Abstract

Autophagy is a cellular survival pathway that recycles intracellular components to compensate for nutrient depletion and ensures the appropriate degradation of organelles. Mitochondrial number and health are regulated by mitophagy, a process by which excessive or damaged mitochondria are subjected to autophagic degradation. Autophagy is thus a key determinant for mitochondrial health and proper cell function. Mitophagic malfunction has been recently proposed to contribute to progressive neuronal loss in Parkinson disease. In addition to autophagy's significance in mitochondrial integrity, several lines of evidence suggest that mitochondria can also substantially influence the autophagic process. The mitochondria's ability to influence and be influenced by autophagy places both elements (mitochondria and autophagy) in a unique position where defects in one or the other system could increase the risk to various metabolic and autophagic related diseases.

Key words: autophagy, mitochondria, fission, fusion, apoptosis

Introduction

Autophagy is a cellular degradation system that is highly conserved among different eukaryotic species. Since the discovery of this pathway over 40 years ago, the identification of autophagy-regulating proteins (ATG) has tremendously increased our understanding of how autophagy functions.1,2 The orchestrated activation of the pro-autophagic Beclin1/PI3K complex and recruitment of ATG proteins induces the formation of autophagosomes. These double membranous vesicles sequester and degrade cytoplasmic materials. Among the autophagosomal substrates are cytosolic proteins, ribosomes and organelles (such as mitochondria and the ER) as well as bacteria and viruses.3 The enormous variety of substrates explains the close link between autophagy defects and diverse human diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. Seminal studies by Youle and colleagues identified the Parkinson disease-associated proteins Pink1 and Parkin as mediators of the selective degradation of dysfunctional mitochondria by autophagy (termed mitophagy).4 Disease-associated Parkin mutants caused loss of mitophagy upon mitochondrial damage,5,6 suggesting that the accumulation of damaged mitochondria could contribute to the mechanism of Parkinson disease.

The selective degradation of mitochondria by autophagy controls mitochondrial number and health. Besides being a substrate for autophagy, accumulating evidence indicates that mitochondria themselves can influence the autophagic process in several ways. To date, mitochondria have been linked to virtually every step of autophagy, including autophagosomal biogenesis and autophagic flux.7–9 In this short review, we summarize the possible means by which mitochondria and autophagy crosstalk, with an emphasis on the mitochondrial control of autophagy in mammalian cells. The strong interconnection between the mitochondrial and autophagic systems could potentiate the contribution of both systems for neurodegenerative, inflammatory and cancer-related diseases.

Mitochondria: A Dynamic Organelle

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles, with morphologies ranging from small roundish elements to larger interconnected networks. Mitochondrial architecture is not random, rather the opposing processes of fission and fusion specifically determine mitochondrial shape. On the molecular level, mitochondrial morphology is controlled through a family of dynamin-related proteins. Mitofusin 1 and 2 (Mfn1, Mfn2) and optic atrophic protein 1 (Opa1) fuse mitochondria,10 while fission is mainly regulated by the Dynamin-related protein1 (Drp1) and mitochondrial fission factor (Mff).11,12

The dynamic nature of mitochondria allows the adjustment of mitochondrial morphologies to specific cellular processes. For example, before cells enter the energy-costly DNA replication phase (S phase) mitochondria become hyperfused and increase their ATP production.13 Different cellular pathways can regulate the activity of mitochondria-shaping proteins and adapt mitochondrial architecture to the cell's state.14 Our best understanding of this regulation relates to Drp1 activity. Multiple posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation, sumoylation and ubiquitination events, regulate Drp1 activity and thus mitochondrial division.11,14 Mitochondrial shape is also determined through the activity of fusion proteins. The E3 ligase March5 has been identified to regulate fusion through targeting of Mfn1 and/or Mfn2.15,16 In addition, fusion is determined through mitochondrial membrane potential, as the activity of the inner membrane fusion protein Opa1 is voltage-dependent.17–20

The specific control of mitochondrial morphology has a significant impact on mitochondrial function and homeostasis. Mitochondrial fusion was suggested as a route for the rapid exchange of metabolites, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and membrane components,21–27 while fission is thought to facilitate the segregation of mtDNA and isolation of mitochondria from the network to allow their degradation.28–32 Through this, mitochondrial fission and fusion influences nearly all aspects of mitochondrial function, including respiration, calcium buffering and apoptosis.33–37

The dynamic nature of mitochondria is also essential for mitochondrial quality control. Healthy mitochondria go through continuous fission and fusion cycles, which are, in general, timely coupled. In this process, after fusion takes place, it is rapidly followed by a mitochondrial fission event. Mitochondria then spend the vast amount of time in a post-fission state, which they only leave by re-fusing into the mitochondrial network. As mitochondrial fusion is dependent on membrane potential (Δψ m), mitochondrial depolarization will retain mitochondria in a post-fissioned state.17–20,32 The continuous failure of damaged mitochondria to fuse back into the mitochondrial network eventually leads to mitochondrial elimination through autophagy.32 Mitochondrial dynamics thereby provides the cell with a powerful mechanism to regulate the number and overall health of mitochondria.

