Abstract

H2O will be more resistant to metallization than previously thought. From computational evolutionary structure searches, we find a sequence of new stable and meta-stable structures for the ground state of ice in the 1–5 TPa (10 to 50 Mbar) regime, in the static approximation. The previously proposed Pbcm structure is superseded by a Pmc21 phase at p = 930 GPa, followed by a predicted transition to a P21 crystal structure at p = 1.3 TPa. This phase, featuring higher coordination at O and H, is stable over a wide pressure range, reaching 4.8 TPa. We analyze carefully the geometrical changes in the calculated structures, especially the buckling at the H in O-H-O motifs. All structures are insulating—chemistry burns a deep and (with pressure increase) lasting hole in the density of states near the highest occupied electronic levels of what might be component metallic lattices. Metallization of ice in our calculations occurs only near 4.8 TPa, where the metallic C2/m phase becomes most stable. In this regime, zero-point energies much larger than typical enthalpy differences suggest possible melting of the H sublattice, or even the entire crystal.

Keywords: hydrogen bonds, compressed water

The phase diagram of H2O exhibits a substantial array of stable and meta-stable crystalline phases, along with two amorphous ices (1). Terrestrial experiment continues to find new phases (2). There are also good cosmochemical reasons to think about the high pressure phases of H2O—ice is a major component of the outer planets in our solar system, presumably forming very dense layers around the rocky cores of Neptune and Uranus (3, 4). And it is likely that ice will be a constituent of similarly sized or larger exoplanets that are currently being discovered (5, 6).

Known and Postulated Ice Structures

As ice is compressed at low temperatures from its hexagonal phase Ih at P = 1 atm, it undergoes a series of phase transitions between different molecular structures. At about 120 GPa, ice is expected to reach a hydrogen-ordered phase, ice X (7–10), in which individual molecules of H2O are no longer discernible. Instead, the hydrogen atoms are located midway between nearest neighbor oxygen atoms, which in turn occupy body centered cubic lattice sites. The O-H distances in ice X are longer than intramolecular O-H distances in an isolated water molecule, or in ice Ih.

At even higher pressures, ice X is found from molecular dynamics simulations to give way to a Pbcm structure (11) between 300 and 400 GPa. Recently, calculations on symmetric structures where hydrogen occupies midpoints between nearest and next nearest neighbor oxygen atoms found phase transitions from Pbcm to a Pbca and a Cmcm structure at 760 and 1,550 GPa, respectively (12). The latter was also calculated to be metallic. Here, we present several new phases of ice calculated to be stable at pressures above 1 TPa. We find the most stable phases to be insulating, hence pushing the transition pressure for metallization of ice beyond 4.8 TPa (corresponding to ∼12-fold compression).

Searching Methodology

Finding thermodynamically stable structures for solids of given stoichiometry is a notoriously difficult task (13), which remains true even for transitions between ground state structures, as considered in what follows. When chemical intuition (14) fails one possible method to effectively and efficiently sample the configurational space of solid state structures for a given stoichiometry utilizes genetic or evolutionary algorithms. Such algorithms have been used originally for isolated molecules and clusters, (15–17), but also for extended systems (18, 19). Genetic or evolutionary algorithms rely on concepts borrowed from biological evolution to locate the global minimum on the potential energy surface. Here, we use the open source program XtalOpt (20) to perform an evolutionary algorithm based structure search. For a proposed structure the enthalpies are computed by density functional theory (DFT) with the VASP software package (21), making use of the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof parametrization of the exchange-correlation energy density (22), and the Projector Augmented Wave (PAW) method to describe the electron-ion interaction (23, 24). We use “hard” PAW datasets, with outermost cutoff radii for hydrogen and oxygen of 0.8 and 1.1 Bohr radii, respectively. A plane wave energy cutoff of 800 eV was employed, and Brillouin zones were sampled with a linear k-point density of 20 Å.

We performed structure searches at p = 1 TPa and p = 2 TPa with Z = 4 molecules per unit cell, and used the above mentioned ice X, Pbcm, and Cmcm structures, as well as random structures, as starting points for the workings of the evolutionary algorithm. As a check, a structure search at p = 2.5 TPa with Z = 8 molecules (unit cell doubled), and a structure search at p = 5.0 TPa with Z = 4 molecules, both seeded with all previously found low-enthalpy structures, did not result in new structures.

