Abstract

Culture-bound syndrome is a broad rubric that encompasses certain behavioral, affective and cognitive manifestations seen in specific cultures. These manifestations are deviant from the usual behavior of the individuals of that culture and are a reason for distress/discomfort. This entitles these manifestations for a proper labeling and subsequent management. However, the available information and literature on these conditions suggest that at least some of them are/have been more widely prevalent than being considered. This article presents a case for possible relabeling and inclusion of these conditions in the mainstream diagnostic systems based on the example of the dhat syndrome- a culture-bound syndrome from India. These conditions could be relabeled as functional somatic syndromes.

Keywords: Culture-bound syndrome, dhat syndrome, DSM-IV, ICD-10

INTRODUCTION

Culture-bound syndrome (CBS) is a broad rubric that encompasses certain behavioral, affective and cognitive manifestations seen in specific cultures. As per diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders - IV(DSM IV) (appendix I, p. 844), they denote recurrent, locality-specific patterns of aberrant behavior and troubling experience that may or may not be linked to a particular DSM-IV diagnostic category. Many of these patterns are indigenously considered to be “illnesses,” or at least afflictions, and most have local names... culture-bound syndromes are generally limited to specific societies or culture areas and are localized, folk, diagnostic categories that frame coherent meanings for certain repetitive, patterned, and troubling sets of experiences and observations.[1]

These manifestations are deviant from the usual behavior of the individuals of that culture and are a reason for distress/discomfort. This entitles these manifestations for a proper labeling and management.

Since these conditions are considered to be specific to certain regions, they are of concern and interest to the practitioners and the researchers from those regions. Because of this inherent assumption of cultural specificity of these conditions, they are considered to be alien to other cultures. Consequently, they hardly ever become area of interest for clinicians and researchers from these settings.

The current classification systems such as International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Conditions - 10 (ICD-10) (World Health Organization (WHO) 1992)[2] and DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 1994)[1] do not give guidelines to diagnose these culture-bound conditions in the main text. This is likely to result in arbitrary assumptions by the clinicians and researchers while dealing with them. In fact, these conditions do not find a place in the main text of DSM-IV and are placed in the appendix.

This article presents a case for inclusion of these conditions in the mainstream diagnostic classification because of theoretical and management implications. The argument is based on the available literature that demonstrates that the condition is/has been more widespread than assumed (as shown by the previous workers) and the available literature does not support the case for a “special labeling” of these conditions. Dhat syndrome has been chosen for the argument as this condition has been specified to be bound to the culture of author's training and clinical work. However, the argument is intended to be generalized to other ‘culture bound’ conditions as well.

Dhat syndrome has been specified as a CBS specific to the culture of the Indian subcontinent, especially India. Dhat derives from the Sanskrit word “dhatu” meaning “metal” and also “elixir”.[3] In this condition, the individual ascribes the symptoms of weakness, fatigability, sexual dysfunction, loss of virility and vitality to the loss of this valuable body fluid through the urine/nocturnal emission or masturbation.[4]

DHAT SYNDROME IS NOT RESTRICTED TO INDIAN SUBCONTINENT

It is assumed that dhat syndrome is a condition that is prevalent in the Indian subcontinent. However, Sumathipala et al.[5] have reviewed the history of the condition and have found it to be prevalent in different geographical regions of the world. It has been described in literature from China, Europe and Americas and Russia at different points of time in history.[6] Mention of semen as a “soul substance” could be found in the works of Galen and Aristotle who have explained the physical and psychological features associated with its loss.[7] Raguram et al. have cited the works of Beard, Hare and Maudsley linking semen loss with mental illness.[8]

CAN THE CHANGED SITUATION IN THE WESTERN WORLD BE EXPLAINED?

