Abstract

In vivo fluorescent labeling of an expressed protein has enabled the observation of its stability and aggregation directly in bacterial cells. Mammalian cellular retinoic acid-binding protein I (CRABP I) was mutated to incorporate in a surface-exposed omega loop the sequence Cys-Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys-Cys, which binds specifically to a biarsenical fluorescein dye (FlAsH). Unfolding of labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I is accompanied by enhancement of FlAsH fluorescence, which made it possible to determine the free energy of unfolding of this protein by urea titration in cells and to follow in real time the formation of inclusion bodies by a slow-folding, aggregationprone mutant (FlAsH-labeled P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I). Aggregation in vivo displayed a concentration-dependent apparent lag time similar to observations of protein aggregation in purified in vitro model systems.

Keywords: protein aggregation, protein folding, fluorescence

Protein folding is an exquisitely optimized process that normally succeeds in producing functional molecules in vivo, despite physicochemical conditions that are very challenging. The heteropolymeric nature of the polypeptide chain encodes a great diversity of complex architectures of native proteins but also presents many side chain groups that are marginally soluble in aqueous solution. Not surprisingly, aggregation of newly synthesized proteins emerges as a process that competes with folding in vivo. In bacterial cells, aggregation of partially folded intermediates manifests itself in the production of insoluble inclusion bodies and often occurs when an exogenous protein is overexpressed (1). Several human diseases, including Alzheimer's, Huntington's, and spongiform encephalopathies, are characterized by the formation of insoluble protein aggregates (2). These distinctive aggregated states seem to be formed from partially folded, partially unfolded, or other nonnative intermediates and not from the native state. Thus, considerable research has been dedicated to the goal of achieving a fundamental understanding of protein aggregation, and much progress has been achieved in several systems in vitro (3). By contrast, relatively little is known about how this process occurs in vivo. Complicating research on protein folding and aggregation in vivo is the need to study these processes in the complex and concentrated environment of the cell. It is therefore highly desirable to develop methods to observe the fates of proteins directly in cells, including their thermodynamic stabilities, their kinetics of folding, the nature of folding intermediates and the energy landscape of folding, and the effects of mutations. Here, we have taken advantage of new approaches to labeling protein molecules in the cell with fluorescent dyes (4) to monitor the synthesis, folding, and aggregation of a protein whose in vitro folding has been well characterized.

