Abstract

Objective To determine the effectiveness of increasing the dietary content of soluble fibre (psyllium) or insoluble fibre (bran) in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting General practice.

Participants 275 patients aged 18-65 years with irritable bowel syndrome.

Interventions 12 weeks of treatment with 10 g psyllium (n=85), 10 g bran (n=97), or 10 g placebo (rice flour) (n=93).

Main outcome measures The primary end point was adequate symptom relief during at least two weeks in the previous month, analysed after one, two, and three months of treatment to assess both short term and sustained effectiveness. Secondary end points included irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity score, severity of abdominal pain, and irritable bowel syndrome quality of life scale.

Results The proportion of responders was significantly greater in the psyllium group than in the placebo group during the first month (57% v 35%; relative risk 1.60, 95% confidence interval 1.13 to 2.26) and the second month of treatment (59% v 41%; 1.44, 1.02 to 2.06). Bran was more effective than placebo during the third month of treatment only (57% v 32%; 1.70, 1.12 to 2.57), but this was not statistically significant in the worst case analysis (1.45, 0.97 to 2.16). After three months of treatment, symptom severity in the psyllium group was reduced by 90 points, compared with 49 points in the placebo group (P=0.03) and 58 points in the bran group (P=0.61 versus placebo). No differences were found with respect to quality of life. Fifty four (64%) of the patients allocated to psyllium, 54 (56%) in the bran group, and 56 (60%) in the placebo group completed the three month treatment period. Early dropout was most common in the bran group; the main reason was that the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome worsened.

Conclusions Psyllium offers benefits in patients with irritable bowel syndrome in primary care.

Trial registration Clinical trials NCT00189033.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder characterised by recurrent episodes of abdominal pain or discomfort associated with an altered bowel habit, not explained by any structural or biochemical changes in the gut.1 The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in the population is in the order of 10%, and approximately a quarter of people with irritable bowel syndrome symptoms seek medical advice.2

Most studies report a female predominance, and the reported incidence of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care is 4-13 per 1000 patients per year, less than 5% of whom are referred to hospital.3 Irritable bowel syndrome is a chronic recurrent condition with relapsing symptoms in more than half of patients.4 It should not be diagnosed by exclusion but rather as a “positive” diagnosis. Diagnostic tools such as the Rome criteria have been developed to facilitate this. The Rome criteria are primarily designed for research purposes, and their validity in clinical primary care is not well established; most general practitioners do not use them.5 6 7 8

In the management of irritable bowel syndrome, dietary advice is often given. Most general practitioners recommend an increase in the fibre content of the daily diet, through the addition of insoluble fibre in the form of bran.9 Furthermore, approximately half of patients with irritable bowel syndrome receive drug treatment, often including psyllium based supplements.10 However, pooled analyses show limited evidence that fibre actually alleviates symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, and insoluble fibre may even worsen the symptoms.11 12 13 Most available studies on fibre treatment have severe methodological limitations, such as inadequate outcome assessment and lack of placebo control, and all trials were done in secondary care. In contrast, most patients with irritable bowel syndrome are treated in primary care, and this patient group may benefit more from fibre treatment than do those in secondary care.3 9 14 15

We did a randomised placebo controlled trial in primary care patients with irritable bowel syndrome to assess the effectiveness of treatment with either psyllium or bran on symptoms and quality of life.

Methods

Setting and participants

We recruited patients in the practices of the Utrecht and Maastricht primary care research networks. General practitioners in both networks have vast experience in participating in clinical trials in primary care. Patients aged between 18 and 65 years who had been diagnosed as having irritable bowel syndrome in the previous two years were selected from the medical electronic files of the participating practices by using the international classification of health problems in primary care (ICPC) code D93 (irritable bowel syndrome) or the text words “IBS” or “spastic colon.”16 The selected patients received an invitation signed by their general practitioner to participate in the trial. Non-responding patients received one reminder. In addition to these “prevalent” irritable bowel syndrome patients, patients consulting their general practitioner with new onset irritable bowel syndrome during the inclusion period (“incident” irritable bowel syndrome patients) were also invited to participate.

