Abstract

Background

Identification of new genes that are mutated in osteosarcomas is critical to developing a better understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of this disease and discovering new targets for therapeutic development.

Methods

We identified somatic non-synonymous coding mutations in oncogenes associated with human cancers and hotspot mutations from tumor suppressor genes that were either well-described in literature or seen multiple times in human cancer sequencing efforts. We then systematically characterized 961 mutations in 89 genes across 98 osteosarcoma tumor samples and cell lines. All identified mutations were replicated on an independent platform using homogeneous mass extend MALDI-TOF (Sequenom hME Genotyping).

Results

We identified 14 mutations in at least one osteosarcoma tumor sample or cell line. Some of the genetic changes identified were in tumor suppressor genes previously known to be altered in osteosarcoma: p53 (R273H, R273C, and Y163C) and RB1 (E137*). Notably, we identified multiple mutations in PIK3CA (H1047R, E545K, and H701P) which have never previously been observed in osteosarcoma. Additionally, we observed mutations in KRAS (G12S), CUBN (I3189V, seen in two separate tumor samples), CDH1 (A617T, seen in two separate tumor samples), CTNNB1 (N287S), and FSCB (S775L).

Conclusion

We performed the largest mutational profiling of osteosarcoma to date and identified for the first time several mutations involving the PI3 kinase pathway – adding osteosarcoma on to the growing list of malignancies with PI3 kinase mutations. Additionally, we initiated a mutational map detailing DNA sequence changes across a variety of osteosarcoma subtypes and offered new candidates for therapeutic targeting.

Keywords: Genotyping, Osteosarcoma, OncoMap, PIK3CA, Mutation

Introduction

Osteosarcomas are aggressive primary bone malignancies that have a peak incidence in adolescence – accounting for 60% of primary bone cancers diagnosed in patients < 20 years old1-5. Patients with localized osteosarcoma develop metastatic disease in greater than 80% of cases when not treated with chemotherapy, and these patients usually die from their cancer if found to progress during or after treatment with standard chemotherapy regimens6-8. For patients with progressive or recurrent disease despite treatment using standard agents including cisplatinum, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and methotrexate, therapeutic strategies other than cytotoxic drugs are needed9-12.

Understanding the genetic mutations that drive cancer pathogenesis have recently led to identification of new treatments for several cancers such as EGFR-mutated lung cancers13, 14, cKit mutated gastrointestinal stromal tumors15, 16, and ALK-translocated tumors17, 18. As a result, recent research efforts on osteosarcoma have focused on identifying new treatment targets and prognostic markers12, 19-21. Of the molecular targets currently under evaluation for osteosarcoma, IGF1R22-25, EGFR26-29, STAT330, 31, PLK132-34, and mTOR35-37, among others, are being intensely evaluated. To date, however, none of these targets have yet been proven to be of therapeutic benefit to patients with advanced osteosarcoma22.

A whole genome sequencing approach in lung, breast, and colon cancer samples has identified numerous genetic alterations38, 39, but many of these mutations are incidental and unlikely to play an important role in tumor pathogenesis or as therapeutic targets. Currently, a whole genome sequencing approach for osteosarcomas would be prohibitively expensive and results would be difficult to interpret. Therefore, taking advantage of insights gained in treatment of other tumor types, we sought to focus our analysis only on mutations that have a higher a priori chance at playing an important role in osteosarcoma pathogenesis (see Methods for Selection of Cancer Gene Mutations), and we genotyped for mutations known to occur in oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes that have been previously associated in literature with cancer pathogenesis.

Methods

Osteosarcoma tumor samples

Fresh frozen tumor specimens were obtained from the clinical archives of Dr. Francis Hornicek (Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital) and the Massachusetts General Hospital Tissue Repository. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained to study all samples from the Partners Human Research Office (2007P-002464).

Cell Culture

The human osteosarcoma cell line KHOS was kindly provided by Dr. Efstathios Gonos (Institute of Biological Research & Biotechnology, Athens, Greece), and U-2OS and SaOS were purchased from the ATCC (Rockville, MD). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen,) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100-units/ml penicillin and 100μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2-95% air atmosphere and passaged when near confluent monolayers were achieved using trypsin-EDTA solution. Cells were free of mycoplasma contamination as tested by MycoAlert(R) Mycoplasma Detection Kit from Cambrex (Rockland, ME).

