Abstract

Overexpression of human cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) in the mammary glands of transgenic mice induces tissue-specific tumorigenic transformation. However, the molecular mechanisms involved are not yet defined. Here we show that COX-2 expressed in the epithelial cell compartment regulates angiogenesis in the stromal tissues of the mammary gland. Microvessel density increased before visible tumor growth and exponentially during tumor progression. Inhibition of prostanoid synthesis with indomethacin strongly decreased microvessel density and inhibited tumor progression. Up-regulation of angiogenic regulatory genes in COX-2 transgenic mammary tissue was also potently inhibited by indomethacin treatment, suggesting that prostanoids released from COX-2-expressing mammary epithelial cells induce angiogenesis. G protein-coupled receptors for the major product, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) EP1-4, are expressed during mammary gland development, and EP1,2,4 receptors were up-regulated in tumor tissue. PGE2 stimulated the expression angiogenic regulatory genes in mammary tumor cells isolated from COX-2 transgenic mice. Such cells are tumorigenic in nude mice; however, treatment with Celecoxib, a COX-2-specific inhibitor, reduced tumor growth and microvessel density. These results define COX-2-derived PGE2 as a potent inducer of angiogenic switch during mammary cancer progression.

Keywords: tumor angiogenesis, prostaglandin E2 receptors, mammary cancer

Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the formation of prostanoids from arachidonic acid and other polyunsaturated fatty acids (1). COX-2 is induced in response to a wide range of cellular perturbations in normal (NM) tissues (1, 2). However, COX-2 expression is up-regulated and appears to be critically involved in human tumorigenesis. Multiple epidemiological studies have indicated that the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which inhibit COX activity, result in decreased risk of cancer development (3, 4). Second, expression of COX-2 and the production of its major product, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), are elevated in various human cancers (4, 5). Third, studies in carcinogen and genetically induced tumor models have shown that NSAIDs, and COX-2 selective inhibitors in particular, have profound suppressive effects on tumor development (6, 7). Finally, deletion of the COX-2 gene suppressed tumor progression in mice predisposed to intestinal neoplasia (8). These data provide compelling evidence that COX-2 is an obligatory player in human cancer.

COX-2 is overexpressed in breast cancer tissues, and the extent of expression is associated with poor prognosis (9). Various environmental and nutritional risk factors for breast cancer induce COX-2 expression in animal models (10, 11). In addition, COX-2-selective inhibitors significantly delayed the incidence of mammary tumors in transgenic mice expressing the Her2/Neu oncogene (12). Moreover, PGE2 is elevated in mammary tumors and is known to induce the enzyme aromatase, which is critical for the local synthesis of estrogen (13). Recently, we developed a transgenic mouse model in which the human COX-2 gene is expressed in the mammary gland under the control of the murine mammary tumor virus promoter and demonstrated that enhanced COX-2 expression strongly predisposes the transformation of the mammary gland in multiparous animals (14). These data strongly suggest that local expression of COX-2 is sufficient for in situ tumor initiation and/or progression. Another transgenic overexpression study with COX-2 targeted to the epidermis also supports the concept that it is a critical regulator of tumor progression (15). However, the molecular mechanisms involved are not well understood, particularly in relevant animal models of tumor development.

In this report, we show that the COX-2 pathway is critical for turning on the angiogenic switch during mammary cancer progression.

Materials and Methods

Animals. Generation of murine mammary tumor virus-COX-2 mice was described previously (14). Mice (monoparous or multiparous) were weaned for 3 wk before death. Animals were treated with indomethacin (Sigma, 0.75 mg/kg per day) in the drinking water during five to six multiple pregnancies (16). For nude mice studies, animals were fed with either chow or chow supplemented with 1,600 ppm (≈250 mg/kg per day) of the COX-2-selective inhibitor Celecoxib or 20 ppm (≈3 mg/kg per day) of COX-1-selective inhibitor SC-560 (17).

Tissue Preparation and Histological Analysis. Mammary glands were dissected and processed for whole-mount analysis, hematoxylin/eosin staining, and immunochemistry, as described (14).

3D Analysis of the Mammary Vasculature by Whole-Mount Lectin Staining. Multiparous nontransgenic and COX-2 transgenic mice received i.v. injections of 150 μl of 1 mg/ml FITC-conjugated tomato lectin (Lycopersicon esculentum) (Vector Laboratories), perfused with 1% formaldehyde PBS, as described (18). Mammary gland no. 4 was imaged as a whole mount on the LSM 410 Zeiss confocal microscope, and imaris 3d (Bitplane, Saint Paul, MN) software was used to analyze the images.

