Abstract

Purpose

To elucidate the association between macular pigment optical density (MPOD) and various types of obesity in the South-Indian population.

Patients and methods

In total, 300 eyes of 161 healthy volunteers of South-Indian origin were studied. MPOD was measured psychophysically at 0.25°, 0.50°, 1.00°, and 1.75° eccentricities from fovea. Anthropometric measurements included waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) and body mass index (BMI). Using the WHO Expert Consultation guidelines, obesity was defined based on BMI alone (BMI≥23 kg/m2), based on WC alone (WC≥90 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women), and based on WHR alone (≥0.90 for men and ≥0.85 for women). Isolated generalized obesity was defined as increased BMI and normal WC. Isolated abdominal obesity was defined as increased WC and normal BMI. Combined obesity was defined as increased BMI and increased WC.

Results

Mean MPOD at all eccentricities was not significantly different between men and women. Mean MPOD values did not significantly differ in various types of obesity, when compared with the normal subjects. On subgroup analysis, in age group ≥60 years, mean MPOD values were significantly higher in subjects with obesity based on BMI (0.61 vs0.41, P=0.036), obesity based on WHR (0.67 vs0.41, P=0.007), and isolated generalized obesity (0.66 vs0.41, P=0.045) in comparison with normal subjects at 0.25° eccentricity.

Conclusion

We found lack of an association between MPOD and obesity in the South-Indian population. A similar finding was also noted on age group- and gender-wise analyses.

Keywords: macular pigment optical density, obesity, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, body mass index

Introduction

A reduction in macular carotenoid pigments (MPs) is known to be associated with greater risk for both age-related macular degeneration (AMD)1 and cataract.2, 3 Among all the tissues that store carotenoid pigments,4, 5, 6 adipose tissue is of special relevance, as it contains more than 80% of the body carotenoids.7 Furthermore, obesity is an independent risk factor for the progression of AMD.8 Population-based studies have found an association between AMD and body mass index (BMI).9, 10, 11, 12, 13

Hence, an association has been proposed between macular pigment optical density (MPOD) and obesity; the latter being a reliable measure of chemical concentrations of MP (lutein and zeaxanthin).14 Previous studies have shown a controversial relationship between MPOD and obesity. Although few studies did not find any relationship,15 others showed an inverse association.16, 17, 18

BMI is used as an indicator of ‘generalized' obesity and waist circumference (WC) or waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) as a measure of ‘abdominal' obesity in epidemiological surveys.19 South Asians have greater predisposition to abdominal obesity and visceral fat,20, 21 which is attributed to the so-called ‘Asian Indian phenotype' characterized by increased WC despite lower BMI.22 In Asian Indians, the prevalence of combined obesity was reported to be high among both the sexes; isolated generalized obesity was more common in men and isolated abdominal obesity was more common in women.19 WC was also reported as a better marker of obesity-related metabolic risk than BMI in women compared with men in this population.19 The aim of the present study was to elucidate the association between MPOD and various obesity indices in the South-Indian population.

Materials and methods

Normative data were collected from 300 eyes of 161 healthy volunteers of South-Indian origin from April 2008 to March 2009. From 322 eyes of 161 subjects, 22 eyes with history of cataract surgery were excluded for further analysis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and a written informed consent was obtained from the subjects as per the Helsinki Declaration. Demographic history such as age, gender, and education, and anthropometric measurements such as height, weight, waist and hip were collected. The sample was divided equally among the following age groups of 20–30, 30–40, 40–50, 50–60 and ≥60 years; with each group containing 30 men and 30 women. Subjects included in the study had corrected visual acuity of 20/20. Those with any ocular pathology, history of ocular surgery, systemic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, family history of AMD, past/present smoking history, regular intake of carotenoids/vitamins/antioxidants were excluded. After comprehensive ocular examination, MPOD was calculated as a measure of lutein and zeaxanthin in the retina,14 using Macular Densitometer (Macular Metrics Corp., Rehoboth, MA, USA). All the subjects were naive in psychophysical tasks.

