Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SS) is a connective tissue disease and cardiac involvement is common. Primary cardiac involvement such as conduction system disturbances and arrhythmias can also occur. However, reports of sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) are rare. We report a case of catheter ablation of sustained ventricular tachycardia in a patient with systemic sclerosis using a conventional mapping system. A 64-yr-old woman with a 10-yr history of SS was referred for management of her ventricular tachycardia. There was no structural abnormality in cardiac chambers. However, electrophysiologic study revealed electrical substrate of ventricular tachycardia which could be ablated with pacemapping and substrate mapping. This case demonstrated successful conventional mapping and catheter ablation in a hemodynamically unstable patient with SS.

Keywords: Scleroderma Systemic, Tachycardia Ventricular, Catheter Ablation

INTRODUCTION

Rhythm disturbances have been described in immunological and connective diseases (1). Systemic sclerosis (SS) is a fibrotic condition characterized by immunological abnormalities, vascular injury and increased accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins (2). The heart is one of the major organs involved in SS and cardiac involvement has been a common finding at postmortem examination (3). Conduction disturbances as well as supraventricular tachycardia or ventricular extrasystoles commonly occur during Holter monitoring (4). Nonetheless, reports of sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) are rare. The mechanisms underlying ventricular arrhythmias in systemic sclerosis have not been well studied. In this report, we describe a case of successful treatment of hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia in a patient with SS by catheter ablation with substrate mapping.

CASE DESCRIPTION

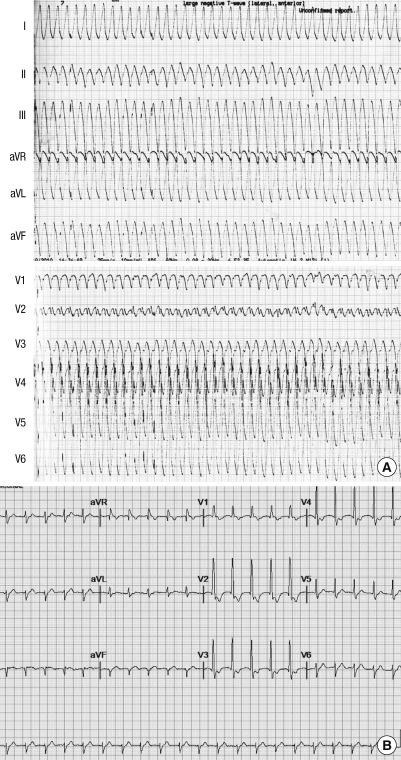

A 64-yr-old woman with a 10-yr history of SS was referred for management of her ventricular tachycardia. The manifestations of SS included pulmonary interstitial fibrosis and mild pulmonary hypertension managed by prednisolone and azathioprine. She was admitted to the emergency department on July 17, 2009 and the initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed monomorphic wide QRS tachycardia which was well tolerated despite a rate of 243 beats per minute (Fig. 1A). Wide QRS tachycardia observed in the ECG showed a left bundle branch block, left axis deviation and atrioventricular dissociation. A profile of routine chemistry including myocardiac markers did not reveal any specific abnormalities. Antinuclear antibody screening and specific tests for antitopoisomerase III (anti-Scl-70) were positive and ESR was 94 mm/hr. Chest X-ray showed basal-predominant reticular abnormality. Sinus rhythm with normal QT interval (QTc: 453 ms) was restored with electrical cardioversion (Fig. 1B). Echocardiography showed preserving LV ejection fraction and normal cardiac chamber size without structural abnormality of both ventricle. Mild pulmonary hypertension was monitored as 35 mmHg pulmonary artery pressure.

Fig. 1.

Initial ECG at emergency room. (A) Twelve lead ECG on admission revealed sustained monomorphic VT with LBBB configulation and left axis deviation. (B) Sinus rhythm with incomplete RBBB and normal QT interval (QTc:453 ms) was restored by electrical cardioversion.

On the 2nd day after admission, wide QRS tachycardia with the same morphology recurred. The tachycardia was persistent and the patient's blood pressure dropped below 80 mmHg. Electrical cardioversion was urgently performed and sinus rhythm was recovered.

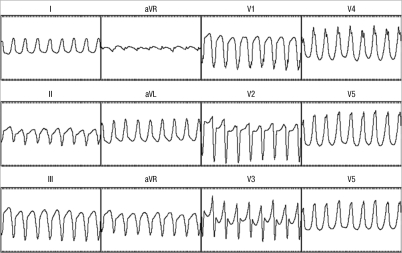

A coronary angiogram and electrophysiological study with radiofrequency catheter ablation were performed on the 3rd hospital day. There was no significant stenosis in coronary artery. During the electrophysiological test, sustained ventricular tachycardia of the same morphology with clinically documented tachycardia was reproducibly induced by two ventricular extra stimuli (Fig. 2). The induced VTs were hemodynamically unstable and do not permit activation mapping or entrainment during prolonged periods of tachycardia. Therefore, we performed a substrate mapping during sinus rhythm and pace mapping instead of activation mapping or entrainment.

Fig. 2.

Induced VT during the electrophysiologic study. This VT was morphologically identical with clinically documented VT (LBBB morphology and left axis deviation).