Extraction of Genomic DNA

Extraction of DNA from osteosarcoma tumor tissues and cell lines were performed using QIAamp® DNA Micro kit (Qiagen). The extraction was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, osteosarcoma tumor tissue sample or cell pellet from cultured cell lines of ∼8 mg in weight was transferred to a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube and 180 ul of buffer ATL was added immediately. After equilibrating to room temperature (25C), 20 ul of proteinase K was added and mixed by vortexing for 15 seconds. The sample tube was incubated at 56°C overnight until the sample was completely lysed. In the next day, 200 ul buffer AL was added and mixed by vortexing for 15 seconds. Subsequently, 200 μl of ethanol (96-100%) was added. The mixture obtained was loaded on a QIAamp MiniElute spin column provided by the kit and washed with AW1 followed by AW2 buffers. DNA was eluted with 60 μl of buffer AE and preserved at −20 °C until use.

Selection of Cancer Gene Mutations and OncoMap Assay Design

Selection of cancer gene mutations for assay design and mass spectrometric genotyping were performed as previously described in Thomas et al. with modifications indicated in MacConaill et al.40, 41.

In brief, we queried the Sanger Institute COSMIC database, PubMed, and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) databases for known somatic oncogene and tumor suppressor gene mutations. Non-synonymous coding mutations that have been previously reported to occur as somatic mutations in human cancers were selected and rank ordered based on (1) the frequency of mutation in cancers, (2) frequency across cancer subtypes, and (3) the feasibility of developing an inhibitor of the target gene. Most genes that were described in only one instance were excluded unless that gene was determined to be very important in tumorigenesis and/or the gene was currently in drug development pipelines of pharmaceutical companies. “Hotspot” mutations from selected well-known tumor suppressor genes were included based on the number of documented occurrences, with higher weight given to genes commonly deleted or genetically inactivated across cancer types.

For each mutation, the discriminating nucleotides for both wild-type and mutant alleles were determined, enabling insertions or deletions to be represented by single base changes. Subsequently, 250 bases of neighboring DNA were added to each side of the resulting mutation assay to enable primer design. These primers for PCR amplification and the extension probe were designed using the Sequenom MassARRAY Assay Design 3.0 software, applying default single base extension (SBE) settings and default parameters but with the following modifications: maximum multiplex level input adjusted to 24; maximum pass iteration base adjusted to 100. For complex mutations, genotyping assays were designed manually. The resulting 501 base pair DNA sequences were queried in the dbSNP database to avoid incorporation of SNPs during assay design. Resulting primer were then run through BLAT and modified where necessary to avoid pseudogene amplification. The resulting list of primer pairs and extension probes (OncoMap version 2.0) consists of 961 assays interrogating 89 oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes for mutations (single-base substitutions, insertions and deletions). All PCR primers and extension probes were synthesized unmodified using standard purification (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA).

Mass Spectrometric Genotyping

Mass spectrometric genotyping was performed as previously described40-42. In brief, primers and probes were pooled, and all assays were validated on the CEPH panel of human HapMap DNAs (Coriell Institute) as well as a panel of human cell lines with known mutational status. Genomic DNA from all tumor samples was quantified using Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) and subjected to whole-genome amplification (WGA), with the following modifications: 100ng of genomic DNA was used as input for WGA and a post-WGA cleanup step was implemented using a Nucleofast Purification Kit (Macherey-Nagel).

The Qiagen Repli-g kit was used for phi29-mediated WGA of fresh frozen and cell line DNA. After quantification and dilution of genome-amplified DNA, mass spectrometric genotyping using iPLEX chemistries was performed as previously published 41.

After iPLEX genotyping (32 iPLEX pools with an average pool plex size of 14.4 assays), samples harboring candidate mutations were further filtered by manual review. Samples harboring candidate mutations were selected for experimental confirmation using multi-base extension homogenous Mass-Extend (hME) chemistry with plexing of ≤6 assays per pool. Conditions for hME validation were consistent with the methods described by MacConaill et al. 2009. Primers and probes used for hME validation were designed using the Sequenom MassARRAY Assay Design 3.0 software, applying default multi-base extension (MBE) parameters but with the following modifications: maximum multiplex level input equal to 6; maximum pass iteration base adjusted to 200.

Western Blotting for PI3 kinase pathway proteins

The human AKT, pAKT(Thr308), and p4EBP1(Thr37/46) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Dedham, MA). The mouse monoclonal antibody to human actin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Western blot analysis was performed as described previously43. Briefly, the cells were lysed in 1× radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Upstate Biotechnology) and protein concentration was determined by the DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). Total protein (25 μg) was resolved on NuPage 4% to 12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and immunoblotted with specific antibodies. Primary antibodies were incubated in TBS (pH 7.4) with 0.1% Tween 20 with gentle agitation overnight at 4°C. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad) were incubated in TBS (pH 7.4) with 5% nonfat milk (Bio-Rad) and 0.1% Tween 20 at a 1:2,000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. Positive immunoreactions were detected by using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology).

