Abstract

Objective

Cervicogenic headache (CGH) is known to be mainly related with upper cervical problems. In this study, the effect of radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN) for lower cervical (C4-7) medial branches on CGH was evaluated.

Methods

Eleven patients with neck pain and headache, who were treated with lower cervical RFN due to supposed lower cervical zygapophysial joint pain without symptomatic intervertebral disc problem or stenosis, were enrolled in this study. CGH was diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria of the cervicogenic headache international study group. Visual analogue scale (VAS) score and degree of VAS improvement (VASi) (%) were checked for evaluation of the effect of lower cervical RFN on CGH.

Results

The VAS score at 6 months after RFN was 2.7±1.3, which were significantly decreased comparing to the VAS score before RFN, 8.1±1.1 (p<0.001). The VASi at 6 months after RFN was 63.8±17.1%. There was no serious complication.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that lower cervical disorders can play a role in the genesis of headache in addition to the upper cervical disorders or independently.

Keywords: Cervicogenic headache, Radiofrequency, Neurotomy, Medial branch

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 80% of cervical whiplash patients complained of headache31), which persist for 2 years in approximately 25% of the patients3). Even in headache patients without any cervical injury history, approximately 39% were reported to have neck pain30). This indicates that cervical disorders are closely related with headache, and a considerable number of the patients can possibly be diagnosed as cervicogenic headache (CGH).

Many different treatments have been applied for CGH, including medication, physiotherapy, nerve block, and radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN)25,26,37). The RFN for cervical medial branches has been recommended as a promising treatment method for CGH19,33,43). Although CGH is known to be mostly related with the upper cervical roots (C1-3) disorders8), there were also evidences showing the relationship between lower cervical disorders and CGH15,36). However, there was no study reporting directly on the effect of RFN for lower cervical (C4-7) medial branches on CGH.

In this study, we investigated the effect of lower cervical RFN on CGH in the patients who were treated by lower cervical RFN for lower cervical zygapophysial joint pain (CZJP).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Eleven CGH patients who underwent lower cervical RFN for treatment of CZJP during the past 3 years (July 2007-June 2009) were enrolled in this retrospective study. All the patients had neck pain with referred pain to shoulder and arm, and unilateral occipital headache, persisting for more than 3 months despite NSAID and proper physiotherapy. On the cervical MRI study, there werer no specific surgical conditions related to the symptoms. The original headache were precipitated by digital pressure at both the upper and lower cervical regions and the presumptive lower cervical facets. Candidates of RFN were selected when comparative local anesthetic blocks with 0.5 mL of 1% lidocaine and 0.5% bupivacaine for each medial branch showed a positive response; more than 90% pain relief and the duration of relief with bupivacaine should last at least 3 hours longer than that with lidocaine5).

Lower cervical radiofrequency neurotomy

We recommended lower cervical RFN when the patient did not want to additional procedures for headache. RFN was performed under biplane fluoroscope with a radiofrequency generator (Radionics RFG-3B, Radionics, Inc., Burlington, MA, USA) and SMK-C10 cannula with a 4 mm exposed tip (Radionics, Inc., Burlington, MA, USA) at C4-7 facets ipsilateral to the symptom side. The cannula was inserted obliquely trying to be parallel to the medial branches at the lateral margin of the articular pillar, and positioned at the center of it on lateral fluoroscopic view. Low voltage (0.5 V) sensory and motor stimulations were performed at 50 Hz and 2 Hz, respectively. At this point, a radiofrequency lesion was made at 90℃ for 60 seconds (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fluoroscopic images of cervical spine during radiofrequency facet rhizotomy at right C4-7 levels.

Evaluation of outcome

The pre- and post-RFN levels of headache were evaluated by visual analogue scale (VAS) score. The VAS score was measured at one day before RFN (pre-VAS), 7 days, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months after RFN (post-VAS). The degree of VAS improvement (VASi) (%) was calculated by comparing the difference between the pre- and post-VAS to the pre-VAS at the four time points after RFN. The VASi more than 50% at 6 months after RFN was considered a successful result, which is equal to the excellent or good result according to the Macnab criteria34).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by paired t-test and considered statistically significant when p<0.05. The values were presented as mean±SD.

RESULTS

Patients

The total number of neck pain patients without any symptomatic disc disorders or stenosis during the same period was 1872. Among the patients, 116 patients were diagnosed to have CZJP and underwent cervical RFN, 6.2% of the total number of neck pain patients. Twenty-eight CZJP patients confirmed to have CGH by comparative local anesthetic blocks, 1.5% (28/1872) and 24.1% (28/116) of total neck pain patients and CZJP patients, respectively. Of these 28 patients, 11 patients (39.3%), whose initial diagnosis was lower CZJP, experienced disappearing headache by comparative local anesthetic block at C4-7 levels. The 11 patients underwent RFN at C4-7 and were successfully followed up more than 6 months.

