Abstract

Background

Prior research has demonstrated the dimensionality of alcohol, nicotine and cannabis use disorders criteria. The purpose of this study was to examine the unidimensionality of DSM-IV cocaine, amphetamine and prescription drug abuse and dependence criteria and to determine the impact of elimination of the legal problems criterion on the information value of the aggregate criteria.

Methods

Factor analyses and Item Response Theory (IRT) analyses were used to explore the unidimensionality and psychometric properties of the illicit drug use criteria using a large representative sample of the U.S. population.

Results

All illicit drug abuse and dependence criteria formed unidimensional latent traits. For amphetamines, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizers and opioids, IRT models fit better for models without legal problems criterion than models with legal problems criterion and there were no differences in the information value of the IRT models with and without the legal problems criterion, supporting the elimination of that criterion.

Conclusion

Consistent with findings for alcohol, nicotine and cannabis, amphetamine, cocaine, sedative, tranquilizer and opioid abuse and dependence criteria reflect underlying unitary dimensions of severity. The legal problems criterion associated with each of these substance use disorders can be eliminated with no loss in informational value and an advantage of parsimony. Taken together, these findings support the changes to substance use disorder diagnoses recommended by the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 Substance and Related Disorders Workgroup.

Keywords: amphetamine use disorder, cocaine use disorder, prescription drug use disorder, DSM-5, item response theory

1. Introduction

One major change to substance use disorder diagnoses appearing in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5: American Psychiatric Association, 2011) will entail combining DSM-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV: American Psychiatric Association, 1994) abuse and dependence criteria to create one diagnosis for each substance assessed in the manual. Another change is the elimination of the legal problems of the DSM-IV abuse criteria as the result of its greater severity and much lower probability of endorsement relative to other abuse and dependence criteria.

Numerous studies using Item Response Theory (IRT) analyses have shown that DSM abuse and dependence criteria map well onto unidimensional continua of substance use disorder severity. IRT analysis defines the relationship between the observed responses to the criteria items and the underlying unobserved trait or construct (drug use disorder severity) and provides information of criterion functioning in terms of severity and discrimination. This result has been consistently robust across alcohol (Borges et al., 2009; Keys et al., 2010; Proudfoot et al., 2006; Saha et al., 2006, 2007; Shmulewitz et al., 2010), nicotine (McBride et al, 2010; Saha et al., 2010), cannabis (Bessemer et al., 2010; Compton et al, 2009; Martin et al., 2006; Tees son et al., 2002), amphetamine and cocaine (Gillespie et al., 2007; Langenbucher et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2009), hallucinogens and inhalant/solvent use (Kerridge et al., 2011) and illicit drug use disorders (Lynskey and Agrawal, 2007). Few studies, however, have examined the unidimensionality of amphetamine, cocaine and prescription drug use disorders in the general population. No study to our knowledge has explored the invariance of demographic characteristics on the latent construct nor directly examined the impact of eliminating the DSM-IV legal problems criterion associated with any substance except alcohol (Saha et al., 2006) and hallucinogens and inhalant/solvent use (Kerridge et al., 2011).

Among psychometric studies of cocaine use disorder criteria conducted in clinical settings (Laungenbucher et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2009), sample sizes were small (< 383) and in one of these studies (Wu et al., 2009) only dependence, but not abuse criteria were assessed. Another study focusing on the unidimensionality of both cocaine and amphetamines among Caucasian males participating in the Virginia Twin Registry, deliberately did not obtain information on abuse and dependence from at least 40% of the sample as the result of conditioning the assessment on restrictive definitions of substance use combined with requiring endorsement of at least one abuse criterion prior to assessment of dependence criteria (Gillespie et al., 2007). Yet, much less is known about the corresponding psychometric properties of sedative, tranquilizer and opioid use disorder criteria. Two studies, one focusing on adolescents (Wu et al, 2009) and the other on Caucasian Virginia Twins (Gillespie et al, 2007) found evidence to support the unidimensionality of sedatives and opioid abuse and dependence criteria, but the samples were limited and not generalizable to the full adult U.S. population. In another study conducted in the general population (Lynskey and Agrawal, 2007), discrimination and severity parameters of illicit drug abuse and dependence criteria were approximated from confirmatory factor analytic parameters and did not explore the impact of elimination of the legal problems criterion or invariance in factor scores.

In view of the methodological limitations of prior research, dearth of information on the impact of the elimination of the legal problems criteria from the substance use disorders, and strong evidence of the unidimensionality of abuse and dependence criteria for other substances including alcohol, cannabis and nicotine, as derived from Item Response Theory (IRT) analyses, the objectives of this study were to use IRT to: (1) determine whether amphetamine, cocaine, and prescription drugs (sedative, tranquilizer and opioid) abuse and dependence criteria measure unitary dimensions of severity in a large general population survey of the United States, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (Grant et al., 2003); (2) determine the impact of removing the legal problems criterion on IRT model fit and informational value of the amphetamine, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid use disorder diagnoses; and (3) examine differential criterion functioning as a means to assess bias in the diagnoses across important subgroups of the population such as sex, age and race-ethnicity.

2. Method

2.1 Sample

The 2001–2002 NESARC is a representative sample of the USA conducted by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and described elsewhere (Grant et al., 2003, 2004). The NESARC target population was the civilian non-institutionalized population residing in households and selected group quarters, 18 years and older. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 43,093 respondents, with a response rate of 81%. Blacks, Hispanics and young adults (ages 18–24) were oversampled with data adjusted for oversampling and household- and person-level non-response. The weighted data were then adjusted to represent the U.S. civilian population based on the 2000 census. For the current analyses, the samples were restricted to either lifetime users of cocaine (N=2,528), amphetamine (N=1,750), sedatives (N=1,609), tranquilizers (N=1,301) or opioids (N=1,815).

