Abstract

Increased vascular smooth muscle contractility has an important role in the development of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity is a major determinant of smooth muscle contractility. We investigated changes in the Ca2+-sensitizing effect of endothelin-1 (ET-1) and the mechanisms underlying ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization after SAH using a rabbit SAH model. After SAH, the contractile response to ET-1 was enhanced, and the ETA receptor expression was upregulated in the basilar artery. In α-toxin-permeabilized preparations, ET-1 induced enhanced and prolonged contraction after SAH, suggesting that ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization is potentiated after SAH. Endothelin-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization became less sensitive to inhibitors of Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase (ROCK) and protein kinase C (PKC) after SAH. The expression of PKCα, ROCK2, PKC-potentiated phosphatase inhibitor of 17 kDa (CPI-17) and myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 (MYPT1) was upregulated, and the level of phosphorylation of CPI-17 and MYPT1 was elevated after SAH. This study demonstrated for the first time that the Ca2+-sensitizing effect of ET-1 on myofilaments is potentiated after SAH. The increased expression and activity of PKCα, ROCK2, CPI-17, and MYPT1, as well as the upregulation of ETA receptor expression are suggested to underlie the enhanced and prolonged Ca2+ sensitization induced by ET-1.

Keywords: calcium, pharmacology, physiology, smooth muscle, subarachnoid hemorrhage, vasospasm

Introduction

Cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is characterized by delayed and prolonged contraction of cerebral arteries, which may cause cerebral ischemia and lead to death or neurologic deficits in patients with SAH (Kassell et al, 1985). Therefore, prevention and treatment of vasospasm have important roles in managing patients with SAH. The mechanism of cerebral vasospasm can be attributed to either increased production of spasmogens or increased vascular reactiveness (Kai et al, 2008). Among the various proposed spasmogens, endothelin-1 (ET-1) has been implicated as a critical mediator in the pathogenesis of cerebral vasospasm due to its inherent property of producing potent and prolonged vasoconstriction (Alafaci et al, 1990; Nakagomi et al, 1989). On the other hand, the increase in vascular reactiveness may result from either endothelial dysfunction (Kassell et al, 1985; Sasaki et al, 1985) or an increase in smooth muscle contractility (Kai et al, 2008). The upregulated expression of various receptors, including ETA receptors, which mediate the contractile effect of ET-1 (Feger et al, 1994; Goadsby et al, 1996), has been reported to contribute to the increased reactiveness of vascular smooth muscle after SAH (Ansar et al, 2007; Beg et al, 2006; Hansen-Schwartz et al, 2003; Itoh et al, 1994; Kikkawa et al, 2010; Maeda et al, 2007).

Smooth muscle contraction is primarily regulated by Ca2+-dependent reversible phosphorylation of the 20-kDa myosin regulatory light chain (Hirano, 2007). However, the relationship between the extent of elevation of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and the degree of the developed tension varies depending on the contractile stimulation. In general, receptor agonists produce greater tension for a given elevation of [Ca2+]i than membrane depolarization (Hirano, 2007). This phenomenon is referred to as Ca2+ sensitization of the contractile apparatus (Hirano, 2007). Regulation of myosin phosphatase activity has an important role in regulating myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (Hirano, 2007). Phosphorylation of the 110-kDa myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 (MYPT1) or the protein kinase C (PKC)-potentiated phosphatase inhibitor of 17 kDa (CPI-17) is associated with decreased activity of myosin phosphatase, thereby increasing myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (Eto, 2009; Hartshorne et al, 2004; Hirano, 2007; Ito et al, 2004). Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase (ROCK) phosphorylates both MYPT1 and CPI-17, whereas PKC phosphorylates CPI-17. Therefore, ROCK, PKC, MYPT1, and CPI-17 are key components of the mechanism that regulates myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. The increase in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity has an important role in the ET-1-induced contractile mechanism of vascular smooth muscle (Nishimura et al, 1992; Sakata et al, 1989; Scherer et al, 2002). However, whether ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitivity is altered after SAH and which components of the regulatory mechanism have a major role in ET-1-induced sensitization after SAH remain unclear.

Using a rabbit double hemorrhage model (Kikkawa et al, 2010), we investigated the changes in the effects of ET-1 on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and the mechanisms responsible for ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization after SAH. For this purpose, the basilar artery was used to examine the contractile response to ET-1, because the basilar artery was located in proximity to the site of clot formation in the rabbit SAH model. In patients with SAH, it has been reported that the sites of vasospasm closely correlate with those of clots (Kistler et al, 1983). The effects of ET-1 and inhibitors of ROCK and PKC on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity were evaluated in α-toxin-permeabilized preparations. The expression of ROCK, PKC, MYPT1, and CPI-17, as well as the phosphorylation state of MYPT1 and CPI-17, were evaluated to clarify the mechanisms of ET-1-mediated Ca2+ sensitization after SAH.

Materials and methods

Preparation of the Rabbit Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Model

The study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, Kyushu University. Adult male Japanese white rabbits (2.5 to 3.0 kg) were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of ketamine (40 mg/kg weight) and an intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital (20 mg/kg weight). On day 0, 0.5 mL of cerebrospinal fluid was aspirated percutaneously from the cisterna magna using a 23-gauge butterfly needle, and 2.5 mL of autologous arterial blood obtained from the ear artery was injected into cisterna magna. The animal was then kept in a prone position with the head tilting down at 30° for 30 minutes. On day 2, a second injection of autologous blood was similarly performed. Control animals received injections of normal physiological salt solution (PSS) at the same volume instead of the autologous blood. Of the 68 rabbits used as SAH models, 17 died during the perioperative period. The remaining 51 rabbits survived and were evaluated. Most of them manifested a transient appetite loss after autologous blood injection. However, none of them exhibited persistent appetite loss, significant weight loss, or neurologic deficits.

Preparation of Intact Basilar Artery Rings

On day 7, the rabbits were heparinized (400 U/kg weight) and then euthanized by intravenous injection of an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (120 mg/kg weight), followed by exsanguination from the common carotid artery. When the brain was exposed, the clots were observed over the surface of the pons and the basilar artery in rabbits with SAH. Immediately after excising the whole brain en bloc and removing the clot, binocular microscopy (Wild M7A, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) revealed narrowing of the basilar artery in SAH. The external diameter of the basilar artery was significantly reduced in SAH (0.49±0.05 mm, n=10) compared with controls (0.73±0.05 mm, n=10).