New Ices at Higher Pressures: Enthalpies

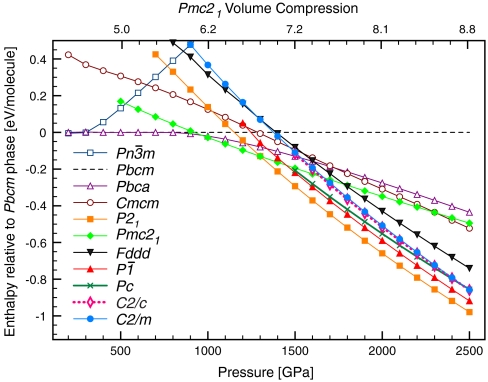

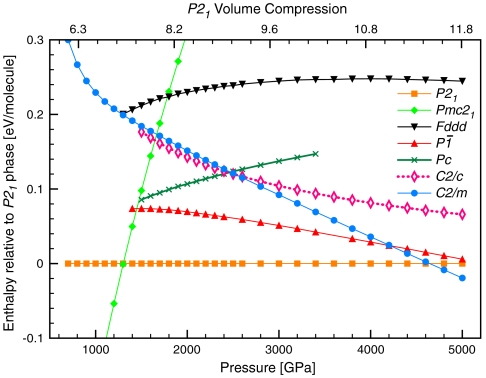

We find several new crystal structures of ice; these substantially change the phase diagram that theory has hitherto provided for the ground states at pressures above p = 1 TPa. Fig. 1 gives the computed enthalpies per H2O at various pressures up to 2.5 TPa. A Pmc21 structure with four molecules per unit cell is enthalpically favored over the previously proposed Pbca structure above p = 930 GPa, and is succeeded above p = 1,300 GPa by a P21 structure, also with four molecules per unit cell. Remarkably, the relative stability of P21 ice increases rapidly over that of all previously known structures.

Fig. 1.

Relative ground state enthalpies of known and new ice crystal phases. Zero-point motion is not included. Upper horizontal axis shows the volume compression of Pmc21 phase relative to ice XI (the H-ordered ground-state phase of ice) at P = 1 atm (25).

In addition to these most stable structures, we found a variety of other structures at p = 2 TPa, all more stable than any previously proposed structure. The enthalpies of the most competitive new structures are also shown in Fig. 1. Structural details of the new phases are listed in SI Appendix, Table SM1; the corresponding equation of state V(p) is given in SI Appendix, Fig. S1.

Structural Hallmarks of the Ice Structures Around 1 TPa

We begin with the Pmc21 structure, which is in our calculations the most stable phase (not by much, and more on this later) in the range p = 1 to 1.3 TPa. The Pmc21 structure, shown in the right column of Fig. 2, in contrast to the Pbcm structure, ice X, and other ice phases at lower pressures, does not feature two interpenetrating fourfold coordinated hydrogen bonded networks. Instead, the entire crystal is connected by pairwise O-H-O bridging bonds.

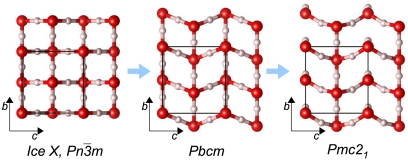

Fig. 2.

From left to right: crystal structures of ice X ( ), Pbcm, and Pmc21, seen along the a axis. Unit cells are indicated (

), Pbcm, and Pmc21, seen along the a axis. Unit cells are indicated ( cell for ice X). All structures are at p = 700 GPa (and ground-states).

cell for ice X). All structures are at p = 700 GPa (and ground-states).

Putting the Pmc21 structure in a sequence with the ice X and Pbcm structures, a picture emerges (see Fig. 2) that illuminates the transition with increasing pressure from three-dimensional interpenetrating networks to two-dimensional corrugated sheets (12). In the transition from ice X to Pbcm the topology of O-H-O bridging bonds remains the same but adjacent layers in the ab plane are sheared with respect to each other, while all bridging bonds remain linear. In the transition from Pbcm to Pmc21, O-H-O bonds in half of these layers rearrange to form O-H-O bonds in a different direction (roughly they change from along the b axis to along the a axis), hence connecting previously independent networks. These bonds are buckled (the O-H-O angle is θ = 146° at p = 1.2 TPa), and the O atoms that are involved in the buckled bonds deviate significantly from ideal tetrahedral coordination.

Fig. 2, SI Appendix, Fig. S2 illustrate this structural sequence and the role of the Pmc21 structure as a successor of the  and Pbcm structures—and also as a precursor to the Cmcm structure, into which it would transform at about p = 2.3 TPa, were it not for a slew of other, more stable structures, which are discussed below. We find that a direct interpolation transition path between the Pbcm and the Pmc21 structure at p = 700 GPa has to overcome a transition barrier of only 0.11 eV per molecule (which may be compared with a zero-point energy of 1.00 eV per molecule, see below).

and Pbcm structures—and also as a precursor to the Cmcm structure, into which it would transform at about p = 2.3 TPa, were it not for a slew of other, more stable structures, which are discussed below. We find that a direct interpolation transition path between the Pbcm and the Pmc21 structure at p = 700 GPa has to overcome a transition barrier of only 0.11 eV per molecule (which may be compared with a zero-point energy of 1.00 eV per molecule, see below).