Results

Characteristics of Clinical Tumor Samples

A total of 98 DNA samples were derived from cell lines or patients who had undergone operative resection of their osteosarcoma (Table 1). In summary, 68 specimens were obtained from fresh frozen tissue, 26 were derived from FFPE blocks, and 4 were derived from cell lines that were created from primary tumor samples. 83 samples had detailed pathologic subclassification information available, and the majority of samples were either of osteoblastic (21) or conventional (25) subtypes. The average known age of patients at time of surgery was forty years old (as this study only collected from patients age 20 or older). Because the available clinical dataset was incomplete, no available clinical characteristic or outcome correlated with the mutational status of the tumor.

Table 1. Patient and Tumor Characteristics.

| Subject # | Gender | age | date of tumor collection | histologic subtype | grade (1-3 of 3) | Location | Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | f | 21 | 1993 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | right femur and acetabulum | |

| 2 | f | 21 | 1993 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | right femur | |

| 3 | f | 24 | 1996 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | left tibia | |

| 4 | f | 24 | 1996 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | left tibia | |

| 5 | f | 25 | 1997 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 3 | left tibia | |

| 6 | f | 25 | 1994 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | left distal femur | |

| 7 | f | 30 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 8 | f | 31 | 1996 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 | femur | PIK3CA H701P |

| 9 | f | 32 | 2000 | CHONDROSARCOMA | 2 | left acetabulum | |

| 10 | f | 32 | 1995 | MIXED OSTEOBLASTIC AND CHONDROBLASTIC | 3 | left pelvis | |

| 11 | f | 32 | 1993 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | left tibia | |

| 12 | f | 32 | 1993 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | left tibia | |

| 13 | f | 33 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 14 | f | 33 | 2001 | TELANGIECTATIC | 3 | right distal femur | |

| 15 | f | 34 | 1996 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 3 | left tibia | |

| 16 | f | 34 | 1996 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 3 | left tibia | |

| 17 | f | 34 | 1999 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 - 3 | left femur | |

| 18 | f | 36 | 1996 | MALIGNANT FIBROUS HISTIOCYTOMA | 3 | left knee | |

| 19 | f | 42 | 1993 | CHONDROBLASTIC | 2 | left iliac wing | |

| 20 | f | 44 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 21 | f | 47 | 1993 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 | left distal femur | |

| 22 | f | 47 | 1998 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | right femur | CDH1 A617T FSCB S775L |

| 23 | f | 47 | 1998 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | right femur | |

| 24 | f | 47 | 2000 | OSTEOBLASTOMA | NA | left distal tibia | |

| 25 | f | 48 | 1993 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | left femur | |

| 26 | f | 51 | 1999 | MIXED OSTEOBLASTIC AND FIBROBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | L 5 vertebrae | |

| 27 | f | 54 | 2003 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 | left popliteal region | |

| 28 | f | 55 | 1994 | EPITHELIOID | 3 | right proximal humerus | |

| 29 | f | 56 | 1994 | EPITHELIOID | 3 | right humerus | |

| 30 | f | 66 | 1975 | CHONDROBLASTIC | NA | right tibia | |

| 31 | f | 66 | 1975 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 3 | right proximal tibia | |

| 32 | f | 73 | 1987 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 | left lower leg | |

| 33 | f | 77 | 2001 | MIXED OSTEOBLASTIC AND FIBROBLASTIC | 1 | right prlvis | |

| 34 | f | 92 | 2005 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 - 3 | right femur | |

| 35 | m | 20 | 2001 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 3 | right thigh | |

| 36 | m | 20 | 2004 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2-3 | left distal femur | |

| 37 | m | 23 | 1999 | CHONDROBLASTIC | 2 | left femur | |

| 38 | m | 24 | 2003 | CHONDROBLASTIC | 2 | left tibia | |

| 39 | m | 24 | 2003 | CHONDROBLASTIC | 2 | left proximal tibia | |

| 40 | m | 25 | 2000 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 | right femur | |

| 41 | m | 25 | 1996 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | left humerus | |

| 42 | m | 27 | 1994 | MIXED OSTEOBLASTIC AND CHONDROBLASTIC | 3 | right proximal humerus | |

| 43 | m | 27 | 1996 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | right proximal humerus | |

| 44 | m | 27 | 1996 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | right humerus | |

| 45 | m | 29 | 1995 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 - 3 | right tibia | |

| 46 | m | 29 | 2004 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | left chest wall | |

| 47 | m | 29 | 2004 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | left chest wall | |

| 48 | m | 30 | 1993 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 3 | left proximal humerus | |