RNA Purification and RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from mammary tissues, and RT-PCR assays were described previously (14). The three splice variants of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiopoietin 1 (Ang1), Ang2, Flt (VEGF receptor-1), Flk (VEGF receptor-2), and (Ang receptors) Tie-2 and Tie-1 were amplified as described (19, 20). Other amplimers are: platelet–endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) 5′-agcaagaagcaggaaggac-3′ (sense), 5′-tgacaaccaccgcaatgag-3′ (antisense); GAPDH 5′-gctgagtatgtcgtggactc-3′ (sense), 5′-ttggtggtgcaggatgcatt-3′ (antisense); EP1 5′-aatacatctgtggtgctgccaaca-3′(sense), 5′-ccaccatttccacatcgtgtgcgt-3′(antisense); EP2 5′-tgcctttcacaatctttgcc-3′(sense), 5′-attccagccccttacacttc-3′(antisense); EP3 5′-ggagagactcagtgcagaaatatc-3′(sense), 5′-gaactgttagtgacacctggaatg-3′(antisense); and EP4 5′-gggagttaaaggagatcagcag3′(sense), 5′-tctagtgggagtccagatgaag-3′(antisense).

Immunoblot Analysis of Mammary Glands. Mammary glands were homogenized, and immunoblot analysis was conducted as described (14). Polyclonal antibodies for EP1–4 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI).

Determination of Microvessel Density (MVD). MVD was quantified as described after categorizing hematoxylin/eosin-stained slides following the guidelines of the Annapolis Pathology Panel (21). In terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU) counting, one continuous TDLU unit with ≈500-μm length was chosen. Only PECAM-stained vessels with lumens were counted.

Isolation of Mammary Cell Lines. Large palpable mammary tumors (≈0.5–1 cm in diameter) from murine mammary tumor virus–COX-2 transgenic mice were dissected free of surrounding mammary tissues and digested with trypsin/collagenase/dispase solution, and single-cell suspensions were plated on tissue culture dishes with 10% FBS containing DMEM. Cells were clonally purified by the dilution cloning method.

Measurement of Prostanoids by Liquid Chromatographic–Electrospray Ionization–MS (LC-ESI/MS). Mammary glands were homogenized, lipids were acidified and extracted (hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1), and eicosanoid levels were determined by LC-ESI/MS methodology as described (22). The concentrations of these prostanoids in the samples were calculated by comparing their ratios of peak areas of compounds to the internal standards with the standard curves.

Results

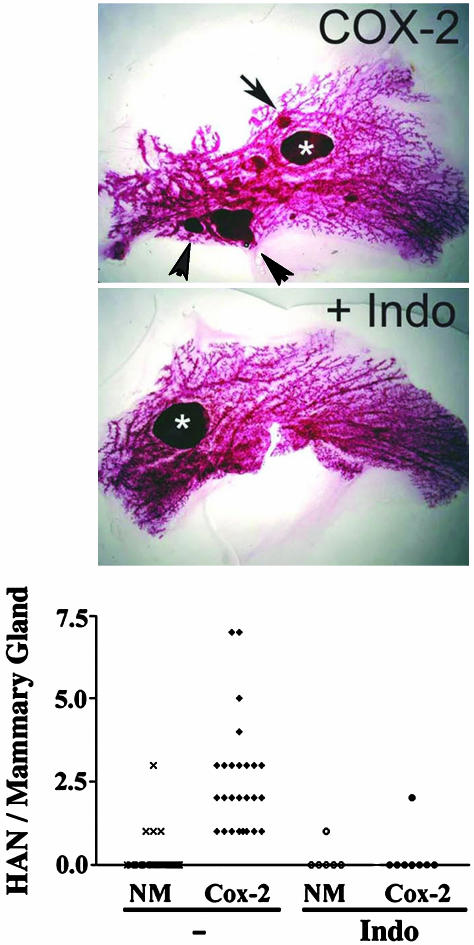

Inhibition of COX-2-Induced Mammary Tumorigenesis by Indomethacin. We first examined the effect of inhibition of prostanoid synthesis with indomethacin on mammary tumorigenesis. Analysis of whole-mount preparation of nontreated COX-2 transgenic mice shows multiple hyperplastic alveolar nodules and larger tumors (Fig. 1). When these mice were placed on indomethacin and allowed to undergo several rounds of pregnancy and lactation, tumor incidence and multiplicity were reduced. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of indomethacin treatment on tumor progression of COX-2 transgenic mice. (Top and Middle) Whole-mount analysis of mammary gland. Multiparous COX-2 mice were administered indomethacin or not, as described. Mammary glands were analyzed by whole-mount analysis and photographed under a stereomicroscope (×1). (Bottom) Tumor incidence and multiplicity are indicated in the graph. Hyperplastic alveolar nodules (HAN) in mammary gland no. 4 are counted from multiparous mice in the whole-mount preparations. Each point represents the number of HAN per animal. Number of animals = 42, 26, 6, and 8 for NM, COX-2 transgenic, NM + indomethacin (Indo), and COX-2 transgenic + indomethacin, respectively.

