Abstract

There is a growing emphasis on the role of organizations as settings for dissemination and implementation. Only recently has the field begun to consider features of organizations that impact on dissemination and implementation of evidence-based interventions. This manuscript identifies and evaluates available measures for 5 key organizational-level constructs: (1) leadership; (2) vision; (3) managerial relations; (4) climate; and (5) absorptive capacity. Overall the picture was the same across the five constructs—no measure was used in more than one study, many studies did not report the psychometric properties of the measures, some assessments were based on a single response per unit, and the level of the instrument and analysis did not always match. We must seriously consider the development and evaluation of a robust set of measures that will serve as the basis of building the field, allow for comparisons across organizational types and intervention topics, and allow a robust area of dissemination and implementation research to develop.

Introduction

Over the past several years researchers and practitioners alike have recognized the need for more research focused on dissemination and implementation (D & I) of evidence-based programs to promote health and manage chronic disease. Organizations (e.g. schools, workplaces, hospitals) are considered important settings for delivering health promotion interventions (Brownson, Haire-Joshu, & Luke, 2006; Fielding, 1984; Katz, 2009). There is a reasonably robust literature across organizational settings on the delivery of health promotion interventions. However, only recently has the field begun to consider features of organizations that facilitate or inhibit the D & I of evidence-based interventions.

Some of the earlier studies examining the role of organizations in the delivery of evidence-based interventions have considered primarily structural features, such as organization size, complexity, and formalization (Drazin & Schoonhoven, 1996; Emmons & Biener, 1993; Emmons et al., 2000; Emont & Cummings, 1989). Some of these features may in fact reflect less tangible but perhaps more important characteristics of organizations in influencing D & I decisions, such as organizational readiness (Weiner, 2009; Weiner, Amick, & Lee, 2008), leadership, climate(Helfrich, Weiner, McKinney, & Minasian, 2007), and organizational culture(Barnsley, Lemieux-Charles, & McKinney, 1998; Ferlie, Gabbay, Fitzgerald, Locock, & Dopson, 2001; Kanter, 1988; Van de Ven, Polley, Garud, & Venkataraman, 1999). For example, although organizational size has been well-studied, it is likely a proxy for other determinants, such as extent of resources available and functional differentiation or specialization of roles (Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, & Kyriakidou, 2004). Much of the literature at this point is conceptual, with a call for increased research examining the role of these factors in D & I.

A key challenge in the transition from research focused on evidence generation to that focused on D& I is the unit of analysis. The very nature of dissemination efforts often requires an organizational perspective, moving beyond the individual as the unit of analysis and exploring how organizational factors impact on dissemination efforts. Although such an approach is relatively new in the health field, other fields have historically focused on organizations as a key intervention target (e.g. organizational behavior and theory, public policy, education) and have extensively utilized organizational-level measures to assess factors influencing organizational behavior and outcomes.

To build the field of D & I research, we need reliable and valid measures. Recent reviews have reported a dearth of such measures even when considering the broader literature. For example, Weiner recently developed a conceptual framework of organizational readiness to change (Weiner, 2009) and completed an extensive review examining how organizational readiness for change has been defined and measured in health services research and other fields(Weiner, Amick, & Lee, 2008). Analysis of 106 peer-reviewed articles revealed conceptual ambiguities and disagreements, and limited evidence of reliability or validity for most publicly available readiness measures.

As health promotion research increasingly examines organizational-level factors, the need for good operational definitions and measures of key organizational characteristics becomes clearer. The purpose of the proposed manuscript is to identify available measures for key organizational-level constructs that are important for D & I research, to evaluate the measures’ psychometric properties, and to determine if additional measures are needed. A key goal from the outset was to recommend measures that appear to have sound psychometric properties so that a larger body of research using common measures could develop.

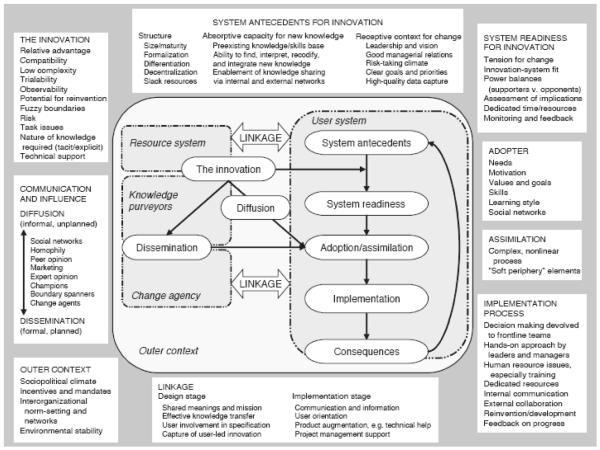

The starting point was to identify and evaluate the extant measures related to organizational factors. To guide this work, we selected Greenhalgh and colleagues’ (Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, & Kyriakidou, 2004) conceptual framework for considering the determinants of D & I within health service and delivery organizations (see Figure 1). This framework identifies three categories of system antecedents for innovation that relate to the organizational-level factors that may influence dissemination outcomes: (1) structure; (2) absorptive capacity for new knowledge; and (3) receptive context for change. Since there has been considerable attention in the literature to structural variables, for this review we focused on absorptive capacity and four features of receptive context (leadership, vision, managerial relations, and climate). We provide a brief review of the literature for each of these 5 constructs below.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model for Considering the Determinants of Diffusion, Dissemination, and Implementation of Innovations in Health Service Delivery and Organization, Based on a Systematic Review of Empirical Research Studies 2004 Wiley. Used with permission from Greenhalgh, Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations, The Milbank Quarterly, Blackwell Publishing.

Leadership

Although leadership has been studied since the 1930s, it is a difficult construct to define and measure. Aditya (Aditya, 2004) argues that leadership centers on both the creation and achievement of goals. The Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness program (GLOBE), a network of researchers that seek to identify effective “universal and culture-specific” leader behaviors and organizational practices, has defined leadership as: “the ability of an individual to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute toward the effectiveness and success of organizations of which they are members”(House et al., 1999).

Leadership is thought to be an important component of organizational change, and may be particularly important in terms of encouraging members of an organization to think in new ways (Van de Ven, Polley, Garud, & Venkataraman, 1999). Leadership style also has important implications for power balances, social relationships within the organization and across systems, and institutional attitude and approach towards risk-taking (Kanter, 1988; Van de Ven, Polley, Garud, & Venkataraman, 1999).

Vision

Although vision is often seen as a leader’s ability to create and communicate clear direction and rationale for the organization (Alexander, Zakocs, Earp, & French, 2006), it can also be conceptualized as a separate construct that cuts across multiple levels within a given organization. Vision has been defined as a guiding theme or over-riding principle that steers the organization, articulating the desired direction and intentions for the future (Reh).

West (West, 1990) defines vision as “an idea of a valued outcome which represents a higher order goal and a motivating force at work” (Anderson & West, 1998). From a theoretical perspective, we would expect that having a clear vision that values innovation sets the stage for adoption and implementation of new health programs. We might also expect that a clear vision would allow members of an organization to adequately assess whether or not an innovation matches with the existing organizational values and goals of the organization, a concept known as compatibility, as described in Roger’s Diffusion of Innovation Theory (Rogers, 1995).