The mean age of the lower CZJP patients with CGH was 45.3±12.4 (26-69) years. There were 3 male and 8 female patients with a male to female ratio of 1 : 2.7. The mean symptom duration was 12.6±12.3 (3 to 36) months. The mean pre-VAS was 8.1±1.1. All the CZJP patients showed combined symptoms other than headache such as dizziness in 9, nausea in 4, ophthalmic pain in 4, blurred vision in 4, and tinnitus in 3 patients.

Outcome

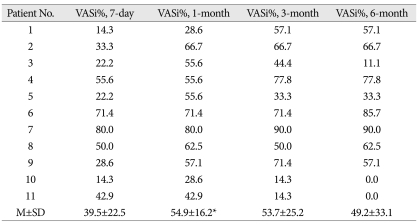

Post-RFN VAS scores for headache at 7 days, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months were 4.8±1.8, 3.5±1.0, 3.6±1.9, and 4.0±2.5, respectively, all of which were significantly decreased compared to pre-VAS score, 8.1±1.1 (p<0.001) (Table 1). The degrees of VASi at 7 days, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months after RFN were 39.5±22.5%, 54.9±16.2%, 53.7±25.2%, and 49.2±33.1%, respectively. The degree of VASi was relatively lower at 7 days (p<0.05), peak at 1 month, and then decreased slowly with time (Table 2). The degree of VASi at 6 months after RFN was more than 50% in 7 patients (63.6% of success rate).

Table 1.

List of patients including gender, age, and the changes of visual analogue scale (VAS) scores according to the time duration after radiofrequency neurotomy

*p<0.001, compared with the pre-VAS (paired t-test). pre-VAS : pre-operative VAS score, post-VAS : post-operative VAS score, M±SD : mean±standard deviation

Table 2.

Degrees of visual analogue scale (VAS) improvement and their changes according to the time duration after radiofrequency neurotomy

*p<0.05, compared with the degree of VASi at 7 days after radiofrequency neurotomy (paired t-test). VASi% : degree (%) of VAS score improvement comparing to the pre-VAS

There was no specific permanent complication. Most of the patients experienced pain at the needle insertion sites for several days after RFN. Sensory changes (hypoesthesia and/or paresthesia) at posterolateral neck and shoulder were noted in two patients for several weeks (3 and 4 weeks) and then disappeared completely.

DISCUSSION

CGH can be defined as a headache originating from a neck condition2,32,42). The use of the term CGH was controversial due to lack of consensus among physicians in the past17,25,32). Even there had been confusion regarding the use of terms such as greater occipital neuralgia12,22), third occipital neuralgia9,38), representing the same clinical condition as CGH. CGH was first introduced in 198342) and is currently being investigated mainly by the Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group (CHISG) and the International Headache Society (IHS). As a result, CGH can be diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria of the CHISG41) or IHS27). According to the diagnostic criteria of the CHISG41), CGH can be diagnosed with precipitation of headache by external pressure over the upper cervical or occipital region, positive response for comparative local anesthetic blocks, and unilaterality of headache without spreading across the midline. But, in this study, the headache related with lower cervical disorders in the CZJP patients was confirmed by comparative local anesthetic blocks at C4-7 levels.

The prevalence of CGH in the general population ranges from 0.4% to 2.5%37,40), and CGH was reported in approximately 1.5% to 20% of headache patients2,16,37). Approximately 3% to 54% of whiplash patients were reported to have CGH1,4,17,40). The considerable discrepancy in the reported prevalence rates was mainly attributed to the different diagnostic criteria for CGH. However, the diagnosis of CGH became more obvious with the diagnostic criteria of the CHISG41) and IHS27). We followed the CHISG criteria which include symptom precipitation from neck, anesthetic blockade effect, and unilaterality without side shift41). Bilateral headache can be acceptable as "unilaterality on two sides" which should be confirmed with bilateral anesthetic blockade41), but there was no bilateral case in our study. To confirm the positive anesthetic blockade effect, 0.5 mL of 1% lidocaine and 0.5% bupivacaine were injected consecutively with 1 week interval at each medial branch of C4-7, and pain relief (>90%) with bupivacaine should last at least 3 hours longer than that with lidocaine5). Even though we followed the same diagnostic procedures, it was relatively complicated and the patients suffered much inconvenience during the procedures. It seems that there should be a less complicated and less painful diagnostic method for CGH in the future.

Accompanying symptoms such as wide spread headache, blurred vision, dizziness, or tinnitus are common symptoms in other disorders causing headache. Therefore, CGH should be differentiated from migraine, tension headache, sinusitis, temporomandibular joint syndrome, visual problems, auditory disturbance, and cluster headache13,25,44). According to a study reporting that pressure pain threshold at the facets in the CGH was lower than migraine and tension headache, the pathophysiology of CGH thought to be different from other types of headaches11). There were three cases of glaucoma and two cases of herpes zoster among patients with occipital headache and neck pain (data not presented), and were excluded from this study.

