Whilst pharmacogenetic research thrives1, genetic determinants of response to purely psychotherapeutic treatments remain unexplored. In a sample of children undergoing Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) for an anxiety disorder, we tested whether treatment response is associated with the serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5HTTLPR), previously shown to moderate environmental influences on depression. Children with the short-short genotype were significantly more likely to respond to CBT than those carrying a long allele.

There is considerable evidence of association between anxiety/depression and the 5HTTLPR, particularly in response to stress2. Moreover, the low expression S allele, typically associated with poorer outcomes following stress, is also associated with better outcomes under low stress and may reflect sensitivity to the environment3. We hypothesized that this allele would be associated with enhanced response to psychological therapies4.

We collected DNA from 584 anxiety-disordered children aged 6-13 years, undergoing manual-based CBT5 at research clinics in Sydney, Australia and Reading, UK. We focus on 359 children with 4 white European grandparents (entire sample findings similar; see Supplementary Information). Families provided data pre-treatment, post-treatment and at follow-up (usually 6-months, for detailed methods see Supplementary Information).

Parental DNA was obtained for 389 children (267 white), and parents self-rated depression, anxiety and stress6. Parents provided informed consent, children assent. Genomic DNA was extracted from buccal and blood samples using established procedures. The 5HTTLPR genotypes were in Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium. There was no significant difference in genotypic frequencies between cases and 459 white European psychiatrically well controls7 (χ22 = 0.40, p = .82).

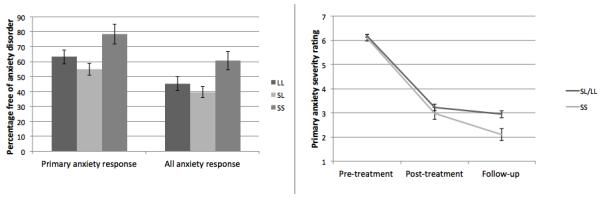

Treatment response was considered as the absence of the primary (“primary anxiety response”), or any (“all anxiety response”) anxiety disorder. As all analyses test the same core hypothesis, we did not correct for multiple testing. The 5HTTLPR was significantly associated with both “primary” and “all” anxiety response at follow-up (Figure 1i); a recessive model was indicated. Positive “primary” (“all”) anxiety response at follow-up was seen in 20.0% (18.8%) more children with the SS than the SL/LL genotypes; 78.4% vs. 58.4%, p < .01 (60.8% vs. 42.0%, p < .02). The influence of 5HTTLPR remained significant even after controlling for significant clinical predictors of treatment response (mood disorders, pre-treatment symptom severity and maternal psychopathology), and time (to follow-up), age, gender and treatment site. The odds ratios for 5HTTLPR-SS were .39, p = .02 (.44, p = .03) for “primary” (“all”) anxiety response. Furthermore, the 5HTTLPR also significantly predicted change in symptom severity from pre-treatment to follow-up (Figure 1ii) even after controlling for significant clinical covariates (β = −.17, p < .01). For full results see Supplementary Information.

Figure 1. Proportion of children free of (a) their primary anxiety disorder and (b) all anxiety disorders at follow-up by 5HTTLPR genotype.

Note. 1(i). There were significant associations at follow-up between both “primary anxiety response” and “all anxiety response” respectively, using either a genotypic (χ22 = 8.61, p = .01; χ22 = 6.60, p = .04) or recessive (χ21 = 7.03, p = <.008; χ21 = 5.88, p = .02) model. 1(ii) Children with the SS genotype showed significantly greater reduction in symptom severity from pre-treatment to follow-up (β = −.15, p < .01). At post-treatment the difference was not significant (β = −.03, p = .55).

This is the first study to explore the association between a genetic marker and response to a purely psychological treatment. One previous pilot study (N = 69) found an association between COMTval158met and CBT response in adult panic disorder, but many subjects were also medicated8. A naturalistic study (N = 111) of adult bulimia found that those with the 5HTTLPR S allele were less likely to respond to treatment, be it CBT, medication or both9. We found that in anxiety-disordered children, those with the 5HTTLPR SS genotype were 20% more likely to be disorder-free by follow-up than those with SL/LL genotypes. Whilst these findings hold true in the white subset and the entire dataset, the sample is relatively small and there is no independent replication so they must be considered preliminary. Furthermore, the association with 5HTTLPR was only seen at follow-up. The period between post-treatment and follow-up is typically characterised by continued improvement as the child applies the skills learnt10, thus it is possible that the genotype influences capacity for continued benefit from the intervention.

These findings are important both clinically and conceptually. First, our data suggest that “therapygenetics”, like pharmacogenetics1, may have the potential to inform treatment choices. Second, the possibility that the 5HTTLPR influences responsivity to psychological treatment4, is in keeping with the hypothesis that this marker reflects environmental sensitivity3. In conclusion, if replicated, these results may provide a tool that could help decide whether an individual is likely to benefit from standard CBT alone or whether enhanced treatment is required.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Supplementary information is available at Molecular Psychiatry’s website.

References

- 1.Keers R, Aitchison KJ. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2011;11:101–125. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 Jan 3; doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belsky J, Jonassaint C, Pluess M, Stanton M, Brummett B, Williams R. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:746–754. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uher R. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:1070–1078. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyneham HJ, Abbott MJ, Wignall A, Rapee RM. The Cool Kids Anxiety Treatment Programme. MUARU, Macquarie University; Sydney: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schosser A, Gaysina D, Cohen-Woods S, Chow PC, Martucci L, Craddock N, et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2010 Aug;15:844–849. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lonsdorf TB, Ruck C, Bergstrom J, Andersson G, Ohman A, Lindefors N, et al. Bmc Psychiatry. 2010 Nov;10:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steiger H, Joober R, Gauvin L, Bruce KR, Richardson J, Israel M, et al. J Clin Psychiatr. 2008;69:1565–1571. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James A, Soler A, Weatherall R. Cochrane review: Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2007. pp. 1248–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.