Abstract

This cross-sectional study examined family functioning and normalization in 103 mothers of children ≤16 years of age dependent on medical technology (mechanical ventilation, intravenous nutrition/medication, respiratory/nutritional support) following initiation of home care. Differences in outcomes (mother’s depressive symptoms, normalization, family functioning), based on the type of technology used, were also examined. Participants were interviewed face-to-face using the Demographic Characteristics Questionnaire, the Functional Status II-Revised Scale, the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale, a Normalization Scale subscale, and the Feetham Family Functioning Survey. Thirty-five percent of the variance in family functioning was explained primarily by the mothers’ level of depressive symptoms. Several variables were significant predictors of normalization. Analysis of variance revealed no significant difference in outcomes based upon the type of technology used. Mothers of technology-dependent children are at high risk for clinical depression that may affect family functioning. This article concludes with clinical practice and policy implications.

Keywords: technology-dependent, children, normalization, family functioning, chronic illness

Technological and scientific advances over the past 20 years have increased the survival rate of chronically ill children in the United States, but have resulted in a dependency on technology and home care for their continued survival (Guyer, MacDorman, Martin, Peters, & Strobino, 1998; Jackson Allen, 2004; Madigan, Youngblut, & Haruzivishe, 1999). In 1987, The Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) estimated that 11,000 to 68,000 children in the U. S. were dependent on 4 medical technology groups, including mechanical ventilation (Group 1), intravenous nutrition or medication (Group 2), respiratory or nutritional support (Group 3), or apnea monitors (Group 4), and were receiving home care. While no current estimate of the total number of technology-dependent children exists, a 2004 survey of North Carolina Medicaid recipients indicated that 1,914 children were classified as technology-dependent (Buescher, Whitmire, Brunssen, & Kluttz-Hille, 2006). This data from only 1 state, when compared to the OTA (1987) estimate, strongly suggests that the population of children in the U. S. who are technology-dependent has increased exponentially over the last 20 years.

The Burden of Care for Technology-Dependent Children

The bulk of care for technology-dependent children is provided by their mothers. Managing the demanding care regimens of these children makes it difficult for many families to maintain a “normal” family life. The present study examined family functioning and normalization, the process that families use over time that allows them to redefine what normal is to fit their current circumstances (Knafl & Deatrick, 2002) in families with technology-dependent children following initiation of home care.

Families experience a tremendous burden related to the at-home care for a child who is technology-dependent. This burden includes the time required for the care and the treatments necessary to sustain the child (Heyman et al., 2004; Kirk & Glendinning, 2004; Wilson, Morse, & Penrod, 1998), possible social isolation (Carnevale, Alexander, Davis, Rennick, & Troini, 2006; O’Brien, 2001), increased expenditures (Glendinning, Kirk, Guiffrida, & Lawton, 2001; Newacheck & Kim, 2005), and a toll on psychological health (Miles, Holditch-Davis, Burchinal, & Nelson, 1999; Leonard, Brust, & Nelson, 1993). Families who initiate home care for their technology-dependent children undergo major lifestyle changes that affect family functioning (Cohen, 1999; Murphy, 1997; O’Brien & Wegner, 2002) and the family’s “normalcy lens,” i.e., how a family chooses to view their circumstances (Deatrick, Knafl, & Murphy-Moore, 1999).

The entire family is affected by a child who is technology-dependent, causing a change in family functioning due to the increased care demands (Knafl, Breitmayer, Gallo, & Zoeller, 1996). The initiation of home care for a technology-dependent child may result in impaired individual and family growth or system dysfunction, lack of stability and predictability, and possible physical and mental health problems of the members (Clawson, 1996; Miles et al., 1999). Few quantitative research studies have been conducted in this area. Researchers have examined depressive symptoms experienced by parents (Fleming et al., 1994; Heyman et al., 2004; Kuster & Badr, 2006; Miles et al., 1999; Teague et al., 1993), the impact on the family relative to the OTA’s (1987) established medical technology groups (Fleming et al., 1994; Leonard et al., 1993), maternal health promotion activities (Kuster & Badr, 2006), and severity of the child’s illness (Miles et al., 1999), but have not examined how personal characteristics of parents and their technology-dependent children affect parental depressive symptoms, normalization, or family function, thus there is little evidence to guide the delivery of nursing care for this population. Such information is vital for maintaining the mental health of caregivers and positive family functioning, which in the long term affect the child’s growth and development (Miles, et al., 1999).

Theoretical Frameworks and Research Questions

The theoretical frameworks guiding this study were the Family Management Style (FMS) Framework developed by Knafl and Deatrick (2003) and Paterson’s (2001) “Shifting Perspectives Model of Chronic Illness.” The FMS Framework provides a description of how families manage both family life and their children’s complex health problems (Deatrick et al., 2006). Families, to varying degrees, strive toward the incorporation of normalization, depending upon each family’s definition of the situation, in the way they manage their children’s complex care needs, and perceived future consequences of a child’s condition-- both for the child and family life (Deatrick et al., 2006). Most families who have children with serious illnesses eventually view their children and their lives as normal and manage the illness-related demands successfully (Deatrick et al., 2006). However, not all families see their lives as normal, and those who do reach this point often use a variety of strategies over time as they undergo a continual process of adjustment. Normalization efforts are thought to affect outcomes such as individual functioning (for example, depressive symptoms), and family functioning (Deatrick et al., 2006). In this study, normalization efforts are defined as the adjustment families with technology-dependent children make over time to meet their children’s care needs as well as manage family life and activities so that they can lead as close to a normal family life as possible.