The basilar artery was then immediately excised and cut into 500 μm-wide ring preparations. In our current study, the contractile response of rabbit basilar arteries was examined in the absence of endothelium. To remove the endothelium, the internal surface of the arteries was rubbed with a hair. The removal of endothelium was confirmed by the loss of the relaxant response to acetylcholine. The ring preparations were kept in normal PSS at room temperature until use. These preparations were referred to as ‘intact' preparations, regardless of the absence of endothelium, in contrast to the ‘permeabilized' preparations (described below).

Simultaneous Measurement of Changes in the Cytosolic Ca2+ Concentration and Development of Tension in Intact Ring Preparations of the Basilar Artery

The arterial rings were loaded with a Ca2+ indicator dye, fura-2, as a form of acetoxymethylester, and then used for simultaneous measurements of changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and tension at 37°C, as previously described (Kikkawa et al, 2010). The preparations were equilibrated in normal PSS at 37°C for at least 60 minutes before starting the experiment. During the 60-minute equilibration period, the rings were stimulated with 118 mmol/L K+ every 15 minutes, and the resting load was increased in a stepwise manner until a final adjustment of 50 mg, which was the minimal load that produced maximal tension in response to 118 mmol/L K+. The changes in the fura-2 fluorescence intensities obtained with excitation at 340 nm (F340) and 380 nm (F380), and their ratio (F340/F380), were monitored with a CAM-230 fluorometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). The data were expressed as a percentage by assigning the values of the fluorescence ratio and tension obtained in normal PSS and those obtained at 5 minutes after stimulation with 118 mmol/L K+ PSS as 0% and 100%, respectively, unless otherwise specified.

Tension Measurement in α-Toxin-Permeabilized Preparations of Rabbit Basilar Artery

Arterial rings were permeabilized with 5,000 U/mL staphylococcal α-toxin in cytosolic substitution solution (CSS) for 30 minutes at 25°C, as previously described (Kikkawa et al, 2010; Maeda et al, 2007). The rings were then treated with 10 μmol/L A23187, a Ca2+ ionophore, in Ca2+-free CSS for 15 minutes to deplete the intracellular Ca2+ stores. These permeabilized ring preparations were mounted horizontally between two tungsten wires, stretched to 1.5-fold of their resting length, and then allowed to completely relax in Ca2+-free CSS for 15 minutes before starting the experiment. Tension development was recorded at 25°C with a force transducer U gauge (Minebea, Nagano, Japan).

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Expression of ETA and ETB Receptors

Total RNA was extracted from the rabbit basilar artery, after removing endothelium, using TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocols. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized at 42°C for 30 minutes using 200 ng of RNA template in a 20-μL reaction mixture containing high capacity RNA-to-cDNA master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with an ABI 2720 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). The cDNA was stored at −80°C until use in quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Real-time PCR was performed in triplicate in a 20-μL reaction mixture containing TaqMan Fast Universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), 1 μL cDNA, rabbit-specific TaqMan probes, and primers provided in the TaqMan gene expression assay kit (Applied Biosystems) using an ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an endogenous control. The PCR protocol was composed of initial denaturation at 95°C for 20 seconds, followed by 40 amplification cycles of 95°C for 3 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds. The data were analyzed with the comparative cycle threshold method. The relative amount of mRNA (E0/R0) of ETA and ETB was calculated with the Ct values for ETA and ETB mRNA (CtE), respectively, and the Ct values for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA (CtR) in the same sample using the formula E0/R0=2CtE−CtR, where E0 is the original amount of ETA or ETB mRNA and R0 is the original amount of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA. The levels of ETA and ETB expression on day 0 were assigned a value of 100%. The data were expressed as the mean values±s.e.m.

Immunoblot Analysis of the Expression of Protein Kinase C and Rho-Associated Coiled-Coil Protein Kinase

Isolated basilar arteries were homogenized in 50 mmol/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.5 mmol/L Na3VO4, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 5 μmol/L microcystin-LR, 10 μmol/L calpain inhibitor, and 10 μmol/L 4-aminidophenylmethane sulphonyl fluoride. The protein concentration of the lysate was determined with a Coomassie protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Equal amounts of total proteins (5 μg) were separated on 12.5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels for sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electropholesis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (0.2 μm pore size; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) skim milk (for ETA, PKCα, β, ɛ, γ, θ, and ζ) or 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (for PKCδ, ROCK1, and ROCK2) in 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 (Tween 20 containing Tris-buffered saline) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with primary antibodies: anti-ETA receptor (1:200), anti-PKCα (1:1,000), anti-PKCβ (1:1,000), anti-PKCɛ (1:1,000), anti-PKCγ (1:1,000), anti-PKCζ (1:200), anti-ROCK1 (1:200), anti-ROCK2 (1:1,000), anti-PKCδ (1:200), and anti-PKCθ (1:200), which were diluted in immunoreaction enhancer solution (Can Get Signal; Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), followed by a 1-hour incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:1,000). The immune complexes were detected using an ECL plus detection kit (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Light emission was detected and analyzed with VersaDoc 5000 and the computer program Quantity One (Bio-Rad). After chemiluminescence detection, the membranes were stained with naphthol blue black to visualize the bands corresponding to actin. The optical density of each band was normalized to that of the corresponding actin band.

Immunoblot Analysis of the Expression and Phosphorylation of CPI-17 and Myosin Phosphatase Target Subunit 1

Samples were obtained during tension measurement of the intact preparations. In brief, bathing buffer was promptly removed at the indicated time points, and the specimens were quickly frozen with liquid nitrogen to stop the reaction. The specimens were immediately transferred to 90% (v/v) acetone, 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid, and 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol prechilled at −80°C. After overnight fixation at −80°C, the specimens were extensively washed with acetone at room temperature to remove trichloroacetic acid. After the specimens were air-dried to remove acetone, cellular proteins were extracted in sample buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-hydroxymethyl aminomethane, 2% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.01% (w/v) NaN3, 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue, 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μmol/mL 4-aminidophenylmethane sulphonyl fluoride, and 5 μmol/L microcystin). The supernatant was heated to 100°C for 5 minutes, and equal volumes of samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electropholesis on 7.5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels for MYPT1 or 12% (w/v) for CPI-17. The proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad), which were blocked with 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in Tween 20 containing Tris-buffered saline overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with primary antibodies: anti-total MYPT1 (1:10,000), anti-total CPI-17 (1:200), anti-phospho-MYPT1 (1:2,000 for T696 and 1:200 for T853), and anti-phospho-CPI-17 (T38, 1:200) diluted in Can Get Signal (Toyobo), followed by a 1-hour incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:1,000). The immune complexes were detected and analyzed as described above. After chemiluminescence detection, the actin bands were visualized by naphthol blue black staining. The levels of total MYPT1 and CPI-17 were normalized to those of the corresponding actin bands. The levels of phosphorylated MYPT1 and CPI-17 were normalized to those of total MYPT1 and CPI-17, respectively.

