Abstract

Cadmium (Cd) is toxic to plant cells. Under Cd exposure, the plant displayed leaf chlorosis, which is a typical symptom of iron (Fe) deficiency. Interactions of Cd with Fe have been reported. However, the molecular mechanisms of Cd-Fe interactions are not well understood. Here, we showed that FER-like Deficiency Induced Transcripition Factor (FIT), AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39, three basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors involved in Fe homeostasis in plants, also play important roles in Cd tolerance. The gene expression analysis showed that the expression of FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 was up-regulated in the roots of plants treated with Cd. The plants overexpressing AtbHLH39 and double-overexpressing FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39 exhibited more tolerance to Cd exposure than wild type, whereas no Cd tolerance was observed in plants overexpressing either AtbHLH38 or FIT. Further analysis revealed that co-overexpression of FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 constitutively activated the expression of Heavy Metal Associated3 (HMA3), Metal Tolerance Protein3 (MTP3), Iron Regulated Transporter2 (IRT2), and Iron Regulated Gene2 (IREG2), which are involved in the heavy metal detoxification in Arabidopsis (Arabidopis thaliana). Moreover, co-overexpression of FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 also enhanced the expression of NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHETASE1 (NAS1) and NAS2, resulting in the accumulation of nicotiananamine, a crucial chelator for Fe transportation and homeostasis. Finally, we showed that maintaining high Fe content in shoots under Cd exposure could alleviate the Cd toxicity. Our results provide new insight to understand the molecular mechanisms of Cd tolerance in plants.

Cadmium (Cd) is a toxic element to plants, animals, and humans. With increased Cd concentrations in agricultural soils due to human activities, such as application of phosphate fertilizer, sewage sludge, wastewater, and pesticide, Cd pollution has become a serious problem for human health. Under Cd exposure, plants displayed chlorosis in young leaves, decreased root growth, and finally died (Kahle, 1993; Das et al., 1997). Plants have evolved several mechanisms for Cd detoxification, which include cell wall binding, chelation with phytochelatins, compartmentation in vacuole, and enrichment in leaf trichomes (Clemens, 2006).

Cd toxicity can be attributed to the competition of metal-binding molecules with other essential metals, especially iron (Fe; Schützendübel and Polle, 2002). Cd enters plant cells through Fe, calcium, and zinc (Zn) transporters/channels (Clemens, 2006). The major Fe transporter, IRT1, of the strategy I plants can transport Cd ions from soil into root cells (Cohen et al., 1998; Lombi et al., 2002; Vert et al., 2002; Yoshihara et al., 2006). Previous studies gave conflicting results regarding the impact of Cd on IRT1 expression and Fe content in roots. Lombi et al. (2002) and Yoshihara et al. (2006) showed that Cd mediated IRT1 expression, whereas Connolly et al. (2002) and Besson-Bard et al. (2009) reported an inhibition of IRT1 expression by Cd. Although the results were inconsistent, they consistently showed that Cd exposure provoked Fe deficiency. However, the molecular mechanism of the Cd-Fe interaction is still not explored.

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) FER is a first cloned regulatory gene involved in Fe uptake in higher plants (Ling et al., 2002). FIT, a functional ortholog of FER in Arabidopsis (Arabidopis thaliana), was also confirmed to be involved in the regulation of Fe uptake from soil under Fe deficiency (Colangelo and Guerinot, 2004; Jakoby et al., 2004; Yuan et al., 2005). Additionally, AtbHLH38, AtbHLH39, AtbHLH100, and AtbHLH101, belonging to the bHLH Ib subgroup of the Arabidopsis bHLH family, displayed an upregulated expression in roots and leaves under Fe deficiency (Wang et al., 2007; Yuan et al., 2008). Further analysis indicated that AtbHLH38 and AtbHLH39 interacted with FIT to form heterodimers FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39, directly activating the transcription of the ferric chelate reductase FRO2 and ferrous transporter IRT1, which are two major genes involved in Fe uptake under Fe deficiency (Eide et al., 1996; Robinson et al., 1999; Henriques et al., 2002; Varotto et al., 2002; Vert et al., 2002; Yuan et al., 2008). IRT1, an essential ferrous transporter in Arabidopsis, has a broad substrate. Besides Fe, it can take up Zn, Mn, Co, Ni, and Cd, leading to accumulation of these metals under Fe starvation (Welch et al., 1993; Rodecap et al., 1994; Yi and Guerinot., 1996; Cohen et al., 1998; Vert et al., 2002; Schaaf et al., 2006). To keep the metal balance and detoxify heavy metals in cells, plants will up-regulate the expression of some genes related to sequestration and chelation of heavy metals. HMA3 (Heavy Metal Associated3), HMA4, MTP1 (Metal Tolerance Protein1), MTP3, and Iron Regulated Gene2 that are related to the Cd, Zn, and Ni sequestration in vacuoles were activated under Fe deficiency (Arrivault et al., 2006; Schaaf et al., 2006; Morel et al., 2009). The Iron Regulated Transporter2 (IRT2) gene that functions in compartmentalization of Fe into vesicles was also up-regulated under Fe deficiency to prevent toxicity of free excess Fe in cytosol (Vert et al., 2009). The expression of NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHETASE1 (NAS1) and NAS2, two nicotianamine (NA) synthetase genes responsible for synthesis of NA in Arabidopsis, were up-regulated under Fe-starved conditions to enhance the translocation of Fe from root to shoot (Kim et al., 2005; Klatte et al., 2009).

In this study, we investigated the functions of bHLH transcription factors FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 in Cd tolerance in Arabidopsis. We demonstrated that FIT interacted with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 to form heterodimers FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39, which can directly or indirectly confer the transcription activation of HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, IRT2, NAS1, and NAS2, resulting in the plants double-overexpressing FIT/AtbHLH38 or FIT/AtbHLH39 more tolerant to Cd.

RESULTS

Cd Exposure Up-regulated the Expression of FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 and Plants Co-overexpressing FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 Exhibited Tolerance to Cd

