Abstract

Chitin, a highly insoluble polymer of GlcNAc, is produced in massive quantities in the marine environment. Fortunately for survival of aquatic ecosystems, chitin is rapidly catabolized by marine bacteria. Here we describe a bacterial two-component hybrid sensor/kinase (of the ArcB type) that rigorously controls expression of ≈50 genes, many involved in chitin degradation. The sensor gene, chiS, was identified in Vibrio furnissii and Vibrio cholerae (predicted amino acid sequences, full-length: 84% identical, 93% similar). Mutants of chiS grew normally on GlcNAc but did not express extracellular chitinase, a specific chitoporin, or β-hexosaminidases, nor did they exhibit chemotaxis, transport, or growth on chitin oligosaccharides such as (GlcNAc)2. Expression of these systems requires three components: wild-type chiS; a periplasmic high-affinity chitin oligosaccharide, (GlcNAc)n (n > 1), binding protein (CBP); and the environmental signal, (GlcNAc)n. Our data are consistent with the following model. In the uninduced state, CBP binds to the periplasmic domain of ChiS and “locks” it into the minus conformation. The environmental signal, (GlcNAc)n, dissociates the complex by binding to CBP, releasing ChiS, yielding the plus phenotype (expression of chitinolytic genes). In V. cholerae, a cluster of 10 contiguous genes (VC0620–VC0611) apparently comprise a (GlcNAc)2 catabolic operon. CBP is encoded by the first, VC0620, whereas VC0619–VC0616 encode a (GlcNAc)2 ABC-type permease. Regulation of chiS requires expression of CBP but not (GlcNAc)2 transport. (GlcNAc)n is suggested to be essential for signaling these cells that chitin is in the microenvironment.

Two-component signal transduction systems (also known as His–Asp phosphorelay systems) play essential roles in transferring information from the environment to the respective genomes of prokaryotes and some eukaryotes (1, 2). There are at least 29 His kinase signal transduction systems in Escherichia coli. In this article we report that two marine Vibrios, Vibrio furnissii and Vibrio cholerae express a unique two-component signaling system that stringently regulates expression of many genes required for chitin catabolism.

Chitin is a highly insoluble β,1-4-linked polymer composed primarily of GlcNAc and some glucosamine (GlcN) residues and is one of the most abundant organic substances in nature. More than 1011 tons are estimated to be produced annually in marine waters alone, mostly from copepods. The consumption of these huge quantities of chitin is critical for maintaining the C and N cycles in these waters. It is, in fact, rapidly consumed. Early in the last century it was shown that ocean sediments contained only traces of chitin despite the constant rain of the polysaccharide (“marine snow”) to the ocean floor. This apparent enigma was resolved in 1937 when Zobell and Rittenberg (3) reported that many marine bacteria were chitinivorous, i.e., they could use chitin as the sole source of C and N, and it has since been shown that marine snow rarely reaches the ocean bottom but is degraded as it slowly settles in the ocean waters.

The degradation process is exceedingly complex (partially reviewed in ref. 4). The cells must sense the chitin, bind to it, and degrade it to fructose-6-P, acetate, and NH3. We estimated that the overall chitin catabolic cascade involved dozens of enzymes and structural proteins. These include at least one, and probably several, extracellular chitinases, chemotaxis systems specific for chitin oligosaccharides (highly potent chemoattractants), a “nutrient sensor” that allows the cells to bind to the chitin as long as the extracellular environment contains all ingredients necessary for protein synthesis, a specific chitoporin in the outer membrane, at least two hydrolases specific for chitin oligosaccharides in the periplasmic space that yield the monosaccharide (GlcNAc) and the disaccharide (GlcNAc)2, respectively, three transport complexes in the inner membrane, and a minimum of six cytoplasmic enzymes that convert the products of transport to fructose-6-P, NH3, and acetate. We have reported the molecular cloning of 10 of these genes and characterized the corresponding proteins (5–13).

