Abstract

Bacillus subtilis RecU protein is involved in homologous recombination, DNA repair, and chromosome segregation. Purified RecU binds preferentially to three- and four-strand junctions when compared to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) (≈10- and ≈40-fold lower efficiency, respectively). RecU cleaves mobile four-way junctions but fails to cleave a linear dsDNA with a putative cognate site, a finding consistent with a similar genetic defect observed for genes classified within the ε epistatic group (namely ruvA, recD, and recU). In the presence of Mg2+, RecU also anneals a circular ssDNA and a homologous linear dsDNA with a ssDNA tail and a linear ssDNA and a homologous supercoiled dsDNA substrate. These results suggest that RecU, which cleaves recombination intermediates with high specificity, might also help in their assembly.

Keywords: DNA repair, RuvC, RuvAB, RusA

Cells have evolved several distinct mechanisms to help them maintain the structural and informational fidelity of their DNA and to participate in the reorganization and efficient segregation of sister chromatids. In bacteria, much of our understanding on the molecular mechanisms of those processes has come from exploiting Escherichia coli as a model organism (1–6). However, certain key enzymatic components from the DNA repair and segregation apparatuses of Gram-positive bacteria differ significantly from those found in E. coli. For example, the RecU protein (also termed PrfA; ref. 7) is highly conserved among Gram-positive bacteria but is not present in E. coli cells (8).

In Bacillus subtilis, which is a model organism among Gram-positive and naturally transformable bacteria, the absence of RecU causes increased sensitivity to DNA damaging agents, reduces plasmid transformation, and affects chromosomal segregation (7, 8). Mutations in genes classified within the α (recF, recL, recO, recR, and recN) and ε (recB, recU, and recD) epistatic groups render cells very sensitive to the killing action of DNA-damaging agents, whereas mutations in the β (addA and addB), γ (recH and recP), and ζ (recS) epistatic groups render cells only moderately sensitive (9). The genes classified within the α and β epistatic groups have their counterpart on the E. coli RecF (EcoRecF) and EcoRecBCD pathways, respectively (9–11).

B. subtilis cells growing under defined conditions develop the ability to take up, in a sequence-independent manner, large amounts of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) at the onset of stationary phase (natural competence). In chromosomal transformation, RecA promotes invasion of the donor ssDNA into the single-copy recipient double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and the formation of a three-strand intermediate (12, 13). This intermediate, which resembles a D-loop, is thought to be processed via a three-strand nicking protein that removes the flanking DNA to allow strand integration (13). However, plasmid transformation, provided that there is no homology with recipient DNA, is a RecA-independent process (12, 13) that requires DNA replication and some recombination functions. DNA replication is required for the synthesis of the complementary strand of the internally repeated donor linear ssDNA (12), and RecO, RecU, and RecS, when present in an otherwise Rec+ strain, are required to generate and resolve recombination intermediates into a circular dsDNA molecule (8, 10).

A recU null mutant produces 1–3% anucleate cells and asymmetrically located nucleoids (7). Such a defect increases synergistically on a synthetic conditional ΔrecU Δsmc and additively in a ΔrecU Δspo0J double-null mutant (7). These data suggest an important role not only for SMC and Spo0J but also RecU in chromosomal segregation (7, 14).

In this work, we found that purified RecU binds with high affinity to three- and four-strand structures. In the presence of Mg2+, RecU cleaved a mobile Holliday junction (HJ) in vitro. This finding is consistent with the observation that RecU shares a structural relationship with the PvuII enzyme (15). RecU introduces asymmetrical nicks with a certain sequence specificity but fails to cleave a linear dsDNA or ssDNA substrate containing a cognate site. RecU also forms joint molecules (JMs). The presence of gene product(s) with homology to E. coli junction-resolving enzymes is not obvious in B. subtilis cells free of the SKIN prophage, which encodes for a rusA-like product (16, 17). We propose that in Gram-positive bacteria with a low dC + dG content in their DNA, the RuvAB helicase (see ref. 18) and the RecU HJ-specific endonuclease target the HJ formed from a damaged fork and cleave the junction on opposing strands. The observations that the ruvA gene complements the recB2 mutation (renamed ruvA2 here) and that ruvA and recU belong to the same epistatic group strongly support the hypothesis that both RuvAB and RecU work in a concerted fashion.