Paterson’s Model (2001) proposes that living with a chronic illness is an ongoing, continually shifting process whereby the illness is sometimes in the foreground, and at other times, in the background. When illness is in the foreground, the focus is on the sickness, but when it’s in the background, the family’s focus shifts to the health and well-being of the entire family. The Paterson Model (2001) and FMS Framework (Knafl & Deatrick, 2003) blend as both highlight the importance of perception and help to explain how families develop the normalcy lens, an attribute of normalization. Severity of illness, characterized by poor illness control (Dashiff, 1993), unpredictability (Cohen, 1993; Haase, & Rostad, 1994), or exacerbations of the illness (Knafl & Deatrick, 2002), bring the illness to the foreground and are thought to decrease the sense of normalization experienced by families. Mothers who reported that their children’s illness is disruptive and had a major impact on family life had more depressive symptoms (Frankel & Wamboldt, 1998). The depressive symptoms are proposed to affect how mothers define or appraise the situation, a key component of normalization, and are hypothesized to affect family functioning. Therefore, a mother’s depressive symptoms (Frankel & Wamboldt, 1998) and her child’s severity of illness (Knafl & Deatrick, 2002; Murphy, 1994; O’Brien & Wegner, 2002; Rehm & Bradley, 2005) affect normalization efforts, and consequently, family functioning (Frankel & Wamboldt, 1998).

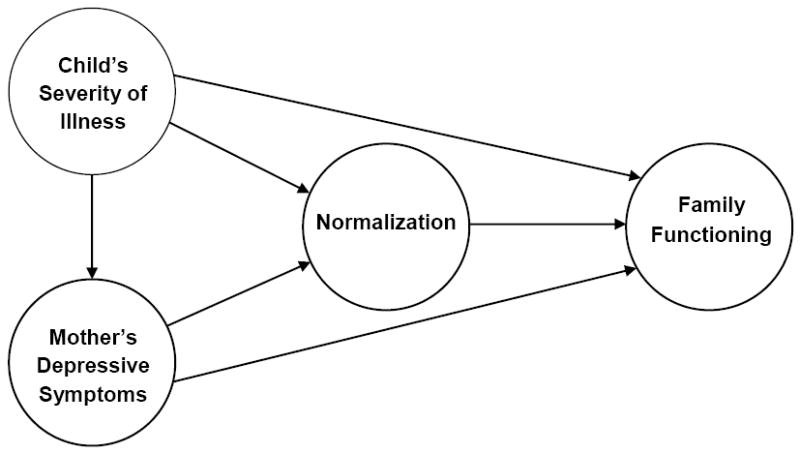

Based on a synthesis of the theoretical and empirical literature, it is proposed in this study (Figure 1) that the child’s severity of illness (Ostwald et al., 1993), mother’s depressive symptoms (Kuster, 2004), and normalization efforts (Knafl & Zoeller, 2000) all directly affect family functioning. In addition, a direct effect is proposed between the child’s severity of illness and mother’s depressive symptoms (Frankel & Wamboldt, 1998). Both are then hypothesized to have direct effects on normalization efforts (Murphy, 1994) and family functioning (Frankel & Wamboldt, 1998). A mother’s depressive symptoms are proposed to be a mediator between her child’s severity of illness and family functioning, as well as a mediator between her child’s severity of illness and normalization efforts. Normalization is proposed to mediate the relationship between a child’s severity of illness and family functioning, as well as the mother’s depressive symptoms and family functioning.

Figure 1.

A Conceptual Model of Family Functioning in Families with a Child who is Technology-dependent.

The proposed covariates (caregiving duration, amount of home healthcare nursing hours, race, family income, and child’s age), were included to permit statistical adjustment in multiple regression analyses to control for their differences in study variables (Figure 1). Additionally, the covariates’ inclusion is based upon past empirical evidence indicating a significant relationship with study variables (Murphy, 1994; O’Brien & Wegner, 2002; Zauszniewski & Wykle, 1994).

