Abstract

Objective To assess the cost effectiveness of screening men aged 65 for abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Design Cost effectiveness analysis based on a probabilistic, enhanced economic decision analytical model from screening to death.

Population and setting Hypothetical population of men aged 65 invited (or not invited) for ultrasound screening in the Danish healthcare system.

Data sources Published results from randomised trials and observational epidemiological studies retrieved from electronic bibliographic databases, and supplementary data obtained from the Danish Vascular Registry.

Data synthesis A hybrid decision tree and Markov model was developed to simulate the short term and long term effects of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm compared with no systematic screening on clinical and cost effectiveness outcomes. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses using Monte Carlo simulation were carried out. Results were presented in a cost effectiveness acceptability curve, an expected value of perfect information curve, and a curve showing the expected (net) number of avoided deaths from abdominal aortic aneurysm over time after the introduction of screening. The model was validated by calibrating base case health outcomes and expected activity levels against evidence from the recent Cochrane review of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Results The estimated costs per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained discounted at 3% per year over a lifetime for costs and QALYs was £43 485 (€54 852; $71 160). At a willingness to pay threshold of £30 000 the probability of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm being cost effective was less than 30%. One way sensitivity analyses showed the incremental cost effectiveness ratio varying from £32 640 to £66 001 per QALY.

Conclusion Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm does not seem to be cost effective. Further research is needed on long term quality of life outcomes and costs.

Introduction

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms are responsible for up to 2% of deaths among men aged 65 or more. Overall survival after ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm is 80-90%; about 40-50% of deaths occur before people reach hospital.1 2

Implementation of a national screening programme for abdominal aortic aneurysm in men is on the public health agenda of many western European countries. Screening programmes that establish diagnosis through ultrasonography and offer elective repair have been advocated because abdominal aortic aneurysms rarely give rise to symptoms and so are not diagnosed before they rupture. The scientific case for screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm seems established; there is evidence of benefit in men, with a significant reduction in related deaths.1

The cost effectiveness of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm may be acceptable, but further analysis is necessary.1 Within trial cost effectiveness reported in the Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS), the largest randomised trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm, after four years of follow-up was £28 400 per life year gained. The authors concluded that their result was at the margin of acceptability according to National Health Service thresholds but that cost effectiveness was expected to improve substantially over a longer period.3 The study did not, however, collect information on quality adjusted life years (QALYs) gained. Endovascular repair of aortic aneurysm was not used in the trial but is increasingly used in elective surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm, and the long term costs of unwanted side effects were not included.

Several health economic decision models of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm combining data from MASS and other randomised trials with other sources of evidence have been published.4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Inconsistencies in the inputs, structure, and results of the model, together with optimistic assumptions about mortality and quality of life after elective surgery, and a focus on short term clinical costs, have made the relevance of these models for decision making unclear. Accordingly, new research on cost effectiveness of screening is recommended.1 13 14

High external validity of a modelling approach could be achieved; ultrasonography is considered the ideal method for screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm and has been used in all trials of abdominal aortic aneurysm and decision analytical models. Initial ultrasound examination and surveillance of patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysms are managed by mobile teams of hospital specialists, and screening programmes are controlled by cardiovascular consultants in public hospitals.13 14 15 There are differences among countries in prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm,16 cost of emergency repair, and mortality rates for elective repair,13 but an appropriate modelling approach can account for such differences in detailed sensitivity analyses.17

We carried out cost effectiveness analyses of a screening programme for abdominal aortic aneurysm in men aged 65 on the basis of the development and evaluation of a probabilistic, enhanced economic decision analytical model from initial ultrasound examination to death. We applied evidence for the effectiveness of screening from MASS with long term empirical data on mortality after surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm from the Danish Vascular Registry. The study was done from a healthcare perspective to assure comparability with other studies, and in sensitivity analyses we included costs outside the healthcare sector.

