Abstract

Acamprosate with dual mechanism of action as glutamate antagonist and GABA agonist can be a potential target to decrease the severity of sensorineural tinnitus.

Objective:

(1)To study the effectiveness of acamprosate in providing subjective relief and objective improvement in patients having tinnitus of sensorineural origin. (2) To evaluate the adverse events related to the use of acamprosate and also determine the change in quality of life (QOL) parameters.

Materials and Methods:

The study was randomized double-blind, placebo controlled, crossover. Forty adult subjects (>18 years of age), of either sex with tinnitus of sensorineural origin, were administered either acamprosate 333 mg TDS or matched placebo for a period of six weeks followed by a washout period of one week. Drug therapy was switched for another six weeks in consonance with the crossover design. The effect of acamprosate and placebo on subjective relief and objective improvement was evaluated by using modified tinnitus severity, QOL scores and audiometry with tinnitus matching in frequency and loudness.

Results:

At the end of the study, the drug had shown a statistically significant improvement in reducing the tinnitus score in 92.5% of the patients and placebo with an improvement in 12.5% of the patients. The drug was well tolerated without any serious drug reactions.

Conclusion:

Acamprosate is an effective drug in treating the severity of sensorineural tinnitus without causing much of the side effects.

KEY WORDS: Acamprosate, audiometry, sensorineural tinnitus, tinnitus matching

Introduction

Tinnitus is characterized by the perception of sound or noise in the absence of any internal or external acoustical stimulation.[1] There is increasing evidence that functional changes both in cochlea and central nervous system are involved in the pathophysiology of different types of tinnitus. Increase in the release of glutamate, the major neurotransmitter both in the cochlea and in the central auditory pathways, has been suggested to be involved in the generation and maintenance of sensorineural tinnitus by causing “excitotoxicity” and thus overexpression of NMDA receptors.[2] Therapy for tinnitus is focused on drugs that act directly on CNS neurotransmitters, like glutamate, GABA, serotonin, acetylcholine and dopamine. Glutamate receptor antagonists which block glutamate binding sites and prevent/attenuate the influx of calcium can be useful for the condition.[3] Acamprosate, a drug used for treating alcohol dependence, was first reported as a potential treatment for tinnitus in 2005.[4] The drug acts by a dual mechanism of action, acting both as a glutamate antagonist and as a GABA agonist. A recent double-blind study reported a relief of tinnitus in over 80% of patients treated with acamprosate.[4] The promising application of the drug and multipronged action has prompted to design this study to evaluate the efficacy of acamprosate in subjects who have tinnitus of sensorineural origin.

Materials and Methods

The present randomized, double blind, crossover study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of acamprosate in tinnitus of sensorineural origin.

Primary outcome measures:

To study the effectiveness of acamprosate in providing subjective relief and objective improvement in patients having tinnitus of sensorineural origin.

To determine the changes in quality of life (QOL) parameters over the period of the study.

Secondary outcome measures:

To identify a sub-set of patients of tinnitus in whom acamprosate can be used as pharmacotherapy.

To evaluate the adverse events related to the use of acamprosate.

The protocol for study was submitted to the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) and approval was sought. After getting approval from concerned authorities, 40 subjects were included in the present study.

Drugs to be investigated

Tab. acamprosate 333mg 1 tab TDS for 45 days

Subjects:

Forty adult subjects (>18 years of age), of either sex and suffering from unilateral, bilateral or generalized tinnitus of sensorineural origin, presenting at the Outpatient Department of Ram Lal Eye and Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital and volunteering to participate, were included in this study.

Informed consent was taken from the patient after giving all the aspects of the study.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant and lactating patients were not considered as subjects for the study. Patients with history of serous type of otitis media or otitic barotraumas, conductive or mixed type of hearing loss and those having objective type of tinnitus were excluded from the study. Patients suffering from uni or bi-lateral temporo-mandibular joint disease or the cases taking ototoxic or cytotoxic drugs were also not included in the study.

Type of study

Prospective, randomized, placebo controlled, double-blind, cross over design.

