Abstract

Background

Among intermediate to high-risk patients with chest pain, we have shown that a cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) stress-test strategy implemented in an observation unit (OU) reduces 1-year healthcare costs compared to inpatient care. In this study, we compare two OU strategies to determine among lower-risk patients if a mandatory CMR stress test strategy was more effective than a physicians’ ability to select a stress test modality.

Methods and Results

Upon ED arrival and referral to the OU for management of low to intermediate-risk chest pain, 120 individuals were randomized to receive an a) CMR stress imaging test (n=60), or b) a provider selected stress test (n=60: stress echo [62%], CMR (32%), cardiac catheterization (3%), nuclear (2%), and coronary CT [2%]). No differences were detected in length of stay (median CMR = 24.2 hours vs 23.8 hours, p=0.75), catheterization without revascularization (CMR=0% vs 3%), appropriateness of admission decisions (CMR 87% vs 93%, p=0.36), or 30-day ACS (both 3%). Median cost was higher among those randomized to the CMR mandated group ($2005 vs $1686, p<0.001).

Conclusions

In patients with lower-risk chest pain receiving ED-directed OU care, the ability of a physician to select a cardiac stress imaging modality (including echocardiography, CMR, or radionuclide testing) was more cost effective than a pathway that mandates a CMR stress test. Contrary to prior observations in individuals with intermediate to high-risk chest pain, in those with lower risk chest pain, these results highlight the importance of physician-related choices during ACS diagnostic protocols.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT00869245.

Keywords: chest pain diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging, trials, cost-benefit analysis

Recent investigations of stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) in patients with acute chest pain have demonstrated high accuracy for ACS and established the ability of CMR to diagnose recent infarction, detect inducible ischemia, and predict 1-year prognosis in patients presenting to the emergency department (ED).1,2 A previous clinical trial among patients with chest pain at intermediate or high-risk for ACS demonstrated that cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging combined with observation unit (OU) care reduces cost at 1-year without a difference in outcomes compared to inpatient management.3,4 However, most commonly lower-risk patients are managed in OUs where they have been shown to decrease the cost of care and are associated with low rates of short-term acute coronary syndrome (ACS) after discharge.5–7 In lower risk patients receiving care in an OU, it is unclear whether a mandatory CMR stress imaging strategy would be more effective than the current OU strategy whereby care providers choose among various stress imaging strategies.

The objective of this clinical trial was to determine the relevant comparison of a mandatory stress CMR versus a provider determined stress testing strategy (provider choice or PC) in an OU setting in patients with lower-risk chest pain. To assess this objective, we compared these two imaging strategies primarily on efficiency, measured as length of stay, and secondarily on cost and efficacy, measured as cardiac catheterizations without coronary intervention, appropriateness of cardiovascular admission decisions, and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Study design

We performed a single center randomized clinical trial. After approval by the institutional review board of Wake Forest School of Medicine and obtaining extramural funding, all participants provided written informed consent. The trial was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00869245) prior to participant recruitment. The trial was distinct from a previously reported clinical trial3,4 and both trials did not enroll simultaneously.

Study setting and population

The study population consisted of patients presenting to the Emergency Department of the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center with acute chest pain or related symptoms concerning for ACS. Eligibility criteria were designed to enroll participants representative of those commonly managed in US chest pain observation units at low to intermediate risk for ACS, excluding those at very high or very low risk for ACS.

The risk assessment for eligibility required that the patient have either a Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI)8 risk score ≥ 1 or a physician impression that the participant exhibited an intermediate likelihood of ACS. The risk assessment also included care provider assessments that the patient required an inpatient or OU evaluation for their chest pain, that coronary arteriogram (either by invasive angiography or CT angiography) was not indicated at the time of enrollment, and that the patient was safe for OU care. Patients with multiple prior stents, multiple prior MIs, or PCI / CABG in the past 6 months were not considered safe for OU care.

Additional eligibility criteria included age ≥18 years; Patients were ineligible for enrollment if they exhibited an initial elevation of troponin I above the decision threshold (> 1.0 ng/ml), new ST-segment elevation or depression, contraindications to CMR, inability to lie flat, hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmhg), renal insufficiency (estimated GFR <45 cc/min), life expectancy < 3 months, pregnancy, solid organ transplant, chronic liver disease, or refused medical record review and follow-up at 30 days.

Randomization

Randomization was stratified to ensure equal distribution of key covariates thought to be related to length of stay; these measures were time of ED presentation (6a-3p or 3p-6a) and established coronary disease (yes or no). To ensure equal accrual among study groups within the 4 strata, a blocked randomization sequence of randomly varying size (2, 4, or 6) was created. The randomization sequences were generated using SAS v9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and given to a staff member not involved in participant recruitment. This staff member assigned each randomization sequence to one of the four strata and used this sequence to create bins of numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes.