Methods

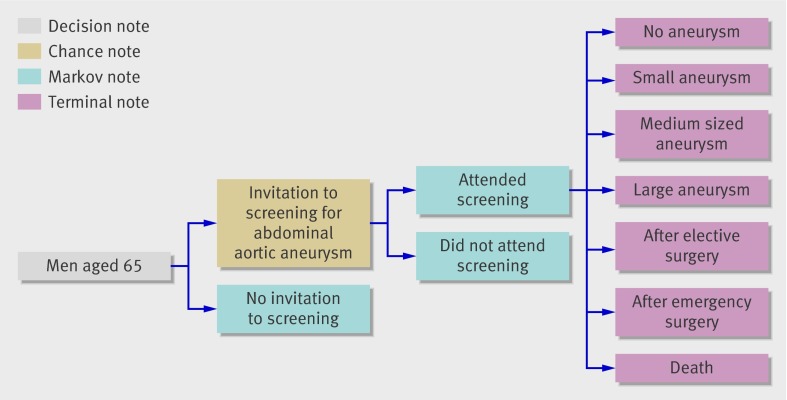

We modelled cost effectiveness by combining a decision tree with Markov modelling of long term consequences.18 The model portrayed a cohort of men aged 65 who could receive an invitation or not to participate in a hypothetical screening programme for abdominal aortic aneurysm—that is, incidental diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm (fig 1). We used standard decision analysis software (TreeAge Pro 2007; TreeAge Software, Williamstown, MA).

Fig 1 Decision analytical model of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm compared with no systematic screening

The hypothetical screening programme was carried out by a team of mobile ultrasound technicians in a community setting. The diameter of the aneurysm was measured and action determined according to the size: if the aneurysm was large (≥5.5 cm) the patient was referred for vascular surgical assessment, and if the aneurysm was small (3-4.4 cm) or medium sized (4.5-5.4 cm) the patient was rescanned regularly or until the aneurysm became large. Men with normal aorta were assumed to be without risk of rupture and were classified as having no abdominal aortic aneurysm until death.

In each successive cycle we applied a matrix of transitional probabilities to determine possible transitions from each stage. The risk of rupture depended on the size of the aneurysm—that is, state of health. Each year the men also had a risk of dying from other causes, depending on their age. We enhanced the model by relaxing the Markov assumption; memory was built into the model using time dependent probabilities of rupture according to an estimated age distribution of men aged 65 or more having emergency surgery. The cycle length was one year.

We made the model probabilistic by applying a relevant distribution for each variable in the model. To increase transparency and credibility we used normal distribution as a starting point for probabilities. As normal distribution was not appropriate in a simulation because there would be a non-negligible probability of sampling an impossible value, in this case a probability below zero, we therefore used the mean and standard deviation from normal distributions to approximate β distributions for binomial data and Dirichlet distributions for multinomial data. For costs we used “right tailed” γ distributions.18

To determine the value for the entire process (cost effectiveness ratio of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm) we calculated expected costs and health outcomes for the screening alternative compared with the non-screening alternative.

We chose Monte Carlo simulation sampling means as the preferred way of calculating expected values, which differ from simple roll back “expected values” based on the point or mean value for each variable. We used Monte Carlo simulations to select values at random from the specified distributions for model variables. We calculated expected costs and health outcomes for the two alternatives over second order uncertainties for a cohort of 10 000 hypothetical men aged 65.

Data input

The model was based on extensive and detailed datasets for all inputs (table 1). We obtained estimates of the variables required for the model through a systematic review of the literature.

Table 1.

Data inputs and assumptions in Markov model

| Variable | Mean | Distribution* | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability | |||

| Prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm ≥3 cm | 0.04 | Normal (α 0.04, σ 0.0051) | Lindholt et al19 |

| Acceptance rate | 0.77 | Normal (α 0.77, σ 0.0056) | Lindholt et al19 |

| Size of abdominal aortic aneurysm (initial probability): | |||

| Small (3-4.4 cm) | 0.71 | Normal (α 0.71, σ 0.056) | Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study Group3 |

| Medium (4.5-5.4 cm) | 0.17 | Normal (α 0.17, σ 0.026) | |

| Large (≥5.5 cm) | 0.12 | Normal (α 0.12, σ 0.051) | |

| Risk of rupture per year: | |||

| Small aneurysm | 0.003 | Normal (α 0.003, σ 0.0015) | Brown and Powel20 |

| Medium aneurysm | 0.015 | Normal (α 0.015, σ 0.0077) | |

| Large aneurysm | 0.065 | Normal (α 0.065, σ 0.03) | |

| Growth rate per year: | |||

| From small to medium | 0.115 | Normal (α 0.115, σ 0.005) | Henriksson and Lundgren,4 Silverstein et al5 |

| From medium to large | 0.159 | Normal (α 0.159, σ 0.006) | |

| 30 day mortality: | |||

| Elective surgery | 0.038 | Normal (α 0.038, σ 0.0051) | Danish Vascular Registry. Annual report for 200621 |