Managerial Relations

A simple definition for good managerial relations is the positive alliances between groups within an organization to promote change (S. Shortell, Morrison, & Friedman, 1990). (Pettigrew, Ferlie, & McKee, 1992). In clinical settings, Shortell, Morrison and Friedman (S. Shortell, Morrison, & Friedman, 1990) emphasized the significance of: (1) looking for common ground, 2) involving selected physicians early on in planning, 3) carefully identifying the needs and interests of key physicians, and 4) working on a daily basis to build a climate of trust, honesty and effective communications. Pettigrew and colleagues (Pettigrew, Ferlie, & McKee, 1992) also proposed that manager-clinician relations are easier when negative stereotypes have been broken down, and that it is important to understand what clinicians value. In fact, managers who were best at promoting change had semi-immersed themselves in the world of clinicians, understood the implications of medical workflow, and perhaps even helped clinicians to do their own planning as a way of earning trust.

Climate

Climate describes organizational members’ perceptions of their work environment. Climate captures the meaning or significance that organizational members perceive in organizational policies, procedures, and practices. These perceptions enable organizational members to interpret current events, predict possible outcomes, and gauge the appropriateness of their own actions and those of others (Jones & James, 1979).

There is some debate as to whether climate is a homologous multi-level construct. Some argue that the construct’s meaning, measurement, and relations with other variables differ across levels of analysis. Reflecting this position, scholars distinguish between psychological climate, a property of individuals that refers to personal perceptions of work environment, and organizational climate, which is a property of the collective and refers to shared perceptions of work environment.

Climate is also a multifaceted construct. In a classic formulation, James and his colleagues identified five primary work environment facets: (1) job characteristics; (2) role characteristics; (3) leadership characteristics; (4) work group and social environment characteristics; and (5) organizational and subsystem attributes (LR James & Sells, 1981; Jones & James, 1979). More recently Patterson and his colleagues (Patterson et al., 2005) identified 17 facets of work environment. Confirmatory factor analysis provides support for both approaches (LA James & James, 1989; Patterson et al., 2005).

Absorptive Capacity

An important albeit quite under-studied construct is absorptive capacity, or an organization’s ability to access and effectively use information. Absorptive capacity was originally conceptualized as an organization’s cognitive structures and prior related knowledge that underline learning (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Zahra & George (Zahra & George, 2002) expanded this definition to include: (1) a broad set of skills needed to deal with and modify transferred knowledge; and (2) the organization’s capacity to learn and solve problems. This construct reflects the process by which ideas from outside of the organization are captured, circulated internally, adapted for the organizational culture/environment, internalized, and integrated into organizational routines. Absorptive capacity reflects an organization’s ability to find and utilize knowledge. In the theoretical literature, there is a discussion of potential vs. realized absorptive capacity, with the former focusing on organizational capability for knowledge acquisition/assimilation, and the latter focused on use of absorbed knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Daghfous, 2004) suggest that an organization’s absorptive capacity depends on that of its individual members, but is not simply a summation of individual capacity. As Caccia-Bava and colleagues (Caccia-Bava, Guimaraes, & Harrington, 2006) point out, organizational absorptive capacity is best understood in terms of the structures that allow multiple organizational members to gather, communicate, apply, and exploit diverse knowledge within the organization.

Methods

In order to identify measures of these five constructs, we searched the peer-reviewed literature using PubMed, CINAHL®, and ISI Web of ScienceSM. With assistance from a reference librarian, we formulated a set of search strings that combined each of the target organizational constructs (organization, climate; managerial relations; leadership; vision; absorptive capacity) and the following terms: innovation, diffusion, adoption, implementation, and health. All search strings included the target construct and “health”, and were applied to the title, abstract, and keyword list. We added wildcard characters to all terms in order to capture potentially important permutations (e.g., innovate, innovating, innovative, and innovation). We restricted the search to English-only articles. Overall, we identified 1178 articles in PubMed, 946 articles in CINAHL, and 1698 articles in ISI Web of ScienceSM . The distribution of these articles by construct is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Articles Identified for Each Construct, by Source

| Construct | PubMed | CINAHL® | ISI Web of Science |

Identified Through Article References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unrestricted

Search |

||||

| Leadership | 549 | 428 | 303 | 0 |

| Vision | 215 | 212 | 234 | 0 |

| Managerial Relations |

21 | 23 | 1001 | 0 |

| Climate | 375 | 235 | 141 | 0 |

| Absorptive capacity |

18 | 48 | 19 | 13 |

|

Restricted

Search |

Non-Duplicative Articles

Retained After Full-Text Review |

|||

| Leadership | 41 | 10 | 35 | 12 |

| Vision | 16 | 22 | 9 | 2 |

| Managerial Relations |

3 | 1 | 58 | 9 |

| Climate | 5 | 7 | 31 | 14 |

| Absorptive capacity |

5 | 15 | 16 | 3 |

Of articles identified, we then reviewed the abstracts using four predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. First, articles had to report original empirical research and appear in a peer-reviewed journal. Second, articles had to mention the organizational construct or a close synonym in the abstract and employ a quantitative measure of the construct. Third, articles had to include a measured outcome relevant to innovation, diffusion, adoption, or implementation. Examples of such outcomes include implementation of an innovation, defined as a new program, product, service, practice, or technology; the spread of an innovation through an organization or social system; the decision to use an innovation; the process of putting an innovation into practice; and the level of initial use of an innovation, or the sustained use of an innovation beyond an initial trial period. Finally, articles had to focus on a health service or health-related intervention or outcome. Research studies involving schools, businesses, or other organizational settings were included if they focused on a health-related intervention, such an employee wellness program or a tobacco cessation program.

We assigned each article retained after full-text review a unique identification number and used a structured data abstraction form to extract key information from each article (e.g., study setting, construct name, construct dimensionality, number of items, and construct level). Table 2 shows the “dictionary” that we used to structure the data abstraction form. We then created tables to display, categorize, and analyze the information we extracted.

Table 2.

Coding Form Used to Abstract Article Information

| Domain | How Coded |

|---|---|

| Author and Year | Author and year |

| Study Setting | Types of organizations included in study

|

| Construct Name | Name of construct used by authors |

| Measure Name | Name of measure or scale used by authors |

| Construct Dimensions | S = Single (one) dimension If multiple, names of construct dimensions |

| Number of Items | Number of items comprising the climate measure |

| Construct Level | I = Assessed at individual level of analysis |

| T = Assessed at team or group level of analysis | |

| O = Assessed at organizational level of analysis | |

| M= Assessed at multiple levels of analysis | |

| Responses per Unit | If construct assessed at team or organizational level of analysis:

|

| Outcome Type | G = Innovation generation |

| A = Innovation adoption | |

| I = Innovation implementation | |

| S = Innovation sustainability/institutionalization | |

| Outcome Variable(s) | Name of outcome variable(s) examined in study |

| Outcome Level | I = Individual-level of analysis |

| O = Organization-level of analysis |

We used Trochim’s (Trochim & Donnelly, 2007) classification of validity and reliability types (see Table 3), in which construct validity is regarded as an umbrella term that includes translational validity and criterion-related validity. Translational validity includes both face and content validity. Criterion-related validity includes predictive, concurrent, convergent, and discriminant validity. Reliability includes inter-rater or inter-observer reliability, parallel forms reliability, test-retest reliability, and inter-item reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha). In this review, we combined face and content validity into a single category. We did the same for the various forms of reliability assessment.

Table 3.