Mitochondria as an Autophagy Substrate

One link between autophagy and mitochondria is the selective elimination of excess or damaged mitochondria, a process called mitophagy. Mitochondria are degraded under a variety of different conditions, including basal mitochondrial quality control,32 mitochondrial dysfunction4,32 and during developmental processes, such as during the maturation of immature red blood cells.38–40 To date, considerable progress has been made in identifying mitophagic adaptors or the degradation of parental mitochondria after fertilization and understanding the overall importance of mitophagy for aging and neurodegenerative diseases.

Mitochondrial depolarization can occur naturally during mitochondrial fission or can be induced through cellular stress pathways, including apoptosis. Upon extensive damage, mitochondrial membranes can be permeabilized through distinct routes, and mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (MMP) constitutes one of the hallmarks of apoptotic or necrotic cell death.41 However, if the mitochondrial insult is not too severe and only a fraction of the mitochondrial pool is damaged, mitophagic degradation could rescue the cell and prevent cell death.

Damaged mitochondria can be recognized through the voltage-sensitive kinase Pink1. Under normal circumstances, Pink1 is continuously degraded on mitochondria, but upon loss of Δψm, Pink1 is stabilized on the outer mitochondrial membrane.42–44 The rapid accumulation of Pink1 on the mitochondrial surface facilitates recruitment of Parkin,45–49 an E3 ligase to mitochondria, where it ubiquitinates multiple mitochondrial proteins, including the fusion proteins Mfn1/2 and the VDAC1 protein.6,50–55 The accumulation of ubiquitin-modifications is thought to facilitate the recruitment of the autophagy adaptor p62, eventually leading to the autophagosomal degradation of the damaged mitochondrion.4–6,56 Mutations in the genes coding for both PINK1 and Parkin were identified in the early-onset forms of Parkinson disease. In cell culture models, disease-associated mutants of Pink1 and Parkin dramatically reduced the recruitment of Parkin to damaged mitochondria and their subsequent degradation.5,6,43,44,52

Another protein linked to mitophagy in mammalian cells is NIX. In immature red blood cells, NIX mediates the mitophagic removal of excess mitochondria.38,39,57 But the elimination of damaged mitochondria seems also be NIX-dependent in some cell lines.58 In addition to mitophagy-mediators, the loss of general autophagy regulators, like ATG5 or ATG7, also leads to significant accumulation of damaged mitochondria,59–65 further supporting the idea that autophagy plays an essential role in mitochondrial quality control to ensure the health of the mitochondrial pool.

Recent studies demonstrated that mitochondria are not only a downstream substrate of mitophagy, but that they are able to actively influence their own fate during starvation-induced autophagy. Two recent studies showed that during starvation, mitochondria react to the depletion of nutrients (especially nitrogen sources) with rapid and extensive mitochondrial tubulation.66,67 The formation of elongated mitochondrial networks appears to be dependent on the PKA-mediated inactivation of the fission protein Drp1, removing the counterbalancing force to fusion. Interestingly, these mitochondrial networks resulted in sustained mitochondrial ATP production, enhanced cellular survival66 and, most importantly, prevented the elimination of mitochondria.66,67 In contrast to this, fusion-incompetent mitochondria were heavily degraded during starvation. This suggests that mitochondrial morphology actively influences mitophagic responses.

The exact mechanism by which mitochondrial fusion prevents mitophagy is still unclear. The mitochondrial size alone could be a determining factor, as the loss of Drp1-activity also decreases mitophagy under basal conditions32 and upon external mitochondrial damage.4,53 Alternatively, changes in mitochondrial activity and/or recruitment of mitophagy-adaptors (like Parkin) could be causative for the decreased degradation of fused mitochondria.

Mitochondrial depolarization/fragmentation are two common prerequisites for mitophagy, and mitochondrial fusion can block mitophagy. This intimate link between mitochondrial shape and degradation suggests that both processes could also be coupled on the molecular level. Indeed, two different systems were identified that affect both mitophagy and mitochondrial shape. Parkin has been suggested to regulate mitochondrial fusion in addition to its well-established function as a mitophagy adaptor.4,68,69 A similar connection has been suggested for the autophagy-regulating proteins ATG12 and ATG3. During the induction of autophagy, ATG12 gets covalently linked to ATG5, thus driving the expansion and formation of the autophagosome. A recent study by Debnath and colleagues identified ATG3 as a further acceptor for ATG12.70 Lack of the covalent ATG12/3 complex led to mitochondrial fragmentation and loss of mitophagy, partially mimicking the effects of Parkin depletion in mammalian cells. Even though mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy are linked by several means, it will be important to understand which processes/proteins directly affect mitochondrial dynamics and which effects on mitochondrial shape are only secondary to changes in mitophagy and/or the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria.

Mitochondria as Autophagic Membrane Source

To date, the membrane origin(s) of autophagosomes remains under debate. Several organelles have been suggested to contribute lipids for the formation of autophagosomes, including the ER, the Golgi and plasma membrane.71–73 In a recent study, Hailey et al. added mitochondria to the growing list of potential autophagosomal membrane sources.8,74 Impressive imaging analysis revealed that during starvation, the membranes of autophagosomes and mitochondria are in continuity, allowing the transfer of a mitochondrial outer membrane marker (GFPcb5MitoTM) into nascent autophagosomes.