Patients with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome during the previous four weeks with either “definite” irritable bowel syndrome according to the Rome II diagnostic criteria or “probable” irritable bowel syndrome pragmatically diagnosed by their general practitioner were eligible for inclusion.1 17 The box shows the Rome II criteria and the more pragmatic definition of irritable bowel syndrome used in primary care in the Netherlands. Patients initially diagnosed as having irritable bowel syndrome but found to have organic bowel disease in follow-up (for example, colon cancer, coeliac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease), patients who had used fibre treatment in the previous four weeks, those with severe psychosocial disturbance and psychiatric disorders (panic disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, and mood disorder), those under specialist treatment for irritable bowel syndrome in the previous two years, and those who did not understand the Dutch language were excluded. All patients gave written informed consent. The inclusion period lasted from April 2004 to October 2006.

Definitions of irritable bowel syndrome

Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome1

-

At least 12 consecutive weeks of abdominal discomfort or pain in the preceding 12 months, with at least two of the following features:

Relieved with defecation

Onset associated with change in stool frequency

Onset associated with change in stool consistency

In the absence of structural or metabolic abnormalities to explain the symptoms

Pragmatic definition of irritable bowel syndrome17

Chronic gastrointestinal disorder characterised by recurrence of abdominal pain or bloating in relation to disturbed bowel habits, for at least four weeks

Mucus without blood in the stools, the presence of a palpable tender colon, and discomfort during rectal examination have been proposed to support the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome

In the absence of alarm symptoms (weight loss, rectal bleeding, nocturnal symptoms, or anaemia)

Randomisation

Patients were randomly allocated to one of two active treatment groups or placebo by means of a procedure using six block random number tables. The pharmacy of the University Medical Center Utrecht produced the randomisation list. The practice nurse determined the treatment allocation by drawing a sealed non-opaque envelope, which contained instructions on the type of trial treatment to be given to the patient. Randomisation was done after the baseline visit and after the patient agreed to participate and signed the informed consent. The nurses were strictly instructed to open the randomisation envelope only after the baseline visit at the general practitioners’ office.

Patients were randomly allocated to a 12 week treatment regimen with 10 g psyllium (soluble fibre), 10 g bran (insoluble fibre), or placebo (rice flour) in two daily dosages, to be taken with meals by mixing with food, preferably yoghurt. The average intake of dietary fibre in an adult Dutch population aged 25-65 years is estimated to be 24.0 (SD 6.9) g/day or 10.5 (2.6) g/4.18 MJ (1000 kcal). An addition of 10 g fibre to the diet (total dietary fibre content 30-40 g) is usually considered adequate.18 The practice nurse delivered the dietary supplements in identical containers at monthly study visits. The study was blinded at three levels (patient, doctor, and research personnel), but the practice nurse was aware of the treatment allocated. All participants were instructed not to change their dietary habits and to take sufficient fluids each day.

Outcomes measures

In line with previous recommendations for outcome assessment in research into functional gastrointestinal disease,19 20 we chose the adequate relief question (“Did you have adequate relief of irritable bowel syndrome related abdominal pain or discomfort in the past week?”) as the primary outcome. This instrument is a validated and generally accepted simple outcome assessment for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. We considered both short term relief of symptoms, particularly during periods of exacerbation of symptoms, and sustained, longer term effectiveness to be relevant in evaluating the effectiveness of fibre treatment. For this reason, we chose to evaluate effectiveness on a monthly basis and defined responders as those patients who reported adequate relief of symptoms during at least two out of the previous four weeks.21 We assessed this primary outcome after one, two, and three months of treatment. The patients were asked to keep a weekly diary during the 12 weeks of treatment and to measure adherence to treatment. We calculated the primary outcome from the weekly assessments, which were collected at the scheduled follow-up visits to the general practitioner one, two, and three months after the baseline visit.

Secondary outcome measurements included severity of symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, severity of abdominal pain, and quality of life. Severity of symptoms was assessed with the irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity score. This is a validated symptom score that uses visual analogue scales to relate five aspects of bowel dysfunction to the actual intensity of symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. The severity of abdominal pain was measured by means of the first question of this score.22 Disease specific quality of life was monitored with the irritable bowel syndrome quality of life scale, which comprises 30 items in nine subscales and has been validated in various populations.23 Fibre intake was monitored every month during the trial with a food frequency questionnaire including 78 items on fibre intake and 24 on fluid intake. The self administered questionnaire is validated for ranking participants according to intake of dietary fibre and was adapted from the EPIC food frequency questionnaire.24 25 The secondary outcomes were recorded during one, two, and three months. Adherence to the trial treatment was checked at every visit by scrutinising the patient’s diary. Adverse events were recorded from part B of the irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity scale.22 We considered patients to have side effects of moderate severity if they reported the symptoms for more than half of the time during the previous month.

