Abstract

Background:

The mortality of patients with Guillain Barré syndrome (GBS) has varied widely with rates between 1-18%. Death results from pneumonia, sepsis, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and less frequently due to autonomic dysfunction or pulmonary embolism. There are only few studies which have used a large sample and have in detail analyzed the circumstances relating to death and the prognostic factors for the same in a cohort, including only mechanically ventilated patients.

Objective:

The objective of our study was to analyze the circumstances and factors related to mortality in mechanically ventilated patients of GBS.

Materials and Methods:

Case records of patients of GBS, satisfying National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) criteria, and requiring mechanical ventilation from 1984 to 2007, were analyzed.

Results:

A total of 273 GBS patients were managed with ventilatory support (190 men and 83 women) during the period. Besides symmetrical paralysis in all patients, bulbar palsy was present in 186 (68.1%), sensory involvement in 88 (32.2%) and symptomatic autonomic dysfunction in 72 (26.4%) patients. The mortality was 12.1%. The factors determining mortality were elderly age group (P=0.03), autonomic dysfunction (P=0.03), pulmonary complications (P=0.001), hypokalemia (P=0.001) and bleeding (P=0.001) from any site. Logistic regression analysis showed the risk of mortality was 4.69 times more when pneumonia was present, 2.44 times more when hypokalemia was present, and 3.14 times more when dysautonomia was present. The odds ratio for age was 0.97 indicating that a higher age was associated with a higher risk of mortality.

Conclusions:

Ventilator associated pulmonary complications, bleeding and hypokalemia especially in elderly patients require optimal surveillance and aggressive therapy at the earliest for reducing the mortality in this group of GBS patients.

Keywords: Guillain Barré syndrome, intensive care, mechanical ventilation, mortality

Introduction

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute autoimmune polyradiculoneuropathy associated with significant morbidity. During hospitalization, some of the patients of GBS are intubated for respiratory failure, and their course can be further complicated by dysautonomia, and various intensive care units (ICU) related complications.[1] The outcome of GBS has varied widely in published series with mortality rates ranging between 1-18%,[2] and remaining higher (12-20%) in those who required mechanical ventilation.[3] The mortality in ventilated patients was higher (20%) in the study by Lawn et al.[1] and 38.3% in the series by Taly et al.[4] Death in GBS results from pneumonia, sepsis, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and less frequently autonomic dysfunction or pulmonary embolism.[1] The factors which have been found to have an impact on mortality have been age,[3,5] specific antecedent events[5] rapidity of progression,[6] sensory disturbances, ventilatory requirement,[7] bulbar dysfunction,[8] dysautonomia,[3,9,10] sepsis and pulmonary complications.[3,10] However, many of these predictors of mortality in literature have included the general cohort of GBS patients, or a small subgroup of mechanically ventilated patients. Few studies have been published from single academic institutions with detailed analysis of the circumstances relating to death and the prognostic factors for the same in a large cohort of mechanically ventilated patients of GBS. As mortality in ventilated patients is higher, the need for finding prognostic factors in such a cohort of patients is imperative .