Structures Above 1 TPa

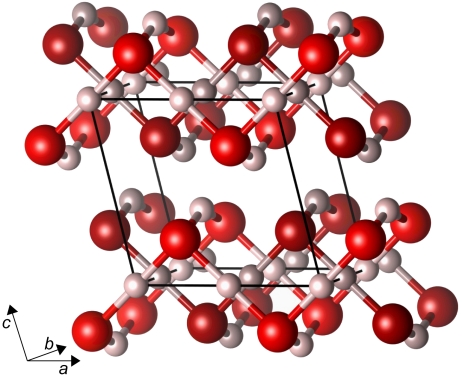

At p = 1.3 TPa the P21 structure becomes the most stable structure, and remains such up to 4.8 TPa. The P21 structure, see Fig. 3, is a three-dimensional O-H-O bonded network. It is the first stable ice structure where O atoms are clearly more than fourfold coordinated to H atoms; that in turn implies that H atoms are more than twofold coordinated to neighboring O atoms.

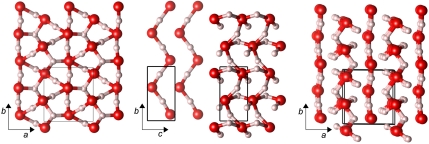

Fig. 3.

Various views of the P21 structure. Left: along c axis; middle: two sublattices (see text), along a axis; right: superposition of sublattices, view close to c axis.

If a coordination number is defined via a “largest gap” definition in the neighbor distance histograms, then all O atoms in the P21 structure are fivefold coordinated to H atoms, and thus half of the H atoms in the crystal are threefold coordinated to neighboring O atoms (see SI Appendix, Fig. S3 for the histogram plots). The O-H connections drawn in Fig. 3 correspond to this definition of coordination.

The P21 structure recites structural elements seen in lower pressure structures: half of its O atoms form linear chains along the b axis (kinked along c), see the middle box of Fig. 3. These chains have almost linear O-H-O bonds (θ = 171° at p = 2 TPa), and are the basic building block of e.g., the Cmcm structure, cf. SI Appendix, Fig. S2. The remaining O atoms form a highly distorted bonded network, see middle box of Fig. 3 (but even there an imaginative eye might discover kinked chains along the b axis, connected through buckled and twisted O-H-O bonds).

In the right box of Fig. 3, we show both “sublattices” together: the quasi-linear and the severely twisted chains alternate along the a axis. These two sublattices are of course connected, and separating them as we do is to some extent arbitrary. However, this specific decomposition of the structure shows what drives its stabilization: it seems that kinked linear O-H-O-connected chains are a desired feature for ice under pressure, as they occur in the Pbcm, the Pmc21, and also the Cmcm structures. Beyond p = 1.3 TPa, however, it is preferred if some of these chains “give in” and form buckled, hence more compact, networks. The persistence of the linear chain motif in a sublattice of the P21 structure is a remnant of its lower pressure alternatives. We will return later to the reasons the high pressure ice phases favor buckled O-H-O units.

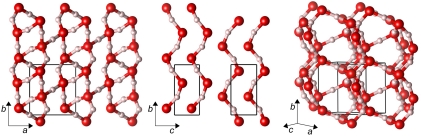

Closely related to the P21 structure is a  structure we find to be the second most stable crystal structure over a wide pressure range, see Fig. 1. The structure of the

structure we find to be the second most stable crystal structure over a wide pressure range, see Fig. 1. The structure of the  phase is shown in Fig. 4. Very similar to P21, the

phase is shown in Fig. 4. Very similar to P21, the  phase is also a three-dimensional O-H-O bonded network which, depending on the definition of the O coordination number, consists of two interpenetrating sublattices (as shown in Fig. 4) or a fully connected network. Again we can identify two sublattices of slightly kinked chains running along the b axis, see middle box of Fig. 4. Here, in contrast to the P21 structure where one chain is quasi-linear and the other one highly distorted, both chains are moderately buckled. Each O atom is connected to two neighboring chains, in a way that forms two separate networks. One of these is shown in the right box of Fig. 4: instead of buckled chains with O-H-O connections, it can also be seen as sheets of edge-sharing (OH)6 rings connected by O-H-O motifs. Either way, the

phase is also a three-dimensional O-H-O bonded network which, depending on the definition of the O coordination number, consists of two interpenetrating sublattices (as shown in Fig. 4) or a fully connected network. Again we can identify two sublattices of slightly kinked chains running along the b axis, see middle box of Fig. 4. Here, in contrast to the P21 structure where one chain is quasi-linear and the other one highly distorted, both chains are moderately buckled. Each O atom is connected to two neighboring chains, in a way that forms two separate networks. One of these is shown in the right box of Fig. 4: instead of buckled chains with O-H-O connections, it can also be seen as sheets of edge-sharing (OH)6 rings connected by O-H-O motifs. Either way, the  structure shows us a different structural path away from linearly O-H-O connected chains. Ultimately, we find that at p = 4.2 TPa (static calculation) the

structure shows us a different structural path away from linearly O-H-O connected chains. Ultimately, we find that at p = 4.2 TPa (static calculation) the  structure becomes unstable with respect to the C2/m structure.

structure becomes unstable with respect to the C2/m structure.