In the present study, the following research questions were addressed: 1) Are there differences in (a) family functioning and (b) normalization efforts and (c) mother’s level of depressive symptoms based on the child’s level of technology dependence?; 2) (a) What are the relationships of mother’s depressive symptoms, child’s severity of illness (functional status and level of technology dependence), and normalization efforts with family functioning in families with technology-dependent children?; and (b) Do these relationships hold after adjusting for length of caregiving duration, home healthcare nursing hours, race, family income, and age of the child?; 3) Do a mother’s depressive symptoms have a mediating effect on the relationship between the child’s severity of illness (functional status) and normalization efforts and family functioning in mothers with technology-dependent children?; 4) Does normalization have a mediating effect on the relationship between (a) the child’s severity of illness (functional status) and family functioning, and (b) depressive symptoms and family functioning in mothers with technology-dependent children? ; 5) (a) What are the relationships among mother’s depressive symptoms, child’s severity of illness (functional status, level of technology dependence), and family functioning on normalization efforts in families with technology-dependent children?; and (b) Do these relationships hold after adjusting for length of caregiving duration, home healthcare nursing hours, race, family income, and age of the child?

Method

Design and Sample

A descriptive, correlational, cross-sectional study design was used to explore the relationships between a child’s severity of illness, the mother’s depressive symptoms, and normalization efforts with family functioning in families with technology-dependent children. A convenience sample of 103 mothers who care for technology-dependent children at home was enrolled in this study. Inclusion criteria were mothers who were: 1) 18 years of age and older; 2) caring for a child who is technology-dependent upon medical equipment or support outlined in the OTA Groups 1, 2, or 3 with a stable course of illness, 16 years of age or younger for a minimum of 2 months prior to study participation; and 3) able to speak and understand English. Excluded were mothers of children with cancer or in the terminal stage of illness. The study participants were identified and recruited from the Pulmonology, Gastroenterology, Otolaryngology, Pediatric Surgery, and Preterm Infant Follow-up Clinics and the Family Learning Center at Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital of University Hospital Case Medical Center (UHCMC) in Cleveland, Ohio, or by a primary care physician, or were referred by other participants. The sample size was determined by an a priori power analysis (Cohen, 1992) for hierarchical multiple regression (HMR) analysis using a medium effect size of .15, due to lack of research in this area, along with an alpha of .05 and a power of .80.

Procedure and Instruments

The UHCMC Institutional Review Board (IRB) in Cleveland, Ohio, approved the study. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with mothers in outpatient clinics (n=38, 36.9%) or in another private place of the mother’s choosing, such as their home or the clinical research unit (n=62, 63.1%). Informed consent and HIPAA authorization were obtained on IRB-approved forms prior to data collection. Confidentiality was maintained by using code numbers on questionnaires. Following completion of all study components, participants were given a $15 gift card for their time. Interviews ranged from 45-90 minutes (M=55).

Six instruments were used in this study. The Functional Status II-Revised (FS II-R) was used to measure a child’s functional status (Stein & Jessop, 1990). The 14-item scale (α=.86) is administered in 2 parts. In part 1, parents were asked about the child’s performance of an activity or behavior in the past 2 weeks, with responses ranging from never/rarely (0) to almost always (2); and in Part 2, responses indicating poor function were examined to determine whether the reasons were fully (2) or not at all (0) due to illness (Stein & Jessop, 1990). Sample items included whether the child eats well, sleeps well, and seems lively and energetic. Scores were summed and converted to a percent of the 28 points possible, with higher scores indicating higher function (Stein & Jessop, 1990). Cronbach’s alpha of this instrument in the current study was .76.

The Level of Technology Dependency Questionnaire, based on the OTA (1987) medical technology dependence groups (Group 1, 2, or 3), was used, for purposes of group assignment to assess the technology the child required. If the child required technology from more than one group, he or she was assigned to the applicable group with the lowest group number. Past studies (Leonard et al., 1993; Fleming et al., 1994) have used the OTA technology group designations.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to measure the mother’s level of depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). This scale is widely used and was designed for general population surveys to examine relationships between depressive symptoms and other variables across population subgroups. The CES-D measures possible depressive reactions in response to life events and differentiates significantly between clinical psychiatric inpatients and the general population (Radloff, 1977). The 20-item interval scale (α =.85) with responses ranging from rarely (0) to most or all of the time (3) is summed, and higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. Sample items in the scale include, for example, how frequently during the past week the subject did not feel like eating or had trouble keeping mentally focused on what she was doing. A cut-off score of 16 was used to identify those at high risk for clinical depression (Radloff, 1977). Cronbach’s alpha of this instrument in the current study was .92.

“Actual Effect of the Chronic Physical Disorder on the Family”, a 10-item visual analog subscale (α =.84) of the 25-item Normalization Scale, was used to measure normalization efforts. The Normalization Scale (Murphy & Gottlieb, 1992), was derived from work by Knafl and Deatrick on normalization attributes and the FMS Framework. This subscale includes items assessing the impact of a chronic physical disorder on the family’s activities. A visual analog scale format was used to reduce bias and assist in measurement of subjective experiences (Murphy, 1994). Construct validity was assessed using principal components analysis (Murphy, 1994). Cronbach’s alpha of this instrument in the current study was .83.