2.2 DSM-IV amphetamine, cocaine, sedative, tranquilizer and opioid abuse and dependence criteria

The Alcohol Use Disorders and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV (AUADIS-IV) (Grant et al., 2001) was designed to generate measures of amphetamine, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid abuse and dependence criteria. Following DSM-IV, the drug abuse criteria included: (1) use in hazardous situations; (2) failure to fulfill major role obligations at work/school/home; (3) legal problems related to use; or (4) social or interpersonal problems. DSM-IV dependence criteria included: (1) tolerance (either using much more of a specific drug to get the effect wanted or finding that the usual amount of a specific drug had less effect than it once did); (2) withdrawal; (3) using larger amounts for longer periods than intended; (4) persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use; (5) a great deal of time spent in activities to obtain drugs, or to recover from its effects; (6) giving up or reducing important social, occupational or recreational activities in favor of use; and (7) continued use despite knowledge of a physical or psychological problem caused or exacerbated by use. Consistent with the DSM-IV, the AUDADIS-IV withdrawal criterion for dependence was drug specific in terms of the nature of withdrawal symptoms required and the number of withdrawal criteria required for each drug examined in this study.

As reported in detail elsewhere, reliability and validity coefficients were good to excellent for cocaine, amphetamine, sedative, tranquilizer and opioid use disorder diagnoses (Chatterji et al., 1997; Cottler et al 1997; Grant et al., 1995, 2004; Hasin et al., 1997; Pull et al., 1997). Intra-class correlations of these drugs abuse and dependence criteria scales derived from a test-retest study of the general population (Grant et al., 1995, 2003) were excellent.

2.3 Statistical analysis

2.3.1 Factor analyses and unidimensionality

Factor analyses, conducted in a confirmatory factor analytic context using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2010), were used to assess the unidimensionality assumption underlying IRT analyses for amphetamine, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizers and opioid abuse and dependence criteria. Research has shown that the demonstration of unidimensionality substantially contributes to the stability of IRT parameter estimates and leads to a more accurate representation of the underlying data (Drasgow and Hulin, 1990; Hambleton, 1989). Factor analyses produce goodness of fit statistics and chi-square statistics. However, because the chi-square statistic is highly sensitive to large sample sizes, as in the case here, and may overstate the lack of fit of a structural model (Bollen, 1989), this test statistic was not used. Instead, a number of additional fit indices have been developed to address the problem associated with the chi-square statistic. Hu and Bentler (1999) provided a test of the “rules of thumb” cutoffs for the most commonly used fit indices. They advocated a two-index strategy to assess the adequacy of fit of structural models. Hu and Bentler (1999) suggest a cutoff of 0.95 or above on either the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI: Tucker and Lewis, 1973) or the comparative fit index (CFI: Bentler, 1990). A root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) “close to 0.06” also indicates good fit of a factor model.

2.3.2 IRT models

Two-parameter IRT models (Lord and Novick, 1968), were used to define the relationship between the observed responses to the criteria and the underlying unobserved latent trait or construct (illicit drug use disorder severity). This IRT model was generated using the marginal maximum likelihood estimates (Bock and Aitkin, 1981; Harwell et al., 1988) of two parameters: the a or discrimination parameter and b or threshold or severity parameter. The BILOG-MG statistical program was used for this purpose (Scientific Software International, 2003). The a parameter measures the ability of a criterion to discriminate people who are higher on the continuum from those who are lower on the continuum. The larger the a parameter, the greater the discrimination of a criterion. The b or threshold parameter measures the severity of a criterion; criteria with high thresholds are endorsed less frequently and are therefore considered “more severe”.

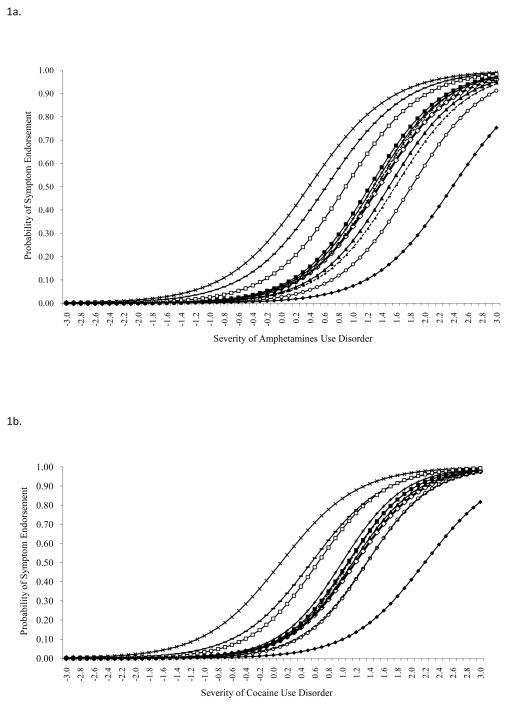

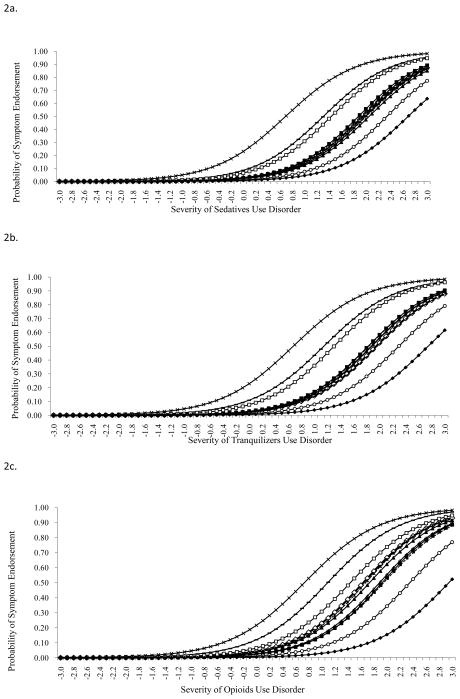

The a and b parameters are plotted graphically as criterion response curves (CRCs). In these plots, the b parameter represents the criterion’s location along the latent continuum (located on the horizontal axis). The b parameter (severity) is the point on the latent continuum where there is a 50% chance of the criterion being present. The b parameter shifts the CRC from left to right as the criterion becomes more severe. The a or discrimination parameter indicates how steep the slope of the CRC is at its steepest point. Comparisons between models with and without the legal problems criterion are conducted using the Bayesian Information Function (BIC). Lower values of the BIC indicate better fit of the model.