Materials and Methods

RecU Protein Purification. E. coli BL21(DE3) [pLysS] cells containing pCB210-borne recU gene (8) were resuspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/1 mM DTT/5% glycerol) containing 100 mM NaCl and lysed with a French press. Polyethyleneimine was added to precipitate the 24-kDa RecU protein and chromosomal DNA. RecU was resuspended in buffer A containing 300 mM NaCl, and the pellet containing chromosomal DNA and other proteins was discarded. RecU was precipitated by addition of solid ammonium sulfate (80% saturation), resuspended in buffer A, and purified by using two different chromatographic steps (phosphocellulose and DNA agarose). FPLC-gel filtration (Superose 12, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was used to separate RecU from a nuclease contaminant. The RecU protein, free of EcoRecA, EcoRecO, EcoRecT, and EcoRuvC proteins, was >99% pure, as judged by 15% SDS/PAGE and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-f light (MALDI-TOF) analysis. The RecU concentration was determined by using a 24,900 M–1·cm–1 molar extinction coefficient and is expressed as mol of protein monomers.

DNA Manipulations. DNA concentration is expressed as mol of nucleotides. Linear 6,065-bp HindIII-MscI-M13mp18 dsDNA, 194-nt and 194-bp EcoRI-FspI-M13mp18 ssDNA and dsDNA and 225-nt (pUC18 coordinates 2442–2667) ssDNA were used (19). Linear M13mp18 dsDNA with 3′ ssDNA termini of ≈140 nt (3′-tailed dsDNA) was prepared as described (19). For the construction of DNA structures combinations of oligos (1–6) were used (20). Annealing of oligos 1–4 and 1–3 gives rise to the fixed four- and three-strand junctions, respectively. Oligos 1 and 4 yield flayed duplex, and oligos 1, 5 and 6 yield Y-junctions. The mobile four-strand junction (Jbm6), which contains a 13-bp mobile core, was constructed by annealing strands a–d (strand a, 5′-GCGTTACAATGGAAACTATTCTTGGCAGTTGCATCCAACG-3′; strand b, 5′-CGTTGGATGCAACTGCCAAGAATAGTGTCAGTTCCAGACG-3′; strand c, 5′-CGTCTGGAACTGACACTATTCTTGGCAAATGGTCGTAAGC-3′; and strand d, 5′-GCTTACGACCATTTGCCAAGAATAGTTTCCATTGTAACGC-3′). The sequence of the mobile Jbm5 junction, which contains a 12-bp mobile core, has been described (21). In all constructs, one of the oligos was γ-32P end-labeled, and after annealing the products were gel purified.

The γ-32P 194-nt (0.3 μM) or α-32P 194-bp fragments (0.3 μM) were used to analyze the binding of RecU to DNA through electrophoretic mobility-shift assays (EMSA) in buffer B (25 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/1 mM DTT/50 mM NaCl/50 μg/ml BSA/5% glycerol) containing the indicated amounts of MgCl2. The reactions were stopped and separated in a 6% nondenaturing (nd) PAGE, and the gels were dried before autoradiography.

The 6,065-bp 3′-tailed dsDNA or blunt-ended dsDNA (60 μM) and homologous circular M13mp18 ssDNA (30 μM) were incubated with RecU (250 nM) in buffer B containing the indicated amounts of MgCl2 or ATP for 30 min at 37°C. The samples were deproteinized as described (19) and fractionated through 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) with ethidium bromide (EtdBr).

A homologous γ-32P 194-nt (0.4 μM) or nonhomologous γ-32P 225-nt ssDNA (0.4 μM) and supercoiled M13mp18 dsDNA (30 μM) were incubated with increasing amounts of RecU in buffer B containing 1 mM MgCl2 at 37°C for 30 min. The samples were deproteinized (19) and fractionated by 0.8% AGE with EtdBr (to localize supercoiled DNA), and the gels were dried and analyzed by autoradiography. The signal was quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Cleavage of the labeled Jbm6 and Jbm5 substrate (0.3 μM) by RecU was assayed at 37°C in buffer B containing 10 mM MgCl2. Reactions (10 μl) were stopped by the addition of 50 mM EDTA and heating at 80°C for 5 min. Reaction products were analyzed by using 15% denaturing PAGE.

Electron Microscopy Analysis. The reactions containing 3′-tailed dsDNA (60 μM) and homologous circular M13mp18 ssDNA (30 μM) were incubated with various amounts of RecU for 60 min at 37°C in buffer B containing 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.01% Triton. DNA·protein complexes were visualized by mica adsorption, and for visualization of JMs, the samples were deproteinized (19) and cytochrome c spreading in the presence of 50% formamide and carbonate buffer on a water hypophase was used (22).

Results

Purification and Physical Properties of RecU. B. subtilis RecU protein was expressed in E. coli cells and purified to 99% homogeneity as assayed by SDS/PAGE, MALDI-TOF MS, and quantitative analysis of the N-terminal amino acid sequence (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). RecU consists of a 206-residue polypeptide with a molecular mass of 23,958 Da (8). This finding was in good agreement with the molecular mass of RecU protein as determined by MALDITOF MS (23,945 Da) and by size fractionation through a gel-filtration column (≈25 kDa) in the absence of Mg2+ and in the presence of 1 M NaCl (23).

