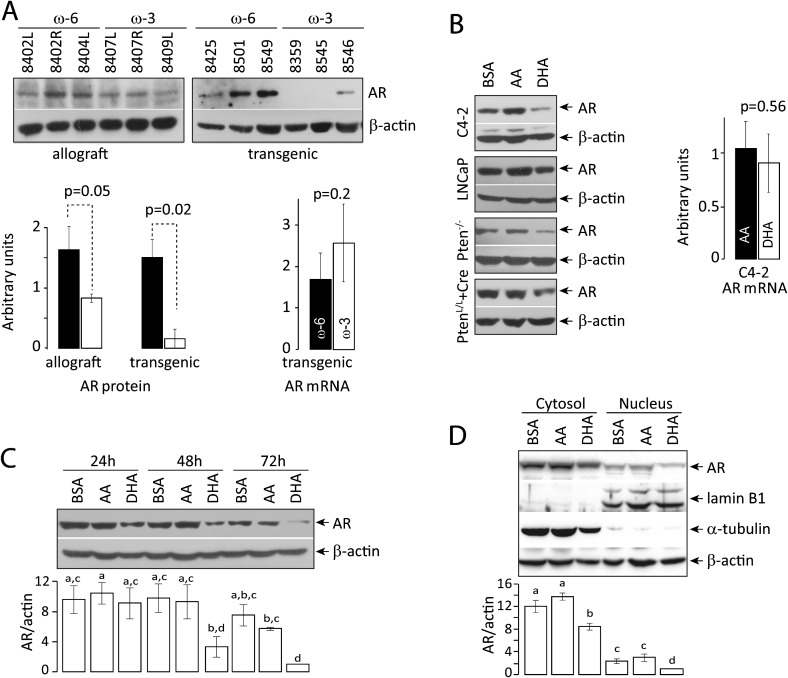

Omega-3 PUFA reduces AR protein level in castration-resistant tumor cells

Deletion of Pten increases AR expression, which may be partly responsible for the castration resistance of tumors. We asked whether omega-3 PUFA slows down the development of castration-resistant prostate tumor by affecting the AR signaling pathway. AR expression was examined in prostate tumors from mice on different diets. Tissues from transgenic mice on the omega-3 diet had significantly reduced levels of the AR protein compared with mice on the omega-6 diet (Figure 4A). A similar trend was observed in allograft tissues (Figure 4A) as well as Pten-null cells treated with DHA (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4.

Decrease in AR protein induced by omega-3 PUFA. (A) Effects in vivo: western blot of AR in prostate tumor tissues from allografts or transgenics fed omega-3 and omega-6 diets. Compared with omega-6 diet group, omega-3 diet reduced AR expression in transgenics (P = 0.02, Student's t-test). A similar trend was seen in allografts. Bars are standard deviations. AR messenger RNA was quantified by real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. No statistically significant difference was seen between tumor samples from mice on omega-3 and omega-6 diet. (B) Effects on multiple cell lines: human PTEN-negative prostate tumor cells (C4-2 and LNCaP), mouse Pten-null cells (Pten−/−) and in vitro Pten-deleted mouse prostate cells (PtenL/L+Cre) were incubated with AA, DHA or BSA. AR protein expression was determined by western blotting. AR messenger RNA in C4-2 cells was quantified by real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. DHA treatment reduced AR protein, but not messenger RNA levels. Bars are standard deviations. (C) Kinetics: C4-2 cells were treated with AA, DHA or BSA for 24, 48 and 72 h. AR protein expression was determined by western blotting. DHA treatment reduced the level of AR protein. (D) Subcellular distribution of AR protein: C4-2 cells were treated with AA, DHA or BSA for 72 h. Cytosolic and nuclear fractions were prepared and AR protein expression was determined by western blotting. Lamin B1 and α-tubulin were used as loading controls for nuclear and cytosolic fractions, respectively. DHA treatment reduced the level of AR protein to a similar extent in both fractions, suggesting that DHA had no effect on AR nuclear translocation. Analysis of variance was used to assess the significance of data. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

To understand better the mechanism of AR downregulation by omega-3 PUFA, AR messenger RNA was quantified by real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. No significant difference in AR messenger RNA levels was seen in prostate tissues from transgenic mice on either the omega-3 or omega-6 diet (Figure 4A) nor in cells treated with AA and DHA (Figure 4B). Instead, omega-3 PUFA appears to downregulate AR protein rather than messenger RNA. By 48–72h, DHA treatment significantly reduced the AR protein level compared with AA or BSA treatment (Figure 4C). To determine if the effect of DHA might be mediated in part by a change in subcellular distribution of AR, we determined AR protein levels in cytosolic and nuclear fractions isolated from BSA-, AA- or DHA-treated C4-2 cells (Figure 4D). DHA treatment reduced the levels of AR protein to a similar extent in both fractions, suggesting that DHA had no significant effect on nuclear translocation of the protein.