Although the question of how and from which organelle(s) autophagosomes originate is not fully clear, several lines of evidence support the role of mitochondria during autophagosomal biogenesis under starvation. In mammals, the autophagyregulating proteins Beclin1 and Bcl-2 not only localize to the ER and but also to mitochondria. Beclin1 is part of the pro-autophagic class III PI3K complex, which is implicated in the initiation of autophagosomal biogenesis.75–78 It was believed that the initiation of Beclin1-dependent autophagy is solely regulated on the level of the ER,79 but studies by Cecconi and colleagues identified Ambra1 (activating molecule in beclin1-regulated autophagy) as a potential contributor of Beclin1-dependent autophagosome formation from mitochondria.80 Under nutrient-rich conditions, Bcl-2 interacts both with AMBRA1 at the mitochondrial surface and Beclin1 at the ER to inhibit autophagy. But upon starvation, endogenous Ambra1 dissociates from Bcl-2, leading to an increased interaction between Ambra1 with Beclin1 on mitochondria and the ER. The mitochondrial Ambra1/Beclin1 complex could thus drive autophagsomal biogenesis from mitochondrial and ER membranes.

Another protein that could couple mitochondria to autophagosomal biogenesis is Endophilin B1, a membrane-shaping protein with pro-autophagic activity.81–84 Under normal circumstances, Endophilin B1 cycles between the cytosol and mitochondria and can be enriched on mitochondrial surfaces upon stress.85 On mitochondria, Endophilin B1 could activate the Beclin1-PI3K complex through binding of the Beclin1 adaptor UVRAG82 and drive autophagosomal biogenesis using mitochondrial membranes.

Several lines of evidence support mitochondria as a potential autophagosomal membrane source, which raises the question of why specifically starvation-induced autophagy (but not other types of autophagy) uses the mitochondrial membrane.8 The lipid requirements of autophagy could contribute to this selectivity. Phosphatidyl-ethanolamine, the lipid needed to covalently link ATG8 homologs to autophagosomal membranes, can be produced in two different locales, the ER and mitochondria.86 PE produced in the mitochondria is synthesized through decarboxylation of Phosphatidylserine, transferred from the ER into mitochondria. In the ER, the Kennedy pathway utilizes DAG and exogenous ethanolamine for the formation of PE. Nutrient depletion could limit the availability of DAG/ethanolamine (produced following growth factor engagement) and affect PE availability in the ER. This would make the mitochondrial membrane the primary site of PE production and, thereby, the site of autophagosomal biogenesis.

Unicellular organisms continuously adapt to fluctuating nutrient availability in their environment, but in mammalian tissues, nutrient levels are kept rather stable. Even though nutrient availability is tightly regulated, several processes that lead to the starvation of cells or tissues in mammals are known. Newborns proceed through starvation periods shortly after birth, during which autophagy is essential for survival.87 But starvation-induced autophagy also plays a role in cancer. In the microenvironment of tumors, where access to nutrients and oxygen is restricted, autophagy promotes tumor cell survival.88 In contrast to its pro-survival role in established tumors, autophagy suppresses tumor development. Dysfunctional mitochondria and protein aggregates are linked to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, activation of DNA damage and cell death.89–92 Degradation of these materials could protect cells against progressive cell damage, inflammation and thus cancer while promoting healthy aging.93–96

Therefore, mitochondria may be pivotal for autophagy in cancer, with changes in mitochondrial function regulating the autophagic process, resulting in promotion of tumor formation and/or preservation.

Mitochondria as Regulators of Autophagic Flux

Mitochondria are powerful metabolic organelles, producing precursors for lipid and amino acid synthesis, energy and signaling molecules, like reactive oxygen species (ROS). The central autophagy-regulating pathways, AMPK and mTOR, are controlled by energy levels.97–106 Loss of mitochondrial ATP production can thus induce autophagy in an mTOR/AMPK-dependent manner.100,107–109 Interestingly, mTOR and AMPK not only respond to mitochondrial output but also regulate mitochondrial function and biogenesis.110–112 For example, the pharmacological inhibition of mTOR rapidly affects mitochondrial metabolism and decreases oxidative phosphorylation.111 This clearly demonstrates the tight bidirectional connection between autophagy and mitochondria through signaling networks, which could play a central role for lifespan extension and age-related disorders.95

An additional mitochondrial product that influences autophagy is ROS. During nutrient starvation, an increase in H2O2levels is essential for autophagy induction.113 The autophagy protein ATG4 was identified as the basis for the redox sensitivity of autophagy. Throughout the formation of an autophagosome, the mammalian homologs of ATG8, LC3A or LC3B, are covalently attached to the nascent autophagosome, driving its expansion. The cysteine protease ATG4 can counteract the autophagosomal expansion through the removal of the ATG8 homologs from the autophagosomal membrane. ATG4 can be regulated by oxidation of a cysteine residue near its catalytic domain, which inhibits ATG4's cleavage activity and allows ATG8-mediated autophagosome expansion to proceed. Thus far, ATG4 is the only autophagy protein known to be regulated by ROS signaling, but other proteins might further contribute to the redox regulation of the autophagic process, including the autophagy master regulator mTOR itself.92,95,114,115

A recent study in yeast further expands the regulatory potential of mitochondria on the autophagic pathway. During specific starvation conditions, it was shown that mitochondrial integrity influences autophagic initiaion and/or autophagosomal degradation on the other side.7 The authors identified the mitochondrial membrane potential, but not ATP production, as regulator of autophagic flux. Interestingly, mitochondrial depolarization and loss of oxygen consumption have also been linked to reduced turnover of autophagosomes in mammalian cells (Rambold AS and Lippincott-Schwartz JL, unpublished results).9 Whereas mitochondrial dysfunction seemed to inhibit the recruitment of autophagy-initiation kinase ATG1/13 to the phagosomal initiation site in yeast, mitochondrial dysfunction has been linked with reduced lysosomal acidification in mammalian cells.7,9 The exact mechanism by which mitochondrial dysfunction influences autophagic flux still remains to be established in both systems.

