Abstract

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) with oral solubilized formula in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients, patients with probable or definite ALS were randomized to receive oral solubilized UDCA (3.5 g/140 mL/day) or placebo for 3 months after a run-in period of 1 month and switched to receive the other treatment for 3 months after a wash-out period of 1 month. The primary outcome was the rate of progression, assessed by the Appel ALS rating scale (AALSRS), and the secondary outcomes were the revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-R) and forced vital capacity (FVC). Fifty-three patients completed either the first or second period of study with only 16 of 63 enrolled patients given both treatments sequentially. The slope of AALSRS was 1.17 points/month lower while the patients were treated with UDCA than with placebo (95% CI for difference 0.08-2.26, P = 0.037), whereas the slopes of ALSFRS-R and FVC did not show significant differences between treatments. Gastrointestinal adverse events were more common with UDCA (P < 0.05). Oral solubilized UDCA seems to be tolerable in ALS patients, but we could not make firm conclusion regarding its efficacy, particularly due to the high attrition rate in this cross-over trial.

Keywords: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Ursodeoxycholic Acid, Cross-Over Trial

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disease that primarily affects upper and lower motor neurons, resulting in death three to five years after symptom onset in the majority of patients (1). The pathomechanism of ALS is largely unknown, but research efforts have been focused on several hypothetical models such as glutamate excitotoxicity, oxidative damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation and apoptosis (2). Numerous clinical trials have been performed, but unfortunately all failed to demonstrate any beneficial effects on the disease progression or survival, with the exception of riluzole.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (3α, 7β-dihydroxy-5β-cholanic acid, UDCA), a hydrophilic tertiary bile acid, is a major component of black bear bile that was used in traditional Chinese medicine (3). It is the current mainstay of treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis as the only drug approved by the US FDA, and has been increasingly used for the treatment of various cholestatic liver diseases such as primary sclerosing cholangitis and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (4, 5). Although the mechanisms of action is not completely understood, UDCA and its taurineconjugated derivative (TUDCA) have been shown to strongly inhibit apoptosis in different type of cells by either stabilizing the mitochondrial membrane, or modulating the expression of specific upstream targets of apoptosis (6-11). TUDCA improved the survival and function of nigral transplants in a rat model of Parkinson's disease (12), and the neuroprotective effect was also reported in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease (13), and rat models of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (14, 15).

ALS must be such a complex disease with numerous factors contributing to the degeneration of motor neurons, that an approach targeting a single molecule or process may not be effective (2). In this respect, UDCA may be a promising therapeutic candidate because of its multiple mechanisms of cytoprotective actions which may include antiapoptotic, immunomodulatory and antioxidant effects (6, 16, 17). Despite these therapeutic potentials, however, clinical application of UDCA has been limited to the hepatobiliary disorders exclusively. This is because of its unique pharmacokinetic properties which prevent the molecule from being delivered through systemic circulation, for example, to the central nervous system at potentially therapeutic concentrations (18). UDCA capsules or tablets, for instance, contain acid crystals with a very low solubility at pH < 7, and after administration of the pharmacological dose (10-15 mg/kg/day) UDCA is absorbed through passive non-ionic diffusion, which is largely limited by dilution mostly in the small intestine (18). Moreover, a large proportion of UDCA taken up from the portal blood is conjugated with glycine or taurine during its first hepatic passage, and actively secreted into the bile (18).

A new UDCA formula, oral solubilized UDCA (Yoo's solution; US patent 6251428, 7166299, 7303768 with PTC), was developed to broaden its therapeutic targets beyond the liver and biliary tracts eluding those pharmacokinetic limitations such as the enterohepatic circulation and high first-pass metabolism. The new formula contains intact UDCA molecules and soluble starch conversion product that enables UDCA to remain in solution. The product is highly soluble in water with a solubility of 80 mg/mL, and stable from pH 1 to 14 without producing precipitate (19, 20). It can deliver therapeutically effective amounts of solubilized intact UDCA to the systemic circulation with a Cmax of 20.4 µg/mL at a Tmax of 15 min in human blood after oral administration of single dose containing 500 mg of UDCA (20). Moreover, a preliminary study showed that UDCA can be effectively delivered to the central nervous system (cerebrospinal fluid, CSF) with oral administration of solubilized UDCA (described in the methods). The present study was performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral solubilized UDCA treatment in patients with ALS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, patients and treatment