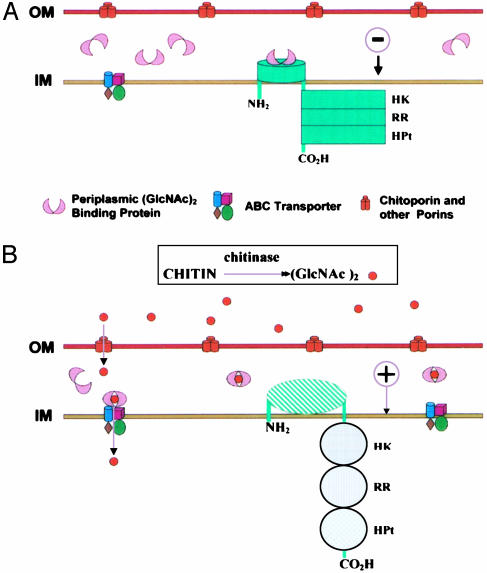

Expression of the chitinolytic genes is rigorously regulated, and the proposed mechanism for this regulation is shown in Fig. 1. The model comprises three components: (i) the environmental signal, (GlcNAc)2, and possibly higher chitin oligosaccharides; (ii) a periplasmic solute binding protein specific for (GlcNAc)n (n > 1) designated here as CBP for chitin oligosaccharide binding protein; and (iii) a hybrid sensor kinase of the Arc B type (14), designated ChiS. In sensors of this kind, the protein consists of a short N-terminal peptide chain in the cytoplasm, a membrane domain, a periplasmic domain, a second membrane domain, and a long polypeptide chain extending into the cytoplasm. The latter comprises three subdomains: HK or His kinase, RR or receiver (aspartate), and HPt. The phosphoryl group is transferred sequentially from ATP to HK, to RR, to a His in HPt, and finally to Asp in a separate cytoplasmic cognate response regulator that interacts with the genome (not shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Model for regulation of activity of the chitin catabolic sensor ChiS in V. furnissii and V. cholerae. (A) The minus phenotype. Three compartments, separated by two membranes are schematically illustrated: the extracellular space, the periplasmic space, and the cytoplasm. The outer membrane (OM) contains the porins, including a chitin oligosaccharide specific porin (chitoporin). The periplasmic space contains the (GlcNAc)n high-affinity binding protein (CBP) shown in pink. ChiS, the hybrid sensor, is green, and contains the following domains: short amino terminal cytoplasmic domain, a periplasmic domain that separates two short membrane domains, and a large cytoplasmic domain comprising three subdomains: HK, the ATP-dependent, autophosphorylatable His kinase/phosphatase; RR, the Asp response regulator; and HPt, which contains a phosphorylatable His. The presumptive cognate receptor, a separate protein containing an active site Asp, is not shown. The inner membrane (IM) also contains the (GlcNAc)2 ABC type permease. The periplasmic binding protein binds to ChiS, locking it into an inactive conformation, resulting in repression of the chitinolytic genes. (B) The plus phenotype. Extracellular chitinase(s) hydrolyze the polymer to oligosaccharides, the major product being (GlcNAc)2. The oligosaccharides enter the periplasmic space and bind to CBP, dissociating it from ChiS, which is now transformed into the active (+) conformation. The chitinolytic genes are now expressed.

We propose that repression of expression of the chitinolytic genes, the minus phenotype, is the result of binding of the (GlcNAc)n periplasmic binding protein to the periplasmic domain of the sensor, “locking” it into an inactive conformation (Fig. 1 A). The environmental signals are chitin oligosaccharides derived from partial hydrolysis of chitin by chitinases. In Fig. 1B, (GlcNAc)2 is used as the example because it is the major product formed by virtually all bacterial and many eukaryotic chitinases. In addition, two enzymes in the periplasmic space hydrolyze higher oligosaccharides to (GlcNAc)2 and some GlcNAc (9, 10). CBP does not bind the monosaccharide, GlcNAc.

The extracellular signals, (GlcNAc)2 or, more generally, (GlcNAc)n, compete with the sensor ChiS for CBP. ChiS cannot bind the CBP/(GlcNAc)n complex and is thereby activated to the plus phenotype (Fig. 1B), whereon the chitinolytic genes are expressed.

Materials and Methods

Materials. The following chemicals, reagents, and materials were purchased from the indicated sources. p-nitrophenyl β-d-N-acetylglucosaminide (PNP-GlcNAc) was from Sigma; Hepes buffer was from Fisher; oligonucleotide primers were from IDT (Coralville, IA); chitin oligosaccharides (GlcNAc)n, n = 2–6, were prepared as described (15) or were from Seikagaku (Rockville, MD); DNA restriction and modifying enzymes were from New England Biolabs; and pGEM-T Vector System I was from Promega. Other buffers and reagents were of the highest purity commercially available.