A complete medical history was obtained and recorded on a prescribed performa from all the patients. The patients were allowed to undergo a complete general physical examination and detailed ear, nose and throat examination.

Following tuning fork tests were performed using tuning forks of 256, 512 and 1024 Hz to make a preliminary assessment of type and amount of hearing loss:

Rinne's test using tuning forks of 256, 512 and 1024 Hz.

Weber's test using tuning forks of 512 Hz.

Absolute bone conduction test using tuning fork of 512 Hz.[5]

All the patients were then subjected to pure tone audiometry and tinnitus matching in terms of frequency and loudness using AAA222 inter-acoustic audiometer.[6]

A validated questionnaire was used and filled by assisting the patient to quantify the impact of subjective sensation of tinnitus on patient's ‘quality of life’ (QOL).[7] The scoring system was done to quantify the severity of tinnitus and its impact on QOL. These patients were also subjected to visual analogue scale for loudness in cm along a 10 cm scale.[8]

These patients were provided with acamprosate 333 mg TDS or matched placebo for a period of fifteen days. Follow up was done every fifteen days till the end of the study for filling in the questionnaire, ENT examination and drug collection. They were divided into two groups on the basis of treatment given to them.

Group I: tab.acamprosate 333 mg 1 tab. p.o thrice a day

Group II: matched placebo 1 tab. p.o. thrice a day

This schedule of treatment was continued for forty five days. Afterwards, these patients were subjected to a washout period of seven days and later crossed over to acamprosate or placebo as follows for next forty five days.

Group I: matched placebo 1 tab. p.o thrice a day

Group II: tab. acamprosate 333mg 1 tab. p.o. thrice a day

The effect of the drug was studied both as a subjective and objective improvement in visual analogue score (VAS) or QOL questionnaire score. A decrease in tinnitus loudness was considered as objective improvement. The results were then compiled and analyzed statistically by using Student ‘t’ test for independent samples.

The criterion for determination of significance was 5%, with ‘P’ value of the statistical test smaller or equal to 0.05.

Results

A total of forty five patients were taken. Two patients reported their conditions to be worse and they were shifted to another treatment. Three patients left in between and could not complete the study. Forty patients were able to complete the study. All of them had a varying degree of sensorineural hearing loss. The pure tone audiogram depicted a ‘downward sloping curve’ in these patients. 65% of patients had bilateral hearing loss and 35% had bilateral tinnitus.

The age of patients was 18 to 84 years with an average of 53 years.

The improvement score or reduction in tinnitus score was observed in 92.5% of patients included in this study. At the end of study, only five patients (7.5%) showed no improvement. Twenty-one patients (77.5%) reported improvement below 50%, six patients (15%) reported improvement higher than 50% and five patients (12.5%) reported that their tinnitus had disappeared

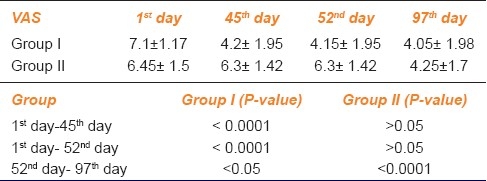

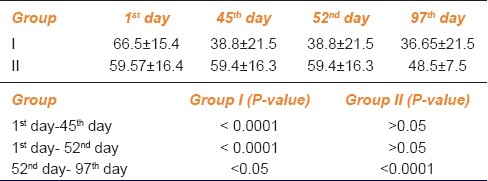

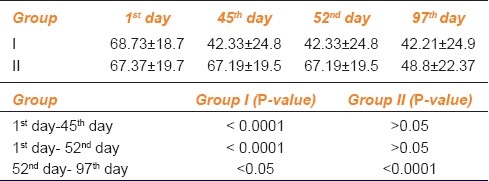

To assess the progression of tinnitus throughout the study period, we had performed the statistical analysis of each study group at first day, 45th day, 52nd day and 97th day in terms of VAS score and QOL questionnaires as shown in AMK Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Visual analogue scale score for loudness of tinnitus

Table 2.

Quality of life score for frequency statement

Table 3.