Study groups

Participants were randomized to receive OU care with either stress CMR imaging (OUCMR) or provider choice (PC) care whereby imaging was determined by the care provider. All participants had orders placed for serial cardiac markers and ECGs at 0, 4h, and 8h from ED arrival. Prior to conducting stress imaging, patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) were detected with serial cardiac markers or resting CMR imaging as described below. Patients with ongoing ischemic symptoms including resting angina were managed in the coronary care unit and not eligible for this study. Non-invasive imaging was conducted during the index visit as per standard care at the study institution. Non-invasive imaging options available included stress (pharmacologic or exercise) echocardiography, stress nuclear imaging, stress CMR, and coronary CT angiography (CCTA). According to previously published techniques, CCTA images with calcium scoring were obtained with a 64-slice LightSpeed VCT (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI).9 Nuclear imaging was performed using single-photon emission computed tomography with rest and stress injections of technetium 99m-tetrofosmin (Myoview, GE healthcare). Stress echocardiography was performed with either treadmill or dobutamine stress in a laboratory accredited by the Intersocietal Commission for the Accreditation of Echocardiography Laboratories. All imaging modalities are available from 8am–5pm weekdays. After randomization, care was determined by the care providers. Cardiology consultations were available in both arms based on clinical need.

CMR imaging sequence

CMR imaging was conducted using vasodilator (adenosine) stress unless contraindicated in which case dobutamine stress was performed. Rest imaging and visualization of the thoracic aorta and proximal pulmonary arteries through the second bifurcation were conducted prior to stress imaging. Imaging sequences included resting wall motion, T2-weighted imaging to assess for myocardial edema, stress perfusion, rest perfusion, and delayed enhancement (Table 1.) Imaging interpretation was performed by board certified radiology and cardiology faculty with at least level 2 training in CMR.10

Table 1.

Typical imaging parameters for CMR participants

| Scan | Views | Pulse Sequence | Imaging Matrix | FOV (mm) | Slice Thickness (mm) | TE (ms) | TR (ms) | Flip Angle (deg) | Band-width (Hz/pix) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting wall motion | 2, 3, 4 chamber and 3 LV short axis views | Cine SSFP | 192×156 | 360 | 7 | 1.2 | 40 | 80 | 930 |

| T2 dark blood (body coil) | 2, 3, 4 chamber and 3 LV short axis views | IR turboSE (2RR) | 256×162 | 360 | 10 | 66 | 658 | 60/ 200 | 780 |

| T2 Prep (body coil) | 2, 3, 4 chamber and 3 LV short axis views | IR turbo-GRE | 160×104 | 340 | 8 | 1.1 | 250 | 70 | 930 |

| Contrast injection (gadobenate dimeglumine 0.05 mmol/kg) and stress agent infusion (adenosine) | |||||||||

| Stress perfusion | 3 LV short axis views | Turbo-GRE | 192×108 | 360 | 8 | 1.1 | 170 | 12 | 650 |

| Contrast injection (gadobenate dimeglumine 0.05 mmol/kg) | |||||||||

| Rest perfusion | 3 LV short axis views | Turbo-GRE | 192×108 | 360 | 8 | 1.1 | 170 | 12 | 650 |

| Delayed enhancement | 2, 3, 4 chamber and 10 short axis views | IR GRE 300 TI | 192×140 | 320 | 8 | 3.3 | 800 | 25 | 130 |

FOV=Field of View TR=Repetition Time TE=Echo Time LV=Left Ventricle IR=Inversion Recovery TI=Inversion Time GRE = Gradient echo

Participant follow-up and outcomes

Participants underwent a structured record review and a telephone interview using a structured script at 30 days to determine outcomes. Additional information on data handling is available in the Supplemental Materials.

The primary outcome was length of stay, defined as the difference between the time of ED arrival and discharge from the hospital. Secondary outcomes included the appropriateness of the observation unit disposition decision and cardiac catheterizations not leading to coronary intervention (non-therapeutic cardiac catheterizations). The appropriateness of disposition decisions has been previously used to determine the impact of imaging on chest pain triage.11 Correct dispositions were considered patients discharged home without an ACS event at 30 days or admitted and experiencing an ACS event within 30 days.

The outcomes of ACS and MI were adjudicated by two board certified emergency physicians blinded to the patient’s study group. ACS was defined as acute MI, ischemia symptoms leading to revascularization, death likely related to cardiac ischemia, or a discharge diagnosis of definite or probable unstable angina with evidence of coronary stenosis > 70% or inducible ischemia on stress testing in subjects not undergoing cardiac catheterization. Diagnosis of acute MI included either autopsy findings of acute MI or a typical rise and fall of troponin I (>1.0 ng/dl) with one of the following: ischemic symptoms, development of pathologic Q waves, ST-segment elevation or depression, or coronary artery intervention. Troponin I assays during the study period were the TnI-Ultra™ (ADVIA Centaur platform, Siemens) or the Access® AccuTnI™ Troponin I (dxi800s platform, Beckman Coulter).

The cost of the index hospital visit was calculated based on individual patient charges as previously described by this study team.3 For all payers, itemized hospital charges from each participant were converted to cost using departmental-specific cost to charge ratios used to file reports with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services annually. Provider charges were converted to cost by calculating work-related relative value units for services provided, and then converting these to cost using the Medicare conversion factor.