As blinding is difficult in studies with fibre as the intervention, we asked patients, after completion of the trial, to guess which treatment they had received. We used a strict protocol for the follow-up of patients. We instructed the nurses to check the questionnaires for completeness at regular visits. Patients who did not attend were sent a written reminder and later contacted by telephone in case of persistent non-response.

Sample size

We considered a minimal difference of 20% in the proportion of responders on the adequate relief scale (that is, more than two weeks’ adequate relief in four weeks) between the active treatments and placebo to be clinically relevant. The placebo response was estimated at 40%.26 We thus needed 95 patients in each treatment arm to give the study 80% power with a type I error of 5%. We aimed to include 285 patients.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were based on the intention to treat principle. We calculated the proportion of responders in the three groups and compared them at one, two, and three months. Relative risks with 95% confidence intervals and risk differences with 95% confidence intervals compared with placebo were calculated. We made similar calculations after imputing missing values on the primary outcome, assuming that patients who did not fill in the adequate relief question in the diary were non-responders (“worst case analysis”). Changes in the secondary outcomes—irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity score, severity of abdominal pain, and irritable bowel syndrome quality of life at one, two, and three months after the baseline measurements—were also compared. We assessed stability of the treatment effect over time by using one factorial analysis of variance for repeated measures. To correct for possible differences in relevant baseline characteristics between the three groups, we did multiple logistic regression analyses. As prespecified in the study protocol, we did subgroup analyses of patients who fulfilled the Rome II irritable bowel syndrome diagnostic criteria and of those with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Results

Participants

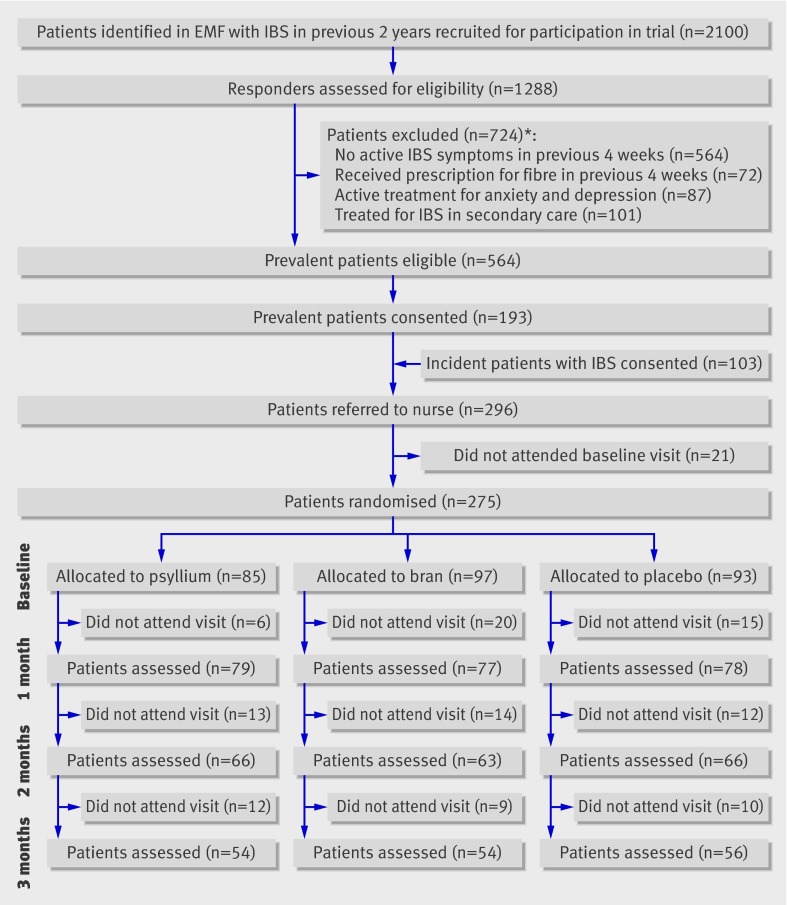

A total of 296 patients agreed to participate in the trial: 193 patients with “prevalent” irritable bowel syndrome and 103 with “incident” irritable bowel syndrome. For various reasons (second thoughts, non-eligibility, or no time), 21 patients did not attend the baseline visit. In total, 275 patients were randomised; 85 were allocated to psyllium, 97 to bran, and 93 to placebo (fig 1). Most of the patients were white (94%) and female (78%), and the mean age was 34.4 (SD 10.9) years. Irritable bowel syndrome had been diagnosed within the preceding two years in 25% of the patients, and 39% fulfilled the Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. More than half (56%) of the patients had constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome. The mean intake of dietary fibre before participation was 26.9 (SD 11.8) g/day, and patients used on average 2.4 (1.0) l/day of fluids. At baseline, patients allocated to psyllium reported less severe abdominal pain associated with irritable bowel syndrome than did those in the bran and placebo groups. The treatment groups did not differ with respect to other characteristics (table 1).