The study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, cross-over, single center, phase III trial. Inclusion started in March 2005, and the final patient completed the study in July 2007. Patients with definite or probable sporadic ALS, according the revised El Escorial criteria, were enrolled (21). They had to be at or above 20 yr of age, and have disease duration of less than 60 months. The Appel ALS rating scale (AALSRS) total score had to be between 40 and 120 at baseline (22). Patients who had a forced vital capacity of less than 30%, those with signs of major psychiatric disorders and/or dementia, and acute cholecystitis or occlusion of bile duct, or patients who had another concomitant conditions likely to interfere with drug compliance and outcome assessment were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria were pregnancy and participation to other clinical trials.

Eligibility was assessed by two of the authors , and the eligible patients who gave informed consents were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment groups according to a randomization schedule prepared by Prime Pharm Tech, Corp (Suwon, Korea). There was no stratification of patients according to the onset region, age or respiratory function, since all the patients enrolled were supposed to receive both treatments (oral solubilized UDCA and placebo) sequentially in this cross-over trial. After a run-in period of 1 month, one group received oral solubilized UDCA (UDCA 3.5 g/140 mL q.d., Prime Pharm Tech, Corp.) for 3 months, while the other group received placebo (identically-appearing, equal amount of solution q.d., Prime Pharm Tech, Corp.). Subsequently, the two groups switched to receive the other treatment for another 3 months during the second period of study. To eliminate a possible carry-over effect of oral solubilized UDCA, a wash-out period of 1 month was set at the beginning of the second period. To ensure blinding, placebo was made to be identical to oral solubilized UDCA in viscosity as well as appearance (color, packaging and labeling), and to be similar in bitter taste (by adding quinine hydrochloride in placebo).

A preliminary study was performed to test if UDCA can be effectively delivered to the central nervous system with oral administration of solubilized UDCA. Seven patients were all treated with oral solubilized UDCA with informed consents. After the first 3 months of treatment, pure UDCA was detected with concentrations ranging from 0.75 to 1.72 µM/L in CSF of these patients (JASCO Bile Acid Analysis System, Japan Spectroscopic Co., Ltd., Tokyo; data not shown).

Efficacy and safety evaluation

Patients were scheduled to visit for outcome assessment at month 1, 4, 5, and 8 throughout the 8-month study period. The primary outcome measure was the rate of progression, measured by the AALSRS, i.e., the slope of AALSRS (22, 23). Secondary outcome measures were the deterioration rates, assessed by the revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-R) and forced vital capacity (FVC, % of predicted value) (24, 25). To preserve blinding, efficacy measures were assessed by two independent investigators, who were not otherwise involved in the care of patients throughout the trial. Treatment adherence was checked monthly by a pharmacist, and noncompliant patients who took the study medications less than 80% of the given were considered to have violated the treatment protocol. Standard laboratory tests including blood counts, chemistry, renal and liver function, and electrocardiogram were performed at baseline and at the posttreatment discontinuation visit. Safety was evaluated as the incidence and severity of adverse events, and their relationship to treatment which were based on the results of laboratory tests, patients' reports and the investigator's judgements.

Statistical analysis

We hypothesized that oral solubilized UDCA therapy slows the deterioration of function in patients with ALS, as assessed by comparing the slopes of AALSRS while the patients were treated with oral solubilized UDCA to those whilst on placebo. It was calculated that 48 patients, i.e., 24 patients in each treatment group, would have to be included in order to detect a difference of 10% in the mean slope of AALSRS between the two treatments with a power of 80% and an alpha risk of 5%. The sample size calculation was based on data from a previous study using the AALSRS to measure the functional deterioration in patients with ALS (26).