The sample size for this trial was chosen to provide adequate power to detect a difference in length of stay, the primary outcome of this trial. A model was constructed using preliminary data for lengths of stay, estimating the number of patients in each arm able to undergo same day imaging, and accounting for the accuracy of the imaging modalities. This model suggested a 7.8 hour reduction in length of stay might be associated with CMR testing. Standard deviation for length of stay was estimated at 13.0 hours based on the first 10 participants receiving OUCMR care in a previous study.3 Using this information, we calculated that 120 patients would provide 90% power with a 2-sided alpha of 0.05 using linear regression to detect a 7.8 hour difference in mean length of stay.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data were examined to assess distributions of outcome variables and key covariates. Presenting characteristics, raw length of stay intervals, cost, proportion of correct dispositions and non-therapeutic cardiac catheterizations of the study groups were examined using Chi-square and Fisher exact tests for proportions, t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, and Kruskal-Wallis tests for non-normal continuous variables based on intention to treat. The outcome variables length of stay and cost were found to have skewed distributions. These variables were modeled using the log transform in PROC MIXED adjusting for the two randomization strata, demographics and presenting characteristics.

Results

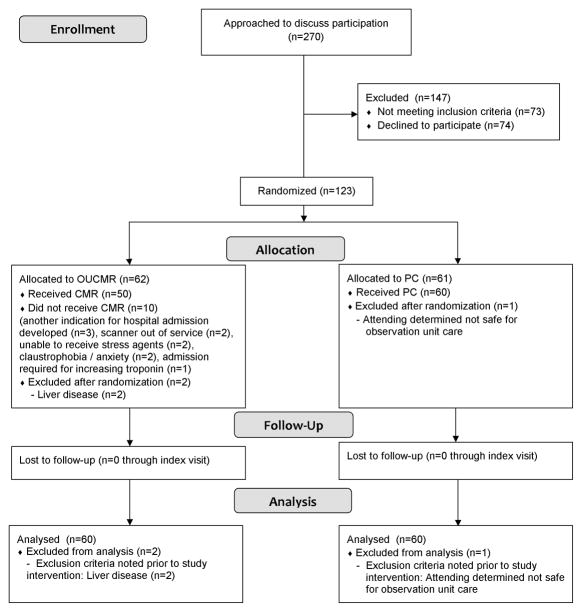

Over 18 months of screening, 270 patients were approached; of these, 73 met exclusion criteria 74 declined participation, and 123 consented to participate and were randomized (Figure 1). Common reasons for exclusion were contraindications to MRI (n=26) and not suitable for observation unit care (n=13). Soon after randomization, 3 participants were found to have exclusions (liver disease (n=2), physician determination that the patient was not safe for OU care (n=1)) representing protocol deviations. Due to safety concerns, these participants were withdrawn from the study protocol prior to any study interventions and excluded from analysis. One additional protocol deviation occurred due to the care provider’s intent to order a coronary CT. This was not a safety concern; the participant was not withdrawn from the study protocol and was included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Randomization groups did not differ in terms of all baseline characteristics of interest (Tables 2 and 3). The mean age of participants was 53 +/− 11 years, with 15% > 65 years in age. Prior MI was confirmed in 4% of participants, and a previous diagnosis of heart failure was confirmed in 3%. Cardiac testing performed is shown in Table 4. In the CMR group, all participants had an initial order placed for stress CMR; 10 (17%) participants did not receive CMR due to anxiety / claustrophobia (n=2), unable to receive stress agents (n=2), scanner out of service (n=2), admission required for increasing troponin (n=1), or another indication for hospital admission developed (n=3).

Table 2.

Participant Demographics and Past Medical History

| Patient Characteristics | PC | OUCMR |

|---|---|---|

| n / N (%) | n / N (%) | |

| Age (yrs)* | 53.1(9.9) | 53.4(11.6) |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 7/60 (12) | 11/60 (18) |

| Female sex | 33/60 (55) | 36/60 (60) |

| White race | 39/60 (65) | 35/60 (58) |

| Hypertension | 33/59 (56) | 37/58 (64) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12/60 (20) | 15/60 (25) |

| Current smoking | 22/60 (37) | 22/60 (37) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 27/59 (46) | 32/60 (54) |

| Prior Heart Failure, confirmed | 2/58 (4) | 2/59 (3) |

| Established CAD, confirmed | 4/58 (7) | 3/59 (5) |

| Prior MI, confirmed | 3/58 (5) | 2/60 (3) |

| Prior revascularization, confirmed | 1/60 (2) | 1/60 (2) |

| Prior CABG | 0/60 (0) | 1/60 (2) |

data presented as mean(SD); CABG = Coronary artery bypass graft; CAD = Coronary artery disease; MI = myocardial infarction; OUCMR = Observation unit cardiac magnetic resonance;

Table 3.