| 49 | m | 30 | 1992 | TELANGIECTATIC | 2 | left knee | |

| 50 | m | 30 | 1992 | TELANGIECTATIC | 2 | left knee | |

| 51 | m | 31 | 1996 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 | right femur | |

| 52 | m | 31 | 1991 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 3 | proximal tibia | |

| 53 | m | 32 | 1995 | JUXTACORTICAL | 1 | right femur | |

| 54 | m | 37 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 55 | m | 40 | 1990 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 | left proximal femur | |

| 56 | m | 40 | 1987 | OSTEOSARCOMA WITH CHONDROID FEATURES | 2 | left distal femur | TP53 R273H |

| 57 | m | 40 | 1987 | OSTEOSARCOMA WITH CHONDROID FEATURES | 2 | left femur | |

| 58 | m | 40 | 1987 | OSTEOSARCOMA WITH CHONDROID FEATURES | 1 | left femur | |

| 59 | m | 41 | 2004 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 3 | left leg | |

| 60 | m | 41 | 1997 | SMALL CELL | 2 | right gluteal | |

| 61 | m | 41 | 1997 | SMALL CELL | 2 | right gluteal | |

| 62 | m | 42 | 1994 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 3 | left illiac wing | |

| 63 | m | 42 | 1994 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 3 | pelvis | |

| 64 | m | 43 | 1994 | SMALL CELL | 2 | sacrum | |

| 65 | m | 44 | 2000 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 1 | right scapula | CUBN I3189V |

| 66 | m | 44 | 2000 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 1 | right scapula | |

| 67 | m | 45 | 2002 | CHONDROBLASTIC | 2 | left tibia | |

| 68 | m | 45 | 1997 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 1 | left femur | |

| 69 | m | 45 | NA | OSTEOCHONDROMA | NA | right distal femur | |

| 70 | m | 46 | 1993 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 | right humerus | |

| 71 | m | 47 | 1994 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 - 3 | left superior pubic ramus | |

| 72 | m | 48 | 1991 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 - 3 | left femur | |

| 73 | m | 49 | NA | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | NA | right leg | |

| 74 | m | 51 | 1993 | CHONDROBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | right tibia | |

| 75 | m | 52 | 1993 | CHONDROBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | proximal right tibia | |

| 76 | m | 57 | 1994 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 | left ischium | |

| 77 | m | 60 | 1993 | OSTEOBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | right distal femur | |

| 78 | m | 61 | 1993 | JUXTACORTICAL | 2 | left mid-humerus | |

| 79 | m | 73 | 2005 | CONVENTIONAL OSTEOSARCOMA | 2 | right femur | |

| 80 | m | 73 | 1996 | GIANT CELL OSTEOSARCOMA | NA | right femur | |

| 81 | m | 79 | 2005 | CHONDROBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | paravertebral mass | |

| 82 | m | 79 | 2005 | CHONDROBLASTIC | 2 - 3 | paravetebrae,T10 | |

| 83 | m | 80 | 2001 | SPINDLE CELL SARCOMA | 2 | right femur | |

OncoMap Results

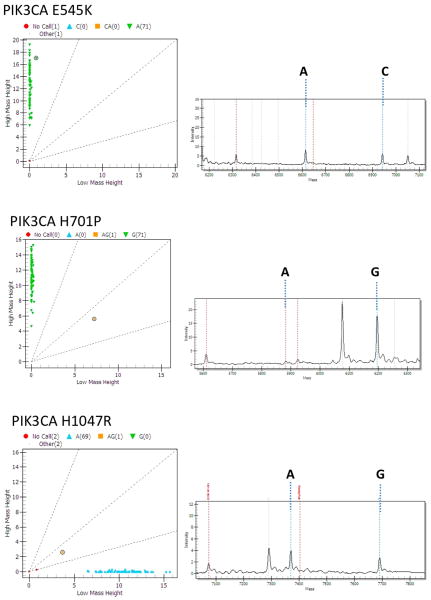

98 osteosarcoma samples were tested for mutations across the 89 genes tested in the Oncomap version 2.0 panel (see Table 2 for list of genes tested). 89/98 samples passed our quality control check, and 96% of assays tested yielded results (see example of readout in Figure 1). 40/98 samples were identified to have at least one mutation. 14 mutations occurring in 8 of the genes tested were identified; these were all validated using an alternate chemistry (hME genotyping) on unamplified DNA.