Efficacy was analyzed using the data from the patients who completed the study without any protocol violation. No imputation process was performed for missing data. Data for efficacy analysis were divided into two sets of per-protocol (PP). The first PP (PP) dataset were defined as the data from the patients who completed either the first or second period of study, while the second PP (PP') dataset consisted of the data only from the patients who completed both the first and second periods of study. Data of the patients whose slopes of AALSRS were steep (defined as greater than 24 points during a 3-month period) were excluded from efficacy analysis because inclusion of those atypical patients who progressed very rapidly could seriously distort the result (26). Using the SAS General linear model (GLM), analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed with the slope as the dependent variable, treatment as factor, and the period and sequence as covariates. Safety analysis was performed in all randomized patients who had taken at least one study drug or placebo. Baseline characteristics of patients including demographic and clinical variables were compared between patients treated with oral solubilized UDCA and those with placebo. Incidence of adverse events was compared between the two treatments using the chi-square. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, and the results are reported with two-sided P values.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and Korean Good Clinical Practice (KGCP) guidelines. The study protocol was submitted to and approved by the Korean Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) (16409), and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital (H-0301-099-007). All patients gave written informed consent before trial entry. Overall trial-related activities and documents were overseen by an Independent Auditory Board (C&R Research, Seoul, Korea).

RESULTS

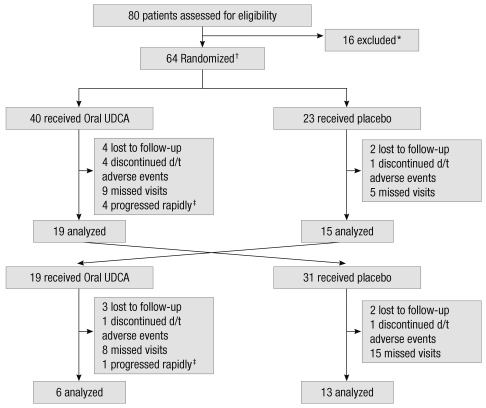

The trial profile is illustrated in Fig. 1. A total of 80 patients were assessed for eligibility, and 64 patients were enrolled in this study (one in error). Reasons for exclusion were the AALSRS total score greater than 120 or disease duration longer than 60 months (n = 10), severe depression (n = 3), and clinically possible ALS (n = 2) and cognitive impairment (n = 1). Forty of 63 patients were assigned to receive oral solubilized UDCA in the first period of study, and the other 23 patients to receive placebo. During the first period, 19 of 40 (47.5%) patients treated with oral solubilized UDCA and 15 of 23 (65.2%) patients treated with placebo completed the study. All patients who completed the first period switched to receive the other treatment in the second period. The patients who dropped out during the first period of study were also scheduled to enter the second period of study after originally planned three months had passed with the other treatment given for the second period. Thus, 31 of 40 (77.5%) randomized to oral solubilized UDCA and 19 of 23 (82.6%) randomized to placebo for the first period switched to receive placebo and oral solubilized UDCA, respectively, for the second period of study. During the second period, 6 of 19 (31.6%) treated with oral solubilized UDCA and 13 of 31 (41.9%) treated with placebo completed the study. Drop-out rates were higher during the second period (62%) than the first (46%), and also higher whilst on oral solubilized UDCA (57.6%) than placebo (48.1%). Only 16 out of 63 enrolled patients completed the entire cross-over trial of 8-month, receving both treatments. Missed visits was the most common reason for drop-out (62%), followed by lost to follow-up (18%), discontinuation due to adverse events (12%) and a rapid progression (8%).

Fig. 1.

Trial profile. *all not meeting inclusion criteria; †one ineligible patient was randomized in error; ‡excluded from analysis due to a rapid rate of progression, i.e., the Appel ALS total score change > 8 points/month.