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the case records of all consecutive patients of GBS ventilated in the neurology ICU of a tertiary care institute for neurosciences during a period of 23 years (July 1, 1984 and June 30, 2007). The study had approval of the institute ethics committee. Patients satisfying the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) criteria for GBS were included.[11] These patients who presented themselves to the emergency department were initially evaluated by the neurology team, and admitted to the wards with close monitoring for any impending respiratory failure or autonomic dysfunction. At the earliest sign of respiratory compromise, the patients were evaluated by the neuroanasthesia team of the institute, and shifted for mechanical ventilation. The criteria for selection of mechanical ventilation were features of hypoxia, vital capacity <15 ml/kg, PaO2 of less than 70 mmHg and PaCO2 of >45 mmHg.[4] The various treatment modalities, such as, plasmapheresis, immunoglobulin (IVIG) or steroids were ordered by the treating neurologist taking into consideration the availability of these treatments in the institute at that point of time, the age, hemodynamic parameters and affordability of the patient. Patients 19 to 33 [Table 1] were in the decade between 1984 and 1997 before the advent of Plasma exchange at this centre and hence received steroids, Cyclophosphamide[12,13] or only supportive treatment as decided by the treating neurophysician. Small volume Plasmapheresis was ordered when patients had autonomic dysfunction and in very young or very old patients, or occasionally when the large volume kits were not available. In small volume plasma exchange, 10% of blood volume was collected through a peripheral vein in a plastic double bag which had citrate phosphate dextrose adenine (CPDA) as an anticoagulant (14 ml CPDA for 100 ml blood). This was centrifuged at 5000 G and the plasma was removed. Equivalent amount of saline was added to the red cells and infused to the patient. The procedure was done 10-15 times depending on the patient's improvement levels. Small volume exchange has been found to be effective in reducing the time to recovery, duration of ventilation and number of complications, though overall mortality was not affected.[14] In large volume plasma exchange, 200-250 ml/kg of plasma was exchanged in 4-5 sessions of 40-50 ml/kg. Patients who were started on large volume plasmapheresis were given replacement fluids in the form of fresh frozen plasma, human albumin or saline. All these patients were started on prophylactic heparin given daily, along with neuro rehabilitative care, and were closely monitored for any complications. The monitoring equipments in the ICU include pulse oximetry, continuous cardiac tracing, and noninvasive blood pressure recording along with the measurement of the respiratory system mechanics through the mechanical ventilator. The records were analyzed to identify those who died in the hospital as a result of GBS. Further, death due to GBS in the hospital was was considered only if death occurred in association with ongoing symptoms of GBS, or in the presence of prolonged immobility and respiratory dysfunction.[1] Details of demographic data, antecedent events, progression of symptoms, laboratory parameters and investigations done to exclude the secondary causes, ICU complications, treatment details were entered in a pre designed form. Electrophysiological parameters could not be analyzed in the patients who died, as the nerve conductions were routinely done only after the patients were stable and could be safely transferred to the electrophysiology lab. Patients who were kept in ICU for only observation and monitoring and with incomplete case records were excluded from the study.

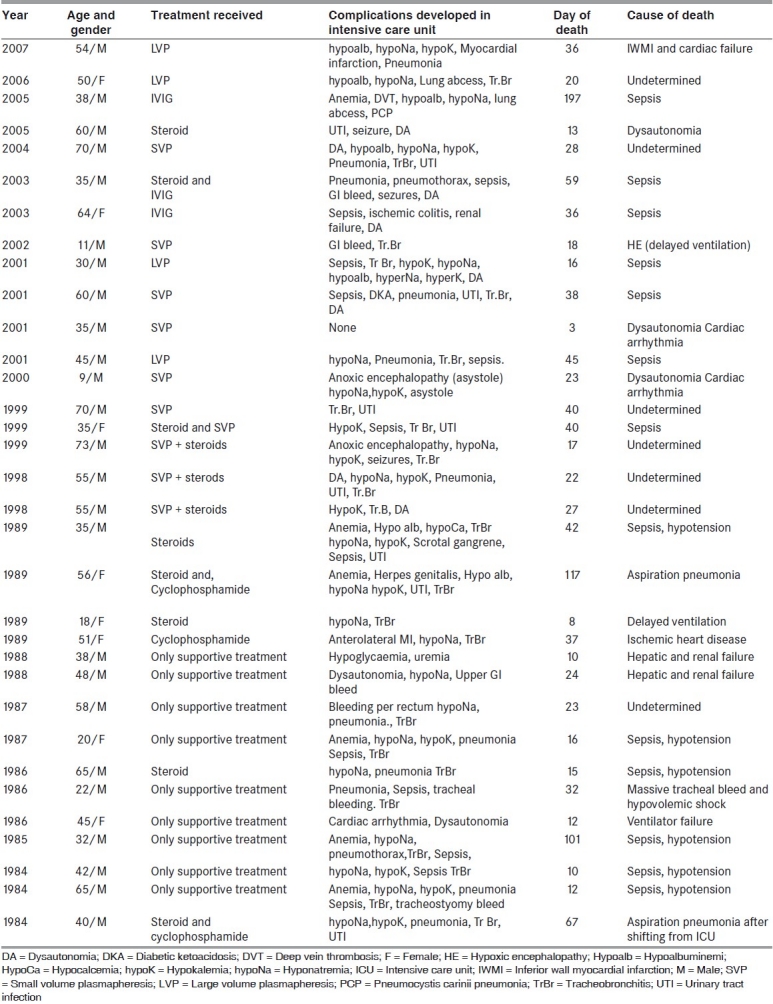

Table 1.