The Feetham Family Functioning Survey (FFFS), a 25-item scale (α =.85), was used to measure family functioning (Roberts & Feetham, 1982). Reponses on a 7-point Likert scale ranged from little (1) to much (7). Each item in the survey has 3 questions: (a) How much is there now?; (b) How much should there be?; and (c) How important is this to you? This Porter format provided a discrepancy score, with higher scores reflecting greater dissatisfaction with family functioning. Sample questions included asking subjects about the amount of discussion they had with friends regarding concerns and problems, and the amount of time their work routines were disrupted (Roberts & Feetham, 1982). Cronbach’s alpha of this instrument in the current study was .87.

The Demographic Characteristics Questionnaire included questions regarding the child’s age, the mother’s age, her relationship with the child, her education, and her employment status (Toly, 2009). Questions include additional covariates such as caregiving duration, home healthcare nursing hours, and family income. The FS II-R and the Level of Technology Dependency questionnaires were administered by the data collector and the remaining instruments were self-administered.

Statistical Analysis

Data from all the 6 instruments were entered into the SPSS 15.0 software package. Preliminary analysis of study variables included frequencies, descriptive statistics, and a Pearson correlation matrix. The assumptions of HMR analysis and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were examined (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007) and found to be satisfactorily met. Missing data were handled using case mean substitution.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participants (N=103) were mothers primarily from Northeastern Ohio and were recruited mainly from Pulmonology (n=56, 54.4%) and Gastroenterology (n=18, 17.5%) clinics. The remaining participants were recruited from Otolaryngology (n=4, 3.9%), Pediatric Surgery (n=11, 10.7%), and Preterm Infant Follow-up (n=5, 4.9%) clinics or a primary care office or referred by other participants (n=9, 8.7%). The response rate was 88.7% (110/124) with a participation rate of 93.6% (103/110). Mothers in this study ranged in age from 21-66 years (M=37.87, SD=9.35). The race of participants was predominately Caucasian (n=82, 79.6%), including those of Hispanic ethnicity (n=6); however, the percentage of participants from other races, such as African American (n=17, 16.5%), Asian (n=2, 1.9%), and Biracial (n=1, 1%), mirrors the demographics of the region. The mothers possessed a wide variation of educational backgrounds, but the majority (68.9%) had at least a partial college education. A majority of the participants (n=88%, 85.4%) were the biological mother’s of the children, but there were some adoptive (n=8, 7.8%) and foster (n=5, 4.9%) mothers as well as grandmothers (n=2, 1.9%) with primary caretaking responsibility. Most participants were married (n=73, 70.9%). Almost half of the participants were not employed outside the home (n=47, 45.6%), while others worked full-time 40 hours or more per week (n=28, 27.2%). Yearly total family income varied: about half of families earned $60,000 or less (n=52, 50.5%), 28.2% (n=29) earned $60,001-$80,000, and 19.4% (n=20) earned more than $80,001.

About half of the technology-dependent children (n=51, 49.5%) had a primary diagnosis that was due to a genetic disorder, and 27.1% (n=28) were born preterm (≤36 weeks gestation). The children’s mean age was 6.58 years (range 7 months-16.6 years), with 47.6% age 5 years or less. Each child’s primary diagnosis (the diagnosis that precipitated the child’s dependence on technology), was determined by chart review. The most common diagnoses were related to neuromuscular (43.7%) or respiratory conditions (22.3%). Gastrointestinal conditions were the primary diagnoses for 16.5% of children, and other less common primary diagnoses included cardiac conditions, cystic fibrosis, metabolic disorders, and renal disorders. A majority of the children (73.8%) were categorized as OTA Group 3 (respiratory/nutritional support), 17.5% as Group 1 (mechanical ventilation), and 8.7% as Group 2 (intravenous medications/nutritional support). Almost all (88.7%) of the children had a feeding tube. Other frequently required technologies included a tracheostomy tube (31.1%) or supplemental oxygen (42.7%). Over half (50.5%) of the children required two or more types of technology.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

Functional status scores on the FS II-R ranged from 11-28 (M=21.47, SD=4.03). Higher scores indicated better function, with a maximum possible score of 28. Approximately 13% (n=13) of the children had very good function (26 or above) and over half (55.3%, n=57) had fairly good function (21-25), while approximately 32% (n=33) had fair to poor function (20 or below). The duration of caregiving, the period of time the mother had cared for the child since he/she was discharged from the hospital dependent on technology, ranged from 2 months-13.4 years (M=4.76 years, SD=3.74 years). The children received on average 41.23 hours of home nursing per week (range 0-144); however, 36.8% did not receive any home nursing, while 42.7% received over 41 hours per week. Scores for depressive symptoms on the CES-D ranged from 0-54 (M=14.07, SD=11.05) with a maximum possible score of 60; 39% scored ≥16, indicating high risk for clinical depression. The range of scores for normalization were 45-900 (M=385.89, SD=190.5) from a possible range of 0-1000. Using the FFFS, family functioning scores ranged from 0-114 (M=35.25, SD=20.58), and the possible range was 0-150.

Differences Based on Level of Technology Dependence

ANOVA analyses were conducted using the F test for each of the dependent variables. Family functioning (F= 1.589, p= .208), normalization (F= 1.749, p= .362), and depressive symptoms (F= .377, p= .687) were all found to be not significant. Therefore, there were no significant differences between the levels of technology dependence (OTA Groups 1-3) for family functioning, normalization efforts, and depressive symptoms.