| Emergency surgery | 0.45 | Normal (α 0.45, σ 0.0143) | |

| Proportion of patients with large abdominal aortic aneurysm eligible for surgery | 0.814 | Normal (α 0.814, σ 0.0256) | Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study Group3 |

| Proportion of ruptures where patient reaches hospital alive | 0.401 | Normal (α 0.401, σ 0.051) | Henriksson and Lundgren,4 Silverstein et al5 |

| Ad hoc diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm | 0.06 | Normal (α 0.06, σ 0.0255) | Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study Group3 |

| Cost (£) | |||

| Elective surgery | 10 663 | γ (α 86.17, λ 0.0071) | Danish DRG casemix system22 |

| Emergency surgery | 12 125 | γ (α 93.49, λ 0.0088) | Danish DRG casemix system 22 |

| Surgery with death occurring within 30 days | 5 038 | γ (α 28.5, λ 0.0057) | Danish DRG casemix system22 |

| Cost per invitation | 6 | — | Henriksson and Lundgren4 |

| Cost per ultrasound examination | 39 | — | Henriksson and Lundgren4 |

£1.00 (DKK 9.41; $1.78; €1.26).

*Mean and standard deviation from normal distributions are used to approximate β and Dirichlet distributions for simulation purposes.

Standard survival analyses were based on Danish data on long term mortality after elective surgery and emergency surgery. We obtained data on incident cases of abdominal aortic aneurysm from the Danish Vascular Registry for the period 1996-2006 and linked with data on vital status from the Danish Central Office of Civil Registration.23 From the Danish Vascular Registry we obtained national data on the age distribution of men having emergency surgery during 1996-2006.

We used quality of life weights from a standard population of men—that is, a QALY weight of 0.80 for all hypothetical men aged 65-70 and 0.76 for those aged more than 70. In a sensitivity analysis we used age adjusted quality of life weights from average male smokers of 0.71, and 0.67 for men aged 65-70 and those aged more than 70.24

Costs were in 2007 prices (DKK 9.41; £1.00; €1.26; $1.78); we applied the cost to the Danish healthcare system (DRG) for 2007 as best estimate for surgery cost.22 Surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm in the Danish DRG system comprises three groups: surgery, emergency surgery, and surgery with death occurring within 30 days.

Data from the recent Cochrane review of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm were used as independent calibration data for validation of the model.1 We applied tracker variables to the model, and we calculated the expected number of avoided deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm and levels of surgery and surveillance under the two alternatives and compared them with Cochrane data. We calculated the average age at death from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm in the different patient pathways and calibrated this against registry data and published data.

Analyses

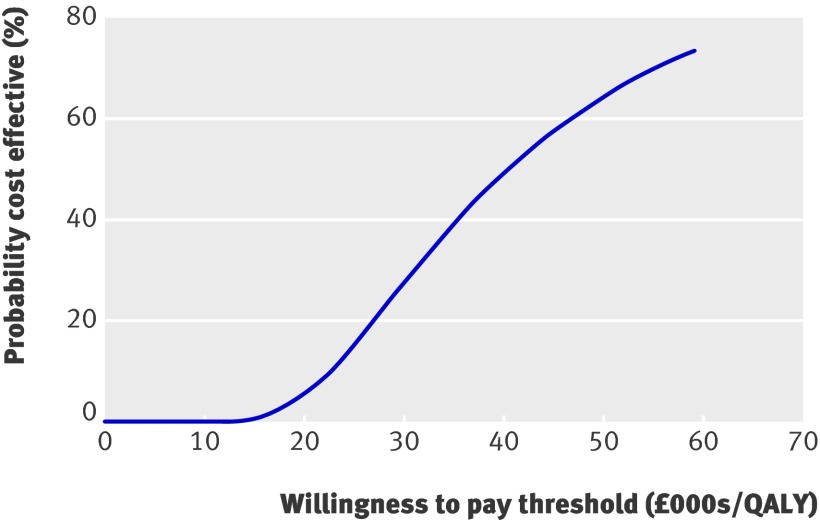

We presented simulation output in a cost effectiveness acceptability curve for screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm, showing the probability of screening being cost effective at different threshold ratios.18