Table 2. List of Genes Tested.

| ABL1 | EGFR | KRAS | PTEN |

| ABL1 | EPHA1 | LRP1B | PTPN11 |

| ABL2 | EPHA3 | MADH4 | RAF1 |

| ADAMTSL3 | EPHB1 | MAP2K4 | RB1 |

| AKT1 | EPHB6 | MET | RET |

| AKT2 | ERBB2 | MINK1 | ROBO1 |

| AKT3 | ERBB2 | MLL3 | ROBO2 |

| ALK | ERBB4 | MOS | ROS1 |

| AML1/RUNX1 | FBXW7 | MPL | SMAD2 |

| APC | FES | MSH2 | SMAD4 |

| AR | FGFR1 | MSH6 | SMARCB1 |

| AXL | FGFR2 | MST1R | SMO |

| BMX | FGFR3 | MYH1 | SPTAN1 |

| BRAF | FGFR3 | NF1 | SRC |

| BRCA1 | FLJ13479 | NOTCH1 | STK11 |

| BRCA2 | FLNB | NPM | SUFU |

| BUB1B | FLT3 | NPM1 | TBX22 |

| C-MYC | FMS | NRAS | TEC |

| C14orf155 | GATA1 | NTRK1 | TFDP1 |

| CDH1 | GNAS | NTRK2 | TIAM1 |

| CDK4 | GUCY1A2 | NTRK3 | TIF1 |

| CDKN2A | HRAS | PDGFRA | TP53 |

| CEBPA | IGF1R | PDGFRB | TRIM33 |

| CTNNB1 | JAK2 | PDPK1 | TSC1 |

| CUBN | JAK3 | PIK3CA | VHL |

| DBL | KDR | PKHD1 | |

| DBN1 | KIT | PRKCB1 |

Fig 1.

Mass spectrometric cluster plots (left side) and spectral plots (right side) for the PIK3CA mutations identified in this study. The mutation interrogated is indicated above each plot. The sample with the mutation is indicated by a circle in the left panel. The corresponding spectral plot is indicated on the right. The mass of the alleles specific for the indicated assay are shown by dashed lines.

Among the 68 freshly frozen samples tested, 9 mutations were identified and validated. Among the 22 FFPE samples tested, 4 mutations were identified and validated. Among the 4 cell lines tested, 1 mutation was identified and validated. There was no significant difference in discovered mutation rates between freshly frozen and FFPE samples.

The 14 mutations that were identified involved 8 different genes. Some of these genes were previously associated with osteosarcoma pathogenesis: p53 (R273H, R273C, and Y163C) and RB1 (E137*). However, we also identified 3 mutations in PIK3CA (H1047R, E545K, and H701P) which have never previously been observed in osteosarcomas. Other mutations were identified in KRAS (G12S), CUBN (I3189V, seen in two separate tumor samples), CDH1 (A617T, seen in two separate tumor samples), CTNNB1 (N287S), and in FSCB (fibrous sheath CABYR binding protein) (S775L).

Although the study was designed with hopes of correlating mutation with clinical data, only 5 of the samples with identified mutations were annotated with detailed clinical information, a sample size too small to make statistically significant inferences. One patient with grade 2-3 osteoblastic osteosarcoma of the right femur had a mutation in FSCB (S775L) as well as in CDH1 (A617T). Another patient with grade 2 osteoblastic osteosarcoma of the femur had a mutation in PIK3CA (H701P). A patient with osteosarcoma with chondroid features, grade 2 of 3, had a P53 mutation (R273C). A patient with a low grade osteosarcoma of the right scapula had a mutation in CUBN (I3189V).