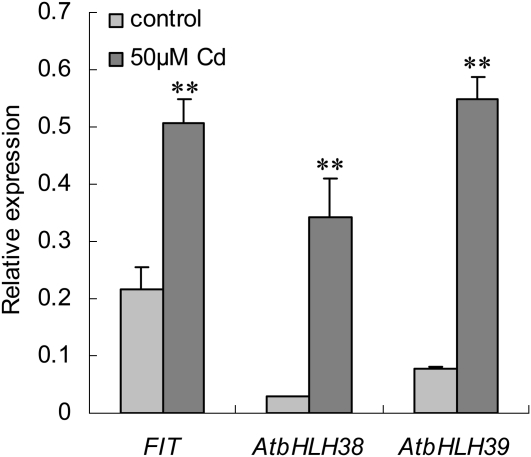

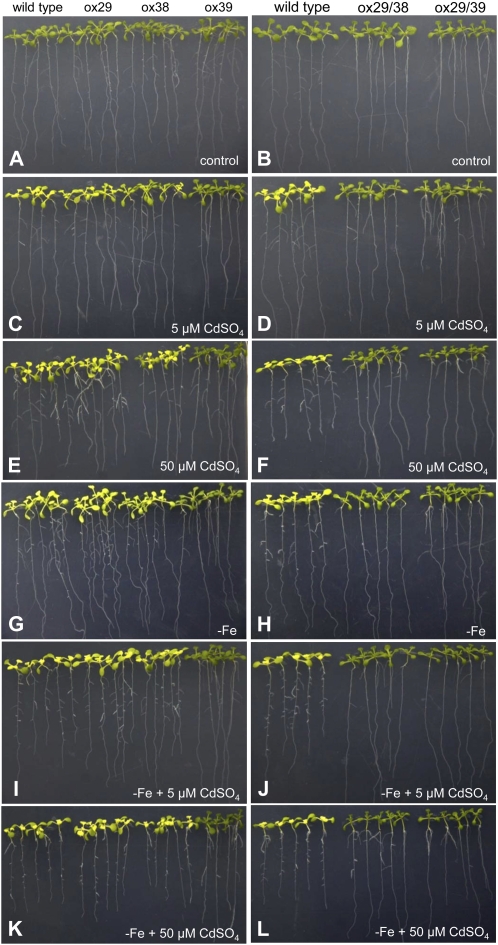

As shown in Figure 1, the expression of FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 was clearly up-regulated in the roots of Arabidopsis seedlings when treated with 50 μm CdSO4. To test whether FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 are involved in Cd tolerance, transgenic plants ox29 (overexpressing FIT), ox38 (overexpressing AtbHLH38), ox39 (overexpressing AtbHLH39), ox29/38 (overexpressing FIT and AtbHLH38), and ox29/39 (overexpressing FIT and AtbHLH39) generated by Yuan et al. (2008) were analyzed. After germination on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog plates for 7 d, the seedlings of homozygous T3 lines of ox29, ox38, ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39 together with wild type were transferred onto one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates without (as control) and with 5 and 50 μm CdSO4 supply. All transgenic lines (ox29, ox38, ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39) and wild type displayed similar growth on the control medium (Fig. 2, A and B). On Cd-containing media, ox29, ox38, and wild type exhibited chlorosis, whereas ox39, ox29/39, and ox29/38 showed normal growth, even on the medium with 50 μm CdSO4 (Fig. 2, C–F). Additionally, the lines ox29/38 and ox29/39 revealed longer root growth than that of wild type (Fig. 2F). Considering that FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 are involved in regulation of Fe uptake, we then tested the Cd tolerance of the transgenic lines on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar media with 5 and 50 μm CdSO4 under Fe deficiency (without Fe supply). Consistent with the results observed on medium with Fe, the transgenic lines ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39 showed tolerance to Cd and grew normally at both Cd concentrations (Fig. 2, G–L). Further, we investigated the sensitivity of the knockout mutants of FIT (fit1-1, salk_126020), AtbHLH38 (k38, salk_108159), and AtbHLH39 (k39, salk_025676) to Cd exposure. As shown in Supplemental Figure S1, all lines displayed chlorotic growth on the medium containing Cd (Supplemental Fig. S1, C–F). These results show that co-overexpression of FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 and overexpression of AtbHLH39 in Arabidopsis are able to enhance Cd tolerance.

Figure 1.

Expression of transcription factor genes FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 under Cd exposure. The 7-d-old seedlings were transferred to one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates with or without 50 μm CdSO4 for the treatment. Four days later, the relative expression abundance of the three genes in roots of wild type was analyzed by quantitative multiple RT-PCR. Control means normal culture condition without CdSO4 supply, 50 μm Cd means the culture medium with 50 μm CdSO4. The y axis shows RNA levels normalized with that of ACTIN8. n = 3, and values are mean ± sd. **, Significant difference of values at the level of P < 0.01 by Student’s t test in comparison with control.

Figure 2.

Phenotypes of wild type and transgenic lines (ox29, ox38, ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39) on Cd-containing one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates with (A–F) and without (G–L) Fe supply. A and B, Seedlings grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates without CdSO4 as control. C and D, Seedlings grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates with 5 μm CdSO4. E and F, Seedlings grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates with 50 μm CdSO4. G and H, Seedlings grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates without Fe and Cd supply. I and J, Seedlings grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates without Fe and with 5 μm CdSO4. K and L, Seedlings grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates without Fe and with 50 μm CdSO4. The pictures were taken at 7 d after treatment.

ox29/38 and ox29/39 Exhibited Lower Cd Translocation Ratios from Root to Shoot

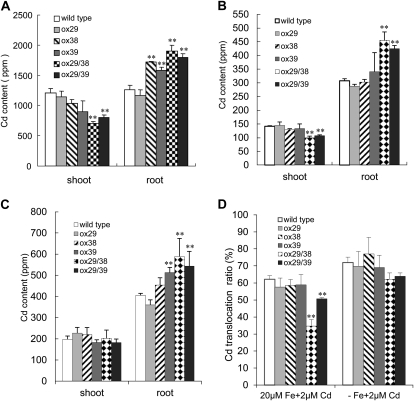

To figure out why ox29/38 and ox29/39 were tolerant to Cd, the Cd content of plants was determined. Wild type and all transgenic lines were firstly grown on a hydroponic system with one-half-strength Hoagland medium (van de Mortel et al., 2006) for 6 weeks and then transferred to the same culture solution with 50 μm CdSO4 and grown for 4 d. Subsequently, the shoots and roots were separately harvested, and their Cd content was determined by an inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES). In shoots, ox29/38 and ox29/39 showed 42% and 32% lower Cd content than wild type, respectively. The Cd content in shoots of ox29, ox38, and ox39 are also lower than that of wild type, but the difference is not significant (Fig. 3A). In roots, the Cd content of ox38, ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39 was about 36%, 25%, 52%, and 42% higher than that of wild type and ox29, respectively (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Cd content of wild type and transgenic lines under culture conditions with CdSO4. Seedlings grown on a modified one-half-strength Hoagland solution (van de Mortel et al., 2006) for 6 weeks were transferred to the same culture solution with 50 or 2 μm CdSO4 and supplemented with 0 and 20 μm Fe-EDTA. A, Cd content of seedlings exposed to 50 μm CdSO4 in the medium with 20 μm Fe. B, Cd content of seedlings exposed to 2 μm CdSO4 in the medium with 20 μm Fe. C, Cd content of seedlings exposed to 2 μm CdSO4 in the medium without Fe supply (−Fe). D, Translocation ratio of Cd (Cd amount in shoot/total Cd amount) of wild type and transgenic lines exposed to 2 μm CdSO4 in the medium with 20 μm Fe-EDTA and without Fe supply. * and **, Significant difference of values at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, by Student’s t test in comparison with wild type.