2.3.3 Aggregate Criteria Information Function (ACIF)

The IRT models of amphetamine, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizers and opioid use disorders with and without the legal problem criterion were examined with respect to information value. The aggregate criterion information function (ACIF) was estimated using BILOG-MG for each model (Scientific Software International, 2003). The ACIF graphically depicts the information value of the criteria as a collective or in the aggregate. The ACIF is the reciprocal error variance in an efficient estimate of the latent trait and measures the contribution of each criterion to the reduction of error of measurement. Statistical differences between the information values of ACIFs associated with models with and without the legal problems criterion were assessed by using the trapezoidal rule of integration to yield the total area under the curve (AUC) for each model’s ACIF. The trapezoidal rule is a numerical integration method used to approximate the integral or area under a curve. The rule evaluates the area between the curve and the y-axis by approximating the area with the area of trapezoids.

2.3.4 Differential Criterion Functioning (DCF)

To be clinically useful, amphetamine, cocaine, and prescription drug use criterion items should be shown to be invariant across important subgroups of the population defined in terms of sex, age and race-ethnicity. Although some researchers conduct statistical tests of differences between the a and b parameters associated with each criterion across subgroups to determine DCF, that is not an appropriate methodology when the DCF occurs in opposing directions (e.g., some criteria result in greater severity among men than women while other criteria demonstrate the opposite effect) (Cooke et al., 2001; Bolt et al., 2004). Whether DCF actually reflects invariance across subgroups can be determined if the observed criterion-level DCFs cancel out at the total test (scale) score level. To accomplish this, expected raw scores are plotted by the severity of the cocaine, amphetamine, sedative, tranquilizer and opioid use disorder continua for age, sex and race-ethnic groups – plots referred to as test response curves (TRCs). If the TRCs for subgroups (e.g., for men and women) do not substantially differ we can conclude that the significant criterion-level DCFs (if found) cancel out when considered at the total scale level and that for any latent trait value, men and women have identical expected raw scores. If, however, the TRCs do substantially differ by sex, age or race-ethnicity, criteria demonstrating DCF can be assumed to be biased, lacking invariance across important subgroups of the population.

3. Results

3.1 Prevalence and factor analyses

Lifetime prevalences of DSM-IV amphetamine abuse and dependence criteria ranged from 5.1% for the legal problems criterion to 38.2% for the quit/control criterion (Table 1). The one-factor solution was shown to be a good fit to the amphetamine criteria regardless of whether the model included (CFI=0.989; TLI=0.987; RMSEA=0.042) or excluded (CFI=0.989; TLI=0.986; RMSEA=0.047) the legal problems criterion.

Table 1.

Prevalence, Factor Loadings, IRT Parameters and Fit Statistics: Amphetamines

| Amphetamine Abuse (A) and Dependence (D) Criteria |

Prevalence (%) | Model With Legal Problems Criterion | Model Without Legal Problems Criterion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity estimate b (SE) | Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity, estimate b (SE) | ||

| Tolerance (D) | 16.69 | 0.842 | 1.96 (0.06) | 1.36 (0.05) | 0.844 | 1.97 (0.06) | 1.36 (0.05) |

| Withdrawal (D) | 18.00 | 0.887 | 2.01 (0.06) | 1.23 (0.05) | 0.889 | 2.02 (0.06) | 1.23 (0.05) |

| Larger/Longer (D) | 14.74 | 0.897 | 2.00 (0.06) | 1.50 (0.06) | 0.897 | 2.00 (0.06) | 1.50 (0.06) |

| Quit/Control (D) | 38.17 | 0.671 | 1.78 (0.05) | 0.38 (0.04) | 0.672 | 1.79 (0.05) | 0.38 (0.04) |

| Time spent (D) | 16.97 | 0.936 | 2.06 (0.06) | 1.32 (0.05) | 0.935 | 2.06 (0.06) | 1.32 (0.05) |

| Activities given up (D) | 10.80 | 0.881 | 1.98 (0.06) | 1.81 (0.06) | 0.883 | 1.99 (0.06) | 1.81 (0.06) |

| Physical/Psychological problems (D) | 18.11 | 0.891 | 2.00 (0.06) | 1.28 (0.05) | 0.894 | 2.02 (0.06) | 1.27 (0.05) |

| Neglect roles (A) | 12.80 | 0.856 | 1.97 (0.06) | 1.59 (0.06) | 0.851 | 1.96 (0.06) | 1.59 (0.06) |

| Hazardous use (A) | 32.80 | 0.697 | 1.82 (0.05) | 0.63 (0.04) | 0.691 | 1.82 (0.05) | 0.62 (0.04) |

| Social/Interpersonal problems (A) | 25.66 | 0.823 | 1.93 (0.05) | 0.90 (0.05) | 0.821 | 1.93 (0.05) | 0.89 (0.05) |

|

|

|||||||

| Legal problems (A) | 5.14 | 0.609 | 1.82 (0.05) | 2.39 (0.08) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.989 | 0.989 | |||||

| Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.987 | 0.986 | |||||

| Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.042 | 0.047 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | 13055.90 | 12478.11 | |||||

Table 2 shows that lifetime prevalences of DSM-IV cocaine abuse and dependence criteria ranged from 6.8% for the legal problems criterion to 46.2% for quit/control criterion. Factor analyses demonstrated a very good fit of the observed data underlying cocaine abuse and dependence criteria to the one-factor solution, for models with (CFI=0.994; TLI=0.993; RMSEA=0.049) and without (CFI=0.995; TLI=0.993; RMSEA=0.051) the legal problems criterion.

Table 2.