We analyzed the production of prostanoids in the mammary tissue of COX-2 transgenic mice by liquid chromatography MS procedures (22). As shown in Table 1, PGE2 was detected as the major metabolite. PGF2α, 6-keto-PGF1α (breakdown product of prostacyclin), PGD2, 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), 12-HETE, and 5-HETE were also detected; however, we did not detect 15-deoxy-Δ12,15-PGJ2, PGJ2, or thromboxane B2. When COX-2 transgenic mice were treated with indomethacin, prostanoid synthesis in the mammary gland was suppressed. 15-HETE, which can also be produced from the COX pathway (1), was also inhibited by indomethacin. However, 12- and 5-HETE production was not influenced by indomethacin, suggesting that they are produced from the lipoxygenase pathways.

Table 1. Tissue eicosanoid level.

| 6-keto PGF1α | PGF2α | PGE2 | PGD2 | 15-HETE | 12-HETE | 5-HETE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 0 | 1.65 ± 0.98 | 12.77 ± 3.73 | 0.20 ± 0.29 | 3.67 ± 2.00 | 3.83 ± 1.92 | 0.50 ± 0.21 |

| COX-2 | 24.87 ± 0.67 | 45.31 ± 26.87 | 173.64 ± 11.62 | 8.34 ± 5.29 | 21.85 ± 0.08 | 19.62 ± 5.65 | 1.37 ± 0.96 |

| NM + indomethacin | 0 | 0 | 1.17 ± 1.75 | 1.45 ± 1.75 | 3.82 ± 1.49 | 25.720 ± 11.56 | 0.52 ± 0.09 |

| COX-2 + indomethacin | 1.26 ± 2.18 | 0 | 1.49 ± 2.58 | 2.51 ± 2.58 | 5.25 ± 2.11 | 33.13 ± 15.46 | 0.62 ± 0.17 |

Mammary glands were excised, and eicosanoid levels were quantified by the liquid chromotographic-electrospray MS procedures, as described. Data represent values from two to three mammary glands isolated from different animals (ng per 30 mg of wet weight).

Histological analysis of mammary glands shows various stages of tumor development. Numerous early neoplastic regions were observed, for example, hyperplasia at TDLU, a precursor lesion for mammary tumorigenesis. More advanced lesions, such as ductal hyperplasia, lobular adenoma, in situ carcinoma, and invasive adenocarcinoma, were also observed (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In contrast, an indomethacin-treated multiparous mammary gland shows significantly reduced advanced neoplastic regions (Fig. 7). Only infrequent occurrence of hyperplastic TDLU was observed.

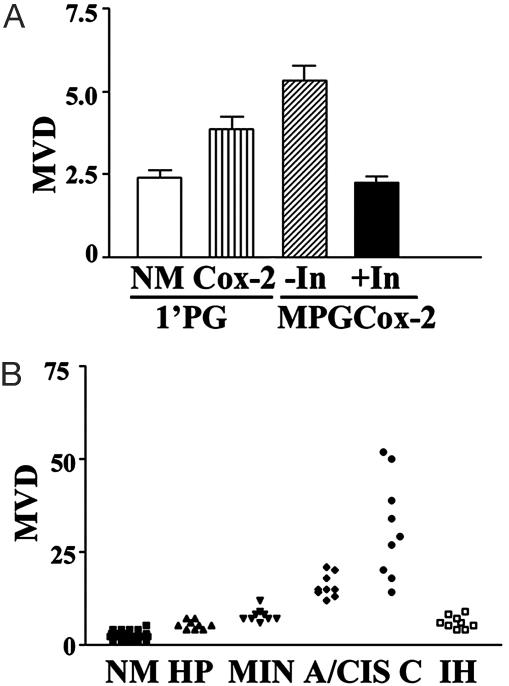

Regulation of Angiogenesis in the Mammary Gland by the COX-2 Pathway. Tumor progression requires concomitant neovessel formation (23, 24). Because COX-2 regulates tumor progression, we examined tumor-associated angiogenesis in the mammary tissue of COX-2 transgenic mice. As shown in Fig. 2A, MVD increased even in very early stages of tumor development. In the TDLU region from nontransgenic mice, small numbers of vessels were mostly found in the stroma region surrounding the ductal epithelium (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Microvessels in the TDLU region of monoparous weaned mice increased 1.7-fold in COX-2 transgenic mice compared to the nontransgenic counterparts. In the TDLU regions of the multiparous COX-2 transgenic mammary glands, MVD was increased >2-fold (Figs. 2B and 8).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of angiogenesis by indomethacin treatment in COX-2 transgenic mice. (A) Early angiogenesis in TDLU regions. Mammary glands from monoparous (1′PG) or multiparous (MPG) COX-2 transgenic mice were analyzed by immunohistochemical procedures for the endothelial marker PECAM-1, as described. In, indomethacin. n = 3. (B) PECAM immunohistochemistry of multiparous COX-2 mice treated or not with indomethacin. Data show NM, hyperplasia (HP), mammary intraepithelial neoplasia (MIN), noninvasive carcinoma in situ (A/CIS), invasive carcinoma (C), and indomethacin-treated hyperplasia (IH) lesions. Mammary glands from 15 multiparous COX-2 mice were analyzed (NM; n = 28, HP, MIN, CIS, and C; n = 9, ×40). For indomethacin-treated sections, six animals were killed (IH; n = 9, ×40).