Considering that the 50 μm CdSO4 used above is much higher than that occurring under field conditions, we further analyzed the Cd accumulation of these transgenic lines grown in hydroponics with a lower Cd concentration (2 μm CdSO4) under Fe-sufficient (20 μm Fe-EDTA) and -deficient (0 μm Fe-EDTA) conditions. Consistent with the results observed above, the Cd content of ox29/38 and ox29/39 was 29% and 24% lower in shoots (Fig. 3B) and 47% and 38.1% higher in roots (Fig. 3B), respectively, than that of wild type under the condition with Fe. No significant difference was observed between wild type and the three other transgenic lines (Fig. 3B). Under the Fe deficiency condition (without Fe supply in culture solution), the wild type and all transgenic lines clearly accumulated much higher Cd content (>30%) in shoots than that under the culture condition with Fe supply, and no significant difference of Cd content in shoots was detected among wild type and the transgenic lines investigated (Fig. 3, B and C). As for shoots, the Fe deficiency stimulated Cd accumulation in roots (Fig. 3, B and C). Additionally, the root Cd content of ox39, ox29/38 and ox29/39 was markedly higher than that of wild type (Fig. 3C).

Furthermore, the Cd translocation ratio to shoots (Cd amount of shoots/total Cd amount) was calculated. Interestingly, ox29/38 and ox29/39 revealed a significantly lower Cd translocation ratio than ox29, ox38, ox39 and wild type under the condition with Fe supply (Fig. 3D).The lower Cd translocation ratio of ox29/38 and ox29/39 was also observed compared to wild type, ox29, ox38, and ox39 under Fe deficiency, but the difference was not significant.

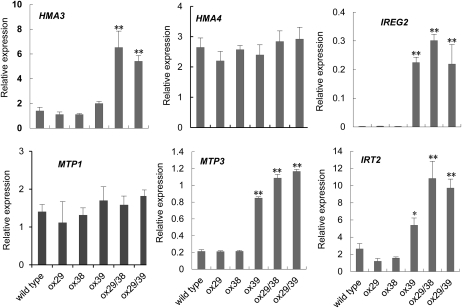

Overexpression of FIT/AtbHLH38 or FIT/AtbHLH39 Changed the Expression Pattern of the Genes Related to Sequestration and Chelation of Heavy Metals

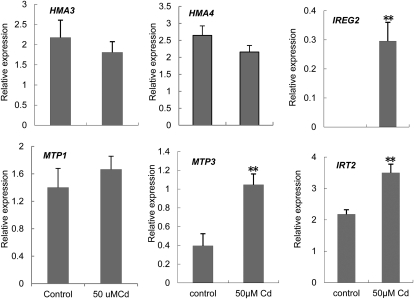

The main mechanisms for detoxification of heavy metals in plants are sequestration of heavy metals into vacuoles (vesicles) or chelation of heavy metals by organic acids or other substances. Considering the lower Cd content in shoots and higher in roots in plants of ox29/38 and ox29/39, we assumed that the absorbed Cd in the two lines might be blocked in the root. Previous and recent results showed that HMA3, HMA4, MTP1, MTP3, and IREG2 are vacuolar membrane-localized metal transporters (Arrivault et al., 2006; Schaaf et al., 2006; Morel et al., 2009), and IRT2 is an intracellular vesicle membrane protein (Vert et al., 2009); they all play an important role in the cytoplasmic detoxification by pumping heavy metals into vacuoles and vesicles of cells, resulting in tolerance to heavy metals. To test whether the Cd tolerance of ox29/38 and ox29/39 is related to these genes, we analyzed the expression intensities of the six genes in wild type under the culture conditions with or without Cd supply by multiplex reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis. As shown in Figure 4, the expression of MTP3, IREG2, and IRT2 was markedly up-regulated upon Cd treatment compared with the control, whereas no significant expression difference of HMA3, HMA4, and MTP1 was observed between the control and Cd treatments. In the transgenic lines, a markedly higher expression of HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, and IRT2 appeared in ox29/38 and ox29/39 even under the culture condition without Cd treatment, and ox39 also displayed a high expression of MTP3, IREG2, and IRT2 in comparison with wild type, whereas ox29 and ox38 displayed a similar expression profile of the four genes to wild type (Fig. 5). All five transgenic lines and wild type displayed a high level of HMA4 and MTP1 expression, and there was no difference among them. Based on these results, we speculate that the Cd tolerance of ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39 might be related to the enhanced expression of HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, and IRT2.

Figure 4.

Expression analysis of the metal detoxification genes HMA3, HMA4, IRT2, IREG2, MTP1, and MTP3 under Cd exposure. The expression of the six genes in wild-type seedlings was analyzed by multiple RT-PCR at 4 d after treatment with 50 μm CdSO4. The y axis shows RNA levels normalized to that of ACTIN8. n = 3, and values are mean ± sd. **, Significant difference of values at the level of P < 0.01 by Student’s t test in comparison with control.

Figure 5.

Expression analysis of HMA3, HMA4, IRT2, IREG2, MTP1, and MTP3 in wild type and transgenic lines under normal culture conditions. The 7-d-old seedlings of wild type and transgenic lines grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium were used for analysis of the expression of the six genes by multiple RT-PCR. The y axis shows RNA levels normalized to that of ACTIN8. n = 3, and values are mean ± sd. * and **, Significant difference values at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, by Student’s t test compared with wild type.

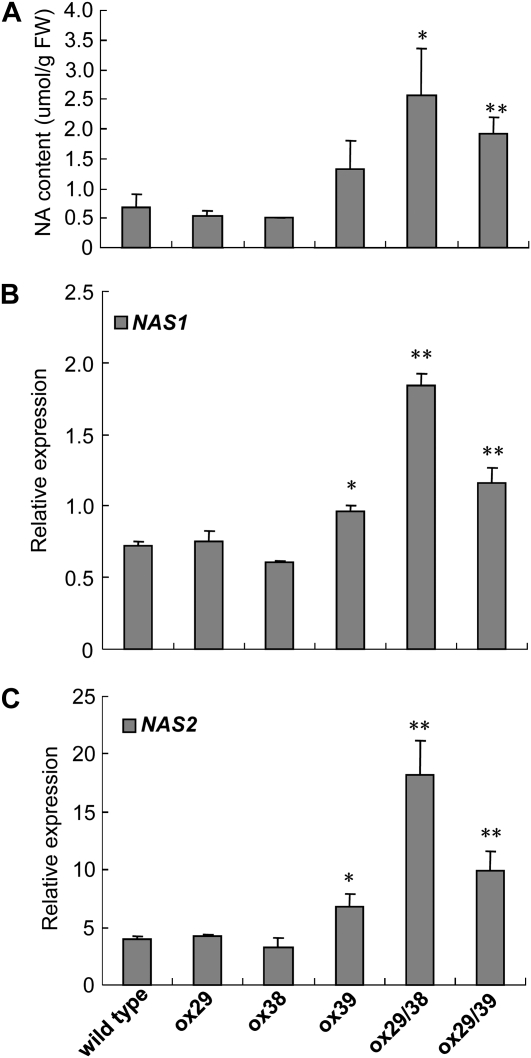

To further investigate the tolerance mechanism of ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39, we analyzed the NA content of wild type and transgenic lines and found that ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39 had a nearly 3-fold higher NA content than that of wild type, ox29, and ox38 plants (Fig. 6A). In Arabidopsis, there are four NAS genes, and they are differentially expressed (Bauer et al., 2004; Klatte et al., 2009). To figure out which genes are responsible for the increased NA content in plants of ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39, we analyzed the expression intensity of the four NAS genes in the five transgenic lines. As shown in Figure 6, B and C, the transcription level of NAS1 and NAS2 was significantly higher in the Cd-tolerant lines ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39 than that of wild type and ox29 and ox38, which were sensitive to Cd exposure, whereas no expression change of NAS3 and NAS4 was observed among the wild type and transgenic lines (data not shown). These indicate that the increased NA in ox39, ox29/38, and ox29/39 is caused by the elevated expression of NAS1 and NAS2. These also imply that the increased NA in plants may directly or indirectly play a role in Cd tolerance.