Presenting Characteristics and Physical Exam Findings

| PC | OUCMR | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n / N, (%) | n / N, (%) | ||

| Presenting Characteristics | |||

| Chest pain chief complaint‡ | 56/60 (93) | 54/60 (93) | 1.00 |

| Chest pain at rest‡ | 50/60 (83) | 50/57 (88) | 0.60 |

| Multiple episodes of symptoms within 24 hours§ | 37/60 (62) | 36/58 (62) | 0.96 |

| Chest pain present on arrival to the ED§ | 33/60 (55) | 39/58 (67) | 0.17 |

| Chest pain pleuritic‡ | 5/60 (8) | 9/58 (16) | 0.27 |

| Physical Exam | |||

| Heart rate (beats/min)* | 81(13) | 79 (11) | 0.32 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg)* | 145(17) | 149(22) | 0.27 |

| Murmur‡ | 0/57 (0) | 1/54(2) | 0.49 |

| Rales | 0/60 (0) | 0/58 (0) | |

| JVD | 0/60 (0) | 0/57 (0) | |

| Chest pain reproducible‡ | 4/57 (7) | 8/54 (15) | 0.23 |

| Overall ECG classification | 0.26 | ||

| Normal | 36/60 (60) | 38/60 (63) | |

| Nonspecific changes | 13/60 (22) | 18/60 (30) | |

| Early repolarization only | 1/60 (2) | 0/60 (0) | |

| Abnormal but not diagnostic of ischemia | 4/60 (7) | 3/60 (5) | |

| Infarction or ischemia known to be old | 2/60 (3) | 1/60 (2) | |

| Infarction or ischemia not known to be old | 4/60 (7) | 0/60 (0) | |

| Suggestive of acute MI | 0/60 (0) | 0/60 (0) | |

| Risk Stratification | |||

| ED physician assessment of % likelihood of ACS within 30 days† | 5 (4–10) | 8 (5–10) | 0.58 |

| ED Physician overall impression‡ | | | 0.08 | ||

| Acute MI | 1/60 (2) | 0/57 (0) | |

| Unstable angina | 4/60 (7) | 12/57 (21) | |

| Atypical | 47/60 (78) | 38/57 (67) | |

| Non-ischemic | 8/60 (13) | 7/57 (12) | |

| TIMI risk score‡ | 0.18 | ||

| 0 | 5/60 (8) | 3/60 (5) | |

| 1 | 24/60 (40) | 15/60 (25) | |

| 2 | 21/60 (35) | 28/60 (47) | |

| 3 | 7/60 (12) | 13/60 (22) | |

| 4 | 3/60 (5) | 1/60 (2) | |

| 5 | 0/60 (0) | 0/60 (0) | |

data presented as mean(SD) and analyzed with t-test;

data presented as median(1st quartile, 3rd quartile) and analyzed with Kruskal-Wallis test;

Fisher exact test;

chi-squared test;

provider impression obtained before noninvasive cardiac imaging;

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; ED = emergency department; MI = myocardial infarction; OUCMR = Observation unit cardiac magnetic resonance; TIMI = thrombolysis in myocardial infarction;

Table 4.

Cardiac Testing and Clinical Outcomes During Index Hospital

| PC | OUCMR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First cardiac imaging test | Ordered | Performed | Ordered | Performed† | |

| n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | ||

| Stress CMR | 18 / 60 (30) | 19 / 60 (32) | 60 / 60 (100) | 50 / 60 (83) | |

| Exercise treadmill echo | 26 / 60 (43) | 27 / 60 (45) | 0 / 60 (0) | 5 / 60 (8) | |

| Dobutamine echo | 14 / 60 (23) | 10 / 60 (17) | 0 / 60 (0) | 1 / 60 (2) | |

| Stress nuclear imaging | 1 / 60 (2) | 1 / 60 (2) | 0 / 60 (0) | 0 / 60 (0) | |

| Cardiac catheterization | 0 / 60 (0) | 2 / 60 (3) | 0 / 60 (0) | 1 / 60 (2) | |

| Coronary CT angiography | 1 / 60 (2) | 1 / 60 (2) | 0 / 60 (0) | 0 / 60 (0) | |

| Median time to first cardiac imaging test (hours)* | 20.5 (16.4, 22.3) | 19.7 (8.9, 24.2) | |||

| PC | OUCMR | P value‡ | |||

| Noninvasive cardiac imaging after initial imaging test | 3 / 60 (5) | 5 / 57 (9) | 0.48 | ||

| Cardiac catheterization after initial imaging test | 1 / 60 (2) | 1 / 57 (2) | 1.00 | ||

| Clinical outcomes‡ | |||||

| Acute coronary syndrome through 30 days | 2 / 60 (3) | 2 / 60 (3) | 1.00 | ||

| Cardiovascular death | 0 / 60 (0) | 0 / 60 (0) | - | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 2 / 60 (3) | 1 / 60 (2) | 1.00 | ||

| Revascularization | 1 / 60 (2) | 2 / 60 (3%) | 1.00 | ||

= data presented as median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile);

3 patients did not have any cardiac testing;