Fig. 4.

Various static lattice views of the  structure. Left: along the c axis; middle: the two sublattices, along the a axis; right: one of the two interpenetrating networks.

structure. Left: along the c axis; middle: the two sublattices, along the a axis; right: one of the two interpenetrating networks.

Several other new structures, of Pc, C2/c, and Fddd symmetry, were found to be within 0.2 eV/molecule of the most stable P21 structure. The structural details of these phases are given in the SI Appendix.

Phase Transitions Near 5 TPa

Boldly extending the enthalpy curves of the most favored P21 and C2/m structures to even higher pressures, we find a transition from the P21 to the C2/m phase at p = 4.8 TPa. The evolution in enthalpy of various phases to high pressures is shown in Fig. 5 (note the relative enthalpies in Fig. 5 are now referred to those of the P21 phase).

Fig. 5.

Ground state enthalpies of new ice structures up to p = 5 TPa, relative to the P21 structure. Upper x axis gives the volume compression of P21 structure relative to ice XI at 1 atm.

The C2/m structure is closely related to the Cmcm phase, see Fig. 6; whereas the latter comprises stacked corrugated sheets internally connected through O-H-O bridging bonds buckled inwards, the former features pairwise interpenetrating corrugated sheets of the same topology, but internally connected through O-H-O bridging bonds these being buckled outwards. One consequence is that the C2/m structure contains linear chains of H atoms spaced by b/2 along the b axis, with H-H distances ranging from 1.01 Å at p = 1 TPa to 0.92 Å at p = 2.5 TPa and 0.88 Å at p = 4 TPa.

Fig. 6.

Static crystal structure of C2/m phase, at p = 2 TPa. Different levels of brightness of atoms indicate separate sublattices.

Such short H-H separations happen to be in the range of H-H separations in elemental hydrogen under pressure, at least as the latter is approximated in calculation. In the recent McMahon and Ceperley work on hydrogen in roughly the same pressure range that we cover, H-H separations between 0.87 Å (p = 1.5 TPa) and 0.83 Å (p = 5.0 TPa) are obtained for various structures of atomic hydrogen (26).

Another view of the C2/m structure is that it is inherently two-dimensional, featuring bilayers of interpenetrating sheets in the ab plane which are not connected along the c axis. However, as we will see, structural low-dimensionality is not reflected on the electronic level—and this holds true also for the Cmcm structure. We do find that both the C2/m and Cmcm structures, at very high pressures (from about p = 4 TPa onwards), exhibit an interesting fivefold O atom coordination, similar to the P21 structure discussed above: this happens as adjacent corrugated sheets are pressed closer to each other along the c axis (b axis for Cmcm), and intersheet O-H distances decrease to approach intrasheet O-H distances.

Dynamical Properties

To examine possible changes arising from departures from the static lattice approximation we studied the dynamical stability of these new structures using the PHON program (27), calculating the emerging force constant matrices within the harmonic approximation (see SI Appendix for more detailed information). The enthalpically stable phases are also dynamically stable in their respective pressure ranges: Pmc21 for p = 1…1.3 TPa, and P21 for p≥1.3 TPa. Other structures are meta-stable. The zero-point vibrational energies (ZPE) for all phases are large, ranging (for the P21 structure) from 1.06 eV/molecule at p = 1 TPa via 1.37 eV/molecule at p = 2.5 TPa to 1.70 eV/molecule at p = 5 TPa. As might be expected, most of this zero-point energy resides in motion of the hydrogens (e.g., 1.06 eV/molecule at p = 2.5 TPa). However, differences in ZPEs among the various phases are below 50 meV/molecule, and thus are smaller than characteristic total energy differences between the phases for pressures p ≤ 2.5 TPa. The inclusion of the ZPEs, however, shifts the transition pressure for the Pbcm → Pmc21 transition to 880 GPa, and for the Pmc21 → P21 transition to 1,170 GPa.

