Abstract

Autolysis plays an essential role in bacterial cell division and lysis with β-lactam antibiotics. Accordingly, the expression of autolysins is tightly regulated by several endogenous regulators, including ArlRS, a two component regulatory system that has been shown to negatively regulate autolysis in methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) strains. In this study, we found that inactivation of arlRS does not play a role in autolysis of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains, such as community-acquired (CA)-MRSA strains USA300 and MW2 or the hospital-acquired (HA)-MRSA strain COL. This contrasts with MSSA strains, including Newman, SH1000, RN6390, and 8325-4, where autolysis is affected by ArlRS. We further demonstrated that the striking difference in the roles of arlRS between MSSA and MRSA strains is not due to the methicillin resistance determinant mecA. Among known autolysins and their regulators, we found that arlRS represses lytN, while no effect was seen on atl, lytM, and lytH expression in both CA- and HA-MRSA strains. Transcriptional-fusion assays showed that the agr transcripts, RNAII and RNAIII, were significantly more downregulated in the arlRS mutant of MW2 than the MSSA strain Newman. Importantly, provision of agr RNAIII in trans to the MW2 arlRS mutant via a multicopy plasmid induced autolysis in this MRSA strain. Also, the autolytic phenotype in the arlRS mutant of MSSA strain Newman could be rescued by a mutation in either atl or lytM. Together, these data showed that ArlRS impacts autolysis differently in MSSA and MRSA strains.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus, classically described as a nosocomial pathogen, has now surfaced as a common cause of community-acquired infections, primarily due to the emergence of strain USA300 and, to a lesser extent, USA400 (5). Recent reports suggest that community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) infections can occur in the hospital environment (6, 27, 36, 43). The potential replacement of hospital-acquired (HA)- with CA-MRSA strains in nosocomial infections is of concern because CA-MRSA strains appear to be more virulent than HA-MRSA. In addition, treatment options have been hampered due to a reduction in the efficacy of antibiotics.

Autolysis, which plays an essential role in cell wall turnover, can be triggered by antibiotics or adverse physiological conditions (29, 45). S. aureus is known to carry several known or putative autolysin (or peptidoglycan hydrolase) genes, including the major autolysin genes atl, lytM, lytH, and lytN, none of which are essential for viability. The major autolysin Atl is a 138-kDa bifunctional protein that undergoes proteolytic processing to generate a 62-kDa N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase and a 51-kDa endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (26, 35). LytM is a 32-kDa glycyl-glycine endopeptidase that cleaves the pentaglycine linkage between peptidoglycan chains in a manner similar to that of lysostaphin (12, 34, 38). LytH (30 kDa), LytN (46 kDa), and LytA (50 kDa) are peptidoglycan hydrolases with N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase activity (17, 24, 44, 48).

For cell wall homeostasis, autolysin expression is generally tightly regulated. Negative regulators of autolysis include ArlRS, MgrA, LytSR, ClpP, SarA, and SarV, while agr and CidABC are positive regulators (15, 16, 23, 28, 30, 32, 39, 46). In this study, we focused on the two-component regulatory system ArlRS which was previously shown to be a repressor of autolysis in the methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) strain 8325-4 (15). In this paper, we decided to examine the role of ArlRS in clinically relevant MRSA strains. We found that the negative regulation of autolysis by ArlRS occurs in MSSA strains, including Newman, 6390, SH1000, and 8325-4, but not in any of the MRSA strains selected for this study, including HA-MRSA strain COL and CA-MRSA strains MW2 (USA400) and USA300. This difference in autolysis between MSSA and MRSA strains was not attributable to mecA but can be explained in part by a difference in agr expression between the two strain sets. Importantly, provision of agr in trans to the arlRS mutant of MW2 via a multicopy plasmid with an exogenous promoter induced autolysis in the mutant. These studies support the divergent roles of ArlRS in inducing autolysis in MRSA and MSSA strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The E. coli strain XL-1 blue was used in cloning experiments. The wild-type and mutant S. aureus strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani medium (Becton Dickinson) was used for culture of E. coli, while Trypticase soy broth (TSB) was used for growth of S. aureus. When appropriate, antibiotics (Sigma) were added to the media at the following concentrations: ampicillin at 100 μg/ml for E. coli and chloramphenicol at 10 μg/ml and erythromycin at 2.5 μg/ml for S. aureus. Chloramphenicol was routinely used to maintain selection for pEPSA5- and pSK236-based plasmids.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Comment | Source |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus strains | ||

| RN4220 | Heavily mutagenized MSSA strain; derivative of 8325-4; agr mutant acceptor of foreign DNA | 41 |

| MW2 (USA400) | CA-MRSA; wild-type strain isolated in 1998 in North Dakota | 3 |

| MW2 arlRS | ΔarlRS in-frame deletion mutant of MW2 | This study |

| MW2 mecA | ΔmecA in-frame deletion mutant of MW2 | This study |

| MW2 arlRS-mecA | ΔarlRS and ΔmecA in-frame double-deletion mutant of MW2 | This study |

| MW2 arlRS::arlRS | ΔarlRS complemented with arlRS with pMAD cycling | This study |

| MW2 arlRS with pEPSA5::arlRS | ΔarlRS complemented with arlRS on pEPSA5 | This study |

| USA300 | CA-MRSA; wild-type strain | This study |

| USA300 arlRS | ΔarlRS in-frame deletion mutant of USA300 | This study |

| COL | HA-MRSA, wild-type strain isolated from a human infection in the early 1960s | 9, 20, 49 |