RecU Binds DNA. RecU was assayed for its ability to act as dsDNA or ssDNA nuclease (exo- or endonuclease), to hydrolyze ATP in the presence or absence of ssDNA or dsDNA, to unwind DNA, and to bind to ssDNA or dsDNA. We observed that RecU binds DNA.

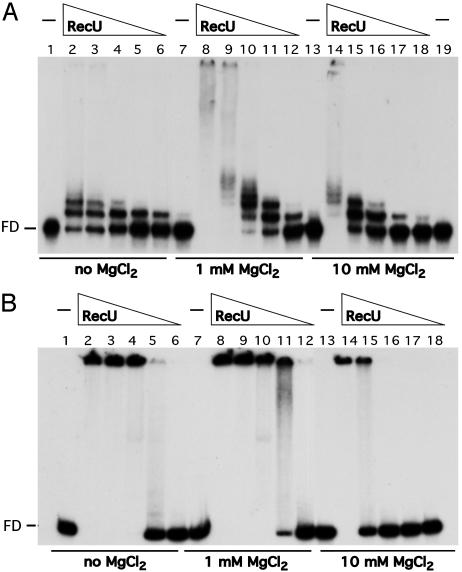

RecU does not seem to form stable complexes with 50-nt or 50-bp DNA (see below). To learn about the type of complexes formed by RecU on DNA and the effect of Mg2+, a γ-32P 194-nt ssDNA or a α-32P 194-bp dsDNA fragment was incubated with increasing concentrations of RecU in the presence or the absence of Mg2+, and EMSA was performed. In the absence of Mg2+, the protein concentration to reach the midpoint of RecU·ssDNA and RecU·dsDNA complex formation (Kapp) was similar, ≈35 and ≈60 nM, respectively. At low protein concentrations, discrete RecU·ssDNA complexes were observed, whereas with dsDNA, high-molecular-weight RecU·dsDNA complexes that did not enter the gel were observed (Fig. 1, lanes 2–6). In the presence of low (1 mM) and high (10 mM) MgCl2 concentrations the types of RecU·DNA complexes were very similar (Fig. 1, lanes 7–19). The affinity of RecU for the DNA was modulated by the MgCl2 concentration. The RecU concentration midpoint with ssDNA was 10 and 37 nM and with dsDNA was 30 and 130 nM, in the presence of 1 or 10 mM MgCl2, respectively.

Fig. 1.

RecU binds ssDNA and dsDNA. A 194-nt γ-32P ssDNA (A) or 194-bp α-32P dsDNA (B) (0.3 μM) was incubated with various amounts of RecU (150 to 9 nM in lanes 2–6, 8–12, and 14–18 of A, and 300 to 18 nM in lanes 6–2, 8–12, and 14–18 of B) in buffer B containing no MgCl2 or the indicated amounts of MgCl2 at 37°C for 15 min. The protein·DNA complexes formed were analyzed by using EMSA. FD, free DNA; –, absence of RecU.

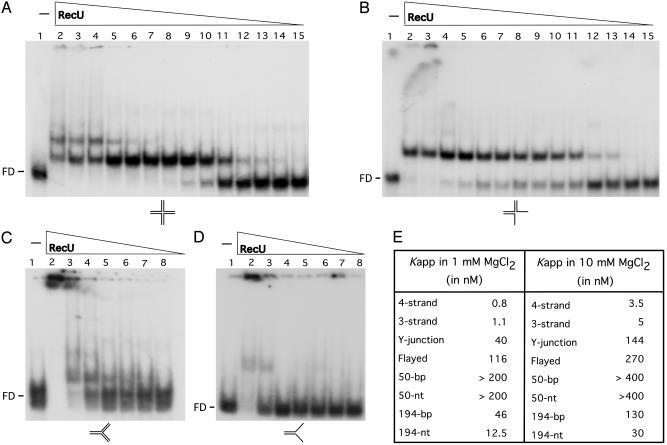

RecU Specifically Binds to Three- and Four-Way Junctions. Binding of RecU to various DNA structures and to 50-nt and 50-bp DNA was assayed. As revealed in Fig. 2E, in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2, RecU binds with poor affinity to 50-nt or 50-bp DNA. The Kapp of RecU·4- and RecU·3-strand complexes was ≈40- and ≈100-fold lower than the RecU concentration needed to reach half-saturation with the Y-junctions and flayed structures. Two and one high affinity retarded species were observed with the four- and three-strand substrates, respectively. When the Y-junction substrate was tested, one retarded species was observed at low RecU, but high-molecular-weight species were observed with both Y-junction and flayed substrates (Fig. 2 A–D). In the presence of 10 mM MgCl2, a 2- to 4-fold higher RecU concentration was required to reach half-saturation when compared to low Mg2+ (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

