Abstract

Background

Hypotension remains a common clinical problem of spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery and phenylephrine is used as a vasopressor to address this. However, phenylephrine reduces maternal cardiac output (CO) due to reflex bradycardia. Glycopyrrolate is safe for the fetus, and increases heart rate (HR). Using a noninvasive measure of CO, we compared maternal hemodynamic changes between the phenylephrine only group (group P) and the phenylephrine plus glycopyrrolate group (group PG).

Methods

In this randomized study, 60 women scheduled for elective cesarean delivery were allocated to group P (n = 30) or group PG (n = 30). In both groups, phenylephrine was infused at 50 µg/min. This infusions stopped if systolic blood pressure (SBP) was higher than the baseline value, and phenylephrine 100 µg was injected if SBP was lower than 80% of the baseline value from spinal anesthesia to delivery. In group PG, glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg was injected intravenously after spinal anesthesia. Hemodynamic parameters, such as SBP, heart rate (HR), stroke volume index (SVI), cardiac index (CI) were measured before and until 15 min after spinal anesthesia.

Results

There were no significant differences in SBP and SVI compared to the baseline value in each group and between the two groups. HR and CI reduced significantly from 8 min to 15 min in group P compared to the baseline value as well as group PG for each time-point. However, HR and CI were maintained in group PG.

Conclusions

The use of glycopyrrolate added to phenylephrine infusion to prevent hypotension by spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery was effective in maintaining HR and CI.

Keywords: Cesarean section, Glycopyrrolate, Hypotension, Phenylephrine, Spinal anesthesia

Introduction

Despite many studies, hypotension during regional anesthesia for cesarean section is a common clinical problem. An essential measure is the use of vasopressors with preloading for preventing hypotension during regional anesthesia. The recent trend of vasopressor use is reduction of ephedrine preference. This is because ephedrine is associated with lower fetal pH and combinations of phenylephrine and ephedrine appear to have no advantage compared with phenylephrine alone [1]. Instead, phenylephrine infusion alone is established as a firstline vasopressor, because it does not appear to be harmful to the fetus when given in the dose range required to prevent hypotension, and be effective for hemodynamic control [2]. However, it reduces maternal cardiac output (CO) due to reflex bradycardia [3]. Therefore, this study was designed to compare phenylephrine infusion alone with phenylephrine infusion combined with glycopyrrolate to observe whether maternal CO was maintained by anticholinergic boluses during spinal anesthesia for cesarean section.

Materials and Methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the Cheil General Hospital institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from each patient. Sixty consecutive women scheduled for elective cesarean section under spinal anesthesia were approached for the study. Exclusion criteria included cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, pregnancy-related hypertensive disease, height < 150 cm or > 180 cm, weight < 50 kg or > 100 kg, known fetal abnormalities, contraindications to glycopyrrolate, fever, twin pregnancies, and diabetes mellitus

Randomization was performed using an Excel (Microsoft, USA) generated numbers. Parturients were randomly assigned to the phenylephrine only group (group P) or the phenylephrine combined with glycopyrrolate group (group PG). The patients had no premedication prior to the study. On arrival in the operating room, we tilted the operating table to the left by up to 15° and permitted the patients to rest undisturbed in the supine position for several minutes. Then we measured SBP and HR three times. Baseline SBP and HR were taken as the mean value of three recordings. We measured baseline CI and SVI simultaneously using a noninvasive cardiac output measuring device (Solar8000M, GE, USA).

With Hartmann solution fully loaded, we initiated spinal anesthesia. Spinal anesthesia was induced with patients in the left lateral position at the L3-4 or L4-5 vertebral interspace and 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine 10 mg and fentanyl 15 µg were injected intrathecally using a 25-gauge pencil point needle (25Pencan®, B/Braun, Germany).

After spinal anesthesia, the phenylephrine was infused at a rate of 50 µg/min in each group and glycopyrrolate was IV injected in group PG at the same time. We recorded systolic blood pressure (SBP), heart rate (HR), stroke volume index (SVI), cardiac index (CI) at 1 min intervals for 15 min. Hartmann solution was fully loaded for 15 min without exceeding 1,000 ml. The phenylephrine was infused at a rate of 50 µg/min for 15 min and the hemodynamic values were recorded. If the SBP was above the baseline, the infusion was stopped, and if it was at or below the baseline, the infusion was continued. After 15 min, we determined phenylephrine infusion rate within 80% of baseline SBP maintenance.