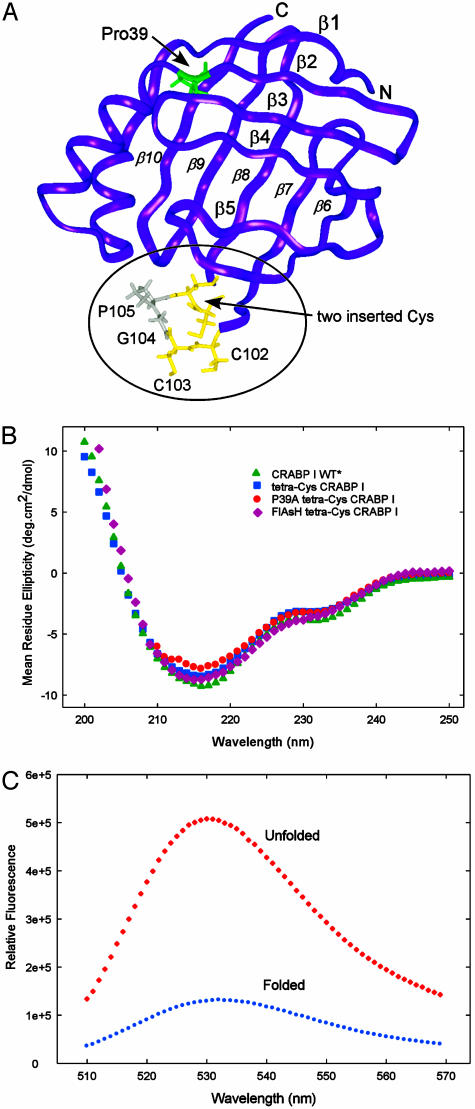

Cellular retinoic acid-binding protein I (CRABP I) is a 136-residue member of the large family of intracellular lipid-binding proteins, which fold into β-barrel structures (Fig. 1A) (5). Our studies of CRABP I have demonstrated that its in vitro landscape of folding is rugged, with three well defined kinetic phases. An initial hydrophobic collapse (≈300 μs) is accompanied by formation of considerable secondary structure (6, ¶). In 100 ms, native topology develops including the appearance of a ligand-binding cavity (8). The bulk of the protein molecules form stably hydrogen-bonded native structure in a 1-s kinetic phase (6, ¶). Some regions of CRABP I adopt native-like structure as isolated peptides [the helical segment (9) and turns 3 and 4 (10)], suggesting locally encoded structure. A conserved network of hydrophobic interactions links strands in the barrel, primarily in the N-terminal β-sheet (11). One question suggested by these in vitro results is how off-pathway aggregation events are avoided in this predominantly β-sheet protein. Moreover, the rate of synthesis in Escherichia coli [≈15 peptide bonds per second (12)] is slower than the rate of folding observed in vitro, leaving open the possibility that CRABP I folds cotranslationally during its biosynthesis.

Fig. 1.

(A) Backbone structure of CRABP I (rendered by using insight II from PBD file 1CBI) showing the point of insertion of the tetra-Cys motif between strands β7 and β8 in the omega loop (circled) and the location of P39, at the end of the second α-helix. (B) CD spectra comparing CRABP I WT*, tetra-Cys CRABP I, P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I, and FlAsH-labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I. (C) fluorescence of FlAsH-labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I (excitation 500 nm) in its native folded state and denatured by 8 M urea (unfolded), showing the hyperfluorescence of the unfolded state.

Our approach to studying CRABP I in vivo has exploited a recently described fluorescein analogue containing two arsenoxides (FlAsH) that ligates specifically in vivo to Cys-Cys-X-X-Cys-Cys motifs incorporated by mutagenesis into expressed proteins (4, 13). The unliganded dye does not fluoresce, and binding conditions are chosen so that four Cys sulfhydryls are necessary for high-affinity binding. The likelihood of adventitious binding to endogenous, unmutated protein is thus extremely low. By incorporating this motif into CRABP I at an internal loop, we have engineered a dye-binding site that reports on the state of folding of this protein in vivo. We used dye fluorescence to monitor the time course of CRABP I expression following induction and compared the behavior of the wild-type protein and a slow-folding, aggregation-prone mutant (both engineered to contain the dye-binding site). Dye fluorescence also was used to follow urea denaturation of the expressed proteins in E. coli cells. Intriguingly, we observe that the free energy difference between the folded and unfolded states is similar in vivo to that measured in vitro, but the transition is more strongly dependent on urea concentration, suggesting mechanistic differences between the crowded cellular environment and the high-dilution, test tube experiment. Furthermore, we are able to monitor the time course of aggregation in vivo for the slow-folding mutant, and we see that this process shows an apparent concentration-dependent lag phase reminiscent of that observed in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Construction of tetra-Cys CRABP I. CRABP I pseudo-wild type (with a stabilizing mutation, R131Q, and a His-tag for purification) cloned in the pET16b vector (6) was used as a template DNA to introduce a tetra-cysteine motif into the omega-loop based on the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene). In three successive mutational steps, Gly-102 and Asp-103 were replaced by cysteines, and in parallel two cysteines were inserted between Pro-105 and Lys-106, yielding the FlAsH-binding Cys-Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys-Cys motif. Tetra-Cys CRABP I DNA was used as a template in the amino acid substitution of P39A yielding the tetra-Cys P39A CRABP I mutant. The introduced mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Protein Expression and Purification. E. coli BL21(DE3) was used as an expression host. Cells bearing the plasmids encoding tetraCys CRABP I and tetra-Cys P39A CRABP I were cultivated at 37°C in LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) as a selection marker. Protein expression was induced with 0.4 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) for 4 h. Tetra-Cys CRABP I and tetra-Cys P39A CRABP I, expressed as N-terminally His-tagged proteins, were purified from the soluble cell extract on an Ni-NTA column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Following elution with a linear gradient of imidazole (20–500 mM) (6), the protein fractions were dialyzed gradually in 10 mM and 1 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 8.0; containing 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). For the tetra-Cys P39A CRABP I mutant, protein was isolated from both the soluble and insoluble fractions of the cell lysates (6).