Clinical profile of the patients who died in the study

Definition of terms

The degree of weakness was calculated for each patient as per the British Medical Research council (MRC) scale (5 = normal; 4 = opposes resistance; 3 = opposes gravity; 2 = moves joint; 1 = flicker; and, 0 = absent and accepting the lowest score for each limb. Severe weakness was defined as MRC grade ≤ 2.[15]

Autonomic dysfunction noted were: Cardiac arrhythmias, lability of the blood pressure, abnormal hemodynamic response to drugs, electrocardiographic abnormalities, pupillary dysfunction, sweating abnormalities, urinary retention and gastrointestinal dysfunction.[16]

Bulbar palsy was defined if the patient had dysphagia, nasal regurgitation of fluids or nasal twang to voice.

-

Complications in Intensive Care Unit:

- Electrolyte abnormalities; Hyponatremia: Sodium < 135 mmols/L, Hypokalemia: K < 3.5 mmols/L.

- Nutritional: Hypoalbuminemia = albumin < 35g/L, anaemia = Haemoglobin < 120 g/L. (at least on 2 occasions).

- Pulmonary complications: Pneumonia, collapse, pneumothorax as evidenced by abnormality on chest radiographic examination.

- Sepsis: Fever, tachycardia, increased leukocyte count, bacteraemia (blood culture) or central access device contamination as defined by positive pathogenic microbial culture (any two or more of the above features in combination).

- Day of death: Computed from the onset of illness.

- Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software (Version 11.0). Univariate analysis was done using independent sample t test for continuous variables and Fischer's exact test for categorical variables. The variables which emerged as significant in univariate analysis, were used for multivariate analysis using logistic regression analysis, to find-out which variables were helpful in predicting the mortality.

Results

A total of 273 GBS patients were managed with ventilatory support (190 men and 83 women) during the period. Their age ranged from 1 year to 84 years (33.6 ± 21 years). Thirty three patients (12.1%) (25 men and 8women) died between 3 and 197 days of onset of illness. Their age ranged between 9 and 73 years. Antecedent events in the preceding 4 weeks were recorded in 20 out of the 33 patients who died. These included fever, diarrhoea, respiratory infection, vaccination-, surgery, etc. Besides symmetrical paralysis in all patients, bulbar palsy was present in 186 (68.1%), sensory involvement in 88 (32.2%) and symptomatic autonomic dysfunction in 72 (26.4%).

Description of the fatal cases

The cause of death and various complications in these patients are depicted in Table 1. associated illnesses at the time of admission included diabetes mellitus (patients 10,16and 22) pulmonary tuberculosis (in patient 17 for which he was on treatment), Hansen's disease on treatment (patient 23) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (patient 27), retrovirus positivity (patient 3), hepatitis B antigen positivity (patient 21) and pancytopenia of probable drug induced etiology (patient 32). Patient 7 developed bleeding per rectum and was diagnosed with ischemic colitis. He underwent hemicolectomy, and developed sepsis and multiorgan failure leading to death. Lack of timely ventilation led to cerebral anoxia and death in 2 patients (patients 8 and 21). The most common cause of death was sepsis. The death was sudden and unexpected in the presence of existing complications in patients 2, 5, 14, 16, 17, 18 and 25; and, could have been due to myocardial infarction, dysautonomia leading to cardiac arrhythmias or pulmonary embolism. Among these patients 5, 17 and 18 had definite evidence of dysautonomia. Patient 20 suffered from aspiration pneumonia. Patient 32 had a massive bleeding from the tracheostomy site and died.