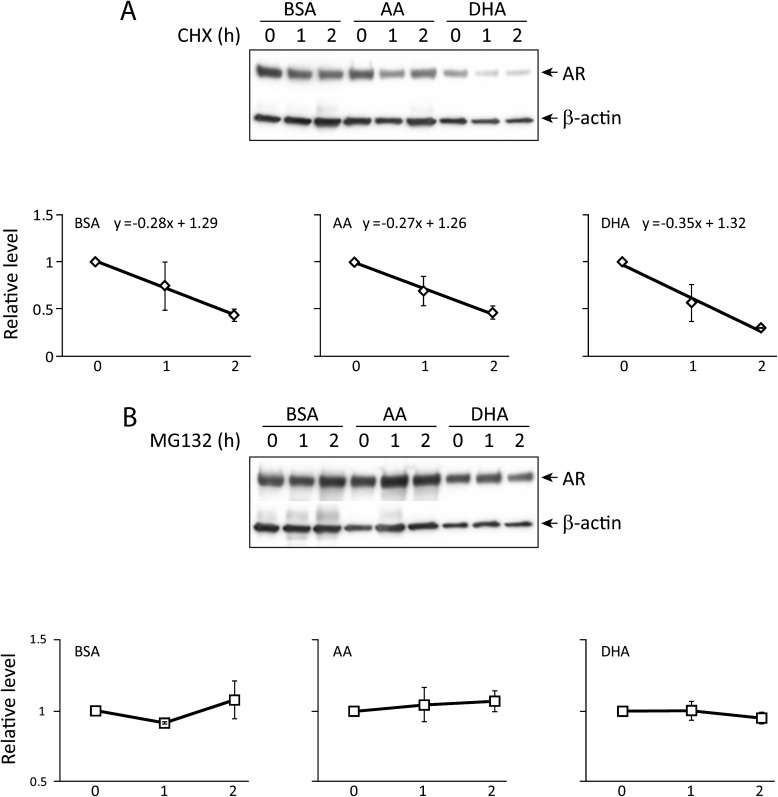

Omega-3 PUFA increases proteasome-dependent degradation of AR protein

To assess the AR protein degradation rate, C4-2 cells were treated with BSA, AA or DHA and then the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide. AR protein from BSA- and AA-treated cells had a similar degradation rate with slopes of −0.28 and −0.27, respectively. In DHA-treated cells, however, AR appeared to degrade faster with a slope of −0.35 (Figure 5A). AR protein degradation was proteasome dependent since incubation of BSA-, AA- or DHA-treated C4-2 cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 prevented the decline in AR protein level (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5.

AR protein stability. (A) AR protein degradation rate: C4-2 cells were treated with cycloheximide (20 μg/ml) after incubation with BSA, AA or DHA for 72 h. Cells were harvested at 0, 1 and 2 h and were analyzed by western blotting for AR levels. The curves and equations represented the rate of AR degradation in the absence of de novo protein synthesis. DHA treatment showed an increased rate of AR degradation. (B) Proteasome dependency: C4-2 cells were treated with proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM) after incubation with BSA, AA or DHA for 72 h. AR levels were determined at 0, 1 and 2 h after the addition of the inhibitor. MG132 prevented the decline in AR protein, suggesting that AR degradation is proteasome dependent.

