Abstract

Background: The Patient Health Questionnaire depression module (PHQ-9) is a brief (10 items) screening and monitoring measure designed for use in primary care settings that operationalizes most of the DSM-IV and ICD-9 diagnostic criteria for major depression. In the United States, the PHQ-9 has become the recommended depression measure in primary care settings. However, there are no published reports of its use in developing countries and no reports of the feasibility of using the Spanish version of the PHQ-9 to screen for depression.

Method: During a medical brigade in October 2001, we tested the feasibility of using the Spanish PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in primary care clinics. A team of U.S. and Honduran physicians and medical students assessed 199 mothers of children under 10 years of age as part of a depression prevalence study in 5 rural sites.

Results: The PHQ-9 proved easy to administer to this population of poor, rural, young, and mostly illiterate Honduran women who had never participated in research before. Rater training required about 30 minutes of instruction for this group of physicians and medical students, plus occasional questions on the first day of use. Duration of administration of the PHQ-9 by interview ranged from 3 to 15 minutes. No items required major modification for cultural differences. The PHQ-9 identified a rate of 15% for major depression in this sample, and the PHQ-9 results showed a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 100% compared with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV mood disorders module.

Conclusion: Like the English PHQ-9, the Spanish PHQ-9 is an efficient and reliable screening measure for major depression in primary care. It is useful as a research measure for estimating the prevalence of major depression and as an aid to the primary care clinician in rural Honduras.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)1 was developed to provide a brief self-report diagnostic instrument for the diagnosis of mental disorders in primary care. It differs from other common case-finding instruments for mental disorders in that it is structured to operationalize the essential DSM-IV criteria for the most common mental disorders in primary care: depression, anxiety, substance abuse, eating disorders, and somatization disorders. The PHQ has been validated against the Diagnostic Interview Schedule in 2 large studies1,2 and has been adopted as the standard screening and monitoring measure in 1 large clinical trial3 and in several national initiatives on depression and primary care funded by the MacArthur Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

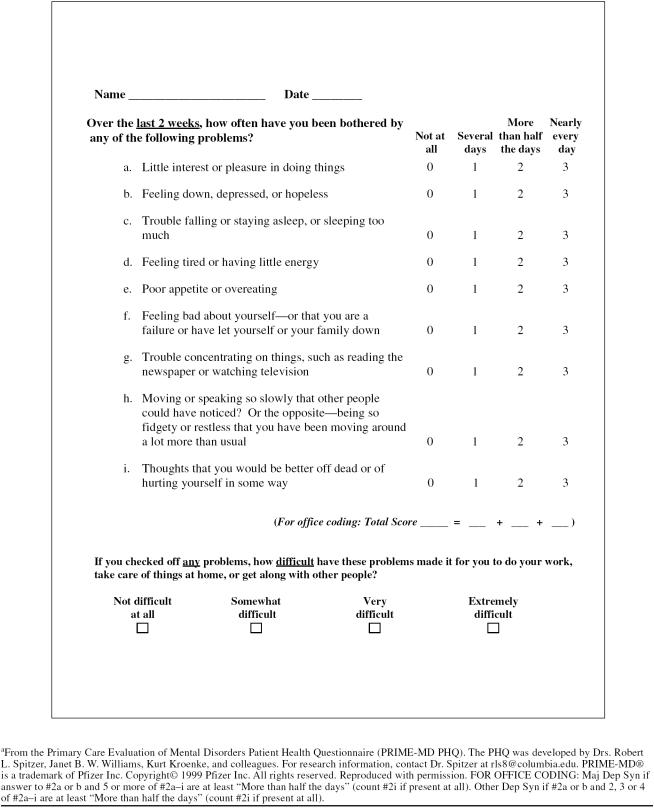

The PHQ-9 (Appendix 1) is the depression module of the PHQ. It refers to the previous 2-week interval and consists of 9 items of depression symptoms plus a question about functional impairment. It fits on 1 page. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 3, and scoring simply requires adding the numbers circled for a range of 0 to 27. An easy algorithm for the diagnosis of major depressive syndrome (5 items scored 2 or 3, one of which is a or b, and h counts if scored 1 or more) guides the interpretation of the pattern of responses.