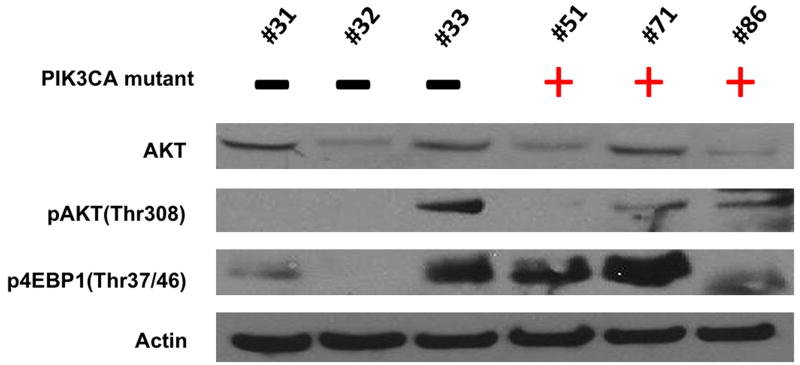

PI3 Kinase Pathway is activated in PIK3CA-mutated osteosarcoma tumor samples

PIK3CA is the gene coding for p110a, which is one of four catalytic units for class I PI3 kinase44, 45. Because the samples that revealed mutations in PIK3CA were from preserved tumor samples rather than cell lines, we were unable to perform functional assays for PI3 kinase activity. Therefore, we used western blot analysis to determine the relative levels of expression for members of the PI3 kinase pathway (Figure 2) when compared to three osteosarcoma tumor samples for which PI3 kinase mutations were not observed. PI3 kinase is known to activate both the AKT and mTOR pathway, so we looked for phospho-AKT as evidence of AKT activity and phospho-4EBP1 as evidence of mTOR activity. We found that all six samples expressed AKT. Two of the three samples with PIK3CA mutations revealed detectable phospho-AKT and all three samples revealed detectable phospho-4EBP1. Unexpectedly, one of the samples without an identified PIK3CA mutation also appeared to have high levels of phospho-AKT and phospho-4EBP1, suggesting an alternate mechanism for hyperactivation of PI3 kinase. Future studies including complete gene sequencing of PI3 kinase pathway members and gene copy number analysis may reveal the mechanism for PI3 kinase activation in this sample.

Fig 2.

Western Blot Analysis of AKT/mTOR Pathway Activation in Osteosarcoma Tissues, 3 without PIK3CA mutations and 3 with PIK3CA mutations.

Discussion

Osteosarcomas have been well-described to have numerous chromosomal aberrations and are characterized by complex karyotypes27, 46, 47. Although high-level amplifications and homozygous deletions have been well described in this tumor type, with one study showing 28.6% and 3.8% of the osteosarcoma genome consisting of amplifications and homozygous deletions 46, a comprehensive genome-wide survey for high-yield mutations have not yet been performed across a large collection of osteosarcomas. Because whole-genome tumor sequencing of large collections of osteosarcomas are costly and prohibitively laborious, we aimed our screen to test only for those mutations that have been previously described in other tumors and implicated in tumor pathogenesis. Of course, results of our study are not equivalent to what can be found by complete sequencing efforts that are currently being undertaken by large consortiums.

It is important to note that in the majority of our samples, we did not identify any mutations. This observation has two critical implications. First, a comprehensive gene sequencing study would likely identify more mutations. For example, although our screen was able to detect a few samples with mutations in p53 and RB, osteosarcomas have been well described to have frequent mutations in both p5348 and RB49. Undoubtedly, complete gene sequencing of p53 and RB in the one hundred osteosarcoma samples tested in this study will yield many more samples with p53/RB mutations. Second, our mutation panel was quite thorough in its examinations of the more clinically relevant mutations found in lung and colon cancer, including mutations in the EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, and PDGFR. Therefore, the lack of identification of any mutations suggest that, for those genes, point mutations are unlikely to be involved in the pathogenesis of osteosarcoma.

We wanted to identify new mutations that could potentially serve as therapeutic targets for the treatment of osteosarcoma. Mutations newly identified in osteosarcoma need not be new to oncology. For example, mutations in cKIT were well-described to predict for the efficacy of the cKIT inhibitor, imatinib, in treating patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors before a rare cKIT mutation in a melanoma led to a trial of treatment with imatinib and a major response50. Likewise, we are hopeful that other drug-mutation relationships that may be established in other cancer subtypes will point to effective drug targets for osteosarcoma.

We were interested in the finding that the validated mutation discovery rate in FFPE samples was similar to that in freshly frozen samples. Until recently, a major limitation to high-throughput multiplexed genotyping assays was the limitation in access to freshly frozen tissue. However, our study as well as other similar studies suggests that FFPE samples are sufficient for mutation discovery.

Although PIK3CA mutations have been described in myxoid/round cell liposarcomas51, such mutations have never been previously described in osteosarcomas. PIK3CA is the gene coding for p110a, the catalytic subunit of class I PI3 kinase. These lipid kinases catalyze the conversion of phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate. These lipid products in turn recruit AKT to the plasma membrane, where it is phosphorylated and itself catalyzes the phosphorylation and activation of other proteins, such as mTOR and 4EBP, that regulate glucose metabolism, cell proliferation, and survival45. In this study, we are the first to observe human osteosarcoma tumor samples harboring mutations in PIK3CA.

When these samples with PIK3CA mutations were analyzed for phosphorylation (and therefore activation) of proteins that signal downstream of PI3 kinase, we confirmed that all three samples expressed phosphorylated 4EBP-1 and that 2 of 3 samples expressed phosphorylated AKT. However, we were surprised to find one sample without an identified PIK3CA mutation also demonstrated high levels of phosphorylated 4EBP-1 and AKT. This observation can be due to either the hyperactivation of other pathways that also activates 4EBP-1 or AKT – such as the RAS/RAF/MAPK, the IGF-1R/IRS-1, and the mTOR pathways, or the loss of PTEN inhibition of AKT activation, or the existence of another PI3 kinase activating mutation that was not tested in this study - highlighting the limitation of this study as a genotyping study of particular mutations and underscoring the ultimate need for whole gene sequencing to comprehensively evaluate the mutation rate of PIK3CA in this cohort.