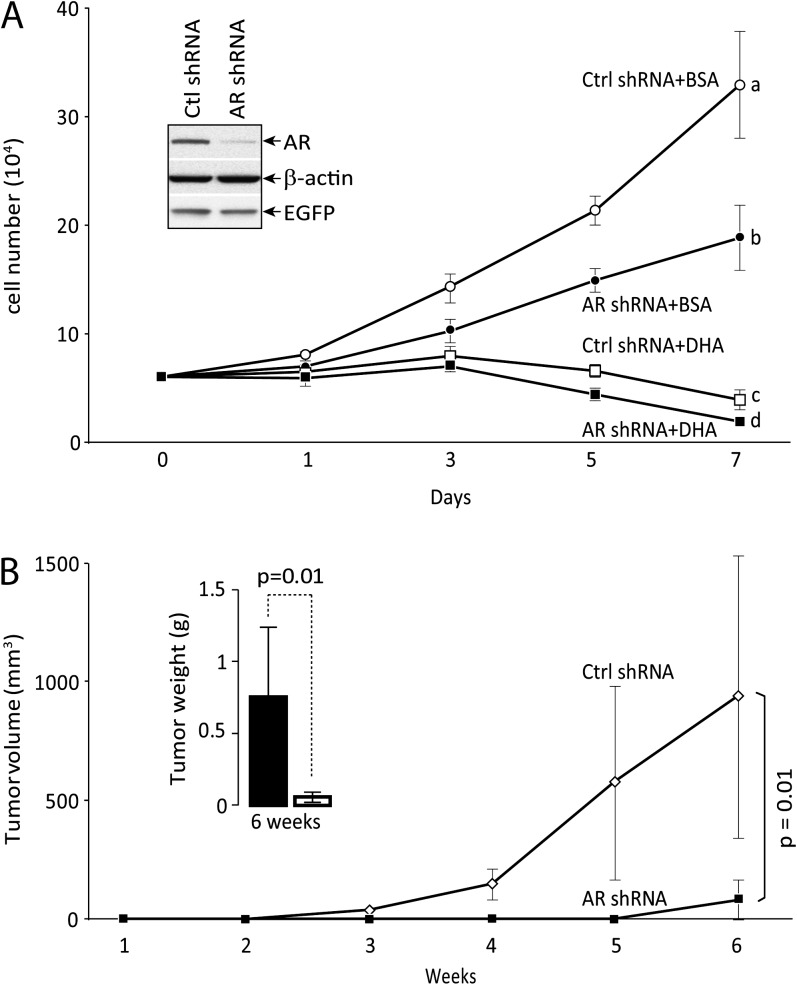

AR knockdown inhibits proliferation of castration-resistant tumor cells

To further demonstrate its role in castration resistance, AR was knocked down in C4-2 cells (Figure 6A) and cell proliferation was measured in the absence of androgens. AR knockdown significantly reduced cell proliferation in medium with charcoal stripped FBS. Cell proliferation was inhibited in medium with charcoal stripped FBS plus 60 μM DHA and AR knockdown further diminished cell proliferative capacity in culture (Figure 6A). AR knockdown also significantly reduced tumor growth in xenografts as measured by volume and weight (Figure 6B).

Fig. 6.

Effect of AR knockdown on cell proliferation. (A) In vitro proliferation: C4-2 cells were infected with control or AR shRNA lentivirus with enhanced green fluorescent protein marker. Successful knockdown was confirmed by western blot. Cells were incubated in medium with charcoal stripped FBS with BSA or DHA for indicated time. Knockdown of AR significantly slowed down cell proliferation in the medium containing BSA. DHA incubation completely inhibited and knockdown of AR further reduced cell proliferation. Analysis of variance analysis indicates that group a, b, c and d are statistically different (P < 0.05) at day 7. (B) In vivo proliferation: control or AR shRNA infected cells (5 × 105) were mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel, inoculated subcutaneously in pairs into flanks of castrated mice (n = 5) fed with omega-3 PUFA diet. Tumor volumes were monitored once a week and calculated. Mice were terminated at week 6 and tumor weights were determined. Knockdown of AR significantly inhibited tumor growth (P = 0.01, Student's t-test). Bars are standard deviations.

Discussion

Diet is a potential modulator of prostate cancer. Humans obtain omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs entirely from diet or dietary supplements (25). Epidemiological studies suggest that consumption of fish or fish oil reduces prostate cancer incidence (15,16), as determined by one of the largest studies following 6272 men over 30 years (16). Additionally, patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer were reported to have significantly decreased omega-3 and increased omega-6 PUFA levels in the serum compared with the control group (17). Therefore, omega-3 PUFA may be protective against prostate cancer development in patients.

