Abstract

Background:

Topiramate (TPM), a broad-spectrum antiepileptic drug, has been associated with neuropsychological impairment in patients with epilepsy and in healthy volunteers.

Objective:

To establish whether TPM-induced neuropsychological impairment emerges in a dose-dependent fashion and whether early cognitive response (6-week) predicts later performance (24-week).

Methods:

Computerized neuropsychological assessment was performed on 188 cognitively normal adults who completed a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, 24-week, dose-ranging study which was designed primarily to assess TPM effects on weight. Target doses were 64, 96, 192, or 384 mg per day. The Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery was administered at baseline and 6, 12, and 24 weeks. Individual cognitive change was established using reliable change index (RCI) analysis.

Results:

Neuropsychological effects emerged in a dose-dependent fashion in group analyses (p < 0.0001). RCI analyses showed a dose-related effect that emerged only at the higher dosing, with 12% (64 mg), 8% (96 mg), 15% (192 mg), and 35% (384 mg) of subjects demonstrating neuropsychological decline relative to 5% declining in the placebo group. Neuropsychological change assessed at 6 weeks significantly predicted individual RCI outcome at 24 weeks.

Conclusions:

Neuropsychological impairment associated with TPM emerges in a dose-dependent fashion. Subjects more likely to demonstrate cognitive impairment after 24 weeks of treatment can be identified early on during treatment (i.e., within 6 weeks). RCI analysis provides a valuable approach to quantify individual neuropsychological risk.

Classification of evidence:

This study provides Class II evidence that TPM-induced cognitive impairment is dose-dependent with statistically significant effects at 192 mg/day (p < 0.01) and 384 mg/day (p < 0.0001).

Topiramate (TPM) is an effective broad-spectrum antiepileptic drug (AED) with approved indications for partial onset and generalized epilepsy in children and adults and for migraine prophylaxis in adults. In studies of patients with epilepsy and in healthy volunteers, the distinct cognitive side effects associated with TPM have been well-described and studied.1

No prospective dose-ranging studies of TPM's effect on cognition, however, have been performed, making it difficult to determine specific dose-related risk to neuropsychological function. Further, group studies have not characterized individual risk, but rather have relied only on group comparisons. Understanding TPM's propensity to cause reversible cognitive impairment across a range of dosing levels is important, and the degree to which cognitive impairment may habituate over time within individual subjects will provide important data to inform prescribing practices.

As part of a 6-month placebo-controlled treatment study examining TPM dose effects on weight in obese but otherwise healthy subjects,2 computerized neuropsychological assessment was performed at baseline and 3 subsequent time points. Here we report neuropsychological results from that patient cohort and examine the extent to which early cognitive impairment is a reliable predictor of final neuropsychological outcome. In addition to traditional parametric approaches to examine group differences, we calculate reliable change indices (RCIs), which permit the assessment of significant cognitive decline to be quantified at the individual patient level.3

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The TPM obesity trial2 (study ID NCT00236613) was conducted at 17 US sites from September 2000 to July 2001. The trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating site and all subjects provided written informed consent prior to study entry.

Protocol.

Inclusion criteria included a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 to <50 kg/m2 or, if the subject also had controlled hypertension or dyslipidemia, a BMI of ≥27 to <50 kg/m2. Subjects were excluded due to recent weight change (>7 pounds in 3 months prior to enrollment), diabetes, poorly controlled hypertension, liver disease, renal dysfunction, or cardiovascular, endocrine, neurologic, or psychiatric disease. The trial was powered to show a 4% difference in body weight reduction with 90% power for active treatment compared to placebo, which was the primary obesity trial outcome variable.

A total of 385 subjects entered the double-blind phase of the obesity trial and were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1:1:1) to receive placebo (n = 76), 64 mg/day TPM (n = 76), 96 mg/day TPM (n = 78), 192 mg/day TPM (n = 76), or 384 mg/day TPM (n = 79) based on a computer-generated randomization schedule prepared by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC. Randomization was stratified by center using randomly permuted blocks of 5 to ensure equivalent numbers of subjects were assigned to each treatment condition. An Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) was used to randomly assign subjects to trial treatment, dispense study drug, and track subject dose changes. The IVRS was used to efficiently manage drug inventory while ensuring that no patient at the site had to be unblinded. Medication kits were labeled with a 2-part tear-off label, with one part then attached to the subject's case report form when the drug was dispensed.