Measurement of MPOD

Macular densitometer is based on the principle of heterochromatic flicker photometry. The basic measurement procedure involves presenting a small test stimulus that alternates between a measuring wavelength (460 nm), which is absorbed by macular pigments, and a reference wavelength not absorbed by the pigments (540 nm). This stimulus is presented in the fovea and in the parafovea. To the subject, this alternating stimulus appears as a small flickering light. The subject is given control of the intensity of the measuring light, and the subject's task is to adjust it to minimize the flicker. Flicker could be eliminated (null zone) if the luminance of the 460-nm light was increased to match that of the 540-nm light. This increase in luminance was related to the optical density of the macular pigment (ie, if there was a larger amount of pigment present, the absorption of the 460-nm light would be greater and its luminance would need to be increased more to match that of the 540-nm light). The amount of 460-nm light required to produce this null zone provides a measure of the MPOD at the retinal location of the test light. The alternation frequency must be optimized for each subject and the test stimuli used at each locus.

Each eye was tested randomly to minimize any potential order effect. Figure 1 shows that the targets used for measuring MPOD at 0.25° was a solid disc of 15 min arc radius, at 0.50° was a solid disc of 0.5° arc radius, at 1.00° was an annulus with inner radius 50 min arc and outer radius 70 min arc, and at 1.75° foveal eccentricities was an annulus with inner radius 90 min arc and outer radius 120 min arc. The parafoveal measurement was taken by asking the subjects to fixate on a red light located precisely at 7° from the central fixation. Subjects requiring distance-refractive error correction were provided the correction in trial frames or were allowed to wear their spectacles if the visual acuity achieved was 20/20.

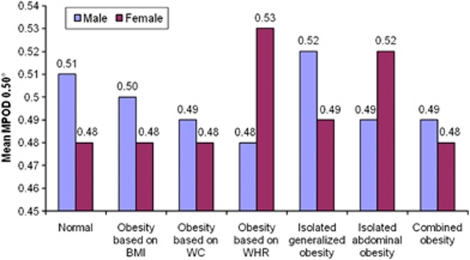

Figure 1.

Gender-wise comparison of MPOD in various types of obesity at 0.50° eccentricity.

A small black dot was present at the centre of the solid discs as a fixation aid and a fixation target of 5 min arc radius was centered within each annulus for the same. The subject was asked to fixate on the centre of the circular test stimulus superimposed near the centre of a 6.00°, 1.5 log Td, 470-nm circular blue background for the foveal measurements. The wavelength composition of the test stimulus alternated between 460 nm (peak macular pigment absorbance) and a 540 nm, 1.7 log Td reference field (minimal macular pigment absorbance) in a yoked manner. The subjects were given training till they were able to confidently recognize the null zone (ie, zone of no/minimal flicker).

The starting flicker frequency was set at 10–11 Hz. If the subject was unable to find a zone of no/minimal flicker, this frequency was increased until a zone of no/minimal flicker could be identified. If the null zone was wide, the flicker frequency was reduced. The flicker frequency was adjusted till the subject found a narrow null zone. For participants who had difficulty adjusting the knob on their own, we performed the task on their behalf, instructing the subject to notify us immediately upon cessation of the flicker sensation. A minimum of three readings (radiance measurements of the 460 nm light which provides null zone) was taken at each eccentricity, and the time taken by the subject to complete the test was also recorded.

Subjects were constantly instructed to blink several times and to continue adjusting the knob, until the blinking no longer allowed the sensation of flickering in the test targets to resume. Readings were deemed reliable and included in the study only if the standard deviation of the readings (radiance measurements of the 460 nm light which provides null zone) did not exceed 0.20.

MPOD was measured using the formula, MPOD=−log10 (Rf/Rp), where Rf is the radiance of the 460 nm light needed for null zone at the foveal location being measured, and Rp is the radiance for a null zone at the reference location in the parafovea, where MPOD is negligible. (The MPOD is derived by subtracting the log foveal sensitivity from the log parafoveal sensitivity, measured at 7°-parafoveal reference point). It was calculated using the software provided by the ‘Macular metrics Corp.', which fits an exponential function to the data and plots the spatial profile of the subject's MPOD.