| COL arlRS | ΔarlRS in-frame deletion mutant of COL | This study |

| Newman | MSSA; wild-type strain isolated from a human infection in 1952 | 11 |

| Newman arlRS | ΔarlRS in-frame deletion mutant of Newman | This study |

| Newman lytN | ΔlytN in-frame deletion mutant of Newman | This study |

| Newman lytM | ΔlytM in-frame deletion mutant of Newman | This study |

| Newman atl | Δatl in-frame deletion mutant of Newman | This study |

| Newman arlRS-lytN | ΔarlRS and ΔlytN in-frame double-deletion mutant of Newman | This study |

| Newman arlRS-lytM | ΔarlRS and ΔlytM in-frame double-deletion mutant of Newman | This study |

| Newman arlRS-atl | ΔarlRS and Δatl in-frame double-deletion mutant of Newman | This study |

| Newman::mecA | MSSA wild-type strain expressing mecA on pEPSA5; fully methicillin resistant | This study |

| Newman arlRS::mecA | ΔarlRS of Newman expressing mecA on pEPSA5; fully methicillin resistant | This study |

| SH1000 | MSSA; wild-type strain 8325-4 with rsbU restored | 21 |

| SH1000 arlRS | ΔarlRS in-frame deletion mutant of SH1000 | This study |

| RN6390 | MSSA; wild-type strain; agr+ laboratory strain related to 8325-4; maintains hemolytic pattern when propagated on sheep erythrocytes | 37 |

| RN6390 arlRS | ΔarlRS in-frame deletion mutant of 6390 | This study |

| 8325 | MSSA; wild-type strain; prophage-cured strain of NCTC8325 harboring an 11-bp deletion in rsbU that regulates sigB activity by activating RsbV | 33 |

| 8325 arlRS | ΔarlRS in-frame deletion mutant of strain 8325 | This study |

| E. coli XL-1 blue | General laboratory cloning strain | 40 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMAD | Allelic replacement vector to generate S. aureus mutant strains | 1 |

| pEPSA5 | Ectopic expression vector (pEPSA5) for genes in S. aureus | 13 |

| pMAD arlRS− | pMAD containing ∼0.8 kb up- and downstream fragments of arlRS for deletion (DNAs from MW2, USA300, COL, Newman, SH1000, 6390, or 8325) | This study |

| pMAD arlRS+ | pMAD containing the arlRS genes and ∼0.8 kb up- and downstream from MW2 or Newman for complementation | This study |

| pMAD− MW2 mecA− | pMAD containing ∼0.8 kb up- and downstream MW2 fragments of mecA for deletion | This study |

| pMAD Newman lytN− | pMAD containing ∼0.8 kb up- and downstream Newman fragments of lytN for deletion | This study |

| pMAD Newman lytM− | pMAD containing ∼0.8 kb up- and downstream Newman fragments of lytM for deletion | This study |

| pMAD Newman atl− | pMAD containing ∼0.8 kb up- and downstream Newman fragments of atl for deletion | This study |

| pEPSA5::arlRS | pEPSA5 containing 2-kb DNA fragment containing the arlRS coding regions, including their own RBSa from MW2 or Newman at the SalI/PstI sites | This study |

| pEPSA5::mecA | pEPSA5 containing 2-kb DNA fragment containing the mecA coding region, including its own RBS from MW2 at the BamHI/XbaI sites | This study |

RBS, ribosome binding site.

Susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined in triplicate by microdilution techniques, using an inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/ml according to the CLSI guideline (10). For each mutant, three independent clones were tested, with the MIC data reported as median values from at least three independent experiments for each antibiotic. Strains containing pEPSA5-based plasmids were tested with and without xylose induction, but chloramphenicol was not added in these assays to avoid interference with β-lactam resistance evaluation.

DNA techniques.

Standard molecular-cloning techniques were used, as described previously (40). Restriction enzymes and ligases were from New England BioLabs. I-Proof DNA polymerase (Bio-Rad) was used to generate all DNA fragments for gene deletions, promoter fusions, and ectopic expression in pEPSA5. The fidelity of all DNA sequences generated by PCR was verified by fluorescently labeled dideoxynucleotide sequencing (BigDye terminators; PE Applied Biosystems).

Construction of S. aureus mutants.

All mutants were generated with in-frame deletion of target genes by allelic replacement, using the temperature-sensitive plasmid pMAD as described previously (31). This method allows the disruption of genes without the insertion of an antibiotic resistance marker. Briefly, ∼0.8-kb PCR products upstream and downstream of targeted sequences were cloned into pMAD, amplified in E. coli, and transformed into S. aureus RN4220 and then into the target strain, followed by the process of allelic replacement as delineated previously (1). All chromosomal deletions were verified by PCR and DNA sequencing. The resulting deletion strains were devoid of both arlR and arlS open reading frames (ORFs), with at least three clones each used for characterization. The same pMAD system was also utilized to reinsert the native arlRS ORFs into the MW2 ΔarlRS for complementation. Complementation was also attempted by cloning arlRS in the xylose-inducible vector pEPSA5. The sequences of DNA primers used in this study are available on request.

Isolation of RNA and Northern blot hybridization.

Overnight cultures of S. aureus were diluted 1:100 in 40 ml of TSB and grown in 200-ml flasks with shaking to reach exponential phase (A650 = 0.7 in Spectronic 20), using 18-mm borosilicate glass tubes. At an optical density (OD) of 0.7, total RNA was extracted from 10 ml of culture by using a TRIzol-glass bead method, as described previously (30). After growth for an additional 60 min, RNAs were extracted from all samples. Ten micrograms each of total RNA was analyzed by Northern blotting with gel-purified DNA probes (∼350 bp each) radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP using the random-primed DNA-labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) and hybridized under aqueous-phase conditions at 65°C. The blots were subsequently washed, and the bands were visualized by autoradiography. Three independent clones were utilized to extract RNA from each strain and tested in Northern blot analysis.