Growth and Maintenance of V. cholerae Strains. V. cholerae cells were grown either in LB containing 1% NaCl or minimal media containing 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 50% artificial sea water (ASW), 0.1% NH4Cl, 0.001% K2HPO4, and 0.5% dl-lactate (lactate-ASW). Cell cultures were grown at 37°C with aeration (30°C for V. furnissii) and growth measured by absorbance at 540 nm. (GlcNAc)2 was added at 0.6 mM in the minimal medium for induction of the β-hexosaminidases. The concentrations of antibiotics were 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 75 μg/ml ampicillin.

Construction of Mutants. DNA preparation and analysis, restriction enzyme digests, ligation, and transformations were performed according to standard techniques (16). A Tn10 mutant library was constructed by transconjugation with V. furnissii strain ATCC 33813 as recipient and E. coli S17-1 harboring a suicide plasmid containing the Tn10 transposon with a chloramphenicol resistance gene derived from pNK2884 (17) as donor. The concentrations of antibiotics were 10 μg/ml ampicillin and 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol.

V. cholerae deletion mutants were constructed by transconjugation (18) with a temperature-sensitive suicide vector, pMAKSACA. V. cholera O1 E1 Tor N16961 strains with ΔscrAΔlacZ, KanR (VCXB21, wild type) or ΔscrAΔlacZ (VCXB36, wild type) were used as parental strains, and E. coli S17-1 cells harboring appropriate deletion vectors were used as donor strains. (i) CBP deletion strain: The EcoRI to SnaBI fragment of the cbp gene (VC0620) was deleted (373 of 556 aa; residues 43–416) and replaced with a kanamycin resistance cassette from plasmid pNK2859 (17). VCXB36 was used as the recipient strain. (ii) chiS deletion strain and chiSΔcbpΔ double-deletion strain: The chiS deletion strain contains fragments of the N and C termini of chiS, 48 and 50 bp, respectively, interrupted by a BglII restriction site. This construct was transferred to VCXB21 as the recipient. The chiSΔcbpΔ double-deletion strain contains an additional AmpR (from pBR322) in the BglII site of the chiS deletion construct, using cbpΔ as the recipient. (iii) CBP-positive, permease deletion strain (VC0616–VC0619Δ): The mutant contains 311 bp of the N terminus of VC0619, a BglII site, followed by 329 bp at the C terminus of VC0616. A kanamycin resistance cassette from pNK2859 was inserted into the BglII site. VCXB36 was used as the recipient strain.

β-Hexosaminidase Assay. These enzymes were assayed with PNP-GlcNAc as described (10). In brief, V. cholerae cells were grown in the minimal lactate-ASW medium to mid-log phase, the cell density was adjusted to 5 × 108 cells per ml, and the cells were treated with toluene at a ratio of 10 μl/ml of suspension. After vigorous shaking for 10 sec, the mixture was maintained at room temperature for 20 min, and 0.1-ml aliquots were mixed with 0.1 ml of 1 mM PNP-GlcNAc in 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5) and incubated at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with 0.8 ml of 1 M Tris base (pH 11), cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the absorbance of the supernatant was determined at 400 nm. Total hexosaminidase activity is expressed as p-nitrophenol produced per minute per mg of protein.

Results

Isolation of Sensor Mutants from V. furnissii. A transposon Tn10 mutant library was constructed in V. furnissii by transconjugation, and the desired mutants were enriched by growing the cells on a lethal analogue of (GlcNAc)2, i.e., (GlcNHCOCF3)2. They were spread on chitin plates, and colonies that could not clear the chitin (negative chitinase expression) were selected for further study. Three of 6,000 transposon mutants showed the desired phenotypes. First and most importantly, they fermented and grew at normal rates on the monosaccharide, GlcNAc. Second, they could not be induced to express a number of proteins required for chitin degradation. DNA sequence analysis of the three mutants showed that Tn10 had inserted into three different regions of the same gene, designated the chitin degradation sensor (chiS) gene.