In the early stage of tumor development in multiparous COX-2 transgenic mice, for example, hyperplastic or mammary intraepithelial neoplasia lesions, the vasculature was predominantly in the stroma near the alveolar surface (Fig. 8); however, numerous vascular arches along the edge of tumor islets in high-grade tumors, such as carcinoma in situ, were prominent. In invasive poorly differentiated tumors, numerous microvessels were scattered throughout the tumor (Fig. 8). These observations demonstrate that angiogenesis correlates with the progression of COX-2-induced mammary tumors (Fig. 2B). Indomethacin treatment strongly suppressed the development of the advanced neoplastic region and MVD (Figs. 2B and 8).

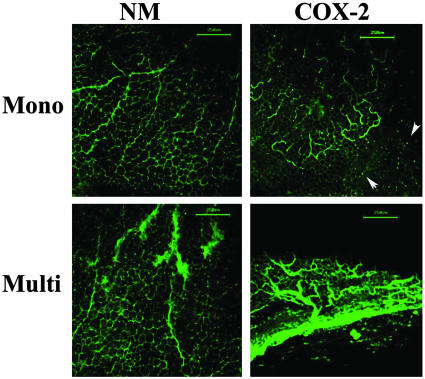

Vascular Architecture in COX-2 Transgenic Mammary Glands. To analyze the 3D morphology of the vasculature in the mammary glands of COX-2 transgenic mice, we used the whole-mount imaging procedure developed by the McDonald laboratory (18). In NM monoparous mice, the vasculature is largely composed of a honeycomb pattern of capillaries around the adipose cells and some regular-shaped larger vessels (Fig. 3). In sharp contrast, corresponding sections from COX-2 transgenic mice showed numerous vascular sprouts, arches, and loops, which is indicative of angiogenesis. In addition, numerous puncta of FITC lectin outside the vessels were observed, suggesting that the mammary vessels of COX-2 transgenic mice may be leaky (18). In multiparous COX-2 transgenic mammary glands, the vasculature contains multiple large tortuous irregular structures, reminiscent of tumor vessels. In addition, evidence of vessel leakage is also seen, as described above.

Fig. 3.

3D vascular architecture in the mammary gland of COX-2 transgenic mice. Monoparous (Mono) or multiparous (Multi) COX-2 transgenic mice were injected with fluorescently labeled lectin and perfused, and mammary glands were imaged by using the confocal fluorescence microscope; 3D images are shown. Note the presence of permeable vessels (arrowheads) and tortuous vascular sprouts and loops in COX-2 transgenic mammary glands. (Bar = 250 μm.)

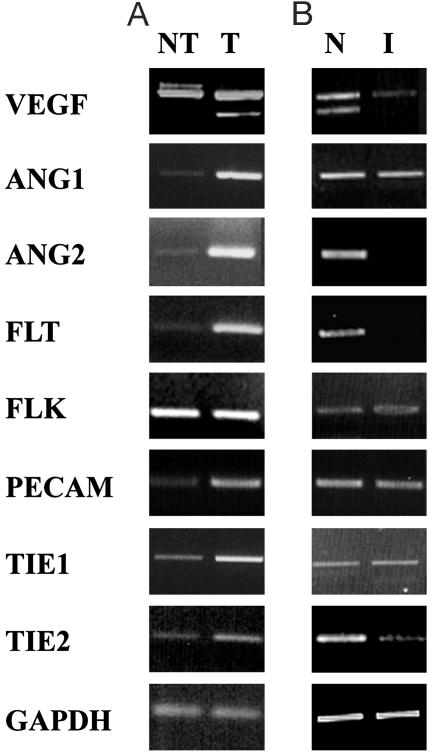

Regulation of Angiogenic Regulatory Genes by the COX-2 Pathway. We analyzed the level of expression of mRNAs for angiogenic regulatory molecules by RT-PCR assay with RNA isolated from tumor and nontumor regions of multiparous COX-2 transgenic mice. As shown in Fig. 4, significant induction of VEGF120 mRNA isoform, Ang1, Ang2, Flt, and Tie-2 was observed. Indomethacin treatment in multiparous COX-2 transgenic mice suppressed the expression of VEGF120, Flt, Ang2, and Tie-2 but not Ang1, Flk, or Tie-1.