MPOD measurements were repeated in 32 eyes to assess the inter-sessional variability of the readings.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements including weight, height, and waist and hip measurements were obtained using standardized techniques. Height was measured with a tape to the nearest centimetre. Subjects were requested to stand upright without shoes with their back against the wall, heels together and eyes directed forward. Weight was measured with a traditional spring balance that was kept on a firm horizontal surface. Subjects were asked to wear light clothing, and weight was recorded to the nearest 0.5 kg. BMI was calculated by using the following formula: weight (kg)/height (m)2. Waist circumference was measured by using a non-stretchable measuring tape. The subjects were asked to stand erect in a relaxed position with both feet together on a flat surface; one layer of clothing was accepted. Waist girth was measured as the smallest horizontal girth between the costal margins and the iliac crests at minimal respiration. Hip was taken as the greatest circumference (the widest protrusion of the hip) on both the sides; measurements were made to the nearest centimetre. WHR was calculated by dividing the WC (cm) by the hip circumference (cm).

Definitions

Obesity

Using the WHO Expert Consultation guidelines, obesity was defined based on BMI alone (BMI≥23 kg/m2), based on WC alone (WC≥90 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women), and based on WHR alone (≥0.90 for men and ≥0.85 for women).23, 24

Isolated generalized obesity

Isolated generalized obesity was defined as BMI≥23 kg/m2 and WC<90 cm in men and <80 cm in women (increased BMI, normal WC).

Isolated abdominal obesity

Isolated abdominal obesity was defined as BMI<23 kg/m2 and WC≥90 cm in men and ≥80 cm in women (increased WC, normal BMI).

Combined obesity (generalized+abdominal)

Combined obesity was defined as BMI≥23 kg/m2 and WC≥90 cm in men and ≥80 cm in women (increased BMI, increased WC).25

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A 95% confidence interval was chosen to denote statistical significance. Descriptive statistics were obtained for all the quantitative parameters. Comparison of group means was obtained by using the Student's t-test, one-way ANOVA, and the Mann–Whitney U-test for normally and non-normally distributed parameters. The test–retest repeatability was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (Cronbach's α), and the agreement between the MPOD measurements obtained at first and repeat sessions were assessed with the Bland and Altman plots.

Results

The baseline characteristics of 161 study subjects are shown in Table 1. In total, 51% were men. The overall mean age was 43.92±14.75 years. Men had significantly lower BMI (22.9 vs 24.9, P=0.001), lower hip circumference (94.3 vs 98.9, P=0.002), higher WC (85.5 vs 80.3, P=0.001), and higher WHR (0.91 vs 0.81, P<0.0001). Prevalence of obesity based on WC was significantly lower in men as compared with women (36.6% vs 55.7%, P=0.015), as was combined obesity (32.9% vs 51.9%, P=0.015); and that defined by WHR was more in men (58.5% vs 27.8%, P<0.0001). Mean MPOD at 0.25°, 0.50°, 1.00°, and 1.75° eccentricities was not significantly different between men and women, although in both the genders, MPOD was noted to decline with increasing distance from the centre of the fovea.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Variables | Men (n=82) | Women (n=79) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.4±15.4 | 43.4±14.1 | 0.658 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.9±3.3 | 24.9±3.9 | 0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 85.5±10.3 | 80.3±9.4 | 0.001 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 94.3±7.8 | 98.9±10.7 | 0.002 |

| Obesity based on BMI | 43 (52.4) | 51 (64.6) | 0.119 |

| Obesity based on WC | 30 (36.6) | 44 (55.7) | 0.015 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.91±0.06 | 0.81±0.09 | <0.0001 |

| Obesity based on WHR | 48 (58.5) | 22 (27.8) | <0.0001 |

| Isolated generalized obesity | 16 (19.5) | 10 (12.7) | 0.237 |

| Isolated abdominal obesity | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.8) | 1.000 |

| Combined obesity | 27 (32.9) | 41 (51.9) | 0.015 |

| Mean MPOD | |||

| 0.25° | 0.64±0.24 | 0.63±0.22 | 0.69 |

| 0.50° | 0.49±0.23 | 0.48±0.2 | 0.59 |

| 1.00° | 0.38±0.21 | 0.36±0.17 | 0.595 |

| 1.75° | 0.21±0.17 | 0.21±0.14 | 0.94 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MPOD, macular pigment optical density; WC, waist circumference; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio. P-values in bold represent significance of <0.05.