Fig 1 Flow chart of trial. No patients assigned to psyllium, bran, or placebo received different treatment. EMF=electronic medical file; IBS=irritable bowel syndrome. *Number exceeds 724 because more than one reason could be given

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Psyllium (n=85) | Bran (n=97) | Placebo (n=93) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 35 (10) (n=81) | 34 (12) (n=89) | 35 (18) (n=86) |

| Female | 64 (75) | 74 (76) | 77 (83) |

| White ethnicity | 79 (93) | 87/94 (93) | 84/87 (97) |

| Duration of symptoms (years): | (n=95) | (n=88) | |

| <2 | 19 (22) | 31 (33) | 17 (19) |

| 2-5 | 27 (32) | 24 (25) | 18 (21) |

| 6-10 | 13 (15) | 17 (18) | 18 (21) |

| >10 | 26 (31) | 23 (24) | 35 (40) |

| IBS according to Rome II criteria | 35 (41) | 39 (40) | 33 (36) |

| IBS subtype: | |||

| Constipation | 45 (53) | 56 (58) | 54 (58) |

| Diarrhoea | 25 (29) | 18 (19) | 25 (27) |

| Alternating | 15 (18) | 23 (24) | 14 (15) |

| IBS symptoms—mean (SD): | |||

| IBS symptom severity score (0-500) | 262 (68) (n=80) | 270 (77) (n=82) | 279 (70) (n=82) |

| Severity of abdominal pain (0-100) | 43 (29) (n=82) | 54 (32) (n=86) | 55 (37) (n=77) |

| IBS quality of life scale (0-100) | 72 (16) (n=77) | 74 (16) (n=83) | 74 (15) (n=79) |

| Dietary intake—mean (SD): | |||

| Fibre (g/day) | 28 (12) | 28 (15) (n=96) | 27 (15) (n=90) |

| Fluids (l/day) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.0) (n=96) | 2.4 (1.0) (n=91) |

IBS=irritable bowel syndrome.

Two hundred and thirty four (85%) patients attended the second visit at one month, 195 (71%) attended the visit at two months, and 164 (60%) attended the final visit at the end of the three month treatment period (fig 1). In total, 111 (40%) patients were lost to follow-up during the treatment period: 31 (36%) in the psyllium group, 43 (44%) in the bran group, and 37 (40%) in the placebo group. Reasons given were non-medical (such as moved to another city, n=15), presumed lack of benefit (n=10), symptom free (n=2), and intolerance of trial treatment (n=34; 7 patients allocated to psyllium, 18 patients allocated to bran, and 9 patients allocated to placebo). For the other patients, the reason for withdrawal was unknown (n=50). Patients who completed the trial and those lost to follow-up did not significantly differ with respect to demographic and disease specific characteristics (data not shown).

Primary outcome

Rates of response (that is, more than two weeks’ adequate relief per month) were significantly higher with psyllium than with placebo during the first month of treatment (45/79 (57%) v 27/78 (35%); relative risk 1.60, 95% confidence interval 1.13 to 2.26), with a risk difference of 22% (95% confidence interval 7% to 38%). The number needed to treat was four (that is, for every four patients who received psyllium, one reported at least two weeks’ adequate relief of abdominal pain or discomfort during one month of treatment). We saw a similar positive effect during the second month of treatment (39/66 (59%) v 27/66 (41%); relative risk 1.44, 1.02 to 2.06). During the third month of treatment the difference between psyllium and placebo—25/54 (46%) v 18/56 (32%)—was not statistically significant (relative risk 1.36, 0.90 to 2.04). Only in the third month of treatment was bran more effective than placebo (31/54 (57%) v 18/56 (32%); relative risk 1.70, 1.12 to 2.57) (table 2).

Table 2.