Pathogenesis of CGH remains controversial, suggesting that almost all the structures around the neck may cause CGH. Facet joints30), cervical muscles21,36), intervertebral discs29), nerve roots23), vertebral arteries14) and uncovertebral joints20) were reportedly related to CGH. The greater and lesser occipital nerves and the third occipital nerve, branches of C2-3 roots, were reported to be responsible for CGH as well39). CGH related structures have their sensory connection with upper cervical nerve roots, which converge into the spinal tract of the trigeminal nucleus24) and can explain the spreading of pain to frontal and orbital areas from cervical disorders. However, according to a study blocking mid-cervical nerves for CGH11), the mid-cervical nerves were also related to CGH. This supports our data showing considerable effect of lower cervical RFN on CGH.

Although medication and physiotherapy have been used as the initial management for CGH, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation18), nerve block10,28), botulinum toxin injection25), and RFN6,7,12,43) have also been recommended for treatment of medically intractable CGH. The RFN was reported to be effective in approximately 80% of the CGH patients. In this study, the majority (93.8%) of neck patients was treated with conservative methods, and only a small portion of the patients (6.2%) required RFN. Lower cervical, C4-7, RFN was performed for lower CZJP with CGH (11 patients), and was considered effective for headache in 63.6% of the patients. Even though direct comparison is difficult, the rate of effectiveness of this study was considerably lower than that of other reports performed upper cervical RFN7,12,43). The relative ineffectiveness of lower cervical RFN not only emphasizes the contribution of upper cervical spinal nerves but also a considerable responsibility of lower cervical nerves to the CGH.

The VAS score slowly improved during the first week after RFN and then showed prominent improvement at one month. This clinical pattern after RFN, slow initial improvement, appears to be related to local pain at the electrode insertion sites.

There are limitations of this study. The original diagnosis of the patients enrolled in this study was not the CGH related with lower cervical disorder. They were known to have lower CZJP as a first impression, and then their headaches were noticed during the diagnostic process, which must be the problem related with retrospective study. We could not rule out the effect of other types of headache like migraine and tension headache or differentiate the effect of upper cervical region in the failed group. The number of patients was small, which seems to come from relatively complicated diagnostic method.

CONCLUSION

The results from the present study suggest that lower cervical disorders play a considerable role in the pathogenesis of CGH. Although upper cervical levels are the primary targets for treatment, lower cervical levels should not be overlooked in the treatment of CGH for better clinical results.