Table 2 shows the distribution of MPOD in various types of obesity at the four eccentricities from the fovea. Mean MPOD values did not significantly differ in various types of obesity, when compared with the normal subjects.

Table 2. MPOD in various types of obesity at different eccentricities from fovea.

| Variables | n |

0.25° |

0.50° |

1.00° |

1.75° |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | P-value | Mean±SD | P-value | Mean±SD | P-value | Mean±SD | P-value | ||

| Normal | 48 | 0.63±0.21 | Ref | 0.49±0.21 | Ref | 0.39±0.18 | Ref | 0.22±0.14 | Ref |

| Obesity based on BMI | 94 | 0.64±0.22 | 0.795 | 0.49±0.21 | 1.000 | 0.37±0.19 | 0.547 | 0.20±0.15 | 0.400 |

| Obesity based on WC | 74 | 0.62±0.23 | 0.809 | 0.49±0.21 | 1.000 | 0.35±0.19 | 0.249 | 0.20±0.16 | 0.500 |

| Obesity based on WHR | 70 | 0.64±0.22 | 0.805 | 0.49±0.21 | 1.000 | 0.36±0.19 | 0.253 | 0.21±0.16 | 0.700 |

| Isolated generalized obesity | 26 | 0.69±0.19 | 0.229 | 0.50±0.19 | 0.840 | 0.41±0.16 | 0.637 | 0.22±0.13 | 1.000 |

| Isolated abdominal obesity | 6 | 0.57±0.18 | 0.507 | 0.50±0.20 | 0.912 | 0.39±0.21 | 1.000 | 0.29±0.19 | 0.300 |

| Combined obesity | 68 | 0.62±0.23 | 0.812 | 0.48±0.22 | 0.806 | 0.35±0.19 | 0.256 | 0.19±0.15 | 0.300 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MPOD, macular pigment optical density; WC, waist circumference; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

Figure 1 shows the comparison between the mean MPOD among men and women at the 0.50° foveal eccentricity in all the types of obesity. There was no significant difference in mean MPOD between both the genders in any type of obesity at 0.50° eccentricity.

On evaluating the association between mean MPOD and various types of obesity in different age groups, there was no significant difference in mean MPOD values in the age groups <30, 30–40, 40–50 and 50–60 years. However, in age group ≥60 years, mean MPOD values were significantly higher in subjects with obesity based on BMI (0.61 vs 0.41, P=0.036), obesity based on WHR (0.67 vs 0.41, P=0.007), and isolated generalized obesity (0.66 vs 0.41, P=0.045) in comparison with normal subjects at 0.25° eccentricity. Subjects with obesity based on WHR also had significantly higher MPOD at 1.75° eccentricity than normal subjects in the age group ≥60 years (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to study the relationship between MPOD and obesity in the South-Indian population. It has been shown earlier that anthropometric measures, such as BMI, WHR, and WC, are not comparable across different racial populations.22 This raises an important concern regarding the use of single index for defining obesity across different races and predicting risk associated with obesity based on it. Asian population has a higher tendency towards abdominal obesity19, 20, 21, 22 and higher WHR.22 WC19 and WHR22 are reported to be better markers of obesity-related risks in this population than BMI, and both were also found to be associated with an increased risk for progression to advanced AMD.8 Furthermore, gender differences have been noted in the different obesity types in this population.19 Hence, we divided the obese subjects in various groups using different definitions of obesity25 and then we studied the distribution of MPOD at different eccentricities in each of this group, and compared the values with those of normal subjects.