Adequate relief of abdominal pain or discomfort (at least two weeks every four weeks): intention to treat analysis

| Follow-up assessment and treatment | Responders (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | % treatment difference (95% CI) | Number needed to treat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | ||||

| Psyllium | 45/79 (57) | 1.60 (1.13 to 2.26) | 22 (7 to 38) | 4.5 |

| Bran | 31/77 (40) | 1.13 (0.81 to 1.58) | 5 (−10 to 21) | 16.7 |

| Placebo | 27/78 (35) | NA | NA | NA |

| Month 2 | ||||

| Psyllium | 39/66 (59) | 1.44 (1.02 to 2.06) | 18 (14 to 35) | 5.6 |

| Bran | 32/63 (51) | 1.22 (0.86 to 1.72) | 10 (−7 to 27) | 10.0 |

| Placebo | 27/66 (41) | NA | NA | NA |

| Month 3 | ||||

| Psyllium | 25/54 (46) | 1.36 (0.90 to 2.04) | 14 (−4 to 32) | 7.1 |

| Bran | 31/54 (57) | 1.70 (1.12 to 2.57) | 25 (7 to 43) | 4.0 |

| Placebo | 18/56 (32) | NA | NA | NA |

NA=not applicable.

At baseline, the three treatment groups were comparable with the exception of a somewhat lower severity of symptoms in the psyllium group. However, adjustment for baseline symptom severity in the multivariate logistic regression analysis only increased the observed beneficial effect—in the first month of treatment the relative risk for adequate relief in the psyllium group versus the placebo group was 2.70 (1.33 to 5.46). In the worst case analysis (considering patients lost to follow-up as non-responders), psyllium remained more effective than placebo during the first two months of treatment, but bran was no longer superior to placebo during the third month (1.45, 0.97 to 2.16) (table 3).

Table 3.

Adequate relief of abdominal pain or discomfort (at least two weeks every four weeks): intention to treat analysis with imputation of missing data as non-responders (worst case analysis)

| Follow-up assessment and treatment | Responders (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | % treatment difference (95% CI) | Number needed to treat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | ||||

| Psyllium | 45/85 (53) | 1.66 (1.19 to 2.31) | 24 (10 to 38) | 4.2 |

| Bran | 31/97 (32) | 1.07 (0.78 to 1.49) | 3 (−10 to 16) | 33.3 |

| Placebo | 27/93 (29) | NA | NA | NA |

| Month 2 | ||||

| Psyllium | 39/85 (46) | 1.44 (1.04 to 2.00) | 17 (3 to 31) | 5.9 |

| Bran | 32/97 (33) | 1.10 (0.80 to 1.53) | 4 (−9 to 17) | 25.0 |

| Placebo | 27/93 (29) | NA | NA | NA |

| Month 3 | ||||

| Psyllium | 25/85 (29) | 1.32 (0.91 to 1.95) | 10 (−3 to 23) | 10.0 |

| Bran | 31/97 (32) | 1.45 (0.97 to 2.16) | 13 (0.3 to 25) | 7.7 |

| Placebo | 18/93 (19) | NA | NA | NA |

NA=not applicable.

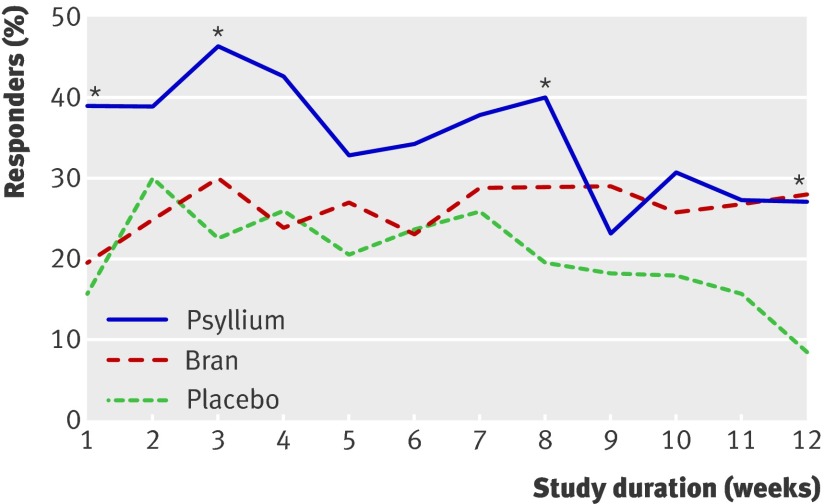

Analysis restricted to patients who fulfilled the Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome showed larger responder rates for psyllium compared with placebo—relative risk during the first month 1.81 (1.12 to 2.94) compared with 1.60 (1.13 to 2.26) for all patients with irritable bowel syndrome. A subgroup analysis of patients with constipation dominated irritable bowel syndrome showed comparable results—during the first month of treatment psyllium was better than placebo (1.65, 1.05 to 2.62). Figure 2 shows the proportion of patients in each group with adequate relief each week.