For pressures larger than p = 2.5 TPa, several phases come very close to each other in enthalpy, and inclusion of their ZPEs actually changes their enthalpic order. The  structure becomes the most stable phase at p = 3.6 TPa, and its transition into the C2/m phase does not happen until about p = 6 TPa. SI Appendix, Fig. S4 shows the evolution of the enthalpy curves of these phases with zero-point effects included. Even though the latter differ by only 2.5% (comparing e.g., the

structure becomes the most stable phase at p = 3.6 TPa, and its transition into the C2/m phase does not happen until about p = 6 TPa. SI Appendix, Fig. S4 shows the evolution of the enthalpy curves of these phases with zero-point effects included. Even though the latter differ by only 2.5% (comparing e.g., the  and P21 phases at p = 3.6 TPa), this is sufficient to overcome the total energy difference between these phases, and substantially shift the transition pressures and thus also the onset of stability of metallic ice.

and P21 phases at p = 3.6 TPa), this is sufficient to overcome the total energy difference between these phases, and substantially shift the transition pressures and thus also the onset of stability of metallic ice.

The phonon dispersion relations and density of states for the P21 structure at p = 2 TPa are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5. Vibrations of the H sublattice reach frequencies of 150 THz, or 5,000 cm-1 (or over 500 meV). Such frequencies are quite high, but they are reasonable, as a molecular model we study below will show.

Metallic Ice?

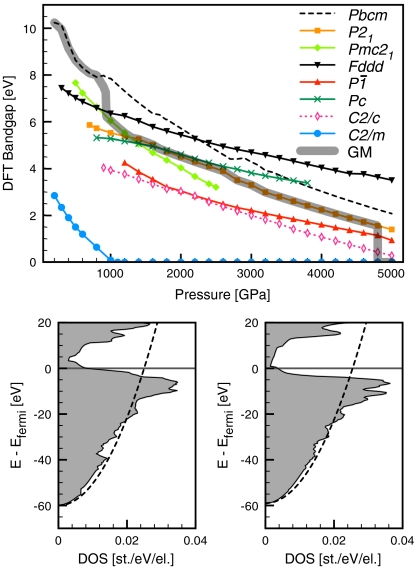

Previous static calculations have suggested a transition to a metallic ice phase at pressure less than p = 2 TPa. We find more stable phases in this pressure regime, and they are far from metallic even though the bands are quite wide (about 50–55 eV). The Pmc21, P21, and  structures are calculated to be insulating, with substantial band gaps of more than 3 eV even at p = 2.5 TPa, see Fig. 7. The trend of large band gaps in molecular and atomic ice phases, which even increase initially under pressure (25), is continued. The only metallic structure we find, C2/m, whose DFT band gap in our calculations closes at p = 1.1 TPa, is just not competitive in this pressure regime, see Fig. 1.

structures are calculated to be insulating, with substantial band gaps of more than 3 eV even at p = 2.5 TPa, see Fig. 7. The trend of large band gaps in molecular and atomic ice phases, which even increase initially under pressure (25), is continued. The only metallic structure we find, C2/m, whose DFT band gap in our calculations closes at p = 1.1 TPa, is just not competitive in this pressure regime, see Fig. 1.

Fig. 7.

Top: DFT band gaps for various static ice structures, up to p = 5 TPa; the gray band indicates the global minimum (GM) band gap curve. Bottom: electronic DOS (in states per electron per eV) for metallic C2/m phase and its O2- sublattice, at p = 4.8 TPa. The dashed line in the DOS plots indicates a free-electron DOS per electron with a bandwidth of 60 eV (left) and 59 eV (right).

Fig. 7 (top box) illustrates both the traditional notion that insulating phases, where such may exist, are favored over coexisting metallic phases. And that there is no correlation between stability and size of the band gap for these insulating phases.

However, at the top of the pressure range we study statically, at p = 4.8 TPa, a metallic phase, C2/m, does become more stable than its insulating competitors (dynamical effects shift this onset of metallization to even higher pressures). The electronic density of states (DOS) for this phase is also shown in Fig. 7 (bottom box), its band structure is plotted in SI Appendix, Fig. S6. The valence bandwidth at almost 5 TPa pressure is about 60 eV; the DOS is very much free-electron like at low energies, with minor features that correspond to the pseudopotential. At the Fermi level, however, the DOS is depleted significantly (for free electrons it would be 3/2Ef or 0.025 states per electron per eV), making the C2/m phase a rather ordinary metal even at these high pressures. There is no sign, however, of low-dimensional electronic character, and neither can it be found in the Cmcm structure (see SI Appendix, Fig. S7 for its electronic DOS).

Chemistry

While P21 is insulating, at its stability onset of p = 1.3 TPa both its O and H sublattices would separately be metallic. There are two ways to think about the insulating character of ice: One is to say that OH bond formation, partially covalent, burns a deep gap in the DOS at the Fermi level. Alternatively, coexistence of O and H in the lattice allows the electron transfer that electronegativity mandates, this towards a formal (H+)2(O2-) extreme. And the configuration of these ions is a closed shell one. Either way, chemistry makes a tremendous difference.