Further studies need to be done to establish PI3 kinase as a useful signal transduction pathway to target in osteosarcomas. There are at least nine PI3 kinase inhibitors in clinical development44 and, at the time of submission of this manuscript, there are eleven clinical trials using PI3 kinase inhibitors in cancer cohorts posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. The fact that activating mutations in PIK3CA have now been observed in osteosarcomas makes this disease group an interesting cohort to focus on for further pharmaceutical development of PI3 kinase inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by the Jennifer Hunter Yates Foundation, the Kenneth Stanton Osteosarcoma Research Fund, the Cassandra Moseley Berry Sarcoma Endowed Fund, the Gategno and Wechsler Funds, and the KL2 Medical Research Investigator Training (MeRIT) grant awarded to EC via Harvard Catalyst ∣ The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH grant #1KL2RR025757-01 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers).

Footnotes

Authors' disclosures: EC has received financial and research support from Amgen, Sanofi-Aventis, Novartis, and Pharmacyclics. LG is a consultant for Novartis and Foundation Medicine and an equity holder in Foundation Medicine.

References

- 1.Ferguson WS, Goorin AM. Current treatment of osteosarcoma. Cancer Invest. 2001;19(3):292–315. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100102557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geller DS, Gorlick R. Osteosarcoma: a review of diagnosis, management, and treatment strategies. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010 Oct;8(10):705–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorlick R. Osteosarcoma: clinical practice and the expanding role of biology. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2002 Dec;2(6):549–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyers PA, Gorlick R. Osteosarcoma. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997 Aug;44(4):973–989. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mankin HJ. Pathophysiology of orthopaedic diseases. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chi SN, Conklin LS, Qin J, et al. The patterns of relapse in osteosarcoma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004 Jan;42(1):46–51. doi: 10.1002/pbc.10420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis AM, Bell RS, Goodwin PJ. Prognostic factors in osteosarcoma: a critical review. J Clin Oncol. 1994 Feb;12(2):423–431. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goorin AM, Frei E, 3rd, Abelson HT. Adjuvant chemotherapy for osteosarcoma: a decade of experience. Surg Clin North Am. 1981 Dec;61(6):1379–1389. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)42592-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou AJ, Gorlick R. Chemotherapy resistance in osteosarcoma: current challenges and future directions. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006 Jul;6(7):1075–1085. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.7.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo W, Healey JH, Meyers PA, et al. Mechanisms of methotrexate resistance in osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1999 Mar;5(3):621–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mankin HJ, Hornicek FJ, Rosenberg AE, Harmon DC, Gebhardt MC. Survival data for 648 patients with osteosarcoma treated at one institution. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Dec;(429):286–291. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000145991.65770.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Day K, Gorlick R. Novel therapeutic agents for osteosarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009 Apr;9(4):511–523. doi: 10.1586/era.09.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004 May 20;350(21):2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004 Jun 4;304(5676):1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002 Aug 15;347(7):472–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joensuu H, Roberts PJ, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in a patient with a metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. N Engl J Med. 2001 Apr 5;344(14):1052–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butrynski JE, D'Adamo DR, Hornick JL, et al. Crizotinib in ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 28;363(18):1727–1733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 28;363(18):1693–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou AJ, Geller DS, Gorlick R. Therapy for osteosarcoma: where do we go from here? Paediatr Drugs. 2008;10(5):315–327. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200810050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorlick R. Current concepts on the molecular biology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:467–478. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marina N, Gebhardt M, Teot L, Gorlick R. Biology and therapeutic advances for pediatric osteosarcoma. Oncologist. 2004;9(4):422–441. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-4-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chugh R. Experimental therapies and clinical trials in bone sarcoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010 Jun;8(6):715–725. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan Z, Choy E, Harmon D, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor cyclolignan picropodophyllin inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in multidrug resistant osteosarcoma cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009 Aug;8(8):2122–2130. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolb EA, Kamara D, Zhang W, et al. R1507, a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting IGF-1R, is effective alone and in combination with rapamycin in inhibiting growth of osteosarcoma xenografts. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010 Jul 15;55(1):67–75. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulaner GA, Vu TH, Li T, et al. Loss of imprinting of IGF2 and H19 in osteosarcoma is accompanied by reciprocal methylation changes of a CTCF-binding site. Hum Mol Genet. 