Fig 2 Proportion of patients with adequate relief of symptoms each week (intention to treat analysis). *P<0.05

Secondary outcomes

The reduction in severity of symptoms in the psyllium group was higher than that in the placebo group, with a significant mean reduction of 90 versus 49 points (P=0.03) only after three months of treatment, whereas the change in severity of symptoms in the bran group was comparable to that in the placebo group. We found no significant differences between the three groups with respect to changes in the severity of abdominal pain related to irritable bowel syndrome or in quality of life (table 4).

Table 4.

Absolute and relative change in severity of symptoms, severity of abdominal pain, and quality of life from baseline by one, two, and three months of treatment

| Follow-up assessment and treatment | IBS symptom severity score (0-500) | Abdominal pain score (0-100) | IBS quality of life scale (0-100) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | % | P value | Mean | % | P value | Mean | % | P value | |

| Month 1 | |||||||||

| Psyllium | −69 | 26 | 0.19 | −8 | 19 | 0.95 | 5 | 7 | 0.95 |

| Bran | −61 | 22 | 0.47 | −12 | 23 | 0.61 | 4 | 5 | 0.93 |

| Placebo | −49 | 18 | NA | −9 | 15 | NA | 3 | 4 | NA |

| Month 2 | |||||||||

| Psyllium | −69 | 26 | 0.92 | −10 | 24 | 0.58 | 6 | 8 | 0.58 |

| Bran | −53 | 20 | 0.32 | −11 | 20 | 0.63 | 5 | 7 | 0.85 |

| Placebo | −71 | 25 | NA | −14 | 26 | NA | 5 | 7 | NA |

| Month 3 | |||||||||

| Psyllium | −90 | 34 | 0.03 | −14 | 32 | 0.79 | 7 | 10 | 0.79 |

| Bran | −58 | 22 | 0.61 | −12 | 21 | 0.98 | 4 | 5 | 0.07 |

| Placebo | −49 | 18 | NA | −12 | 21 | NA | 4 | 6 | NA |

IBS=irritable bowel syndrome; NA=not applicable.

Adherence

Adherence to the trial treatment did not differ between the psyllium and bran groups. Patients allocated to psyllium added on average 7.1 (SD 3.1) g/day, bringing their total intake of dietary fibre to 35.1 (14.9) g/day. Patients allocated to bran added on average 6.5 (3.3) g/day and consumed 34.1 (17.2) g/day dietary fibre in total. The fibre intake in the daily diet, as monitored with the food frequency questionnaire, did not change during the treatment period. Total fluid intake, on average 2.5 (SD 0.8) l/day, did not differ between the groups.

Adverse events

Sixty three (74%) of 85 patients in the psyllium group, 62/97 (64%) patients in the bran group, and 61/93 (66%) patients in the placebo group reported at least one adverse event of moderate severity during the study (table 5). Diarrhoea and constipation were the most commonly reported adverse events. The proportions of patients with diarrhoea and constipation in the psyllium and bran groups were comparable to those in the placebo group. Severe constipation was reported in one patient treated with bran. No serious adverse events were reported during the study.

Table 5.

Most frequent adverse effects of moderate severity, regardless of relation to study treatment. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Adverse event | Psyllium (n=85) | Bran (n=97) | Placebo (n=94) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoea | 50/81 (62) | 59/94 (63) | 62/87 (71) | 0.35 |

| Constipation | 51/82 (62) | 53/92 (58) | 59/85 (69) | 0.26 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 12 (14) | 20/94 (21) | 18/92 (20) | 0.46 |

| Dysphagia | 9 (11) | 17/95 (18) | 12/92 (13) | 0.35 |

| Backache | 41 (48) | 41/95 (43) | 40/91 (44) | 0.63 |

| Headache | 28 (33) | 36/95 (38) | 29/92 (32) | 0.75 |

| Fatigue | 30 (35) | 35/95 (37) | 34/90 (38) | 0.96 |

| Flatulence | 59/83 (71) | 68/91 (75) | 70/90 (78) | 0.60 |

| Heartburn | 23/83 (28) | 26/91 (29) | 22/90 (24) | 0.81 |

| Lower urinary tract symptoms | 33/83 (40) | 46/91 (51) | 39/90 (43) | 0.34 |

| Pelvic pain | 9/83 (11) | 15/90 (17) | 18/90 (20) | 0.25 |

| Muscle or joint pain | 38/83 (46) | 37/91 (41) | 42/89 (47) | 0.65 |

Discussion

In this randomised trial in primary care patients with irritable bowel syndrome, psyllium resulted in a significantly greater proportion of patients reporting adequate relief of symptoms compared with placebo supplementation. Patients receiving psyllium also reported a significant reduction in severity of symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. We found no differences between the treatment groups in abdominal pain or health related quality of life. Bran showed no clinically relevant benefit, and many patients seemed not to tolerate bran.