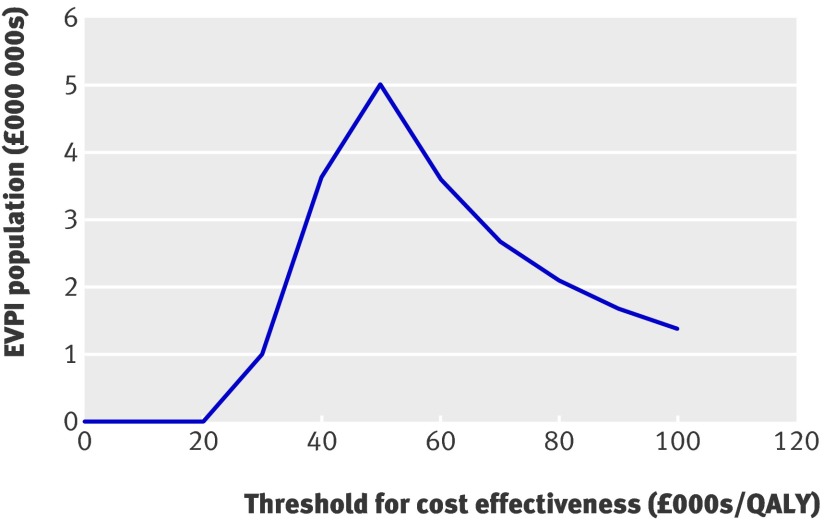

For the same Monte Carlo simulation used to construct the cost effectiveness acceptability curve we further calculated the expected cost of uncertainty (expected value of perfect information surrounding the decision). We presented the expected value of perfect information for a hypothetical population of 250 000 men aged 65. This value illustrates the opportunity cost of making the incorrect decision, calculated as the difference between the expected net benefit with perfect information and the expected net benefit with current information. The expected value of perfect information provides a basis for deciding whether or not to invest in further research to reduce variable uncertainty.18

We carried out one way sensitivity analyses of all model variables and of several additional factors likely to influence cost effectiveness.25 The credible range in variable estimates was found by a search of the literature. We included the private cost of transportation; the unit cost of transportation was £0.36/0.62 miles (1 km) and we assumed 20 km to be the average distance to and from the screening location, in total £14.00 per individual. Indirect costs were included assuming that three hours were spent per screening test, that 37% of all men aged 65 were employed, and that an average salary as an estimate of the value of lost productivity corresponded to £15.90 per attendee. We discounted cost and effect at 3% to express net present values. Alternative values (0% and 5%) were applied in sensitivity analyses.