Data from all participants are included based on results of telephone follow-up and / or record review and are presented as the number of participants with at least 1 of the events;

Fisher exact test;

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; ED = emergency department; MI = myocardial infarction; OUCMR = Observation unit cardiac magnetic resonance; TIMI = thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

Efficiency

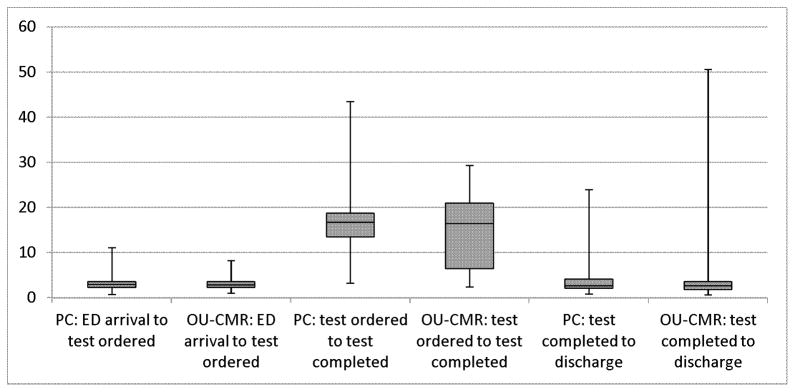

Length of stay was not statistically different between the study groups. In the CMR group, the median LOS was 24.2 hours compared to 23.8 hours in the PC group (p=0.75, Kruskal-Wallis). Length of stay was not normally distributed and therefore was log-transformed for linear regression modeling. After accounting for the two randomization strata, no additional covariates significantly contributed to the model. In the final model containing study group and the two stratification variables, there was no significant difference in LOS among groups (p=0.75, F-test from analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)). These findings did not differ when excluding PC participants undergoing CMR testing as the first test (p=0.80). Length of stay intervals by study group are shown in Figure 2. Subgroup comparisons for LOS are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Figure 2.

Boxplot of interval times by study group

No significant differences in time intervals were detected among groups (all p>0.05, Kruskal-Wallis tests).

*excludes 3 CMR participants who received no cardiac imaging

The mean costs of the index visit were $2586 for the CMR group and $2050 for the PC group; median costs were $2005 and $1686, respectively. (Table 5) Cost data were found to be rightward skewed. Significant differences among groups favoring a reduced cost for PC participants were seen when (1) comparing the log transformed data using a t-test (p=0.007), (2) regression accounting for strata, age, race, ED impression, TIMI risk score, prior MI, and prior heart failure (p=0.005), and (3) when comparing the distributions with a Kruskal-Wallis Test (p<0.001). Cost remained lower among PC participants when excluding PC participants undergoing CMR testing from the regression analysis (p<0.001) and when removing the hospital noninvasive imaging cost from all participants’ cost (p=0.03, Fisher exact comparison of log transformed data). Itemized costs are shown in Table 5. CMR participants had higher pharmacy and noninvasive imaging cost. Among participants from both groups who received CMR testing, an average pharmacy cost increase of $136 was observed compared to those not undergoing CMR consistent with the additional cost from the pharmacologic stress agent.

Table 5.

Elapsed Times, Length of Stay, Disposition, and Cost

| PC n/N (%) | OUCMR n/N (%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elapsed times | |||

| ED arrival to first cardiac imaging test ordering (hours)*† | 2.9 (2.2, 3.6) | 2.9 (2.2, 3.6) | 0.74 |

| First cardiac imaging test ordered to first cardiac imaging test completed (hours)*† | 16.7 (13.5, 18.8) | 16.4 (6.4, 21.0) | 0.60 |

| First cardiac imaging test completion to discharge (hours)*† | 2.7 (2.1, 4.1) | 2.6 (1.8, 3.5) | 0.99 |

| Total Length of stay (hours)*† | 23.8 (18.5, 27.1) | 24.2 (16.7, 28.8) | 0.75 |

| Cardiac catheterization without revascularization | 2/60 (3) | 0/60 (0) | |

| Hospital admission | 4/60 (7) | 10/60 (17) | 0.15 |

| ACS event within 30 days‡ | 1/4 (25) | 2/10 (20) | |

| Other cardiovascular emergency | 0/4 (0) | 2/10 (20) | |

| Discharge home§ | 56/60 (93) | 50/60 (83) | 0.15 |

| ACS event within 30 days‡ | 1/56 (2) | 0/50 (0) | |

| Proportion admitted without ACS or discharged from the OU with 30 day ACS§ | 4/60 (7) | 8/60 (13) | 0.36 |

| Index visit hospital cost*| | | $1431 ($1125, $1737) | $1655 ($1526, $2180) | 0.01 |

| ED services*† | $419 ($296, $594) | $454 ($329, $646) | 0.21 |

| Labs*† | $152 ($136, $168) | $150 ($134, $190) | 0.92 |

| Inpatient services*† | $0 ($0, $0) | $0 ($0, $0) | 0.02 |

| Pharmacy*† | $121 ($14, $250) | $256 ($233, $292) | <0.01 |

| Noninvasive imaging*† | $582 ($389, $835) | $815 ($757, $883) | <0.01 |

| Invasive imaging*† | $0 ($0, $0) | $0 ($0, $0) | 0.67 |

| Index visit provider cost*| | | $273 ($242, $303) | $281 ($274, $342) | 0.06 |

| Index visit total cost*| | | $1686 ($1382, $2026) | $2005 ($1787, $2483) | 0.01 |

data presented as median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile)

comparison performed with the Kruskal-Wallis test;