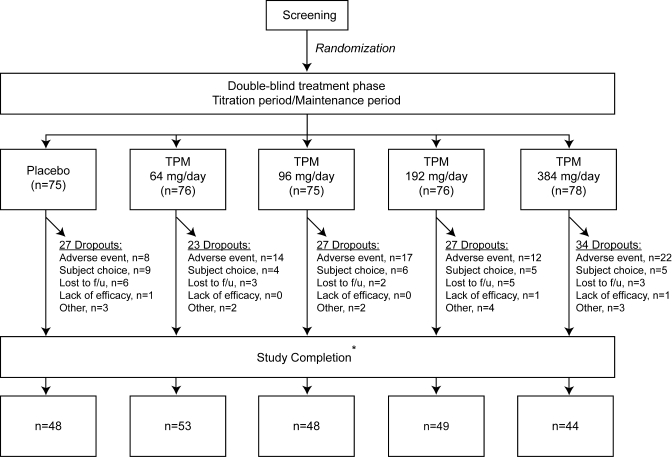

Of the 385 subjects randomly assigned to trial treatment, 380 subjects received at least 1 dose of study medication and contributed postbaseline safety data. The disposition of subjects in this safety population is depicted in figure 1. A total of 376 subjects received at least 1 dose of double-blind study medication and completed at least 1 postbaseline primary or secondary efficacy evaluation for the original obesity-related outcomes and comprise the intent-to-treat population. A total of 242 subjects completed all visits through week 24 (including the 12-week titration and 12-week maintenance period) and had evaluations at baseline and at day 155 (week 24) or later maintenance period, and provided 24-week data for the obesity-related study endpoints. Of these 242 subjects, 188 also had baseline and week 24 cognitive assessment data. It is this final group that forms the sample for this study. Demographic characteristics of this completer group are included in table 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of eligible patients included and excluded in the study.

*Includes subjects who completed all visits through week 24 and who completed all week 24 assessments. TPM = topiramate.

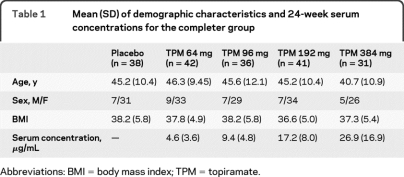

Table 1.

Mean (SD) of demographic characteristics and 24-week serum concentrations for the completer group

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; TPM = topiramate.

During titration, the initial dose was 16 mg/day during the first week and was increased to 32 mg/day in divided doses during week 2. Dosing was subsequently increased each week in 32 mg/day increments until target dosing was reached and the duration of the TPM titration ranged from 2 to 12 weeks. Compliance was determined by designated study personnel who maintained a log of all study drug dispensed and returned, and drug supplies for each subject were inventoried and accounted for throughout the trial by the research pharmacist.

Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery.

The Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery (CNTB) measures a broad range of cognitive abilities, and takes approximately 50 minutes to administer.2 The CNTB is a validated measure4,5 that has been used as a cognitive endpoint for clinical trials.5,6 CNTB subtests assess motor speed, attention and information processing speed, verbal learning and memory, spatial memory, language, and other spatial functions.5,6 The CNTB summary score was chosen as the primary cognitive outcome measure because it has been more extensively validated than subtest measures and has been reported in clinical and observational trials.4,6–8 Higher scores reflect better performance. CNTB subtest scores were examined in exploratory analyses.

Subjects were tested at baseline, week 6, week 12, and week 24. Because of the slow titration schedule, target doses were not obtained for the 2 higher doses at the 6-week timepoint. Since subjects reached their target doses at different times following study entry, there are group differences with respect to the duration in which subjects were at target dosings, with group differences present in the adaptation/habituation time after reaching target levels. The CNTB was administered to 344 subjects at baseline, and 188 subjects had CNTB testing at the 24-week study endpoint.