Circular Dichroism. Far-UV CD spectra were collected on a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter. Samples were 10 μM in protein, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, with 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol.

Cell Fractionation. Ten-milliliter aliquots of P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I-expressing cells at 37°C were harvested and resuspended in 1.5 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 8.0, containing 300 mM NaCl. After lysis and sonication (3 min, 30% duty cycle), the cell homogenate was separated into soluble and insoluble fractions by centrifugation at 27,000 × g for 30 min. The insoluble pellet was solubilized in 1.5 ml of buffer containing 8 M urea, 5 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl (pH 7.5). Both fractions were analyzed by SDS/PAGE (12.5%), and the CRABP I content in each fraction was quantified by optical densitometry (Bio-Rad).

In Vitro Labeling with FlAsH-Ethanedithiol (EDT2). The labeling of the purified tetra-Cys CRABP I and tetra-Cys P39A CRABP I with FlAsH-EDT2 was accomplished following the manufacturer's instructions (PanVera, Madison, WI). Namely, the protein stock solution (50 μM in 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, containing 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) was equilibrated at room temperature for at least 6 h to reduce any disulfide bonds. Then, 4 μl were mixed with 144.5 μl of 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5 (containing 1 mM tris(carboxyethyl)phosphine and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and labeled with 1.5 μl of 0.1 M FlAsH-EDT2 for 2 h at room temperature. The labeled complex was stable for several days at 4°C. Labeled protein could be reversibly unfolded and refolded with retention of spectroscopic properties, consistent with the reported high stability of the FlAsH–tetraCys complex (14).

FlAsH-EDT2 Labeling in Cells. The E. coli BL21(DE3) cells expressing tetra-Cys CRABP I or tetra-Cys P39A CRABP I mutant proteins, cultivated in LB medium up to an OD600 of 0.5 and pretreated with lysozyme (50 ng/ml, 10 min on ice) to make the outer membrane permeable to dye, were washed, resuspended in LB, and preloaded with FlAsH-EDT2 and EDT to suppress the labeling of endogenous cysteine pairs (13, 14). Final concentrations of FlAsH-EDT2 were from 150 μM to 1 mM, and EDT from 150 μM to 1.6 mM, with little to no impact on the results. (The potential deleterious effects of the lysozyme treatment were checked by comparing viability and growth of treated versus untreated cells. After less than one generation, the treated cells behaved the same as untreated.) At OD600 = 1, IPTG was added to 0.4 mM to induce protein synthesis; 150-μl cell aliquots were withdrawn at different times postinduction, rinsed, resuspended in 150 μl of 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), and subjected to fluorescence measurements. In experiments designed to reduce total protein concentration in the cells, protein synthesis was retarded by addition of 2.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol (15) added simultaneously with the induction of protein expression. In the time-course experiments, the rinsing steps were omitted, and the background from a negative control of CRABP I wild-type expressing cells preloaded with FlAsH-EDT2 was subtracted. No toxic effects of the FlAsH dye were seen under our experimental conditions, based on the viability of the cells on agar plates, as well as by normal appearance of growth curves of liquid cultures.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy and Microscopy. Fluorescence spectra were measured in a quartz cuvette on a Photon Technology International QM-1 fluorometer. The temperature of the cuvette holder was maintained at 37°C with a water bath. Excitation was at 500 nm (2-nm bandwidth), and emission was monitored from 510 to 580 nm (2-nm bandwidth). Three transients were averaged at each wavelength interval. Repeat experiments on different days were used to determine errors. Protein concentration was typically 3 μM unless otherwise stated. For fluorescence microscopy studies, 2 μl of 10-fold concentrated cell suspension in 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5) were immobilized in 1% agarose in LB and imaged by using a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope, with excitation at 485 nm and a 510-nm emission barrier filter; the processing software used was openlabs (Improvision, Lexington, MA).