Transcriptional-fusion studies of the P3 agr promoter linked to the green fluorescent protein (GFPuvr) reporter gene.

To confirm the effect of the arlRS deletions on agr transcription, we cloned the agr P3 promoter in pALC1484, a derivative of pSK236 containing the promoterless gfpuvr to generate transcriptional fusions, as confirmed by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing. Recombinant promoter fusion plasmids were introduced into S. aureus RN4220, purified, and electroporated into wild-type MW2, Newman, and their isogenic arlRS mutants. For analysis, aliquots (200 μl) from overnight cultures of three independent clones were transferred to microtiter wells to assay for cell density (OD at 650 nm [OD650]) and fluorescence in an FL600 fluorescence reader (BioTek Instruments). Promoter activation was plotted as the mean fluorescence/OD650 ratio, using the average values from triplicate readings from three clones per strain.

Ectopic gene expression in S. aureus.

Besides pMAD-mediated complementation of the mutant strains, we also utilized the plasmid pEPSA5, which can be induced for expression with xylose (1%) (11). For pEPSA5-mediated expression, PCR-amplified gene fragments were ligated into pEPSA5 and transformed first into E. coli XL-1 blue and then into RN4220. Plasmids from positive clones of S. aureus RN4220 were then introduced into MW2, Newman, and their isogenic arlRS mutants as described above. For reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, extracted RNA was resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) water, treated with Turbo DNase I (Ambion), and then reverse transcribed with 1 μg of total RNA, using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). Regular PCR was then performed on cDNAs using oligonucleotides specific for each gene. For agr overexpression, we utilized pRN6735 (47), which is a derivative of pC194 containing the pI258 bla promoter and two-thirds of the structural gene (blaZ), followed by the 1,566-bp MboI fragment containing the RNAIII determinant lacking its own promoter. The cloned bla promoter is repressed by pI524 in the tested strain, which supplies the bla repressor in trans. Under these conditions, the bla promoter is inducible by β-lactam compounds, such as oxacillin.

X-100-induced autolysis assays in growing cultures.

The autolysis assay was performed as described previously (23). Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 to an OD650 of 0.1 in TSB and grown at 37°C with shaking in the presence of Triton X-100, with the OD600 recorded hourly for 7 to 8 h. Each data point represents the mean and standard deviation from three independent experiments.

Zymogram analysis.

Zymogram analysis was conducted to detect alterations in autolysin activity as described previously, with minor alterations (23). Cell fractions containing autolytic enzymes from MW2, Newman, and their isogenic ΔarlRS mutants were extracted from the cell pellet of a 10-ml bacterial culture grown to an OD650 of 0.7 using 100 μl of 4% SDS. Equivalent amounts of extracted proteins were separated on the SDS-PAGE gel containing heat-killed RN4220 or Micrococcus lysodeikticus bacterial cells at 10 mg/ml (wet weight). The resolved proteins were allowed to renature overnight in water and were incubated with 0.5% methylene blue to visualize clear bands representing an area of cell lysis with RN4220 or M. lysodeikticus. The assay was repeated three times, and a representative experiment is shown.

RESULTS

Initial characterization of arlRS mutants in autolysis.

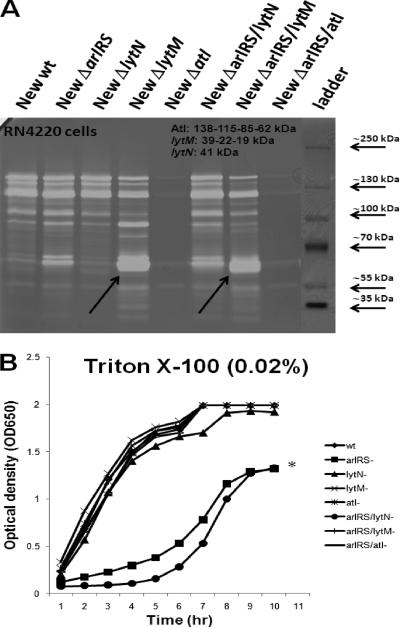

To assess the contribution of ArlRS to autolysis, we generated in-frame deletion mutants of both the histidine kinase and the response regulator in HA-MRSA strain COL, CA-MRSA strains MW2 and USA300, and MSSA strains Newman, SH1000, 8325-4, and RN6390 (Fig. 1C). We found that MSSA strain Newman, MRSA strain MW2, and their corresponding arlRS mutants grew comparably in TSB medium (Fig. 1A), similar to the growth of arlRS mutants and their respective parent strains in other MSSA and MRSA strains under study (data not shown). In the presence of Triton X-100, however, growth of all arlRS mutants in the MSSA background (8325-4, RN6390, Newman, and SH1000) was severely affected, while all arlRS mutants of MRSA strains (COL, MW2, and USA300) remained unaffected (Fig. 1B and data not shown). Given the above findings, we elected to focus most of our subsequent studies on MW2 and Newman, representing MRSA and MSSA strains, respectively.

Fig 1.

