Abstract

FlgJ plays a very important role in flagellar assembly. In the enteric bacteria, flgJ null mutants fail to produce the flagellar rods, hooks, and filaments but still assemble the integral membrane-supramembrane (MS) rings. These mutants are nonmotile. The FlgJ proteins consist of two functional domains. The N-terminal rod-capping domain acts as a scaffold for rod assembly, and the C-terminal domain acts as a peptidoglycan (PG) hydrolase (PGase), which allows the elongating flagellar rod to penetrate through the PG layer. However, the FlgJ homologs in several bacterial phyla (including spirochetes) often lack the PGase domain. The function of these single-domain FlgJ proteins remains elusive. Herein, a single-domain FlgJ homolog (FlgJBb) was studied in the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Cryo-electron tomography analysis revealed that the flgJBb mutant still assembled intact flagellar basal bodies but had fewer and disoriented flagellar hooks and filaments. Consistently, Western blots showed that the levels of flagellar hook (FlgE) and filament (FlaB) proteins were substantially decreased in the flgJBb mutant. Further studies disclosed that the decreases of FlgE and FlaB in the mutant occurred at the posttranscriptional level. Microscopic observation and swarm plate assay showed that the motility of the flgJBb mutant was partially deficient. The altered phenotypes were completely restored when the mutant was complemented. Collectively, these results indicate that FlgJBb is involved in the assembly of the flagellar hook and filament but not the flagellar rod in B. burgdorferi. The observed phenotype is different from that of flgJ mutants in the enteric bacteria.

INTRODUCTION

The bacterial flagellum is a sophisticated macromolecular complex. Its structure and assembly have been well studied in two model organisms, Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (for reviews, see references 5, 13, 36, and 58). The flagellum is composed of at least 25 different proteins that can be grouped into three physical parts: the basal body, the flagellar hook, and the filament. The basal body is imbedded within the cell envelope and works as a reversible rotary motor; the flagellar hook and filament extend outwards to the cell exterior and function as a universal joint and a propeller, respectively. The basal body is very complex and consists of several functional units: the membrane-supramembrane (MS)-C ring (rotor), the rod (driveshaft), the L-P rings (bushings), the stator (torque generator), and the flagellar export apparatus. The motor is driven by an inward-directed electrochemical gradient of protons or sodium. The torque generated by the motor is mechanically transmitted to the filament via the rod-hook complex, leading to the rotation of flagellar filament, which propels the bacterial cells forward.

Flagellar assembly is a sequential process (for reviews, see references 1 and 13). It begins with the MS ring assembly. Built onto the MS ring is a hollow rod that spans the periplasmic space. After formation of the MS ring/rod complex, the FlgI and FlgH proteins assemble around the rod to form the P and L rings, respectively. The hook and filament proteins are subsequently assembled on the rod. The flagellar rod begins with the MS ring and stops at the flagellar hook. Thus, it needs to penetrate the peptidoglycan (PG) layer during flagellar formation. It has been postulated that FlgJ is essential for flagellar rod formation (25, 45), with the N-terminal domain (rod-capping) acting as a scaffold for rod assembly and the C-terminal domain functioning as a PG hydrolase (PGase), which makes a hole in the PG layer to allow rod penetration. In S. Typhimurium, flgJ null mutants are aflagellated and nonmotile, while mutants that do not express the PGase domain produce fewer flagella and show poor motility (25, 45). However, the PGase domain is absent in the FlgJ homologs from several bacterial phyla, including Alphaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria, and Epsilonproteobacteria and Spirochaetes (44). As there is only one domain, these homologs are referred to as “single-domain FlgJ.” The function of these FlgJ homologs remains unknown.

Spirochetes are a group of motile bacteria that have a unique morphology and are able to swim in highly viscous gel-like environments (for reviews, see references 11 and 31). It is believed that motility plays a critical role in the biology of spirochetes and in the processes of diseases caused by pathogenic spirochetes (9, 11, 16, 32, 55). Spirochetes swim by means of two rotating bundles of periplasmic flagella (PFs) that reside between the outer membrane and cell cylinder (23, 32, 38, 49). PFs are structurally similar to the flagella of other bacteria, as each consists of a basal body-motor complex, a hook, and a filament (27, 33, 34, 43). However, compared to E. coli and S. Typhimurium, the structure and assembly of PFs as well as the genetic regulation of PF biosynthesis are poorly understood in spirochetes, primarily due to their fastidious growth requirements and the paucity of genetic tools.

The spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi is the causative agent of Lyme disease, which is the most prevalent tick-borne disease in the United States (for reviews, see references 47, 53, and 54). B. burgdorferi is relatively long (10 to 20 μm) and thin (0.3 μm) and has a flat-wave shape (23). Approximately 7 to 11 PFs are subterminally attached at each cell end, and these organelles form a tight-fitting ribbon that wraps around the cell cylinder (12, 34). The PFs have both skeletal and motility functions (32, 38, 49); aflagellated mutants are nonmotile and rod-shaped, rather than having the flat-wave morphology. Motility is considered to be an important virulence factor of B. burgdorferi since motility-defective mutants fail to invade human tissues and establish mammalian infection (32, 48). Due to its medical importance and recent advances in genetic manipulations of B. burgdorferi (47, 52), this organism has recently emerged as a model system to study the genetic regulation, structure, and assembly of PFs, as well as chemotaxis in spirochetes (11, 12, 32, 34, 39, 41, 49, 60). In this report, a single-domain FlgJ homolog (FlgJBb) was identified in the genome of B. burgdorferi. We studied its role in motility and flagellation using genetic, biochemical, and structural approaches. The results indicate that the role of FlgJBb in motility and flagellar assembly is unique and it is different from its counterparts from the enteric bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

High-passage avirulent Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto strain B31A (wild type) and its isogenic mutants were grown in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly II (BSK-II) liquid medium or on semisolid agar plates at 34°C in the presence of 3.4% carbon dioxide as previously described (32, 51).