Family Functioning

Using HMR analysis, family functioning was regressed on mother’s depressive symptoms, child’s severity of illness (functional status and level of technology dependence) and normalization efforts (Table 1, Model A). In HMR step one, mother’s depressive symptoms, child’s severity of illness, and normalization accounted for 36.3% of the adjusted variance in family functioning and achieved statistical significance (F= 12.172, p<.001). The only independent variable in the regression equation noted to be significant was depressive symptoms (β= .56, p=<.001). After all covariates (length of caregiving duration, amount of home healthcare nursing hours, race, family income, and child’s age) were added in step two (Table 1, Model B), the adjusted variance decreased slightly, to 34.9% but remained statistically significant. Depressive symptoms continued to be the only significant variable; greater depressive symptoms were related to poorer family functioning.

Table 1.

Summary of Regression Analysis for Family Functioning (N=99)

| Predictor Variable | Model A | Model B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | B | β | |

| Constant | 22.974 | 19.636 | ||

| Normalization | -.010 | -.094 | -.015 | -.136 |

| Functional Status | -.001 | .000 | .115 | .022 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 1.057 | .560*** | 1.103 | .585*** |

| Tech. Dependent: Ventilator | 4.259 | .078 | 5.774 | .105 |

| Tech. Dependent: IV | 6.274 | .087 | 7.211 | .100 |

| Race | -4.826 | -.100 | ||

| Age of Child | .059 | .150 | ||

| Duration of Caregiving | -.060 | -.132 | ||

| Home Healthcare Nursing | -.001 | -.003 | ||

| Family Income | 1.867 | .120 | ||

| R2 | .396 | .415 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | .363 | .349 | ||

| F | 12.172*** | 6.243*** | ||

p < .001

Mediating Effects of Depressive Symptoms and Normalization

Using tests for mediation effect as described by Baron and Kenny (1986), depressive symptoms partially mediated between the child’s functional status and normalization; consequently, better function contributed to increased normalization efforts. Depressive symptoms were not a mediator between functional status and family functioning. Additionally, normalization was not found to be a mediator between a child’s functional status and family functioning or depressive symptoms and family functioning.

Normalization

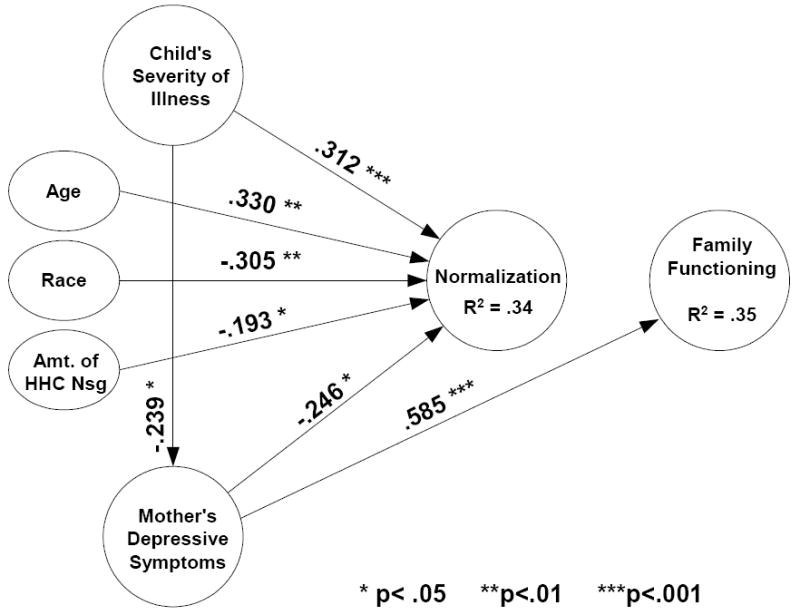

Using HMR analysis, normalization was regressed on the mother’s depressive symptoms, child’s severity of illness (functional status, level of technology dependence), and family functioning in step one of the model. As shown in Table 2, Model A, depressive symptoms, child’s functional status and family functioning accounted for 24.6% of the adjusted variance in normalization and achieved statistical significance. Two independent variables in the HMR analysis were significant: depressive symptoms (β= -.289, p=<.05) and functional status of the child (β= .275, p=<.01). After all covariates (length of caregiving duration, amount of home healthcare nursing hours, race, family income and child’s age) were included in the model (Table 2, Model B), the adjusted variance of the HMR model increased to 34.3%. Depressive symptoms and functional status remained significant variables in the equation. Three covariates added to the explained variance (Table 2, Model B): amount of home healthcare nursing (β= -.193, p= <.05), child’s age (β= .330, p= <.01), and race (β= -.305, p= .001). The variables that were significantly related with greater normalization efforts include better functional status, fewer depressive symptoms, being non-Caucasian or of Hispanic ethnicity, less home nursing hours, and an older child.

Table 2.