Prevalence, Factor Loadings, IRT Parameters and Fit Statistics: Cocaine

| Cocaine Abuse (A) and Dependence (D) Criteria |

Prevalence (%) | Model With Legal Problems Criterion | Model Without Legal Problems Criterion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity estimate b (SE) | Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity estimate b (SE) | ||

| Tolerance (D) | 19.38 | 0.868 | 2.09 (0.06) | 1.19 (0.04) | 0.870 | 2.10 (0.06) | 1.18 (0.04) |

| Withdrawal (D) | 21.48 | 0.917 | 2.21 (0.06) | 1.08 (0.04) | 0.917 | 2.22 (0.06) | 1.07 (0.04) |

| Larger/Longer (D) | 19.34 | 0.909 | 2.17 (0.06) | 1.15 (0.04) | 0.909 | 2.17 (0.06) | 1.15 (0.04) |

| Quit/Control (D) | 46.20 | 0.670 | 1.82 (0.05) | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.669 | 1.83 (0.05) | 0.11 (0.03) |

| Time spent (D) | 20.17 | 0.942 | 2.24 (0.07) | 1.10 (0.04) | 0.944 | 2.25 (0.07) | 1.09 (0.04) |

| Activities given up (D) | 16.02 | 0.921 | 2.19 (0.07) | 1.36 (0.04) | 0.922 | 2.20 (0.06) | 1.35 (0.04) |

| Physical/Psychological problems (D) | 22.63 | 0.933 | 2.24 (0.07) | 1.00 (0.04) | 0.935 | 2.26 (0.07) | 0.99 (0.04) |

| Neglect roles (A) | 15.94 | 0.891 | 2.13 (0.06) | 1.35 (0.04) | 0.888 | 2.12 (0.06) | 1.35 (0.04) |

| Hazardous use (A) | 33.39 | 0.749 | 1.90 (0.05) | 0.55 (0.03) | 0.747 | 1.91 (0.05) | 0.54 (0.03) |

| Social/Interpersonal problems (A) | 30.74 | 0.852 | 2.07 (0.06) | 0.65 (0.03) | 0.848 | 2.07 (0.06) | 0.64 (0.03) |

|

|

|||||||

| Legal problems (A) | 6.80 | 0.630 | 1.86 (0.05) | 2.20 (0.06) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.994 | 0.995 | |||||

| Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.993 | 0.993 | |||||

| Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.049 | 0.051 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | 19827.24 | 18859.32 | |||||

The prevalence of prescription drugs use disorder was lower as compared to cocaine and amphetamine. Lifetime prevalences of DSM-IV sedative abuse and dependence criteria ranged from 2.9% for the legal problems criterion to 29.9% for the quit/control criterion (Table 3). Factor analyses showed a good fit of a one-factor solution underlying sedative abuse and dependence criteria for models with (CFI=0.971; TLI=0.964; RMSEA=0.045) and without (CFI=0.971; TLI=0.962; RMSEA=0.049) the legal problems criterion, along with very strong factor loadings (0.646–0.900).

Table 3.

Prevalence, Factor Loadings, IRT Parameters and Fit Statistics: Sedatives

| Sedative Abuse (A) and Dependence (D) Criteria |

Prevalence (%) | Model With Legal Problems Criterion | Model Without Legal Problems Criterion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity estimate b (SE) | Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity estimate b (SE) | ||

| Tolerance (D) | 8.64 | 0.829 | 1.84 (0.05) | 1.96 (0.07) | 0.832 | 1.85 (0.05) | 1.95 (0.07) |

| Withdrawal (D) | 9.26 | 0.875 | 1.89 (0.06) | 1.88 (0.07) | 0.879 | 1.89 (0.05) | 1.88 (0.07) |

| Larger/Longer (D) | 8.33 | 0.823 | 1.84 (0.05) | 2.05 (0.08) | 0.827 | 1.84 (0.05) | 2.05 (0.07) |

| Quit/Control (D) | 29.89 | 0.646 | 1.74 (0.05) | 0.69 (0.05) | 0.650 | 1.75 (0.05) | 0.69 (0.07) |

| Time spent (D) | 9.01 | 0.900 | 1.90 (0.06) | 1.94 (0.08) | 0.903 | 1.90 (0.05) | 1.93 (0.07) |

| Activities given up (D) | 5.22 | 0.866 | 1.87 (0.06) | 2.34 (0.09) | 0.865 | 1.87 (0.05) | 2.35 (0.07) |

| Physical/Psychological problems (D) | 8.08 | 0.893 | 1.88 (0.06) | 1.99 (0.08) | 0.897 | 1.88 (0.05) | 1.99 (0.07) |

| Neglect roles (A) | 7.83 | 0.843 | 1.86 (0.05) | 2.00 (0.07) | 0.841 | 1.85 (0.05) | 2.01 (0.07) |

| Hazardous use (A) | 16.22 | 0.745 | 1.81 (0.05) | 1.31 (0.06) | 0.732 | 1.80 (0.05) | 1.31 (0.07) |

| Social/Interpersonal problems (A) | 13.67 | 0.813 | 1.85 (0.05) | 1.44 (0.06) | 0.802 | 1.84 (0.05) | 1.44 (0.07) |

|

|

|||||||

| Legal problems (A) | 2.92 | 0.688 | 1.80 (0.05) | 2.69 (0.10) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.971 | 0.971 | |||||

| Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.964 | 0.962 | |||||

| Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.045 | 0.049 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | 8959.27 | 8602.35 | |||||

Similar to sedatives, the lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV tranquilizer abuse and dependence criteria ranged from 2.8% for the legal problems criterion to 30.8% for the quit/control criterion (Table 4). A one-factor analytic solution fit the underlying data well for models with (CFI=0.981; TLI=0.976; RMSEA=0.042) and without (CFI=0.981; TLI=0.976; RMSEA=0.047) the legal problems criterion, along with strong factor loadings (0.673–0.924).

Table 4.

Prevalence, Factor Loadings, IRT Parameters and Fit Statistics: Tranquilizers

| Tranquilizer Abuse (A) and Dependence (D) Criteria |

Prevalence (%) | Model With Legal Problems Criterion | Model Without Legal Problems Criterion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity estimate b (SE) | Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity estimate b (SE) | ||

| Tolerance (D) | 8.99 | 0.862 | 1.90 (0.06) | 1.95 (0.08) | 0.863 | 1.90 (0.05) | 1.95 (0.08) |

| Withdrawal (D) | 10.22 | 0.878 | 1.91 (0.06) | 1.83 (0.08) | 0.881 | 1.92 (0.06) | 1.82 (0.08) |

| Larger/Longer (D) | 9.68 | 0.894 | 1.92 (0.06) | 1.87 (0.08) | 0.893 | 1.92 (0.06) | 1.87 (0.08) |

| Quit/Control (D) | 30.75 | 0.682 | 1.80 (0.05) | 0.68 (0.05) | 0.673 | 1.80 (0.05) | 0.68 (0.05) |