Types of Validity and Reliability Examined in this Review

|

Construct Validity: The degree to which inferences can legitimately be made from an instrument to the theoretical construct that it purportedly measures |

|

Translation Validity: Translation validity is the degree to which an instrument accurately translates (or carries) the meaning of the construct |

|

Face Validity: A summary perception that an instrument’s items to translate or carry the meaning of the construct. Procedures for assessing face validity include informal review by experts or more formal review through a Delphi process. |

|

Content Validity: A check of instrument’s items against the content domain of the construct. Examples include expert review based on a clear definition of the construct and a checklist of characteristics that describe the construct. If the construct is multi- dimensional, factor analysis could be used to verify the existence of those theoretically meaningful dimensions. |

|

Criterion-Related Validity: An empirical check on the performance of an instrument against some criteria |

|

Predictive Validity: The degree to which an instrument predicts a theoretically meaningful outcome. Examples include regression analysis in which the instrument serves as an independent variable. Predictive validity is not demonstrated if the instrument serves as a dependent variable. |

|

Concurrent Validity: The degree to which an instrument distinguishes groups it should theoretically distinguish (e.g., a depression screener distinguishes depressed and non- depressed patients). |

|

Convergent Validity: The degree to which an instrument performs in a similar manner to other instruments that purportedly measure the same construct (e.g., two measures show a strong positive correlation). Convergent validity is most often assessed through confirmatory factor analysis. |

|

Discriminant Validity: The degree to which an instrument performs in a different manner to other instruments that purportedly measure different constructs (e.g., the two measures show a zero or negative correlation). Discriminant validity is most often assessed through confirmatory factor analysis. |

|

Reliability: The consistency or repeatability of an instrument’s measurement. Examples include inter-rater or inter-observer reliability, test-retest reliability, parallel forms reliability, and internal consistency reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha). |

Results

Leadership

Description of articles

Twelve articles examined the association of organizational leadership and health innovation dissemination. Among these, six (50%) focused on health care organizations, three (25%) on public health organizations, and two (16%) on schools; one article (8%) focused on multiple settings. Table 4 shows the diversity of dimensions included in the leadership construct and Table 5 summarizes results for leadership and the other organizational constructs.

Table 4.

Description of Research Studies

| Author /Year |

Study Setting |

Construct Name |

Construct Dimensions |

Number of Items |

Construct Level |

Responses per Unit |

Outcome Type |

Outcome variable(s) |

Outcome Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Leadership * Outcome type: G – Innovation Generation; A – Innovation Adoption; I – Innovation Implementation; S – Innovation Sustainability/Institutionalization | |||||||||

| Bin Saeed, 1995 | Health care |

Leadership commitment |

Single dimension of leadership commitment |

11 | Indiv/Org | Multiple | I | QA implementation | Org |

| Evashwick & Ory , 2003 | Public health |

Leadership | Leader at start, Leader continuing, Champion in addition to leader |

3 | Org | Single | S | Sustainability of innovative community-based health programs |

Org |

| Kegler, 1998 | Public health |

Leadership | Single dimension of leadership |

6 | Indiv, combined for Team |

Multiple | I | Implementation (of action plan) (# of activities implemented) |

Org |

| Livet, 2008 | Public health |

Leadership | Single dimension of leadership |

10 | Org | Multiple | I | Implementing computer programming frameworks |

Org |

| Marchionni, 2008 | Health care |

Transformative leadership (Multifactor leadership questionnaire) |

Idealized influence, Inspirational motivation, Individualized consideration, Intellectual stimulation |

45 | Org | Multiple | I | Extent of guideline implementation |

Org |

| McFadden et al, 2009 | Health care |

Leadership | Single dimension of leadership |

8 | Indiv | Multiple | I | Patient safety initiatives |

Org |

| Roberts-Gray, 2007 | Schools | School based leadership |

Single dimension of school based leadership |

4 | Org | Single | I | Implementation of school program |

Org |

| Roberts-Gray, 2007 | Schools | External leadership |

Single dimension of external leadership |

1 | Org | Single | I | Implementation of school program |

Org |

| Seguin, 2008 | Multiple | Leadership style |

Organization, Support, Communication, Conflict resolution |

8 | Indiv | Single | I | Implementers | Indiv |

| Seguin, 2008 | Multiple | Leadership competence |

Single dimension of leadership competence |

2 | Indiv | Single | I | Implementers | Indiv |

| Somech, 2006 | Health care |

Participative leadership |

Single dimension of participative leadership |

3 | Team | Multiple | I | Team innovation | Team |

| Somech, 2006 | Health care |

Directive leadership |

Single dimension of directive leadership |

6 | Team | Multiple | I | Team innovation | Team |

| Thaker, 2008 | Schools | School leadership & administrative support |

Single dimension of school-based leadership & administrative support |

3 | Team, Org |

NR | A, S | Adoption of program | Org |

| Weiner, 1996 | Health care |

Governance structure |

Physician involvement in governance, Management involvement in governance |

5 | Org | Multiple | A, S | Adoption of CQI | Org |

| Weiner, 1996 | Health care |

Leadership for quality |

CEO involvement in CQI/TQM, Board quality monitoring, Board activity in quality |

3 | Org | Multiple | A, S | Leadership for quality | Org |

| West, 2003 | Health care |

Leadership clarity |

Single dimension of leadership clarity |

11 | Indiv, Team |

Multiple | I | Team innovation | Org |

| Vision | |||||||||

| Inamdar, 2002 | Health care |

Vision | Single dimension of vision |

1 | Org | Multiple | I | Overcome barriers to implementation |

Org |

| Livet, 2008 | Public health |

Shared vision | Single dimension of shared vision |

4 | Org | Single | I | Use of programming processes |

Org |

| Managerial Relations | |||||||||

| Lukas, 2009 | Health | Management support |

Personal leadership support Practical management support |

1=7; 2=8 | Indiv | Multiple | I | Implementation of advanced clinic access |

Indiv/Org |

| Organizational Climate | |||||||||

| Allen et al, 2007 | Multiple | Organizational climate |

Single dimension of climate |

8 | Org | Multiple | I | Provider screening for domestic violence |

Org |

| Anderson & West, 1998 | Health care |

Proximal work group climate |

Vision Participative Safety Task orientation Support for innovation |

38 | Team | Multiple | A | Innovativeness (various measures) |

Team |

| Bostrom et al, 2007 | Health care |

Organizational climate |

Challenge Freedom Support for ideas Trust Liveliness Playfulness/humor Debate Conflicts Risk-taking Idea time |

50 | Indiv | N/A | I | Research utilization in daily clinical practice |

Indiv |

| Brownson et al, 2007 | Public health |

Organizational climate |

Single dimension of climate |

2 | Org | Single | A | Presence of evidence-based physical activity interventions |

Org |

| Choi et al, 2009 | Multiple | Unsupportive climate |

Single dimension of climate |

5 | Indiv | N/A | G | Peer-rated creative performance |

Indiv |

| Gittelson et al, 2003 |

Schools | School climate |

Single dimension of climate |

1 | Org | M | I | Pathways intervention implementation (various measures) |

Org |

| Glisson et al, 2008b |

Mental Health/ Substance Abuse |

Climate | Stress Engagement Functionality |

46 | Org | Multiple | S | Sustained use of new clinical program, service, or treatment model |

Org |

| Gregory et al, 2007 | Schools | School climate |

Negative relationships Administrative leadership Supportive climate |

40 | Org | Multiple | I | Prevention intervention implementation (level and change) |