Data from all participants are included based on results of telephone follow-up and / or record review;

Fisher exact test;

comparison of log transformed data with a Student’s t-test;

ACS = acute coronary syndrome; ED = emergency department; MI = myocardial infarction; OUCMR = Observation unit cardiac magnetic resonance; TIMI = thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

Both groups had a very low incidence of non-therapeutic cardiac catheterizations (CMR 0% vs 3%). Cardiac catheterizations during the index visit were performed in 3 patients in the PC group, 1 resulting in PCI. In the CMR group, 2 catheterizations were performed both resulting in PCI.

Clinical outcomes

An adjudicated diagnosis of ACS occurred in 2 patients from each group within 30 days of randomization. In the CMR group, both patients had ACS during the index visit (one with PCI, on with MI and PCI). In the PC group, 1 patient had ACS during the index visit due to MI with PCI, and 1 patient had ACS after discharge due to MI.

Test performance

Cardiac testing by study group is shown in Table 4. In the CMR group, 57/60 participants had cardiac imaging with 2 tests positive for inducible ischemia or significant stenosis (≥70%); both had an adjudicated diagnosis of ACS. In the PC group, 60/60 had cardiac imaging with 2 tests positive for inducible ischemia or significant stenosis; one had an adjudicated diagnosis of ACS. The initial imaging modality performed was nondiagnostic in 6/60 CMR participants and 4/60 PC participants. Among the 48 participants in each group with complete beginning and ending times for the initial cardiac imaging test, median imaging times were 58 minutes (inter-quartile range 53, 65) in the CMR group and 43 minutes (inter-quartile range 28, 59 minutes) in the PC group. In the CMR group, 7 participants (12%) had non-ischemic findings on the initial test relevant to the acute presentation, all seen on CMR, resulting in 2 admissions. Findings included left ventricular noncompaction (n=3), pericardial effusion (n=2), pulmonary embolism (n=1), and cardiomyopathy (n=1). Non-ischemic relevant findings in the PC group on the initial test were severe global hypokinesis, pericardial effusion, and patent foramen ovale (all n=1), with the former 2 discovered on CMR; all were discharged.

Process of Care Delivery

Care providers made appropriate disposition decisions based on the occurrence of ACS in 87% of CMR participants compared to 93% of PC participants (p = 0.36). In the CMR group, inappropriate disposition decisions involved 8 participants who were admitted following OU care and did not experience ACS. Reasons for admission among these participants included to further evaluate for ACS (n=6) and treatment for pulmonary embolism (n=2). In the PC group, inappropriate disposition decisions were observed in 4 participants. These included 3 participants who were admitted to further evaluate for ACS, and did not experience ACS, and 1 participant who was discharged and later found to have ACS.

Cardiology consultations were obtained in 10 participants in the CMR group and 6 in the PC group (see Supplementary Materials for consultation reasons). Participants receiving cardiology consults had higher median cost ($2446 vs $1829, p<0.001) and longer median LOS (28.5h vs 23.7h, p=0.02). Regression analysis of log transformed data was used to adjust for consultations. After adjustment for consultations, OUCMR continued to have higher cost (p=0.01) and similar LOS (p=0.91).

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the ability of a physician to determine the cardiac stress imaging modality among a range of options including echocardiography, radionuclide imaging, and CMR for lower risk patients being managed in an OU is more effective than a mandatory CMR-based testing strategy. Increased effectiveness of the physician choice strategy was evidenced by similar length of stay, similar outcomes, and lower cost. The design of this trial differs from our previous clinical trial in that the previous trial enrolled a higher risk patient population and randomized participants to inpatient care or OU care with CMR stress testing. In those more complex patients, CMR imaging allows expansion of OU care to higher risk patients typically managed as inpatients without an increase in adverse events and while reducing cost 1 year from randomization.3,4 In the current trial, we aimed to enroll a lower risk population, typical of those managed in US OUs, and randomize to a mandatory CMR strategy versus a physician choice strategy consistent with usual care. Tables 2 and 5 display the relatively young mean age of participants in this trial, the low rate of prior cardiac events, and the low overall event rate. In these lower risk patients, it appears the physician’s ability to tailor testing to the individual patient, while considering institutional imaging strengths, may be a key to enhanced healthcare efficiency.