| Time spent (D) | 9.76 | 0.923 | 1.94 (0.06) | 1.84 (0.08) | 0.924 | 1.94 (0.06) | 1.83 (0.08) |

| Activities given up (D) | 5.92 | 0.867 | 1.89 (0.06) | 2.30 (0.09) | 0.868 | 1.89 (0.06) | 2.30 (0.09) |

| Physical/Psychological problems (D) | 9.53 | 0.900 | 1.92 (0.06) | 1.88 (0.08) | 0.904 | 1.93 (0.06) | 1.88 (0.08) |

| Neglect roles (A) | 8.22 | 0.894 | 1.91 (0.06) | 1.96 (0.08) | 0.895 | 1.91 (0.06) | 1.96 (0.08) |

| Hazardous use (A) | 19.83 | 0.741 | 1.83 (0.05) | 1.15 (0.06) | 0.736 | 1.83 (0.05) | 1.14 (0.06) |

| Social/Interpersonal problems (A) | 15.99 | 0.870 | 1.91 (0.06) | 1.30 (0.06) | 0.867 | 1.91 (0.06) | 1.30 (0.06) |

|

|

|||||||

| Legal problems (A) | 2.77 | 0.712 | 1.84 (0.05) | 2.75 (0.11) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.981 | 0.981 | |||||

| Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.976 | 0.976 | |||||

| Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.042 | 0.047 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | 7328.88 | 7063.27 | |||||

Table 5 shows that lifetime prevalences of DSM-IV opioid abuse and dependence criteria ranged from 2.3 % for the legal problems criterion to 28.3 % for the quit/control criterion. Results of the factor analyses showed a good fit to the one-factor solutions for the opioid models with (CFI=0.986; TLI=0.983; RMSEA=0.031) and without (CFI=0.987; TLI=0.983; RMSEA=0.035) the legal problems criterion. Factor loadings were high (0.586–0.912) for each model.

Table 5.

Prevalence, Factor Loadings, IRT Parameters and Fit Statistics: Opioids

| Opioid Abuse (A) and Dependence (D) Criteria |

Prevalence (%) | Model With Legal Problems Criterion | Model Without Legal Problems Criterion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity estimate b (SE) | Factor Loadings | Discrimination estimate a (SE) | Severity estimate b (SE) | ||

| Tolerance (D) | 12.07 | 0.867 | 1.90 (0.05) | 1.64 (0.06) | 0.868 | 1.90 (0.05) | 1.64 (0.06) |

| Withdrawal (D) | 8.43 | 0.912 | 1.93 (0.06) | 1.93 (0.07) | 0.912 | 1.93 (0.06) | 1.93 (0.07) |

| Larger/Longer (D) | 10.80 | 0.833 | 1.88 (0.05) | 1.73 (0.06) | 0.833 | 1.89 (0.05) | 1.73 (0.06) |

| Quit/Control (D) | 28.32 | 0.666 | 1.75 (0.05) | 0.74 (0.04) | 0.669 | 1.76 (0.05) | 0.73 (0.04) |

| Time spent (D) | 10.96 | 0.909 | 1.94 (0.06) | 1.67 (0.06) | 0.911 | 1.95 (0.06) | 1.67 (0.06) |

| Activities given up (D) | 5.34 | 0.799 | 1.85 (0.05) | 2.35 (0.08) | 0.797 | 1.85 (0.05) | 2.35 (0.08) |

| Physical/Psychological problems (D) | 8.87 | 0.883 | 1.92 (0.06) | 1.89 (0.07) | 0.885 | 1.92 (0.06) | 1.89 (0.07) |

| Neglect roles (A) | 7.66 | 0.831 | 1.88 (0.05) | 1.95 (0.07) | 0.829 | 1.88 (0.05) | 1.95 (0.07) |

| Hazardous use (A) | 19.78 | 0.739 | 1.82 (0.05) | 1.09 (0.05) | 0.737 | 1.82 (0.05) | 1.09 (0.05) |

| Social/Interpersonal problems (A) | 14.21 | 0.782 | 1.85 (0.05) | 1.44 (0.06) | 0.776 | 1.84 (0.05) | 1.44 (0.05) |

|

|

|||||||

| Legal problems (A) | 2.26 | 0.586 | 1.79(0.05) | 2.95 (0.11) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.986 | 0.987 | |||||

| Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.983 | 0.983 | |||||

| Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) | 0.031 | 0.035 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | 10672.01 | 10330.94 | |||||

For all illicit drugs, lifetime prevalence is lowest for legal problems criterion and highest for quit/control criterion.

3.2 Item Response Theory (IRT) analyses

Results of the IRT analyses are shown in Tables 1–5 for amphetamine, cocaine, sedative, tranquilizer and opioid abuse and dependence criteria, respectively, with the corresponding CRCs depicted in Figures 1a and 1b and 2a, 2b and 2c for models with the legal problems criterion. With respect to amphetamine, the legal problems criterion was by far the most severe (b=2.39). In both models, the quit/control, hazardous use and social/interpersonal problems criteria were the least severe, b=0.38, 0.63 and 0.90, respectively. Discrimination across criteria for both models was much less variable, ranging from 1.78 to 2.06. Corresponding results for cocaine mirrored those observed for amphetamine. Models without the legal problems criterion were a much better fit to the observed data than those that included the legal problems criterion for amphetamines (BICs=12478.11 vs. 13055.90) and cocaine (BICs=18859.32 vs. 19827.24).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Criterion Response Curves: Amphetamines

Tolerance

Tolerance

Withdrawal

Withdrawal

Larger/longer

Larger/longer

Quit/control

Quit/control

Time spent

Time spent

Activities given up

Activities given up

Physical/psychological

Physical/psychological

Neglect roles

Neglect roles

Hazardous use

Hazardous use

Social/interpersonal

Social/interpersonal

Legal Problems

Legal Problems

Figure 1b. Criterion Response Curves: Cocaine

Tolerance

Tolerance

Withdrawal

Withdrawal

Larger/longer

Larger/longer

Quit/control

Quit/control

Time spent

Time spent

Activities given up

Activities given up

Physical/psychological

Physical/psychological

Neglect roles

Neglect roles

Hazardous use

Hazardous use

Social/interpersonal

Social/interpersonal

Legal Problems

Legal Problems

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Criterion Response Curves: Sedatives