Fig. 4.

Regulation of angiogenic-regulatory genes by the COX-2 pathway. RNA was isolated from nontumor (NT) and tumor (T) regions in multiparous COX-2 mice (A) and from nontreated (N) and indomethacin-treated (I) multiparous COX-2 mice (B). Expression of VEGF, Ang1, Ang2, Flt, Flk, Tie-1, and Tie-2 was analyzed by RT-PCR analysis.

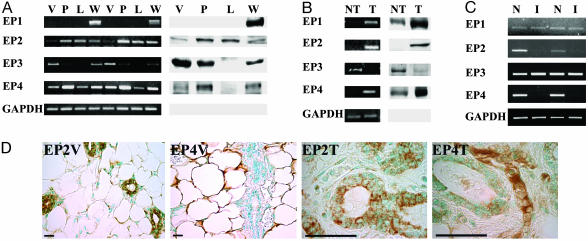

PGE2 Receptors in Mammary Gland Development and Tumorigenesis. We next examined the expression of PGE receptors and EP1–4 in NM development and tumorigenesis of the mammary gland. As shown in Fig. 5A, EP2 and EP4 receptors are induced during the proliferative phase of mammary-gland development (pregnancy and lactation) and subsequently down-regulated during the involution phase. EP3 is down-regulated during the proliferative stage of mammary gland development, and its expression is returned to high levels in the involuted mammary gland. In contrast, the EP1 receptor is expressed only in the involuted mammary gland.

Fig. 5.

PGE2 receptors in mammary gland tumorigenesis. (A) Expression of EP1–4 receptors during mammary gland development. Mammary tissues from virgin (V, 16 wk), pregnant (P, 18 days pregnant), lactating (L, 7 days postpartum), and weaning (W, 14 days postweaning) mice were used to purify RNA for RT-PCR analysis and protein for Western blot analysis, as described. (B) Expression of EP1–4 receptors in mammary tumors from COX-2 transgenic mice. RNA and protein were isolated from nontumor (NT) and tumor (T) regions and followed by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis, as described. (C) Modulation of EP receptors by indomethacin treatment. Nontreated (N) and indomethacin-treated (I) mammary glands from multiparous COX-2 mice were used for RT-PCR analysis, as described. (D) Cellular localization of EP2,4 receptors. Mammary glands of nontransgenic virgin mice (V) were analyzed by immunohistochemical procedures for expression of EP2,4 antigens (×40). Mammary tumor (T) in COX-2 transgenic mice, identified as an adenoma by hematoxylin/eosin staining, was used to examine localization for EP2,4 receptors (×100). (Bar = 50 μm.)

In COX-2-induced mammary tumors, EP1,2,4 receptors are strongly induced, whereas the EP3 receptor is down-regulated (Fig. 5B). Indomethacin-treated mice expressed reduced levels of EP2,4 receptors in mammary glands, whereas the levels of EP1 and EP3 were not altered (Fig. 5C).

Immunohistochemical analysis indicates that the EP2 subtype was expressed by ductal and alveolar epithelial cells in the mammary gland and was strongly induced in the mammary adenoma cells (Fig. 5D). EP2 receptor expression was not detected in adipocytes and vascular endothelial cells or smooth muscle cells of the mammary gland. In sharp contrast, strong EP4 expression was primarily associated with mesenchymal compartments; namely, stromal cells, adipocytes, and hematopoietic cells with no expression in ductal and alveloar epithelial cells. Low but detectable expression was also seen in the endothelial cells of the microvasculature (Fig. 5D). However, in the COX-2-induced mammary tumor, the EP4 receptor is expressed strongly in hematopoietic as well as endothelial cells and weakly in adenoma cells.

Tumor Angiogenesis in Nude Mouse Models of Mammary Tumor Cells. To define the causal relationships involved in COX-2 expression, PGE2 synthesis/action, and tumor angiogenesis, we derived clonal cell lines from established tumors of COX-2 transgenic mammary glands. One such cell line has myoepithelial characteristics (25), because it expresses α smooth muscle actin and N- but not E-cadherin. In addition, endogenous murine COX-2 and transgenic human COX-2 are also expressed (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). It also exhibits properties of transformed cells, such as loss of contact inhibition, ability to proliferate in the absence of serum, and ability to grow in an anchorage-independent manner (data not shown). RT-PCR analysis indicated that all four EP receptors (EP1–4) are expressed in vitro (Fig. 9).