Following our previous study on the influence of PUFA on prostate tumor development (19), we sought to determine whether dietary PUFA can also affect castration resistance of Pten-null prostate cancer. The data presented here indicate that the omega-3 diet slows down, compared with the omega-6 control diet, the growth of castration-resistant tumors. Consistent with our observation, a recent study showed that supplementation of the AIN-76A-based diet with a single omega-3 PUFA, eicosapentaenoic acid, significantly delays the androgen independent relapse of human prostate cancer xenografts (26). In addition to tumor weight, omega-3 and omega-6 PUFA also differentially affected the histology, proliferation, necrosis, angiogenesis, inflammation and possibly invasion of castration-resistant tumors (Figure 3). Necrosis was seen in tumors from allograft mice fed omega-3 diet, but not in tumors from transgenic mice, due perhaps to the larger mass of tumors in allografts compared with orthotopic prostate tumors in the transgenic mouse model. In primary Pten-null prostate tumors, omega-3 PUFA induced apoptosis in a Bad-dependent manner (19). In castration-resistant tumors, however, we detected no significant differences in apoptosis based on cleaved caspase-3 IHC staining between tumors from mice fed omega-3 and omega-6 diets. Instead, tumors from mice fed the omega-3 diet had smaller proliferative fractions compared with mice fed the omega-6 diet. This discrepancy in proliferation and apoptosis may be due, in part, to an altered cellular response of castration-resistant tumor since these tumor cells have undergone massive apoptosis after androgen withdrawal. We noticed that the number of CD3+ T and CD45R+ B lymphocytes was significantly reduced in the primary prostate tumors from transgenic mice fed the omega-3 compared with omega-6 diet (Chen unpublished results). In the case of castration-resistant tumors, a difference in CD45R+ B lymphocytes was observed (Figure 3D). Taken together with the recent observation that B-cell-derived lymphotoxin promotes castration-resistant prostate cancer (27), this suggests that omega-3 PUFA may act in part by reducing B lymphocytes in castration-resistant cancer.

Previously, it was believed that hormone-refractory prostate cancer was androgen independent and thus that the AR was dispensable. However, evidence suggests that AR is not only present in >90% of hormone-refractory prostate tumors (28,29) but also amplified or overexpressed in 50% of bone metastases (30) and in 20–30% of recurrent hormone-refractory prostate cancers (31–34). To more accurately describe this clinical condition, ‘castration resistant’ has recently replaced ‘hormone refractory’ or ‘androgen independent’. Interestingly, we observed an increase in the AR protein level in Pten-null prostate tumor cells (Figure 1A), which may explain the association between Pten loss and development of castration resistance. Indeed, AR knockdown significantly impaired the tumorigenesis of Pten-null prostate cells in female SCID mice (13). We demonstrated that omega-3 PUFA slowed down, compared with omega-6 PUFA, the growth of castration-resistant tumors, and this differential effect may be due, in part, to their effect on the level of AR proteins (Figure 4). A report suggests that omega-3 PUFA affects AR-dependent gene expression (35). We found that AR protein was similarly reduced in both the cytosolic and nuclear fractions. However, AR-dependent gene expression was not assessed. The reduction in AR proteins appears to be due to an increase in proteasome-dependent degradation.

A recent study suggests that castration-resistant growth is an intrinsic property of Pten-null prostate cancer cells. Loss of PTEN suppresses androgen-responsive gene expressions and deletion of Ar in mouse epithelium promotes the proliferation of Pten-null cancer cells (36). This seems to be difficult to reconcile with the fact that the vast majority of advanced prostate cancer cases are AR positive, a third of which have AR overexpression, and that up to 70% of advanced prostate cancer cells have deletion of PTEN. Our data show that knockdown or knockout of Pten increases AR protein expression in prostate epithelial cells (Figure 1) and Pten−/− cells are castration-resistant (Supplementary Figure 1 is available at Carcinogenesis Online). Knockdown of AR inhibits prostate Pten-null cell proliferation (Figure 6), suggesting a critical role of AR in castration resistance. It is possible that deletion of the Ar gene can select a population of castration-resistant tumor cells that is independent of AR.

Prostate cancer is usually diagnosed in aged men and tumor cell proliferation is typically slow. Preventing or slowing down the local regrowth of tumors and the development of castration-resistant lesions could significantly extend patient lives. Our data suggest that dietary omega-3 PUFA supplementation in conjunction with androgen ablation could significantly delay the development of castration-resistant Pten-null prostate cancer compared with androgen ablation alone. Furthermore, one prominent side effect of androgen ablation is osteoporosis, and higher omega-3 to omega-6 ratios have been linked to increased bone mineral density in older adults (37). Therefore, omega-3 PUFA may not only delay the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer but could also have a salutary effect on bone density in patients treated with hormonal ablation.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