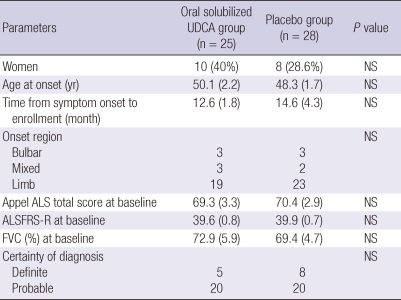

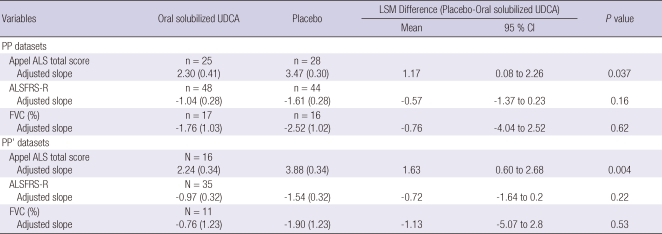

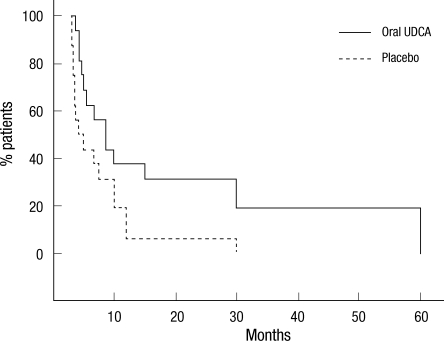

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients treated with either oral solubilized UDCA or placebo are outlined in Table 1. The patients treated with oral solubilized UDCA and placebo were comparable to each other at baseline with respect to sex, age at onset, disease duration from symptom onset to diagnosis, onset region, severity, and level of diagnostic certainty. We constructed the dataset for efficacy analysis separately for each outcome, because the AALSRS and FVC measures were missing more frequently than the ALSFRS-R. The results of efficacy analysis for each outcome were summarized in Table 2. As for the PP datasets, the slope of AALSRS was 1.17 points/month lower while the patients were treated with oral solubilized UDCA than with placebo (2.3 vs 3.47 points/month, 95% CI for difference 0.08-2.26, P = 0.037). However, the slope of neither ALSFRS-R nor FVC (%) did not show any significant differences between treatments. Efficacy analysis from the PP' datasets revealed the same results as from the PP datasets. The slope of AALSRS was 1.63 points/month slower while the patients were treated with oral solubilized UDCA than with placebo (2.24 vs 3.88 points/month, 95% CI for difference 0.60-2.68, P = 0.004), whereas the ALSFRS-R and FVC (%) deteriorated without significant differences between the two treatments. To infer the clinical meaning from the slope data, Kaplan-Meier estimation was performed using a 20-points progression in the AALSRS total score as the end point which was reported to represent a clinically meaningful lifestyle change. However, because of the short study period of this trial, the time to reach this endpoint had to be estimated in all patients, and was calculated by assuming that the slope of AALSRS would be linear from the start of treatment through the endpoint. As for the PP' datasets, the time to a 20-points progression in the AALSRS total score was estimated to be delayed by 14.9 months in oral solubilized UDCA-treated group compared to placebo-treated group (22.5 vs 7.6 months, 95% CI for difference 2.97-26.8 months, P = 0.018) (Fig. 2). Additionally, we compared clinical features between 60 patients who dropped out and 53 patients who completed at least one part of the study. At baseline, sex, age at onset, age at enrollment, disease duration from symptom onset to diagnosis, onset region, severity, and level of diagnostic certainty were not significantly different between two groups (all, P > 0.05). Safety data from each period of study were pooled to provide a whole picture of the adverse event profile. The population for safety analysis consisted of 74 patients who took oral solubilized UDCA, and 70 patients who took placebo (Table 3). Not included for safety analysis were the patien ts who did not take the study drug or placebo at all, 6 patients assigned to oral solubilized UDCA and 10 patients to placebo.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

Data above are from the patients who completed either the first or second period of study. Baseline refers to the last measurement before the start of treatment during each period of study. ALSFRS-R and FVC (%) at baseline are from the first PP dataset on the corresponding outcome variable. Values are No. (%) or mean (standard error). UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALSFRS-R, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale-revised; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Table 2.

Results of efficacy analysis

Least square means (LSM) of slope and p-values were obtained from the analysis of covariance model with change from baseline (slope) as the dependent variable, treatment (Oral solubilized UDCA vs placebo) as factor, and the period and sequence as covariates. Values in paresthesis are standard errors of LSM. Efficacy was analyzed separately for each outcome without imputation for missing data, and definitions of the PP and PP' datasets were as followings: PP datasets, the data from the patients (n) who completed either the first or second period of study; PP' datasets, the data from the patients (N) who completed both the first and second periods of study.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves, using a change of 20 points on the Appel ALS total score as the end point. Time to 20 points progression was estimated by assuming a linearity of the change in the Appel ALS total score. In two patients whose slope was not above zero (zero in one, and -0.33 point/month in the other, both treated with oral solubilized UDCA), the time to 20 point progression was estimated to be 60 months, i.e., 1 point/3 month.