Relationship Between V. furnissii and V. cholerae. When the complete sequence of the V. cholerae genome became available (19), we found a surprising similarity between the predicted amino acid sequences of many V. cholerae gene products and those that we had cloned and characterized from V. furnissii. Table 1 summarizes these findings. The predicted amino acid sequences of 7 of 10 putative gene products are ≥70% identical, and ≥76% similar over the full length of the proteins. The subjects of this report, the sensor proteins, are 84% identical and 93% similar. Table 1 also gives the correct functional assignment to each of the gene products.

Table 1. Comparison of predicted amino-acid sequences of proteins from V. furnissii and V. cholerae.

| V. furnissii proteins | V. cholerae ORF (annotation) | Identity, % | Similarity, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| (GlcNAc)2 phosphorylase | VC0612 (cellobiose phosphorylase) | 86 | 92 |

| chiS (sensor) | VC0622 (sensor) | 84 | 93 |

| Aryl β-N-acetylglucosaminidase | VC0692 (β-hexosaminidase) | 81 | 90 |

| Periplasmic β-N-acetylglucosaminidase | VC0613 (β-hexosaminidase) | 76 | 86 |

| Periplasmic chitodextrinase | VCA0700 (chitodextrinase) | 76 | 82 |

| Glucosamine-specific kinase | VC0614 (hypothetical protein) | 75 | 82 |

| Extracellular chitinase | VCA0027 (chitinase) | 75 | 83 |

| Cellobiase (exoglucosidase) | VC0615 (endoglucanase) | 70 | 77 |

| Chitoporin | VC0972 (porin, putative) | 49 | 60 |

| NagE (IIGlcNAc) transporter | VC0995 (IIGlcNAc) transporter | 42 | 55 |

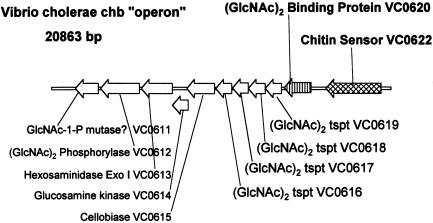

A Potential N,N′-diacetylchitobiose Operon in V. cholerae. An important relationship between the (GlcNAc)2 genes is also apparent in Table 1, i.e., that four of the genes, VC0612–VC0615, are clustered together in the V. cholerae genome. This region of the genome is shown in Fig. 2, and the cluster of the four genes are part of 10 contiguous genes, from VC0611 to VC0620. VC0616–VC0620 encodes an ABC-type transporter specific for (GlcNAc)2 and possibly (GlcNAc)3. We have described the kinetic behavior of this transporter (8). We therefore conclude that 8 of the 10 genes are required for (GlcNAc)2 uptake and catabolism, 1 gene (VC0611) is annotated as a phosphohexose mutase, although we believe that it is likely to be a phospho-GlcNAc mutase, and the 10th gene, VC0615, has been shown to encode a cellobiase (13) whose physiological function is unknown. (V. cholerae neither grows on nor ferments cellobiose.) Evidence shows that the 10 genes function as a (GlcNAc)2 catabolic operon (unpublished work).

Fig. 2.

Putative V. cholerae (GlcNAc)2 catabolic operon. The two highlighted genes, VC0620 and VC0622, are the subjects of this communication. The “operon” consists of 10 genes, VC0620–VC0611. VC0622 (chiS) must be expressed for these genes to be derepressed. The annotations of five genes are based on biochemical characterization of the proteins purified to apparent homogeneity, and of the phenotypes of mutants: VC0615 (13), VC0614 (12), VC0613 (10), and VC0612 (11). The binding protein, VC0620, has been purified to homogeneity and its binding properties have been established by equilibrium and/or flow dialysis (unpublished work). The four-gene cluster VC0619–VC0616 is an ABC-type (GlcNAc)2 transporter based on the phenotypic behavior of mutants in any or all of the genes [no transport of the analogue MeTCB (8)]. The assignment of VC0611 as a GlcNAc-1-P mutase is speculative. The following annotations were previously assigned to these genes in the V. cholerae genomic sequence (19): VC0622, sensor; VC0620, periplasmic binding protein; VC0619–VC0616, polypeptide ABC-type transporter; VC0615, endoglucanase; VC0614, hypothetical protein; VC0613, β-N-acetylglucosaminidase; VC0612, cellobiose phosphorylase; VC0611, phosphohexose mutase. One short ORF (130 aa predicted) in the V. cholerae genome sequence, VC0621, annotated as “hypothetical protein,” is not shown because it is not found in any other known Vibrio genomic sequence or in V. furnissii.