Hypotension, defined as a SBP ≤ 80% of baseline SBP for 2 consecutive readings, despite the phenylephrine infusion, was treated with a bolus of phenylephrine 100 µg if HR > 60 bpm and a bolus of ephedrine 10 mg if HR < 60 bpm. Bradycardia, defined as HR < 50 bpm for 2 consecutive readings, was treated by stopping the phenylephrine infusion if the SBP was at or above the baseline. However, if the SBP was below the baseline, the phenylephrine infusion was continued and a bolus of ephedrine 10 mg was administered. Total phenylephrine infusion dose was recorded for 15 min including bolus dose. Five minutes after intrathecal injection, we measured the upper sensory level of anesthesia by assessing loss of pinprick discrimination. We recorded skin incision time, uterine incision time, delivery time and measured each interval. The incision was delayed for the study until 15 minute after obtaining obstetrician agreement. After delivery, Apgar scores 1 and 5 min were recorded. Phenylephrine rescue and ephedrine rescue numbers were recorded.

Data were expressed as mean ± SD or median or number of patients. For statistical analysis, Sigma Stat software (version 3.5, IL, USA) was used. One-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni test was used for comparison of SBP, HR, SVI, and CI within each group. The student t test and Mann-Whitney rank sum test were used for measurements between the two groups. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

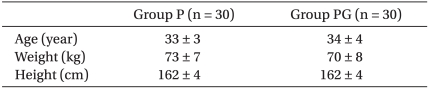

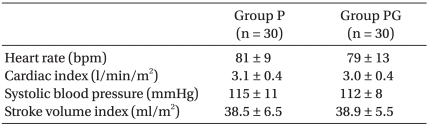

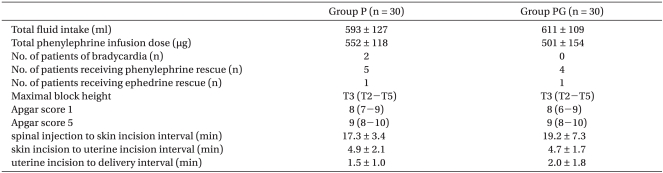

There were no statistical differences in demographic data and baseline cardiovascular values between the two groups (Table 1, 2, respectively). There were no statistical differences in experimental data between the two groups either (Table 3).

Table 1.

Maternal Characteristics

Values are mean ± SD. There were no significant differences between groups. Group P: phenylephrine alone group. Group PG: phenylephrine plus glycopyrrolate group.

Table 2.

Baseline Cardiovascular Values

Values are mean ± SD. There were no significant differences between groups. Group P: phenylephrine alone group. Group PG: phenylephrine plus glycopyrrolate group.

Table 3.

Experimental Data

Values are mean ± SD, number, or median. There were no significant differences between groups. Group P: phenylephrine alone group. Group PG: phenylephrine plus glycopyrrolate group.