Drugs and Solutions

Normal PSS was composed of 123 mmol/L NaCl, 4.7 mmol/L KCl, 1.25 mmol/L CaCl2, 1.2 mmol/L MgCl2, 1.2 mmol/L KH2PO4, 15.5 mmol/L NaHCO3, and 11.5 mmol/L -glucose. Physiological salt solution was aerated with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2, resulting in a pH of 7.4. High K+ PSS was prepared by replacing NaCl with equimolar KCl. Ca2+-free CSS was composed of 100 mmol/L potassium methanesulphonate, 2.2 mmol/L Na2ATP, 3.38 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L EGTA, 10 mmol/L creatine phosphate, and 20 mmol/L Tris-malate (pH 6.8). Cytosolic substitution solution containing the indicated concentration of free Ca2+ was prepared by adding an appropriate amount of CaCl2, while assuming the Ca2+-EGTA binding constant to be 106 L/mol (Kikkawa et al, 2010; Maeda et al, 2007). Staphylococcus aureus α-toxin and Y27632 were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Endothelin-1 was obtained from Peptide Institute Inc. (Osaka, Japan). Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester was purchased from Dojindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan). Mouse monoclonal anti-PKCα (#610107), anti-PKCβ (#610127), anti-PKCɛ (#610085), and anti-ROCK2 (#610624) antibodies were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY, USA). Mouse monoclonal anti-PKCγ (Sc-610085), anti-PKCζ (Sc-17781), anti-ROCK1 (Sc-17794), and anti-total CPI-17 (Sc-28378) antibodies, and rabbit polyclonal anti-PKCδ (Sc-213), anti-PKCθ (Sc-212), anti-phospho-MYPT1 (T853: Sc-17432-R), and anti-phospho-CPI-17 (Thr38: Sc-17560-R) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-MYPT1 (T696: ABS45) antibody was purchased from Millipore/Upstate (Billerica, MA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-ETA receptor (#16201) antibody was purchased from Immuno-Biological Laboratories (Fujioka, Japan). Mouse monoclonal anti-total MYPT1 antibody was obtained from BABCO (Berkley, CA, USA).

Data Analysis

The data are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. of the indicated experimental number. One basilar arterial preparation obtained from one animal was used for each experiment, and therefore the number of experiments (n value) also indicates the number of rabbits. An unpaired Student's t-test was used to determine statistical differences between the two groups. An analysis of variance followed by Dunn's post hoc test was used to determine statistical differences in a multiple comparison with the control data. A value of P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, unless otherwise specified.

Results

Contractile Effect of Endothelin-1 in the Rabbit Basilar Artery After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Stimulation with 118 mmol/L K+ induced similar contraction in the basilar artery isolated from control and SAH rabbits (Figure 1A). The absolute values of the tension induced by the 118 mmol/L K+ in SAH samples did not significantly differ from those in the control (Figure 1B). Therefore, the contractile response to 118 mmol/L K+ was recorded as a reference response at the beginning of each measurement, and was thus assigned a value of 100%. Evaluation of the concentration-dependent responses to ET-1 revealed significant enhancement of contractile responses to 3, 10, and 30 nmol/L in SAH samples compared with values in the control, whereas contraction obtained with 100 nmol/L ET-1 in SAH samples was similar to that in the control (Figures 1A and 1C). This leftward shift of the concentration-response curve was similar to that of the previous reports (Ansar et al, 2007; Hansen-Schwartz et al, 2003). In SAH samples, 100 nmol/L ET-1 induced large, sustained contraction with a sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i (Figure 1D). The degree of tension for a certain level of [Ca2+]i (the ratio of tension to [Ca2+]i) obtained at 12 minutes during the ET-1-induced contraction was significantly greater than that obtained at 5 minutes during the 118 mmol/L K+-induced contraction in SAH samples, thus suggesting that ET-1 increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Contractile responses of the rabbit basilar artery to high K+ depolarization and endothelin-1 (ET-1) in the control and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). (A–C) Representative recordings (A) and summaries (B, C) of the contractile effects of 118 mmol/L K+ and ET-1 at the indicated concentrations in the control and SAH samples. The level of tension induced by 118 mmol/L K+ depolarization was expressed as an absolute value (B; n=10), whereas the level of tension induced by ET-1 was expressed as a percentage of the contraction induced by 118 mmol/L K+ (C; n=7). (D) Representative recordings showing the changes in [Ca2+]i and tension induced by 118 mmol/L K+ and 100 nmol/L ET-1 in fura-2-loaded basilar arteries of SAH. (E) The ratio of %tension to %[Ca2+]i obtained at 5 and 12 minutes after the initiation of contraction with 118 mmol/L K+ and ET-1, respectively, are shown for SAH (n=6). Since the levels of [Ca2+]i and tension obtained at 5 minutes after initiation of contraction with 118 mmol/L K+ were assigned values of 100%, the ratio for the 118 mmol/L K+-induced contraction was 1.0. The data represent the mean±s.e.m. n.s., not significantly different; #P<0.05; *P<0.05 versus control.

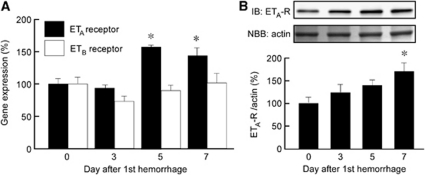

Upregulation of ETA Receptor Expression After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Quantitative real-time PCR showed significantly upregulated mRNA expression of ETA receptors in the basilar artery on days 5 and 7 after SAH, with a peak on day 5, whereas mRNA expression of the ETB receptor did not significantly change after SAH (Figure 2A). Immunoblotting demonstrated that expression of the ETA receptor protein was significantly upregulated on day 7 after SAH (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Time course of changes in ETA and ETB receptor expression in rabbit basilar artery during subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of ETA and ETB receptor expression (A) and immunoblot analysis of ETA receptor expression (B) in the basilar artery after SAH. Data are presented as mean values±s.e.m. (n=5 to 6). The level of expression seen on day 0 was assigned as 100%. *P<0.05 versus day 0. ET, endothelin.