Chitin Degradation Sensor. VC0620 is the first structural gene in the presumptive “chitobiose,” more correctly, the N,N′-diacetylchitobiose or (GlcNAc)2 catabolic operon. Upstream (917 bp) is VC0622, the structural gene for chiS. The sensor mutants isolated as described above showed the following phenotypic properties. They did not clear chitin plates (4); i.e., they did not express the extracellular chitinase at normal levels. Additionally, they did not express the chitoporin (7), uptake of MeTCB, which is transported by the (GlcNAc)2 permease (8), β-N-acetylhexosaminidases (see below), or chemotaxis to chitin oligosaccharides (20). Finally, they neither fermented nor grew on (GlcNAc)2, whereas they grew normally on GlcNAc. When the V. cholerae and V. furnissii mutants were complemented with the respective intact genes, the defective functions were restored, although not necessarily to wild-type levels.

The Periplasmic Chitin Oligosaccharide Binding Protein (CBP). If the model shown in Fig. 1 is correct, the sensor is “locked” in the negative mode when it is held in this conformation by bound CBP. The periplasmic binding protein CBP has been purified to apparent homogeneity and is a CBP with a Kassoc for (GlcNAc)2 of ≈1 μm. This constant is similar to the association constants of periplasmic sugar binding proteins (21, 22). CBP also binds higher chitin oligosaccharides (but not GlcNAc); these binding constants remain to be determined.

Assay of Cells for Total β-N-Acetylglucosaminidase Activity. Although many processes are regulated by the sensor, for present purposes we chose to study the total exo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity by using the generic substrate for these enzymes, PNP-GlcNAc. This compound is an excellent substrate for three well characterized exo-β-hexosaminidases in the two Vibrios. These glycosidases are induced by (GlcNAc)2 and have been identified in the V. cholerae genome: VC2217, an outer membrane bound β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (23); VC0613, a periplasmic enzyme specific for chitin oligosaccharides (10); and VC0692, an aryl β-N-acetylglucosaminidase of unknown function (6). Six other genes in the sequence are annotated as putative chitinases or chitodextrinases; it seems likely that some of these may also be exorather than endohydrolases, in which case they would split the generic substrate PNP-GlcNAc. (For instance, VC0615 is annotated as an endoglucanase, such as cellulase, but it is an exo-β-glucosidase (13).) The advantage of using the generic substrate is that the genes are scattered over the two V. cholerae chromosomes, and quantitation of total enzymatic activity is a measure of the global effect of the sensor on these genes.

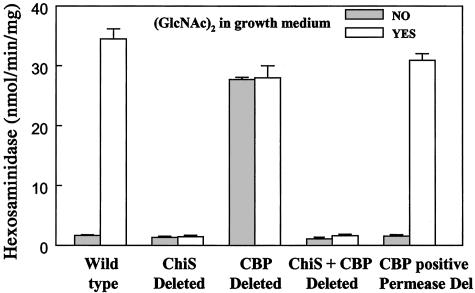

Extracts of cells grown in the presence and absence of 0.6 mM (GlcNAc)2 were therefore assayed as described in Materials and Methods, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. (i) Total hexosaminidase activity is induced ≈17-fold in wild-type cells by (GlcNAc)2. (ii) The sensor deletion neither expresses the chitinolytic genes nor is induced by (GlcNAc)2. These are the expected results from the model in Fig. 1, i.e., ChiS must be activated for derepression of the chitinolytic genes. (iii) According to the model, one way to activate the sensor would be to mutate or delete CBP, and such a mutant should express the chitinolytic genes constitutively, i.e., without requiring induction by (GlcNAc)2. This is precisely the result shown in Fig. 3. (iv) As expected, a double mutant in both the sensor and binding protein genes could not be induced. (v) The (GlcNAc)2 transporter is encoded by VC0616–VC0620; a mutation in any of the genes was unable to transport (GlcNAc)2 or the nonmetabolizable analogue, MeTCB (8). The results in Fig. 3 show that a deletion of the permease, VC0616–VC0619, but not of VC0620, which encodes the periplasmic binding protein, CBP, behaves like the wild-type strain. It is fully inducible. Thus, cell signaling by (GlcNAc)2 does not require that it be transported but only that the periplasmic binding protein CBP be expressed.