Obesity, as defined by WC and combined obesity, was more prevalent in women than in men and that defined by WHR was more common in men. In our previous study in subjects with type 2 diabetes aged >40 years, we reported higher prevalence of obesity defined by BMI and by WC in women than men.25 Other population-based studies also found a similar trend.19, 26 As previously reported,27 we also noted a decline in MPOD with increasing distance from the centre of the fovea.

In the present study, we did not find any significant difference in MPOD in different types of obesities when compared with the normal subjects. Johnson et al15 also found no significant association of BMI, fat-free mass, and percentage body fat with MPOD. Hammond et al16 reported an inverse relationship among MPOD, BMI, and percentage of body fat. However, this relationship was present only at BMI>29 kg/m2 and body fat>27%. Nolan et al,17 on the other hand, reported that MPOD was inversely and significantly related to percentage of body fat and BMI (using BMI cutoff of 30) in males, even after correcting for age and dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin. However, no such significant relationship was noted in the females. In the present study, obesity was defined by BMI>23 kg/m2 using the WHO Expert Consultation guidelines.23, 24 The different cutoff of BMI can be the main reason for the discrepancy between our study and other studies.16, 17 Hammond et al16 also reported that there was no relationship between MPOD and adiposity when only subjects with a BMI below 29 and body fat below 27% were considered. Furthermore, they measured the MPOD at only one location in fovea, whereas we measured the MPOD at four different locations (eccentricities).16

Hammond et al16 hypothesized two possible explanations for a proposed inverse relationship between MPOD and obesity. First was that adipose tissue could compete with the retina for uptake of lutein and zeaxanthin, resulting in less incorporation in the retina and lower MPOD. However, women with significantly higher BMI than men had no significant difference in MPOD in the present study. A similar finding of higher percentage body fat in women and similar MPOD as in men has been reported earlier.15 Furthermore, as previously reported, the miniscule size of the retina when compared with total body fat, irrespective of the obesity status, questions the plausibility of such a hypothesis.17 The second factor that was suggested to be responsible was the subjects' dietary patterns. However, the authors themselves reported this factor alone to be insufficient to explain the significant association between MPOD and obesity.16

In the present study, the insignificant association between MPOD and obesity persisted on gender and age group-wise analysis. Hammond et al16 also found no gender relationship between MPOD and obesity, though Nolan et al17 reported a gender difference. Nolan et al17 also reported a significant age-related decline in MPOD for both males and females, which, after correction for body fat, persisted for males only. In the present study, the MPOD was noted to be higher after 60 years of age at 0.25° eccentricity. However, clinical significance of this finding, if any, seems little only.

In the present study, we report lack of an association between MPOD and obesity in the South-Indian population, using different obesity indices. A number of studies have shown that migrant Asian Indians differ markedly from the White populations in their body size–body fat relationship, with substantially higher body fat percentages seen in the former at similar BMI values.28 Hence, the findings of present study can also be generalized to these Asian migrant populations throughout the world. Other strengths of our study include large sample size and the largest database from an Asian population. The limitations include lack of measurement of serum and adipose tissue concentrations of lutein and zeaxanthin.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Eye website (http://www.nature.com/eye)