Clearly, several mitochondrial outputs can regulate autophagy, either through targeting the autophagy machinery itself or autophagy regulating signaling pathways. Mitochondrial control of mTOR (through ATP and ROS)100,107–109,115 is of particular interest, as mTOR regulates a range of essential cellular functions, including protein translation and autophagy, and has been linked to aging in lower eukaryotes.116 Accumulating evidence suggests that mTOR also influences aging in mammals, and that the triad between mitochondria, mTOR and autophagy (all being able to regulate one another) might present an integral regulatory node during aging and thus age-related diseases.92,95,96,115,117

Mitochondria in the Autophagy: Apoptosis Crosstalk

Mitochondria play an essential role during apoptosis. Extensive cellular stress can lead to MMP, release of pro-apoptotic molecules, activation of caspases and, finally, apoptotic cell death. However, if MMP is limited to only a subset of mitochondria, this will result in the selective autophagosomal elimination of the depolarized mitochondria. This suggests efficient autophagic recognition of dysfunctional mitochondria could set a higher threshold for MMP to set an irreparable or deadly event in motion.

It is interesting to note the induction of autophagy and apoptosis are partially regulated by the same proteins. The antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 regulates autophagy and apoptosis through binding of the pro-autophagic protein Beclin1 and the pro-apoptotic protein Bax (and others).79,118 Cellular stress can lead to the release of both proteins. Nutrient depletion first leads to the release of Beclin1, causing the activation of PI3K and induction of autophagy.79,119,120 Upon extended nutrient deprivation the pro-apoptotic protein Bax is also released from Bcl-2,120 allowing it to induce apoptosis. The molecular coupling of both events, autophagy and apoptosis, could suggest that the cellular response to stress is determined by the severity and longevity of the insult. In an alternative to the stress-severity model, the different subcellular localizations of Bcl-2 (ER and mitochondria) might be integral to the fate switch between autophagy and apoptosis. While the Beclin1 sequestration seems to be mainly controlled through ER-localized Bcl-2,79 apoptosis could be regulated through Bcl-2 on mitochondria. Independent of the exact mechanism, it is clear that the health of mitochondria might determine the cellular outcome: autophagy or apoptosis. Thus, mitochondrial damage could overwhelm to pro-survival autophagy pathway and direct the cell toward release of pro-apoptotic Bax from Bcl-2 to induce cell death.

There are a number of additional mechanisms that couple autophagic demise to apoptotic onset involving mitochondria. The autophagy-regulating proteins Beclin1, the class III PI3K and ATG4D can all be cleaved by caspases upon which they translocate to mitochondria, where they acquire new functions and can amplify mitochondria-mediated apoptosis.121,122 In addition to this, caspase-dependent cleavage destroys the pro-autophagic function of Beclin1 and PI3K. Another protein that links apoptosis and autophagy is ATG5.123 Upon autophagy induction, ATG5 enables the extension of the autophagosome at its site of biogenesis. However, in response to high cellular stress levels, ATG5 can be cleaved by calpains. The ATG5-cleavage product translocates to mitochondria, where it binds Bcl-XL. In contrast to cleaved Beclin1, class III PI3K or ATG4D, calpain-processed ATG5 is able to induce apoptosis without the need for additional pro-apoptotic stimuli. These data exemplify the importance of mitochondrial integrity and their localized protein networks throughout the regulation of autophagy.

Conclusion

Mitochondria have been primarily connected to cellular ATP production and metabolism but have recently begun to take center stage in many other cellular processes. Mitochondria's connection to the autophagosomal system in particular has garnered much interest in recent years. To date, several lines of evidence support the notion that mitochondria are autophagic substrates and can also shape the autophagic response in several ways. The localization of many autophagic regulators on mitochondria, the integration of mitochondria in several signaling networks and their potential to modulate these pathways all suggest a powerful mitochondrial influence on autophagy. That said, we are still at the beginning of understanding the impact mitochondria have on autophagy. Delineating the multiple factors that underlie disorders that depend on autophagy, including neurodegenerative (like Parkinson disease) inflammatory diseases or cancer, and in particular, clarifying the tight link between cancer-associated changes in mitochondrial metabolism and dependence on autophagy during different steps of tumor formation and preservation will be invaluable for devising new ways to treat and prevent these diseases.