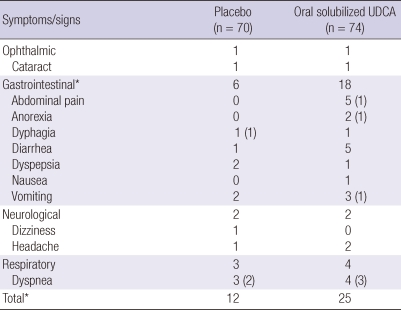

Table 3.

Incidence of adverse events

Data are numbers of events (number of serious adverse events). *P < 0.05, chi-square test.

A total of 25 occasions of adverse events were reported in 17 patients (23.0%) treated with oral solubilized UDCA, and 12 occasions in 10 patients (14.3%) treated with placebo. Except for the expected complications of ALS such as dyspnea and dysphagia, adverse events that could be possibly attributed to the study drug or placebo were reported in 12 patients (16.2%, 16 occasions) treated with oral solubilized UDCA, and in 6 patients (8.6%, 7 occasions) treated with placebo. Gastrointestinal adverse events were significantly more common in patients treated with oral solubilized UDCA (P < 0.05), but serious events were reported in only one patient who discontinued the drug due to abdominal pain, anorexia and vomiting. None of the 80 patients who were randomized died during the 8-month period of study, with tracheostomy performed in 2 patients.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest that oral solubilized UDCA therapy may have a beneficial effect on the rate of functional decline in patients with ALS. As for the slope of AALSRS, the difference between oral solubilized UDCA and placebo was 1.17 and 1.63 points per month on the average for the PP and PP' datasets, respectively, which correspond to 34% and 42% relative slowing of the rate of deterioration in this scale. Although estimated, the time to a 20-points progression in the AALSRS also showed that oral solubilized UDCA treatment could delay this endpoint by more than 1 yr compared to placebo. Although it was not statistically significant, the efficacy data in the other outcomes also showed a trend favoring oral solubilized UDCA. Although gastrointestinal adverse events developed more frequently in patients treated with oral solubilized UDCA, these were mostly tolerable and oral high dose solubilized UDCA was well tolerated in vast majority of patients. Taken together, this study suggests a therapeutic potential and acceptable safety profile of oral solubilized UDCA in ALS patients.

However, no firm conclusion cannot be made on the efficacy of oral solubilized UDCA because of several critical problems and limitations of this study which should be acknowledged herein. First of all, the major problem was the large drop-out rate in this trial. In fact, only about a fourth of the initially randomized patients completed both parts of the study with missed visits, followed by lost to follow-up, being the most common drop-out reason. The patients, who had already severe disease at enrollment or became progressively more disabled during the study, tended to refuse to visit the clinic for outcome measures. These patients were also hard to keep contact with for consistent follow-up. Thus, it is likely that the broad inclusion criteria regarding disease severity, and the lack of adherence to visit schedule for outcome measures account for the large attrition rate. The second problem of this study is the way data were analyzed, i.e., 'completers-only' analysis. Since only the patients who completed the planned treatment course were included for efficacy analysis, this does not conform to the intention-to-principle. We cannot rule out faster declines for patients after their dropout, and excluded cases can cause a bias, although baseline clinical features of patients completing the study and patients dropping-out the study were not different. However, we could not apply the intention-to-treat principle, since the attrition rate was too large for us to perform any valid imputation procedure for missing data. Other limitations of this study are the short treatment period and limited number of datapoints to assess the rates of functional deterioration. Treatment period of 3 months might not be sufficient duration to capture a small effect. In addition, the outcome measures may not be reproducible to give accurate statistics with only two datapoints. Finally, it also should be pointed out that all the patients who were excluded due to their rapid progression rates (> 8 points/month) were those taking oral solubilized UDCA.