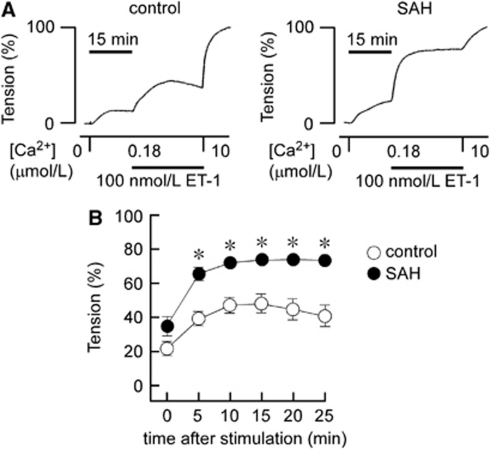

Changes in the Contractile Response to Endothelin-1 in α-Toxin-Permeabilized Rabbit Basilar Artery After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

The Ca2+-sensitizing effect of ET-1 was further investigated using α-toxin-permeabilized preparations. Changing Ca2+-free CSS to 180 nmol/L Ca2+ CSS caused similar contraction in both the control and SAH (Figures 3A and 3B). Subsequent application of 100 nmol/L ET-1 induced further development of tension in both the control and SAH (Figures 3A and 3B). However, the level of contraction seen in SAH samples was significantly higher than that seen in the control at any time point (Figures 3A and 3B). The contraction seen in the control gradually developed and then declined after reaching a peak at 10 minutes. The contraction seen in SAH samples rapidly developed to a peak, which was maintained for 25 minutes (Figures 3A and 3B). As a result, the Ca2+-sensitizing effect of ET-1 was enhanced and prolonged after SAH.

Figure 3.

Contractile responses to endothelin-1 (ET-1) in control and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) α-toxin-permeabilized rabbit basilar arteries. Representative recordings (A) and a summary (B) of the time course of contractions induced by 100 nmol/L ET-1 during 180 nmol/L Ca2+-induced contractions in α-toxin-permeabilized preparations of the control and SAH. The response to 10 μmol/L Ca2+ was recorded as a reference response at the end of each experiment, and this level of tension was assigned a value of 100%, whereas that obtained in Ca2+-free cytosolic substitution solution (CSS) was assigned a value of 0%. The data represent the mean±s.e.m. (n=10). n.s., not significantly different; *P<0.05 versus control at each time point.

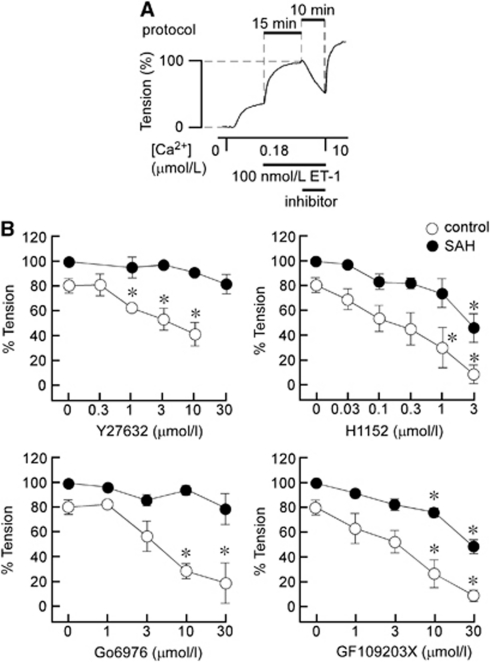

The Effects of Inhibitors of Rho-Associated Coiled-Coil Protein Kinase and Protein Kinase C on Endothelin-1-Induced Contraction in α-Toxin-Permeabilized Rabbit Basilar Artery

The roles of ROCK and PKC in ET-1-induced myofilament Ca2+ sensitization were evaluated by examining the effect of ROCK inhibitors (Y27632 and H1152) and PKC inhibitors (Go6976 and GF109203X) on ET-1-induced contraction in α-toxin-permeabilized preparations (Figure 4A). Under these conditions, contraction was induced by 100 nmol/L ET-1 during precontraction in 180 nmol/L Ca2+. Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase and PKC inhibitors were added 15 minutes after initiation of the contraction, and the effects were evaluated 10 minutes after application (Figure 4A). At the end of the measurements, the preparations were challenged with 10 μmol/L Ca2+. The level of contraction obtained just before the application of inhibitors was thus assigned a value of 100% (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

The effects of inhibitors of Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase (ROCK) and protein kinase C (PKC) on the contractions induced by endothelin-1 (ET-1) in α-toxin-permeabilized rabbit basilar artery. (A) Representative recording obtained with 10 μmol/L Y27632 in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) samples depicting the experimental protocol; the inhibitors were applied 15 minutes after initiation of contraction by 100 nmol/L ET-1 during 180 nmol/L Ca2+-induced precontractions, and their effects were evaluated 10 minutes after the applications. The effects of the inhibitors were evaluated by assigning the level of tension obtained just before the application of inhibitors and that obtained in Ca2+-free cytosolic substitution solution (CSS) to be 100% and 0%, respectively. (B) Concentration-dependent effects of Y27632, H1152, Go6976, and GF109203X on the contraction induced by 100 nmol/L ET-1 in α-toxin-permeabilized control and SAH arteries. Since ET-1-induced contraction declined slightly after reaching a peak at 15 minutes in the control (Figure 3), the time-matched control values (at zero concentration) were ∼80%. On the other hand, because ET-1-induced contraction was sustained in SAH samples, the time-matched control values were ∼100%. The data represent the mean±s.e.m. (n=5). *P<0.01 versus the values obtained with 0 μmol/L.