Summary of Regression Analysis for Normalization (N=99)

| Predictor Variable | Model A | Model B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | B | β | |

| Constant | 224.801 | 240.903 | ||

| Family Functioning | -1.013 | -.112 | -1.242 | -.137 |

| Functional Status | 12.928 | .275** | 14.629 | .312*** |

| Depressive Symptoms | -4.944 | -.289* | -4.204 | -.246* |

| Tech. Dependent: Ventilator | -31.183 | -.063 | 16.070 | .034 |

| Tech. Dependent: IV | -66.959 | -.103 | -87.049 | -.134 |

| Race | -133.185 | -.305** | ||

| Age of Child | 1.177 | .330** | ||

| Duration of Caregiving | -.511 | -.122 | ||

| Home Healthcare Nursing | -.825 | -.193* | ||

| Family Income | 4.917 | .035 | ||

| R2 | .284 | .410 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | .246 | .343 | ||

| F | 7.381*** | 6.111*** | ||

p< .05

p< .01

p < .001

Discussion

Results from the ANOVA analyses indicated there were no statistical differences in normalization efforts, family functioning, and mothers’ depressive symptoms based on the child’s level of technology dependence (OTA, 1987 Groups 1-3). These findings are consistent with previous studies (Fleming et al., 1994; Leonard et al., 1993); however, an improved methodology for technology group assignment may help distinguish significant differences in these groups in the future.

Depressive Symptoms: The Sole Predictor of Family Functioning

Findings from this study indicate that mothers of technology-dependent children are at high risk for clinical depression that can affect overall family functioning. A mother’s depressive symptoms was the only significant predictor of family functioning while controlling for covariates in HMR analysis and accounted for 34.9% of variance in family functioning, underscoring the impact of such symptoms. Additionally, greater depressive symptoms and less normalization efforts were significantly correlated with poorer family functioning.

In this study, 39.8% of the mothers, or double the general population rate, scored ≥16 on the CES-D, indicating an increased risk for clinical depression (Radloff, 1977). This finding is consistent with other studies, where up to 45% of mothers of technology-dependent children scored >16 on the CES-D (Kuster & Badr, 2006; Miles et al., 1999). Furthermore, 23.3% of the mothers in the present study scored ≥23, indicating a very high risk for clinical depression (Myers & Weissman, 1980). These findings strongly suggest that managing the demanding care regimens and coordinating the many services typically required by technology-dependent children while still maintaining a normal family life is difficult for many of their mothers. Therefore, an intervention that targets these mothers’ depressive symptoms is recommended.

This study’s finding regarding a strong relationship between depressive symptoms and family functioning is consistent with previous research (Frankel & Wamboldt, 1998; Ireys & Silver, 1996; Kuster & Badr, 2006) that indicates a decreased satisfaction with family relationships, an indicator of family functioning, is significantly related to greater depressive symptoms (Weiss & Chen, 2002). Frankel and Wamboldt (1998) propose that how a child’s illness interferes with and impacts a family is determined by the psychological health of the primary parent caretaker. The psychological health of the parent caretaker is in turn affected by family functioning and the child’s functional status. Therefore, a mother’s psychological state, particularly the amount of depressive symptoms, plays a significant role in how a family with a technology-dependent child functions.

Study participants indicated that the availability and financial resources for mental health support services are sorely lacking. Many stated that when a mental health provider was found, the provider was overwhelmed by the magnitude of the situation and was of little assistance or guidance. Some of the participants lacked financial resources to continue attending mental healthcare sessions. Furthermore, these mothers had limited time or respite care for their technology-dependent children to attend such sessions. Therefore, referral to mental healthcare providers who are familiar with the complex situations these mothers face, and would provide flexibility of time and location for counseling sessions, would greatly benefit this population.

The findings related to normalization are important empirical evidence because this was the first time that normalization has been quantitatively analyzed to determine predictors. HMR analysis of normalization (Table 2, Model A) revealed that more depressive symptoms and a poorer functional status of the child explained about 25% of the variance in normalization. Past qualitative research is consistent with the current study findings of the relationship between severity of illness and normalization (Dashiff, 1993; Knafl & Deatrick, 2002). Additionally, three covariates were significantly related in the HMR and added to the explained variance (Table 2, Model B); less home health care nursing, older child, and mothers identified as Non-Caucasian race or Hispanic ethnicity, all of which contributed significantly to greater normalization efforts. Therefore, one plausible explanation is that those children with poor functional status and complex care needs require more home nursing hours that influence a families’ normalization efforts. An alternate explanation is that increased nursing presence in the home is disruptive to the family routine and limits the amount of normalization efforts (O’Brien & Wegner, 2002).

Statistical analyses for mediation (Baron & Kenney, 1986) reveal that depressive symptoms are a partial mediator between a child’s functional status and normalization. No previous mediation testing has been conducted with these concepts; however, a significant link has been identified between functional status and a parent’s depressive symptoms (Frankel & Wamboldt, 1998; Weiss & Chen, 2002), as well as severity of illness and normalization efforts (Cohen, 1993; Knafl & Deatrick, 2002; O’Brien, 2001).