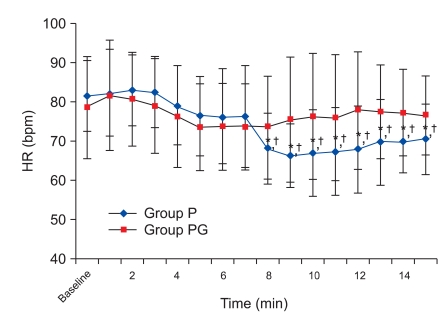

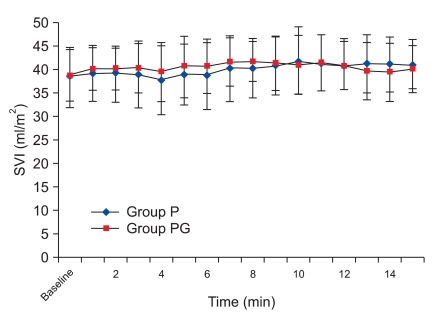

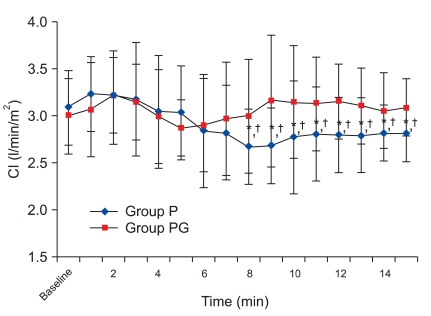

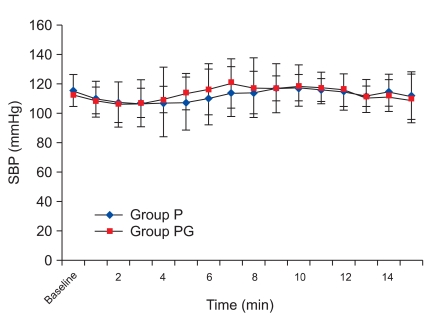

There was, however, a statistically significant decrease in HR at 8 min compared with the baseline values, which continued until 15 min in group P. There was a no significant difference in group PG. There was a significant decrease from 8 min to 15 min in group P compared with group PG (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in SVI compared with baseline values in each group and between the two groups (Fig. 2), but there was a statistically significant decrease in CI at 8 min compared to the baseline values, which continued until 15 min in group P, and there was a no significant difference in group PG. There was a significant decrease from 8 min to 15 min in group P compared with group PG (Fig. 3), but there was a no significant difference in SBP compared with baseline values in each group and between the two groups (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Heart rate changes during 15 minutes after spinal anesthesia. HR: heart rate. Group P: phenylephrine alone group. Group PG: phenylephrine plus glycopyrrolate group. *P < 0.05 compared to baseline value in group P. †P < 0.05 compared with group PG.

Fig. 2.

Stroke volume index changes during 15 minutes after spinal anesthesia. SVI: Stroke volume index. Group P: phenylephrine alone group. Group PG: phenylephrine plus glycopyrrolate group.

Fig. 3.

Cardiac index changes during 15 minutes after spinal anesthesia. CI: cardiac index. Group P: phenylephrine alone group. Group PG: phenylephrine plus glycopyrrolate group. *P < 0.05 compared to baseline value in group P. †P < 0.05 compared with group PG.

Fig. 4.

Systolic blood pressure changes during 15 minutes after spinal anesthesia. SBP: Systolic blood pressure. Group P: phenylephrine alone group. Group PG: phenylephrine plus glycopyrrolate group.

Discussion

Hypotension during regional anesthesia for cesarean section is a very common and severe clinical problem. Factors contributing to this include increased sensitivity to local anesthetics, aortocaval compression and increased susceptibility to the effects of sympathetic block [2]. Hypotension may cause nausea and vomiting, and long-term, severe hypotension may cause unconsciousness, pulmonary aspiration, hypoxia and acidosis, as well as Fetal neurological injury due to reduction of uteroplacental blood flow [4]. Management of hypotension during regional anesthesia includes positional change, fluid therapy, vasopressors, and other nonpharmacological methods [2]. Although positional change by tilt or wedge is considered to be necessary, this management does not prevent hypotension by aortocaval compression completely [5]. In addition, although colloids appear to be more effective than crystalloids [6], the decision to use them depends on individual assessment of benefits compared with potential disadvantages.

Recent studies compared prehydration with cohydration of colloids and there were only a few differences in hemodynamic change and vasopressin requirement [7-9]. Positional change and fluid loading did not prevent hypotension completely, which required other methods including vasopressor. Arai et al. [10] found that transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation at the Neiguan (PC-6) and Jianshi (PC-5) acupoints resulted in less hypotension and vasopressin requirement than the controls. Bjørnestad et al. [11] compared wrapping the legs with tight elastic bandages and applying intravenous boluses of phenylephrine 50 mg, given immediately and at 5 and 10 min after epidural block. They found no difference between groups in the incidence of hypotension. However, these techniques have not found wide acceptance in clinical practice.

There are many studies of alpha agonists like phenylephrine, which is now a trend in choice of vasopressors for preventing hypotension during regional anesthesia. In phenylephrine and ephedrine infusion combination studies, as the proportion of phenylephrine decreased and the proportion of ephedrine increased, the incidence of hypotension and nausea/vomiting increased and fetal pH and base excess reduced [1]. However, the ideal method of administration and dosing regimen for phenylephrine is controversial. Infusions titrated in the range of 25-100 µg/min are effective for maintaining maternal BP [12]. Phenylephrine does not appear to be harmful to the fetus when given in the dose range required to prevent hypotension and is highly effective [2]. However, phenylephrine cause reflex decreases in HR and reduce CO [3,13]. As the dosage of phenylephrine increase, BP maintenance is more effective but CO becomes more reduced. The role of reduced CO is unclear in clinical settings. Most studies of vasopressors have been made in healthy low-risk elective patients, so that the clinical impact of CO reduction caused by phenylephrine infusion is unclear. Ngan Kee et al. [14] reported that neonatal outcome and acid-base status was similar between two groups having non-elective spinal caesarean section to receive either phenylephrine or ephedrine boluses to treat hypotension including potential fetal compromise. However, CO reduction may result in the reduction of uteroplacental blood flow, and the impact may result in harmful influence on a potentially compromised fetus with reduced margin of safety for uteroplacental perfusion. Therefore, the measures compensating for CO reduction can become an ideal regimen.