These findings convey an important message regarding efficient healthcare delivery. It has been suggested that variability in healthcare delivery is a driver of cost and inefficiency.12 We have shown that eliminating this variability does not necessarily lead to a decrease in cost. Previously, it has been shown that patients are better suited for different imaging studies based on gender, body habitus, etc. As an example, CMR stress testing results are highly efficacious in patients not well-suited for dobutamine stress echocardiography because of poor acoustic windows.13 In the PC group in this study, providers carefully selected the patient’s imaging modality. For instance, in PC participants with prior MIs (a group that physicians may perceive to be a higher risk of ACS), all received CMR perfusion stress imaging with techniques that could discriminate old from new infarcts. While we did not survey our physicians to collect data regarding their test preferences, the results of this study support the notion that among lower risk OU patients, physician choice is an important component to efficient care delivery.

The cost increase in the OUCMR arm was driven by increased hospital-related cost. Hospital-related costs are shown in Table 5 and demonstrate increases among OUCMR participants in pharmacy and non-invasive imaging cost. Pharmacy cost includes the stress agent (adenosine, typical cost $170–$243) and non-invasive imaging cost includes the contrast agent (gadobenate dimeglumine, typical cost $140–$190) administered during the MR exam. PC participants undergoing exercise stress exams (46%) did not accumulate similar charges. The impact of stress and contrast agents on MRI stress costs may decrease as these agents become available generically.

An uncertain component to our analysis relates to the high number (12%) of relevant ancillary findings in the CMR group. These cases added complexity, likely increased cost, yet have potential for positive effects on long term health. A larger study measuring both cost and effectiveness are required to determine if these findings are statistically more common in the CMR group, and whether they lead to an improvement in health.

The design and implementation of this trial brought forth unique challenges relating to the integration of our study intervention (CMR) into usual care. For example, CMR was commonly selected for more complicated patients in the PC arm. While reflecting “real life” decision making, this ultimately reduced the power to detect a difference in LOS. Excluding these participants would have introduced selection bias. Restricting these patients from undergoing CMR may not have been ethical. The institutional proficiency and adoption of cardiovascular imaging techniques need to be considered when designing larger cardiovascular imaging trials. There are limitations to our findings. First, the trial was conducted at a single center with extensive experience in CMR and echocardiographic imaging. We are uncertain of results using other mandated imaging strategies with other modalities. Second, the PC comparison group received stress testing with multiple modalities. This variety is reflective of typical care patterns, and is consistent with other OU publications.6,14 However, the design of this trial precludes a direct comparison of imaging modalities with one another. Third, the enrollment criteria required the care provider assessment that the patient was safe for OU care. Highly complicated patients were commonly rated as not being safe for OU care by the care providers. As a result, the study population reflects a population commonly managed in observation units in the US, but differs from the higher risk population that we previously demonstrated to be safely managed in an OU setting with OUCMR. Finally, adjustment was not made for multiple statistical comparisons. It is possible that “positive” findings could be spurious in light of the large number of tests at the 0.05 significance level.

Conclusions

In patients with lower-risk chest pain receiving ED-directed OU care, the ability of a physician to select a cardiac stress imaging modality (including echocardiography, CMR, or radionuclide testing) was more cost effective than a pathway that mandates a CMR stress test. Contrary to prior observations in individuals with intermediate to high-risk chest pain, in those with lower risk chest pain, these results highlight the importance of physician-related choices during ACS diagnostic protocols.

Supplementary Material

Short commentary on potential clinical impact.

In an effort to define a more efficient and efficacious care pathway for patients with chest pain managed in an observation unit, we examined the role of a mandatory CMR stress imaging pathway in lower risk ED patients with symptoms of ACS. In comparison to a mandatory CMR pathway, participants in a care pathway in which care providers chose the stress imaging modality (with an option for CMR) had decreased cost, similar lengths of stay, and similar clinical outcomes. The results of this randomized trial suggest that preserving the physician choice in selecting a stress modality is an important component to efficient care delivery in patients with lower-risk symptoms of ACS being managed in an emergency department-directed observation unit. These findings are in contrast to prior findings in patients at intermediate to high-risk where an observation unit strategy with stress CMR is a cost-effective alternative to inpatient care. The health policy implication of this research is that prior to instituting a mandate for a particular imaging modality, prospective studies to evaluate the impact on efficiency and cost should be performed.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

American Heart Association 0980008N (Miller), Translational Science Institute of Wake Forest School of Medicine; NIH grants 1 R21 HL097131-01A1 (Miller) and 1 R01 HL076438 (Hundley), Siemens (software support), NIH T-32 HL087730 (Mahler, PI Goff).

Footnotes

Abstract presented at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine in June 2011, Boston, MA.

Disclosures

Chadwick D. Miller, MD, MS Research grants – 3M, AHA, NIH, PA Dept Health, EKR therapeutics (significant), Johnson & Johnson / Scios Inc, Chiron Corporation, Astra Pharmaceuticals; Research support – Siemens; Other – Up-to-date, expert witness

James W. Hoekstra, MD Consultant: Sanofi-Aventis, Verathon; Advisory Boards: Merck, Ortho McNeil, Daiichi-Sankyo, Astra Zeneca

W. Gregory Hundley, MD: Research support – Bracco diagnostics; Stock / ownership – Prova, Inc.

Craig A. Hamilton PhD: Stock / ownership – Prova, Inc.