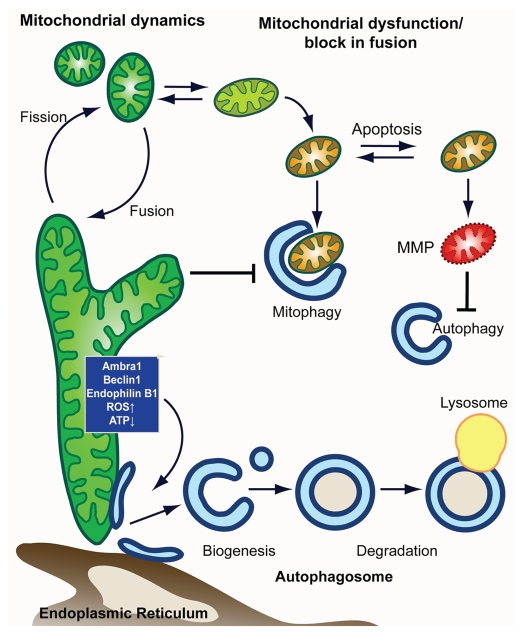

Figure 1.

Model for mitochondria-autophagy crosstalk. In this model, we depict the main intersection between in autophagy-mitochondrial crosstalk from the side of (1) autophagy and (2) mitochondria. (1) Autophagy shapes mitochondrial health and number through the selective degradation of mitochondria in a process termed mitophagy. Elimination of damaged mitochondria is facilitated by mitochondrial fission and promotes cell survival. Mitophagic malfunction leads to the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and makes the cell more susceptible to MMP and apoptosis. When cell death is induced, apoptotic executers inactivate pro-autophagic proteins, thus inhibiting autophagy. (2) Autophagic degradation of mitochondria is affected by mitochondrial shape/function, with heavily fused mitochondria being a poor substrate that evades autophagic degradation. Mitochondria, furthermore, are able to control autophagic induction and autophagsomal biogenesis from mitochondria (or other autohagosomal origins such as the er) through mitochondrial localized proteins and/or metabolic products (such as ROS and ATP).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Brenda Kostelecky and Tim Lammermann for critically reading the manuscript. We apologize for those studies we could not include in this review due to space constrains. A.S.R. was supported through a postdoctoral fellowship of the German Research Foundation (DFG).