Y27632 significantly inhibited ET-1-induced contraction in the control, whereas it had no significant effect on ET-1-induced contraction in SAH samples, even at 30 μmol/L. H1152 also significantly inhibited ET-1-induced contraction at concentrations >0.3 μmol/L in the control, whereas contraction was significantly inhibited only at 3 μmol/L in SAH samples. On the other hand, Go6976, an inhibitor of the conventional type of PKC (Martiny-Baron et al, 1993), significantly inhibited ET-1-induced contraction in the control, but had no significant effect on ET-1-induced contraction in SAH samples, even at 30 μmol/L (Figure 4B). GF109203X, an inhibitor of both conventional and novel types of PKC (Toullec et al, 1991), significantly inhibited contraction at concentrations >3 μmol/L in both the control and SAH samples. As a result, ET-1-induced myofilament Ca2+ sensitization was more resistant to inhibitors of ROCK and PKC after SAH compared with the control.

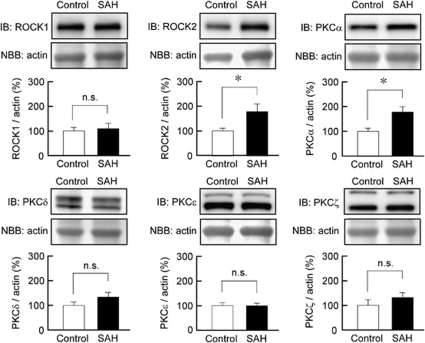

Changes in the Expression of Rho-Associated Coiled-Coil Protein Kinase and Protein Kinase C Isoforms in Rabbit Basilar Artery After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that ROCK2 expression was significantly increased in rabbit basilar artery after SAH, whereas the level of ROCK1 expression was similar in both the control and SAH samples (Figure 5). Among the isoforms of PKC (α, β, γ, δ, ɛ, θ, and ζ), the expression of PKCα, δ, ɛ, and ζ was detected in rabbit basilar artery by immunoblot analysis (Figure 5). Protein kinase Cα expression was significantly increased in SAH samples, whereas the level of expression of PKCδ, ɛ, and ζ remained unchanged after SAH. Protein kinase Cβ was not detected in the rabbit basilar artery in either the control or SAH samples, whereas it was detected in rabbit brain tissue (data not shown). Protein kinase Cγ and PKCθ were not detected in either rabbit basilar artery or rabbit brain with the antibodies used in our current study.

Figure 5.

Immunoblot (IB) analysis of the expression of Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase (ROCK) and protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms in rabbit basilar artery. Representative IB and summaries of the expression of ROCK1, ROCK2, PKCα, PKCδ, PKCɛ, and PKCζ in the basilar artery of the control and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) samples. The corresponding actin bands were visualized by naphthol blue black (NBB) staining. The level of expression seen in the control was assigned to be 100%. The data represent the mean±s.e.m. (n=6 to 7). n.s., not significantly different; *P<0.05.

The Expression and Phosphorylation of CPI-17 and Myosin Phosphatase Target Subunit 1 in Rabbit Basilar Artery

The level of expression of CPI-17 and MYPT1 significantly increased after SAH by ∼2.7- and 1.7-fold, respectively (Figures 6A and 6B). The basal levels of CPI-17 phosphorylation at the residue corresponding to T38 in humans, and MYPT1 at the residue corresponding to T853 in humans, significantly increased after SAH by ∼1.6- and 1.8-fold, respectively, even after normalization to the total level of expression. However, the level of phosphorylation of MYPT1 at the residue corresponding to T696 in humans remained unchanged after SAH (Figures 6A–6C).

Figure 6.

Immunoblot analysis of the expression and phosphorylation of protein kinase C-dependent phosphatase inhibitor of 17 kDa (CPI-17), and myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 (MYPT1) in rabbit basilar artery. Representative immunoblots (A) and summaries (B, C) of the levels of expression of total CPI-17, total MYPT1, phosphorylated CPI-17 at the residue corresponding to T38 in human CPI-17, and phosphorylated MYPT1 at the residues corresponding to T696 and T853 in human MYPT1, in the basilar artery of the control and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) samples. The level of expression in the control was assigned to be 100%. The corresponding actin bands were visualized by naphthol blue black (NBB) staining. The data represent the mean±s.e.m. (n=6). n.s., not significantly different; *P<0.05.

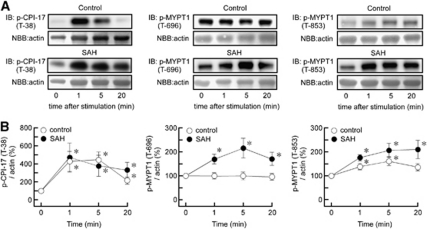

Time Course of Phosphorylation of CPI-17 and Myosin Phosphatase Target Subunit 1 during Endothelin-1-Induced Contraction in Rabbit Basilar Artery

In our current study, the time course of ET-1-induced phosphorylation of CPI-17 and MYPT1 was evaluated by assigning the value at the resting state (0 minutes) to be 100% in each animal group. Therefore, the comparison of the time course between the control and SAH groups do not reflect a comparison of the absolute level of phosphorylation. Endothelin-1 significantly increased the level of phosphorylation of CPI-17 at T38 by approximately fourfold at 1 minute in both the control and SAH samples (Figure 7). The level of T38 phosphorylation rapidly reached a peak within 1 minute in both control and SAH samples. Thereafter, the phosphorylation level gradually decreased in the control, and to a much weaker extent in SAH samples. Endothelin-1 did not induce any changes in the phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T696 in the control. However, the level of phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T696 increased by twofold at 5 minutes after stimulation with ET-1 in SAH samples (Figure 7). In the control, ET-1 induced phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T853, with a 1.5-fold peak increase at 5 minutes that developed gradually and declined over time. In SAH samples, ET-1 induced a greater level of phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T853, which was sustained for 20 minutes.

Figure 7.

Changes in the phosphorylation of protein kinase C-dependent phosphatase inhibitor of 17 kDa (CPI-17) and myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 (MYPT1) during endothelin-1 (ET-1)-induced contraction in rabbit basilar artery. Representative immunoblots (IB) (A) and summaries (B) of the levels of phosphorylation of CPI-17 at T38 and MYPT1 at T696 and T853 at the indicated times after stimulation with 100 nmol/L ET-1 in the control and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) samples. The corresponding actin bands were visualized by naphthol blue black (NBB) staining. The level of expression at time 0 was assigned to be 100%. The data represent the mean±s.e.m. (n=5). *P<0.05 versus time 0.