Tolerance

Tolerance

Withdrawal

Withdrawal

Larger/longer

Larger/longer

Quit/control

Quit/control

Time spent

Time spent

Activities given up

Activities given up

Physical/psychological

Physical/psychological

Neglect roles

Neglect roles

Hazardous use

Hazardous use

Social/interpersonal

Social/interpersonal

Legal Problems

Legal Problems

Figure 2b. Criterion Response Curves: Tranquilizers

Tolerance

Tolerance

Withdrawal

Withdrawal

Larger/longer

Larger/longer

Quit/control

Quit/control

Time spent

Time spent

Activities given up

Activities given up

Physical/psychological

Physical/psychological

Neglect roles

Neglect roles

Hazardous use

Hazardous use

Social/interpersonal

Social/interpersonal

Legal Problems

Legal Problems

Figure 2c. Criterion Response Curves: Opioids

Tolerance

Tolerance

Withdrawal

Withdrawal

Larger/longer

Larger/longer

Quit/control

Quit/control

Time spent

Time spent

Activities given up

Activities given up

Physical/psychological

Physical/psychological

Neglect roles

Neglect roles

Hazardous use

Hazardous use

Social/interpersonal

Social/interpersonal

Legal Problems

Legal Problems

For sedatives, IRT analyses indicated that the legal problems criterion was the most severe (b=2.69) in the model that included that criterion, while the activities given up, larger amounts/longer use and neglect roles criteria were the most severe (b=2.35, 2.05, 2.01) in the model that excluded the legal problems criterion (Table 3, bFigure 2a). The least severe criterion in both models was the quit/control criterion (=0.69, 0.69). Discrimination estimates were remarkably similar across sedative abuse and dependence criteria for both models (a=1.80–1.90). Model fit was better for the model without the legal problems criterion (BIC=8602.35) relative to the model with the legal problems criterion (BIC=8959.27).

The legal problems criterion was also shown to be the most severe (b=2.75) in the IRT tranquilizer model that included this criterion (Table 4, bFigure 2b), while the activities given up, neglect roles and tolerance criteria were the most severe (=2.30, 1.96, 1.95) in the model that excluded the legal problems criterion. Consistent with the results for sedatives, the least severe criterion in both tranquilizer models was quit/control (b=0.68, 0.68). Discrimination values associated with abuse and dependence criteria in each model were remarkably similar (a=1.80–1.94). Model fit was much better for the model that excluded the legal problems criterion (BIC=7063.27) relative to the model that included that criterion (BIC=7328.88).

The legal problems criterion was the most severe (b=2.95) and the quit/control criterion was the least severe (b=0.74) in the opioid model that included the legal problems criterion (Table 5, bFigure 2c). For the model that did not include the legal problems criterion, the most severe (=2.35, 195) criteria were activities given up and neglect roles, while the quit/control criterion remained the least severe (b=0.73). Similar to the results associated with sedatives and tranquilizers, discrimination values did not vary substantially across opioid criteria (a=1.75–1.95) in either model. Model fit was best for the model without the legal problems criterion (BIC=10330.94) relative to the model that retained the legal problems criterion (BIC=10672.01).

3.3 Aggregate Criterion Information Function (ACIF)

The ACIFs for amphetamine, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid use disorders visually depicted a slight reduction in information from the models that included the legal problems criterion to the models that excluded that criterion, especially at the severe end of the continuum (figures not shown). However, the area under the curve (AUC) for models with and without the legal problems did not significantly differ for all substances studied here.

The area under the curve (AUC) for the amphetamine models with and without the legal problems criterion did not significantly differ [AUC=20.1; 95% CI (2.83, 37.43) vs. AUC=18.9; 95% CI (1.27, 36.43)]. Areas under the corresponding ACIF curves for the cocaine models also did not significantly differ [AUC=22.2; 95% CI (6.41, 38.0) vs. AUC=20.8; 95% CI (4.60, 36.96)]. Similarly, the AUC for models with and without the legal problems criterion did not statistically differ for sedatives [AUC=17.6; 95% CI (−6.36, 41.48) vs. AUC=16.4; 95% CI (−7.72, 40.53)], tranquilizers [AUC=18.3; 95% CI (−5.33, 41.88)] vs. [AUC=17.2; 95% CI (−6.62, 40.92)] and opioids [AUC=18.0; 95% CI (−5.16, 41.08) vs. AUC=17.1; 95% CI (−6.27, 40.36)].

3.4 Differential Criterion Functioning (DCF)

Test response curves (TRCs) for the amphetamine, cocaine, sedative, tranquilizer and opioid models with and without legal problems criterion were virtually identical and overlapping for men and women, for each age group and for each race-ethnic group, indicating a lack of evidence for DCF of the abuse and dependence criteria (Figures not shown). This indicates invariance of the criterion across important subgroups of the general population and lack of bias in the diagnoses.

4. Discussion

Similar to the results of the majority of research on alcohol (Borges et al., 2010; Keys et al., 2010; Saha et al., 2006; 2007), nicotine (McBride et al., 2010; Saha et al., 2010; Shmulewitz et al., 2010), cannabis (Compton et al., 2009; Teesson et al., 2002) and hallucinogens and inhalant/solvent use (Kerridge et al., 2011), both factor and IRT analyses demonstrated the utility of conceptualizing amphetamine, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid abuse and dependence criteria (with and without the legal problems criterion) along unidimensional latent traits of drug use disorder severity. Model fit was better in the models excluding the legal problems criterion with no significant decrement to the total information relative to the corresponding models that included the legal problems criterion. Moreover, there was an absence of differential criterion functioning suggesting invariance and reliability of the criteria across important subgroups of the population defined in terms of sex, age and race-ethnicity.