Increased autolysis of the arlRS mutant of strain Newman in TSB supplemented with 0.02% Triton X-100. (A and B) Growth curves of MW2, Newman, and their isogenic arlRS mutants with and without 0.02% Triton X-100. Overnight cultures were diluted to an OD650 of 0.1 in TSB, supplemented with 0.02% Triton X-100, and grown at 37°C with shaking. The asterisk indicates statistical significance of the growth of the arlRS mutant of Newman versus the parent strain at all time points by a paired Student t test (P < 0.001). WT, wild type. (C) Map of the arlRS TCRS locus. Shown are the open reading frame designations of the MW2 and Newman genomes, secondary gene names, proposed functions, translated protein sizes (amino acids [aa]), and the region deleted in the present study. (D) Deletion of arlRS does not significantly affect murein hydrolase activity in Newman (New) and MW2. Shown are zymogram analyses of cell extracts from S. aureus MW2, Newman, and their isogenic arlRS mutants. Equivalent amounts of cell extracts were separated on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing heat-killed S. aureus RN4220 cells (left) or Micrococcus lysodeikticus (right). The resolved gels were washed with water, incubated with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2, and CaCl2) for 18 to 24 h, and stained with 0.5% methylene blue. Areas of murein hydrolase activity are indicated by clear zones (the same results were obtained with heat-killed cells of Newman and MW2 arlRS mutants).

To exclude chromosomal rearrangement or an ectopic point mutation as the cause of the increased autolysis, the pMAD plasmid was also used to introduce the native arlRS genes into the ΔarlRS mutants of Newman and MW2. These chromosomally complemented strains regained wild-type levels of growth in the presence of Triton X-100 (Fig. 2A). Complementation was also obtained when arlRS were cloned into the xylose-inducible plasmid pEPSA5 (Fig. 2A), but not when arlR or arlS was singly expressed, possibly due to the high copy number of the sensor or the kinase gene provided by the plasmid or the fact that ArlR requires ArlS to function properly. We also examined the effects of arlRS mutations on genes upstream and downstream of arlRS in both MW2 and Newman arlRS mutants by Northern blotting and did not discern any significant polar effects as a result of the arlRS mutations (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Effects of complementation on autolysis of arlRS mutants of Newman and MW2. (A) Complementation of arlRS on the chromosome or in trans with pEPSA5::arlRS restored wild-type levels of growth in the presence of Triton X-100. Shown are growth curves of Newman, its isogenic arlRS mutant, and complemented strains with and without 0.02% Triton X-100. The asterisk indicates statistical significance of the growth of the arlRS mutant versus the parent strain Newman at all time points by a paired Student t test (P < 0.001). (B) Effect of mecA on autolysis of arlRS mutants of Newman and MW2. Deletion of mecA in the arlRS mutant of MW2 did not affect growth under autolysis-inducing conditions, while cross-complementation of the arlRS mutant of Newman had no effect on restoration of the defect in Triton X-100-induced autolysis. Shown are growth curves of the Newman wild type and the arlRS mutant carrying pEPSA5::mecA, MW2 mecA, and mecA-arlRS mutants in TSB-0.02% Triton X-100. The asterisk indicates statistical significance of the growth of the arlRS mutant versus its isogenic parent strain Newman at all time points by a paired Student t test (P < 0.001).

Given that autolysis might affect methicillin resistance, we also assayed the sensitivities of the arlRS mutants to oxacillin and nafcillin in both strains MW2 and Newman. Deletion of arlRS in both MW2 and Newman did not lead to a significant reduction in the MIC for oxacillin, nafcillin, or cefoxitin, which were the β-lactams selected for this study.

Effect of arlRS on zymographic profiling of autolysins in arlRS mutants.

Penicillins and β-lactams in general may enhance autolysis by triggering murein hydrolase activity on dividing cells (19). Although the arlRS system has previously been shown to be involved in autolysis by negatively regulating murein hydrolase expression in an MSSA strain, such as 8325-4 (15), its contribution to autolysis by zymogram analysis in clinically relevant MRSA strains has not been assessed. Accordingly, we performed zymogram analysis in isogenic arlRS strains of MW2 and compared them to those of the Newman background. As shown in Fig. 1D, there was no discernible change in the lytic profiles of various arlRS mutants compared with the parental controls, regardless of whether Micrococcus or S. aureus RN4220 was used as a substrate. We also deployed the Newman ΔarlRS strain as a cellular substrate in the gel to ascertain if increased autolysis in the arlRS mutant of Newman was due to a general increase in sensitivity to autolytic enzymes. However, these zymogram assays also showed no difference in the lytic band profiles between isogenic arlRS strains (data not shown).

Effect of mecA on Triton X-100-induced autolysis in arlRS mutants.

On the basis of similar autolytic defects between arlRS mutants of SigB-deficient RN6390 (also 8325-4) and strain SH1000 with SigB restored, we have excluded the role of sigma B as the primary cause of enhanced autolysis mediated by arlRS (data not shown). Similarly, a difference in saeRS expression, which was found to be constitutive in Newman but not in 6390, SH1000, and 8325-4 (18), likely fails to explain the differences in autolysis observed between MSSA and MRSA strains. We also tested the role of mecA by deleting the mecA gene in the arlRS mutant of MW2, as well as expressed mecA on the xylose-inducible plasmid pEPSA5 in the parental strain Newman and its isogenic arlRS mutant. In the mecA mutant of MW2, we deleted only the region encoding PBP2A in the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (SCCmec). These data (Fig. 2B) showed that deletion of mecA in MRSA strain MW2 did not alter growth in Triton X-100, while addition of mecA to the arlRS mutant of MSSA strain Newman, which, as expected, increased its resistance to oxacillin (the MIC increased from <0.5 to 64 μg/ml), also did not restore the autolysis defect in Triton X-100. Likewise, a combined mecA and arlRS deletion in MW2 did not affect growth in medium supplemented with Triton X-100. We also evaluated the expression of pbp2 and pbp4 and did not find any significant differences in the expression of these two genes between isogenic arlRS strains of Newman and MW2.