Stability Experiments. To cultures prelabeled with FlAsH-EDT2, as described above, urea in 10 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.5) was added 2 h after IPTG induction of protein expression to various final concentrations, and the incubation was continued at 37°C for 30 min (to minimize loss of viability). Culture solution (150 μl) was pelleted and washed in 50 mM Hepes buffer (pH 7.5) and then subjected to fluorescence measurements. Three transients were averaged at each wavelength interval. Five-microliter cell suspensions at each urea concentration were plated on LB-agar plates and incubated overnight at 37°C to assess cell viability. In the in vitro urea melting experiments, 3 μM protein prelabeled with FlAsH-EDT2 was equilibrated at different urea concentrations overnight at 37°C before fluorescence measurements, following our standard protocol, although incubation times could be substantially shorter at this temperature, and the unfolding transition was monitored by either Trp or FlAsH fluorescence or by CD. The actual urea concentration was determined by measuring the index of refraction (16). Urea denaturation curves were analyzed by using the linear extrapolation method, with curve fitting according to procedures described by Fersht (17).

Results and Discussion

A CRABP I Mutant with an Internal FlAsH Binding Site. We reasoned that a dye-binding site internal to the protein might interact with the dye in a manner that reports on the structure of the protein (i.e., whether it was folded in its native structure or not). The original design of the FlAsH dye suggested that presentation of this sequence in an α-helical conformation would be optimal for dye binding (13), but more recent peptide work showed that the tendency of the X-X residues to adopt a hairpin turn favors dye binding (14). The lowest sequence conservation among the iLBP family members is observed in the omega loop between strands 5 and 6 (11). Consequently, a dye-binding site was created by insertion of two cysteine residues (after residues Gly-104–Pro-105 and before Lys-106), and by mutation of Gly-102–Asp-103 to Cys-Cys (15). Thus, the motif Cys-Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys-Cys is presented internally within this tetra-Cys mutant protein with minimal sequence alteration (Fig. 1 A). The Cys-Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys-Cys sequence is able to bind FlAsH according to peptide studies but in fact it is not the optimal sequence; Cys-Cys-Pro-Gly-Cys-Cys is significantly better based on peptide results (14). However, we elected to retain the Gly-Pro that is part of the CRABP I sequence (residues 104–105). The CRABP I construct we used for all of this work harbors a mutation (R131Q) that was previously found to stabilize the protein significantly (16) while not perturbing its folding behavior (6). The same dye-binding site was also introduced into a mutant of CRABP I, P39A, which folds and unfolds slowly in vitro (18) and shows a tendency to form inclusion bodies in vivo. P39 serves as a helix-stop signal, and we have suggested that its substitution by alanine stabilizes an intermediate with an extended nonnative helix (18).

In their native states, both tetra-Cys CRABP I (19) and P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I take up a structure that is indistinguishable from that of the wild type based on far-UV circular dichroism (Fig. 1B), and both retain retinoic acid binding activity (data not shown). Introducing the tetra-Cys mutation caused very little change in equilibrium stability of CRABP I, based on urea titrations monitored by Trp fluorescence or CD; ΔG° between the native and unfolded states is 3.6 kcal/mol for tetra-Cys CRABP I [the slope in the transition region, or m value (16, 17), was 2.2 kcal/mol·M], 3.6 kcal/mol for P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I (m = 2.2 kcal/mol·M), as compared to 4.2 kcal/mol (m = 2.0 kcal/mol·M) for the original CRABP I protein (data not shown). Both unfolded and folded forms of these proteins bind the FlAsH dye, and there is no change in equilibrium stability of the labeled protein with respect to the unlabeled as assessed by urea titrations using Trp fluorescence or CD. Interestingly, curvefitting in vitro urea melts monitored by following FlAsH fluorescence yielded smaller ΔG° and m values (2.5 kcal/mol and 1.3 kcal/mol·M, respectively) (data shown in Fig. 2B). The most likely explanation for this difference is that the transition probed by the FlAsH dye is not fully two-state and, instead, reports on a partial local unfolding as well as the global melt. Measurement of unfolding kinetics of the labeled or unlabeled tetra-Cys CRABP I proteins yielded a 2-fold faster rate (single exponential; data not shown) than for the original CRABP I, which is consistent with the observed change in native-state stability and argues for minimal perturbation of the folding properties of these proteins from introduction of the tetra-Cys motif or from labeling with FlAsH. In contrast with our expectations, the unfolded proteins display higher fluorescence than the folded (Fig. 1C). Although the origin of the differential quantum yields of the FlAsH dye in the two states of the proteins is not clear, it seems likely that the environment of the fluorophore in the folded protein brings a quenching residue into proximity and that the quencher is more distant in the unfolded protein. Studies are in progress to explore the specific interactions responsible.