Even when metallicity appears around 5 TPa, the ionic perspective retains its value. Consider the band structure and DOS of the O2- sublattice of the C2/m structure at 4.8 TPa—a calculation on a lattice of O2- ions at the same positions as the oxygens in C2/m, with the H atoms removed and replaced by a constant background charge compensating the excess electronic charge of the unit cell—as shown in the bottom box of Fig. 7 and in SI Appendix, Fig. S6. The two electronic structures—H2O and the O2- sublattice—are very similar. Highly compressed ice therefore behaves like a network of highly compressed oxide ions—the presence of the protons is necessary to avoid a Coulomb explosion, but nevertheless changes the electronic properties very little. The same is true for the insulating P21 phase (see SI Appendix, Fig. S8). O2- is isoelectronic to neon; perhaps this makes it less surprising to see ice remain insulating to very high pressure.

Is Water More or Less Polar When Pressurized?

Water in its extended phases has an increased dipole moment compared to the single molecule (28, 29) (although it may be prudent to have some reservations about identifying electrostatic moments in the close quarters of a molecular crystal, especially under high pressures). In the structures beyond ice X we study, there are no identifiable water molecules. But we can still think about the ionicity of the O and H components. There is an inherent difficulty in assigning electronic density to individual atoms when using plane wave basis sets. Here, we choose to project the valence charge density onto atomic spheres around each atom that just touch; i.e., the O and H sphere radii rO and rH are adjusted to add up to the shortest O-H distance at each pressure, with rO = 2 × rH (roughly the cube roots of the atom/ion valence electron counts). Then, we scale these localized electron counts such that they add up to the number of electrons in the unit cell. If we compare the electron densities/charges thus obtained (see SI Appendix, Fig. S9), we find a slight decrease in ionicity under pressure, and for all competitive high pressure phases. To be specific, the valence electron density on O (which should be six electrons for a neutral atom) reduces from 7.22 at 2 TPa to 7.12 at 4.8 Tpa.

We also tried to assign charges to atoms through a topological analysis of the electronic density (30, 31). We obtain similar electron densities to those found with the method described above—with a still less pronounced trend under increased pressure, and with highly distorted atom-centered domains around the O atoms.

We might mention at this point a general concern about electron density in highly compressed matter, and this pertains to valence electron density as we move away from the nuclei. Such deformations were first found for elemental lithium (32) and have since been observed for other elemental structures. We looked carefully for this phenomenon in ice, and found even at the highest pressures no density maximum in the interstitial space between the atoms.

Why do Hydrogens go “Nonlinear” at High Pressures?

The progression we see in H2O structures as the pressure rises has some expected features, and also some unusual ones. The expected feature is a rise in coordination at O and at H, starting from the molecular two-coordination at the oxygen and singly coordinated hydrogens. In the ice X structure we find four-coordination (in H) at O, and two-coordination at H. And, as we have seen, higher pressure brings us to still higher coordination at O and at H.

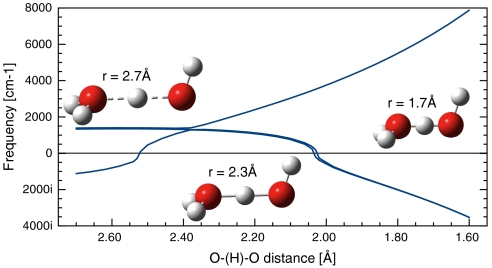

An interesting geometrical feature we find in the structures evolving after ice X is that the O-H-O linkage goes progressively nonlinear at H. Why does this nonlinearity happen? We investigated this effect with a molecular model, shown in Fig. 8. Two water molecules were brought together in a classical hydrogen bonding arrangement except that the O-H-O central unit was kept symmetrical (both OH separations maintained as equal) and linear. The OO separation (a surrogate for pressure) was then varied, and the normal modes of vibration for the central H atom then calculated [here using the Gaussian program suite, the B3LYP exchange-correlation functional, and augmented triple zeta basis sets (33–36)].

Fig. 8.

Vibrational frequencies for H atom in the center-position of the O-H-O bridging bond (see text).

In Fig. 8, the normal mode (vibron) at around 1,400 cm-1 is the OHO-bending vibration, and the rising higher frequency mode is the asymmetric stretch. If we let the central hydrogen depart from left-right equality, or OHO colinearity, it indeed would do so outside the region 2.52 Å≥r(OO)≥2.03 Å. At longer O-O separations the hydrogen would remain linear (or at least close to linear), but move closer to one oxygen, at shorter O-O it would go out-of-the-line, or buckle. In the calculated ice phases, the stability onset of symmetrically bonded ice X is at p = 120 GPa, with rOO = 2.27 Å; and the first buckled O-H-O bonds in ice occur at p = 800 GPa in the Pbca structure, where rOO = 1.97 Å. Observe how nicely the appearance of imaginary frequencies in the simple molecular model now agrees with these onsets of departure from symmetric linear geometry for O-H-O. An even simpler ansatz, suggested to us by a reviewer, where both the O-H and the O-O interaction are described by Morse potentials (37), leads qualitatively to the same result (see the SI Appendix for more details).