DNA-binding specificity of RecU. EMSA showing binding of RecU to the indicated γ-32P DNA substrates (four- and three-way, Y-junction, and flayed; A–D, respectively). Binding reactions contained 0.3 μM DNA species and increasing amounts of RecU protein (from 400 to 0.05 in lanes 2–15 of A and B, and 400 to 6.2 in lanes 2–8 of C and D) in buffer B containing 1 mM MgCl2.(E) The RecU concentration to reach half-saturation (Kapp) with the different DNA substrates used at the MgCl2 concentrations indicated. The values are the average of three independent experiments.

When the experiments described in Fig. 2 A were performed in the presence of a 20-fold excess of competitor ssDNA (M13 mp18 ssDNA), no RecU·4-strand complexes were observed. Similar results are observed when the RecU·4-strand complexes were challenged with a 50-fold excess of linear or supercoiled M13mp18 competitor dsDNA (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This finding is consistent with the Kapp values obtained in the previous experiments and suggests that RecU has a specificity for three- and four-strand structures that are key intermediates in homologous recombination.

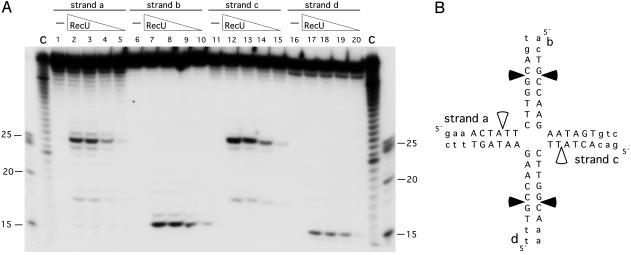

RecU Cleaves Mobile Four-Way Junctions at Discrete Sites. We failed to detect RecU endonuclease activity when using linear or supercoiled pUC18 DNA or the fixed four-strand junction used in Fig. 2 A. A four-strand junction, containing a 13-bp mobile core (Jbm6), was then used to address whether RecU cleaves this junction. RecU introduced discrete symmetric nicks on the Jbm6 substrate. In the a and c strands, a major nick site at the 5′-TGG↓CAg-3′ and 5′-TGG↓CAa-3′ sequences and a minor one at 5′-CTA↓TTC-3′ were observed (Fig. 3). In the b and d strands, the nicks were at the 5′-cTG↓CCA-3′ and 5′-tTG↓CCA-3′ sequences.

Fig. 3.

Determination of the cleavage sites produced by RecU. (A) Four-strand junction Jbm6, γ-32P-labeled at the indicated strand, was incubated with increasing amounts of RecU (100 to 12.5 nM in lanes 2–5, 7–10, 12–15, and 17–20) in buffer B containing 10 mM MgCl2 at 37°C for 30 min. Reaction products were analyzed by using 15% denaturing PAGE. The γ-32P-labeled markers are degraded 40 (C), 25, 20 and 15 nt. (B) The sequence of the 13-bp mobile core is shown in capital letters, and the nonmobile part of the junction is shown in lowercase letters. Major nicking sites are denoted by filled arrows, and minor nicking sites are denoted by open arrows.

The major nick at strand a corresponded with a cleavage site obtained in strand b (Fig. 3B). We ruled out that RecU introduces a double-strand break because after deproteinization and separation with 15% nondenaturing PAGE, a 40-bp nicked product accumulated, but a 15-bp duplex was not detected (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). It is likely, therefore, that the cleavage products observed under denaturing PAGE correspond to symmetric nicks, one on strands a and c and the other on b and d, rather than a double-strand break. The single-strand nicks are consistent with the observations that (i) the RecU cleavage products have ligatable ends (ref. 15 and data not shown) and (ii) RecU failed to cleave a 40-bp dsDNA segment or a supercoiled plasmid DNA containing the 5′-TGG↓CAg-3′ sequence.

When a four-way junction substrate containing a 12-bp mobile core (Jbm5) was used (see ref. 21), the major cleavage in strand a at position 5′-TGG↓Cag-3′ accumulates, but the corresponding nick at strand c (which now has the sequence 5′-TGGCga-3′) was not observed (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These results allow us to conclude that the RecU promoted nicks can be uncoupled and that the second position at the 3′ end of the nicking side might be relevant.