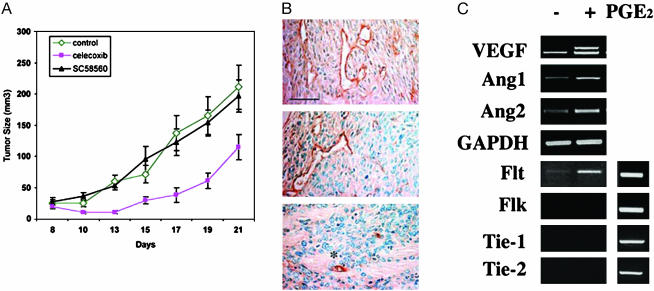

When implanted s.c. in nude mice, mammary tumor cells grew rapidly as tumors (Fig. 6A). When COX-2 was inhibited with Celecoxib, tumor growth was strongly suppressed, whereas the COX-1-specific inhibitor SC-560 did not influence tumor growth. Histological analysis of microvessels (Fig. 6B) shows that Celecoxib-treated tumors exhibit reduced density of tumor microvasculature, collapse of microvessels, and enhanced tumor cell necrosis/apoptosis. The COX-1-selective inhibitor SC-560 did not significantly affect tumor microvessels. Treatment with PGE2 in vitro strongly induced the expression of angiogenic regulatory factors VEGF164, Ang1, and Ang2. Interestingly, the Flt-1/VEGFR-1 receptor is also expressed in these cells and induced by 1 μM PGE2 treatment, but no expression or induction of Flk, Tie-1, and Tie-2 was observed. These data strongly suggest that tumor cell-derived COX-2 profoundly influences tumor angiogenesis and thereby modulates tumor growth in vivo.

Fig. 6.

Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by PGE2 in cultured mammary tumor cells. (A) COX-2 is required for tumor growth in athymic nude mice. Mammary tumor cells (106) were injected s.c. into nude mice. After 1 wk of injection, mice were placed on the control diet or SC-560-(COX-1-specific inhibitor) or Celecoxib-supplemented (COX-2-specific inhibitor) diets. Tumor volume was measured as described (n = 5–6 per treatment). (B) Tumors from treated or untreated nude mice were dissected and analyzed by immunohistochemical procedures for PECAM-1, as described. Note that microvessels were less numerous and exhibited patterns of apoptosis (asterisks). The tumor section also showed evidence of necrosis and apoptosis (condensed nuclei). (Bar = 50 μm.) (Top) Control; (Middle) SC58560; (Bottom) Celecoxib. (C) Induction of angiogenesis regulatory genes by PGE2 treatment. Cells were starved for 24 h in the presence of indomethacin (5 μM) and treated with 1 μM PGE2 for 1 h. RNA was isolated, and RT-PCR was conducted for the indicated genes. (Right) Flt and Flk; Tie-1 and -2 are positive controls.

Discussion

Data in this report show that the enzymatic activity of COX-2 is critical for the induction of tumorigenic transformation. Administration of indomethacin (≈0.75 mg/kg) potently suppressed prostanoid synthesis and inhibited tumorigenesis and tumor-associated angiogenesis. Indomethacin is a nonselective COX-1 and -2 inhibitor, and therefore we cannot rule out the participation of the endogenous COX-1 enzyme in the tumorigenesis and angiogenesis process. Nevertheless, at the dose used, indomethacin primarily affects prostanoid synthesis, and non-COX targets are unlikely to be involved (16, 26). However, COX-1 by itself is not sufficient to induce tumors (14). The major prostanoid produced by the mammary gland is PGE2, suggesting that it is important in the angiogenic and tumorigenic effects (11). Indeed, PGE2 is a potent inducer of angiogenesis in vivo and induces the expression of angiogenic regulatory proteins such as VEGF (27, 28).

Histological analysis of mammary tumors induced in COX-2 transgenic mice indicated that the entire spectrum of tumor development was observed. In particular, we observed hyperplastic TDLU, mammary intraepithelial neoplasia, adenocarcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma (21). Treatment of COX-2 transgenic mice with indomethacin inhibited the formation of advanced lesions (both incidence and multiplicity), and only limited hyperplastic lesions were observed, suggesting that COX-2 plays an important role in tumor progression in this transgenic model.

The progression of a localized tumor into an invasive cancer requires the activation of the so-called “angiogenic switch” (29). In molecular terms, this translates to the exaggerated expression and/or export of proangiogenic factors and/or down-regulation of antiangiogenic mediators. Our data suggest that COX-2 overexpression is a component of the angiogenic switch, and that COX-2 regulates this even before the induction of epithelial hyperplasia. Enhanced angiogenesis was seen early but is also sustained. These data provide a molecular explanation for early observations showing that the angiogenic capacity of preneoplastic mammary lesions predicted subsequent transformation into cancer in both murine and human systems (23, 30).