Discussion

Our current study demonstrated that after SAH, the contractile response to ET-1 was enhanced and the expression of ETA receptor mRNA and protein was upregulated in the basilar artery. The upregulation of ETA, but not of ETB receptors appears to be consistent with the notion that ETA is expressed in smooth muscle and mediates the contractile effect of ET-1 (Feger et al, 1994; Goadsby et al, 1996). The transcriptional upregulation of ETA receptors was suggested to contribute to the increased reactiveness to ET-1 after SAH. The novelty of our current study resides in the following major findings: (1) the sensitizing effect of ET-1 on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was not only enhanced, but also prolonged after SAH; (2) the expression of ROCK and PKC was upregulated in an isoform-specific manner; (3) the basal levels of both expression and phosphorylation of CPI-17 and MYPT1 (T853) increased after SAH; and (4) ET-1 induced prolonged phosphorylation of MYPT1 at both T696 and T853. Accordingly, these results suggest that in addition to upregulation of receptors, the increased expression and activity of key components involved in regulating myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity may underlie the potentiation of the sensitizing effect of ET-1 on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and the increased total reactiveness to ET-1 after SAH. The Ca2+-sensitizing effect of ET-1 is also supported by observations obtained from intact ring preparations, showing that the ratio of the level of developed tension to the level of [Ca2+]i seen with ET-1 was significantly higher than that obtained with 118 mmol/L K+ depolarization. However, use of α-toxin-permeabilized preparations allowed direct exploration into the mechanisms of the sensitizing effect of ET-1 on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, and the first demonstration of the potentiation of myofilament Ca2+ sensitization as a mechanism underlying the increased vascular contractility after SAH.

In α-toxin-permeabilized preparations, ET-1 induced further development of tension when the Ca2+ concentration was fixed at 180 nmol/L. This observation directly indicates that ET-1 increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. Development of tension exhibited a transient time course in control arteries, whereas it exhibited a sustained time course in SAH samples. We previously reported that contraction induced by GTPγS in α-toxin-permeabilized basilar artery is converted to sustained contraction after SAH (Kikkawa et al, 2010). We also showed that receptor desensitization is impaired after SAH, thus generating prolonged intracellular signaling (Kikkawa et al, 2010). Therefore, prolonged Ca2+ sensitization by ET-1 after SAH is suggested to be due to impaired feedback regulation in the signal transduction process that is located downstream of G proteins, as well as impaired feedback regulation of receptor activity.

The Ca2+-sensitizing effect of ET-1 on myofilaments became more resistant to inhibitors of ROCK and PKC after SAH. Although Y27632, H1152, and Go6976 significantly inhibited ET-1-induced contraction in the control, Y27632 and Go6976 exerted little inhibitory effect in SAH samples, and H1152 became less effective after SAH. However, GF109203X exhibited a similar inhibitory effect in both the control and SAH. Resistance to these inhibitors could be due to either decreased or increased contributions of ROCK and PKC to ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization. GF109203X inhibits both conventional and novel types of PKC, whereas Go6976 is more specific to the conventional type (Martiny-Baron et al, 1993; Toullec et al, 1991). The changes in the activity of the conventional type of PKC therefore suggested to be responsible for the increased resistance to the PKC inhibitor seen after SAH. Immunoblot analysis revealed upregulation of the expression of PKCα, a conventional type of PKC, after SAH, whereas the expression of PKCδ (novel type), PKCɛ (novel type), and PKCζ (atypical type) remained unchanged. The activation of PKC has been reported to be involved in the development of cerebral vasospasm (Laher and Zhang, 2001). Previous studies demonstrated a greater degree of membrane translocation of PKCα in SAH samples than that seen in the control, suggesting enhanced activation of PKCα after SAH (Nishizawa et al, 2000; Sato et al, 1997). As a result, increased expression and probably increased activity of PKCα are suggested to be responsible for attenuation of the inhibitory effect of Go6976 on ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization after SAH.

Similarly, the upregulation and increased activity of ROCK may be responsible for attenuation of the inhibitory effect of ROCK inhibitors on ET-1-induced myofilament Ca2+ sensitization after SAH. Our current study demonstrated upregulation of the expression of ROCK2, but not ROCK1, after SAH, suggesting that ROCK2 has a predominant role in the potentiation of myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity after SAH. This observation is consistent with a previous study, which reported that ROCK2 is the predominant isoform that regulates the contractility of vascular smooth muscle (Wang et al, 2009). Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase phosphorylates MYPT1 at both T853 and T696 (in humans), with a threefold preference for T853 over T696 (Hagerty et al, 2007). However, T696, but not T853, can be phosphorylated by other kinases including zipper-interacting protein kinase (Borman et al, 2002; MacDonald et al, 2001; Niiro and Ikebe, 2001) and integrin-linked kinase (Muranyi et al, 2002). Therefore, the phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T853 indicates ROCK activity. Our current study revealed a 1.8-fold increase in the phosphorylation level of MYPT1 at T853 under basal conditions, thus suggesting increased activity of ROCK after SAH. The observations in our current study are thus consistent with those reported in previous studies, which suggested that upregulation and activation of ROCK have an important role in the development of cerebral vasospasm (Sato et al, 2000). In this regard, the clinical efficacy of ROCK inhibitors, such as fasudil hydrochloride, to prevent cerebral vasospasm may be limited, especially when ROCK is over-activated after SAH.

The RhoA-ROCK pathway can be activated in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Sakurada et al, 2003). Indeed, the inhibitory effects of pharmacological inhibitors of ROCK have suggested that ROCK is involved in the sustained phase of the K+-depolarization-induced contraction (Mita et al, 2002). However, the present study found that the absolute value of the tension induced by 118 mmol/L K+ in SAH was similar to that in the control. The time course of the contraction was also similar between the two groups (data not shown). Our observations thus suggest that the contribution of ROCK to the 118 mmol/L K+-induced contraction is negligible in the rabbit basilar artery.