References

- 1.Anthony M. Cervicogenic headache : prevalence and response to local steroid therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:S59–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonaci F, Bono G, Mauri M, Drottning M, Buscone S. Concepts leading to the definition of the term cervicogenic headache : a historical overview. J Headache Pain. 2005;6:462–466. doi: 10.1007/s10194-005-0250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balla JI. The late whiplash syndrome. Aust N Z J Surg. 1980;50:610–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1980.tb04207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bansevicius D, Pareja JA. The "skin roll" test : a diagnostic test for cervicogenic headache? Funct Neurol. 1998;13:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnsley L, Lord S, Bogduk N. Comparative local anaesthetic blocks in the diagnosis of cervical zygapophysial joint pain. Pain. 1993;55:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90189-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blume HG. Cervicogenic headaches : radiofrequency neurotomy and the cervical disc and fusion. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:S53–S58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blume HG. Treatment of cervicogenic headaches : radiofrequency neurotomy to the sinuvertebral nerves to the upper cervical disc and to the outer layer of the C3 nerve root or C4 nerve root respectively. Funct Neurol. 1998;13:83–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogduk N. Cervicogenic headache : anatomic basis and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001;5:382–386. doi: 10.1007/s11916-001-0029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogduk N, Marsland A. On the concept of third occipital headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:775–780. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bono G, Antonaci F, Dario A, Clerici AM, Ghirmai S, Nappi G. Unilateral headaches and their relationship with cervicogenic headache. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:S11–S15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bovim G, Berg R, Dale LG. Cervicogenic headache : anesthetic blockades of cervical nerves (C2-C5) and facet joint (C2/C3) Pain. 1992;49:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chouret EE. The greater occipital neuralgia headache. Headache. 1967;7:33–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1967.hed0701033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Amico D, Leone M, Bussone G. Side-locked unilaterality and pain localization in long-lasting headaches : migraine, tension-type headache, and cervicogenic headache. Headache. 1994;34:526–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3409526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Araujo Lucas G, Laudanna A, Chopard RP, Raffaelli E., Jr Anatomy of the lesser occipital nerve in relation to cervicogenic headache. Clin Anat. 1994;7:90–96. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diener HC, Kaminski M, Stappert G, Stolke D, Schoch B. Lower cervical disc prolapse may cause cervicogenic headache : prospective study in patients undergoing surgery. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:1050–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drottning M, Staff PH, Sjaastad O. Cervicogenic headache after whiplash injury. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:288–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edmeads J. The cervical spine and headache. Neurology. 1988;38:1874–1878. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.12.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farina S, Granella F, Malferrari G, Manzoni GC. Headache and cervical spine disorders : classification and treatment with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Headache. 1986;26:431–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1986.hed2608431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng FL, Schofferman J. Chronic Neck Pain and Cervicogenic Headaches. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2003;5:493–498. doi: 10.1007/s11940-996-0017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fredriksen TA, Fougner R, Tangerud A, Sjaastad O. Cervicogenic headache. Radiological investigations concerning head/neck. Cephalalgia. 1989;9:139–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1989.0902139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freund BJ, Schwartz M. Treatment of chronic cervical-associated headache with botulinum toxin A : a pilot study. Headache. 2000;40:231–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gille O, Lavignolle B, Vital JM. Surgical treatment of greater occipital neuralgia by neurolysis of the greater occipital nerve and sectioning of the inferior oblique muscle. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:828–832. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000112069.37836.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grillo F. The differential diagnosis and therapy of headache. Swiss Ann Chiroprac. 1961;2:121–166. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hack G. Cervicogenic headache : new anatomical discovery provides the missing link. Chiroprac Rep. 1998;12:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haldeman S, Dagenais S. Cervicogenic headache : a critical review. Spine J. 2001;1:31–46. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(01)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haspeslagh SR, Van Suijlekom HA, Lamé IE, Kessels AG, van Kleef M, Weber WE. Randomised controlled trial of cervical radiofrequency lesions as a treatment for cervicogenic headache [ISRCTN07444684] BMC Anesthesiol. 2006;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders : 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinderaker J, Lord SM, Barnsley L, Bogduk N. Diagnostic value of C2-3 instantaneous axes of rotation in patients with headache of cervical origin. Cephalalgia. 1995;15:391–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.1505391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansen J, Bardosi A, Hildebrandt J, Lücke A. Cervicogenic, hemicranial attacks associated with vascular irritation or compression of the cervical nerve root C2. Clinical manifestations and morphological findings. Pain. 1989;39:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jull G, Barrett C, Magee R, Ho P. Further clinical clarification of the muscle dysfunction in cervical headache. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:179–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.1903179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JS, Roh JK, Ahn YO. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of tension-type headache in Korea. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1997;15:615–623. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leone M, D'Amico D, Grazzi L, Attanasio A, Bussone G. Cervicogenic headache : a critical review of the current diagnostic criteria. Pain. 1998;78:1–5. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00116-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, McDonald GJ, Bogduk N. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612053352302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macnab I. Chapter 14. Pain and disability in degenerative disc disease. Clin Neurosurg. 1973;20:193–196. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/20.cn_suppl_1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maimaris C, Barnes MR, Allen MJ. 'Whiplash injuries' of the neck : a retrospective study. Injury. 1988;19:393–396. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(88)90131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michler RP, Bovim G, Sjaastad O. Disorders in the lower cervical spine. A cause of unilateral headache? A case report. Headache. 1991;31:550–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1991.hed3108550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nilsson N. The prevalence of cervicogenic headache in a random population sample of 20-59 year olds. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:1884–1888. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park CH, Jeon EY, Chung JY, Kim BI, Roh WS, Cho SK. Application of pulsed radiofrequency for 3rd occipital neuralgia : a case report. J Korean Pain Soc. 2004;17:63–65. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pöllmann W, Keidel M, Pfaffenrath V. Headache and the cervical spine : a critical review. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:801–816. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1708801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sjaastad O, Fredriksen TA. Cervicogenic headache : criteria, classification and epidemiology. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:S3–S6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sjaastad O, Fredriksen TA, Pfaffenrath V The Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group. Cervicogenic headache : diagnostic criteria. Headache. 1998;38:442–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3806442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sjaastad O, Saunte C, Hovdahl H, Breivik H, Grønbaek E. "Cervicogenic" headache. An hypothesis. Cephalalgia. 1983;3:249–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1983.0304249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Suijlekom HA, van Kleef M, Barendse GA, Sluijter ME, Sjaastad O, Weber WE. Radiofrequency cervical zygapophyseal joint neurotomy for cervicogenic headache : a prospective study of 15 patients. Funct Neurol. 1998;13:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vincent MB, Luna RA. Cervicogenic headache : a comparison with migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(Suppl 25):11–16. doi: 10.1177/0333102499019s2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]