Fig. 3.

The expression of total β-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity and its regulation [induction by (GlcNAc)2] requires both the sensor, ChiS, and the periplasmic binding protein, CBP. Preparation of mutants, growth conditions, induction, extraction, and the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase assay technique are described in Materials and Methods. The error bars indicate the range of results obtained with a minimum of three different cell preparations. The permease deletion is a deletion of the four genes required for (GlcNAc)2 transport, VC0619–VC0616, but not of VC0620, the gene encoding CBP. Essentially the same results were obtained when a single gene of the permease group, VC0616, was deleted.

Discussion

Chitin Degradation. Not only is chitin degradation exceedingly complex, but it is stringently regulated. For instance, expression of extracellular chitinase is catabolite repressed (4) in the marine Vibrios described here. Glucose has a similar effect on chitinase secretion by Streptomyces lividans (24). Expression of chitinase and a chitin binding protein by Serratia marcescens 2170 is induced by chitin and by (GlcNAc)2 (25). In this organism, the disaccharide is taken up by the bacterial phosphotransferase system, first identified in E. coli (26–28). S. marcescens mutants defective in (GlcNAc)2 transport are unable to express either the chitinase or the binding protein (25). Finally, two genes in Streptomyces thermoviolaceus, designated chiS and chiR, are located upstream of the chitinase gene, chi40 on the chromosome. The putative regulatory genes, chiS and chiR, have an ≈2-fold effect on the induced level of chitinase activity (29).

Chitin Catabolic Sensor/Kinase, chiS, and the Periplasmic Binding Protein CBP. ChiS has a global effect. It regulates expression of 50 genes, most of which are involved in chitin catabolism.† Furthermore, regulation by ChiS appears to be much tighter than by previously reported systems.

The data presented here on the β-N-acetylglucosaminidases and determined elsewhere on other proteins and processes (unpublished work) all support the model shown in Fig. 1. There is no regulation without CBP. It serves to keep the sensor locked in its “default” state until the environmental signal, (GlcNAc)n, removes CBP, activates the sensor, and derepresses the chitin catabolic genes.

CBP and Other Solute Specific Periplasmic Binding Proteins (PBP). At least 30 PBP have been identified in E. coli (21, 22, 30), most or all of which participate in the transport of their specific ligands. Five PBP bind sugars and three of this group (ribose, galactose, and maltose) also signal the cells to respond via chemotaxis to the sugars as a result of binding of the sugar/PBP complex to a methylating chemoreceptor protein. The maltose/BP complex has been the most extensively studied, especially by Manson and his coworkers (31). The complex binds to the aspartate membrane receptor, Tar, which activates the phosphorylation cascade in the chemotaxis system. Similarly, the Gal/Glc and Rib PBP bind to the Trg chemoreceptor. In an analogous system, Agrobacterium tumefaciens carries a set of virulence (vir) genes on Ti plasmids that cause the growth of crown gall tumors in infected plants. Two regulatory Ti genes encode a two-component His kinase sensor, VirA and VirG, which induce expression of the vir genes in the presence of certain plant phenols and sugars; the sugars act via a chromosomally encoded PBP called ChvE. The sugar/ChvE complex is suggested to bind to a Trg-like site in the periplasmic domain of VirA (32, 33), which transmits the signal to VirG. ChvE mutants do not respond to the sugars but continue to respond to the phenols, although the plant host range becomes more limited.

The periplasmic binding protein reported here, CBP, is unique because unlike all of the examples cited above, it apparently interacts with the sensor ChiS in the absence of the sugar ligand. Additionally, while CBP is induced 20- to 30-fold by (GlcNAc)2, the sensor is maintained in the negative phenotypic mode by the constitutive, low levels of CBP. This result implies that CBP has a high affinity for the periplasmic domain of ChiS.

Is CBP/ChiS the sole system of this type, or is the CBP/ChiS system a paradigm for other binding proteins and sensors? It would be surprising if the mechanism reported here was not a general one because the PBP are ideally constituted for such signaling. They are usually freely exposed to the low-molecularweight putative signaling solutes in the environment, and they have high-affinity binding constants for these solutes. They should also bind with high affinity to the periplasmic domains of the relevant sensors because they must interact at constitutively expressed concentrations, i.e., before induction of the PBP by the signaling molecules.