Effect of arlRS on expression of genes that regulate autolysis and murein hydrolase activity.

To assess whether the Triton X-100-induced autolysis of the arlRS mutant in Newman, but not in MW2, was due to different impacts on autolysin gene expression, Northern blots were conducted with DNA probes specific for the genes encoding major autolysins (atl, lytM, lytN, lytH, lytA, and sle1), the two-component regulatory system (TCRS) (lytSR), and the downstream effector lrgA, which encodes a putative antiholin that interferes with the transport of murein hydrolase across the cell membrane into the cell wall (7, 8). We did not observe any differences in the transcription of genes encoding autolysins (atl, lytM, lytH, lytA, and sle1) between parent and the isogenic arlRS mutants. However, lytN was significantly upregulated in the arlRS mutants of both MW2 and Newman (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, the transcription of lytRS, which is a repressor of autolytic activity, and its downstream effector lrgAB was reduced in the arlRS mutants of both MW2 and Newman (Fig. 3A). Notably, we were able to restore wild-type levels of transcription of these genes in complemented arlRS strains of both Newman and MW2 (data not shown). Given that these genes are affected in similar manners in both MSSA Newman and MRSA MW2 backgrounds, it is unlikely that differences in transcription of the genes (lytRS and lrgA) in isogenic strains of Newman and MW2 could explain the enhanced autolysis of MSSA strain Newman in Triton X-100 but not MRSA strain MW2. To partially confirm this, we deleted lrgAB in arlRS mutants of both Newman and MW2 and found no difference in growth under autolysis-inducing conditions (data not shown). Cross-complementation of the arlRS mutant of Newman in trans using a pEPSA5-based construct driving lrgAB expression also did not alleviate the Triton X-100-induced autolysis (data not shown).

Fig 3.

Effects of the arlRS mutation on the expression of autolysin genes and known lytic regulators. Shown is Northern blot analysis of lytN, lrgAB, and lytRS (A) and of mgrA, RNAII, and RNAIII (B) expression. The blots were hybridized with a DNA probe specific for each gene radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP. Below are shown the ethidium bromide-stained rRNAs, indicating equivalent amounts of RNA in each sample. The RNAs for each strain were extracted at OD650s of 0.7, 1.1, and 1.7, corresponding to exponential, late-exponential, and early-stationary phases, respectively. The experiment was repeated at least three times with similar results. A representative experiment is shown.

Effect of arlRS deletion on expression of mgrA and agr.

In our previous studies, we described mgrA as a positive regulator of agr and a negative regulator of autolysis by virtue of reduced agr and lrgAB expression in the mgrA mutant (22, 23). To ascertain whether the autolysis defect in MSSA strains was due to a different impact of arlRS deletion on either mgrA or agr, Northern blots were conducted with DNA probes specific for mgrA, RNAII, and RNAIII (Fig. 3B). Transcription of mgrA, which constitutes two overlapping transcripts from two distinct promoters, was greatly reduced in both MW2 and Newman backgrounds, although the reduction is more prominent in the Newman background. The most significant difference, however, involved transcription of both agr RNAII and RNAIII. While a modest reduction of both transcripts was observed with the arlRS mutant of Newman, both transcripts are markedly reduced in the arlRS mutant of MW2 (Fig. 3B). To further confirm the effect of arlRS on agr expression, we conducted transcriptional fusion of the agr P3 promoter linked to the GFPuvr reporter gene. Transcriptional-fusion studies revealed that agr expression is significantly downregulated in the arlRS mutant of MW2, while the effect was more modest in the Newman background (Fig. 4). Complementation of the arlRS mutants in MW2 and Newman restored expression of RNAIII, as confirmed by GFP-promoter fusion (Fig. 4) and Northern analysis (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Regulation of ArlRS on RNAIII. Shown is the expression of GFPuvr driven by the agr P3 promoter in overnight cultures. Promoter activity was plotted as mean fluorescence/OD650 from 3 clones in triplicate. The experiments were repeated three times, with one set shown. The asterisk indicates statistical significance of the indicated strain compared to MW2 by a paired Student t test (P < 0.001). comp, complementation.

Effect of RNAIII overexpression on autolysis in MW2.

Northern blots and promoter fusions indicated that expression of agr RNAIII was significantly downregulated in the arlRS mutant of MW2 (Fig. 3B and 4). As agr has been described as a positive regulator of autolysis (14), we wanted to ascertain the effect of RNAIII overexpression in the arlRS mutant of MW2. For this experiment, pRN6735, which overexpressed RNAIII under a bla-inducible promoter in the presence of oxacillin (Fig. 5), was introduced into MW2 and its isogenic arlRS mutant. As shown in Fig. 5, overexpression of RNAIII under oxacillin induction was able to render the arlRS mutant of MW2 prone to autolysis in the presence of 0.02% Triton X-100, indicating that the downregulation of agr in the arlRS mutant of MW2 (Fig. 3B and 4) is likely a contributing factor to its resistance in Triton X-100-mediated autolysis compared to MSSA strain Newman. In contrast, overexpression of RNAIII in the parental strain MW2 did not have any major effect on autolysis, even under oxacillin induction. This finding indicated that, in addition to agr, another factor(s) regulated by arlRS may have contributed to the propensity for autolysis in arlRS mutants.

Fig 5.