Figure 6.

NA content measurement and expression pattern of NA synthase genes in wild-type and transgenic lines. A, NA content of 7-d-old seedlings grown in the one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium. B and C, The quantitative analysis of NAS1 and NAS2 expression in 7-d-old seedlings grown in one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium by multiple RT-PCR. The y axis shows RNA levels normalized to that of ACTIN8. n = 3, and values are mean ± sd. * and **, Significant difference of values at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, by Student’s t test compared with wild type.

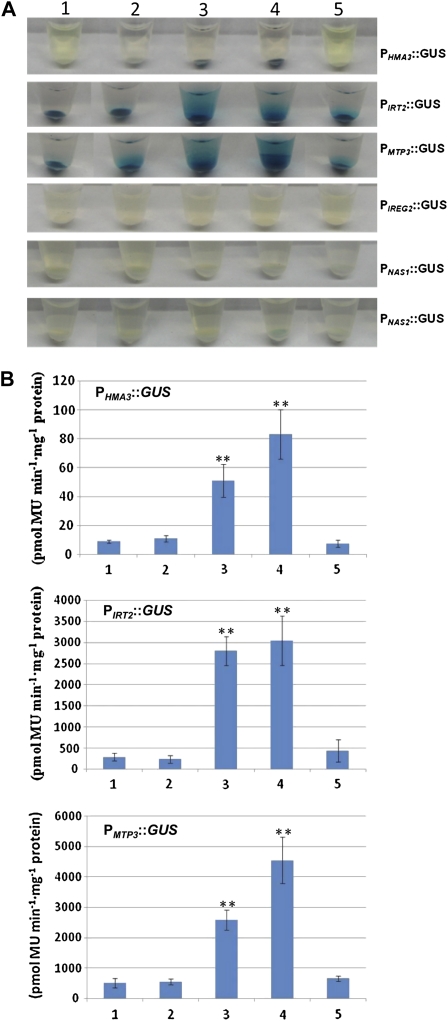

Furthermore, we examined whether the enhanced expression of HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, IRT2, NAS1, and NAS2 in ox29/38 and ox29/39 is directly controlled by the heterodimers of FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39 using a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) assay system (for details, see “Materials and Methods”). GUS-staining assays showed that a blue color appeared in yeast cells containing plasmids pAD-bHLH38/pBD-FIT-PHMA3::GUS or pAD-bHLH39/pBD-FIT-PHMA3::GUS, whereas no blue color was observed in the yeast cells with other plasmid combinations, such as pAD-GAL4/pBD-GAL4-P-HMA3::GUS, pAD-GAL4/pBD-FIT-P-HMA3::GUS, and pAD-AtbHLH39/pBD-GAL4-P-HMA3::GUS (Fig. 7A). Consistent with the GUS staining results, the yeast cells containing the plasmid combinations pAD-bHLH38/pBD-FIT-PHMA3::GUS or pAD-bHLH39/pBD-FIT-PHMA3::GUS exhibited strong GUS activity (Fig. 7B). Because yeast transcription can slightly activate the expression of PIRT2::GUS and PMTP3::GUS in yeast cells, the blue color was observed in all yeast strains containing different plasmid combinations with PIRT2::GUS and PMTP3::GUS by GUS staining assay (Fig. 7A). However, the quantitative analysis revealed that the GUS enzyme activity in yeast cells containing plasmids pAD-bHLH38/pBD-FIT-PIRT2::GUS, pAD-bHLH39/pBD-FIT-PIRT2::GUS, pAD-bHLH38/pBD-FIT-PMTP3::GUS, and pAD-bHLH39/pBD-FIT-PMTP3::GUS were significantly higher than that with other plasmid combinations (Fig. 7B), indicating that the heterodimers FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39 were able to directly activate GUS expression driven by PIRT2 and PMTP3 promoters in yeast cells. Furthermore, yeast cells containing plasmids pAD-bHLH38/pBD-FIT-PIREG2::GUS, pAD-bHLH39/pBD-FIT-PIREG2::GUS, pAD-bHLH38/pBD-FIT-PNAS1::GUS, pAD-bHLH39/pBD-FIT-PNAS1::GUS, pAD-bHLH38/pBD-FIT-PNAS2::GUS, or pAD-bHLH39/pBD-FIT-PNAS2::GUS did not show GUS activity (Fig. 7A), indicating that the increased transcription of AtIREG2, AtNAS1, and AtNAS2 in ox29/38 and ox29/39 are not directly controlled by the heterodimers FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39.

Figure 7.

Assaying transcriptional activation of GUS expression driven by HMA3, IRT2, MTP3, IREG2, NAS1, and NAS2 promoters in yeast cells. A, Qualitative analysis of GUS expression driven by HMA3, IRT2, MTP3, IREG2, NAS1, and NAS2 promoters in yeast strains grown in the synthetic minimal (SM) medium with histidine. B, Quantitative analysis of GUS enzyme activity in yeast cells driven by HMA3, IRT2, and MTP3 promoters. The numbers 1 to 5 indicate plasmid combinations of each gene investigated as follows: 1, pAD-GAL4/pBD-GAL4-P-gene::GUS; 2, pAD-GAL4/pBD-FIT-P-gene::GUS; 3, pAD-AtbHLH38/pBD-FIT-P-gene::GUS; 4, pAD-AtbHLH39/pBD-FIT-P-gene::GUS; and 5, pAD-AtbHLH39/pBD-GAL4-P-gene::GUS. P-gene::GUS represents P-HMA3::GUS, P-IRT2::GUS, P-MTP3::GUS, P-IREG2::GUS, P-NAS1::GUS, and P-NAS2::GUS, respectively. **, Significant difference of values at the level of P < 0.01 by Student’s t test in comparison with control.