Org |

| McCormick et al, 1995 | Schools | Organizational climate |

Single dimension of climate |

32 | Org | Unclear | I | Implementation level of use |

Org |

| Nystrom et al , 2002 | Health care |

Organizational climate |

Risk orientation External orientation Achievement orientation |

16 | Org | Multiple | A | Organizational innovativeness |

Org |

| Parcel et al, 2003 | Schools | School climate |

Supportive Directive Restrictive Collegial Intimate Disengaged |

79 | Org | Multiple | S | Institutionalization of CATCH intervention (various process and outcome measures) |

Org |

| Schoenwald et al, 2008 | Mental health/ substance abuse |

Organizational climate |

Fairness Role clarity Role overload Role conflict Cooperation Growth and advancement Job satisfaction Emotional exhaustion Personal accomplishment Depersonalization |

Unclear | Indiv/Org | Multiple | I | Therapist adherence to multi-systemic therapy, client outcomes |

Indiv/Org |

| Simpson et al , 2007 | Mental health/ substance abuse |

Organizational climate |

Clarity of program mission Staff cohesiveness Staff autonomy Communication Stress Openness to change |

30 | Org | Multiple | A | Trial use of therapeutic alliance workshop materials |

Org |

| Wilson et al, 1999 | Health care |

Organizational climate |

N/A | Unclear | Org | Multiple | A | Radicalness and relative advantage of innovations adopted |

Org |

| Absorptive Capacity | |||||||||

| Caccia-Bava, 2006 | Health | Absorptive capacity |

Evaluation & assimilation of knowledge; Ability to apply knowledge internally |

5 | Org | Single | A | Technology adoption | Org |

| Knudsen & Roman, 2004 | Mental health/ substance abuse |

Absorptive capacity |

Environmental scanning; Collection of satisfaction data; Level of workforce professionalism |

10 | Org | Single | A | Substance abuse treatment innovations |

Org |

| Belkhodja, Amara, Landry, Ouimet, 2009 |

Public health |

Absorptive capacity |

Size of the unit If are employees who are paid to do research |

2 | Org | Single | A | Research utilization | Org |

Table 5.

Summary of Findings Across Constructs

| Domain | # Measures Used | # Constructs | # Construct Dimensions |

# Items (range) |

# Measures with reliability and some form of validity measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership | 16 | 9 | 24 | 1-45 | 4 |

| Vision | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1-4 | 0 |

| Managerial Relations |

1 | 1 | 2 | 15 | 0 |

| Organizational Climate |

14 | 3 | 45 | 1-79 | 12 |

| Absorptive Capacity |

3 | 1 | 7 | 2-10 | 0 |

The articles examined various leadership dimensions, including leadership: commitment, clarity, champion, transformational leadership, style, competence, and administrative support, among others. The measures of leadership included one to forty-five items. Several articles measured more than one dimension of leadership; in all, there were 16 leadership measures identified across the 12 studies reviewed.

Five articles (42%) reported measurement of the leadership construct at the organizational level of analysis. One article (8%) measured the construct at the team level of analysis, and two articles (16%) assessed leadership at the individual level of analysis; one article (8%) measured leadership at both the individual level and organizational level of analysis; one article (8%) measured leadership at the team and organizational levels; and two articles (16%) measured the construct at the individual level and then combined responses to create a team level variable. Among the articles that described leadership measured at either the team or organizational level, two used assessments of leadership based on a single response per unit, eight studies based the assessment on multiple respondents per unit, and one article did not report the number of responses per unit used.

Organizational leadership was examined in the context of several dissemination-related outcomes. Nine (75%) focused on innovation implementation, one (8%) focused on innovation sustainability (Evashwick & Ory, 2003), and two (16%) focused on innovation adoption and innovation sustainability (Thaker et al., 2008) (Weiner, Alexander, & Shortell, 1996). In all but three cases (Kegler, Steckler, McLeroy, & Malek, 1998; McFadden, Henagan, & Gowen, 2009)(West et al., 2003), the level of the outcome variable matched the level of the leadership variable. Thaker (Thaker et al., 2008) assessed leadership at the team and organizational level and outcomes on the organizational level, and Bin Saeed (Bin Saeed, 1995) (looked at leadership at the individual and organizational levels and outcomes at the organizational level.

Analysis of Instruments for Measuring Organizational Leadership

There was no agreement across the articles about how leadership should be assessed; our review identified 16 different measures to assess organizational leadership in dissemination-related studies, with no measures used in more than one study.

Psychometric properties of instruments were reported in some of the studies. Four studies (33% of articles, representing five measures) reported face/content validity (Bin Saeed, 1995; McFadden, Henagan, & Gowen, 2009; Roberts-Gray, Gingiss, & Boerm, 2007; Somech, 2006). Five studies (42%) reported reliability (Bin Saeed, 1995; Livet, Courser, & Wandersman, 2008; Marchionni & Ritchie, 2008; McFadden, Henagan, & Gowen, 2009; Somech, 2006). Ten of the leadership constructs measured either reported on or exhibited predictive validity for dissemination related outcomes. For example, Bin Saeed (Bin Saeed, 1995) collected data from 202 physicians across three hospitals in Saudi Arabia to determine factors associated with implementation of a hospital based quality assurance (QA) program. Using factor analysis to identify dimensions related to implementing QA programs, an 11-item scale was created for “leadership commitment.” In a subsequent analysis using multiple regression, this leadership construct was significantly associated with implementation of the QA program. West (West et al., 2003) measured leadership clarity among 3447 respondents from health care teams in the UK. Leadership clarity predicted levels of innovation among community mental health teams and breast cancer care teams, but not among primary health care teams. Table 6 summarizes the psychometric properties assessed in each study.

Table 6.

Assessment of Validity and Reliability for Instruments Identified in Review

| Instrument Name |

Key Citations |

Predictive validity* |

Face/ content validity |

Concurrent validity |

Convergent validity |

Discriminant validity |

Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership | |||||||

| Self Efficacy (Program Specific) | Seguin, 2008 |

|

|||||

| Leadership Style | Seguin, 2008 |

|

|||||

| Bridge-it Capacity Survey | Roberts-Gray, 2007 |

|

|

||||

| Participative Leadership | Somech, 2006 |

|

|

|

|||

| Directive Leadership | Somech, 2006 |

|

|

|

|||

| QA Implementation | Bin Saeed, 1995 |

|

|

||||

| Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire | Marchionni, 2008 |

|

|||||

| Transformational Leadership | McFaddin, 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Leadership Clarity | West, 2003 |

|

|||||

| Partnership Self-Assessment Tool (Weiss et al., 2002) |

Livet, 2008 |

|

|

||||

| Champion | Livet, 2008 |

|

|||||

| Vision | |||||||

| None | |||||||

| Managerial Relations | |||||||

| Personal Leadership Support** Practical Management Support** |

Lukas, 2009 |

No |

|||||

|

Organizational Climate * For dissemination outcomes related to health services or health behavior | |||||||

| Organizational Climate* | Allen et al, 2007 |

|

|

|

|||

| Team Climate Inventory (TCI) | Anderson & West, 1998 |

|

|

|

|

||

| Creative Climate Questionnaire (CCQ) |

Bostrom et al, 2007 |

|

|||||

| Organizational Climate* | Brownson et al, 2007 |

|

|

|

|||

| Unsupportive Climate |

Choi et al, 2009 Scott & Bruce, 1994[S] |

|

|

|

|

||

| School Climate* | Gittelson et al, 2003 |

|

|

||||

| Organizational Social Context (OSC) | Glisson et al, 2008a Glisson et al, 2008b [S] |

|

|

|

|

||

| School Climate Kettering SCS Emotional Triangles |

Gregory et al, 2007 Johnson et al, 1999 [S] Henry et al , 1991 [S] |

|

|

|

|||

| Organizational Climate |

McCormick et al , 1995 Steckler et al, 1992 [S] |

|

|||||

| Organizational Climate* |

Nystrom et al, 2002 Litwin & Stringer, 1967[S] Stern, 1967 [S] Narver & Slater, 1990[S] |

|

|

|

|

||

| School Climate |

Parcel et al, 2003 Hoy et al, 1991[S] |

|

|

||||

| Organizational Climate |

Schoenwald et al, 2008 James & Sells,1988 [S] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| TCU Organizational Readiness for Change* |