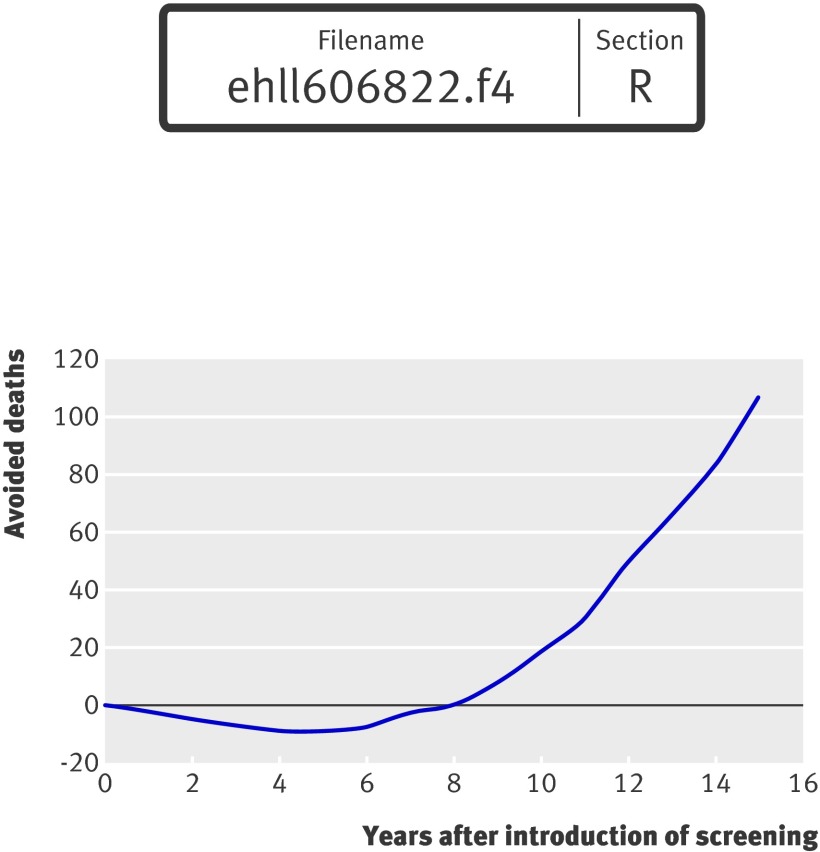

We simulated consecutive cohorts of men aged 65 by summing up expected numbers of deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm and surgical activity to illustrate the dynamics of the screening programme. This was done using two dimensional Monte Carlo simulations averaging 10 000 second order samples of variable values with 10 000 trials (random walks) for each variable sample. This allowed for uncertainty of variables and variability. To illustrate the development in the expected (net) number of avoided deaths over time as a result of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm we created curves for the first 15 years of consecutive cohorts of 10 000 men aged 65 at the time of screening. We compared the results of simulating five years of screening with that of a single cohort followed throughout life.

Results

At a discounted rate of 3% the incremental cost effectiveness ratio (base case) was £43 485 per QALY (table 2). The incremental cost effectiveness ratio with one way sensitivity analyses was £32 640-£66 001 per QALY (table 2).

Table 2.

Incremental cost effectiveness ratio (base case) and selected one way sensitivity analyses of screening men aged 65 for abdominal aortic aneurysm

| Scenario | £/QALY |

|---|---|

| Base case | |

| Prevalence: | 43 485 |

| 2% | 57 169 |

| 3% | 48 049 |

| 5% | 40 742 |

| Probability of reaching hospital alive with rupture: | |

| Low (30%) | 32 640 |

| High (50%) | 66 001 |

| 30 day mortality after elective surgery: | |

| Low (2.5%) | 36 128 |

| High (5%) | 54 808 |

| Incidental screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: | |

| Low (5% per year) | 45 366 |

| High (7% per year) | 42 018 |

| Acceptance: | |

| Low (60%) | 43 920 |

| High (80%) | 43 163 |

| Proportion of aneurysms >5.5 cm: | |

| Low (8%) | 52 785 |

| High (16%) | 37 571 |

| Discount rate: | |

| Low (0%) | 47 334 |

| High (5%) | 46 478 |

| Proportion eligible for elective repair: | |

| Low (−10%) | 45 508 |

| High (+10%) | 42 372 |

| Cost of emergency surgery: | |

| Low (−25%) | 43 855 |

| High (+25%) | 43 115 |

| Cost of elective repair: | |

| Low (−25%) | 39 877 |

| High (+25%) | 47 140 |

| Cost of surgery with death occurring within 30 days: | |

| Low (−25%) | 44 595 |

| High (+25%) | 42 421 |

| Cost of invitation: | |

| Low (−50%) | 42 236 |

| High (+50% ) | 44 919 |

| Cost of ultrasound examination: | |

| Low (−50%) | 36 731 |

| High (+50%) | 50 470 |

| QALY weights: | |

| Low (−10%) | 48 308 |

| High (+10%) | 42 372 |

| As average smokers24 | 49 412 |

| Including costs of endovascular repair of aortic aneurysm in 25% of elective repairs26 | 56 623 |

| Including cost of future health care of smokers27 | 48 527 |

| Including cost of patient transport and indirect cost | 54 403 |

Figure 2 presents the Monte Carlo second order calculation of 10 000 hypothetical men aged 65. At a willingness to pay threshold of £30 000 the probability of screening being cost effective was less than 30%.

Fig 2 Cost effectiveness acceptability curve of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in hypothetical population of 10 000 men aged 65

Figure 3 presents the expected value of perfect information for a hypothetical population of 250 000 men aged 65. It would be potentially cost effective to carry out further research if the expected value of perfect information for this population exceeded the expected costs of additional research. If, for instance, additional research was expected to cost £1m, then such research would be potentially cost effective if the threshold was greater than £30 000.