Although the results of this study of amphetamine, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid use disorders were consistent with results for other substances (i.e. alcohol, cannabis and other drugs) in terms of unidimensionality, there were both similarities and differences in the relative ranking of severity parameters of this study compared to other studies. The relative ordering of cocaine and amphetamine abuse and dependence with respect to both severity and discrimination were remarkably similar, a result, in part, potentially due to the similar pharmacological action of each of these drugs classes. However, the ordering of criteria on the basis of severity found in the present study differs from those of prior research. In the two prior studies conducted among treated samples (Laungenbucher et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2009) the cocaine withdrawal criterion was one of the most severe observed, while in this study it was associated with an intermediate level of severity relative to other criteria. Consistent with the results of this study, the twin study of Gillespie et al., (2007) found the cocaine legal problems criterion to be one of the most severe. These disparities may reflect the severity of cocaine use disorders found among treated samples in which withdrawal would be expected to be a much more severe criterion than in this general population study. The severity of the cocaine legal problems criterion found in this study, but not in clinical studies, may reflect, in part, the broader range of severity of cocaine use disorder typically found in epidemiological studies compared with clinical studies.

This study also found that the cocaine quit/control, the hazardous use and social/psychological problems criteria were among the least severe criteria. The study of Lynskey and Agrawal study (2007) that also used the NESARC found that item difficulty parameters for quit/control and hazardous use were smaller but the legal problems criteria was larger. In contrast, other studies found the physical/psychological (Laugenbucher et al., 2004), cut down (Wu et al., 2009), activities given up (Lynskey and Agrawal, 2007) and larger/longer (Gillespie et al., 2007) criteria were the least severe. These differences may be due in part to differences in samples, sociodemographic characteristics, and assessment instruments.

Unlike the disparate findings with regard to severity found for cocaine criteria, the relative severity of amphetamine abuse and dependence criteria observed in this study and prior studies (Gillespie et al., 2007; Lynskey and Agrawal, 2007) was very similar. Consistent with the results of the present study, the legal problems criterion was consistently shown to be among the most severe criteria while the hazardous use criterion was among the least severe criteria. Although prior research focusing on amphetamine severity included only general population samples, that may account, in part, for the consistency in the findings, a complete explanation for consistency in these findings is not clear.

Once the legal problems criterion was removed from the sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid use disorder models, the rank order of severity of criteria was quite similar across the three substances in this study. Criteria for activities given up and neglecting roles were the most severe and the quit/control criterion was least severe. Lynskey and Agrawal (2007) also found the quit/control criterion to be the least severe, but found the withdrawal criterion to be the most severe for both sedatives and tranquilizers. In contrast, Gillespie et al. (2007) found the neglect roles and physical/psychological problems criteria to be the most severe sedative use disorder criteria, whereas hazardous use was the least severe criterion. Similar to the findings from this study for opioid, Lynskey and Agrawal (2007) demonstrated that the activities given up criterion was the most severe, but they also identified the withdrawal criterion as equally severe. In contrast to the results of this study, Wu et al (2009) found the quit/control and larger/longer criteria to be the most severe opioid criteria while Gillespie et al (2007) identified the most severe criteria as quit/control and neglect roles. Consistent with the results of this study, Lynskey and Agrawal (2007) identified quit/control as the least severe criterion, but the most severe criteria in the Wu et al. (2009) and Gillespie et al. (2007) studies were tolerance and time spent and hazardous use, respectively.

In the present study, discrimination parameters were remarkably consistent across amphetamine, cocaine, sedative, tranquilizer and opioid use disorder criteria. In contrast, other studies found great variability in the discrimination estimates associated with substance disorder criteria. Differences found in discrimination parameters of sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid use disorder criteria (like the differences in severity parameters described above) are in part due to differences in the samples in which the studies were conducted.

The results, taken together for all substances examined in this study, suggest the pattern of a single dimension is consistent, but in different populations, using different instruments, the precise order of severity and discrimination parameters varies. The relative ranking of the criteria in terms of severity and discrimination may well change developmentally over time, accounting for differences between the present study conducted in a general population of adults and the study based on adolescents in the general population (Wu et al., 2009). The unique characteristics of the Gillespie et al. (2007) twin sample suggests that generalizability may have been a factor in the differences found in IRT parameter values. Variability in the results may also be due, in part, to differences in the nature, reliability and validity of the assessment instruments used, the subgroups of illicit drug users on which the analyses were based, and statistical methodology used to estimate the IRT parameters.

Although IRT analyses indicated good fit of all illicit drugs models (amphetamines, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizers and opioids) both with and without the legal problems criterion, model fit was much better for models without the legal problems criterion. More importantly, there was no significant loss of information when the legal problems criterion was removed from the models including this criterion. These results support the exclusion of the legal problems criterion from definitions of drug use disorders, thereby increasing the clinical utility and parsimony of the new DSM-5 definitions.

For clinicians, the results suggest a simplified approach to diagnosis in that all substance use disorders have a unidimensional structure. Furthermore, eliminating the legal problems criterion from the diagnosis is supported as it adds little additional information to what is known from the presence or absence of other criteria. This represents another possible simplification to diagnosis. Taken together, findings in this study support combining abuse and dependence criteria in DSM-5 and eliminating the legal problems criterion, thereby aligning the criteria for cocaine, amphetamine, sedatives, tranquilizers and opioid with those for other substance use disorders. Further, the absence of differential criterion functioning across sex, age and race-ethnic groups support the clinical utility of new diagnoses in terms of reliability of the criteria and invariance in the underlying trait or construct.

This study was the first to examine DCF for amphetamine, cocaine, sedative, tranquilizer and opioid use disorders across subgroups of the population defined by sex, age and race-ethnicity. All drug use disorder criteria demonstrated virtually no DCF, suggesting that little or no differences exist in the expression of these criteria among various subgroups of population. These findings support the invariance of criteria functioning across sex, age and race-ethnicity and absence of bias associated with drug use disorder criteria.

Limitations of the study include reliance on self-report and recall bias associated with lifetime measures of drug use and criteria. However, AUDADIS-IV measures of cocaine, amphetamine, sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid use and abuse and dependence criteria demonstrated good to excellent reliability and validity in several psychometric studies (Chatterji et al., 1997; Cotttler et al., 1997; Grant et al., 1995; Hasin et al., 1997; Pull et al., 1997). The NESARC sample also excluded several small segments of the U.S. population in which rates of illicit drugs use and disorders are high, for example, prisons and drug abuse treatment facilities. Study strengths are additionally noted and include the stringent quality control and excellent response rate (83%) of the NESARC, the application of state-of-the-art statistical methodology, including a novel method to test statistical differences in information values between models, testing the invariance across important subgroup and the use of a large representative sample of the U.S. population necessary to address limitations in the generalizability of prior research in this area.