Simpson et al, 2007 Lehman et al, 2002[S] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Organizational Climate |

Wilson et al, 1999 Litwin & Stringer,1967 [S] |

|

|

|

|||

| Absorptive Capacity | |||||||

| AC/Managerial IT Knowledge Communication Channels Availability of Technical Specialists (Boundary Spanners) |

Caccia-Bava, 2006 Boynton, 1994 Nilakanta & Scamell, 1990 Chakrabarti, et al., 1983 Daft & Lengel, 1986 Boynton, 1994 Grover, 1993 Ettlie, et al., 1984 Cohen & Levinthal, 1990 |

|

|

||||

| Workforce Professionaliam | Knudsen & Roman, 2004 |

support) |

|

||||

| Environmental Scanning |

|

|

|||||

| Satisfaction |

|

|

|||||

| Unit Size Paid Research Staff |

Belkhodja, Amara, Landry, Ouimet, 2009 |

|

|||||

Vision

Description of articles

Of the two articles examining the association of vision and innovation dissemination, one took place in a health care organization and the other in a public health organization (see Table 4 for study description).

Analysis of Instruments for Measuring Vision

Both studies examined the association of organizational vision with innovation implementation. Livet, et al. (Livet, Courser, & Wandersman, 2008) measured shared vision and Inamdar (Inamdar, Kaplan, & Bower, 2002) measured presence of a well-defined vision as well as the extent to which vision barriers were overcome by program implementation. Shared vision was measured with four items, and was based on a single response per unit. Presence of a well-defined vision was measured with a one item question. Inamdar (Inamdar, Kaplan, & Bower, 2002) also assessed the extent to which barriers were overcome by successful implementation of the innovative strategy and had interviewees rate (from 1-100%) the extent to which the vision barrier (lack of vision related to adoption and implementation) was overcome. Neither study reported psychometric properties of instruments (see Table 6).

The Livet study (Livet, Courser, & Wandersman, 2008), which aimed to identify organizational mechanisms or characteristics that influence implementation of comprehensive programming frameworks, demonstrated that shared vision was correlated with use of program planning, implementation, and maintenance processes. In the Inamdar study (Inamdar, Kaplan, & Bower, 2002) interviewers asked executives of healthcare organizations that were early adopters of an organizational strategy framework (Kaplan & Norton, 1992) whether or not their organization had a well-defined vision. All but one of these organizations reported having a well-defined vision. These same respondents later rated the extent to which the barriers of having “a lack of vision” was overcome (i.e. the strategy is understood by most of the organization); the average rating was 77%.

Managerial Relations

Description of Articles

Only one article examined the association of managerial relations with implementation (Lukas, Mohr, & Meterko, 2009). This article examined management support in the context of the national implementation of an Advanced Clinical Access initiative in 78 VA medical centers, and included the dimension of managerial support. We did not find any articles that studied the association of managerial relations and innovation adoption, implementation, or dissemination (see Table 4 for study description).

Analysis of Instruments for Measuring Managerial Relations

The single article measuring managerial relations (Lukas, Mohr, & Meterko, 2009) examined 2 dimensions of management support: personal leadership support and practical management support. Personal leadership support was measured using 7 items (Cronbach’s alpha = .89) adapted from scales designed to measure effectiveness of work teams (Lemieux-Charles, Murray, & Baker, 2002; S. M. Shortell et al., 2004). Personal leadership support was measured at the individual level. Practical management support, a facility-level variable, was measured using a summary index created from 8 dichotomous items about the presence of specific practical expressions of management support for the Advanced Clinic Access (ACA) initiative at the facility (Cronbach’s alpha not reported). Contrary to their hypotheses, only personal leadership support was significantly associated with greater ACA implementation (see Table 6). Of note, these 2 dimensions just included items on communication (“..talking about the ACA ” at facility “town meeting” events and staff meetings as well as presentations by clinical staff at managerial meetings) and did not encompass the other characteristics of positive alliances described by Shortell et al (Pettigrew, Ferlie, & McKee, 1992; S. Shortell, Morrison, & Friedman, 1990), which include: 1) looking for common ground, 2) involving selected physicians early in planning, 3) identifying the needs and interests of key physicians, 4) daily efforts to build a climate of trust and honesty; 5) breaking down negative stereotypes; and 6) understanding what physicians valued.

Climate

Description of Articles

Of the 14 articles that examined the association of organizational climate and innovation dissemination in health, four (29%) focused on health care organizations, one (7%) focused on public health organizations, four (29%) focused on schools, three (21%) focused on mental health or substance abuse organizations, and two (14%) focused on more than one type of organization (see Table 4). Six articles measured organizational climate as a one-dimensional construct; these measures of climate included from one to thirty-two items. Eight articles measured organizational climate as a multi-dimensional construct; these measures included sixteen to thirty-nine items.

The majority of articles (n=11) assessed organizational climate at the organization-level of analysis. In all but one case (Brownson et al., 2007), team-level or organization-level assessments of climate were based on the perceptions of multiple respondents per unit. The articles also examined the association of organizational climate with a variety of dissemination-related outcomes, although the majority focused on adoption (5 articles (36%); e.g., presence of innovative medical imaging technologies), and implementation (6 articles (43%); e.g., therapist adherence to multi-systemic therapy). Two articles (14%) focused on sustained innovation use (e.g., institutionalization of obesity prevention interventions in schools). In all but one case, the level of the outcome variable matched the level of the climate variable. Only Schoenwald and colleagues (Schoenwald, Carter, Chapman, & Sheidow, 2008) examined the possibility of cross-level effects—that is, the effects of organizational climate on aggregate (i.e., organization-level) and individual-level therapist adherence to multi-systemic therapy.

Analysis of Instruments for Measuring Organizational Climate

Of the 14 articles reviewed, there were 14 instruments used to assess organizational climate. In other words, each article used a different instrument.