Fig 3 Expected value of perfect information (EVPI) for hypothetical population of 250 000 men aged 65

The expected value of perfect information should be expressed for the total population of current and future men who will benefit from the health technology. Assuming that screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm for the next 20 years will be offered to at least 250 000 men aged 65 each year in England the expected value of perfect information for this total population will be roughly the expected value of perfect information×20 (undiscounted) or the expected value of perfect information×14.9 (discounted), where 14.9 is the annuity factor for a period of 20 years with an interest rate of 3%. For even larger (international) populations the curve will be shifted further upward, suggesting that it more likely will be considered cost effective to achieve better information. This reflects that research knowledge has so called public good characteristics.18

The results of the model simulation of a cohort of 10 000 men followed through life were consistent with those from published randomised trials (table 3).1 3 Assuming about 250 000-300 000 men aged 65 in England were followed, an expected 675-810 deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm would be avoided which is similar to the present expectancy of the NHS. Other simulation results for the non-screening alternative—for example, estimated mean age at rupture (74 years), mean age at death due to rupture (75 years), and mean age at death after elective surgery without screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (71 years), were consistent with published data.28 29

Table 3.

Expected level of activity in men aged 65 with or without screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm

| Variable | Single cohort of men aged 65 (lifetime perspective) | Difference | Five consecutive cohorts of men aged 65 (5 year accumulated) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of men invited | 10 000 | — | 50 000 | — |

| No of attendees (No of ultrasound examinations) | 6670 | — | 26 680 | — |

| No of patients screened: | ||||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm identified | 267 | — | 1067 | — |

| Under surveillance* | 240 | — | 903 | — |

| No of elective operations: | ||||

| With screening | 151 | 96 | 238 | 196 |

| Without screening | 55 | 42 | ||

| No of deaths after elective surgery†: | ||||

| With screening | 12 | 8 | 18 | 15 |

| Without screening | 4 | 3 | ||

| No of deaths after emergency surgery‡: | ||||

| With screening | 47 | −35 | 30 | −7 |

| Without screening | 82 | 37 | ||

| Total No of deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm: | ||||

| With screening | 59 | −27 | 49 | 9 |

| Without screening | 86 | 40 |

*Individuals with an identified abdominal aortic aneurysm who cannot be offered elective surgery because of contraindications.

†Counted as one year mortality (which amounts to about double the 30 day mortality). Number of deaths with screening includes non-attendees.

‡Counted as one year mortality. The average age at death from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm is estimated to be about 75 years in model without screening.

The expected result five years after the introduction of screening (that is, five consecutive cohorts of 10 000 men aged 65) shows an increase of nine total number of deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm as a side effect of the increased number of elective operations in the short term (which is an increase of more than fourfold in the first five years).

Figure 4 illustrates the (net) number of avoided deaths over time after the introduction of screening for men aged 65. The curve shows an increase in deaths in the first eight years, assuming that eight successive cohorts of 10 000 men aged 65 were screened. This curve illustrates the time lag between implementation of and the realisation of future benefits from screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Fig 4 Simulation of expected (net) number of avoided deaths from abdominal aortic aneurysm after screening 15 consecutive cohorts of 10 000 men aged 65. Expected (net) number of avoided deaths are calculated as the difference in total expected number of deaths due to ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm and deaths due to elective surgery under the two alternatives

Discussion

We constructed a decision analytical model to evaluate the cost effectiveness of screening men aged 65 for abdominal aortic aneurysm. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio (base case) was £43 485 per QALY. At a willingness to pay threshold of £30 000 the probability of screening being cost effective was less than 30%. One way sensitivity analyses showed the incremental cost effectiveness ratio varying from £32 640 to £66 001 per QALY. A screening programme was therefore unlikely to be cost effective.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our decision analytical framework was based on best evidence of effectiveness and costs, including registry data for long term mortality after elective and emergency repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm, and age distribution of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. The Danish Vascular Registry has been shown to have a high degree of validity.30

We validated the model by calibrating against key values from the Cochrane review of effectiveness of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm.1 The number of avoided deaths, amount of elective and emergency surgery, and mean age at surgery were consistent with pooled data from randomised trials and clinical data. Estimated age at rupture, at death due to rupture, and at death after elective surgery in the non-screening alternative were also consistent with published data.

Decision analytical models provide several advantages compared with economic evaluations alongside clinical trials; evidence from multiple sources can be combined and systematic sensitivity analyses done.18 23 None of the randomised trials of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm collected information on QALY gains and long term costs; endovascular repair of aortic aneurysm was not used in the trials and accordingly not included in the cost calculations in published health economic studies of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Aortic stents are increasingly used in many vascular departments in western European countries. Endovascular repair may be cost effective in patients who are unfit for open repair, but it is used increasingly as a substitute for conventional open repair.26 Sensitivity analyses showed that including the cost of graft surveillance and secondary procedures after endovascular repair significantly increased the cost per QALY gained from screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm.