Over the years, the cases of the semen loss anxiety and the theories regarding the implication of the loss of seminal fluid due to indulgence in masturbation/sexual activity have gone into disrepute in many regions of the world. One could easily correlate this with the increasing advances in the field of medical science. An increasing scientific rigor with consequent increase in understanding and awareness into various issues and phenomenon has helped modify many locally held beliefs. People in many developed countries now have more scientifically based and plausible explanation for their bodily/psychic discomfort. It would be erroneous to say that the discomfort has disappeared from the lives of the people in these countries. Rather, the distress has assumed alternate manifestations. Also these manifestations continue to be both somatic and psychological. Conditions such as somatoform disorders are now recognized as validated conditions present across all regions of the world. Role of cultures in shaping these explanations and descriptions is not difficult to establish.[9] In fact, the case of unexplained somatic symptoms presents an interesting scenario in this context. While depression and anxiety are quiet common among these individuals, they are not an essential component of clinical presentation.[10] Factors such as doctor–patient interactions play a crucial role in the etiology of persistent unexplained symptoms.[11] The associations and attributions made by these patients are based on their (mis)attributions based on their perceptions and knowledge. Reattribution training has helped the general physicians to improve patient satisfaction and reduces the cost of treatment in some studies.[12]

WHY DO PATIENTS PRESENT WITH THE COMPLAINTS OF DHAT?

The members of a particular community, culture or region use the local vocabulary to express their feelings, moods and concerns. The idioms of expression used by them are based on the adjectives provided by the local language. Locally prevalent cultural norms, societal acceptance of certain issues and the role of the individual in society tend to govern the way in which one expresses himself. This applies to different feeling states including those of happiness, joy, sorrows or distress. It has been held that the individuals from the developing countries tend to somatize more than their western counterparts. This is not entirely correct assumption as presence of somatization among western populations has been well documented over the years.[13–15] Multicenter cross-national studies have shown strong association between somatic symptoms and psychological distress, which did not tend to vary across disparate cultures. However, cultural factors may influence the meaning attached to symptoms. Comparable rates of somatic complaints in the developing and the developed world were observed in the International Study of Somatoform Disorders conducted by WHO.[16]

Lipowski has reported three components of the presentation of the complaints by the patients: experiential; cognitive; and behavioral.[17] These components are governed by the locally prevalent attitudes and beliefs, the knowledge and awareness of the residents on the issue and the way the currently prevalent assumptions are reinforced or refuted so as to give way to new and more acceptable explanations. The authors from developing countries have observed that somatic complaints and symptoms take precedence over the symptoms given in the diagnostic manuals. The lack of appropriate adjectives for the expression of the mood, cognitive symptoms could be a reason for the same.[18] The local cultures have been found to be lacking in the direct equivalents for the terms depression or anxiety. It is vital to understand the culture-specific terminology used by patients in such settings. Also it is recommended to assess for mood and cognitive features of underlying depression and anxiety in those presenting with multiple somatic complaints. This is so because most of these patients do report cognitive and emotional symptoms of on being inquired. Missing the culturally specific idioms of distress could contribute to the under-recognition of depression and anxiety. An alternative could be to identify local concepts that may signify depression. Labels such as shenjing shuairuo (neurasthenia) in China, ghabrahat (anxiety) in India, pelo y tata (heart too much) in Botswana, and “nerves” in some Latin American and South African societies are described as local illness categories that overlap with depression.[19–22]

The widely prevalent cultural beliefs and the overwhelming importance given to certain issues tend to provide the individuals with the avenues to express their mood, cognitive and bodily symptoms. In context of dhat, the local beliefs tend to emphasize the seminal fluid as source of vitality and virility. Hence, loss of this fluid (albeit non-pathological) provides individuals from these cultures a plausible explanation for the experiences of distress. This attribution helps verbalized expression of need for help. This attribution is strengthened by its acceptance among others from the same cultural background including certain traditional and faith healers. Lack of appropriate knowledge on the physiological processes helps these beliefs to persist in the community. Advertisement for need to treat such conditions also helps validate the belief system.

DOES CULTURE IMPACT ONLY THE CULTURE-BOUND SYNDROMES?