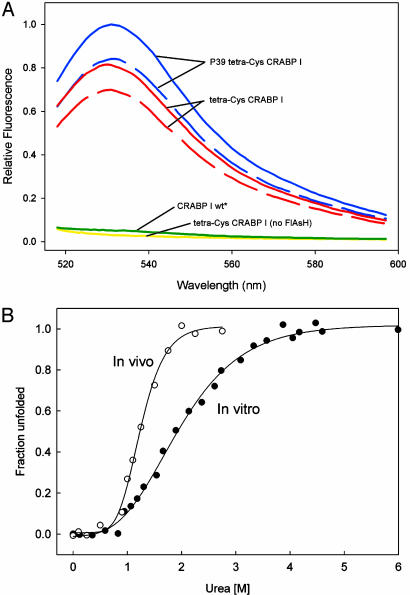

Fig. 2.

(A) FlAsH labeling of tetra-Cys CRABP I and P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I in E. coli cells. Before IPTG induction of protein expression, cells were treated with dye, either after lysozyme pretreatment (solid lines) or not (dashed lines). Spectra shown were obtained 4 h after induction. (B) Urea denaturation curves monitored using fluorescence of FlAsH-labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I (excitation 500 nm, emission 530). For the in vivo curve, urea was added to the indicated concentration 2 h after induction of protein expression in cells preloaded with FlAsH.

FlAsH Fluorescence Enables Stability of CRABP I in Vivo to be Monitored. Efficient labeling of expressed protein in E. coli cells was accomplished by gentle lysozyme pretreatment to enhance membrane permeability and immediate preloading of the permeabilized cells with FlAsH-EDT2 at a concentration high enough to saturate the newly synthesized tetra-Cys CRABP I at maximal expression on induction with IPTG (Fig. 2 A). Under these conditions, it was possible in principle to assess the in vivo stability of FlAsH-labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I.

E. coli cells preincubated with dye and expressing tetra-Cys CRABP I were treated after2hwith increasing concentrations of the denaturant urea at 37°C, and fluorescence was monitored at 530 nm (Fig. 2B). Controls showed that the cells retained viability up to ≈3 M urea, as had been reported in a recent mass spectrometry-based in vivo stability measurement (20). The resulting sigmoidal curve can be directly compared with that obtained in vitro (Fig. 2B) and used to measure the free energy stabilizing the labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I in vivo. The stability derived from following FlAsH fluorescence during urea denaturation in cells is quite similar to that measured by the same spectroscopic observation in vitro (ΔG° = 2.7 kcal/mol in vivo versus 2.5 kcal/mol in vitro), but the transition is more strongly urea dependent, manifested by a significantly higher slope through the transition region (m = 2.1 kcal/mol·M in vivo versus 1.3 kcal/mol·M in vitro). This latter observation is inconsistent with the expected effect of macromolecular crowding in vivo, which might have been predicted to cause greater collapse of the unfolded state (21) and thus a smaller surface area change on unfolding, which has been shown to be directly related to the m value (22). On the other hand, our in vitro observations suggested that the FlAsH dye reports on partial local unfolding as well as the global melt, and the in vivo curve could reflect a more cooperative loss of structure. It is tempting to speculate that molecular chaperones may lead to more cooperative unfolding of the expressed proteins in vivo by binding to any exposed hydrophobic surfaces, thus altering the mechanism of unfolding with respect to that observed in vitro. The complexity of the influence of urea on the cellular contents must be considered, in any case, when interpreting in vivo stability measured by addition of denaturant. Many cellular proteins and complexes may be undergoing structural destabilization under the influence of urea, in addition to the one observed, and thus the viscosity and interactions within the cell are not constant. Here, we must also be attentive to the complexities of the reported signal. Therefore, the in vivo stability results should be interpreted cautiously.