Increased Fe Supply Alleviated Cd Toxicity of Plants

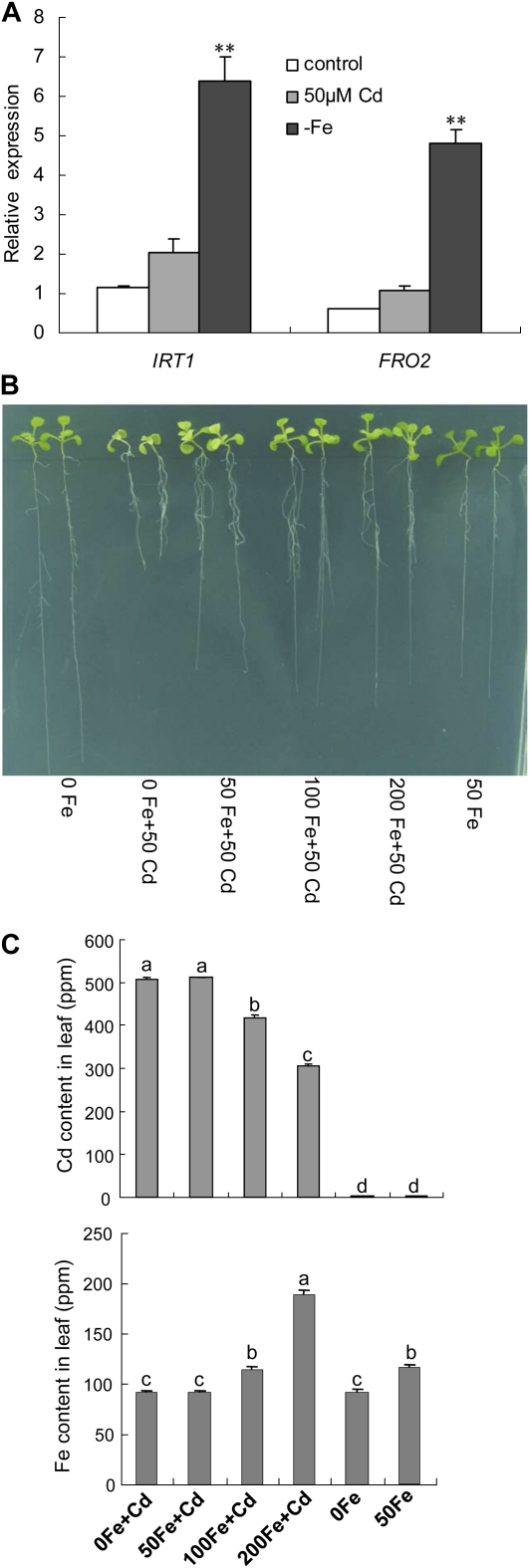

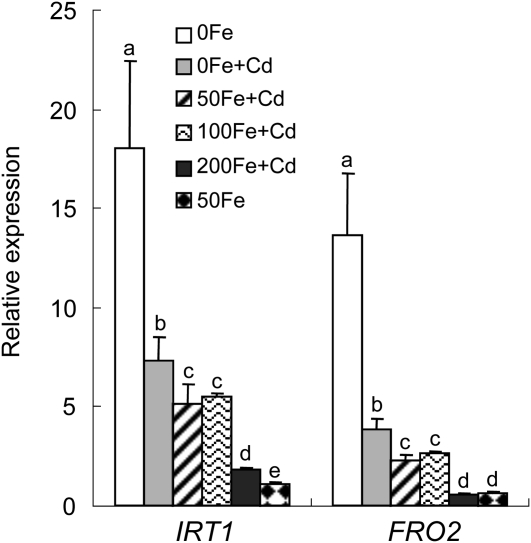

FRO2 and IRT1 are two key genes involved in the Fe homeostasis (Eide et al., 1996; Robinson et al., 1999; Henriques et al., 2002; Varotto et al., 2002; Vert et al., 2002). The two genes also showed up-regulated expression under Cd exposure, although their induced expression levels were lower than those under Fe deficiency (Fig. 8A), implying that the plants may suffer with Fe deficiency under Cd exposure. Hence, increased supply of Fe into medium would be able to alleviate the Cd toxicity of plants. To test the hypothesis, the wild type was cultivated on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium containing 50 μm CdSO4 and different Fe concentrations. As shown in Figure 8B, the chlorosis of new leaves and the block of root growth caused by Cd toxicity were clearly alleviated with increasing Fe supply in the medium. Consistent with the phenotype, the Cd content decreased and the Fe content increased in shoots under Cd exposure with increasing Fe concentrations in the medium (Fig. 8C). Additionally, the IRT1 and FRO2 expression in roots was also down-regulated by adding Fe under Cd exposure (Fig. 9).

Figure 8.

Effect of Fe content on Cd toxicity. A, The expression profiles of IRT1 and FRO2 were characterized by multiple RT-PCR in the 7-d-old wild-type seedlings grown under conditions without (control) and with 50 μm CdSO4 (50 μm Cd) as well as without Fe supply (−Fe) at 4 d. **, Significant difference of values at the level of P < 0.01 by Student’s t test compared with control. B, Phenotypes of the 7-d-old seedlings grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates with different Fe and Cd concentrations. 0, 50, 100, and 200 Fe, Supplementing 0, 50, 100, and 200 μm Fe-EDTA in media, respectively; 50 Cd, adding 50 μm CdSO4 to culture medium. C, Cd and Fe content analysis in wild-type. The 7-d-old seedlings were transferred onto one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates containing 0, 50, 100, and 200 μm Fe-EDTA without and with 50 μm CdSO4, respectively. The Cd and Fe content analysis was performed 4 d after treatment. The different letters over the columns indicate the significant difference among the values at P < 0.05.

Figure 9.

The effect of Cd exposure on expression profiles of IRT1 and FRO2 under different Fe concentrations. The 7-d-old seedlings were transferred to one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates containing 50 μm CdSO4 adding 0, 50, 100, and 200 μm Fe-EDTA, respectively, and grown for 4 d. The expression intensities of IRT1 and FRO2 were analyzed by multiple RT-PCR in their roots. The different letters over the columns indicate the significant difference among the values at P < 0.05.

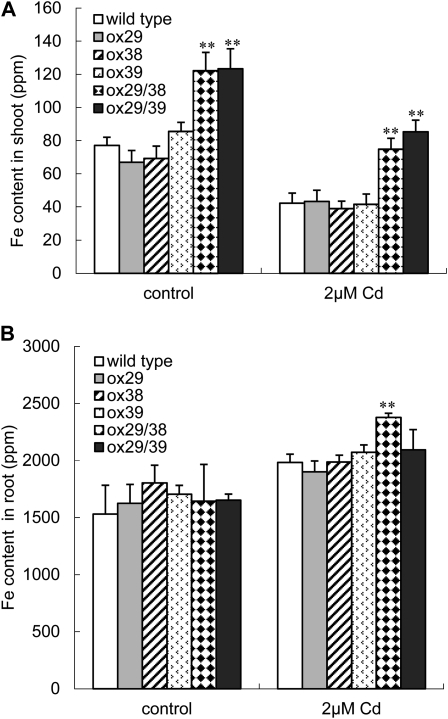

Because IRT1 and FRO2 were constitutively expressed in the ox29/38 and ox29/39 plants, more Fe was taken up and transported to shoots (Yuan et al., 2008). The high Fe in cells may counteract the negative effects of Cd. For testing this hypothesis, the transgenic lines were grown in a hydroponics system with one-half-strength Hoagland solution supplemented with 2 μm CdSO4 and 20 μm Fe-EDTA. The Fe content of their shoots and roots was separately analyzed. As shown in Figure 10, the Fe content decreased more than 50% in shoots and increased more than 15% in roots under exposure to Cd compared with control. Consistent with previous reports, ox29/38 and ox29/39 revealed significantly higher Fe accumulation in shoots than that of wild type and the three other transgenic lines regardless of Cd exposure (Fig. 10A), whereas no difference of Fe content appeared in roots among the all lines investigated with an exception of ox29/38, which accumulated markedly higher Fe content in roots than wild type under the condition with 2 μm CdSO4 (Fig. 10B). Further, we determined the Fe content in shoots of ox29/38 and ox29/39 under Fe deficiency with and without supply of 2 μm CdSO4. Consistent with the results observed under Fe sufficiency, ox29/38 and ox29/39 accumulated significantly more Fe in shoots compared with wild type regardless of the absence and presence of Cd (Supplemental Fig. S2). These results suggest that the elevated Fe content in shoots of ox29/38 and ox29/39, compared with wild type, may play a role in alleviating Cd toxicity and lead to increased Cd tolerance of plants.