Nine (64%) of the studies reviewed used in whole or in part well-researched, standardized instruments to assess organizational climate. Examples include the Team Climate Inventory, Creative Climate Questionnaire (CCQ), the Organizational Social Context instrument, the Charles F. Kettering School Climate Scale, the TCU Organizational Readiness for Change instrument, and the Organizational Climate Questionnaire (OCQ). Not surprisingly, the psychometric properties of these instruments are better understood than those of locally adapted, exploratory instruments. Even for these well-researched instruments, however, questions remain about their validity and reliability. Mathisen and Einarsen (Mathisen & Einarsen, 2004) raised questions about the translational validity of the CCQ. Although the instrument’s developer defined climate as an organizational attribute, the CCQ measured individual perceptions of the work environment. These authors also note that instrument’s developer has not presented sufficient information to support his claim that the CCQ has adequate psychometric properties. Similarly, several authors have raised doubts—based on empirical study—about the factor structure of the OCQ (Hellriegel & Slocum, 1974; Patterson et al., 2005; Simms & Lafollette, 1975). It remains unclear whether these scales developed by Litwin and Stringer (Litwin & Stringer, 1968) and subsequently used in two of the studies included in this review (Nystrom, Ramamurthy, & Wilson, 2002; Wilson & Ramamurthy, 1999), actually measure what they purport to measure. Likewise, the climate scales in the TCU instrument have displayed variable levels of reliability across types of respondents and settings. For example (Lehman, Greener, & Simpson, 2002), computed alpha coefficients for each of the six climate scales for administrators, staff, and programs. Six of the eighteen alpha coefficients were below the accepted .70 threshold. Other studies also report variable levels of reliability for climate scales, with some also reporting alpha coefficients well below .70 (Rampazzo, De Angeli, Serpelloni, Simpson, & Flynn, 2006; Saldana, Chapman, Henggeler, & Rowland, 2007).

The climate instruments included in this review exhibited mixed results in terms of predictive validity (see Table 6). Three (21%) instruments showed statistically significant associations with dissemination-related outcomes in health. Allen and colleagues (Allen, Lehrner, Mattison, Miles, & Russell, 2007) observed a positive, significant relationship between organizational climate—which they measured as perceived organizational support—and the frequency with which health care providers screened patients for possible domestic violence. In an organizational sample that included medical research and services firms, Choi and colleagues (Choi, Andersen, & Veillette, 2009) found that an unsupportive organizational climate inhibited employee creativity. Finally, Wilson and Ramamurthy (Wilson & Ramamurthy, 1999) observed in correlation analysis that organizations with more risk-oriented climates tended to adopt more radical innovations and innovations that provide greater relative advantage.

Eight (57%) instruments exhibited only partial evidence of predictive validity for dissemination-related outcomes in health. In most cases, some of the dimensions of organizational climate assessed by the instrument were significantly associated with some of the dissemination-related outcomes examined in the study. For example, Anderson and West (Anderson & West, 1998) found that one dimension of team climate, support for innovation, emerged as the only significant predictor of overall innovation and innovation novelty. Another dimension of team climate, participative safety, emerged as the best predictor of the number of innovations. It also emerged as the best predictor of team self-reports of innovativeness. A third dimension of team climate, task orientation, predicted innovations’ anticipated administrative efficiency. Finally, as Table 6 shows, well-researched climate instruments exhibit no greater predictive validity than locally developed, exploratory ones, at least with regard to dissemination-related outcomes in health. It is difficult to interpret the mixed results observed in these and other studies included in this review because the statistically significant relationships between climate dimensions and dissemination-related outcomes displayed no obvious pattern.

Absorptive Capacity

Description of Articles

Of the 3 articles that examined the association of absorptive capacity and dissemination in health, one focused on health care organizations, one focused on private substance abuse organizations, and one focused on governmental health ministries and hospitals (see Table 4).

Analysis of Instruments for Measuring Absorptive Capacity

There was no agreement across the three studies reviewed in terms of how Absorptive Capacity (AC) was measured. Caccia-Bava (Caccia-Bava, Guimaraes, & Harrington, 2006) defined and measured two dimensions of AC: managerial knowledge and communication. The communication dimension encompassed communication channels, cross-function teams for knowledge integration, and communication boundary spanners. Both dimensions were related to hospitals’ IT adoption, the dependent variable. This study also examined the relationship between absorptive capacity and organizational culture; strong developmental and rational cultures and weaker hierarchical culture were significantly related to both dimensions of absorptive capacity (see Table 6).

Knudsen and Roman (Knudsen & Roman, 2004) defined and assessed AC across three different dimensions, including workforce professionalism, environmental scanning, and satisfaction among client referral sources and third party payers. The dependent variable was organizational adoption of treatment innovations. They found partial support for workforce professionalism as a predictor of innovation adoption; both environmental scanning and satisfaction were associated with innovation adoption.

Belkhodja and colleagues (Belkhodja, Amanr, Landry, & Ouimet, 2007) defined absorptive capacity as the size of the unit, as an estimate of its capacity to acquire/absorb knowledge; and whether there were people in the unit who were paid to do research. The dependent variable was whether or not governmental health service organizations used research, assessed for seven types of activities: (1) received research results for areas of responsibility; (2) understood research results; (3) referenced research evidence; (4) adapted research results to provide information to decision makers; (5) promoted adoption of research evidence; (6) made professional decisions based on evidence; and (7) made concrete changes in services provided based on use of research evidence. Absorptive capacity was associated with research utilization. However, the individual components of absorptive capacity had different relationships with research utilization in different kinds of health organizations. Being a medium size unit was related with research utilization in health ministries and hospitals, but not in regional health authorities; being a smaller unit was associated with higher research utilization in regional authorities, as did having paid research staff.

Discussion

There is currently a growing emphasis on the D & I of evidence-based strategies at the organizational level. The standard methodologies used in the health promotion and disease prevention literature to create evidence (e.g. randomized trials) have serious limitations for research focused on how to disseminate evidence-based interventions (Mercer, DeVinney, Fine, Green, & Dougherty, 2007). Attention to measurement issues is critical if we are to make progress in both understanding the factors that influence dissemination and for developing approaches to accelerate the adoption and use of evidence based strategies in practice and community settings (Bowen et al., 2009; Weiner, 2009). The development of this area of research will benefit from use of good measures with adequate psychometric properties.

The purpose of this paper was to identify available measures for 5 key systems antecedents hypothesized to be important for D & I research (Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, & Kyriakidou, 2004), to report on the measures’ psychometric properties, and to develop a compendium of measures that could be recommended for use. We limited our review to peer-reviewed empirical research that focused on outcomes related to innovation, diffusion, adoption, or implementation, that assessed the construct at the organizational level, and that employed a quantitative measure of the construct. Some of the constructs we studied have a larger quantitative literature (e.g. climate, leadership) than others (e.g. managerial relations, absorptive capacity), and thus we expected that we might be able to make more recommendations for measures for those constructs. Overall, however, the picture was the same across the five constructs—no measure of a specific construct was used in more than one study, many studies did not report the psychometric properties of the measures, some assessments were based on a single response per unit, and the level of the instrument did not always match the level of analysis. Thus, we are unable to make any recommendations for specific instruments in any of the five constructs evaluated.

A key issue with the majority of the constructs measured is that they might not be homologous multi-level constructs. That is, the construct’s meaning, measurement, and relationships with other variables differ across levels of analysis. Construct validity issues arise when an organizational characteristic is measured at the individual-level of analysis when such measures do not convey the construct’s emphasis on shared perceptions of the organization. Construct validity issues also arise when data regarding organizational characteristics are obtained from only one individual. One cannot ascertain from a single respondent the extent to which other organizational members share his or her perceptions across the organization. As more research is done using these constructs, it would significantly benefit the field if extant measures were evaluated and built upon, rather than new measures being created for each inquiry. Across all of the constructs, there is a significant need for strong psychometric evaluations of the measures’ properties, and in particular a focus on predictive validity across a range of D & I outcomes. Of particular concern is the considerable diversity in how the constructs are measured, which suggests a lack of theoretical agreement on the constructs’ meaning. This highlights the need for more theoretical work, particularly for construct that do not seem homologous. The need for more careful attention to measurement practices was also apparent in this review. When theory suggests that consensus is important, then it is critical to have more than one respondent. In addition, when multiple respondents are utilized, it is important to conduct the appropriate statistical tests (e.g., within-group agreement statistics) before aggregating to higher levels of analysis.