Contributor Information

Chadwick D. Miller, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

James W. Hoekstra, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Cedric Lefebvre, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Howard Blumstein, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Craig A. Hamilton, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Erin N. Harper, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Simon Mahler, Departments of Epidemiology and Prevention and Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Deborah B. Diercks, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California, Davis Medical Center.

Rebecca Neiberg, Department of Biostatistical Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

W. Gregory Hundley, Departments of Internal Medicine/Cardiology and Radiology, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Kwong RY, Schussheim AE, Rekhraj S, Aletras AH, Geller N, Davis J, Christian TF, Balaban RS, Arai AE. Detecting acute coronary syndrome in the emergency department with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2003;107:531–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047527.11221.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingkanisorn WP, Kwong RY, Bohme NS, Geller NL, Rhoads KL, Dyke CK, Paterson DI, Syed MA, Aletras AH, Arai AE. Prognosis of Negative Adenosine Stress Magnetic Resonance in Patients Presenting to an Emergency Department With Chest Pain. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47:1427–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller CD, Hwang W, Hoekstra JW, Case D, Lefebvre C, Blumstein H, Hiestand B, Diercks DB, Hamilton CA, Harper EN, Hundley WG. Stress Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging With Observation Unit Care Reduces Cost for Patients With Emergent Chest Pain: A Randomized Trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2010;56:209–219.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller CD, Hwang W, Case D, Hoekstra JW, Lefebvre C, Blumstein H, Hamilton CA, Harper EN, Hundley WG. Stress CMR Imaging Observation Unit in the Emergency Department Reduces 1-Year Medical Care Costs in Patients With Acute Chest Pain: A Randomized Study for Comparison With Inpatient Care. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2011;4:862–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts RR, Zalenski RJ, Mensah EK, Rydman RJ, Ciavarella G, Gussow L, Das K, Kampe LM, Dickover B, McDermott MF, Hart A, Straus HE, Murphy DG, Rao R. Costs of an Emergency Department--Based Accelerated Diagnostic Protocol vs Hospitalization in Patients With Chest Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 1997;278:1670–1676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farkouh ME, Smars PA, Reeder GS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW, Meloy TD, Kopecky SL, Allen M, Allison TG, Gibbons RJ, Gabriel SE The Chest Pain Evaluation in the Emergency Room (CHEER) Investigators. A Clinical Trial of a Chest-Pain Observation Unit for Patients with Unstable Angina. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1882–1888. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graff LG, Dallara J, Ross MA, Joseph AJ, Itzcovitz J, Andelman RP, Emerman C, Turbiner S, Espinosa JA, Severance H. Impact on the care of the emergency department chest pain patient from the chest pain evaluation registry (CHEPER) study. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:563–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJLM, McCabe CH, Horacek T, Papuchis G, Mautner B, Corbalan R, Radley D, Braunwald E. The TIMI Risk Score for Unstable Angina/Non-ST Elevation MI: A Method for Prognostication and Therapeutic Decision Making. JAMA. 2000;284:835–842. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller CD, Litt HI, Askew K, Entrikin D, Carr JJ, Chang AM, Kilkenny J, Weisenthal B, Hollander JE. Implications of 25% to 50% coronary stenosis with cardiac computed tomographic angiography in ED patients. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2011 Apr 25; doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.02.015. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budoff MJ, Cohen MC, Garcia MJ, Hodgson JM, Hundley WG, Lima JA, Manning WJ, Pohost GM, Raggi PM, Rodgers GP, Rumberger JA, Taylor AJ, Creager MA, Hirshfeld JW, Jr, Lorell BH, Merli G, Tracy CM, Weitz HH. ACCF/AHA clinical competence statement on cardiac imaging with computed tomography and magnetic resonance: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians Task Force on Clinical Competence and Training. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:383–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udelson JE, Beshansky JR, Ballin DS, Feldman JA, Griffith JL, Handler J, Heller GV, Hendel RC, Pope JH, Ruthazer R, Spiegler EJ, Woolard RH, Selker HP. Myocardial perfusion imaging for evaluation and triage of patients with suspected acute cardiac ischemia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2693–700. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.21.2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Baker L, Sharp SM, Bronner KK. Evaluating the efficiency of california providers in caring for patients with chronic illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W5–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hundley WG, Hamilton CA, Thomas MS, Herrington DM, Salido TB, Kitzman DW, Little WC, Link KM. Utility of fast cine magnetic resonance imaging and display for the detection of myocardial ischemia in patients not well suited for second harmonic stress echocardiography. Circulation. 1999;100:1697–702. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.16.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez MA, Anderson JL, Karagounis LA, Muhlestein JB, Mooers FB. An emergency department-based protocol for rapidly ruling out myocardial ischemia reduces hospital time and expense: results of a randomized study (ROMIO) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:25–33. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.