Figure 10.

Comparison of shoot and root Fe content in wild-type and transgenic lines. Six-week-old seedlings grown in a one-half-strength Hoagland solution (van de Mortel et al., 2006) were transferred to the same culture solution with 0 and 2 μm CdSO4 and grown for 4 d. Their Fe content in shoots and roots was separately determined by ICP-OES. A, Fe content in shoots of seedlings. B, Fe content in roots of seedlings. * and **, Significant difference of the values at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, by Student’s t test compared with wild type.

DISCUSSION

FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 are basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors that are essential for Fe homeostasis in Arabidopsis (Colangelo and Guerinot, 2004; Jakoby et al., 2004; Yuan et al., 2005, 2008; Wang et al., 2007). In this study, we provide several lines of evidence to support that FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 are involved in Cd tolerance in Arabidopsis. First, we showed that the expression of FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 was up-regulated under Cd exposure (Fig. 1). Second, we demonstrated that plants co-overexpressing FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 exhibited more tolerance to Cd treatment (Fig. 2). Third, we confirmed that the overexpression of FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 constitutively activated expression of HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, IRT2, NAS1, and NAS2, which function in sequestration of heavy metals in vacuoles and vesicles, and in synthesis of NA, which is a major chelator involved in Fe translocation and homeostasis. The higher expression of these genes may be the main reason why ox29/38 and ox29/39 plants revealed more tolerance to Cd.

In a previous study, we confirmed that FIT interacted with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 and formed the heterodimers FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39, directly functioning in control of IRT1 expression. Overexpression of FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 conferred plant constitutive expression of IRT1 and accumulation of its protein product even under Fe-sufficient conditions, resulting in the transgenic plants being more tolerant to low Fe stress (Yuan et al., 2008). Based on the previous findings of IRT1-mediated Cd accumulation in strategy I plants (Cohen et al., 1998; Lombi et al., 2002; Vert et al., 2002; Yoshihara et al., 2006) and overexpression of IRT1 resulting in transgenic plants being more sensitive to Cd (Connolly et al., 2002), ox29/38 and ox29/39 plants, showing a constitutive expression of IRT1, should be sensitive to Cd exposure. Surprisingly, in contrast to 35S-IRT1 transgenic plants, the ox29/38 or ox29/39 plants showed more tolerance to Cd and exhibited a better growth than wild type when exposed to Cd (Fig. 2). Considering that the transgenic plants of ox29/38 and ox29/39 accumulated less Cd in shoots and more in roots than wild type (Fig. 3) suggests that the heterodimers FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39 should activate the expression of some genes related to Cd sequestration. The genes HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, and IRT2, which are involved in sequestration of heavy metals in Arabidopsis, are constitutively expressed in ox29/38 and ox29/39 (Fig. 5). Transcription activation assay showed that the heterodimers FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39 activated the expression of HMA3, MTP3, and IRT2 in yeast cells (Fig. 7). Therefore, we conclude that overexpression of FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 in ox29/38 and ox29/39 constitutively activate the expression of HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, and IRT2 directly or indirectly, and their gene products enhance Cd sequestration in roots and reduce Cd translocation from roots to shoots, consequently making ox29/38 and ox29/39 plants more tolerant to Cd than wild type.

Many reports indicated that the Cd toxicity was mainly caused by disordering the essential metal uptake and homeostasis, especially for the Fe element because the Cd toxicity phenotype and the molecular responses are very similar to Fe deficiency. In this work, we showed that additional supplementation of Fe in medium was clearly able to alleviate the Cd toxicity (Fig. 8B) and repress the molecular responses of Fe deficiency induced by Cd exposure (Fig. 9). Furthermore, the Fe content in wild type and the transgenic lines was significantly decreased (>50%) in shoots (Fig. 10A) and increased (>15%) in roots (Fig. 10B) under Cd exposure compared with control (without Cd supply). These indicate that the Fe homeostasis disorder in plants under Cd exposure is mainly caused by lowering Fe translocation from roots to shoots due to ion competition but not by uptake.

NA, a major chelator of ferrous Fe, is thought to play important roles in Fe long-distance transportation and transfer within cells. In ox29/38 and ox29/39, overexpression of FIT/AtbHLH38 and FIT/AtbHLH39 led to a higher level expression of NAS1 and NAS2 and to NA accumulation (Fig. 6A). The higher level of NA content will enhance the Fe translocation from root to shoot and stimulate Fe accumulation in shoots of the two lines even under Cd exposure. Actually, the shoots of ox29/38 and ox29/39 accumulated more than 1.5 times more Fe than that of wild type (Fig. 10A). Furthermore, additional supplementation of Fe into Cd-containing medium alleviated toxic phenotype of Cd (Fig. 8B). These suggest that the high Fe content in shoots of ox29/38 and ox29/39 must play a role in alleviation of Cd toxicity and tolerance in addition to Cd sequestration in roots. Considering that Cd toxicity is mainly attributed to the competition of metal-binding molecules with other essential metals, especially Fe (Schützendübel and Polle, 2002), we speculate that improved Fe status in cells of ox29/38 and ox29/39 would inhibit or reduce the Cd ion to bind the metal-binding molecules, resulting in alleviation of Cd toxicity.

The Cd tolerance of plants is a very sophisticated process in which different physiological and molecular mechanisms are involved, such as cell wall binding, chelation with phytochelatins, compartmentation in vacuole, enrichment in leaf trichomes, reduced uptake from soil, low translocation from root to shoot, and so on. The tolerant phenotype observed in plants is usually unable to be explained simply by one of the mechanisms. It is often a result of several mechanisms that function together. According to our results described above, the higher level of Cd tolerance of ox29/38 and ox29/39 should be the functional consequence of two Cd detoxification mechanisms: 1) Overexpression of FIT with AtbHLH38 and FIT with AtbHLH39 in ox29/38 and ox29/39, respectively, constitutively activates the expression of HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, and IRT2, enhancing Cd sequestration in roots and reducing Cd translocation from roots to shoots; and 2) Constitutive expression of IRT1, FRO2, NAS1, and NAS2 (genes involved in Fe uptake and translocation) in ox29/38 and ox29/39 promote Fe uptake and accumulation in shoots, resulting in inhibition or reduction of Cd to bind the essential metal-binding molecules in cells.