FlAsH Fluorescence Reports on Expression, Folding, and Inclusion Body Formation of CRABP I and an Aggregation-Prone Mutant in Vivo. Observing the time course of FlAsH fluorescence from labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I in cells offers exciting prospects for following its cellular fate. Fluorescence at 530 nm was monitored after preloading of E. coli cells with dye and induction of protein synthesis with IPTG. A steady increase in the fluorescence from labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I was observed over 150–200 min, after which point the fluorescence plateaued; cell density showed that the plateau coincided with the end of log phase growth of the bacteria (Fig. 3A, red lines). Dye labeling is rapid in the cell (4, 13), ample dye is available on induction, and dye continues to enter the cells from the bulk (albeit more slowly after the cells recover from the initial lysozyme pretreatment). Dye binding to the tetra-Cys motif is expected to occur as soon as this sequence is accessible to the aqueous reagent in the cytoplasm. Therefore, we interpret the fluorescence signal as reporting on the synthesis of tetra-Cys CRABP I.

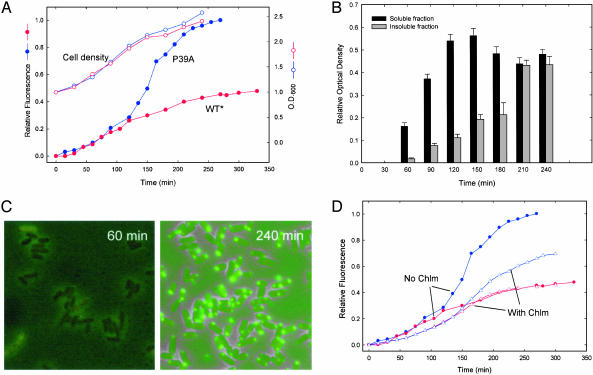

Fig. 3.

(A) Time course of FlAsH fluorescence at 530 nm after lysozyme pretreatment, loading with dye, and IPTG induction of protein expression at time 0 (tetra-Cys CRABP I in red, P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I in blue; filled symbols). Cell density (OD600) is shown in open symbols in the same colors. (B) Time evolution of P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I protein distribution between soluble and insoluble fractions from cell fractionation (note that all of the tetra-Cys CRABP I remains soluble throughout the same time course). (C) Fluorescence microscopy of cells at 60 min (Left) or 240 min (Right) postinduction showing increasing number of highly fluorescent inclusion bodies with polar distribution. (D) Effect of chloramphenicol (Chlm) treatment at a concentration that reduces translation (and therefore concentration of expressed protein) on the time course of FlAsH-labeled P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I fluorescence. Note the longer apparent lag time in the presence of chloramphenicol (⋄) before the striking increase in fluorescence of FlAsH-labeled P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I.

By contrast with these results for the labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I, which remains soluble in the cell, fluorescence from labeled P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I first followed the same curve as the FlAsH-labeled tetra-Cys CRABP I, then increased sharply at about 120 min (Fig. 3A, filled blue circles). Fractionation of cell lysates revealed the initial formation of protein aggregates at ≈60 min, and maximal insoluble material was formed at about 210 min (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, FlAsH fluorescence seemed to increase more rapidly than the fraction of insoluble material (compare Fig. 3 A and B). Because the dye-bound protein is hyperfluorescent in the unfolded state relative to the folded state, the fluorescence reports on partially unfolded states and preaggregates, as well as well formed inclusion bodies. We thus speculate that the earlier times reflect the comparable expression levels of either the soluble tetra-Cys CRABP I or P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I, with largely native protein in each case but a significant and growing concentration of partially folded states for the latter, slow-folding mutant. When the population of partially folded (or other nonnative intermediates) reaches a critical threshold, aggregation and formation of inclusion bodies ensues.