Kroenke and colleagues4 recently published a validation study of the PHQ-9, testing it for criterion validity against independent structured diagnostic interviews and for construct validity against a standard measure of physical and mental functioning as well as against sick days and clinic visits. This study concludes that the PHQ-9 is a “reliable and valid measure of depression severity” and a “useful clinical and research tool.”(p613)

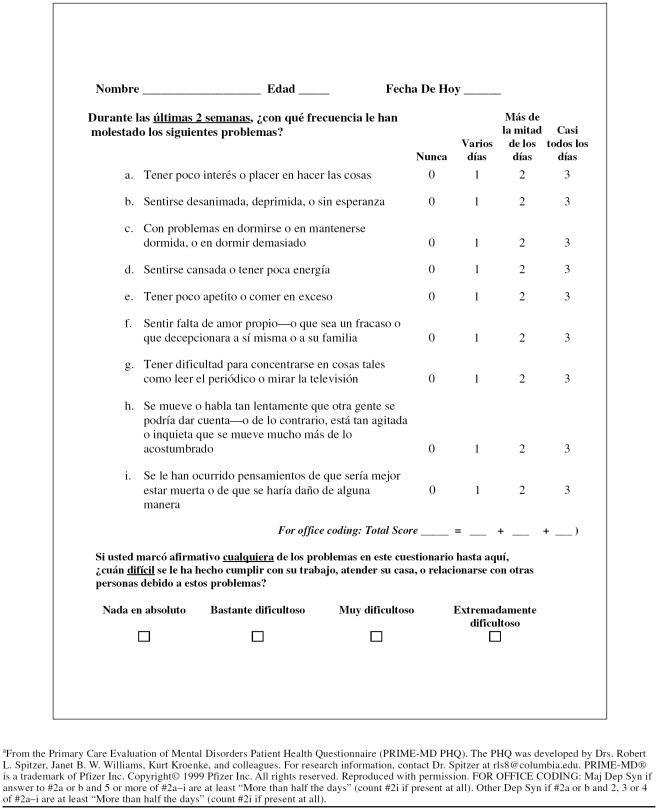

The PHQ-9 is one of a number of English-language depression questionnaires that have been validated in primary care settings.5 However, there have been few studies of the prevalence of depression in Spanish-speaking countries, and there are no published reports of depression in primary care or community samples in Central American countries. In our efforts to initiate research on mental disorders in Honduras, we began in the late 1990s with the use of the Spanish Beck Depression Inventory, a 21-item self-report measure that quantifies depression severity, but does not provide diagnostic specificity. So when the PHQ was developed and published in 1999, we became interested in studying the feasibility of using the Spanish version of the PHQ-9 to assess major depression for research and clinical purposes. The Spanish PHQ-9 (Appendix 2) is provided by the authors of the PHQ and is available for public use.

METHOD

We assessed the feasibility of using the Spanish PHQ-9 in 2 steps. In the context of the early phase of a prevalence study funded by Pfizer Inc and currently still in the process of data collection, a team of physicians and medical students administered the Spanish PHQ-9 as an interview with the help of Honduran student translators to 199 mothers of children under 10 years of age at 5 rural clinic sites near Santa Lucia, Intibuca, Honduras, and in surrounding neighborhoods during October 2001. For the administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) mood disorders module interviews, we selected roughly one third of the interviewed subjects who had low PHQ-9 scores (score < 10), one third with moderately severe depression (score of 10–15), and one third with severe depression (score > 15).

Feasibility measures of interest included training time, administration time, administration difficulties, item modifications required by cultural differences, scoring time, scoring problems, error rates, and sensitivity and specificity for major depression in relationship to the SCID mood disorders module.

RESULTS

The mean age of the sample (N = 199) was 32.2 years. The mean number of years of schooling for these mothers was 3.5. The mean number of children was 4.3.

Training time for physicians and medical students for these 2 projects consisted of about 30 minutes reviewing the purpose, format, items, scoring, and sample responses. For all raters this was sufficient to prepare them to complete the PHQ-9 forms with low error rates and only occasional questions.

Duration of administration of the PHQ-9 by interview format with the help of a student translator ranged from 3 to 15 minutes. Duration increased with severity of depression and amount of interference from the setting; duration decreased with practice and amount of rater's previous clinical experience with depression.

No major administration difficulties were reported. No subjects were unable to complete the PHQ-9 or objected to the content of the items. No items required major modifications for better comprehension or cultural fit. For item 7, the concentration item, because most subjects had no newspaper or television, we substituted appropriate alternatives for each individual, such as housework, farm work, crafts, or conversation.

Scoring time was the time required to add 9 single-digit numbers, a matter of seconds. We instructed our raters to score a problem, such as fatigue, appetite, or sleep, according to its frequency regardless of whether the rater attributed the item to the depression, another disorder, or an environmental condition. Clinicians rarely disagreed with the clinical implications of the scoring of the PHQ-9, and we noted no pattern of overdiagnosis or underdiagnosis relative to clinical judgment. The proposed interpretations of total scores4 (minimal = 1–4, mild =5–9, moderate = 10–14, moderate-severe = 15–19, and severe = 20) for the U.S. sample appeared to apply equally well to this Honduran sample.