The basal level of CPI-17 phosphorylation at T38 was also increased after SAH. Furthermore, the level of CPI-17 phosphorylation rapidly reached a peak within 1 minute after ET-1 stimulation in both control and SAH samples. Thereafter, the phosphorylation level gradually decreased in the control, and to a much weaker extent in SAH samples. CPI-17 can be phosphorylated by ROCK and PKC (Eto, 2009; Hirano, 2007). Therefore, the increased phosphorylation of CPI-17 is consistent with the increased expression and activity of ROCK and PKC in SAH samples. However, the time course of CPI-17 phosphorylation was not consistent with the sustained nature of ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization after SAH. CPI-17 phosphorylation thus appeared to be associated with the initial phase of ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization. A previous study reported that the initial rapid phase of agonist-induced Ca2+ sensitization is dependent on rapid phosphorylation of CPI-17, which relies on Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and the activity of Ca2+-dependent conventional PKC (Dimopoulos et al, 2007). On the other hand, ET-1-induced phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T853 exhibited a transient time course in the control, whereas it was converted to a sustained response after SAH. This conversion of the time course of ET-1-induced MYPT1 phosphorylation is consistent with that seen with ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization in α-toxin-permeabilized preparations. Moreover, the observations in our current study are consistent with our previous observations that the time course of GTPγS-induced Ca2+ sensitization was converted to a sustained response after SAH (Kikkawa et al, 2010). Therefore, the prolongation of ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization after SAH is suggested to be mainly due to sustained activation of ROCK and the resulting sustained phosphorylation of MYPT1. In this respect, PKCα, but not ROCK, is suggested to have a major role in the phosphorylation of CPI-17, especially after SAH.

Endothelin-1 induced no changes in the phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T696 in the control. This observation is consistent with previous studies, showing that T696 phosphorylation does not increase during agonist-induced or myogenic contraction in various vascular smooth muscle tissues, including the cerebral arteries (Johnson et al, 2009; Kitazawa et al, 2003; Niiro et al, 2003; Wilson et al, 2005). On the other hand, ET-1 induced a gradually developing phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T696 after SAH. Phosphorylation of MYPT1 at both T696 and T853 is associated with decreased activity of myosin phosphatase (Khromov et al, 2009; Muranyi et al, 2005). Phosphorylation at T696 therefore suggested to contribute to the enhanced and sustained ET-1-induced Ca2+ sensitization after SAH. The increased phosphorylation at T696 was shown to be ROCK dependent in the rat cerebral artery under combined agonist and myogenic stimulation (El-Yazbi et al, 2010). T696 appears to be phosphorylated by ROCK when ROCK activity is augmented. Thus, ROCK might mediate ET-1-induced phosphorylation at T696 after SAH. T696 is phosphorylated by not only ROCK but also other kinases such as zipper-interacting protein kinase and integrin-linked kinase (Hartshorne et al, 2004; Hirano, 2007; Ito et al, 2004). Therefore, the contribution of ROCK as well as other kinases remains to be elucidated.

In conclusion, our current study demonstrated for the first time that the Ca2+-sensitizing effect of ET-1 on myofilaments was both enhanced and prolonged after SAH, thus contributing to the increased reactiveness of the basilar artery to ET-1. The enhancement of the Ca2+-sensitizing effect of ET-1 was suggested to be due to the increased expression and activation of PKC and ROCK, especially PKCα and ROCK2. Protein kinase Cα is mainly associated with enhanced but transient phosphorylation of CPI-17, whereas ROCK2 is mainly associated with enhanced and prolonged phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T853, and possibly at T696. In addition to the enhancement of the Ca2+-sensitizing effect of ET-1, the upregulation of ETA receptors also contributes to the increased contractile response to ET-1. Regulation of myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity as well as the Ca2+ signal is essential in agonist-induced vasoconstriction. The observed potentiation of Ca2+-sensitizing mechanisms is thus suggested to contribute to the increased vascular reactiveness to various spasmogens, and thus potentially has a fundamental role in the development of cerebral vasospasm after SAH.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Kristine De La Torre for linguistic and help with manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aids for Scientific Research (Nos. 22249054 and 20590883) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and the Adaptable and Seamless Technology Transfer Program through Target-driven R&D (A-STEP) from the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