Statistical analysis.

All CNTB statistical analyses were performed after database lock, thereby maintaining the double-blind. Two approaches to data analysis were performed. The first is a traditional parametric approach examining group differences on the sample of subjects completing the 24-week trial. Completer analysis is a more appropriate approach to evaluating cognitive outcomes than intention-to-treat approaches.9 No experiment-wise control of type I error rate was performed because in the context of testing for difference in dose effects, we considered a type II error to be more relevant than a type I error, and because analysis of CNTB subtests was considered exploratory.

The second approach to CNTB summary score analysis employed RCIs. RCIs characterize whether performance change upon retesting exceeds what can statistically be attributed to test-retest variability, standard error of the test, and practice effects, thereby permitting the assessment of significant change at the individual patient level.3,10 RCIs were derived from the placebo control group based upon the SD of the difference scores between assessments, and incorporate a correction for expected improvement due to repeated assessment from the placebo group. As is common in the neuropsychological literature, we use 90% confidence intervals of the test-retest difference to characterize individual response. Subjects declining by more than this 90% criterion were considered to develop cognitive adverse events (AEs). We also examined the relationship of demographics and week 6 CNTB change score to RCI outcome (i.e., better/no change vs decline) using simple proportional odds.

RESULTS

Disposition of subjects in the safety population throughout the course of the initial obesity study and reasons for discontinuation are presented in figure 1. The safety population comprised all patients entering the main weight loss study who received medication regardless of whether they completed the trial or neuropsychological testing and who had at least 1 safety assessment. The frequency of adverse events leading to study withdrawal in the safety population was placebo = 8/75 (11%), 64 mg = 14/76 (18%), 96 mg = 17/75 (23%), 192 mg = 12/76 (16%), and 384 mg = 22/78 (28%). A comprehensive listing of all adverse events according to the standard typology is contained in the original obesity trial.2 For the purposes of this study reporting dose-dependent cognitive side effects, AEs leading to study withdrawal were reviewed without knowledge of treatment arm (D.W.L.) and classified as including a cognitive component or not.

The completer group (those who underwent CNTB testing at baseline and at 6 months) did not differ from noncompleters on demographic variables of age [44.8 (SD = 10.9) vs 45.6 (SD = 11.8), p = 0.46] or BMI [37.6 (SD = 5.4) vs 37.1 (4.6), p = 0.36]. The overall sample was predominately female (n = 324, 85%), and women were more likely to drop out of the study than men (p = 0.04).

Parametric analyses.

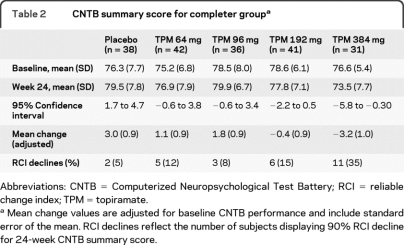

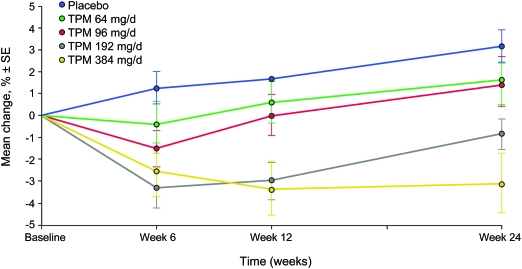

Means and standard deviations for baseline and 24-week CNTB performance with corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the difference scores are presented in table 2. Our primary analysis was the 24-week CNTB summary score across the 5 TPM dose conditions. This was analyzed using a 5-level analysis of covariance with baseline CNTB summary score as a covariate. A dose effect was observed (p < 0.0001). Adjusted mean differences and standard errors are presented in table 2. This pattern indicates the expected group level dose-dependent TPM effect on cognitive function with higher doses leading on average to poorer neuropsychological performance, and is illustrated graphically in figure 2.