Three limitations merit discussion. First, our review only covered those articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Our review could be subject to a publication bias if the “gray literature” contains reliable, valid measures of system antecedents for dissemination and implementation that do not also appear in peer-reviewed articles. Second, our review only included articles that contained the term “health” in the title, abstract, or keyword list. Restricting the search in this way facilitated the review by eliminating articles that did not focus on health-related dissemination and implementation issues, our principal concern. However, our search might have missed articles that included disease-specific terms like diabetes, cancer, stroke, or HIV rather than the broader term “health.” Finally, our review only includes articles that contained a measured outcome relevant to innovation, diffusion, adoption, or implementation. Although we accepted a broad range of outcomes within these domains, we excluded articles that measured outcomes in terms of organizational members’ knowledge, attitudes, or behavioral intentions. Researchers interested in reliable, valid measures of system antecedents relevant to these important precursors to dissemination and implementation should exercise care in interpreting and using the results of our review.

It is likely that the concerns raised in this review of measures of systems antecedents of D & I are relevant to other organizational constructs, as was noted in Weiner’s evaluation of measures of organizational readiness (Weiner, Amick, & Lee, 2008). It is important for health promotion researchers to recognize that there is a large literature in other fields focusing on organizational assessment beyond the health sector. Inclusion of this literature was beyond the scope of this review, but may include measures that would be useful in the health context. If we are to build a literature that addresses how to effectively disseminate and implement evidence-based health interventions, we must consider the development and evaluation of a robust set of measures that will serve as the basis of building the field, allowing for comparisons across organizational types and intervention topics, and will allow a robust area of research to develop.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute through the Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network, a network within the CDC’s Prevention Research Centers Program (U48 – DP001911, -U48-DP000057, U48-DP001946, U48/DP000059 , U48/DP001944) and by grants from the National Cancer Institute (1K05 CA124415-01A1, R01 CA124402, R01 CA124397, R01 CA123228). The authors would like to acknowledge Glenna Dawson for her work on the literature reviews, and Nancy Klockson for participation in the manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- Aditya R. Leadership in JC Thomas, Editor Vol 4 Industrial and Organizational Assessment. Wiley and Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander MP, Zakocs RC, Earp JA, French E. Community coalition project directors: what makes them effective leaders? J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(2):201–209. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200603000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen N, Lehrner A, Mattison E, Miles T, Russell A. Promoting systems change in the health care response to domestic violence. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35(1):1-3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson N, West M. Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and validation of the team climate inventory. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1998;19(3):235–258. [Google Scholar]

- Barnsley J, Lemieux-Charles L, McKinney MM. Integrating learning into integrated delivery systems. Health Care Manage Rev. 1998;23(1):18–28. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199801000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkhodja O, Amanr N, Landry R, Ouimet M. The Extent and Organizational Determinants of Research Utilization in Canadian Health Services Organizations. Science Communication. 2007;28(3):377–417. [Google Scholar]

- Bin Saeed K. Implementation of quality assurance program in Saudi-Arabian hospitals. Saudi Medical Journal. 1995;16(2):139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom AM, Wallin L, Nordstrom G. Evidence-based practice and determinants of research use in elderly care in Sweden. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(4):665–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Sorensen G, Weiner BJ, Campbell M, Emmons K, Melvin C. Dissemination research in cancer control: where are we and where should we go? Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(4):473–485. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9308-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton A, Zmud R, Jacobs G. The influence of IT management practice on IT use in large organizations. MIS Quarterly. 1994;18(2):83–8. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Ballew P, Dieffenderfer B, Haire-Joshu D, Heath GW, Kreuter MW, et al. Evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity: what contributes to dissemination by state health departments. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(1 Suppl):S66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.011. quiz S74-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Luke DA. Shaping the context of health: a review of environmental and policy approaches in the prevention of chronic diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:341–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccia-Bava M, Guimaraes T, Harrington S. Hospital organization culture, capacity to innovate and success in technology adoption. Journal of Health Organization and Management. 2006;20(3):194–217. doi: 10.1108/14777260610662735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti A, Feineman S, Fuentevilla W. Characteristics of sources, channels, and contents for scientific and technical information systems in industiral R and D. IEEE Trans Engineering Management, EM. 1983;30(2):83–8. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Andersen T, Veillette A. Contextual Inhibitors of Employee Creativity in Organizations The Insulating Role of Creative Ability. Group & Organization Management. 2009;34(3):330–357. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen W, Levinthal D. Absorptive capacity: new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1990;35:128–152. [Google Scholar]

- Daft R, Lengel RH. Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Mangagement Scienc. 1986;32(5):554–71. [Google Scholar]

- Daghfous A. Absorptive Capacity and the Implementation of Knowledge-Intensive Best Practices. SAM Advanced Management Journal. 2004;69(2):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Drazin R, Schoonhoven C. Community, population, and organziation effects on innovation: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Journal. 1996;39(5):1065–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons KM, Biener L. The Impact of organizational characteristics on hospital smoking policies. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1993;8(1):43–49. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-8.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons KM, Thompson B, McLerran D, Sorensen G, Linnan L, Basen-Enquist K, et al. The relationship between organizational characteristics and the adoption of workplace smoking policies. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(4):483–501. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emont SL, Cummings KM. Adoption of smoking policies by automobile dealerships. Public Health Rep. 1989;104(5):509–514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettlie J, Bridges W, O’Keefe R. Organization stragegy and structural differences for radical versus incremental innovation. Management Science. 1084;30(6):682–95. [Google Scholar]

- Evashwick C, Ory M. Organizational characteristics of successful innovative health care programs sustained over time. Fam Community Health. 2003;26(3):177–193. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie E, Gabbay J, Fitzgerald L, Locock L, Dopson S. Evidence-based medicine and organisational change: an overview of some recent qualitative research. Palgrave; Bastingstoke: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding JE. Health promotion and disease prevention at the worksite. Annual Review of Public Health. 1984;5:237–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.05.050184.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittelsohn J, Merkle S, Story M, et al. School climate and implementation of the Pathways study. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 2):S97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S, et al. Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: implications for research and practice. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(1-2):98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A, Henry DB, Schoeny ME. School climate and implementation of a preventive intervention. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;40(3-4):250–60. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9142-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover V. An empirically dreived model for the adoption of customer-based interorganizational systems. Decision Sciences. 1993;24(3):603–40. [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich CD, Weiner BJ, McKinney MM, Minasian L. Determinants of implementation effectiveness: adapting a framework for complex innovations. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(3):279–303. doi: 10.1177/1077558707299887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellriegel D, Slocum JJ. Organizational Climate: Measures, Research and Contingencies. The Academy of Management Journal. 1974;17(2):255–280. [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, Chertok F, Keys C, Jegerski J. Organizational and family systems factors in stress among ministers. Am J Community Psychol. 1991;19(6):931–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00937892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House R, Hanges P, Ruiz-Quintanilla S, Dorfman P, Javidan M, Dickson M, et al. Cultural influences on leadership and organizations: Project GLOBE. In: Mobley W, Gessner M, Arnold V, editors. Advances in global leadership. JAI Press; Stamford, CT: 1999. pp. 171–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy W, Tarter C, Kottkamp R. Open schools/health schools: measuring organizational climate. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Inamdar N, Kaplan RS, Bower M. Applying the balanced scorecard in healthcare provider organizations. J Healthc Manag. 2002;47(3):179–195. discussion 195-176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James L, James L. Integrating Work Environment Perceptions: Explorations into the Measurement of Meaning. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1989;74:739–751. [Google Scholar]