But the question still remains: why do the hydrogens go off-line? We think the answer is that under pressure one needs to increase further the O coordination in other oxygens and not only hydrogens. And that is most simply accomplished by bending at the hydrogens.

High Zero-Point Energies and a Possible Liquid Phase

As we see in the molecular model discussed above, the vibration of H along the O-H-O axis indeed reaches the substantial value of 5,000 cm-1 and more (exceeding 0.6 eV), if the oxygen atoms are brought to within rOO = 1.80 Å or less. This energy is at the top of the frequency spectrum for the P21 phase at p = 2 TPa, see SI Appendix, Fig. S5. Accordingly might the high zero-point vibrational energies associated with this H motion then perhaps result in a melting of the H sublattice, or even the whole ice crystal structure at sufficiently high pressures? The phenomenon of reentrant melting under pressure has been found recently, for example, in the alkali metals Li and Na (38–40), and the dissociation of hot dense water and different mobilities for its constituents H and O have been reported both from molecular dynamics simulations and experiment (41–43).

In support of the notion of cold superionic high pressure ice it may be mentioned that a typical barrier to concerted diffusion of H atoms between lattice sites in the P21 structure at p = 2 TPa is just 0.7 eV, (to be compared with 0.5 eV as the hydrogen and harmonic approximation based zero-point energy). There are certainly a variety of crystalline phases with very similar enthalpies of formation at p≥4 TPa, and the zero-point energies are also much larger than their enthalpy differences. It is not hard to imagine that at least the protons would use the zero-point motion to adopt a fluctuating mixture of crystalline phases; i.e., a liquid and in this context the replacement of hydrogen by deuterium could be quite revealing. Either for water or for heavy water the issue of metallization possibly setting in earlier, in association with the diffusive or sublattice melted state, then becomes quite pertinent.

Conclusions

To summarize, we have found a number of new ground state phases of ice under extremely high pressures but perhaps typical of some planetary conditions. A revised phase diagram for ice in the TPa pressure regime is suggested, with a phase transition into a Pmc21 structure at p = 0.93 TPa followed by a transition into a P21 structure at p = 1.3 TPa. Both of these phases are large gap insulators. Clearly, the interaction of O and H makes a difference—chemistry “burns” a large and persistent (with pressure) hole in the upper reaches of the density of states of two metallic sublattices, O and H. Or, alternatively, the capacity for electron transfer from H to O, makes compressed H2O very different from its neutral sublattices.