As shown in Figure 2, ox39 overexpressing AtbHLH39 displayed more tolerance to Cd than ox29 and ox38, which overexpressed FIT and AtbHLH38, respectively. This can be explained by the increased expression of MTP3, IRT2, IREG2, NAS1, and NAS2 in ox39, but not in ox29 and ox38 (Figs. 5 and 6). Based on the results of our previous studies (Yuan et al., 2008) and this work, AtbHLH39 protein is not able to form a homodimer to activate the expression of downstream genes. The elevated expression of MTP3, IRT2, IREG2, NAS1, and NAS2 in ox39 should be regulated by interaction of the AtbHLH39 protein with unknown factor(s). Further studies are needed to find out the factor(s).

In summary, this work provides the first description, to our knowledge, that the bHLH transcription factors FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 function in plant tolerance to Cd. Co-overexpression of FIT with AtbHLH38 or AtbHLH39 in Arabidopsis constitutively activated the expression of HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, IRT2, NAS1, and NAS2 directly or indirectly, resulting in Cd sequestration in roots to maintain a relatively low cellular Cd concentration in shoots and enhancement of Fe transportation from root to shoot to keep the Fe homeostasis in shoots. These two factors may contribute to ox29/38 and ox29/39 plants more tolerance to Cd under the culture condition with Cd. Our results provide a new insight to understand the molecular mechanisms of Cd tolerance and a potential way to control Cd accumulation in plants by genetic improvement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth Conditions

Seeds of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; ecotype Columbia), transgenic, and T-DNA insertion lines were surface sterilized with 10% commercial bleach for 10 min and then washed three times with distilled water. After vernalization at 4°C in the dark for 2 d, the seeds were sown on plates with one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog basal salt medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) supplemented with 2% sucrose and 0.8% agar at pH 5.8. The plates were incubated at 23°C with a 16-h light period for 7 d. The seedlings were then used for further analysis.

For the experiments of Cd toxicity, 7-d-old seedlings were transferred onto one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates with various Fe and Cd concentrations. To investigate the effect of Fe on Cd toxicity, 7-d-old seedlings were transferred onto one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog agar plates with 50 μm CdSO4 supplementing 0, 50, 100, and 200 μm Fe-EDTA. After growing for 4 d in the growth chamber with a 16-h light period, shoots and roots of plants were separately harvested. A part of the shoots and the whole roots were used for extraction of total RNAs with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) for studying gene expression profiles, and the rest of the shoots were used for determination of Cd and Fe contents.

Determination of Cd and Fe Contents

Seedlings of Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia-0 and transgenic lines were grown on a modified one-half-strength Hoagland solution as described by van de Mortel et al. (2006) for 6 weeks. The plants were transferred to the same modified one-half-strength Hoagland solution supplied with various Fe and Cd concentrations. Four days later, the plants were harvested after desorbing the root system with ice-cold 5 mm PbNO3 for 30 min. Roots and shoots were dried overnight at 65°C. Elemental analysis was performed by an ICP-OES (Perkin Elmer) as described by Yuan et al. (2008). sds were calculated for three biological replicates.

Multiplex RT-PCR Analysis

The expression patterns of genes were detected using the GenomeLab GeXP Analysis System Multiplex RT-PCR assay (Beckman) according to the protocol described by Chen et al. (2007) and Yuan et al. (2008). The housekeeping gene AtACTIN8 (At1g49240) was used as the control. The gene expression data obtained from multiplex RT-PCR were normalized by dividing the peak area value of each gene with the peak area value of AtACTIN8. The primers used in the multiplex RT-PCR reactions are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

NA Measurement

NA was extracted and measured as described by Le Jean et al. (2005). Quantification was carried out using pure chemically synthesized NA (T-Hasegawa) as an external standard. sds were calculated for three biological replicates.

Transcription Activation Assay of FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 in Yeast Cells

A yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) assay system was designed as described by Yuan et al. (2008) for characterizing transcriptional activation of FIT, AtbHLH38, and AtbHLH39 on their potential target genes. Briefly, the HMA3 promoter (1,316 bp upstream of HMA3 start codon, named PHMA3), the MTP3 promoter (624 bp upstream of MTP3 start codon, named PMTP3), the IREG2 promoter (1,751 bp upstream of IREG2 start codon, named PIREG2), the IRT2 promoter (sequence from 8 to 1,248 bp upstream of IRT2 start codon, named PIRT2), the NAS1 promoter (1,143 bp upstream of NAS1 start codon, named PNAS1), and the NAS2 promoter (1,370 bp upstream of NAS2 start codon, named PNAS2) were amplified by PCR with primers listed in Supplemental Table S1 and cloned into the PMD18-T vector (TaKaRa Biotechnology). They were sequenced for confirmation of sequence. Subsequently, the promoter DNA fragment was excised from the PMD18-T vector using corresponding restriction endonucleases and replaced by the 2×35S promoter of pJIT166 plasmid (pGreen; http://www.pgreen.ac.uk). The GUS expression cassettes with the HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, NAS1, and NAS2 promoters and the cauliflower mosaic virus terminator were cut out from the pJIT166 derivatives with the SacI/XhoI, PIRT2::GUS::CaMV cassette from the pJIT166 derivative with SacI/SphI, blunted, and integrated into the PmacI site of pBD-GAL4 and pBD-FIT to generate yeast expression plasmids pBD-GAL4-PHMA3::GUS, pBD-GAL4-PMTP3::GUS, pBD-GAL4-PIREG2::GUS, pBD-GAL4-PIRT2::GUS, pBD-GAL4-PNAS1::GUS, pBD-GAL4-PNAS2::GUS, pBD-FIT-PHMA3::GUS, pBD-FIT-PMTP3::GUS, pBD-FIT-PIREG2::GUS, pBD-FIT-PIRT2::GUS, pBD-FIT-PNAS1::GUS, and pBD-FIT-PNAS2::GUS. The plasmids were then introduced into yeast strain YRG-2 in pairs with pAD-GAL4, pAD-bHLH38, and pAD-bHLH39. For each gene, the plasmid combinations are as follows: pAD-GAL4/pBD-GAL4-Pgene::GUS, pAD-GAL4/pBD-FIT-Pgene::GUS, pAD-AtbHLH38/pBD-FIT-Pgene::GUS, pAD-AtbHLH39/pBD-FIT-Pgene::GUS, and pAD-AtbHLH39/pBD-GAL4-Pgene::GUS. The Pgene::GUS of each set of plasmid combinations represents PHMA3::GUS, PMTP3::GUS, PIREG2::GUS, PIRT2::GUS, PNAS1::GUS, and PNAS2::GUS, respectively.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Cd sensitivity test of knockout mutants fit1-1 (knockout mutant of FIT), k38 (knockout mutant of AtbHLH38), and k39 (knockout mutant of AtbHLH39).

Supplemental Figure S2. Fe content in shoots of plants grown under Fe deficiency with 0 and 2 μm CdSO4.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used in this work.