From the results obtained with Jbm6, we cannot derive a consensus cleavage site, but a certain preference for the 5′-G/TG↓CA/C-3′ sequence could be predicted. This sequence appears to be distinct from the cognate sites of E. coli RuvC and RusA resolvases, which preferentially recognize structures containing the symmetrically related 5′-TT↓G/C-3′ and 5′-↓CC-3′ dinucleotide pairs, respectively (24). The absence of cleavage at 5′-TT↓G/C-3′ or 5′-↓CC-3′ is consistent with the observation that our RecU preparations are free of EcoRuvC and EcoRusA (see Materials and Methods).

B. subtilis ruvA and ruvB Mutants Map in the recB2 Region. Previously it was shown that the activity of the ε epistatic group requires the recB, recD, and recU gene products (25), but the recD and recB gene products have yet to be identified. B. subtilis lacks an identifiable homolog of EcoRuvC despite the presence of the RuvAB branch migration complex (16, 17). If RecU is a HJ resolvase, we can predict that the ruvA and ruvB genes might map in the recB and/or the recD regions.

The recB2 and recD41 strains fail to form colonies in the presence of 40 μg/ml methyl methane sulfonate (MMS) (Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Three PCR products, which amplified the ruvA ruvB, ruvA, and ruvB genes, were used to transform recB2 and recD41 cells with selection for MMS resistance. Transformed recB2 cells with the ruvA ruvB DNA are resistant up to 400 μg/ml MMS, but transformed recD41 cells failed to form colonies in the presence of 40 μg/ml MMS. DNA of the ruvA region transformed recB2 cells to MMS resistance, but DNA from the ruvB region failed to do so. It is likely, therefore, that genes coding for the multifunctional RuvAB helicase map in the recB2 region. The recB2 mutant was renamed ruvA2.

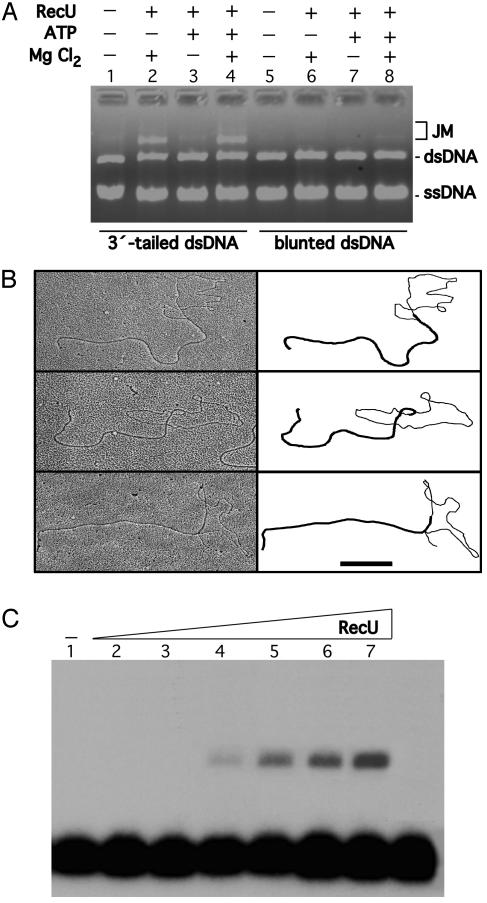

RecU Promotes Annealing Between Circular ssDNA and Homologous 3′-Tailed Linear dsDNA. RecU binds to ssDNA and dsDNA and promotes the formation of high-molecular-weight complexes. To learn whether the high-molecular-weight material correspond to DNA·DNA complexes, the protein was incubated with circular ssDNA and homologous linear dsDNA, the reaction was deproteinized, and the DNA molecules were separated by 0.8% AGE. Formation of JM was not observed when RecU was incubated with circular ssDNA and linear blunt-ended dsDNA (Fig. 4A, lanes 5–8). RecU promoted, however, the accumulation of JMs between linear 3′-tailed dsDNA and a homologous circular ssDNA in the presence of Mg2+ but in the presence or absence of a nucleotide cofactor (Fig. 4A, lanes 1–4, and data not shown). JM increased linearly with increasing concentrations of RecU up to a maximum of ≈30% of total dsDNA substrate. Thus, the reaction is ≈60% efficient because only ≈50% of the dsDNA substrate has a 3′-end ssDNA tail of ≈140 nt (see Materials and Methods). Furthermore, titration with MgCl2 showed an optimum for JM formation between 0.25 to 2.5 mM.

Fig. 4.