- James L, Sells S. Psychological climate: theoretical perspectives and empirical research. In: Magnussen D, editor. The situaion: an intercational perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. pp. 201–250. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Johnson A, Kranch D, Zimmerman K. The development of a university version of the Charles F. Kettering Climate Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1999;59(2):336–350. [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, James L. Psychological climate: Dimensions and relationships of individual and aggregated work environment perceptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 1979;23(2):201–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter R. When a thousand flowers bloom: structural, collective and social conditions for innovation in organisation. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RS, Norton DP. The balanced scorecard--measures that drive performance. Harv Bus Rev. 1992;70(1):71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DL. School-based interventions for health promotion and weight control: not just waiting on the world to change. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler MC, Steckler A, McLeroy K, Malek SH. Factors that contribute to effective community health promotion coalitions: a study of 10 Project ASSIST coalitions in North Carolina. American Stop Smoking Intervention Study for Cancer Prevention. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(3):338–353. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Roman PM. Modeling the use of innovations in private treatment organizations: the role of absorptive capacity. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26(1):353–361. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WE, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assessing organizational readiness for change. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(4):197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux-Charles L, Murray M, Baker G. THe effects of quality improvement practies on team effectiveness: a mediational model. J Organ Behav. 2002;23(5):533. [Google Scholar]

- Litwin G, Stringer R. Motivation and organization climate. Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University; Boston: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Livet M, Courser M, Wandersman A. The prevention delivery system: organizational context and use of comprehensive programming frameworks. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):361–378. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas CV, Mohr DC, Meterko M. Team effectiveness and organizational context in the implementation of a clinical innovation. Qual Manag Health Care. 2009;18(1):25–39. doi: 10.1097/01.QMH.0000344591.56133.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchionni C, Ritchie J. Organizational factors that support the implementation of a nursing best practice guideline. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(3):266–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen G, Einarsen S. A review of instruments assessing creative and innovative environments within organizations. Creativity Research Journal. 2004;16(1):119–140. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden K, Henagan S, Gowen CI. The patient safety chain: Transformational leadership’s effect on patient safety culture, initiatives, and outcomes. Journal of Operations Management. 2009;27(5):390–404. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick LK, Steckler AB, McLeroy KR. Diffusion of innovations in schools: a study of adoption and implementation of school-based tobacco prevention curricula. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9(3):210–9. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer SL, DeVinney BJ, Fine LJ, Green LW, Dougherty D. Study designs for effectiveness and translation research :identifying trade-offs. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2):139–154. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystrom P, Ramamurthy K, Wilson A. Organizational context, climate and innovativeness: adoption of imaging technology. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management. 2002;19(3-4):221–247. [Google Scholar]

- Parcel GS, Perry CL, Kelder SH, et al. School climate and the institutionalization of the CATCH program. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(4):489–502. doi: 10.1177/1090198103253650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson M, West M, Shackleton V, Dawson J, Lawthorn R, Maitlis S, et al. Validating the organizational climate measure: links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2005;26(4):379–408. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew F, Ferlie E, McKee L. Shaping Strategic Change: Making Change in Large Organizations: The Case of the National Health Service. Sage Publications; London: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rampazzo L, De Angeli M, Serpelloni G, Simpson DD, Flynn PM. Italian survey of organizational functioning and readiness for change: a cross-cultural transfer of treatment assessment strategies. Eur Addict Res. 2006;12(4):176–181. doi: 10.1159/000094419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reh F. [Accessed September 7, 2010];Vision. In http://management.about.com/cs/generalmanagement/g/Vision.htm. (Vol. September 7, 2010)

- Roberts-Gray C, Gingiss PM, Boerm M. Evaluating school capacity to implement new programs. Eval Program Plann. 2007;30(3):247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. The Free Press; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana L, Chapman JE, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD. The Organizational Readiness for Change scale in adolescent programs: Criterion validity. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Carter RE, Chapman JE, Sheidow AJ. Therapist adherence and organizational effects on change in youth behavior problems one year after multisystemic therapy. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(5):379–394. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0181-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S, Bruce R. Determinants of Innovative Behavior - a Path Model of Individual Innovation in the Workplace. Academy of Management Journal. 1994;37(3):580–607. (1990) [Google Scholar]

- Seguin RA, Palombo R, Economos CD, Hyatt R, Kuder J, Nelson ME. Factors related to leader implementation of a nationally disseminated community-based exercise program: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:62. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortell S, Morrison E, Friedman B. Strategic Choices for America’s Hospitals. Jossey Bass; San Francisco: [Google Scholar]

- Shortell SM, Marsteller JA, Lin M, Pearson ML, Wu SY, Mendel P, et al. The role of perceived team effectiveness in improving chronic illness care. Med Care. 2004;42(11):1040–1048. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortell S, Morrison E, Friedman B. Strategic Choices for America’s Hospitals. Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Simms H, Lafollette W. Assessment of Litwin and Stringer Organization Climate Questionnaire. Personal Psychology. 1975;28(1):19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal GA. Linking the elements of change: Program and client responses to innovation. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(2):201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somech A. The Effects of Leadership Style and Team Process on Performance and Innovation in Functionally Heterogeneous Teams. Journal of Management. 2006;32(1):132–157. [Google Scholar]

- Steckler A, Goodman RM, McLeroy KR, Davis S, Koch G. Measuring the diffusion of innovative health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1992;6(3):214–224. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaker S, Steckler A, Sanchez V, Khatapoush S, Rose J, Hallfors DD. Program characteristics and organizational factors affecting the implementation of a school-based indicated prevention program. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(2):238–248. doi: 10.1093/her/cym025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trochim W, Donnelly J. Research methods knowledge base. Thomson Custom Pub; Mason, OH: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven A, Polley D, Garud R, Venkataraman S. The Innovation Journey. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci. 2009;4:67. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ, Alexander JA, Shortell SM. Leadership for quality improvement in health care; empirical evidence on hospital boards, managers, and physicians. Med Care Res Rev. 1996;53(4):397–416. doi: 10.1177/107755879605300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ, Amick H, Lee SY. Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: a review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(4):379–436. doi: 10.1177/1077558708317802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss ES, Anderson RM, Lasker RD. Making the most of collaboration: exploring the relationship between partnership synergy and partnership functioning. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(6):683–98. doi: 10.1177/109019802237938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West M. Innovation and Creativity at Work: Psychological and Organizational Strategies. Wiley; Chinchester: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- West M, Borrill C, Dawson J, Brodbeck F, Shapiro D, Haward B. Leadership clarity and team innovation in health care. The Leadership Quarterly. 2003;14(4-5):393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Ramamurthy K. A multi-attribute measure for innovation adoption: the context of imaging technology. Engineering Management, IEEE Transactions. 1999;46(3):311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra A, George G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization and extension. Academy of Management Review. 2002;27(2):185–203. [Google Scholar]