Findings from the current study help to validate the proposed conceptual model (Figure 2). HMR analysis results indicate that a mother’s level of depressive symptoms was the only significant predictor of family functioning. The mother’s depressive symptoms, child’s functional status, amount of home healthcare nursing, race/ethnicity, and child’s age were significant predictors of normalization efforts. The mother’s depressive symptoms were found to be a mediator between the child’s severity of illness and normalization. Therefore, the current study supported the majority of the study model. However, a direct relationship between the study variables, normalization and severity of illness and family functioning, was not supported.

Figure 2.

Study Model for Normalization and Family Functioning in Families with a Child who is Technology-dependent

Limitations

The convenience sample of 103 mothers primarily from Northeast Ohio who care for their technology-dependent children at home may limit generalization of the findings to other more diverse populations. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevents inferences regarding causality.

Clinical Practice and Policy Implications

Nurses play a key role in helping to enhance normalization efforts and promote positive family functioning. The following predischarge educational components are of paramount importance: 1) organizational tools such as charts or notebooks for the numerous treatments, therapies, and appointments,; 2) strategies for delivery of safe care and treatments, while maintaining flexibility to allow for as normal a family life as possible; and 3) strategies for transporting the children and their equipment and supplies to appointments or other activities.

Current policy regarding resource allocation needs to be reexamined to help families continue to care for their technology-dependent children at home. These resources include family mental health support systems that need to be put in place prior to the child’s discharge home. As evidenced by the high level of depressive symptoms experienced by nearly 40% of this study’s participants, caring for these children is a formidable task, especially given the limited supports that are currently available. Supports such as preventive, predischarge mental health screening and treatment, as well as ongoing mental health screening and treatment, are essential. Past research indicates that maintaining the mental health of caregivers and family functioning positively affects the child’s growth and development (Miles et al., 1999). Such preventive support and/or treatment may help to avoid mental health crises that would negatively affect family functioning and the health of the child and potentially lead to the child’s readmission to the hospital.

The need for a qualified respite care system for these families is apparent. Almost half of the families did not receive any nursing care at home. Many indicated it was difficult to find adequately prepared nurses to care for their children’s complex needs. Programs to familiarize home healthcare nurses with the advanced technology needs and the concerns of this special population of children and their families would greatly assist the comfort level of nurses and families alike (Boroughs & Dougherty, 2009).

This study of 103 mothers of technology-dependent children provides evidence to assist families caring for this vulnerable and growing population of children at home. Findings include evidence that mothers of technology-dependent children are at high risk for clinical depression, which can affect overall family functioning. A mother’s depressive symptoms was the only significant predictor of family functioning. Resources such as predischarge education, respite care, and mental health support would enhance normalization efforts and promote positive family functioning, thereby bolstering the children’s optimal growth and development. An intervention that will reduce the psychological distress experienced by mothers of technology-dependent children is an important first step in this process.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Alpha Mu Chapter of Sigma Theta Tau International, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing Alumni Association, Case Western Reserve University Research ShowCASE, and the Society of Pediatric Nurses. This study was supported by grant UL 1RR024989, the Clinical and Translational Collaborative at Case Western Reserve University, Dahms Clinical Research Unit. The first author is supported by a NIH/NINR T32-NR009761 Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Contributor Information

Valerie Boebel Toly, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Ave. Cleveland, OH 44106, vab@case.edu, (216) 368-3082 office, (216) 368-3542 fax.

Carol M. Musil, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH.

John C. Carl, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, Head, Section of Pediatric Pulmonology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH.