3D confocal imaging of the microvasculature from COX-2 transgenic mice clearly confirmed the histological analysis of MVD and provided additional clues to the regulation of the vascular system by the COX-2 pathway. Enhanced formation of vascular loops and arches indicated early and robust activation of the angiogenesis process. In addition, evidence of abnormal vessel function, most likely due to enhanced vascular permeability, was observed. It is known that enhanced leakage of microvessels is an early prerequisite event in the induction of angiogenic response induced by growth factors such as VEGF (31, 32). In multiparous involuted mammary glands, abnormally tortuous vascular structures were seen, indicating that dysregulated COX-2 expression induces a tumor vessel-like phenotype (33) in the mammary gland vasculature.

Because angiogenesis is brought about by the action of angiogenic regulatory factors, we analyzed the expression of mRNAs for potent angiogenic factors, VEGF, Ang1, Ang2, and their receptors. Multiparous mammary glands from COX-2 transgenic mice, which contain tumors, contain exaggerated levels of mRNA for VEGF, Ang1, Ang2, Flt [VEGF-1 receptor (VEGFR-1)], Flk (VEGFR-2), Tie 2, and Tie1. Importantly, indomethacin treatment reduced these transcripts, suggesting that the COX-2 pathway is capable of regulating the expression of potent angiogenesis regulators. It is known that VEGF induces vascular permeability and angiogenesis (31), thus VEGF is likely to be important in the vascular changes observed in the mammary glands of COX-2 transgenic mice.

EP receptor expression studies indicate that all four subtypes are expressed in different stages of mammary gland development. Interestingly, EP2,4 subtypes are expressed in proliferating mammary glands during pregnancy and also in mammary tumors. Indomethacin treatment suppressed expression of EP2,4 receptor subtypes, suggesting that these two receptors are likely to be involved in the regulation of mammary tumor progression and angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry of tissue sections indicates that EP2 is likely important in the epithelial cell compartment, whereas EP4 is highly expressed in stromal and hematopoietic cells. Both receptors are coupled to the heterotrimeric Gs protein and regulate the cAMP/protein kinase-A pathway. EP2 receptor function was shown to be critically important in the regulation of intestinal polyp-induced angiogenesis in the ApcΔ716 model of neoplasia (28, 34). In addition, EP4 receptor activation was shown to be important in PGE2-induced morphologic changes and invasive behavior in colorectal tumor cells in vitro (35). Our data suggest that COX-2 in the epithelial compartment signals via the EP2 receptor in an autocrine manner and via the EP4 receptor in a paracrine manner.

To directly show that PGE2 signaling is important in angiogenesis, we treated mammary tumor-derived cells in vitro with 1 μM PGE2, which resulted in strong induction of VEGF, Ang1, -2, and Flt/VEGFR-1. However, in this cell system, only the cell-associated VEGF164 splice isoform is induced. Importantly, tumorigenic growth of these cell lines required COX-2 activity. In COX-2-inhibitor-treated tumors, microvessels were necrotic/apoptotic, concomitant with tumor necrosis and reduced growth rate. These data strongly suggest that PGE2 secreted by COX-2-expressing mammary tumor cells induces tumor progression at least in part by inducing angiogenic regulatory factors.

In conclusion, our data show that COX-2 profoundly regulates tumor progression by secretion of prostanoids, in particular the major product, PGE2. The EP2,4 subtypes of PGE2 receptors are expressed in epithelial and stromal cellular compartments, which constitute autocrine and paracrine models of signaling. Angiogenic regulatory genes, VEGF, Ang1, Ang2, Flt/VEGFR-1, and Tie 1 and -2, are induced by the COX-2 pathway, resulting in dramatic changes in the structure and function of mammary gland vasculature. These data provide, in part, the molecular basis of how COX-2 transforms the mammary gland into a tumorigenic state. Identification of such molecular targets and mechanisms may aid in the rational design of chemopreventive as well as treatment regimens using COX-2-selective inhibitors in mammary cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard Breyer for critical comments on EP receptors, Drs. Kevin Claffey and Luisa Iruela-Arispe for help with vascular whole-mount imaging, and Dr. Ann Cowan for help with confocal microscopy and image analysis. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA95181 (to T.H.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: COX, cyclooxygenase; PG, prostaglandin; MVD, microvessel density; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; TDLU, terminal ductal lobular unit; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR, VEGF receptor; Ang, angiopoietin; PECAM, platelet–endothelial cell adhesion molecule; NM, normal.

See Commentary on page 415.