Bacteria Sense the Presence of Chitin via the Specific Marker (GlcNAc)n. It appears logical that chitinolytic bacteria have developed a system for regulating chitin catabolism based on the presence or absence of the environmental signal (GlcNAc)n, and not, for instance, on the monosaccharide GlcNAc. The rationale is as follows.

The glycosidases that hydrolyze chitin give small quantities of products such as GlcNAc, glucosamine, oligosaccharides of both monosaccharides, and oligosaccharides that contain both glucosamine and GlcNAc. However, the vast majority of bacterial chitinases (as well as many eukaryotic chitinases) yield (GlcNAc)2 as the major end product.

One pathway for the metabolism of (GlcNAc)2 is its further hydrolysis by a host of hexosaminidases to GlcNAc, a sugar that is avidly used by the Vibrios. But GlcNAc is also derived from a wide variety of other sources including a large group of polysaccharides called glycosaminoglycans, and from glycoproteins and glycolipids as well. Thus, GlcNAc would be a poor, nonspecific signal for the cells to start expressing the chitin catabolic machinery. (GlcNAc)n is derived specifically from chitin and is therefore an excellent signal to these bacteria that chitin is in the vicinity.‡

The present results complement a previously suggested idea (4) to answer the following question: How do these bacteria sense and find chitin in the ocean waters? Their ability to do so is astonishing. Our proposal was based on two observations: first, that starving V. furnissii cells secrete large quantities of extracellular chitinase, and second, that (GlcNAc)2 and higher oligosaccharides are exceedingly potent bacterial chemoattractants (20, 34). The inference is that the secreted chitinase from starving cells§ comes into contact with chitin in the microenvironment and generates a disaccharide and/or a (GlcNAc)n gradient, and that the cells swim up this gradient to the cuticle or chitin. We can now extend this idea. (GlcNAc)n induces expression of the chitin catabolic cascade genes under control of ChiS, including the extracellular chitinase, and the cells remain in this state as long as (GlcNAc)n is generated. When the chitin is completely depleted, the periplasmic binding protein again binds to ChiS and “locks” it into the minus configuration, and the system is turned off.

Further evidence must be obtained to establish the validity of the model proposed in this article. For example, attempts will be made to determine whether the purified periplasmic binding protein binds to the cloned periplasmic domain of the sensor, the Kassoc and stoichiometry of the binding, the effect of (GlcNAc)n, etc. Additionally, we do not know the default state of the sensor (kinase or phosphatase), whether it is a monomer or dimer, or the identity of cognate response regulator(s). Further experiments should answer some of these questions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ann Stock (Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway) for valuable suggestions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM51215 and a grant from New England Biolabs kindly made available by Dr. Donald Comb.

Abbreviations: CBP, chitin oligosaccharide binding protein; PNP-GlcNAc, p-nitrophenyl β-d-N-acetylglucosaminide.

Footnotes

By using a DNA microarray assay, 41 genes were shown to be specifically induced and 9 genes were specifically repressed by (GlcNAc)n or crab shells but not by GlcNAc. Most of the 41 induced genes were repressed in the sensor deletion; i.e., they do not respond to (GlcNAc)n. The nine repressed genes include the (GlcNAc)2-specific genes of the phosphoenolpyruvate:glycose phosphotransferase system (PTS) (K. L. Meibom, X.L., A. T. Nielsen, C.-Y. Wu, S.R., and G. K. Schoolnik, unpublished work).

The disaccharide is also found in blood glycoproteins where it links oligosaccharides to the polypeptide chains of the proteins. These oligosaccharides contain a variety of sugars, and their hydrolysis requires many discrete enzymes. Thus, it is unlikely that these substances could yield significant quantities of (GlcNAc)2 in the marine environment. However, in a more limiting environment rich in glycoproteins and hydrolases, such as the intestine, conceivably sufficient (GlcNAc)2 could be generated to result in expression of the chitinolytic genes. In this connection, it may be relevant to note that (GlcNAc)2 also signals V. cholerae to express special pili and other genes, possibly involved in the infective process.