An ethical concern about treatment with placebo was the main reason we adopted a cross-over design instead of conventional two parallel arm study (27). It was also expected that the crossover design would be more efficient in detecting the same effect with a smaller sample size, since within-patient variability may be smaller than between-patient variability when the deterioration rates of functional scales are used as endpoints (28, 29). However, there might be disadvantages to the cross-over trial as well, and some of these indeed caused difficulties for analysis and interpretation of our study. First, there may be a bias which is related to the unequal randomization for the first treatment period. It is likely that merely the sequence of treatment may explain the difference between treatments, although we adjusted the effects of sequence and period using ANCOVA to evaluate the effect of treatment itself. The other problem is a treatmentperiod interaction, so-called a carry-over effect. The wash-out period of 1 month may be insufficient to completely eliminate the effect of treatment given before. However, we could exclude the inflation of alpha-error resulting from the carry-over effect, because any persistence of the drug effect would have reduced the magnitude of difference during the second treatment period.

It is worth emphasizing that UDCA can be effectively delivered to the central nervous system (CSF) with oral administration of solubilized UDCA in our study. A recent pilot study by Parry et al. also showed that UDCA was well absorbed after oral administration and crossed the blood-brain barrier in a dose-dependent manner in ALS patients (30). Eighteen patients were received UDCA in tablet formula at doses of 15, 30, and 50 mg/kg of body weight per day and the concentration of UDCA in CSF ranged 43.1 to 281.7 nM/L after 4 weeks of treatment. These results suggest that oral UDCA is well delivered to CSF of ALS patients and the therapeutic effects deserve to be expected although it remains to be elucidated which formula or dose of UDCA is more tolerated, absorbed, delivered and effective in ALS patients.

Although the mechanisms of cytoprotection of UDCA remain to be elusive, it does not seem to be limited to hepatic cells. UDCA modulates the apoptotic threshold in both hepatic and non-hepatic cells through the downregulation of p53 pathway (10, 11). Recently, a study using oral solubilized UDCA demonstrated that UDCA treatment can suppress cisplatin-induced p53 accumulation and apoptosis in mouse sensory neurons (19). It was also reported that this highly soluble and acid stable UDCA formula can scavenge the reactive oxygen species and prevent apoptosis in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis (20). In line with these previous reports, we also found that the new UDCA formula improved the motor performance and survival of G93A SOD1 mutant transgenic mice (in preparation). Therefore, the therapeutic effect of UDCA may be ascribed to the successful delivery of UDCA to the central nervous system and its multiple cytoprotective actions.

Oral solubilized UDCA treatment seems to be tolerable in ALS patients, but regarding the efficacy we could not make any conclusions due to several problems and limitations of this pilot study as discussed above. Still, the effect of UDCA deserves to be expected in ALS, due to its multiple neuroprotective mechanism. As we know, a phase II trial for the efficacy and tolerability of tauroursodeoxycholic acid, taurine conjugate of UDCA in ALS patients is also ongoing (NCT00877604) by Italian researchers. Further large scale study with minimal attrition rate is warranted to confirm the efficacy and safety of oral solubilized UDCA for patients with ALS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank to Seo Hong Yoo and Dong Jin Yoo for the detection of oral solubilized UDCA in human CSF.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant of the Seoul National University Hospital (20054179).