Supplementary Material

References

- Arrivault S, Senger T, Krämer U. (2006) The Arabidopsis metal tolerance protein AtMTP3 maintains metal homeostasis by mediating Zn exclusion from the shoot under Fe deficiency and Zn oversupply. Plant J 46: 861–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer P, Thiel T, Klatte M, Bereczky Z, Brumbarova T, Hell R, Grosse I. (2004) Analysis of sequence, map position, and gene expression reveals conserved essential genes for iron uptake in Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant Physiol 136: 4169–4183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson-Bard A, Gravot A, Richaud P, Auroy P, Duc C, Gaymard F, Taconnat L, Renou JP, Pugin A, Wendehenne D. (2009) Nitric oxide contributes to cadmium toxicity in Arabidopsis by promoting cadmium accumulation in roots and by up-regulating genes related to iron uptake. Plant Physiol 149: 1302–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QR, Vansant G, Oades K, Pickering M, Wei JS, Song YK, Monforte J, Khan J. (2007) Diagnosis of the small round blue cell tumors using multiplex polymerase chain reaction. J Mol Diagn 9: 80–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S. (2006) Toxic metal accumulation, responses to exposure and mechanisms of tolerance in plants. Biochimie 88: 1707–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CK, Fox TC, Garvin DF, Kochian LV. (1998) The role of iron-deficiency stress responses in stimulating heavy-metal transport in plants. Plant Physiol 116: 1063–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo EP, Guerinot ML. (2004) The essential basic helix-loop-helix protein FIT1 is required for the iron deficiency response. Plant Cell 16: 3400–3412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly EL, Fett JP, Guerinot ML. (2002) Expression of the IRT1 metal transporter is controlled by metals at the levels of transcript and protein accumulation. Plant Cell 14: 1347–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Samantaray S, Rout GR. (1997) Studies on cadmium toxicity in plants: a review. Environ Pollut 98: 29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide D, Broderius M, Fett J, Guerinot ML. (1996) A novel iron-regulated metal transporter from plants identified by functional expression in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 5624–5628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques R, Jásik J, Klein M, Martinoia E, Feller U, Schell J, Pais MS, Koncz C. (2002) Knock-out of Arabidopsis metal transporter gene IRT1 results in iron deficiency accompanied by cell differentiation defects. Plant Mol Biol 50: 587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakoby M, Wang HY, Reidt W, Weisshaar B, Bauer P. (2004) FRU (BHLH029) is required for induction of iron mobilization genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett 577: 528–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle H. (1993) Response of roots of trees to heavy metals. Environ Exp Bot 33: 99–119 [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Takahashi M, Higuchi K, Tsunoda K, Nakanishi H, Yoshimura E, Mori S, Nishizawa NK. (2005) Increased nicotianamine biosynthesis confers enhanced tolerance of high levels of metals, in particular nickel, to plants. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 1809–1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatte M, Schuler M, Wirtz M, Fink-Straube C, Hell R, Bauer P. (2009) The analysis of Arabidopsis nicotianamine synthase mutants reveals functions for nicotianamine in seed iron loading and iron deficiency responses. Plant Physiol 150: 257–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jean M, Schikora A, Mari S, Briat JF, Curie C. (2005) A loss-of-function mutation in AtYSL1 reveals its role in iron and nicotianamine seed loading. Plant J 44: 769–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H-Q, Bauer P, Bereczky Z, Keller B, Ganal M. (2002) The tomato fer gene encoding a bHLH protein controls iron-uptake responses in roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 13938–13943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombi E, Tearall KL, Howarth JR, Zhao FJ, Hawkesford MJ, McGrath SP. (2002) Influence of iron status on cadmium and zinc uptake by different ecotypes of the hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. Plant Physiol 128: 1359–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel M, Crouzet J, Gravot A, Auroy P, Leonhardt N, Vavasseur A, Richaud P. (2009) AtHMA3, a P1B-ATPase allowing Cd/Zn/Co/Pb vacuolar storage in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 149: 894–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant 15: 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NJ, Procter CM, Connolly EL, Guerinot MLA. (1999) A ferric-chelate reductase for iron uptake from soils. Nature 397: 694–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodecap KD, Tingey DT, Lee EH. (1994) Iron nutrition influence on cadmium accumulation by Arabidopsis thaliana L. Heynh. J Environ Qual 23: 239–246 [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf G, Honsbein A, Meda AR, Kirchner S, Wipf D, von Wirén N. (2006) AtIREG2 encodes a tonoplast transport protein involved in iron-dependent nickel detoxification in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. J Biol Chem 281: 25532–25540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schützendübel A, Polle A. (2002) Plant responses to abiotic stresses: heavy metal-induced oxidative stress and protection by mycorrhization. J Exp Bot 53: 1351–1365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Mortel JE, Almar Villanueva L, Schat H, Kwekkeboom J, Coughlan S, Moerland PD, Ver Loren van Themaat E, Koornneef M, Aarts MG. (2006) Large expression differences in genes for iron and zinc homeostasis, stress response, and lignin biosynthesis distinguish roots of Arabidopsis thaliana and the related metal hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. Plant Physiol 142: 1127–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varotto C, Maiwald D, Pesaresi P, Jahns P, Salamini F, Leister D. (2002) The metal ion transporter IRT1 is necessary for iron homeostasis and efficient photosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 31: 589–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert G, Barberon M, Zelazny E, Séguéla M, Briat JF, Curie C. (2009) Arabidopsis IRT2 cooperates with the high-affinity iron uptake system to maintain iron homeostasis in root epidermal cells. Planta 229: 1171–1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert G, Grotz N, Dédaldéchamp F, Gaymard F, Guerinot ML, Briat JF, Curie C. (2002) IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 14: 1223–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Klatte M, Jakoby M, Bäumlein H, Weisshaar B, Bauer P. (2007) Iron deficiency-mediated stress regulation of four subgroup Ib BHLH genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 226: 897–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch RM, Norvell WA, Schaefer SC, Shaff JE, Kochian LV. (1993) Induction of iron(III) and copper(II) reduction in pea (Pisum sativum) roots by Fe and Cu status: does the root-cell plasmalemma Fe(III)-chelate reductase perform a general role in regulating cation uptake? Planta 190: 555–561 [Google Scholar]

- Yi Y, Guerinot ML. (1996) Genetic evidence that induction of root Fe(III) chelate reductase activity is necessary for iron uptake under iron deficiency. Plant J 10: 835–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara T, Hodoshima H, Miyano Y, Shoji K, Shimada H, Goto F. (2006) Cadmium inducible Fe deficiency responses observed from macro and molecular views in tobacco plants. Plant Cell Rep 25: 365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, Wu H, Wang N, Li J, Zhao W, Du J, Wang D, Ling H-Q. (2008) FIT interacts with AtbHLH38 and AtbHLH39 in regulating iron uptake gene expression for iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Cell Res 18: 385–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YX, Zhang J, Wang DW, Ling H-Q. (2005) AtbHLH29 of Arabidopsis thaliana is a functional ortholog of tomato FER involved in controlling iron acquisition in strategy I plants. Cell Res 15: 613–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.