References

- 1.Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:458–467. doi: 10.1038/nrm2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geisler S, Holmstrom KM, Skujat D, Fiesel FC, Rothfuss OC, Kahle PJ, et al. PINK1/Parkinmediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:119–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geisler S, Holmstrom KM, Treis A, Skujat D, Weber SS, Fiesel FC, et al. The PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is compromised by PD-associated mutations. Autophagy. 2010;6:871–878. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.13286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graef M, Nunnari J. Mitochondria regulate autophagy by conserved signalling pathways. EMBO J. 2011;30:2101–2114. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute-Krishnan P, Mitra K, Sougrat R, Kim PK, et al. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell. 2010;141:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Las G, Sereda S, Wikstrom JD, Twig G, Shirihai OS. Fatty acids suppress autophagic turnover in {beta}-cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42534–42544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.242412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoppins S, Nunnari J. The molecular mechanism of mitochondrial fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lackner LL, Nunnari JM. The molecular mechanism and cellular functions of mitochondrial division. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:1138–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otera H, Wang C, Cleland MM, Setoguchi K, Yokota S, Youle RJ, et al. Mff is an essential factor for mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1 during mitochondrial fission in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1141–1158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitra K, Wunder C, Roysam B, Lin G, Lippincott-Schwartz J. A hyperfused mitochondrial state achieved at G1-S regulates cyclin E buildup and entry into S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11960–11965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904875106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soubannier V, McBride HM. Positioning mitochondrial plasticity within cellular signaling cascades. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:154–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura N, Kimura Y, Tokuda M, Honda S, Hirose S. MARCH-V is a novel mitofusin 2- and Drp1binding protein able to change mitochondrial morphology. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:1019–1022. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park YY, Lee S, Karbowski M, Neutzner A, Youle RJ, Cho H. Loss of MARCH5 mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase induces cellular senescence through dynamin-related protein 1 and mitofusin 1. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:619–626. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duvezin-Caubet S, Jagasia R, Wagener J, Hofmann S, Trifunovic A, Hansson A, et al. Proteolytic processing of OPA1 links mitochondrial dysfunction to alterations in mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37972–37979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griparic L, Kanazawa T, van der Bliek AM. Regulation of the mitochondrial dynamin-like protein Opa1 by proteolytic cleavage. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:757–764. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishihara N, Fujita Y, Oka T, Mihara K. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology through proteolytic cleavage of OPA1. EMBO J. 2006;25:2966–2977. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song Z, Chen H, Fiket M, Alexander C, Chan DC. OPA1 processing controls mitochondrial fusion and is regulated by mRNA splicing, membrane potential and Yme1L. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:749–755. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busch KB, Bereiter-Hahn J, Wittig I, Schagger H, Jendrach M. Mitochondrial dynamics generate equal distribution but patchwork localization of respiratory Complex I. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23:509–520. doi: 10.1080/09687860600877292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jakobs S. High resolution imaging of live mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:561–575. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jakobs S, Schauss AC, Hell SW. Photoconversion of matrix targeted GFP enables analysis of continuity and intermixing of the mitochondrial lumen. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:194–200. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karbowski M, Arnoult D, Chen H, Chan DC, Smith CL, Youle RJ. Quantitation of mitochondrial dynamics by photolabeling of individual organelles shows that mitochondrial fusion is blocked during the Bax activation phase of apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:493–499. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakada K, Inoue K, Ono T, Isobe K, Ogura A, Goto YI, et al. Inter-mitochondrial complementation: Mitochondria-specific system preventing mice from expression of disease phenotypes by mutant mtDNA. Nat Med. 2001;7:934–940. doi: 10.1038/90976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono T, Isobe K, Nakada K, Hayashi JI. Human cells are protected from mitochondrial dysfunction by complementation of DNA products in fused mitochondria. Nat Genet. 2001;28:272–275. doi: 10.1038/90116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Twig G, Graf SA, Wikstrom JD, Mohamed H, Haigh SE, Elorza A, et al. Tagging and tracking individual networks within a complex mitochondrial web with photoactivatable GFP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:176–184. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00348.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barsoum MJ, Yuan H, Gerencser AA, Liot G, Kushnareva Y, Graber S, et al. Nitric oxide-induced mitochondrial fission is regulated by dynamin-related GTPases in neurons. EMBO J. 2006;25:3900–3911. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomes LC, Scorrano L. High levels of Fis1, a pro-fission mitochondrial protein, trigger autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:860–866. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.05.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malena A, Loro E, Di Re M, Holt IJ, Vergani L. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission favours mutant over wild-type mitochondrial DNA. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3407–3416. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suen DF, Narendra DP, Tanaka A, Manfredi G, Youle RJ. Parkin overexpression selects against a deleterious mtDNA mutation in heteroplasmic cybrid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11835–11840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914569107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Twig G, Elorza A, Molina AJ, Mohamed H, Wikstrom JD, Walzer G, et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:433–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amchenkova AA, Bakeeva LE, Chentsov YS, Skulachev VP, Zorov DB. Coupling membranes as energy-transmitting cables. I. Filamentous mitochondria in fibroblasts and mitochondrial clusters in cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:481–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aon MA, Cortassa S, O'Rourke B. Percolation and criticality in a mitochondrial network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4447–4452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307156101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frieden M, James D, Castelbou C, Danckaert A, Martinou JC, Demaurex N. Ca(2+) homeostasis during mitochondrial fragmentation and perinuclear clustering induced by hFis1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22704–22714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee YJ, Jeong SY, Karbowski M, Smith CL, Youle RJ. Roles of the mammalian mitochondrial fission and fusion mediators Fis1, Drp1 and Opa1 in apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5001–5011. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skulachev VP. Mitochondrial filaments and clusters as intracellular power-transmitting cables. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:23–29. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandoval H, Thiagarajan P, Dasgupta SK, Schumacher A, Prchal JT, Chen M, et al. Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nature. 2008;454:232–235. doi: 10.1038/nature07006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schweers RL, Zhang J, Randall MS, Loyd MR, Li W, Dorsey FC, et al. NIX is required for programmed mitochondrial clearance during reticulocyte maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19500–19505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708818104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato M, Sato K. Degradation of paternal mitochondria by fertilization-triggered autophagy in C. elegans embryos. Science. 