Potential limitations

The selection process may have affected the generalisability of the results. A detailed comparison of randomised patients with eligible but non-randomised patients with irritable bowel syndrome (n=371) and non-eligible patients with irritable bowel syndrome (n=724) is reported elsewhere and showed that randomised patients had a higher intensity of abdominal pain, a higher consultation rate, and a longer history of irritable bowel syndrome.26

We allowed all patients with a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome according to their general practitioner to participate in the study in order to optimise the applicability of the results to primary care clinical practice. A sizeable proportion (61%) of our patients did not fulfil the Rome II criteria. Subgroup analysis showed a clinically relevant effect in both the complete study population and patients who met the Rome II criteria, although, as may be expected, the benefit was somewhat greater in the second group. The Rome criteria for irritable bowel syndrome have been developed mainly for research purposes and are infrequently used in primary care.5 6 7 8

Successful blinding of dietary interventions in research is difficult to achieve, but we took maximum precautions to guarantee that the treatments looked identical as regards packaging and content. Clinical staff involved were kept blinded to treatment allocation throughout the study. However, in retrospect approximately three quarters of patients correctly guessed which treatment they were given. We have no clear explanation for this. Partly, the appearance or the taste of the treatment may have been the reason, but patients may also have recognised the effect of soluble or insoluble fibre supplements from previous experience. For instance, a fibre supplement might produce a greater sense of bloating than rice flour.

Forty per cent of the patients in this study stopped participation before the final visit. The main reason was that they felt worse when taking the fibre supplement. Although this dropout rate is considerable, it is comparable to that in other trials of this nature.27 28 29 The motivation of patients to participate rapidly drops when an intervention is cumbersome or time consuming, especially when it does not lead to any immediate effect or is difficult to tolerate. Obviously, a high dropout rate is going to contribute negatively to the overall result of the study, especially when these patients are classified as treatment failures. Although this “worst case scenario” is the most appropriate way of analysing the effectiveness of treatment, it may underestimate the true effectiveness of fibre treatment.20

The dropout rate was highest among those patients randomised to bran, and this mainly occurred during the first month of treatment. This was mainly attributed to worsening of symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. This has also been reported in secondary care,30 31 and it is supported by the finding that the number of patients stopping treatment because of intolerance was twice as high in the bran group as in the psyllium or placebo group. Probably, those left in the trial taking bran were a small subset of patients who responded well to this supplement, as is also indicated by the comparable adverse event rates reported in the three groups.

Implications of findings

The results of this large scale trial in primary care support the addition of soluble fibre, such as psyllium, but not bran as an effective first treatment approach in the clinical management of patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

What is already known on this topic

Increasing dietary fibre (either insoluble or soluble) is almost universally advocated for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome

No trial has assessed its effects in the primary care setting, where the vast majority of these patients are managed

What this study adds

The addition of soluble fibre (psyllium) but not insoluble fibre (bran) was effective in the clinical management of patients with irritable bowel syndrome in primary care

The benefit of psyllium may be somewhat greater in patients who fulfil the Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome

Bran may worsen symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, especially at the beginning of treatment, and should be advised only with caution

We thank all participating patients and the general practitioners, assistants, and nurses in the participating practices. We thank B Slotboom for his valuable assistance in constructing the data file and P Zuithoff for statistical advice.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of the trial, interpretation of the results, and writing of the manuscript. CJB contributed to the recruitment of general practitioners and patients, data collection, management of the trial, and statistical analysis. NJdW recruited general practitioners and co-coordinated the trial. JWMM recruited general practitioners. PJW and JAK contributed to the statistical analysis. AWH co-coordinated the trial and contributed to the statistical analysis. All authors met regularly as a steering group. CJB is the guarantor.