American Institute for Cancer Research (07B087) and National Institutes of Health (R21CA124511, R01CA107668 and P01CA106742).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhiyong Deng and Meimei Wan for their technical assistance. Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AR

androgen receptor

- AA

arachidonic acid

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CE

collision energy

- DHEA

dehydroepiandrosterone

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- pAktS473

phospho-AktS473

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

References

- 1.Maehama T, et al. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray IC, et al. Mutation and expression analysis of the putative prostate tumour-suppressor gene PTEN. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;78:1296–1300. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whang YE, et al. Inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN/MMAC1 in advanced human prostate cancer through loss of expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998;95:5246–5250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCall P, et al. Is PTEN loss associated with clinical outcome measures in human prostate cancer? Br. J. Cancer. 2008;99:1296–1301. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki H, et al. Interfocal heterogeneity of PTEN/MMAC1 gene alterations in multiple metastatic prostate cancer tissues. Cancer Res. 1998;58:204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlietstra RJ, et al. Frequent inactivation of PTEN in prostate cancer cell lines and xenografts. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2720–2723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshimoto M, et al. FISH analysis of 107 prostate cancers shows that PTEN genomic deletion is associated with poor clinical outcome. Br. J. Cancer. 2007;97:678–685. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMenamin ME, et al. Loss of PTEN expression in paraffin-embedded primary prostate cancer correlates with high Gleason score and advanced stage. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4291–4296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang S, et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford ED, et al. A controlled trial of leuprolide with and without flutamide in prostatic carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;321:419–424. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908173210702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenberger MA, et al. Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:1036–1042. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen MM, et al. Pten inactivation and the emergence of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6535–6538. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiao J, et al. Murine cell lines derived from Pten null prostate cancer show the critical role of PTEN in hormone refractory prostate cancer development. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6083–6091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen YQ, et al. Dietary fat-gene interactions in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:535–551. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norrish AE, et al. Prostate cancer risk and consumption of fish oils: a dietary biomarker-based case-control study. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;81:1238–1242. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terry P, et al. Fatty fish consumption and risk of prostate cancer. Lancet. 2001;357:1764–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang YJ, et al. Comparison of fatty acid profiles in the serum of patients with prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Clin. Biochem. 1999;32:405–409. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(99)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Augustsson K, et al. A prospective study of intake of fish and marine fatty acids and prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:64–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berquin IM, et al. Modulation of prostate cancer genetic risk by omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1866–1875. doi: 10.1172/JCI31494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barclay WW, et al. Culture of mouse prostatic epithelial cells from genetically engineered mice. Prostate. 2005;63:291–298. doi: 10.1002/pros.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barclay WW, et al. Characterization of adult prostatic progenitor/stem cells exhibiting self-renewal and multilineage differentiation. Stem Cells. 2008;26:600–610. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeifer A, et al. Delivery of the Cre recombinase by a self-deleting lentiviral vector: efficient gene targeting in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:11450–11455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201415498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng Z, et al. Yin Yang 1 regulates the transcriptional activity of androgen receptor. Oncogene. 2009;28:3746–3757. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson JF, et al. Plasma testosterone levels in C57BL/6J male mice: effects of age and disease. Acta. Endocrinol. (Copenh) 1975;80:744–752. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0800744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berquin IM, et al. Multi-targeted therapy of cancer by omega-3 fatty acids. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:363–377. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McEntee MF, et al. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids enhance hormone ablation therapy in androgen-dependent prostate cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;173:229–241. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ammirante M, et al. B-cell-derived lymphotoxin promotes castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2010;464:302–305. doi: 10.1038/nature08782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Vere White R, et al. Human androgen receptor expression in prostate cancer following androgen ablation. Eur. Urol. 1997;31:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000474409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregory CW, et al. A mechanism for androgen receptor-mediated prostate cancer recurrence after androgen deprivation therapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4315–4319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown RS, et al. Amplification of the androgen receptor gene in bone metastases from hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J. Pathol. 2002;198:237–244. doi: 10.1002/path.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visakorpi T, et al. In vivo amplification of the androgen receptor gene and progression of human prostate cancer. Nat. Genet. 1995;9:401–406. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koivisto P, et al. Androgen receptor gene amplification: a possible molecular mechanism for androgen deprivation therapy failure in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:314–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallen MJ, et al. Androgen receptor gene mutations in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J. Pathol. 1999;189:559–563. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199912)189:4<559::AID-PATH471>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linja MJ, et al. Amplification and overexpression of androgen receptor gene in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3550–3555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung BH, et al. Effects of docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid on androgen-mediated cell growth and gene expression in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1201–1206. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.8.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulholland DJ, et al. Cell autonomous role of PTEN in regulating castration-resistant prostate cancer growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss LA, et al. Ratio of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids and bone mineral density in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;81:934–938. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.4.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.