Quality of life score for severity statement

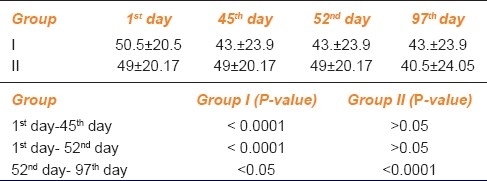

This improvement was also assessed objectively by psychoacoustic reduction in tinnitus matching. 20% did not show any improvement while 80% patients showed improvement in tinnitus loudness. The decrease in tinnitus loudness was varied from 5 dB to zero as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Tinnitus matching for loudness in decibel

In placebo group, 12.5% reported improvement only subjectively. Thus at the end of study, the drug had shown a statistically significant improvement in reducing the tinnitus score in 92.5% of the patients and placebo shown a little improvement in 12.5% of the patients. The subjective improvement was greater than objective improvement. The drug was well tolerated and did not show any serious drug reactions. No patient had any change in audiogram shape. Patients who obtained the best results were those who had the symptoms for shorter duration.

Discussion

Tinnitus is defined as a phantom auditory perception—it is a perception of sound without corresponding acoustic or mechanical correlates in the cochlea.[9] Tinnitus represents one of the most common and distressing otological problems, and it causes various somatic and psychological disorders that interfere with the QOL. Tinnitus is a subjective phenomenon that is difficult to evaluate objectively, with it being measured, quantified, and described only based on the responses of patients.[10]

It has been established that 35–40% of all adults over 17 years of age experience noises lasting longer than 5 min of various degrees of loudness at some time.A miniscule number of patients (0.5%) are in urgent need of treatment. These patients may also experience sleep disorders, poor concentration and depression from which there seems no escape. Another, 0.5-1% of adults report tinnitus of such severity so as to have a significant adverse effect on their QOL.[11]

Current treatments of tinnitus are not cures; they are a means to reduce tinnitus perception or awareness. Well controlled trials of management strategies are few and published success rates of most treatments remain controversial. Despite this, there is sufficient evidence to advocate existing strategies to reduce tinnitus annoyance and improve QOL.

Other drugs already studied for treatment of tinnitus are lidocaine,[12] antidepressants,[13] baclofen,[14] caroverine,[15] nimodipine,[16] clonazepam[17] and trimetazidine.[18] The introduction of these drug therapies have increased the success of tinnitus treatment.

Different studies have shown that sensorineural tinnitus is caused by an imbalance of these two neurotransmitters with an excitatory predominance. There are many drugs that act on neurotransmitters, but only very few modulate the GABA-glutamate system in the afferent auditory pathway and had no major undesirable side effects.[19]

Modulation of glutaminergic transmission by topical administration of the nonselective glutamate receptor antagonist caroverine to the inner ear has been proposed for tinnitus treatment. However, the systemic use of nonselective glutamate receptor blockers such as caroverine is limited by severe neurological and psychiatric side effects.[15]

Gabapentin, a GABA-mimetic, has shown encouraging results in the improvement of tinnitus in high doses.[20] But there is little evidence to support the general use of gabapentin in subjective tinnitus. Acamprosate, a drug used in the treatment of alcohol addiction, could have a similar effect in the auditory afferent pathway. Its dual mechanism of action, which reduces the glutaminergic transmission (excitatory) and increases the GABA activity (inhibitory), together with its excellent tolerability, makes it a promising drug for treatment of tinnitus. There is lack of literature on the use of acamprosate for tinnitus treatment.

The present study has been designed to evaluate the effectiveness of acamprosate in sensorineural tinnitus. This study had also proved the better results to cure the sensorineural tinnitus as compared to placebo. The subjective assessment was done by visual analogue score and QOL questionnaires. The objective improvement was compared with tinnitus matching in frequency and loudness. The improvement rate in drug group was better than placebo. The improvement score was seen in 92.5% of drug treated patients.