Table 2.

CNTB summary score for completer groupa

Abbreviations: CNTB = Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery; RCI = reliable change index; TPM = topiramate.

Mean change values are adjusted for baseline CNTB performance and include standard error of the mean. RCI declines reflect the number of subjects displaying 90% RCI decline for 24-week CNTB summary score.

Figure 2. Change over time for Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery summary score (% correct) for completer group.

TPM = topiramate.

Pairwise group comparisons examining the simple main effects within each TPM dose at 24 weeks relative to baseline revealed no drug effect for TPM 64 mg or for TPM 96 mg, although TPM effects were present for doses of 192 mg (p < 0.01) and 384 mg (p < 0.0001).

Individual CNTB subtest differences are indicated in table 3. The CNTB subtest most sensitive to TPM dose was visual memory, with significant performance declines beginning at the 96 mg dose level. Delayed recall for paired associates and simple reaction time declined at the 192 TPM dose, with additional significant effects for paired associate learning, delayed word list learning, choice reaction time, and CNTB Boston Naming at the TPM 384 mg condition.

Table 3.

Significant CNTB subtest differences for each dosing level compared to placebo at 24-week endpointa

Abbreviations: CNTB = Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery; TPM = topiramate.

√ indicates that the result for the TPM group differs from placebo, i.e., the actual mean difference is not zero, based on the 95% confidence interval not including zero.

Reliable change indices.

RCI results are displayed in table 2, and illustrate TPM dose effects when observed at the individual subject level. Relative to the 5% of placebo subjects who demonstrated neuropsychological decline, the number of subjects taking TPM who declined as defined by the 90% RCI ranged from 8% to 12% in the 2 lower TPM dose conditions to 35% at the highest TPM dose studied.

If subjects displaying RCI declines are considered to have developed treatment-emergent cognitive side effects, then this risk can be expressed by the number needed to harm (NNH). Using this approach, 64 mg NNH = 15.1, 96 mg NNH = 32.6, 192 mg NNH = 10.7, and 384 mg NNH = 3.3.

Outcome prediction.

We next examined the relationship of various demographics including age, sex, BMI, baseline score, and week 6 CNTB change score to RCI outcome (i.e., better and no change vs decline). No effects were observed for age (p = 0.13), BMI (p = 0.06), or baseline CNTB score (p = 0.52). However, 6-week CNTB change score related to the 24-week cognitive RCI outcome (p < 0.0001). Subjects in the 64 mg and 96 mg groups reached their final targets by the 6-week timepoint, although subjects in the 192 mg and 382 mg groups were still in the process of titration at the 6-week assessment. Because of this difference, we formed 2 subject groups (lower dose at target levels, higher dose still at titration) and repeated the analysis, and found effects for both subgroups (TPM 64/96 mg, p = 0.007; TPM 192/382 mg, p = 0.002) indicating that an effect on the total CNTB score after 24 weeks was predictable based upon the 6-week assessment.

Plasma concentrations.

Because of interindividual variability in TPM blood concentrations at a given dose,11 we performed post hoc analyses examining serum levels independent of dose to CNTB total score and also whether blood levels were associated with RCI decline at the 24-week endpoint. A correlation was observed (−0.23, p = 0.004) between CNTB total score and blood levels. This relationship was also present using serum concentrations to predict individual RCI declines using t test analysis (t = −3.0, p = 0.004).

DISCUSSION

This study indicates that neuropsychological impairment associated with TPM emerges in a dose-dependent fashion. Compared to placebo, no evidence of neuropsychological impairment on the CNTB summary score was present following 24 weeks of treatment at 64 mg/day and at 96 mg/day. At 6 weeks, there was modest neuropsychological decline evident in the CNTB summary score when assessed at 96 mg/day but this improved with time. Evidence of dose-dependent neuropsychological impairment at 24 weeks was observed at the 2 higher TPM doses of 192 mg/day and 384 mg/day.