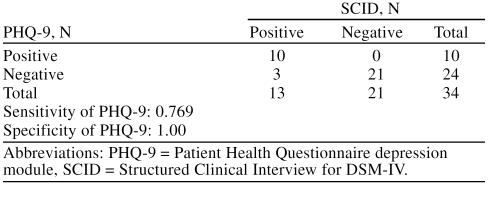

Rates of overt errors, such as item omissions, ambiguous answers, or incorrect addition, were minimal and consistent with standard data collection error rates. For the 34 subjects who completed both the PHQ-9 and the SCID mood disorders module, the PHQ-9 showed a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 100% (Table 1). In most cases, the person completing the SCID was not blind to the PHQ-9 results.

Table 1.

PHQ-9 Sensitivity and Specificity for Major Depression

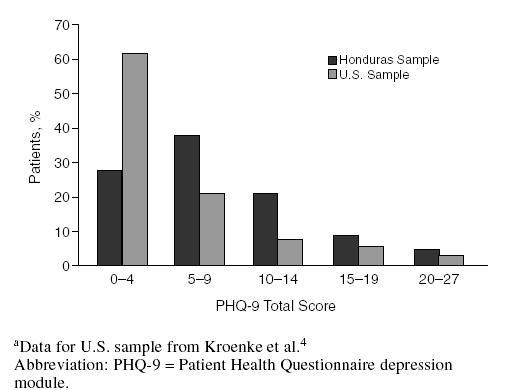

Figure 1 shows the distribution of PHQ-9 scores for the 199 subjects in the second wave of data collection compared with the distribution of a U.S. primary care sample (N = 580).4 In the Honduran sample, 15% met criteria for major depressive syndrome, compared with 7% in the U.S. sample. In the Honduran sample, 35% scored 10 or above, whereas in the U.S. sample, 17% scored 10 or above, suggesting that the Honduran sample was more than twice as likely to report clinically significant depressive symptoms. This U.S. sample included men and women, mostly insured, with at least some high school education.

Figure 1.

Distribution of PHQ-9 Total Scores Comparing the Honduras Sample (N = 199) With a U.S. Sample (N = 580)a

DISCUSSION

We found the PHQ-9 to be an easy measure to use for screening for depression in this rural Honduran population of mothers of young children. Training time was minimal because our raters had some clinical experience with assessing depression. Administration was straightforward, and subject acceptance was high. The content of the items was neither offensive nor confusing; on the contrary, most subjects with depression found the items informative. The raters, both U.S. and Honduran clinicians, likewise found the items clinically useful, and the overall scoring consistently agreed with their clinical judgment. The distribution of PHQ-9 scores in our Honduran sample is similar to the distribution in the U.S. primary care sample, except that a higher percentage of the Honduran sample reported mild depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score of 5–9). This suggests that the PHQ-9 functions similarly in both populations in spite of substantial demographic differences in the samples.

The small number of SCID interviews completed to test the criterion validity of the Spanish PHQ-9 limits this study. We were constrained by the number of trained SCID interviewers and our fixed length of stay during the brigades. Further data collection and analysis may amplify the current findings. For example, we plan to examine the distribution of PHQ-9 scores across raters to study whether there was substantial variability in the scoring patterns by the different raters.

CONCLUSIONS

Like the English PHQ-9, the Spanish PHQ-9 is an efficient and reliable screening measure for major depression. It is useful as a research measure for estimating the prevalence of major depression and as a clinical aid to the primary care clinician in rural Honduras. It is likely to be as useful in other Central and South American populations, both in the clinic and in the community.

Appendix 1

PHQ Depression Module (PHQ-9)a

Appendix 2

Cuestionario Sobre La Salud Del Paciente (PHQ-9)a

Footnotes

Shoulder to Shoulder provided the medical brigades through which these data were gathered. Pfizer Inc partially funded this research through an unrestricted educational grant.

Dr. Wulsin has been a consultant for and has received grant/research support from Pfizer. Dr. Somoza has received grant/research support from Pfizer and Schering-Plough.

REFERENCES

- Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K. Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:759–769. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, West S, Swindle R, et al. Similar effectiveness of paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:2947–2955. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Noel P, Cordes J, et al. Is this patient clinically depressed? J Am Med Assoc. 2002;287:1160–1170. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]