Cultural factors have been shown to influence the presentation of various psychiatric disorders. Role of culture has been studied in disorders such as schizophrenia, major depression, anxiety disorders and attention deficit hyperactive disorder.[9,23] In the context of psychiatric disorders, cultural influence is evident at multiple levels. First, culture and society shape the meanings and expressions people give to various emotions.[24] Second, cultural factors determine which symptoms or signs are normal or abnormal.[25] Third, culture helps define what comprises health and illness.[18] Finally, it shapes the illness behavior and help seeking behavior.[26] So, it would not be erroneous to conclude that cultural influence on psychiatric disorders includes conditions other than CBS.

COULD THERE BE ANOTHER EXPLANATION FOR DHAT SYNDROME?

The current view on the dhat syndrome describes it as a culture-bound condition restricted to certain cultures. However, there is a need to relook at this condition as a functional somatic presentation of universal distribution- a manifestation that has been modified in certain cultures by the improved knowledge and awareness; and continues to manifest in others in its original form in absence of such knowledge and awareness.

Mumford studied the patients of dhat syndrome presenting in the outpatient setting in a developing Asian country. The dhat complaint was reported equally by the men attending medical clinics and by the patients with “functional” and “organic” diagnoses. It was strongly associated with depressed mood, fatigue symptoms, and a DSM-III-R diagnosis of depression. The findings of the study suggest dhat to be a culturally determined symptom associated with depression rather than a CBS.[6]

Malhotra and Wig reported that respondents in the study belonging to social class I discussed sex freely when compared with lower social classes. Also they were less likely to see physical causes for semen loss. People in social class IV were more likely than those of any other group to see nocturnal emission as abnormal. They were also least likely to see psychological persuasion as a mode of treatment for it. The authors explained the symptom as a consequence of the information and knowledge base of the individuals from the different social groups.[27] Chadha in his study found around half of the cases of dhat to be having depressive disorder, 18% to be having anxiety disorder and 32% to be having somatoform disorders.[28]

Dewaraja and Sasaki found that half of the patients with sexual dysfunction in a clinic-based sample in Sri Lanka attributing their symptoms to semen loss had somatic symptoms and a third had sexual deficiencies. This observation also suggests a role of knowledge and locally prevalent beliefs in explanation of the condition. The authors attempted to replicate the findings in Japan but were not able to do so. A higher awareness of the individuals regarding the role of semen and body vitality was put forth as the explanation for this observation.[29]

Bhatia, while studying 60 cases of CBSs seen in psychiatry out-patient department from India, found depression to be the most commonly associated psychiatric disorder in cases of dhat syndrome.[4] It could have been possible that the cases seen by the author were having semen loss anxiety as one of the manifestations of the underlying psychiatric disorder like depression and anxiety. However, patients’ knowledge and awareness shaped the semen loss as the presenting complaint and main area of concern.

There is a need to label the condition of dhat syndrome as a functional somatic syndrome. It should no longer be considered restricted to/as a manifestation of a particular culture. The findings from the previous literature on the condition suggests that the condition is not restricted to a particular culture type and has been found in different cultures. Disappearance of a particular manifestation of distress from some regions should not make it ‘culture bound’. Various other medical conditions have also seen a change in distribution pattern across world.

The frequently associated co-morbidity of the psychiatric disorders like depression, anxiety and somatization disorders reported in the available studies on dhat syndrome suggests that the condition could be a presenting form of these underlying psychiatric disorders. Depression, anxiety and somatization are all well known to present with bodily symptoms. Attribution of the underlying distresses to the easily observable and locally acceptable beliefs should not lead to a specific and distinct labeling of the distress. One must keep in mind the role of the culture in manifestation and management of such cases. However, this recommendation holds valid for all the psychiatric conditions. It seems uncalled for to label certain manifestations of distress as CBS and treat them as exotic/alien phenomenon.