Higher dosages led to detectable and more pronounced changes not only on the primary CNTB outcome measure, but also in several cognitive domains. However, not all cognitive domain tests were affected (table 2). The first cognitive domain affected in a dose-dependent fashion was visual memory at 96 mg/day. At 192 mg, delayed paired associated learning and simple reaction time were also affected. At the highest dosage of 384 mg/day, significant cognitive drug effects were observed on multiple memory measures, visual naming ability, and reaction time.

Because side effects associated with medication often habituate over time, we investigated whether neuropsychological performance obtained following 6 weeks of TPM treatment was associated with neuropsychological outcome at the 24-week endpoint, and a strong and significant relationship was observed. Subjects who are likely to experience the greatest cognitive decline can be identified early in treatment, which will guide the clinician in identifying patients with the greatest vulnerability for cognitive side effects soon after initiating TPM.

There are several limitations to this report. The first is that our results are based upon only those subjects completing the trial (efficacy subset analysis). We have argued previously that intention-to-treat analyses are not appropriate to estimate magnitude of neuropsychological effect in AED trials.9 If a subject experiences an adverse event during titration in which the AED is discontinued, neuropsychological testing cannot readily be obtained prior to changing, stopping, or reducing the AED dose. Even if testing is conducted before drug change, mismatches will occur because the patient has not reached target dosing, and different test-retest intervals will be present which will alter the practice effects. Our findings are appropriate to characterize neuropsychological risk for patients who tolerate drug initiation and maintenance.

There were study dropouts in the overall safety population related to cognitive AEs of 5% at TPM 64 mg, and 11%–12% at TPM 96 mg, TPM 192 mg, and TPM 384 mg. Thus, the frequency of cognitive impairment as defined by RCI is an underestimate of the overall risk since the dropouts due to cognitive AEs are not included. Although self-reported cognitive AEs are not equivalent to RCI-defined decline, if self-reported AEs are considered as reasonable proxy for cognitive decline, then RCI and cognitive AEs together will provide a general estimate of TPM-related cognitive impairment. Combining RCI and cognitive AEs associated with study discontinuation yields the following estimates of cognitive impairment: TPM 64 = 9/76 (12%), TPM 96 = 12/75 (16%), TPM 192 = 14/76 (18%), TPM 394 = 20/78 (26%).

The original obesity protocol did not document the precise relationship between dosing and CNTB testing, so it is unclear if subjects were tested at the same time of day for each assessment or whether the interval between medication dose and testing was constant across subjects. If not consistent, then the results of the trial would be biased toward the null hypothesis. Fortunately, the half-life of TPM is sufficiently long (mean = 21 hours) so as to minimize these potential time differences on cognitive assessment.

Because experience with the CNTB in clinical trials is more limited than traditional neuropsychological tests, the generalizability to real-world behaviors is more difficult. This is particularly true for the 96 mg condition, in which parametric analyses suggested no CNTB summary score change although a significant decline was observed on the visual memory task. Thus, despite the absence of a significant effect on the primary cognitive outcome, there appears to be some cognitive effects of 96 mg TPM on secondary measures that is not reflected in the global CNTB summary score. However, the clinical significance of this is not established and should also be interpreted within the context of the type I vs type II error tradeoff. As with other behavioral AEs, there is typically considerable individual variability regarding real-world effects, and these will likely vary as a function of expectations, job requirements, and deficit awareness.

RCI analyses to characterize neuropsychological treatment risk are a significant strength of this report and provide an empirical approach to quantify individual risk of cognitive decline. Classifying individual risk has often relied on tabulating the frequency with which subjects display a magnitude of post-treatment change that is expressed as a function of the SD. This approach, however, relies on group performances from a single timepoint. The RCI, in contrast, is based upon difference score characteristics including the test-retest reliability of the measure and the standard error of the test while incorporating a correction for practice effects, and thus is better suited to characterizing cognitive decline than single observation SD. We suggest that RCI analyses be considered as an appropriate metric to quantify treatment risk to cognitive function and calculate NNH when neuropsychological outcome measures are employed.