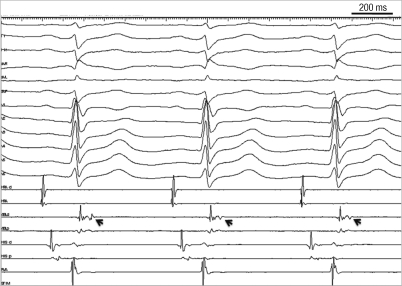

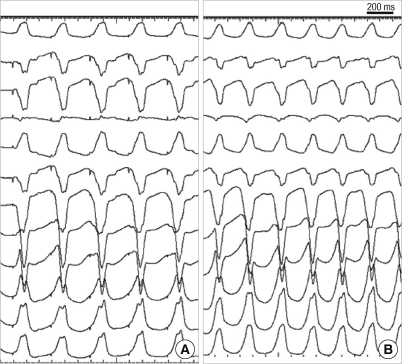

During substrate mapping, delayed and isolated potential was found at the posterior base of the right ventricle (Fig. 3). Pacemapping in the area showed satisfactory 12-lead QRS matching with induced ventricular tachycardia (Fig. 4). Ablation was started at the vicinity of the area, where the typical delayed and isolated potentials were found. Twelve radiofrequency currents were delivered at these sites in a temperature-controlled mode at 60℃ with power limited to 50 W.

Fig. 3.

During substrate mapping in sinus rhythm, delayed and late potentials (black arrow) were identified at the mapping catheter.

Fig. 4.

Pacemapping at the area of late potential showed good matching with induced VT. (A) 12 lead ECG during pacemapping (B) 12 lead ECG duing ventricular tachycardia.

After the final RF application, ventricular tachycardia was not induced either by the programmed extrastimuli or isoproterenol infusion up to 10 µg/mim. After the procedure, there was no further inter/intraventricular conduction delay on ECG. Telemetry monitoring revealed that the ventricular tachycardia did not recur and normal sinus rhythm was maintained.

The patient was discharged and beta blockers, prednisolone and azathioprine were maintained. Follow-up observations are ongoing, and neither VT nor any cardiac symptoms have recurred.

DISCUSSION

This report describes a successful catheter ablation of a hemodynamically unstable VT arising from the posterior base of right ventricle in a patient with SS. Cardiovascular involvement is common in SS. Tachyarrhythmia appears as a frequent clinical manifestation of SS-associated cardiovascular damage and a possible cause of sudden death (5). In one study, premature ventricular contraction was the most common arrhythmia and noted in 67% including PVCs in pairs in 20%, VT in 7%. The incidence of sustained VT seems relatively low (6). However, if sustained VT occurs in these patients, it could be fatal. Our case was thought rare and interesting with a high possibility of sudden death due to sustained VT associated with SS.

The mechanisms of tachyarrhythmia in SS are probably multiple. Among them, a re-entry mechanism due to diffuse myocardial fibrosis would provide sustained monomorphic VT (7, 8). Successful treatment with surgical cryoablation and catheter ablation have been reported. The implantable cardioverter defibrillator has been used in survivors of cardiac arrest (8, 9). In our case, unlike VTs in previous reports, the VT was associated with hemodynamic instability. Therefore, we could not use activation mapping or entrainment mapping during prolonged periods of tachycardia due to the hemodynamically unstable nature. In scar based reentrant VT, slow conduction takes place on the border of the scar tissue; therefore, abnormal and low amplitude electrograms have been recorded during sinus rhythm at these sites. As low-amplitude electrograms are recorded all along the scarred endocardial surface, they have low specificity for VT substrate identification. The exit site of the VT should be identified and targeted with ablation using pace-mapping at the border of the scar.

Furthermore, a recent study (10) suggested that the contribution of scar to the electrophysiological abnormalities targeted for ablation of unstable VT differs between ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) and nonischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM). Mean total low voltage area in patients with ICM was larger than in NICM. Within the total low voltage area, late potentials were observed more frequently in ICM than in NICM in endocardium and epicardium. Therefore, an approach incorporating late potential ablation and pace-mapping can be considered and electroanatomical mapping can be an alternative in patients with NICM.

This case demonstrated successful conventional mapping and catheter ablation in a patient with SS, despite a hemodynamically unstable state. In the future, we suggest the need for her to insert implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

References

- 1.Lazzerini PE, Capecchi PL, Guideri F, Acampa M, Selvi E, Bisogno S, Galeazzi M, Laghi-Pasini F. Autoantibody-mediated cardiac arrhythmias: mechanisms and clinical implications. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0686-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto T. Scleroderma: pathophysiology. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:14–24. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulkley BH, Riodolfi RL, Salyer WR, Hutchins GM. Myocardial lesions of progressive systemic sclerosis. A cause of cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 1976;53:483–490. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.53.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts NK, Cabeen WR, Jr, Moss J, Clements PJ, Furst DE. The prevalence of conduction defects and cardiac arrhythmias in progressive systemic sclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:38–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-94-1-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazzerini PE, Capecchi PL, Guideri F, Acampa M, Galeazzi M, Laghi-Pasini F. Connective tissue diseases and cardiac rhythm disorders: an overview. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kostis JB, Seibold JR, Turkeich D, Masi AT, Grau RG, Medsger TA, Jr, Steen VD, Clements PJ, Szydlo L, D'Angelo WA. Prognostic importance of cardiac arrhythmias in systemic sclerosis. Am J Med. 1988;84:1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rankin AC, Osswald S, McGovern BA, Ruskin JN, Garan H. Mechanism of sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in systemic sclerosis. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:633–636. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00935-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacroix D, Brigadeau F, Marquié C, Klug D. Electroanatomic mapping and ablation of ventricular tachycardia associated with systemic sclerosis. Europace. 2004;6:336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rankin AC. Arrhythmias in systemic sclerosis and related disorders. Card Electrophysiol Rev. 2002;6:152–154. doi: 10.1023/a:1017924213904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakahara S, Tung R, Ramirez RJ, Michowitz Y, Vaseghi M, Buch E, Gima J, Wiener I, Mahajan A, Boyle NG, Shivkumar K. Characterization of the arrhythmogenic substrate in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy implications for catheter ablation of hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2355–2365. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]