The improvement score or reduction in tinnitus score was observed in 92.5% of patients included in this study as compared to previous study which showed an improvement score of 86.9% in 90 days. At the end of study, only five patients (7.5%) showed no improvement as compared to 13.06% in previous study. Twenty-one patients (77.5%) reported improvement below 50%, six patients (15%) reported improvement higher than 50%. Five patients (12.5%) reported that their tinnitus had disappeared as compared to 13.04% in previous study.

Objective improvement was seen in 80% of patients reducing the severity of tinnitus loudness up to 5dB to zero

In placebo group, 12.5% reported improvement subjectively only.

The subjective improvement was greater than objective improvement. The drug was well tolerated and did not show any serious drug reactions. No patient had any change in audiogram shape. Those patients who were fully treated or obtained the best results were those who had the symptoms for less time. On the basis of the findings of this study, it may be concluded that acamprosate is superior to placebo in relieving the symptoms of sensory neural tinnitus. Its safety profile is conducive to long-term uses.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Roedel KL. The Ear Foundation of Arizona Information About Tinnitus: General Information and Prevalence [serial Online] 1992. [Last cited in 2008 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.ata.org/

- 2.Pujola R, Puel JC. Excitotoxicity, synaptic repair, and functional recovery in the mammalian cochlea: A review of recent findings. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;55:249–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillespie DC, Kim G, Kndler K. Inhibitory synapses in the developing auditory system areglutaminergic. Nat Neurosci. 2005;55:332–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azevedo AA, Figueiredo RR. Tinnitus treatment with acamprosate: Double-blind study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71:618–23. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31266-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chartrand MS. Indiana Jones and the Lost of Art of Tuning Fork Testing. [cited in 2008 Oct 16];The Hearing Journal. 2007 Available from: http://www.Audiology Online.com 2007/html . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovrinic JH. Pure Tone and Speech Audiometry. In: Keith RW, editor. Audiology for the Physician. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1980. pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folmer RL, Griest SE. Chronic tinnitus resulting from head or neck injuries. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:821–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200305000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azevedo AA, Oliveira PM, Siqueira AG, Figueiredo RR. A critical analysis of tinnitus measuring methods. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol. 2007;73:418–23. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30088-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jastreboff PJ. Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): Mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci Res. 1990;8:221–54. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(90)90031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han IB, Lee HW, Kim TY, Lim JS, Shin KS. Tinnitus: Characteristics, causes, mechanisms, and treatments. J Clin Neurol. 2009;5:11–9. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2009.5.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heller AJ. Classification and epidemiology of tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003;36:239–48. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(02)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.TayyarKalcioglu M, Bayindir T, Erdem T, Ozturan O. Objective evaluation of the effects of intravenous lidocaine on tinnitus. Hear Res. 2005;199:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson S, Viirre E, Stein M. Antidepressant therapy in tinnitus. Hear Res. 2007;226:221–31. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westerberg BD, Roberson JB, Stach BA. A double-blind placebo controlled trial of baclofen in the treatment of tinnitus. Am J Otol. 1996;17:896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domeisen H, Hotz MA, Hausler R. Caroverine in tinnitus treatment. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998;118:606–8. doi: 10.1080/00016489850154801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies E, Knox E, Donaldson I. The usefulness of nimodipine: An L-calcium channel antagonist, in the treatment of tinnitus. Br J Audiol. 1994;28:125–9. doi: 10.3109/03005369409086559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pech A. A multicenter double blind versus placebos study of trimetazidine in tinnitus: A clinical approach to tinnitus. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 1990;107(Suppl 1):66–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganança MM, Caovilla HH, Ganança FF, Ganança CF, Munhoz MS, Da Silva ML, et al. Clonazepam in the pharmacologic treatment of vertigo and tinnitus. Int Tinnitus J. 2002;8:50–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shulman A, Goldstein B. A final common pathway for tinnitus-Implications for treatment. Int Tinnitus J. 1996;2:137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakhshaee M, Ghasemi M, Azarpazhooh M, Khadivi E, Rezaei S, Shakeri M, et al. Gabapentin effectiveness on the sensation of subjective idiopathic tinnitus: A pilot study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:525–30. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]