Overexpression of RNAIII affects growth of the arlRS mutant of MW2 under autolysis-inducing conditions. (Left) Growth curves of MW2 and its isogenic arlRS mutant carrying pRN6735 with 0.02% Triton X-100. (Right) Expression of RNAIII of the arlRS mutant of MW2 with and without induction with a sub-MIC concentration of oxacillin. The asterisk indicates statistical significance at OD650 for growth of the arlRS mutant of MW2 overexpressing agr at all time points by a paired Student t test (P < 0.001).

Effect of arlRS deletion in combination with autolysins on growth and murein hydrolase activity.

To assess if the increased autolysis of the arlRS mutant of Newman was dependent on overexpression of LytN (Fig. 6A) or on a mechanism involving other known autolysins, in-frame deletion mutants were made for lytN, atl, or lytM singularly and in combination with the arlRS mutation. All these new isogenic mutant strains grew similarly in TSB in the absence of Triton X-100 (data not shown). In the presence of 0.02% Triton X-100, however, mutation of either atl or lytM in combination with arlRS restored the autolytic defect while lytN did not (Fig. 6B). To determine the effects of these mutations on cell wall murein hydrolase activity, zymogram analysis was performed with wild-type Newman and its isogenic mutant strains. As shown in Fig. 6A, an atl deletion with or without arlRS mutation virtually abolishes all murein hydrolase activity, in line with previous studies (14, 25). A lytM deletion, with or without ArlRS, leads to a noticeable increase in the ∼60-kDa lytic band, which may correspond to the 62-kDa amidase domain of Atl. Whether LytM might play a role in processing the Atl amidase domain or whether the effect of ArlRS on LytM or Atl may be posttranscriptional remains to be determined.

Fig 6.

Deletion of atl or lytM affects murein hydrolase activity and restores growth in a Newman arlRS mutant strain under autolysis-inducing conditions. (A) Zymogram analysis of cell extracts from S. aureus Newman and its isogenic arlRS, lytN, lytM, atl, and double mutants. Equivalent amounts of cell extracts were separated on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing heat-killed S. aureus RN4220 cells. After electrophoresis, the gels were washed with water and then buffer and finally stained with 0.5% methylene blue as described in Materials and Methods. Areas of murein hydrolase activity are indicated by clear zones. The arrows indicate bands of increased activity in lytM and arlRS-lytM mutants. (B) Growth curves of Newman and its isogenic arlRS, lytN, lytM, atl, and double mutants with 0.02% Triton X-100. Overnight cultures were diluted to an OD650 of 0.1 in TSB, supplemented with 0.02% Triton X-100, and grown at 37°C with shaking. The asterisk indicates statistical significance of growth of arlRS and arlRS-lytN mutants versus the parent strain Newman at all time points by a paired Student t test (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

TCRSs are widely used signal transduction devices that engage in a multitude of gene regulatory events in response to changing environmental conditions (4). In previous studies, it has been shown that a mutation in the TCRS arlRS resulted in an increase in autolysis in a derivative of strain 8325-4 (15). However, we show here that a deletion in TCRS arlRS leads to enhanced autolysis in Triton X-100 only in methicillin-sensitive strains (15, 28), including Newman, SH1000, 6390, and 8325-4 (Fig. 1), but not in MRSA strains (CA-MRSA strains MW2 and USA300 and HA-MRSA strain COL) (Fig. 1). This result is surprising, considering that phylogenetically, staphylococcal strains Newman and NCTC8325 are related to MRSA strains COL and USA300 (2). We have excluded sigma B and saeRS as plausible causes to account for the difference in autolysis between arlRS mutants of MSSA and MRSA strains because both sigma B-positive and -negative strains (RN6390, 8325, Newman, and SH1000), and also strains with growth-phase-dependent expression (6390, SH100, and 8325), as well as constitutive expression of saeRS (Newman) (18), all exhibited defects in autolysis in Triton X-100 in the presence of an arlRS mutation. Despite these autolytic defects, murein hydrolase activities among MW2, Newman, and their arlRS isogenic mutant strains were similar. This result, combined with our finding that Triton X-100 induced autolysis in actively growing cells, may be attributable to a lack of sensitivity of our zymogram analysis assay.

We also could not attribute a lack of an autolysis defect in MW2 and its isogenic arlRS mutant to mecA, because the increase in autolysis was not detected in the arlRS-mecA double mutant. Furthermore, overexpression of mecA using the inducible system pEPSA5::mecA also did not rescue growth under Triton X-100 in the ΔarlRS mutant of Newman, even though mecA rendered Newman and its arlRS isogenic mutant fully oxacillin resistant (Fig. 2).

S. aureus carries several known or putative peptidoglycan hydrolases, including the major autolysin genes atl, lytM, lytH, lytN, lytA, and sle1. However, we did not find any differences in atl, lytM, lytH, lytA, and sle1 transcription between the arlRS mutants and the isogenic parents. The observation that lytN transcription was upregulated in similar manners between the arlRS mutants and respective parents suggests that lytN is unlikely to explain the divergent propensities of the arlRS mutants for autolysis between MW2 and Newman. In addition, a lytN mutant of Newman also did not exhibit a significant increase in murein hydrolase activity compared with the parent (Fig. 6), again emphasizing a marginal role for lytN in the different autolytic phenotypes between the two backgrounds.

The increased rate of autolysis in arlRS mutants of MSSA strains has been linked to downregulation of lytRS and the ensuing reduced expression of lrgAB (28), which interfere with the transport of murein hydrolase from the cytosol to the cell wall. As with lytN, both lytRS and lrgAB are downregulated in the arlRS mutants of MW2 and Newman (Fig. 3). In addition, complementation of lrgAB in trans did not positively affect the growth of the arlRS mutant of strain Newman under autolytic conditions (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that lrgAB did not play a major role in autolysis in MRSA strains, in contrast to what has been found in strain 8325-4 (13).