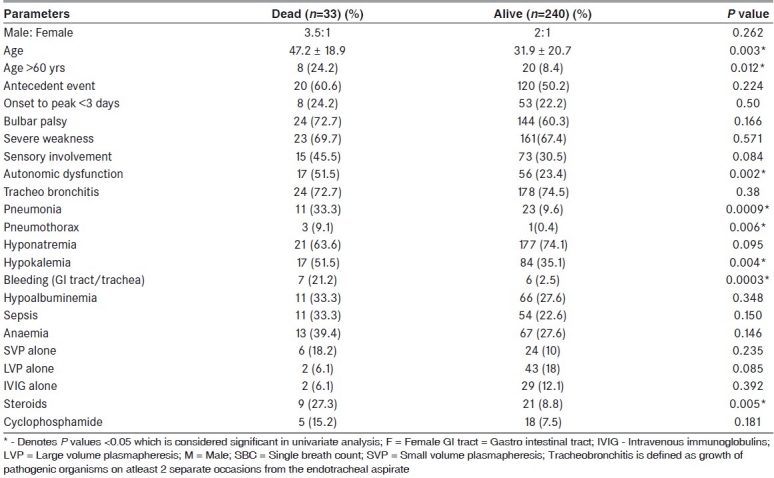

Prognostic factors for fatal Guillain Barré syndrome

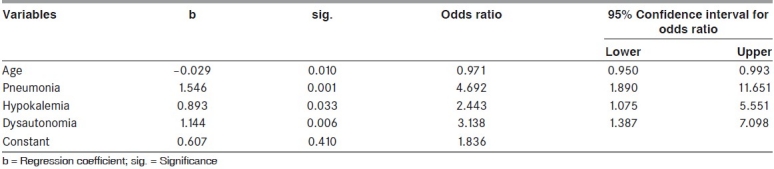

The overall mortality was 12.1% (33/273). In the period between 1995-2007, it was 10.4% (18/173) where as it was 15% (15/100) between 1984-1995. The prognostic factors determining mortality were analyzed [Table 2]. Among the variables significant in the univariate analysis, certain variables were omitted from the logistic regression analysis for want of sufficient number of cases/absence of patients in some of the categories. Logistic Regression analysis was used to find - out the variables that were helpful in predicting the mortality [Table 3]. Age, pneumonia, hypokalemia and dysautonomia were used to predict presence or absence of death, as they were significant in the univariate analysis and having sufficient number of cases. The logistic regression analysis resulted in significant regression coefficients for all these four variables. Age had a negative regression coefficient and the remaining three variables had positive coefficients. The odds ratio indicates that the risk of mortality was 4.69 times more when pneumonia was present, 2.44 times more when hypokalemia was present, 3.14 times more when dysautonomia was present. The odds ratio for age was 0.97 which indicated higher age was associated with higher risk of mortality.

Table 2.

Dead vs alive; demographic and clinical parameters and prognostic parameters in univariate analysis in the patients involved in the study

Table 3.

Results of logistic regression analysis (for the variables significant in the univariate analysis for predicting the mortality) of the patients in the study

Discussion

The present study found a mortality of 12.1% in the mechanically ventilated patients of GBS. The poor prognostic factors for mortality are elderly age group, presence of autonomic dysfunction, pulmonary complications, hypokalemia or bleeding while in the ICU.

The mortality rate varied in different studies ranging between 2% and 10% and remained higher (12-20%) in those who required mechanical ventilation.[2] Studies involving a similar cohort of patients have noted a much higher mortality in the past: 20% in the study by Lawn et al.[3], and 38.3% in the series by Taly et al.[4] The lower mortality in the present study could be due to the improved ICU care in the recent decade as observed by Krull et al.[17]

Elderly patients having higher mortality in the general cohort of GBS and in those undergoing mechanical ventilation is uniformly noted in literature.[1,3,9,18] In their study of 101 other patients with severe GBS admitted to the same ICU Lawn et al. had noted the patients who died were older (P = 0.006).[1]

Patients who died were more likely to have pulmonary disease, and the rate of death did not substantially change with introduction of specific treatment.[1,3,10] Dysautonomia[3,10,18] and sepsis[3,18] as a risk for mortality has uniform consensus in the literature, even though some other studies could not establish it with statistical significance.[1]