One limitation of our modelling approach was that it relies on a combination of data from studies in different countries, gross costing, and average QALY weights.17 18 25 Another limitation was the focus on screening all men aged 65. We did consider doing similar analyses in high risk groups such as smokers but the data were unavailable.

Comparison with other studies

Our estimate of the incremental cost effectiveness ratio is comparable to the within trial cost effectiveness ratio reported in MASS of £28 400 per life year gained (equivalent to about £36 000 per QALY).3 The main difference is in the timing of the expected health gains. The results in MASS were presented as a weighted average for the entire group of men aged 65-74, which is not the same as screening men aged 65. A lower incremental cost effectiveness ratio was therefore reported in that study. Other reasons are differences in the cost of elective and emergency surgery and the application of different discount rates for costs and health outcomes in MASS.3

Our estimate is not comparable with previous modelling studies, which in general claim that screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm is cost effective.4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 We believe our study provides a more realistic estimate of cost effectiveness. For instance, previous studies did not use enhanced Markov models with time dependency built into the transitional probabilities, nor could they provide solid evidence of model validity.13 14

Implications

This study does not support the widespread conception that screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm is cheap. Ultrasonography may be cheap on a per person basis, but screening is not just a test but a programme with several interdependent activities. If screening is to be effective then overall administration of the programme, operational planning, a communication strategy, a quality assurance system, and more are needed. To carry out systematic testing of a large population, several screening locations and arrangements for transportation are required to gain wider geographical coverage. Equally importantly, ultrasonography leads to a large number of patients unfit for surgery with a need for continued observation under care of a vascular surgeon.

Further research

According to the expected value of perfect information in fig 3, additional research may be cost effective. Uncertainty surrounds several key variables, with the risk that a wrong decision might be made.

Firstly, we assumed in accordance with earlier health economic studies that patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm could return to a quality of life comparable to the average population: there is only poor evidence for this assumption.2 None of the randomised trials on abdominal aortic aneurysm systematically measured QALY gains, so we cannot be sure that screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm provides the expected QALY gains. More than 90% of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm have a history of smoking, and assuming that all patients gain a quality of life after aneurysm repair comparable to the average age matched population seems to conflict with public health evidence that smokers experience a lower quality of life in their remaining years.24 27 Secondly, no study has determined the long term healthcare cost after hospital discharge for elective repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. This includes long term care after major surgical complications such as stroke, chronic renal failure, major amputation, and cardiac infarctions, which occur in 1-5% of patients after elective surgery.6 Thus these costs might be high if a screening programme for abdominal aortic aneurysm is implemented. Thirdly, since the late 1990s considerable interest has been shown in smoking cessation programmes. The effect of national antismoking laws and campaigns for smoking cessation and the increase in ad hoc detection of abdominal aortic aneurysm cases as imaging becomes more widely utilised for other reasons, may reduce the prevalent pool of undiagnosed abdominal aortic aneurysms and hence the effectiveness of screening.

Noticeably, table 2 shows the incremental cost effectiveness ratio to be quite insensitive to one way changes in variable values—that is, even large changes in variable values do not change the conclusion. The most influential variable seems to be the probability of reaching hospital alive in case of rupture. This robustness of the result points to the need for further research on alternatives to mass screening.

Conclusion

Screening men aged 65 for abdominal aortic aneurysm was not cost effective; the incremental cost effectiveness ratio was £43 485 per QALY (range £32 640-£66 001 per QALY). At a willingness to pay threshold of £30 000 per QALY the probability of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm being cost effective was less than 30%. The expected value of perfect information analysis suggests that additional research is needed.

What is already known on this topic

One time ultrasound screening of men aged 65 or more can significantly reduce mortality from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

It is uncertain whether screening all 65 year old men is cost effective

What this study adds

Screening men aged 65 for abdominal aortic aneurysm was not cost effective

The incremental cost effectiveness ratio was £43 485 per QALY (range £32 640-£66 001 per QALY)

At a willingness to pay threshold of £30 000 per QALY there was a less than 30% probability of screening being cost effective

Contributors: LE carried out the main study and drafted the manuscript. JS, KO, SC, MB, and MK participated in the analyses and discussion of results. LE, KO, and SC carried out the literature search and selection of data input in the model. All authors approved the final manuscript and are guarantors.