Consistent with this interpretation are the results of fluorescence microscopy. We examined samples of E. coli cells pre-loaded with FlAsH at intervals following IPTG induction of P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I. Early on (Fig. 3C Left), fluorescence was observed to increase throughout the cytoplasm; a few cells displayed small highly fluorescent aggregates located at the poles, reminiscent of the polarization described for many bacterial functions (23). After 90 min, the formation of aggregates was more widespread in the cells expressing the slow-folding mutant, and these aggregates increased in size and were present in nearly all cells after 120 min (Fig. 3C Right). Very little indication of aggregation was observed in cells expressing the tetra-Cys CRABP I without the P39A mutation over the same time course (data not shown).

In vitro studies have shown that protein aggregation is characterized by a lag phase (3). This lag is interpreted to arise from a build up of partially folded, aggregation-prone insoluble states. When the concentration of these species reaches a critical point, aggregation ensues. Hence, lowering the protein concentration should increase the apparent lag time. We treated the cells expressing P39A tetra-Cys CRABP I with chloramphenicol at a low concentration to reduce translation and hence the amount of translated product. As would be predicted if the significant enhancement of fluorescence signifies a concentration threshold for aggregation, the apparent lag time before enhancement of fluorescence and development of inclusion bodies increased as a consequence of the chloramphenicol treatment (Fig. 3D).

Conclusions

Our approach has enabled the direct observation of protein production and aggregation in real time in bacterial cell cultures and therefore opens the door to exploration of how cellular factors, such as molecular chaperones, or environmental variables, such as temperature, affect the rate and amount of aggregation and to the testing of potential therapeutic agents that might modulate aggregation (24, 25). Our results complement previous efforts to follow protein aggregation in vivo (26–30). However, studies that allow direct observation of aggregation without analysis of cell constituents after lysis are rare (31, 32). Wigley et al. (32) used β-galactosidase activity in a colorimetric assay as a way of reporting on the solubility of a fusion protein. Others have devised experiments to follow the appearance of successfully folded product in vivo. For example, Waldo et al. (33) designed an in vivo protein folding assay using N-terminal fusions to GFP to identify proteins that did not aggregate, but did not directly observe aggregation events. Philipps et al. (34) proposed a screening approach to observe folding and stability based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer between flanking C-terminal GFP and N-terminal blue fluorescent protein.

Our work has expanded the structural range of possible sites for insertion of a tetra-Cys binding motif for FlAsH and related dyes in a protein of interest. Previous reports included using these motifs as N- or C-terminal tags, or their incorporation into adjacent helical turns in calmodulin (4, 13, 14). The results with CRABP I suggest that loops may be apt sites for tetra-Cys insertion, particularly in cases where natural variation has been seen in the loop sequence. We emphasize that there are distinct advantages to the incorporation of the tetra-Cys motif in the protein of interest, in contrast with the construction of fusions with fluorescent proteins like GFP. Most obviously, the probe is reporting directly on the protein of interest. Additionally, the time scale accessible to fluorescence measurements in cells is potentially reduced both because the dye binding is fast (14) and because the length of the dye-binding sequence is small and hence rapidly translated. Transport of the dye across the cell membrane can present a significant time lag, but in our case, preloading of the cells with dye avoided this delay.

Carrying out studies of aggregation with a protein such as CRABP I, whose folding is well characterized in vitro, will provide insight into the nature of the species that initiate the aggregation process. Moreover, the process of aggregate formation can be examined in detail in vitro and correlated with in vivo events. This simple system using an E. coli expression system serves as a paradigm for similar analyses of aggregation in eukaryotic cells, including mammalian cells, and should complement active work on aggregation in these systems (7, 35). Thus, it may provide an experimental platform for studies of amyloidogenesis and other pathological protein aggregation events and enable tests of therapeutic approaches to counteract these processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jesse McCool and Steven Sandler for help with the fluorescence microscopy and Annie Marcelino for measuring unfolding rates oftetra-Cys CRABP I. We appreciate critical reading and fruitful discussion of the manuscript by several colleagues and by Gierasch laboratory members, particularly Stephen Eyles, Jennifer Habink, Kenneth Rotondi, and Joanna Swain. This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant GM27616 (to L.M.G.) and Postdoctoral Fellowship 1425/TUHH (to Z.I.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: CRABP I, cellular retinoic acid-binding protein I; EDT, ethanedithiol; FlAsH, fluorescein bisarsenoxide; IPTG, isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside.