Formation of JMs promoted by RecU. The strand exchange reaction mixtures contained RecU (250 nM), circular M13mp18 ssDNA (30 μM), and M13mp18 linear dsDNA (60 μM) in buffer B in the presence or absence of 1 mM MgCl2 or 2 mM ATP (A). The linear 3′-tailed (A, lanes 1–4, and B) and blunt-ended dsDNA substrate (A, lanes 5–8) were used. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min, and the deproteinized products were analyzed by using 0.8% AGE (A). + and –, Presence of absence of the indicated product. (B) RecU (250 nM), circular M13mp18 ssDNA (28 μM), and M13mp18 linear 3′-tailed dsDNA (28 μM) in buffer B in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min, and the deproteinized products were analyzed by using electron microscopy. A gallery of partially dsDNA circles with a dsDNA and ssDNA branch attached to the circle is indicated. A schematic representation of the branch of dsDNA and ssDNA is denoted. (Scale bar, 0.5 μm.) (C) A homologous 194-nt γ-32P ssDNA (0.4 μM) was incubated with supercoiled RF M13mp18 DNA (30 μM) and various concentrations of RecU (4–125 nM in lanes 2–7) in buffer B containing 1 mM MgCl2 at 37°C for 30 min. The deproteinized products were analyzed by using 0.8% AGE.

In the absence of ATP, RecU failed to promote JM formation between ssDNA and homologous blunt-ended linear dsDNA, but it does when the latter is replaced by linear 3′-tailed dsDNA. It is likely, therefore, that RecU is free of contaminating enzymes capable of generating the 3′-tailed dsDNA (e.g., exonucleases and/or DNA helicases).

To gain insight into the reaction promoted by RecU, the protein was incubated with circular ssDNA and homologous 3′-tailed linear dsDNA. Half of the reaction was deproteinized and both aliquots were examined by electron microscopy. Unlike bona fide ATP-independent strand exchange proteins that form nucleoprotein filaments, rings, or both (e.g., EcoRecT; ref. 10), RecU·ssDNA aggregates bound to the tails of the linear DNA or to the circular ssDNA were observed when the samples were directly absorbed to mica (data not shown). This finding is consistent with the observation that purified RecU is free of EcoRecA, EcoRecT, and EcoRecO (see Materials and Methods).

In the presence of low RecU (125 nM), complexes formed between the 3′ tail of the linear duplex, and the circular ssDNA molecule gave rise to a sigma-shaped structure. A gallery of the images obtained at 250 nM RecU is shown in Fig. 4B. Here, sigma-shaped and, in few cases, structures in which one of the DNA strands of the linear duplex DNA had been displaced by the circular ssDNA (alpha-shaped structures) were observed (Fig. 4B). The short displaced strand is of ssDNA nature, and a stretch of dsDNA of roughly comparable length has been formed on the circular ssDNA molecule. Under the conditions used, the base pairing and heteroduplex extension of the linear 3′-tailed DNA with the circular ssDNA did not exceed ≈1,000 nt, and end products of the strand exchange reaction (nicked circular dsDNA and linear ssDNA) were not observed (data not shown).

RecU Promotes Annealing of a Linear ssDNA with a Homologous Supercoiled Substrate. To further characterize the RecU catalyzed annealing reaction, we analyzed whether RecU promotes assimilation of a 194-nt γ-32P ssDNA segment into homologous supercoiled acceptor DNA, presumably leading to the formation of a D-loop, measured as the comigration of radioactivity with the supercoiled DNA (Fig. 4C). This reaction did not require a nucleotide cofactor because the D-loop was observed in the absence of ATP. Strand assimilation was also observed whether RecU was first incubated with the homologous ssDNA or both ssDNA and supercoiled substrate were added simultaneously.

Under the experimental conditions used, D-loop formation was not observed when (i) RecU was replaced by BSA, (ii)2mM EDTA was added, or (iii) supercoiled DNA was replaced by relaxed dsDNA (data not shown). The amount of JM formed in three independent experiments increased linearly with increasing RecU concentration up to a maximum of ≈12% (Fig. 4C). Formation of JM was not observed (<0.5%) when the heterologous 225-nt γ-32P ssDNA was used (data not shown).

Discussion

The results presented here underpin the significant biological function of RecU in DNA repair, plasmid transformation, and chromosomal segregation. The biochemical analysis performed with purified RecU reveals that, at low Mg2+ concentrations, the protein binds to three and four strands with ≈12- and 46-fold higher affinity than to an ≈200-nt or 200-bp DNA, and with >50-fold higher affinity than to flayed, Y-junction, 50-nt and 50-bp DNA substrates. At high Mg2+ concentrations, RecU introduced specific cuts on mobile four-strand substrates. The protein, however, failed to introduce a nick or a double-strand break on a linear dsDNA having the cognate site. The poor activity of RecU can be rationalized in terms of the sequence specificity of the protein. At present, the extent of the recognition site and the level of degeneracy tolerated are unclear, but replacement of 5′-GG↓Ca-3 for the 5′-GG↓Cg-3 sequence drastically affects its utilization. As described for other HJ-specific resolvases (26), no RecU cleavage was observed with static junctions, although the affinity of the protein to mobile and nonmobile junctions was similar. Because the mobile junctions used are inappropriate to address whether RecU cleaves D-loop structures, the role of RecU in D-loop processing remains open.