CO reduction caused by phenylephrine administration is due to reduction of HR, but the stroke volume is well maintained [13]. Therefore, we assumed that anticholinergics maintain HR and CO. Although among anticholinergics, atropine is more effective than glycopyrrolate for HR increase, the placental transfer rate of atropine (F/M ratio; 0.93) is more than glycopyrrolate (F/M ratio; 0.22). Therefore, glycopyrrolate was predicted to be a safe drug to pregnant women because of significantly reduced effects on the fetus [15]. Glycopyrrolate has a longer duration of action than atropine [16], and the reduction of gastric juice volume and acidity is more beneficial to pregnant women [17]. Glycopyrrolate is consequently an ideal drug that can compensate CO reduction caused by phenylephrine administration. However, there are only a few reports on the appropriate dosage of glycopyrrolate. We selected 0.2 mg as the standard dosage.

We found that SVI were similar compared to the baseline values between the two groups, which was in accordance with other studies. However, there were continuous decreases in HR caused by phenylephrine infusion, and HR decreased statistically from 8 min to 15 min in group P. In accordance with HR, there were continuous decreases in CI, and CI maximally decreased at 8 min (approximately 13%). Following that, CI recovered gradually, but there were statistically significant decreases compared with baseline values in group P. Although there were decreasing trends in HR until 8 min in group PG, HR recovered and was maintained. CI was similar to HR in group PG, and there was a maximum difference (0.5 L/min/m2) at 9 min between the two groups.

This study showed that glycopyrrolate is an effective measure in maintaining HR and CI.

References

- 1.Ngan Kee WD, Lee A, Khaw KS, Ng FF, Karmakar MK, Gin T, et al. A randomized double-blinded comparison of phenylephrine and ephedrine combinations given by infusion to maintain blood pressure during spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery: effects on fetal acid-base status and hemodynamic control. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1295–1302. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818065bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ngan Kee WD. Prevention of maternal hypotension after regional anaesthesia for caesarean section. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010;23:304–309. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328337ffc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langesæter E, Rosseland LA, Stubhaug A. Continuous invasive blood pressure and cardiac output monitoring during cesarean delivery: a randomized, double-blind comparison of low-dose versus high-dose spinal anesthesia with intravenous phenylephrine or placebo infusion. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:856–863. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31818a401f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emmett RS, Cyna AM, Andrew M, Simmons SW. Techniques for preventing hypotension during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section (Review) The Cochrane Collaboration. 2010;11:1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharwood-Smith G, Drummond GB. Hypotension in obstetric spinal anaesthesia: a lesson from preeclampsia. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:291–294. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madi-Jebara S, Ghosn A, Sleilaty G, Richa F, Cherfane A, Haddad F, et al. Prevention of hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: 6% hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 (Voluven) versus lactated Ringer's solution. J Med Liban. 2008;56:203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teoh WH, Sia AT. Colloid preload versus coload for spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery: the effects on maternal cardiac output. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1592–1598. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31819e016d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvalho B, Mercier FJ, Riley ET, Brummel C, Cohen SE. Hetastarch co-loading is as effective as preloading for the prevention of hypotension following spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2009;18:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siddik-Sayyid SM, Nasr VG, Taha SK, Zbeide RA, Shehade JM, Al Alami AA, et al. A randomized trial comparing colloid preload to coload during spinal anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1219–1224. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181b2bd6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arai YC, Kato N, Matsura M, Ito H, Kandatsu N, Kunkawa S, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation at the PC-5 and PC-6 acupoints reduced the severity of hypotension after spinal anaesthesia in patients undergoing caesarean section. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:78–81. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjørnestad E, Iversen OE, Raeder J. Wrapping of the legs versus phenylephrine for reducing hypotension in parturients having epidural anaesthesia for caesarean section: a prospective, randomized and double-blind study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:842–846. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328329b028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smiley RM. Burden of proof. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:470–472. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b16466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart A, Fernando R, McDonald S, Hignett R, Jones T, Columb M. The dose-dependent effects of phenylephrine for elective cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:1230–1237. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181f2eae1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngan Kee WD, Khaw KS, Lau TK, Ng FF, Chui K, Ng KL. Randomised double-blinded comparison of phenylephrine vs ephedrine for maintaining blood pressure during spinal anaesthesia for non-elective Caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:1319–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zakowski MI, Herman NL. The placenta: Anatomy, physiology, and transfer of drugs. In: Chestnut DH, editor. Obstetric Anesthesia. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby, Inc; 2004. p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan GE, Jr, Mikhail MS, Murray MJ. Clinical Anesthesiology. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2006. p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salem MR, Wong AY, Mani M, Bennett EJ, Toyama T. Premedicant drugs and gastric juice pH and volume in pediatric patients. Anesthesiology. 1976;44:216–219. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]