References

- 1.Mitchell JD, Borasio GD. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2007;369:2031–2041. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60944-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boillée S, Vande Velde C, Cleveland DW. ALS: a disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors. Neuron. 2006;52:39–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagey LR, Crombie DL, Espinosa E, Carey MC, Igimi H, Hofmann AF. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the Ursidae: biliary bile acids of bears, pandas, and related carnivores. J Lipid Res. 1993;34:1911–1917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leuschner U, Fischer H, Kurtz W, Güldütuna S, Hübner K, Hellstern A, Gatzen M, Leuschner M. Ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cirrhosis: results of a controlled double-blind trial. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1268–1274. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91698-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Ursodeoxycholic acid 'mechanisms of action and clinical use in hepatobiliary disorders'. J Hepatol. 2001;35:134–146. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodrigues CM, Steer CJ. The therapeutic effects of ursodeoxycholic acid as an anti-apoptotic agent. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:1243–1253. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.7.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues CM, Stieers CL, Keene CD, Ma X, Kren BT, Low WC, Steer CJ. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid partially prevents apoptosis induced by 3-nitropropionic acid: evidence for a mitochondrial pathway independent of the permeability transition. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2368–2379. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solá S, Castro RE, Laires PA, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid prevents amyloid-beta peptide-induced neuronal death via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent signaling pathway. Mol Med. 2003;9:226–234. doi: 10.2119/2003-00042.rodrigues. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solá S, Castro RE, Kren BT, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. Modulation of nuclear steroid receptors by ursodeoxycholic acid inhibits TGF-beta1-induced E2F-1/p53-mediated apoptosis of rat hepatocytes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8429–8438. doi: 10.1021/bi049781x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramalho RM, Borralho PM, Castro RE, Solá S, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid modulates p53-mediated apoptosis in Alzheimer's disease mutant neuroblastoma cells. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1610–1618. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amaral JD, Castro RE, Solá S, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. p53 is a key molecular target of ursodeoxycholic acid in regulating apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34250–34259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duan WM, Rodrigues CM, Zhao LR, Steer CJ, Low WC. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid improves the survival and function of nigral transplants in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:195–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keene CD, Rodrigues CM, Eich T, Chhabra MS, Steer CJ, Low WC. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid, a bile acid, is neuroprotective in a transgenic animal model of Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10671–10676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162362299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodrigues CM, Spellman SR, Solá S, Grande AW, Linehan-Stieers C, Low WC, Steer CJ. Neuroprotection by a bile acid in an acute stroke model in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:463–471. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigues CM, Sola S, Nan Z, Castro RE, Ribeiro PS, Low WC, Steer CJ. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid reduces apoptosis and protects against neurological injury after acute hemorrhagic stroke in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6087–6092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031632100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellentani S. Immunomodulating and anti-apoptotic action of ursodeoxycholic acid: where are we and where should we go? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:137–140. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200502000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serviddio G, Pereda J, Pallardó FV, Carretero J, Borras C, Cutrin J, Vendemiale G, Poli G, Viña J, Sastre J. Ursodeoxycholic acid protects against secondary biliary cirrhosis in rats by preventing mitochondrial oxidative stress. Hepatology. 2004;39:711–720. doi: 10.1002/hep.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofmann AF. Pharmacology of ursodeoxycholic acid, an enterohepatic drug. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1994;204:1–15. doi: 10.3109/00365529409103618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park IH, Kim MK, Kim SU. Ursodeoxycholic acid prevents apoptosis of mouse sensory neurons induced by cisplatin by reducing P53 accumulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thao TD, Ryu HC, Yoo SH, Rhee DK. Antibacterial and anti-atrophic effects of a highly soluble, acid stable UDCA formula in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:2135–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293–299. doi: 10.1080/146608200300079536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appel V, Stewart SS, Smith G, Appel SH. A rating scale for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: description and preliminary experience. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:328–333. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haverkamp LJ, Appel V, Appel SH. Natural history of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a database population. Validation of a scoring system and a model for survival prediction. Brain. 1995;118:707–719. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, Fuller C, Hilt D, Thurmond B, Nakanishi A BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III) The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. J Neurol Sci. 1999;169:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Czaplinski A, Yen AA, Appel SH. Forced vital capacity (FVC) as an indicator of survival and disease progression in an ALS clinic population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:390–392. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lange DJ, Murphy PL, Diamond B, Appel V, Lai EC, Younger DS, Appel SH. Selegiline is ineffective in a collaborative double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:93–96. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grizzle JE. The two-period change-over design an its use in clinical trials. Biometrics. 1965;21:467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller RG, Moore DH, 2nd, Gelinas DF, Dronsky V, Mendoza M, Barohn RJ, Bryan W, Ravits J, Yuen E, Neville H, Ringel S, Bromberg M, Petajan J, Amato AA, Jackson C, Johnson W, Mandler R, Bosch P, Smith B, Graves M, Ross M, Sorenson EJ, Kelkar P, Parry G, Olney R Western ALS Study Group. Phase III randomized trial of gabapentin in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2001;56:843–848. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traynor BJ, Zhang H, Shefner JM, Schoenfeld D, Cudkowicz ME NEALS Consortium. Functional outcome measures as clinical trial endpoints in ALS. Neurology. 2004;63:1933–1935. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144345.49510.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parry GJ, Rodrigues CM, Aranha MM, Hilbert SJ, Davey C, Kelkar P, Low WC, Steer CJ. Safety, tolerability, and cerebrospinal fluid penetration of ursodeoxycholic acid in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:17–21. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181c47569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]