References

- 1.Smith, W. L., DeWitt, D. L. & Garavito, R. M. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 145–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hla, T., Bishop-Bailey, D., Liu, C. H., Schaefers, H. J. & Trifan, O. C. (1999) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 31, 551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thun, M. J. (1996) Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 25, 333–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta, R. A. & Dubois, R. N. (2001) Nat. Rev. Cancer 1, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taketo, M. M. (1998) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 1529–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao, C. V., Rivenson, A., Simi, B., Zang, E., Kelloff, G., Steele, V. & Reddy, B. S. (1995) Cancer Res. 55, 1464–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masferrer, J. L., Leahy, K. M., Koki, A. T., Zweifel, B. S., Settle, S. L., Woerner, B. M., Edwards, D. A., Flickinger, A. G., Moore, R. J. & Seibert, K. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 1306–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oshima, M., Dinchuk, J. E., Kargman, S. L., Oshima, H., Hancock, B., Kwong, E., Trzaskos, J. M., Evans, J. F. & Taketo, M. M. (1996) Cell 87, 803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ristimaki, A., Sivula, A., Lundin, J., Lundin, M., Salminen, T., Haglund, C., Joensuu, H. & Isola, J. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 632–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris, R. E., Namboodiri, K. K. & Farrar, W. B. (1996) Epidemiology 7, 203–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris, R. E., Alshafie, G. A., Abou-Issa, H. & Seibert, K. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 2101–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howe, L. R., Subbaramaiah, K., Patel, J., Masferrer, J. L., Deora, A., Hudis, C., Thaler, H. T., Muller, W. J., Du, B., Brown, A. M., et al. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 5405–5407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards, J. A. & Brueggemeier, R. W. (2003) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 2810–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, C. H., Chang, S. H., Narko, K., Trifan, O. C., Wu, M. T., Smith, E., Haudenschild, C., Lane, T. F. & Hla, T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18563–18569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller-Decker, K., Neufang, G., Berger, I., Neumann, M., Marks, F. & Furstenberger, G. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12483–12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silver, R. M., Edwin, S. S., Trautman, M. S., Simmons, D. L., Branch, D. W., Dudley, D. J. & Mitchell, M. D. (1995) J. Clin. Invest. 95, 725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peebles, R. S., Jr., Hashimoto, K., Morrow, J. D., Dworski, R., Collins, R. D., Hashimoto, Y., Christman, J. W., Kang, K. H., Jarzecka, K., Furlong, J., et al. (2002) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165, 1154–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurston, G., Baluk, P., Hirata, A. & McDonald, D. M. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271, H2547–H2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hovey, R. C., Goldhar, A. S., Baffi, J. & Vonderhaar, B. K. (2001) Mol. Endocrinol. 15, 819–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, Y., Wada, R., Yamashita, T., Mi, Y., Deng, C. X., Hobson, J. P., Rosenfeldt, H. M., Nava, V. E., Chae, S. S., Lee, M. J., et al. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 106, 951–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardiff, R. D., Anver, M. R., Gusterson, B. A., Hennighausen, L., Jensen, R. A., Merino, M. J., Rehm, S., Russo, J., Tavassoli, F. A., Wakefield, L. M., et al. (2000) Oncogene 19, 968–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nithipatikom, K., Laabs, N. D., Isbell, M. A. & Campbell, W. B. (2003) J. Chromatogr. B 785, 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brem, S. S., Gullino, P. M. & Medina, D. (1977) Science 195, 880–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heffelfinger, S. C., Miller, M. A., Yassin, R. & Gear, R. (1999) Clin. Cancer Res. 5, 2867–2876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazard, D., Sastre, X., Frid, M. G., Glukhova, M. A., Thiery, J. P. & Koteliansky, V. E. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 999–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lala, P. K., Al-Mutter, N. & Orucevic, A. (1997) Int. J. Cancer 73, 371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ben-Av, P., Crofford, L. J., Wilder, R. L. & Hla, T. (1995) FEBS Lett. 372, 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seno, H., Oshima, M., Ishikawa, T. O., Oshima, H., Takaku, K., Chiba, T., Narumiya, S. & Taketo, M. M. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 506–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanahan, D. & Folkman, J. (1996) Cell 86, 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gimbrone, M. A., Jr., & Gullino, P. M. (1976) Cancer Res. 36, 2611–2620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dvorak, H. F. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 162, 1747–1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yancopoulos, G. D., Davis, S., Gale, N. W., Rudge, J. S., Wiegand, S. J. & Holash, J. (2000) Nature 407, 242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morikawa, S., Baluk, P., Kaidoh, T., Haskell, A., Jain, R. K. & McDonald, D. M. (2002) Am. J. Pathol. 160, 985–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sonoshita, M., Takaku, K., Sasaki, N., Sugimoto, Y., Ushikubi, F., Narumiya, S., Oshima, M. & Taketo, M. M. (2001) Nat. Med. 7, 1048–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheng, H., Shao, J., Washington, M. K. & DuBois, R. N. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18075–18081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.