Perme et al. have argued for a similar case. While studying 29 patients with dhat syndrome and 32 medical controls, they found that patients with dhat syndrome have significantly different illness beliefs and behaviors compared to controls and have similarities with other functional somatic syndromes.[30] Thus, one could argue for a case for inclusion of dhat syndrome as a functional somatic disorder rather than restricting it to a CBS.

There is a need to have a relook at the other CBSs and place them under rubrics of functional affective, functional somatic and functional behavioral conditions in the upcoming revisions of the diagnostic manuals.

NEED TO RELOOK, RELABEL AND INCLUDE THE CULTURE-BOUND SYNDROMES

The current version of DSM-IV has included the cultural underpinnings of the presentations of various mental and behavioral conditions in the text descriptions of the individual disorders. Also, it has incorporated the description of the CBS and the outline for assisting the clinicians in systematic evaluation of these conditions in its glossary section.[1] This approach highlights the acceptance of the importance of the cultural variables in shaping the psychiatric conditions and their management. Similarly, ICD-10 has described some of these conditions in the chapter F4.[2]

Authors like Wig (1994) and Littlewood (1996) have proposed the change in the current diagnostic classifications to shift the conditions currently included under the rubric of CBS to the group considered to be more widely prevalent.

One could easily draw the parallels from other psychiatric conditions considered to be prevalent all over the globe. Although these psychiatric disorders would be classified under the same diagnostic categories, there could still be differences in their manifestation and presentation in different cultures. These differences are shaped by the locally prevalent cultural beliefs, attitudes and knowledge among other factors. The patient of paranoid schizophrenia would be harboring a delusional belief of being persecuted against. However, it would not be surprising to find a variation in the content of this delusion. Such variations are shaped by the cultural and individual differences, part of which is governed by the knowledge and the understanding of the condition.[9] This would not change the diagnosis, although one would need to be aware of the local cultural nuances for the better understanding and the management of the case.

With the increasing globalization, the ‘culture bound’ cases are being seen by the clinicians in different cultures and geographical regions. Separately categorizing CBSs is unlikely to improve the management of these conditions. Rather, such an approach could impede the understanding of these conditions as researchers from other cultures and countries might consider it irrelevant to study these conditions because of their ‘culture specificity’.

The concerns of the Americans and Europeans during the 19th century were not much different from the concerns of the Asians in the present times. The limited awareness of some populations on certain issues related to the health and illness coupled with the locally prevalent beliefs and attitudes might have led to persistence of these issues in some societies. One of the ways forward could be to consider these as manifestations that have not ceased to manifest in certain cultures. The change observed in certain regions is a result of improved knowledge and changed belief system. This ahs lead to a change in traditional labeling patterns.[31]

Labeling these conditions a culture-bound condition is probably one of the reasons behind limited published literature on them. This is evident in case of dhat syndrome as there has been no published randomized trial of interventions for this condition. This impedes the progress in the understanding of management of this conditions. More research on dhat syndrome would not only help these regions with management of these conditions but also provide a better understanding in the functional somatic conditions. Researching how a once widely prevalent functional somatic condition became restricted to certain cultures is likely to come out with some interesting findings.

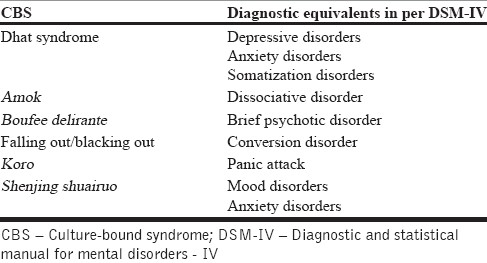

The same argument could be extended to other current CBSs as the cases of functional somatic/functional affective/functional behavioral disorders. This would mean a more systematic study of these conditions that would help in improving the understanding and management of these conditions. Description of the many conditions currently labeled as CBS have diagnostic equivalents in DSM-IV [Table 1].

Table 1.