Using RCI analysis, the risk of cognitive decline for study completers at the 64 mg and 96 mg dosing ranges from 8% to 12%. At 192 mg, approximately 15% of the subjects demonstrated significant RCI declines and at 384 mg, 35% of the subjects had declines. These findings parallel the group results, but permit better communication of individual risk when treatment considerations are being discussed. These results establish increased individual risk of cognitive impairment at the highest dose examined, and also indicate that there are individuals who may be particularly susceptible to TPM cognitive side effects at low or high doses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank C.V. Damaraju and Steve Ascher for statistical support.

Footnotes

- AE

- adverse event

- AED

- antiepileptic drug

- BMI

- body mass index

- CNTB

- Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery

- IVRS

- Interactive Voice Response System

- NNH

- number needed to harm

- RCI

- reliable change index

- TPM

- topiramate

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Loring serves/has served on scientific advisory boards for the Epilepsy Foundation and Sanofi-Aventis; serves as a consulting editor for the Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, as contributing editor for Epilepsy Currents, and on the editorial board of Neuropsychology Review; serves as a consultant for NeuroPace, Inc., Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB; receives royalties from the publication of Neuropsychological Assessment, 4th ed. (Oxford University Press, 2004) and INS Dictionary of Neuropsychology (Oxford University Press, 1999); estimates that 50% of his clinical effort involves neuropsychological testing; and receives research support from NeuroPace, Inc., SAM Technology Inc., Myriad Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Novartis, the NIH/NINDS, and the Epilepsy Foundation. Dr. Williamson is a salaried employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; and receives stock and stock options from Johnson & Johnson, parent company of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. Dr. Meador serves on the editorial boards of Neurology and Behavior & Neurology, Epilepsy and Behavior, Epilepsy Currents, Epilepsy.com, and the Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology and on the Professional Advisory Board for the Epilepsy Foundation; received travel support from Sanofi-Aventis; and received research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai Inc., Marinus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Myriad Genetics, Inc., NeuroPace, Inc., Pfizer, SAM Technology Inc., Schwartz Pharma (UCB), the NIH/NINDS, and the Epilepsy Foundation. Dr. Wiegand is a salaried employee of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Services LLC. Dr. Hulihan is a salaried employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; and receives stock and stock options from Johnson & Johnson, parent company of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

REFERENCES

- 1. Loring DW, Marino S, Meador KJ. Neuropsychological and behavioral effects of antiepilepsy drugs. Neuropsychol Rev 2007;17:413–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bray GA, Hollander P, Klein S, et al. A 6-month randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of topiramate for weight loss in obesity. Obesity Res 2003;11:722–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Veroff AE, Bodick NC, Offen WW, et al. Efficacy of xanomeline in Alzheimer disease: cognitive improvement measured using the Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery (CNTB). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1998;12:304–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cutler NR, Shrotriya RC, Sramek JJ, et al. The use of the Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery (CNTB) in an efficacy and safety trial of BMY 21,502 in Alzheimer's disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 1993;695:332–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Veroff AE, Cutler NR, Sramek JJ, et al. A new assessment tool for neuropsychopharmacologic research: the Computerized Neuropsychological Test Battery. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1991;4:211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cutler NR, Veroff AE, Frackiewicz EJ, et al. Assessing the neuropsychological profile of stable schizophrenic outpatients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996;8:423–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brass EP, Polinsky R, Sramek JJ, et al. Effects of the cholinomimetic SDZ ENS-163 on scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment in humans. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;15:58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meador KJ, Loring DW, Hulihan JF, et al. Differential cognitive and behavioral effects of topiramate and valproate. Neurology 2003;60:1483–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chelune GJ, Naugle RI, Lüders H, et al. Individual change after epilepsy surgery: practice effects and base-rate information. Neuropsychology 1993;7:41–52 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johannessen SI, Patsalos PN, Tomson T, Perucca E. Therapeutic drug monitoring. In: Engel J, Jr, Pedley TA, eds. Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook, vol 2, 2nd ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:1171–1183 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.