In the new high pressure ices that we propose, we see a tendency to buckle or bend at the H in O-H-O motifs, a phenomenon we trace to the increased coordination made available by this motion. Metallization of ice is not found until p = 4.8 TPa in static calculations (and even higher when dynamical effects are estimated at the level of the harmonic approximation), when a C2/m structure, this related to a recently suggested Cmcm structure, becomes the most stable phase. These findings, especially the “delayed” metallization of ice, should have significance beyond the ground states considered here and hence for modeling the interiors of some massive gas planets. There is another possibility that also merits further examination, namely that because of the possible onset of H (or D) diffusion, high pressure ices may adopt fluid states. After our work was completed, we became aware of several new studies of high pressure ice phases (44–46). The structures obtained in these studies mostly agree with ours.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Andreas Hermann wishes to acknowledge Peter Schwerdtfeger for piquing his interest in high pressure studies of water and ice. We thank two reviewers for their comments. Our work was supported by EFree, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the Department of Energy (Award Number DESC0001057 at Cornell) and the National Science Foundation through Grants CHE-0910623 and DMR-0907425. Computational resources provided by the Cornell NanoScale Facility (supported by the National Science Foundation through Grant ECS-0335765), and by the TeraGrid network (provided by the National Center for Supercomputer Applications through Grant TG-DMR060055N), are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1118694109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Petrenko VF, Whitworth RW. Physics of Ice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salzmann CG, Radaelli PG, Mayer E, Finney JL. Ice XV: A New Thermodynamically Stable Phase of Ice. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;103:105701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.105701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross M. The ice layer in Uranus and Neptune—diamonds in the sky? Nature. 1981;292:435–436. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Podolak M, Weizman A, Marley M. Comparative models of Uranus and Neptune. Planet Space Sci. 1995;43:1517–1522. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaulieu J-P, et al. Discovery of a cool planet of 5.5 Earth masses through gravitational microlensing. Nature. 2006;439:437–440. doi: 10.1038/nature04441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould A, et al. Microlens OGLE-2005-BLG-169 implies that cool neptune-like planets are common. Astrophys J. 2006;644:L37–L40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benoit M, Marx D, Parrinello M. Tunnelling and zero-point motion in high-pressure ice. Nature. 1998;392:258–261. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loubeyre P, LeToullec R, Wolanin E, Hanfland M, Hausermann D. Modulated phases and proton centring in ice observed by X-ray diffraction up to 170 GPa. Nature. 1999;397:503–506. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benoit M, Romero AH, Marx D. Reassigning hydrogen-bond centering in dense ice. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:145501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.145501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caracas R. Dynamical instabilities of ice X. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;101:85502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.085502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benoit M, Bernasconi M, Focher P, Parrinello M. New high-pressure phase of ice. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;76:2934–2936. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Militzer B, Wilson HF. New phases of water ice predicted at megabar pressures. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105:195701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.195701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maddox J. Crystals from first principles. Nature. 1988;335:201, 201. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grochala W, Hoffmann R, Feng J, Ashcroft N. The chemical imagination at work in very tight places. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:3620–3642. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartke B. Global geometry optimization of clusters using genetic algorithms. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:9973–9976. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston RL. Evolving better nanoparticles: genetic algorithms for optimising cluster geometries. Dalton T. 2003:4193–4207. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Assadollahzadeh B, Bunker PR, Schwerdtfeger P. The low lying isomers of the copper nonamer cluster, Cu9. Chem Phys Lett. 2008;451:262–269. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oganov AR, Lyakhov AO, Valle M. How evolutionary crystal structure prediction works-and why. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:227–237. doi: 10.1021/ar1001318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zurek E, Hoffmann R, Ashcroft NW, Oganov AR, Lyakhov AO. A little bit of lithium does a lot for hydrogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17640–17643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908262106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lonie DC, Zurek E. XtalOpt: An open-source evolutionary algorithm for crystal structure prediction. Comput Phys Commun. 2011;182:372–387. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficient iterative schemes for {it ab initio} total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys Rev B. 1996;54:11169–11186. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.54.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient expansion made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blöchl PE. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys Rev B. 1994;50:17953–17979. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.50.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kresse G, Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys Rev B. 1999;59:1758–1775. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermann A, Schwerdtfeger P. Blueshifting the onset of optical UV absorption for water under pressure. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;106:1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.187403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMahon J, Ceperley D. Ground-state structures of atomic metallic hydrogen. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;106:165302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.165302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alfè D. PHON: A program to calculate phonons using the small displacement method. Comput Phys Commun. 2009;180:2622–2633. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silvestrelli PL, Parrinello M. Water molecule dipole in the gas and in the liquid phase. Phys Rev Lett. 1999;82:3308. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batista ER, Xantheas SS, Jónsson H. Molecular multipole moments of water molecules in ice Ih. J Chem Phys. 1998;109:4546–4551. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bader RFW. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang W, Sanville E, Henkelman G. A grid-based Bader analysis algorithm without lattice bias. J Phys-Cond Mat. 2009;21:084204. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/8/084204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neaton JB, Ashcroft NW. Pairing in dense lithium. Nature. 1999;400:141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frisch MJ, et al. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2004. Gaussian 09 Revision A.02. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becke AD. A new mixing of Hartree-Fock and local density-functional theories. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:1372–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stephens PJ, Devlin FJ, Chabalowski CF, Frisch MJ. Ab Initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:11623–11627. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kendall RA, Dunning TH, Jr, Harrison RJ. Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions. J Chem Phys. 1992;96:6796–6806. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holzapfel WB. On the symmetry of the hydrogen bonds in ice VII. J Chem Phys. 1972;56:712–715. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gregoryanz E, Degtyareva O, Somayazulu M, Hemley R, Mao H-kwang. Melting of dense sodium. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94:1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.185502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guillaume CL, et al. Cold melting and solid structures of dense lithium. Nat Phys. 2011;7:211–214. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rousseau B, Xie Y, Ma Y, Bergara A. Exotic high pressure behavior of light alkali metals, lithium and sodium. Eur Phys J B. 2011;81:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwegler E, Galli G, Gygi F, Hood R. Dissociation of water under pressure. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;87:265501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.265501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldman N, Fried L, Kuo I-F, Mundy C. Bonding in the superionic phase of water. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94:217801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.217801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goncharov AF, et al. Dynamic ionization of water under extreme conditions. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94:125508. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.125508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, et al. High pressure partially ionic phase of water ice. Nat Commun. 2011;2:563–567. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McMahon J. Ground-state structures of ice at high pressures from ab initio random structure searching. Phys Rev B. 2011;84:220104. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ji M, et al. Ultrahigh-pressure phases of H2O ice predicted using an adaptive genetic algorithm. Phys Rev B. 2011;84:220105. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.