Funding: Centre for Public Health, Central Denmark Region.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b2243

References

- 1.Cosford PA, Leng GC. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):CD002945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medical Advisory Secretariat, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ultrasound screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ontario: Health Technology Policy Assessment, 2005.

- 3.Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study Group. Multicentre aneurysm screening study (MASS): cost effectiveness analysis of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms based on four year results from randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002;325:1135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henriksson M, Lundgren F. Decision-analytical model with lifetime estimation of costs and health outcomes for one-time screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in 65-year-old men. Br J Surg 2005;92:976-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverstein MD, Pitts SR, Chaikof EL, Ballard DJ. Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA): cost-effectiveness of screening, surveillance of intermediate-sized AAA, and management of symptomatic AAA. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2005;18:345-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee TY, Korn P, Heller JA, Kilaru S, Beavers FP, Bush HL, et al. The cost-effectiveness of a “quick-screen” program for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Surgery 2002;132:399-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim LG, Thompson SG, Briggs AH, Buxton MJ, Campbell HE. How cost-effective is screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms? J Med Screen 2007;14:42-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wanheinen A, Lundkvist J, Bergquist D, Björck M. Cost-effectiveness of different screening strategies for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2005;41:741-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pentikäinen TJ, Sipilä T, Rissanen P, Soisason-Soininen J, Salo J. Cost-effectiveness of targeted screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2000;16:22-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connelly JB, Hill GB, Millar WJ. The detection and management of abdominal aortic aneurysm: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Clin Invest Med 2002;25:127-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boll APM, Severens JL, Verbeek ALM, Vliet JA. Mass screening on abdominal aortic aneurysm in men aged 60 to 65 in the Netherlands. Impact on life expectancy and cost-effectiveness using a Markov model. Eur J Vasc Surg 2003;26:76-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soisalon-Soininen S, Rissanen P, Pentikäinen T, Mattila T, Salo JA. Cost-effectiveness of screening for familial abdominal aortic aneurysms. VASA 2001;30:262-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell HE, Briggs AH, Buxton MJ, Kim LG, Thompson SG. The credibility of health economic models for health policy decision-making: the case of population screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:11-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehlers L, Sørensen J, Jensen LG, Bech M, Kjølby M. Is population screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm cost-effective? BMC Cardiovasc Dis 2008;8:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergqvist D, Björk M, Wanhainen A. Abdominal aortic aneurysm—to screen or not to screen. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;35:13-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornuz J, Pinto CS, Tevaerai H, Egger M. Risk factors for asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Public Health 2004;14:343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drummond M, Manca A, Sculpher M. Increasing the generalizability of economic evaluations: recommendations for the design, analysis, and reporting of studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21:165-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briggs A, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- 19.Lindholt JS, Juul S, Fasting H, Henneberg EW. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms: single centre randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;330:750-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown LC, Powel JT. UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Risk factors for aneurysm rupture in patients kept under ultrasound surveillance. Ann Surg 1999;230:289-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danish Vascular Registry. Annual report for 2006. www.karbase.dk.

- 22.Danish DRG casemix system. 2007. www.sst.dk.

- 23.StatBank Denmark. Summary vital statistics 2005. www.statistikbanken.dk.

- 24.Kaper J, Wagene EJ, Schayck CP, Severens JL. Encouraging smokers to quit. The cost effectiveness of reimbursing the costs of smoking cessation treatment. Pharmacoeconomics 2006;24:453-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drummond M, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brian B, Stoddart GL. Methods for the evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed. Oxford: Medical Publications, 2005.

- 26.Michaels JA, Drury D, Thomas SM. Cost-effectiveness of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Br J Surg 2005;92:960-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen SR, Prescott E, Sørensen T, Søgaard J. The total lifetime costs of smoking. Eur J Public Health 2004;14:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lovegrowe RE, Javid M, Magee TR, Galland RB. A meta-analysis of 21 178 patients undergoing open or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 2008;95:677-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cronenwett JL, Likosky DS, Russel MT, Eldrup-Jørgensen J, Stanley AC, Nolan BW. A regional registry for quality assurance and improvement: the vascular study group of Northern New England (VSGNNE). J Vasc Surg 2007;46:1093-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laustsen J, Jensen LP, Hansen AK. Accuracy of clinical data in a population based vascular registry. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2004;27:216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]