SarA, MgrA, and AgrA have also been shown to affect autolysis, with the first two regulators being repressors of autolysis and the last being an activator (16, 23, 46). We found that sarA transcription was not affected in the arlRS mutant. In a previous study, we showed that arlRS transcripts were downmodulated in an mgrA mutant (23). Here, we have shown that regulation is reciprocal in that mgrA transcription is also downmodulated in arlRS mutants of MW2 and Newman, although the difference is more prominent in the Newman background (Fig. 3). A significant difference was also seen in the agr RNAII and RNAIII transcript levels in the ΔarlRS mutant of MW2 compared to Newman ΔarlRS, as assessed by Northern blot analysis and GFP-promoter fusions. Fujimoto and Bayles have also shown that an agr mutant has a lower rate of autolysis than the wild-type RN6390 strain (16), suggesting that agr is likely a positive regulator of murein hydrolase activity. To confirm that this is also the case with MW2, we overexpressed agr RNAIII with a plasmid containing a β-lactamase-inducible promoter driving RNAIII. Our results showed that overexpression of RNAIII under oxacillin induction could render the arlRS mutant of MW2 susceptible to hydrolysis in the presence of Triton X-100 (Fig. 5). This effect is not due to oxacillin alone, since MW2, upon exposure to a sub-MIC level of oxacillin, did not display a dramatic increase in autolysis compared to the control (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, it is clear that the dosage of RNAIII plays a crucial role in autolysis, because the augmentation in autolytic activity in the arlRS mutant of MW2 was very mild in the absence of oxacillin induction.

Besides MW2, we also ascertained if the hyperautolytic phenotype in the arlRS mutant of Newman could be rescued by inactivating the major autolysin genes atl, lytM, lytN, and lytH. Remarkably, inactivation of Atl or LytM in the arlRS mutant of Newman was able to restore the growth pattern of the mutant to comparable to that of the parental strain in 0.02% Triton X-100, whereas a lytN or lytH mutation in the arlRS mutant had no effect (Fig. 6B). Notably, an atl deletion virtually abolished murein hydrolase activity in both wild-type Newman and its isogenic arlRS mutant, while a mutation in lytM led to a significant increase in an ∼62-kDa band that may correspond to the Atl-derived amidase domain in both Newman and its isogenic arlRS mutant.