Funding: The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development provided peer-reviewed funding for this study. The psyllium for this study was delivered by Pfizer BV, the Netherlands. The sponsors of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The medical ethics committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht approved the study protocol. All patients gave written informed consent.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3154

References

- 1.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones R. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care. BMJ 2008;337:a2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, Smyth C. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut 2000;46:78-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruigomez A, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Garcia Rodriguez LA. One-year follow-up of newly diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13:1097-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mearin F, Badia X, Balboa A, Baro E, Caldwell E, Cucala M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome prevalence varies enormously depending on the employed diagnostic criteria: comparison of Rome II versus previous criteria in a general population. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001;36:1155-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandvik PO, Aabakken L, Farup PG. Diagnosing irritable bowel syndrome: poor agreement between general practitioners and the Rome II criteria. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:448-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen HA, Borghouts JA, Muris JW, Metsemakers JF, Koes BW, Knottnerus JA. Health status and management of chronic non-specific abdominal complaints in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:375-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oberndorff-Klein Woolthuis AH, Brummer RJ, de Wit NJ, Muris JW, Stockbrugger RW. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: an overview. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 2004;241:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bijkerk CJ, de Wit NJ, Stalman WA, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW, Muris JW. Irritable bowel syndrome in primary care: the patients’ and doctors’ views on symptoms, etiology and management. Can J Gastroenterol 2003;17:363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller V, Lea R, Agrawal A, Whorwell PJ. Bran and irritable bowel syndrome: the primary care perspective. Dig Liver Dis 2006;38:737-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis CY, Whorwell PJ. Bran and irritable bowel syndrome: time for reappraisal. Lancet 1994;344:39-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bijkerk CJ, Muris JW, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW, de Wit NJ. Systematic review: the role of different types of fibre in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:245-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford AC, Tally NJ, Spiegel BMR, Foxx-Orenstein AC, Schiller L, Quigley EMM, et al. Effect of fibre, antispasmodics and peppermint oil in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;337:a2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longstreth GF, Hawkey CJ, Mayer EA, Jones RH, Naesdal J, Wilson IK, et al. Characteristics of patients with irritable bowel syndrome recruited from three sources: implications for clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:959-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Horst HE, van Dulmen AM, Schellevis FG, van Eijk JT, Fennis JF, Bleijenberg G. Do patients with irritable bowel syndrome in primary care really differ from outpatients with irritable bowel syndrome? Gut 1997;41:669-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Classification Committee of WONCA. ICHPPC-2 defined: international classification of health problems in primary care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- 17.Boukes FS, van der Horst HE, Assendelft WJ. [Summary of the Dutch College of General Practitioners’ “irritable bowel syndrome” standard.] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2002;146:799-802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Staveren WA, Hautvast JG, Katan MB, Van Montfort MA, Van Oosten-Van Der Goes HG. Dietary fibre consumption in an adult Dutch population. J Am Diet Assoc 1982;80:324-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bijkerk CJ, de Wit NJ, Muris JW, Jones RH, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW. Outcome measures in irritable bowel syndrome: comparison of psychometric and methodological characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irvine EJ, Whitehead WE, Chey WD, Matsueda K, Shaw M, Talley NJ, et al. Design of treatment trials for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1538-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangel AW, Hahn BA, Heath AT, Northcutt AR, Kong S, Dukes GE, et al. Adequate relief as an endpoint in clinical trials in irritable bowel syndrome. J Int Med Res 1998;26:76-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997;11:395-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO, DiCesare J, Puder KL. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development and validation of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:400-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ocke MC, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Goddijn HE, Jansen A, Pols MA, Van Staveren WA, et al. The Dutch EPIC food frequency questionnaire. I. Description of the questionnaire, and relative validity and reproducibility for food groups. Int J Epidemiol 1997;26:S37-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ocke MC, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Pols MA, Smit HA, Van Staveren WA, Kromhout D. The Dutch EPIC food frequency questionnaire. II. Relative validity and reproducibility for nutrients. Int J Epidemiol 1997;26:S49-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bijkerk CJ, Muris JWM, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW, de Wit NJ. Randomised patients in irritable bowel syndrome research had different disease characteristics compared to eligible unrecruited patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;11:1176-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parisi G, Bottona E, Carrara M, Cardin F, Faedo A, Goldin D, et al. Treatment effects of partially hydrolyzed guar gum on symptoms and quality of life of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a multicenter randomized open trial. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:1107-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rees G, Davies J, Thompson R, Parker M, Liepins P. Randomised-controlled trial of a fibre supplement on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. J R Soc Health 2005;125:30-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snook J, Shepherd HA. Bran supplementation in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1994;8:511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal A, Whorwell PJ. Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis and management. BMJ 2006;332:280-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalrymple J, Bullock I. Diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary care: summary of the NICE guidance. BMJ 2008;336:556-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]