Footnotes

Habink, J. A. & Gierasch, L. M. (2002) Biophys. J. 82, 1460a (abstr.).

References

- 1.Betts, S., Haase-Pettingell, C. & King, J. A. (1997) Adv. Prot. Chem. 50, 243–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horwich, A. (2002) J. Clin. Invest. 110, 1221–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fink, A. L. (1998) Folding Des. 3, R9–R23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang, J., Campbell, R. E., Ting, A. Y. & Tsien, R. Y. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 906–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banaszak, L., Winter, N., Xu, Z., Bernlohr, D. A., Cowan, S. & Jones, T. A. (1994) Adv. Protein Chem. 45, 89–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark, P. L., Weston, B. F. & Gierasch, L. M. (1998) Folding Des. 3, 401–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milewski, M. I., Mickle, J. E., Forrest, J. K., Stanton, R. A. & Cutting, G. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34462–34470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, P. L., Liu, Z. P., Rizo, J. & Gierasch, L. M. (1997) Nat. Struct. Biol. 4, 883–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sukumar, M. & Gierasch, L. M. (1997) Folding Des. 2, 211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotondi, K. S. & Gierasch, L. M. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 7976–7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunasekaran, K., Hagler, A. T. & Gierasch, L. M. (2004) Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 54, 179–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Netzer, W. J. & Hartl, F. U. (1997) Nature 388, 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffin, B. A., Adams, S. R., Jones, J. & Tsien, R. Y. (2002) Methods Enzymol. 327, 565–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams, S. R., Campbell, R. E., Gross, L. A., Martin, B. R., Walkup, G. K., Yao, Y., Llopsis, J. & Tsien, R. Y. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 6063–6076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, H. C. & Bernstein, H. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43527–43535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pace, C. N., Shirley, B. A. & Thompson, J. A. (1989) in Protein Structure: A Practical Approach, ed. Creighton, T. E. (IRL, Oxford), pp. 311–330.

- 17.Fersht, A. (1999) Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science (Freeman, New York), pp. 508–539.

- 18.Eyles, S. J. & Gierasch, L. M. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 301, 737–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang, J., Liu, Z. P., Jones, T. A., Gierasch, L. M. & Sambrook, J. F. (1992) Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 13, 87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghaemmaghami, S. & Oas, T. G. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 879–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis, R. J. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers, J. K., Pace, C. N. & Scholtz, J. M. (1995) Protein Sci. 4, 2138–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro, L., McAdams, H. H. & Losick, R. (2002) Science 298, 1942–1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammarstrom, P., Wiseman, R. L., Powers, E. T. & Kelly, J. W. (2003) Science 299, 713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apostol, B. L., Kazantsev, A., Raffioni, S., Illes, K., Pallos, J., Bodai, L., Slepko, N., Bear, J. E., Gertler, F. B., Hersch, S., et al. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 5950–5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haase-Pettingell, C. & King, J. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 4977–4983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King, J., Haase-Pettingell, C., Robinson, A. S., Speed, M. & Mitraki, A. (1996) FASEB J. 10, 57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein, J. & Dhurjati, P. (1995). (1995) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 1220–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrió, M. M. & Villaverde, A. (2003) FEBS Lett. 537, 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas, J. G. & Baneyx, F. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 11141–11147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lansbury, P. T., Jr. (2001) Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 112–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wigley, W. C., Stidham, R. D., Smith, N. M., Hunt, J. F. & Thomas, P. J. (2001) Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waldo, G. S., Standish, B. M., Berendzen, J. & Terwilliger, T. C. (1999) Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Philipps, B., Hennecke, J. & Glockshuber, R. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 327, 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajan, R. S., Illing, M. E., Bence, R. F. & Kopito, R. R. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13060–13065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]