Both starvation and (GlcNAc)n independently signal the cells to secrete extracellular chitinase(s). Whether these are the same or different chitinases remains to be determined.

References

- 1.Stock, A. M., Robinson, V. L. & Goudreau, P. N. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 183–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inouye, M. & Dutta, R. (2003) Histidine Kinases in Signal Transduction (Academic, San Diego).

- 3.Zobell, C. E. & Rittenberg, S. C. (1937) J. Bacteriol. 35, 275–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keyhani, N. O. & Roseman, S. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1473, 108–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouma, C. L. & Roseman, S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33457–33467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chitlaru, E. & Roseman, S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33433–33439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keyhani, N. O., Li, X. & Roseman, S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33068–33076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keyhani, N. O., Wang, L.-X., Lee, Y. C. & Roseman, S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33409–33413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keyhani, N. O. & Roseman, S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33414–33424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keyhani, N. O. & Roseman, S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33425–33432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park, J. K., Keyhani, N. O. & Roseman, S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33077–33083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park, J. K., Wang, L.-X. & Roseman, S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15573–15578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park, J. K., Wang, L.-X., Patel, H. V. & Roseman, S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29555–29560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon, O., Georgellis, D., Lynch, A. S., Boyd, D. & Lin, E. C. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 2960–2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horowitz, S. T., Roseman, S. & Blumenthal, H. J. (1957) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79, 5046–5049. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Seidman, J. G., Smith, J. A. & Struhl, K. (1996) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, eds. Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Seidman, J. G. & Struhl, K. (Wiley, New York), pp. 1–3.

- 17.Kleckner, N., Bender, J. & Gottesman, S. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 204, 139–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Favre, D. & Viret, J.-F. (2000) BioTechniques 28, 199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heidelberg, J. F., Eisen, J. A., Nelson, W. C., Clayton, R. A., Gwinn, M. L., Dodson, R. J., Haft, D. H., Hickey, E. K., Peterson, J. D., Umayam, L., et al. (2000) Nature 406, 477–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassler, B. L., Gibbons, P. J., Yu, C. & Roseman, S. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 24268–24275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furlong, C. E. (1987) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology, eds. Neidhardt, F. C., Ingraham, J. L., Low, K. B., Magasanik, B., Schaechter, M. & Umbarger, H. E. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), 1st Ed., 1st Ed., pp. 768–796.

- 22.Boos, W. & Lucht, J. M. (1996) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology, eds. Neidhardt, F. C., Curtis, R., III, Ingraham, J. L., Lin, E. C. C., Low, K. B., Magasanik, B., Reznikoff, W. S., Riley, M., Schaechter, M. & Umbarger, H. E. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), 2nd Ed., pp. 1175–1209.

- 23.Jannatipour, M., Soto-Gil, R. W., Childers, L. C. & Zyskind, J. W. (1987) J. Bacteriol. 169, 3785–3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito, A., Fujii, T., Yoneyama, T. & Miyashita, K. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 2911–2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchiyama, T., Kaneko, R., Yamaguchi, J., Inoue, A., Yanagida, T., Nikaidou, N., Regue, M. & Watanabe, T. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 1776–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keyhani, N. O. & Roseman, S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 14367–14371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keyhani, N. O., Rodgers, M. E., Demeler, B., Hansen, J. C. & Roseman, S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33110–33115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keyhani, N. O., Wang, L.-X., Lee, Y. C. & Roseman, S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33084–33090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsujibo, H., Hatano, N., Okamoto, T., Endo, H., Miyamoto, K. & Inamori, Y. (1999) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 181, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macnab, R. M. (1987) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology, eds. Neidhardt, F. C., Ingraham, J. L., Low, K. B., Magasanik, B., Schaechter, M. & Umbarger, H. E. (Am. Soc. Microbiol, Washington, DC), 1st Ed., pp. 732–759.

- 31.Zhang, Y., Gardina, P. J., Kuebler, A. S., Kang, H. S., Christopher, J. A. & Manson, M. D. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 939–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cangelosi, G. A., Ankenbauer, R. G. & Nester, E. W. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 6708–6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng, W.-T., Lee, Y.-W. & Nester, E. W. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 5632–5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bassler, B. L., Gibbons, P. J. & Roseman, S. (1989) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 161, 1172–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]