References

- Alafaci C, Jansen I, Arbab MA, Shiokawa Y, Svendgaard NA, Edvinsson L. Enhanced vasoconstrictor effect of endothelin in cerebral arteries from rats with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Physiol Scand. 1990;138:317–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1990.tb08852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansar S, Vikman P, Nielsen M, Edvinsson L. Cerebrovascular ETB, 5-HT1B, and AT1 receptor upregulation correlates with reduction in regional CBF after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3750–H3758. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00857.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg SA, Hansen-Schwartz JA, Vikman PJ, Xu CB, Edvinsson LI. ERK1/2 inhibition attenuates cerebral blood flow reduction and abolishes ETB and 5-HT1B receptor upregulation after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:846–856. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borman MA, MacDonald JA, Muranyi A, Hartshorne DJ, Haystead TA. Smooth muscle myosin phosphatase-associated kinase induces Ca2+ sensitization via myosin phosphatase inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23441–23446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos GJ, Semba S, Kitazawa K, Eto M, Kitazawa T. Ca2+-dependent rapid Ca2+ sensitization of contraction in arterial smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2007;100:121–129. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000253902.90489.df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Yazbi AF, Johnson RP, Walsh EJ, Takeya K, Walsh MP, Cole WC. Pressure-dependent contribution of Rho kinase-mediated calcium sensitization in serotonin-evoked vasoconstriction of rat cerebral arteries. J Physiol. 2010;588:1747–1762. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto M. Regulation of cellular protein phosphatase-1 (PP1) by phosphorylation of the CPI-17 family, C-kinase-activated PP1 inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35273–35277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.059972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feger GI, Schilling L, Ehrenreich H, Wahl M. Endothelin-induced contraction and relaxation of rat isolated basilar artery: effect of BQ-123. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994;14:845–852. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goadsby PJ, Adner M, Edvinsson L. Characterization of endothelin receptors in the cerebral vasculature and their lack of effect on spreading depression. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:698–704. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199607000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty L, Weitzel DH, Chambers J, Fortner CN, Brush MH, Loiselle D, Hosoya H, Haystead TA. ROCK1 phosphorylates and activates zipper-interacting protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4884–4893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen-Schwartz J, Hoel NL, Xu CB, Svendgaard NA, Edvinsson L. Subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced upregulation of the 5-HT1B receptor in cerebral arteries in rats. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:115–120. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.1.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne DJ, Ito M, Erdodi F. Role of protein phosphatase type 1 in contractile functions: myosin phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37211–37214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K. Current topics in the regulatory mechanism underlying the Ca2+ sensitization of the contractile apparatus in vascular smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;104:109–115. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cp0070027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Nakano T, Erdodi F, Hartshorne DJ. Myosin phosphatase: structure, regulation and function. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;259:197–209. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000021373.14288.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh S, Sasaki T, Asai A, Kuchino Y. Prevention of delayed vasospasm by an endothelin ETA receptor antagonist, BQ-123: change of ETA receptor mRNA expression in a canine subarachnoid hemorrhage model. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:759–764. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.5.0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RP, El-Yazbi AF, Takeya K, Walsh EJ, Walsh MP, Cole WC. Ca2+ sensitization via phosphorylation of myosin phosphatase targeting subunit at threonine-855 by Rho kinase contributes to the arterial myogenic response. J Physiol. 2009;587:2537–2553. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.168252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai Y, Maeda Y, Sasaki T, Kanaide H, Hirano K. Basic and translational research on proteinase-activated receptors: the role of thrombin receptor in cerebral vasospasm in subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;108:426–432. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08r11fm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassell NF, Sasaki T, Colohan AR, Nazar G. Cerebral vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1985;16:562–572. doi: 10.1161/01.str.16.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khromov A, Choudhury N, Stevenson AS, Somlyo AV, Eto M. Phosphorylation-dependent autoinhibition of myosin light chain phosphatase accounts for Ca2+ sensitization force of smooth muscle contraction. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21569–21579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa Y, Kameda K, Hirano M, Sasaki T, Hirano K. Impaired feedback regulation of the receptor activity and the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity contributes to increased vascular reactiveness after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1637–1650. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistler JP, Crowell RM, Davis KR, Heros R, Ojemann RG, Zervas T, Fisher CM. The relation of cerebral vasospasm to the extent and location of subarachnoid blood visualized by CT scan: a prospective study. Neurology. 1983;33:424–436. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa T, Eto M, Woodsome TP, Khalequzzaman M. Phosphorylation of the myosin phosphatase targeting subunit and CPI-17 during Ca2+ sensitization in rabbit smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2003;546:879–889. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laher I, Zhang JH. Protein kinase C and cerebral vasospasm. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:887–906. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JA, Borman MA, Muranyi A, Somlyo AV, Hartshorne DJ, Haystead TA. Identification of the endogenous smooth muscle myosin phosphatase-associated kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2419–2424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041331498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Hirano K, Kai Y, Hirano M, Suzuki SO, Sasaki T, Kanaide H. Up-regulation of proteinase-activated receptor 1 and increased contractile responses to thrombin after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:1131–1139. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiny-Baron G, Kazanietz MG, Mischak H, Blumberg PM, Kochs G, Hug H, Marme D, Schachtele C. Selective inhibition of protein kinase C isozymes by the indolocarbazole Go 6976. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9194–9197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita M, Yanagihara H, Hishinuma S, Saito M, Walsh MP. Membrane depolarization-induced contraction of rat caudal arterial smooth muscle involves Rho-associated kinase. Biochem J. 2002;364:431–440. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranyi A, Derkach D, Erdodi F, Kiss A, Ito M, Hartshorne DJ. Phosphorylation of Thr695 and Thr850 on the myosin phosphatase target subunit: inhibitory effects and occurrence in A7r5 cells. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6611–6615. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranyi A, MacDonald JA, Deng JT, Wilson DP, Haystead TA, Walsh MP, Erdodi F, Kiss E, Wu Y, Hartshorne DJ. Phosphorylation of the myosin phosphatase target subunit by integrin-linked kinase. Biochem J. 2002;366:211–216. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagomi T, Ide K, Yamakawa K, Sasaki T, Kurihara H, Saito I, Takakura K. Pharmacological effect of endothelin, an endothelium-derived vasoconstrictive peptide, on canine basilar arteries. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1989;29:967–974. doi: 10.2176/nmc.29.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiro N, Ikebe M. Zipper-interacting protein kinase induces Ca(2+)-free smooth muscle contraction via myosin light chain phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29567–29574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiro N, Koga Y, Ikebe M. Agonist-induced changes in the phosphorylation of the myosin- binding subunit of myosin light chain phosphatase and CPI17, two regulatory factors of myosin light chain phosphatase, in smooth muscle. Biochem J. 2003;369:117–128. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura J, Moreland S, Ahn HY, Kawase T, Moreland RS, van Breemen C. Endothelin increases myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in alpha-toxin-permeabilized rabbit mesenteric artery. Circ Res. 1992;71:951–959. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.4.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa S, Obara K, Nakayama K, Koide H, Yokoyama T, Yokota N, Ohta S. Protein kinase C δ and α are involved in the development of vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata K, Ozaki H, Kwon SC, Karaki H. Effects of endothelin on the mechanical activity and cytosolic calcium level of various types of smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;98:483–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurada S, Takuwa N, Sugimoto N, Wang Y, Seto M, Sasaki Y, Takuwa Y. Ca2+-dependent activation of Rho and Rho kinase in membrane depolarization-induced and receptor stimulation-induced vascular smooth muscle contraction. Circ Res. 2003;93:548–556. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000090998.08629.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kassell NF, Yamashita M, Fujiwara S, Zuccarello M. Barrier disruption in the major cerebral arteries following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:433–440. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.63.3.0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Tani E, Matsumoto T, Fujikawa H, Imajoh-Ohmi S. Generation of the catalytic fragment of protein kinase C alpha in spastic canine basilar artery. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:752–756. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.5.0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Tani E, Fujikawa H, Kaibuchi K. Involvement of Rho-kinase-mediated phosphorylation of myosin light chain in enhancement of cerebral vasospasm. Circ Res. 2000;87:195–200. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer EQ, Herzog M, Wangemann P. Endothelin-1-induced vasospasms of spiral modiolar artery are mediated by rho-kinase-induced Ca2+ sensitization of contractile apparatus and reversed by calcitonin gene-related Peptide. Stroke. 2002;33:2965–2971. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000043673.22993.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, Grand-Perret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Boissin P, Boursier E, Loriolle F, Duhamel L, Charon D, Kirilovsky J. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zheng XR, Riddick N, Bryden M, Baur W, Zhang X, Surks HK. ROCK isoform regulation of myosin phosphatase and contractility in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2009;104:531–540. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DP, Susnjar M, Kiss E, Sutherland C, Walsh MP. Thromboxane A2-induced contraction of rat caudal arterial smooth muscle involves activation of Ca2+ entry and Ca2+ sensitization: Rho-associated kinase-mediated phosphorylation of MYPT1 at Thr-855, but not Thr-697. Biochem J. 2005;389:763–774. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]