The study was retrospective in nature, and was carried out on patients who had been treated by multiple neurologists who might have followed different therapeutic options at a time when plasma exchange or IVIG was yet to be introduced. Although, Cyclophosphamide was no longer used in the latter decade, treatment options still varied from IVIG to small or large volume plasmapheresis. The lack of electrophysiological data in our study made it impossible to assess mortality among the various pathologic subsets of GBS, such as the acute inflammatory demyelinating or the acute motor or sensory axonal forms. Though the ICU care and ventilatory management have improved over the last two decades significantly, the incidence of mortality still remains high in mechanically ventilated patients. Ventilator associated complications in neurologically stable patients remain important management problems, particularly in elderly patients, and thus, they may require optimal surveillance of pulmonary functions and aggressive respiratory therapy at the first signs of pneumonia. A prospective study in a more uniformly controlled setting, with the objective of bringing out a validated score, might have an impact, both, on the therapeutic strategy during the initial stage of the disease, and on the rehabilitation program applied to the individual patient.

In conclusion, various electrolyte and ventilation associated complications are common in patients with GBS and mechanical ventilation. Identification and management of these factors is important for better outcomes in these severely affected patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Lawn ND, Wijdicks EF, Eelco FM. Fatal Guillain Barré syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:635–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng KK, Howard RS, Fish DR, Hirsch NP, Wiles CM, Murray NM, et al. Management and outcome of severe Guillain Barré syndrome. Q J Med. 1995;88:243–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alshekhlee A, Hussain Z, Sultan B, Katirji B. Guillain-Barré syndrome Incidence and mortality rates in US hospitals. Neurology. 2008;70:1608–13. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310983.38724.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taly AB, Gupta SK, Vasanth A, Suresh TG, Rao V, Nagaraja D, et al. Critically ill Guillain Barré syndrome. J Assoc Phys India. 1994;42:871–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Italian Guillain Barré Study Group. The prognosis and main prognostic indicators of Guillain Barré syndrome: A multicentre prospective study of 297 patients. Brain. 1996;119:2053–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Guillain Barré syndrome study group. Plasmapheresis and acute Guillain Barré syndrome. Neurology. 1985;35:1096–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernsen RJ, Jacobs HM, de Jager AE, Van der Meche FG. Residual health status after Guillain Barré syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:637–40. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durand MC, Porcher R, Orilkowiski D, Aboab J, Devaux C, Clair B, et al. Clinical and electrophysiological predictors of respiratory failure in Guillain Barré syndrome: A prospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:1021–8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chio A, Cocito D, Leone M, Giordana MT, Mora G. Guillain-Barré syndrome: A prospective population based incidence and outcome survey. Neurology. 2003;60:1146–50. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055091.96905.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koeppen S, Kraywinkel K, Wessendorf TE, Ehrenfeld CE, Schürks M, Diener HC, et al. Long-term outcome of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Neurocrit Care. 2006;5:235–42. doi: 10.1385/NCC:5:3:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asbury AK, Cornblath DR. Assessment of current diagnostic criteria for Guillain Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol (Suppl) 1990;27:521–4. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sylvia iannello in Guillain-Barré syndrome: Pathological clinical and therapeutic aspects. USA: Nova Biomedical Books; 2004. p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahuja GK, Mohandas S, Virmani V. Cyclophosphamide in Landry-Guillain-Barré syndrome. Acta Neurol (Napoli) 1980;2:186–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tharakan J, Jayaprakash PA, Iyer VP. Small volume plasma exchange in Guillain- Barré syndrome: Experience in 25 patient. J Assoc Phys India. 1990;38:550–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleywig RP, Van der Meche FG. Treatment related fluctuations in Guillain Barré syndrome after high dose immunoglobulins or plasmaexchange. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:957–60. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.11.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hund EF, Borel CO, Cornblath DR, Hanley DF, McKhann GM. Intensive management and treatment of severe Guillain-Barré syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1993;3:433–46. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krull F, Schuchardt V, Haupt WF, Mewes J. Prognosis of acute polyneuritis requiring artificial ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 1988;14:388–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00262894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schottlender JG, Lombardi D, Toledo A, Otero C, Mazia C, Menga G. Respiratory failure in the Guillain Barré syndrome. Medicina (B Aires) 1999;59:705–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]