Genetic evidence suggests that three-strand recombination intermediates, which resemble a D-loop that cannot be extended to a HJ because of lack of a complementary strand, are formed during chromosomal transformation (see refs. 12 and 13). Because recU-null mutants are highly impaired in DNA repair and plasmid transformation but only marginally impaired in chromosomal transformation in both SKIN-free and SKIN-containing backgrounds, we assume that in wild-type cells, RecU has a minimal role in the processing of D-loops intermediates and a central role in the processing of HJ intermediates that are formed during plasmid transformation and DNA repair (12) or by replication fork regression (1–5). Furthermore, the SKIN-encoded RecT and RusA proteins (16, 17) are either not expressed under normal growth conditions or have different activities than those associated with RecU.

The EcoRuvC resolvase, in concerted action with the EcoRuvAB helicase, targets the HJs and cleaves the junction on opposite strands (1–6, 27). A search for a B. subtilis homolog to EcoRuvC has yielded no matches, whereas genes homologous to EcoRecG, EcoRuvA, and EcoRuvB proteins have been predicted (16). Genetic evidence suggested that RecU works in concert with the RecB and RecD proteins (8, 25). In this paper, we have mapped the B. subtilis ruvA gene to the recB2 region and renamed the latter ruvA2. Both the ΔrecU and ruvA2 mutants show identical segregation defects in cells growing under normal conditions, and these defects are suppressed by a ΔrecA mutation (unpublished results). This finding is consistent with the observation that EcorecA mutants suppress the segregation defects observed with UV-irradiated EcoruvC mutants (28).

RecU was able to bind ssDNA with only ≈12-fold lower affinity than to three- and four-strand recombination intermediates. Furthermore, RecU was able to bind dsDNA as EcoRusA, whereas EcoRuvC binds with high specificity to HJs (29). RecU mediated ssDNA annealing between a linear dsDNA containing a 3′ ssDNA tail and its complementary ssDNA circle. Such annealing activity was not reported for EcoRuvC and EcoRusA proteins. RecU also promoted ssDNA assimilation into a supercoiled substrate (≈12%; Fig. 4C). Although its ability is comparable to that achieved by bacterial EcoRecT and eukaryotic Rad51, XRCC2·Rad51D, and XRCC3·Rad51C protein complexes (30–32), it is ≈3-fold lower when compared to the RecA protein (≈35%) (data not shown). A mediator role has been suggested for the Rad51 paralogs: the Rad51B·Rad51C complex promotes the DNA exchange activity of Rad51 (33). Recently, it has been shown that Rad51C has a DNA strand exchange activity (34), and Rad51B preferentially binds to four-strand junctions (35). A potential role of the human Rad51B·Rad51C complex in the processing of HJ remains, however, to be elucidated.

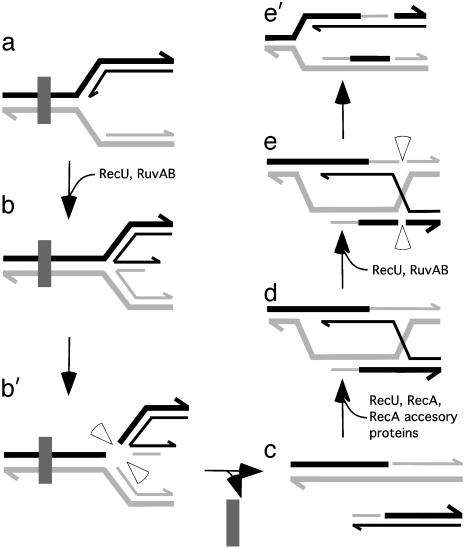

Based on previous results (1–6, 14) and on the results presented here, we hypothesize that when the replisome, at the replication factory, encounters an unrepaired DNA lesion in the template DNA, replication halts. The models for restarting DNA replication repair involve the formation and subsequent resolution of a single or double HJ (1–6). In one of those models, RuvAB, in concert with RecU, targets the HJ formed at the damaged fork and cleaves the junction on opposite strands (ref. 6; Fig. 5 a–b′). RecU acting at the resultant free ends can help RecA to form a D-loop or form D-loops in its own. RuvAB targeted to the junction site promotes branch migration, and RecU resolves the junctions (Fig. 5 d–e′). The symmetrical nicks are sealed by DNA ligase, and the replisome can be reconstituted (1–6).