In summary, this study found support for combining abuse and dependence criteria (without the legal problems criterion) for cocaine, amphetamines, sedatives, tranquilizers and opioids, a step towards standardizing the diagnostic criteria across all substances appearing in the DSM- 5. Evidence of the unidimensionality of the abuse and dependence criteria also provides the foundation for constructing dimensional scales of amphetamine, cocaine, sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid use disorder severity as a complement to dichotomous diagnoses. Future research is needed to examine other recommended changes to the DSM-IV criteria including the identification of appropriate cut point for the diagnosis and the assessment of unidimensionality of criteria with the adding of a new criterion for craving. The development of standardized diagnoses across substance use disorders with provisions for the measurement of severity promises to improve the diagnoses and treatment of cocaine, amphetamine, sedatives, tranquilizer and opioid use disorders.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) funded the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) with supplemental funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

One recommendation by the Editor of this Journal was to combine two separate manuscripts, one concerning amphetamines and cocaine and the other focusing on prescription drug use disorders. In view of this recommendation, this combined manuscript has two Co-First authors, Drs. Saha and Compton.

Footnotes

Contributors

Dr. Saha conducted statistical analyses. Drs. Saha and Compton wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Drs. Grant, Chou and Smith revised and commented on subsequent drafts of the manuscript. Drs. Saha, Smith, Chou, Huang and Mr. Pickering and Ms. Ruan collected the data and administered the study.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Draft Criteria. 5. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C: 2011. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:203–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock RD, Aitkin M. Marginal maximum likelihood estimation of item parameters: application of an EM algorithm. Psychometrika. 1981;46:443–445. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. Wiley; New York, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bolt DM, Hare RD, Vitale JE, Newman JP. A multigroup item response theory analysis of the Psychopathy Checklist-revised. Psychol Assess. 2004;16:155–168. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Ye Y, Bond J, Cherpital CJ, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swittkiewick G, Ribio-Stipec M. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders and alcohol consumption in a cross-naitonal perspective. Addiction. 2010;105:240–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breseler CL, Hasin DS. Cannabis dimensionality: dependence, abuse and consumption. Addict Behav. 2010;35:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterji S, Saunders JB, Vrasti R, Grant BF, Hasin D, Mager D. Reliability of the alcohol and drug modules of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-Alcohol/Drug-Revised (AUDADIS-ADR): an international comparison. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:171–185. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DJ, Kosser DS, Michie C. Psychopathy and ethnicity: structural, item and test generalizability of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) in Caucasian and African American participants. Psychol Assess. 2001;13:531–542. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Saha TD, Conway KP, Grant BF. The role of cannabis use within a dimensional approach to cannabis use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Grant BF, Blaine J, Mavreas V, Pull C, Hasin DS, Compton WM, Rubio-Stripec M, Mager D. Concordance of DSM-IV alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by AUDADISADR, CIDI and SCAN. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drasgow F, Hulin CL. Item response theory. In: Dunnette MD, Hough LM, editors. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2. Vol. 2. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1990. pp. 577–636. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie NA, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. Factor and item-response analysis DSM-IV criteria for abuse of and dependence on cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, sedatives, stimulants and opioids. Addiction. 2007;102:920–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule – DSM-IV Version. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2010. [Accessed January 9, 2010]. Available at http://www.niaaa.nih.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Moore TC, Shepard J, Kaplan K. Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2003. Source and accuracy statement. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton WM, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton RK. Principles and selected applications of item response theory. In: Linn RL, editor. Educational Measurement, American Council on Education. 3. Macmillan Publishing; New York, NY: 1989. pp. 147–200. [Google Scholar]

- Harwell MR, Baker FB, Zwarts M. Item parameter estimation via marginal maximum likelihood and an EM algorithm: a didactic. J Educ Stat. 1988;13:243–271. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McClooud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equat Model. 1999;26:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge BT, Saha TD, Smith S, Chou PS, Pickering RP, Huang B, Ruan JW, Pulay AJ. Dimensionality of hallucinogen and inhalant/solvent abuse and dependence criteria: implications for the diagnostic and statistical manual of mentaldisorders, 5th Ed. Addict Behav. 2011;36:912–918. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys KM, Krueger RF, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Alcohol craving and dimensionality of alcohol use disorders. Psych Med. 2010;12:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000053X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenbucher JW, Labouvie E, Martin CS, Sanjuan PM, Bavly L, Kirisci L, Chung T. An application of item response theory analysis to alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine criteria in DSM-IV. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:72–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord FM, Novick MR. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Agrawal A. Psychometric properties of DSM assessments of illicit drug abuse and dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Psychol Med. 2007;37:1345–1355. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride O, Strong DR, Kahler CW. Exploring the role of a nicotine quantity-frequency criterion in the classification of nicotine dependence and the stability of a nicotine dependence continuum overtime. Nic Tob Res. 2010;12:207–216. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Chung T, Langenbucher JW, Kirisci L. Item response theory analysis of diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders in adolescents: implications for DSM-V. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:807–814. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables (Version 6.0) Muthén and Muthén Inc; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot H, Baillie AJ, Teesson M. The structure of alcohol dependence in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pull CB, Saunders JB, Mavreas V, Cottler LB, Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blaine J, Mager D, Ustun BT. Concordance between ICD-10 alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by the AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN: results of a cross-national study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Stinson FS, Bridget BF. The role of alcohol consumption in future classifications of alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Compton WM, Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Grant BF. Dimensionality of DSM-IV nicotine dependence in a national sample: an item response theory application. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Toit M, editor. Scientific Software International. Item Response Theory (IRT) from SSI. Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shmulewitz D, Keyes K, Bessemer C, Ajaaronovich E, Aivadyan C, Spivak B, Hasin D. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders: results from Israel. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M, Lynskey M, Manor B, Baillie A. The structure of cannabis dependence in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Pan JJ, Blazer DG, Tai B, Brooner RK, Stitzer ML, Patkar AA, Blaine JD. The construct and measurement equivalence of cocaine and opioid dependences: a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]