Supplementary Material

References

- Beatty S, Boulton M, Henson D, Koh H-H, Murray IJ. Macular pigment and age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:867–877. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.7.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Rimm EB, Seddon J, Giovannucci EL, Chasan-Taber L, Spiegelman D. A prospective study of carotenoid intake and risk of cataract extraction in US men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:517–524. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasan-Taber L, Willett WC, Seddon JM, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Colditz GA. A prospective study of carotenoid and vitamin A intakes and risk of cataract extraction in US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:509–516. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan LA, Lau JM, Stein EA. Carotenoid compositions and relationships in various human organs. Clin Physiol Biochem. 1990;8:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir GJ, Balashova OA, Balashova NA, Bernstein PS. Lutein and zeaxanthin are present in significant quantities in the non-macular tissues of the human eye. Exp Eye Res. 2001;72:215–223. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeum KY, Taylor A, Tang G, Russell RM. Measurement of carotenoids, retinoids, and tocopherols in human lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:2756–2761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JA. Serum levels of vitamin A and carotenoids as reflectors of nutritional status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;73:1439–1444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JM, Cote J, Davis N, Rosner B. Progression of age-related macular degeneration associated with body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-hip ratio. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:785–792. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith W, Mitchell P, Leeder SR, Wang JJ. Plasma fibrinogen levels, other cardiovascular risk factors, and age-related maculopathy. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:583–587. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunness JS, Gonzalez-Baron J, Bressler NM, Hawkins B, Applegate CA. The development of choroidal neovascularization in eyes with the geographic atrophy form of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:910–919. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00509-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcourt C, Michel F, Colvez A, Lacroux A, Delage M, Vernet MH. Associations of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors with age-related macular degeneration: the POLA study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2001;8:237–249. doi: 10.1076/opep.8.4.237.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein B, Klein R, Lee K, Jensen S. Measures of obesity and age related eye diseases. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2001;8:251–262. doi: 10.1076/opep.8.4.251.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group Risk factors associated with age-related macular degeneration: a case-control study in the Age-Related Eye disease study: Age-Related Eye Disease Study Report Number 3. Ophthalmology. 2004;107:2224–2232. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00409-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handelman GJ, Snodderly DM, Krinsky NI, Russett MD, Adler AJ. Biological control of primate macular pigment: biochemical and densitometric studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:257–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EJ, Hammond BR, Yeum KJ, Qin J, Wang XD, Castaneda C. Relation among serum and tissue concentrations of lutein and zeaxanthin and macular pigment density. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1555–1562. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond BR, Ciulla TA, Snodderly DM. Macular pigment density is reduced in obese subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan J, O'Donovan O, Kavanagh H, Stack J, Harrison M, Muldoon A, et al. Macular pigment and percentage of body fat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3940–3950. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares JA, LaRowe TL, Snodderly DM, Moeller SM, Gruber MJ, Klein ML, et al. CAREDS Macular Pigment Study Group and Investigators Predictors of optical density of lutein and zeaxanthin in retinas of older women in the Carotenoids in Age-Related Eye Disease Study, an ancillary study of the Women's Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1107–1122. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deepa M, Farooq S, Deepa R, Manjula D, Mohan V. Prevalence and significance of generalized and central body obesity in an urban Asian Indian population in Chennai, India (CURES: 47) Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:259–267. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Russell-Aulet M, Mazariegos M, Burastero S, Thornton JC, Lichtman S, et al. Body fat by dual photon absorptiometry (DPA): comparisons with traditional methods in Asians, Blacks and Caucasians. Am J Hum Biol. 1992;4:501–510. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1310040409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji MA, Faridi N, Alturi R, Chaiken RL, Lebovitz HE. Body composition, visceral fat, leptin and insulin resistance in Asian Indian men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:137–144. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raji A, Seely EW, Arky RA, Simonson DC. Body fat distribution and insulin resistance in healthy Asian Indians and Caucasians. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5366–5371. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.11.7992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Expert Consultation Appropriate body mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . The Asia Pacific Perspective, Redefining Obesity and its Treatment: International Association for the Study of Obesity and International Obesity Task Force. International Diabetes Institute: Melbourne; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Raman R, Rani PK, Gnanamoorthy P, Sudhir RR, Kumaramanikavel G, Sharma T. Association of obesity with diabetic retinopathy: Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetics Study (SN-DREAMS Report no. 8) Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Yeo PP, Lun KC, Thai AC, Wang KW, Cheah JS. Obesity and body mass indices in Chinese, Malays and Indians in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1990;19:333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond BR, Jr, Wooten BR, Snodderly DM. Individual variations in the spatial profile of human macular pigment. J Opt Soc Am A. 1997;14:1187–1196. doi: 10.1364/josaa.14.001187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deurenberg-Yap M, Deurenberg P. Is a re-evaluation of WHO body mass index cut-off values needed? The case of Asians in Singapore. Nutr Rev. 2003;61:S80–S87. doi: 10.1301/nr.2003.may.S80-S87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.