Fig. 5.

Processing of a HJ at a stalled replication fork by RuvAB and RecU. The fork was halted at a lesion (filled rectangle) within the template DNA (a) (1–6). RuvAB and RecU form a four-stranded HJ (b). RecU introduces symmetrically related nicks to release a free duplex DNA end (b′). The lesion is removed (c). A free DNA end can be recombined with a homologous duplex to create a D-loop (d). RuvAB targeted to the junction site promotes branch migration and RecU resolves the junction (e and e′) (1–6). The RecU cleavage in two of the four strands of the HJ restores a competent replication fork (e′). Half arrows on the DNA strands denote 3′ ends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Camafeita and G. Lüder for excellent technical support and R. D. Camerini-Otero for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was partially supported by Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica Grants BMC2003-00150 and BCM2003-01969 (to J.C.A. and S.A.). S.A. is supported by the Ramón y Cajal Program.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: AGE, agarose gel electrophoresis; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; EtdBr, ethidium bromide; HJ, Holliday junction; JM, joint molecule; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA.

References

- 1.Kowalczykowski, S. C. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michel, B. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox, M. M., Goodman, M. F., Kreuzer, K. N., Sherratt, D. J., Sandler, S. J. & Marians, K. J. (2000) Nature 404, 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGlynn, P. & Lloyd, R. G. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGlynn, P. & Lloyd, R. G. (2002) Trends Genet. 18, 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West, S. C. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen, L. B. & Setlow, P. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 1650–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández, S., Sorokin, A. & Alonso, J. C. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 3405–3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández, S., Ayora, S. & Alonso, J. C. (2000) Res. Microbiol. 151, 481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández, S., Kobayashi, Y., Ogasawara, N. & Alonso, J. C. (1999) Mol. Gen. Genet. 261, 567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chédin, F., Ehrlich, S. D. & Kowalczykowsky, S. C. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 298, 7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacks, S. A. (1988) in Genetic Recombination, eds. Kucherlapati, R. & Smith, G. R. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), pp. 43–86.

- 13.Dubnau, D. (1999) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53, 217–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemon, K. P. & Grossman, A. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 2031–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigden, D. J., Setlow, P., Setlow, B., Bagyan, I., Stein, R. A. & Jedrzejas, M. J. (2002) Protein Sci. 11, 2370–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunst, F., Ogasawara, N., Moszer, I., Albertini, A. M., Alloni, G., Azevedo, V., Bertero, M. G., Bessieres, P., Bolotin, A., Borchert, S., et al. (1997) Nature 390, 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharples, G. J. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 39, 823–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.West, S. C. (1997) Annu. Rev. Genet. 31, 213–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayora, S., Missich, R., Mesa, P., Lurz, R., Yang, X., Egelman, E. H. & Alonso, J. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35969–35979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayora, S., Rojo, F., Ogasawara, N., Nakai, S. & Alonso, J. C. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 256, 301–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kvaratskhelia, M. & White, M. F. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 297, 923–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiess, E. & Lurz, R. (1988) Methods Microbiol. 20, 293–323. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly, S. J., Stein, R. A., Bagyan, I., Setlow, P. & Jedrzejas, M. J. (2000) J. Struct. Biol. 131, 90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolt, E. L. & Lloyd, G. (2002) Mol. Cell 10, 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carrasco, B., Fernández, S., Asai, K., Ogasawara, N. & Alonso, J. C. (2002) Mol. Genet. Genomics 266, 899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lilley, D. M. J. & White, M. F. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Gool, A. J., Hajibagheri, N. M. A., Stasiak, A. & West, S. C. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1861–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishioka, K., Fukuoh, A., Iwasaki, H., Nakata, A. & Shinagawa, H. (1998) Genes Cell 3, 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan, S. N., Vincent, S. D. & Lloyd, R. G. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 1560–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazin, A. V., Zaitseva, E., Sung, P. & Kowalczykowski, S. C. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1148–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurumizaka, H., Ikawa, S., Nakada, M., Eda, K., Kagawa, W., Takata, M., Takeda, S., Yokoyama, S. & Shibata, T. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5538–5543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurumizaka, H., Ikawa, S., Nakada, M., Enomoto, R., Kagawa, W., Kinebuchi, T., Yamazoe, M., Yokoyama, S. & Shibata, T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14315–14320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sigurdsson, S., van Komen, S., Bussen, W., Schild, D., Albala, J. S. & Sung, P. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 3308–3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lio, Y.-C., Mazin, A. V., Kowalczykowski, S. C. & Chen, D. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2469–2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yokoyama, H., Kurumizaka, H., Ikawa, S., Yokoyama, S. & Shibata, T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2767–2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.