Given that many of the MSSA strains (e.g., 8325-4 and SH1000) under laboratory investigation do not represent clinically relevant isolates, our study here on the mechanisms of autolysis in a CA-MRSA strain such as MW2 likely provides highly relevant information on autolysis under antibiotic-inducing conditions. In particular, our data here reveal that deletion of arlRS in MSSA strains, but not in MRSA strains, leads to a very significant increase in Triton X-100-induced autolysis that is not attributable to alterations in the expression of sigma B, saeRS, or mecA. We also found that significant downregulation of RNAIII in MW2, which is a positive regulator of autolysis, may be part of the mechanism by which a mutation of arlRS in clinically relevant MRSA strains may be resistant to autolysis in the presence of a small amount of nonionic detergent or cell wall-active antibiotics. Nevertheless, it is clear that the effect of RNAIII on autolysis is dosage dependent. In this context, it will be crucial to determine the expression of RNAIII in clinically relevant MRSA strains under antibiotic stress, which can promote autolysis. The fact that overexpression of RNAIII in the wild-type MW2 did not induce autolysis implies that there is an additional factor(s) controlled by ArlRS that likely contributes to autolysis. In a recent study, Schlag et al. described the role of wall teichoic acid in targeting Atl to the staphylococcal cross-wall (42). In the absence of wall teichoic acid, Atl is evenly distributed on the cell surface, thus increasing susceptibility to autolysis. Whether arlRS affects the synthesis or distribution of wall teichoic acid in S. aureus was not defined in our studies. Nevertheless, understanding the additional genetic determinants that account for this increased autolysis in MRSA strains could potentially lead to the development of novel strategies against MRSA infections.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 December 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Arnaud M, Chastanet A, Debarbouille M. 2004. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6887–6891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baba T, Bae T, Schneewind O, Takeuchi F, Hiramatsu K. 2008. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes: polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J. Bacteriol. 190:300–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baba T, et al. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beier D, Gross R. 2006. Regulation of bacterial virulence by two-component systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boucher HW, Corey GR. 2008. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46(Suppl. 5):S344–S349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bratu S, et al. 2005. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospital nursery and maternity units. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:808–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brunskill EW, Bayles KW. 1996. Identification and molecular characterization of a putative regulatory locus that affects autolysis in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 178:611–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brunskill EW, Bayles KW. 1996. Identification of LytSR-regulated genes from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 178:5810–5812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chambers HF, Hartman BJ, Tomasz A. 1985. Increased amounts of a novel penicillin-binding protein in a strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus exposed to nafcillin. J. Clin. Invest. 76:325–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 7th ed Document M7-A7. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duthie ES, Lorenz LL. 1952. Staphylococcal coagulase; mode of action and antigenicity. J. Gen. Microbiol. 6:95–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Firczuk M, Mucha A, Bochtler M. 2005. Crystal structures of active LytM. J. Mol. Biol. 354:578–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Forsyth RA, et al. 2002. A genome-wide strategy for the identification of essential genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1387–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Foster SJ. 1995. Molecular characterization and functional analysis of the major autolysin of Staphylococcus aureus 8325/4. J. Bacteriol. 177:5723–5725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fournier B, Hooper DC. 2000. A new two-component regulatory system involved in adhesion, autolysis, and extracellular proteolytic activity of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 182:3955–3964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fujimoto DF, Bayles KW. 1998. Opposing roles of the Staphylococcus aureus virulence regulators, Agr and Sar, in Triton X-100- and penicillin-induced autolysis. J. Bacteriol. 180:3724–3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fujimura T, Murakami K. 1997. Increase of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus caused by deletion of a gene whose product is homologous to lytic enzymes. J. Bacteriol. 179:6294–6301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Geiger T, Goerke C, Mainiero M, Kraus D, Wolz C. 2008. The virulence regulator Sae of Staphylococcus aureus: promoter activities and response to phagocytosis-related signals. J. Bacteriol. 190:3419–3428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giesbrecht P, Kersten T, Maidhof H, Wecke J. 1998. Staphylococcal cell wall: morphogenesis and fatal variations in the presence of penicillin. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1371–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gill SR, et al. 2005. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J. Bacteriol. 187:2426–2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horsburgh MJ, et al. 2002. sigmaB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. J. Bacteriol. 184:5457–5467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ingavale S, van Wamel W, Luong TT, Lee CY, Cheung AL. 2005. Rat/MgrA, a regulator of autolysis, is a regulator of virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 73:1423–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ingavale SS, Van Wamel W, Cheung AL. 2003. Characterization of RAT, an autolysis regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1451–1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jayaswal RK, Lee YI, Wilkinson BJ. 1990. Cloning and expression of a Staphylococcus aureus gene encoding a peptidoglycan hydrolase activity. J. Bacteriol. 172:5783–5788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaneda S. 1997. Isolation and characterization of autolysin-defective mutants of Staphylococcus aureus that form cell packets. Curr. Microbiol. 34:354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Komatsuzawa H, et al. 1997. Subcellular localization of the major autolysin, ATL and its processed proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Immunol. 41:469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kourbatova EV, et al. 2005. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA 300 clone as a cause of health care-associated infections among patients with prosthetic joint infections. Am. J. Infect. Control 33:385–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liang X, et al. 2005. Global regulation of gene expression by ArlRS, a two-component signal transduction regulatory system of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187:5486–5492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lopez R, Ronda-Lain C, Tapia A, Waks SB, Tomasz A. 1976. Suppression of the lytic and bactericidal effects of cell wall inhibitory antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 10:697–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manna AC, Ingavale SS, Maloney M, van Wamel W, Cheung AL. 2004. Identification of sarV (SA2062), a new transcriptional regulator, is repressed by SarA and MgrA (SA0641) and involved in the regulation of autolysis in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 186:5267–5280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Memmi G, Filipe SR, Pinho MG, Fu Z, Cheung A. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus PBP4 is essential for beta-lactam resistance in community-acquired methicillin resistant strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3955–3966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Michel A, et al. 2006. Global regulatory impact of ClpP protease of Staphylococcus aureus on regulons involved in virulence, oxidative stress response, autolysis, and DNA repair. J. Bacteriol. 188:5783–5796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Novick RP. 1990. The Staphylococcus as a molecular genetic system, p 1–40 In Novick RP. (ed), Molecular biology of the Staphylococcus. VCH Publishers, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 34. Odintsov SG, Sabala I, Marcyjaniak M, Bochtler M. 2004. Latent LytM at 1.3A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 335:775–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oshida T, et al. 1995. A Staphylococcus aureus autolysin that has an N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase domain and an endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase domain: cloning, sequence analysis, and characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:285–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Popovich KJ, Weinstein RA, Hota B. 2008. Are community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains replacing traditional nosocomial MRSA strains? Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:787–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Projan SJ, Novick RP. 1997. The molecular basis of pathogenicity, p 55–81 In Crossley KB, Archer GL. (ed), The staphylococci in human disease. Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ramadurai L, Jayaswal RK. 1997. Molecular cloning, sequencing, and expression of lytM, a unique autolytic gene of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 179:3625–3631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rice KC, et al. 2003. The Staphylococcus aureus cidAB operon: evaluation of its role in regulation of murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 185:2635–2643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schenk S, Laddaga RA. 1992. Improved method for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 73:133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schlag M, et al. 2010. Role of staphylococcal wall teichoic acid in targeting the major autolysin Atl. Mol. Microbiol. 75:864–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seybold U, et al. 2006. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genotype as a major cause of health care-associated blood stream infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sugai M, Fujiwara T, Komatsuzawa H, Suginaka H. 1998. Identification and molecular characterization of a gene homologous to epr (endopeptidase resistance gene) in Staphylococcus aureus. Gene 224:67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tomasz A, Waks S. 1975. Mechanism of action of penicillin: triggering of the pneumococcal autolytic enzyme by inhibitors of cell wall synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 72:4162–4166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Trotonda MP, Xiong YQ, Memmi G, Bayer AS, Cheung AL. 2009. Role of mgrA and sarA in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus autolysis and resistance to cell wall-active antibiotics. J. Infect. Dis. 199:209–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vandenesch F, Kornblum J, Novick RP. 1991. A temporal signal, independent of agr, is required for hla but not spa transcription in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 173:6313–6320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang X, Mani N, Pattee PA, Wilkinson BJ, Jayaswal RK. 1992. Analysis of a peptidoglycan hydrolase gene from Staphylococcus aureus NCTC 8325. J. Bacteriol. 174:6303–6306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yarwood JM, et al. 2002. Characterization and expression analysis of Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island 3. Implications for the evolution of staphylococcal pathogenicity islands. J. Biol. Chem. 277:13138–13147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]