2003 Mar 1;12(5):535–549. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Do SI, Jung WW, Kim HS, Park YK. The expression of epidermal growth factor receptor and its downstream signaling molecules in osteosarcoma. Int J Oncol. 2009 Mar;34(3):797–803. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman SS, Allen SW, Ganti R, et al. Copy number gains in EGFR and copy number losses in PTEN are common events in osteosarcoma tumors. Cancer. 2008 Sep 15;113(6):1453–1461. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kersting C, Gebert C, Agelopoulos K, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression in high-grade osteosarcomas is associated with a good clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 May 15;13(10):2998–3005. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen YH, Koeppen H, Garcia R, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor in osteosarcoma: expression and mutational analysis. Hum Pathol. 2007 Aug;38(8):1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryu K, Choy E, Yang C, et al. Activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) pathway in osteosarcoma cells and overexpression of phosphorylated-Stat3 correlates with poor prognosis. J Orthop Res. 2010 Jul;28(7):971–978. doi: 10.1002/jor.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryu K, Susa M, Choy E, et al. Oleanane triterpenoid CDDO-Me induces apoptosis in multidrug resistant osteosarcoma cells through inhibition of Stat3 pathway. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duan Z, Ji D, Weinstein EJ, et al. Lentiviral shRNA screen of human kinases identifies PLK1 as a potential therapeutic target for osteosarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2010 Jul 28;293(2):220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi U, Honda K, Satow R, et al. Functional genome screen for therapeutic targets of osteosarcoma. Cancer Sci. 2009 Dec;100(12):2268–2274. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seong YS, Kamijo K, Lee JS, et al. A spindle checkpoint arrest and a cytokinesis failure by the dominant-negative polo-box domain of Plk1 in U-2 OS cells. J Biol Chem. 2002 Aug 30;277(35):32282–32293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gazitt Y, Kolaparthi V, Moncada K, Thomas C, Freeman J. Targeted therapy of human osteosarcoma with 17AAG or rapamycin: characterization of induced apoptosis and inhibition of mTOR and Akt/MAPK/Wnt pathways. Int J Oncol. 2009 Feb;34(2):551–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paoloni MC, Mazcko C, Fox E, et al. Rapamycin pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic relationships in osteosarcoma: a comparative oncology study in dogs. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Q, Deng Z, Zhu Y, Long H, Zhang S, Zhao J. mTOR/p70S6K signal transduction pathway contributes to osteosarcoma progression and patients' prognosis. Med Oncol. 2010 Dec;27(4):1239–1245. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9365-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weir BA, Woo MS, Getz G, et al. Characterizing the cancer genome in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2007 Dec 6;450(7171):893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature06358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006 Oct 13;314(5797):268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas RK, Baker AC, Debiasi RM, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2007 Mar;39(3):347–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacConaill LE, Campbell CD, Kehoe SM, et al. Profiling critical cancer gene mutations in clinical tumor samples. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macconaill LE, Garraway LA. Clinical implications of the cancer genome. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Dec 10;28(35):5219–5228. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan Z, Weinstein EJ, Ji D, et al. Lentiviral short hairpin RNA screen of genes associated with multidrug resistance identifies PRP-4 as a new regulator of chemoresistance in human ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008 Aug;7(8):2377–2385. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cleary JM, Shapiro GI. Development of phosphoinositide-3 kinase pathway inhibitors for advanced cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010 Mar;12(2):87–94. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paez J, Sellers WR. PI3K/PTEN/AKT pathway. A critical mediator of oncogenic signaling. Cancer Treat Res. 2003;115:145–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Man TK, Lu XY, Jaeweon K, et al. Genome-wide array comparative genomic hybridization analysis reveals distinct amplifications in osteosarcoma. BMC Cancer. 2004 Aug 7;4:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lau CC, Harris CP, Lu XY, et al. Frequent amplification and rearrangement of chromosomal bands 6p12-p21 and 17p11.2 in osteosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004 Jan;39(1):11–21. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ito M, Barys L, O'Reilly T, et al. Comprehensive mapping of p53 pathway alterations reveals an apparent role for both SNP309 and MDM2 amplification in sarcomagenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Feb 1;17(3):416–426. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feugeas O, Guriec N, Babin-Boilletot A, et al. Loss of heterozygosity of the RB gene is a poor prognostic factor in patients with osteosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996 Feb;14(2):467–472. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.2.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hodi FS, Friedlander P, Corless CL, et al. Major response to imatinib mesylate in KIT-mutated melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Apr 20;26(12):2046–2051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barretina J, Taylor BS, Banerji S, et al. Subtype-specific genomic alterations define new targets for soft-tissue sarcoma therapy. Nat Genet. 2010 Aug;42(8):715–721. doi: 10.1038/ng.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]