References

- Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroughs D, Dougherty JA. Care of technology-dependent children in the home. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2009;27(1):37–42. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000343784.88852.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher P, Whitmire JT, Brunssen S, Kluttz-Hile C. Children who are medically fragile in North Carolina: Using Medicaid data to estimate prevalence and medial care costs in 2004. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2006;10:461–466. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale FA, Alexander E, Davis M, Rennick J, Troini R. Daily living with distress and enrichment: The moral experience of families with ventilator-assisted children at home. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):e48–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clawson JA. A child with chronic illness and the process of family adaptation. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1996;11(1):52–61. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(96)80038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MH. The unknown and the unknowable--managing sustained uncertainty. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1993;15(1):77–96. doi: 10.1177/019394599301500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MH. The technology-dependent child and the socially marginalized family: A provisional framework. Qualitative Health Research. 1999;9(5):654–668. doi: 10.1177/104973299129122144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashiff CJ. Parents’ perceptions of diabetes in adolescent daughters and its impact on the family. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1993;8(6):361–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatrick JA, Knafl KA, Murphy-Moore C. Clarifying the concept of normalization. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1999;31(3):209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatrick JA, Thibodeaux AG, Mooney K, Schmus C, Pollack R, Davey BH. Family management style framework: A new tool with potential to assess families who have children with brain tumors. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2006;23(1):19–27. doi: 10.1177/1043454205283574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J, Challela M, Eland J, Hornick R, Johnson P, Martinson I, Nativio D, Nokes K, Riddle I, Steele N, et al. Impact on the family of children who are technology-dependent and cared for in the home. Pediatric Nursing. 1994;20(4):379–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel K, Wamboldt MZ. Chronic childhood illness and maternal mental health--why should we care? The Journal of Asthma. 1998;35(8):621–630. doi: 10.3109/02770909809048964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning C, Kirk S, Guiffrida A, Lawton D. Technology-dependent children in the community: Definitions, numbers and costs. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2001;27(4):321–334. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer B, MacDorman MF, Martin JA, Peters KD, Strobino DM. Annual summary of vital statistics-1997. Pediatrics. 1998;102(6):1333–1349. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase JE, Rostad M. Experiences of completing cancer therapy: Children’s perspectives. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1994;21(9):1483–1492. discussion 1493-1484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman MB, Harmatz P, Acree M, Wilson L, Moskowitz JT, Ferrando S, Folkman S. Economic and psychologic costs for maternal caregivers of gastrostomy-dependent children. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;145(4):511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireys HT, Silver EJ. Perception of the impact of a child’s chronic illness: Does it predict maternal mental health? Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1996;17(2):77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Allen P. The primary care provider and children with chronic conditions. In: Jackson Allen P, Vessey JA, editors. Primary care of the child with a chronic condition. 4. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2004. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk S, Glendinning C. Developing services to support parents caring for a technology-dependent child at home. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2004;30(3):209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00393.x. discussion 219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Breitmayer B, Gallo A, Zoeller L. Family response to childhood chronic illness: Description of management styles. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1996;11(5):315–326. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(05)80065-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J. The challenge of normalization for families of children with chronic conditions. Pediatric Nursing. 2002;28(1):49–53. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J. Further refinement of the family management style framework. Journal of Family Nursing. 2003;9:232–256. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Zoeller L. Childhood chronic illness: A comparison of mothers’ and fathers’ experiences. Journal of Family Nursing. 2000;6:287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kuster PA, Badr LK. Factors influencing health promoting activities of mothers caring for ventilator-assisted children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2006;19(4):276–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard BJ, Brust JD, Nelson RP. Parental distress: Caring for medically fragile children at home. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1993;8(1):22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan EA, Youngblut J, Haruzivishe C. Pediatric home healthcare: Patients and providers. Home Healthcare Nurse. 1999;17(11):699–705. doi: 10.1097/00004045-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D, Burchinal P, Nelson D. Distress and growth outcomes in mothers of medically fragile infants. Nursing Research. 1999;48(3):129–140. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy F. Relationship between family use of normalization and psychosocial adjustment in children with chronic physical disorders. Unpublished master’s thesis. McGill University; Montreal, Quebec, Canada: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy F, Gottlieb L. Normalization scale. 1992 Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KE. Parenting a technology assisted infant: Coping with occupational stress. Social Work in Health Care. 1997;24(3-4):113–126. doi: 10.1300/J010v24n03_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J, Weissman M. Use of a self-report symptom scale to detect depression in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137:1081–1083. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newacheck PW, Kim SE. A national profile of health care utilization and expenditures for children with special health care needs. Archives in Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(1):10–17. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien ME. Living in a house of cards: Family experiences with long-term childhood technology dependence. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2001;16(1):13–22. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2001.20548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien ME, Wegner CB. Rearing the child who is technology-dependent: Perceptions of parents and home care nurses. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2002;7(1):7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2002.tb00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Technology Assessment. Technology-dependent children: Hospital care vs. home care: A technical memorandum: Congress of the United States 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Ostwald SK, Leonard B, Choi T, Keenan J, Hepburn K, Aroskar MA. Caregivers of frail elderly and medically fragile children: Perceptions of ability to continue to provide home health care. Home Health Care Service Quarterly. 1993;14(1):55–80. doi: 10.1300/J027v14n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson B. The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2001;33:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The ces-d scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm RS, Bradley JF. Normalization in families raising a child who is medically fragile/technology-dependent and developmentally delayed. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(6):807–820. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CS, Feetham SL. Assessing family functioning across three areas of relationships. Nursing Research. 1982;31(4):231–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RE, Jessop DJ. Functional status ii(r). A measure of child health status. Medical Care. 1990;28(11):1041–1055. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Teague BR, Fleming JW, Castle A, Kiernan BS, Lobo ML, Riggs S, Wolfe JG. “High-tech” home care for children with chronic health conditions: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1993;8(4):226–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toly V. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Case Western Reserve University; Cleveland, OH: 2009. Normalization and family functioning in families with a child who is technology-dependent. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SJ, Chen JL. Factors influencing maternal mental health and family functioning during the low birthweight infant’s first year of life. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2002;17(2):114–125. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2002.124129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, Morse JM, Penrod J. Absolute involvement: The experience of mothers of ventilator-dependent children. Health and Social Care in the Community. 1998;6(4):224–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.1998.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski J, Wykle M. Racial differences in self-assessed health problems, depressive cognitions, and learned resourcefulness. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association. 1994;7:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]