2011 doi: 10.1126/science.1210333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Brenner C. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:99–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jin SM, Lazarou M, Wang C, Kane LA, Narendra DP, Youle RJ. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:933–942. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuda N, Sato S, Shiba K, Okatsu K, Saisho K, Gautier CA, et al. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:211–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Gautier CA, Shen J, et al. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:1000298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim PK, Hailey DW, Mullen RT, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Ubiquitin signals autophagic degradation of cytosolic proteins and peroxisomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20567–20574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810611105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sha D, Chin LS, Li L. Phosphorylation of parkin by Parkinson disease-linked kinase PINK1 activates parkin E3 ligase function and NFkappaB signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:352–363. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiba K, Arai T, Sato S, Kubo S, Ohba Y, Mizuno Y, et al. Parkin stabilizes PINK1 through direct interaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383:331–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Um JW, Stichel-Gunkel C, Lubbert H, Lee G, Chung KC. Molecular interaction between parkin and PINK1 in mammalian neuronal cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;40:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vives-Bauza C, Zhou C, Huang Y, Cui M, de Vries RL, Kim J, et al. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan NC, Salazar AM, Pham AH, Sweredoski MJ, Kolawa NJ, Graham RL, et al. Broad activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by Parkin is critical for mitophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1726–1737. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gegg ME, Cooper JM, Chau KY, Rojo M, Schapira AH, Taanman JW. Mitofusin 1 and mitofusin 2 are ubiquitinated in a PINK1/parkin-dependent manner upon induction of mitophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4861–4870. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JY, Nagano Y, Taylor JP, Lim KL, Yao TP. Disease-causing mutations in parkin impair mitochondrial ubiquitination, aggregation and HDAC6dependent mitophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:671–679. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201001039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanaka A, Cleland MM, Xu S, Narendra DP, Suen DF, Karbowski M, et al. Proteasome and p97 mediate mitophagy and degradation of mitofusins induced by Parkin. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1367–1380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ziviani E, Tao RN, Whitworth AJ. Drosophila parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates mitofusin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5018–5023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913485107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ziviani E, Whitworth AJ. How could Parkin-mediated ubiquitination of mitofusin promote mitophagy? Autophagy. 2010:6. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.5.12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okatsu K, Saisho K, Shimanuki M, Nakada K, Shitara H, Sou YS, et al. p62/SQSTM1 cooperates with Parkin for perinuclear clustering of depolarized mitochondria. Genes Cells. 2010;15:887–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mortensen M, Ferguson DJ, Simon AK. Mitochondrial clearance by autophagy in developing erythrocytes: clearly important, but just how much so? Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1901–1906. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.10.11603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding WX, Ni HM, Li M, Liao Y, Chen X, Stolz DB, et al. Nix is critical to two distinct phases of mitophagy, reactive oxygen species-mediated autophagy induction and Parkin-ubiquitin-p62-mediated mitochondrial priming. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27879–27890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ebato C, Uchida T, Arakawa M, Komatsu M, Ueno T, Komiya K, et al. Autophagy is important in islet homeostasis and compensatory increase of beta cell mass in response to high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2008;8:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Masiero E, Agatea L, Mammucari C, Blaauw B, Loro E, Komatsu M, et al. Autophagy is required to maintain muscle mass. Cell Metab. 2009;10:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mortensen M, Ferguson DJ, Edelmann M, Kessler B, Morten KJ, Komatsu M, et al. Loss of autophagy in erythroid cells leads to defective removal of mitochondria and severe anemia in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:832–837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913170107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakai A, Yamaguchi O, Takeda T, Higuchi Y, Hikoso S, Taniike M, et al. The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and in response to hemodynamic stress. Nat Med. 2007;13:619–624. doi: 10.1038/nm1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pua HH, Dzhagalov I, Chuck M, Mizushima N, He YW. A critical role for the autophagy gene Atg5 in T cell survival and proliferation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:25–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stephenson LM, Miller BC, Ng A, Eisenberg J, Zhao Z, Cadwell K, et al. Identification of Atg5-dependent transcriptional changes and increases in mitochondrial mass in Atg5-deficient T lymphocytes. Autophagy. 2009;5:625–635. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taneike M, Yamaguchi O, Nakai A, Hikoso S, Takeda T, Mizote I, et al. Inhibition of autophagy in the heart induces age-related cardiomyopathy. Autophagy. 2010:6. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.5.11947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gomes LC, Di Benedetto G, Scorrano L. During autophagy mitochondria elongate, are spared from degradation and sustain cell viability. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:589–598. doi: 10.1038/ncb2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rambold AS, Kostelecky B, Elia N, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Tubular network formation protects mitochondria from autophagosomal degradation during nutrient starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10190–10195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107402108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuroda Y, Mitsui T, Kunishige M, Shono M, Akaike M, Azuma H, et al. Parkin enhances mitochondrial biogenesis in proliferating cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:883–895. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lutz AK, Exner N, Fett ME, Schlehe JS, Kloos K, Lammermann K, et al. Loss of parkin or PINK1 function increases Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22938–22951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Radoshevich L, Murrow L, Chen N, Fernandez E, Roy S, Fung C, et al. ATG12 conjugation to ATG3 regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and cell death. Cell. 2010;142:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Axe EL, Walker SA, Manifava M, Chandra P, Roderick HL, Habermann A, et al. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:685–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ravikumar B, Moreau K, Jahreiss L, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Plasma membrane contributes to the formation of pre-autophagosomal structures. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:747–757. doi: 10.1038/ncb2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Young AR, Chan EY, Hu XW, Kochl R, Crawshaw SG, High S, et al. Starvation and ULK1-dependent cycling of mammalian Atg9 between the TGN and endosomes. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3888–3900. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rambold AS, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Starved cells use mitochondria for autophagosome biogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3633–3634. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.18.13170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Furuya N, Yu J, Byfield M, Pattingre S, Levine B. The evolutionarily conserved domain of Beclin 1 is required for Vps34 binding, autophagy and tumor suppressor function. Autophagy. 2005;1:46–52. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.1.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kihara A, Noda T, Ishihara N, Ohsumi Y. Two distinct Vps34 phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase complexes function in autophagy and carboxypeptidase Y sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:519–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–676. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tassa A, Roux MP, Attaix D, Bechet DM. Class III phosphoinositide-3-kinase-Beclin1 complex mediates the amino acid-dependent regulation of autophagy in C2C12 myotubes. Biochem J. 2003;376:577–586. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strappazzon F, Vietri-Rudan M, Campello S, Nazio F, Florenzano F, Fimia GM, et al. Mitochondrial BCL-2 inhibits AMBRA1-induced autophagy. EMBO J. 2011;30:1195–1208. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pierrat B, Simonen M, Cueto M, Mestan J, Ferrigno P, Heim J. SH3GLB a new endophilin-related protein family featuring an SH3 domain. Genomics. 2001;71:222–234. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Takahashi Y, Coppola D, Matsushita N, Cualing HD, Sun M, Sato Y, et al. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ncb1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Takahashi Y, Meyerkord CL, Wang HG. BARgaining membranes for autophagosome formation: Regulation of autophagy and tumorigenesis by Bif-1/Endophilin B1. Autophagy. 2008;4:121–124. doi: 10.4161/auto.5265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Takahashi Y, Meyerkord CL, Wang HG. Bif-1/endophilin B1: a candidate for crescent driving force in autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:947–955. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Karbowski M, Jeong SY, Youle RJ. Endophilin B1 is required for the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:1027–1039. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vance JE. Phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine in mammalian cells: two metabolically related aminophospholipids. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1377–1387. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700020-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Amaravadi RK, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Yin XM, Weiss WA, Takebe N, Timmer W, et al. Principles and current strategies for targeting autophagy for cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:654–666. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, Bray K, Anderson D, Chen G, et al. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mathew R, Karp CM, Beaudoin B, Vuong N, Chen G, Chen HY, et al. Autophagy suppresses tumorigenesis through elimination of p62. Cell. 2009;137:1062–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mathew R, Kongara S, Beaudoin B, Karp CM, Bray K, Degenhardt K, et al. Autophagy suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1367–1381. doi: 10.1101/gad.1545107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu JJ, Quijano C, Chen E, Liu H, Cao L, Fergusson MM, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress mediate the physiological impairment induced by the disruption of autophagy. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:425–437. doi: 10.18632/aging.100038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, Miyoshi H, Loh J, Lennerz JK, et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008;456:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature07416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakahara Y, Suzuki-Migishima R, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Morselli E, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Criollo A, Maiuri MC, Tavernarakis N, et al. Autophagy mediates pharmacological lifespan extension by spermidine and resveratrol. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:961–970. doi: 10.18632/aging.100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Raimundo N, Shadel GSA. “radical” mitochondrial view of autophagy-related pathology. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:354–356. doi: 10.18632/aging.100037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Egan D, Kim J, Shaw RJ, Guan KL. The autophagy initiating kinase ULK1 is regulated via opposing phosphorylation by AMPK and mTOR. Autophagy. 2011;7:643–644. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.6.15123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Inoki K, Zhu T. Guan KL, TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee JW, Park S, Takahashi Y, Wang HG. The association of AMPK with ULK1 regulates autophagy. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:15394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Löffler AS, Alers S, Dieterle AM, Keppeler H, Franz-Wachtel M, Kundu M, et al. Ulk1-mediated phosphorylation of AMPK constitutes a negative regulatory feedback loop. Autophagy. 2010;7:696–706. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shang L, Chen S, Du F, Li S, Zhao L, Wang X. Nutrient starvation elicits an acute autophagic response mediated by Ulk1 dephosphorylation and its subsequent dissociation from AMPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4788–4793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100844108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hardie DG. Sensing of energy and nutrients by AMP-activated protein kinase. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:891–896. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: a cellular energy sensor with a key role in metabolic disorders and in cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BST0390001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Desai BN, Myers BR, Schreiber SL. FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein associates with mitochondria and senses osmotic stress via mitochondrial dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4319–4324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261702698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schieke SM, Phillips D, McCoy JP, Jr, Aponte AM, Shen RF, Balaban RS, et al. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and oxidative capacity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27643–27652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Behrends C, Sowa ME, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature. 2010;466:68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cunningham JT, Rodgers JT, Arlow DH, Vazquez F, Mootha VK, Puigserver P. mTOR controls mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1-PGC-1alpha transcriptional complex. Nature. 2007;450:736–740. doi: 10.1038/nature06322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ramanathan A, Schreiber SL. Direct control of mitochondrial function by mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22229–22232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Reznick RM, Shulman GI. The role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mitochondrial biogenesis. J Physiol. 2006;574:33–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Scherz-Shouval R, Shvets E, Fass E, Shorer H, Gil L, Elazar Z. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J. 2007;26:1749–1760. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Filomeni G, Desideri E, Cardaci S, Rotilio G, Ciriolo MR. Under the ROS…thiol network is the principal suspect for autophagy commitment. Autophagy. 2010;6:999–1005. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.12754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sarbassov DD, Sabatini DM. Redox regulation of the nutrient-sensitive raptor-mTOR pathway and complex. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39505–39509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506096200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cuervo AM. Autophagy and aging: keeping that old broom working. Trends Genet. 2008;24:604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hands SL, Proud CG, Wyttenbach A. mTOR's role in aging: protein synthesis or autophagy? Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:586–597. doi: 10.18632/aging.100070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:571–580. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wei Y, Pattingre S, Sinha S, Bassik M, Levine B. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol Cell. 2008;30:678–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wei Y, Sinha S, Levine B. Dual role of JNK1mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 in autophagy and apoptosis regulation. Autophagy. 2008;4:949–951. doi: 10.4161/auto.6788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Betin VM, Lane JD. Caspase cleavage of Atg4D stimulates GABARAP-L1 processing and triggers mitochondrial targeting and apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2554–2566. doi: 10.1242/jcs.046250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wirawan E, Vande Walle L, Kersse K, Cornelis S, Claerhout S, Vanoverberghe I, et al. Caspase-mediated cleavage of Beclin-1 inactivates Beclin-1-induced autophagy and enhances apoptosis by promoting the release of proapoptotic factors from mitochondria. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:18. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yousefi S, Perozzo R, Schmid I, Ziemiecki A, Schaffner T, Scapozza L, et al. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1124–1132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]