Manifestations currently labeled as culture bound syndromes and their diagnostic equivalents in DSM IV

CONCLUSIONS

There is a need to reconsider CBSs in the light of the available literature. Relabeling and inclusion of these manifestations in the mainstream diagnostic categories in the upcoming revisions of the diagnostic manual would pave way for a better understanding and management of these conditions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.text rev. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 2.2nd Ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. International statistical classification of diseases and health related problems, (The) ICD-10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wig N. Problems of mental health in India. J Clin Social Psychol (India) 1960;17:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatia MS, Bohra N, Malik SC. ‘Dhat’ syndrome–A useful clinical entity. Indian J Dermatol. 1989;34:32–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumathipala A, Siribaddana SH, Bhugra D. Culture-bound syndromes: The story of dhat syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:200–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.3.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mumford DB. The ‘Dhat syndrome’: A culturally determined symptom of depression? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:163–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jadhav S. Dhat syndrome: A re-evaluation. Psychiatry. 2004;3:14–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raguram R, Jadhav S, Weiss M. Historical perspectives on Dhat syndrome. NIMHANS J. 1994;12:117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trujillo M. Multicultural Aspects of Mental Health. (77-84).Prim Psychiatry. 2008;15:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salmon P, Peters S, Stanley I. Patients’ perceptions of medical explanations for somatisation disorders: Qualitative analysis. Br Med J. 1999;318:372–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7180.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowrick C. Advances in psychiatric treatment in primary care. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2001;7:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morriss R, Gask L, Ronalds C, Downes-Grainger E, Thompson H, Goldberg D. Clinical and patient satisfaction outcomes of a new treatment for somatised mental disorder taught to general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:263–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsella A, Kinzie D, Gordon P. Ethnic variation in the expression of depression. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1973;4:435–58. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinman AM. Neurasthenai and depression: A study of somatisation and culture in China. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1982;6:117–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00051427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford CV. New York: Elsevier; 1983. The somatizing disorder: Illness as a way of life. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gureje O, Simon GE, Ustun TB, Goldberg DP. Somatisation in cross-cultural perspective: A World Health Organisation study in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:989–95. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipowski ZJ. Somatization: The concept and its clinical application. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:1358–68. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.11.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al Busaidi ZQ. The Concept of Somatisation A Cross-cultural perspective. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2010;10:180–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishore RV, Kapoor V, Gill J. Characteristics of mental morbidity in a rural primary health centre of Haryana. Indian J Psychiatry. 1996;38:137–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S, Yu H, Wing Y, Chan C, Lee AM, Lee DT, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and illness experience of primary care patients with chronic fatigue in Hong Kong. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:380–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perme B, Ranjith G, Mohan R, Chandrasekaran R. Dhat [semen loss] syndrome: A functional somatic syndrome of the Indian subcontinent? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:215–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Littlewood R. Cultural comments on culture bound syndromes in culture and psychiatric diagnosis: A DSM–IV Perspective. In: Mezzich J, Kleinman A, Fabrega H, Parron D, editors. Washington, DC: APA; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canino G, Alegrıa M. Psychiatric diagnosis – Is it universal or relative to culture? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;4:237–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinman AM, Good B. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. Introduction: Culture and depression. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirmayer LJ. Culture, affect and somatisation. Transcult Psychiatr Res Rev. 1984;21:159–88. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devins GM. Culturally informed psychosomatic research. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46:519–24. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malhotra HK, Wig NN. Dhat syndrome: A culture bound sex neurosis in the Orient. Arch Sex Behav. 1975;4:519–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01542130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chadda RK. Dhat syndrome: Is it a distinct clinical entity? A study of illness behaviour characteristics. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91:136–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dewaraja R, Sasaki Y. Semen-loss syndrome: A comparison between Sri Lanka and Japan. Am J Psychother. 1991;45:14–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1991.45.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perme B, Ranjith G, Mohan R, Chandrasekaran R. Dhat (semen loss) syndrome: A functional somatic syndrome of the Indian subcontinent? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:215–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marilov VV. Culturally determined Dhat syndrome. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2001;101:42–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]