Construction of an flgJBb deletion mutant and its complemented strain.

A method described previously was used to construct an flgJBb (bb0858) deletion mutant (32, 56). Briefly, a DNA fragment containing the entire flgJBb gene was PCR amplified with primers P1/P2 (see Table 1 for primer sequences), and the resultant PCR product was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI). A-160 bp HindIII DNA fragment within the flgJBb gene was deleted and replaced by a 1.3-kb kanamycin resistance cassette (Kanr) which was amplified by primers P3/P4. The final construct (flgJBb::kan) was linearized and electroporated into competent B31A cells to inactivate the targeted gene. Transformants were selected on the semisolid agar plates containing kanamycin (300 μg/ml).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this studya

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Note |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | TTGCATCAATACTGGACTC | Inactivation, flgJBb, F |

| P2 | TTGAATTTTCAGATCCCTC | Inactivation, flgJBb, R |

| P3 | AAGCTTTAATACCCGAGCTTCAAG | kan cassette, F |

| P4 | AAGCTTTCAAGTCAGCGTAATGCT | kan cassette, R |

| P5 | TATCAGAGGTAGTTGGCGTC | aadA cassette, F |

| P6 | TGTCTAGCTTCAAGTATGACG | aadA cassette, R |

| P7 | CATATGGAAACCAAAATTAATTCAC | Complementation, F |

| P8 | CTGCAGTTATTTACTTTTTTGTAATTG | Complementation, R |

| P9 | GGATCCTAATACCCGAGCTTCAAG | Complementation, PflgB, F |

| P10 | CATATGACCTCCCTCATTTAAAATTGC | Complementation, PflgB, R |

| P11 | ACCCAATATCCTAAAACTTC | RT-PCR, bb0776, F |

| P12 | TGGCAGCTGTATAAATTCCT | RT-PCR, bb0775, R |

| P13 | ACATCTGGCAAAGCACAAGA | RT-PCR, bb0775, F |

| P14 | GTATTGTTGTGCAGTCATTC | RT-PCR, bb0774, R |

| P15 | ACTCAAAAGCTATTCAAACT | RT-PCR, bb0774, F |

| P16 | TGAATTGTTGCTTTTTACCT | RT-PCR, bb0773, R |

| P17 | CACAACAAGAATAAATGATG | RT-PCR, bb0773, F |

| P18 | GTTGAAGCTTTGTTTGTTTG | RT-PCR, bb0772, R |

| P19 | TGGAGGAAATTGATGGAAAC | RT-PCR, bb0772, F |

| P20 | TTAAATCGGCAAGGCCAAAG | RT-PCR, bb0858, R |

| P21 | GCCTTGCCGATTTAATTTAC | RT-PCR, bb0858, F |

| P22 | TAGCTTGTGTTCTCTTACTG | RT-PCR, bb0771, R |

| P23 | TCATCTGCTATGATTATGCCACC | qRT-PCR, flaA, F |

| P24 | AGAATAAGCATATTCCATGCCAT | qRT-PCR, flaA, R |

| P25 | CATATTCAGATGCAGACAGAGG | qRT-PCR, flaB, F |

| P26 | CCCTGAAAGTGATGCTGGTGTG | qRT-PCR, flaB, R |

| P27 | TTCTCGCCCTACTGATGCTC | qRT-PCR, flgE, F |

| P28 | CCGTTGCCACTAACTCCAAG | qRT-PCR, flgE, R |

| P29 | AACAGGAATTAACGAGGCTG | qRT-PCR, eno, F |

| P30 | AAATTGCATTAGCACCAAGC | qRT-PCR, eno, R |

| P31 | CACCATGGAAACCAAAATTAATTCAC | rFlgJBb, F |

| P32 | TTTACTTTTTTGTAATTG | rFlgJBb, R |

The underlined sequences are engineered restriction cut sites for DNA cloning. F, forward; R, reverse.

To complement the flgJBb mutant, the flgB promoter of B. burgdorferi (PflgB) (22) was first PCR amplified (primers P9/P10) with engineered BamHI and NdeI cut sites at its 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. Then, the intact flgJBb gene was PCR amplified (primers P7/P8) with engineered NdeI and PstI cut sites at its 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. Two fragments were fused together at the site of NdeI, and the resultant DNA fragment (PflgB-flgJBb) was confirmed by DNA sequencing analysis. The BamHI-PstI-digested PflgB-flgJBb fragment was further cloned into pKFSS1, a shuttle vector of B. burgdorferi (18), generating the complementation vector PflgBflgJ/pKFSS1. For complementation, PflgBflgJ/pKFSS1 was electroporated into competent flgJBb mutant cells, and transformants were selected with both kanamycin (300 μg/ml) and streptomycin (50 μg/ml).

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR.

Total RNA samples were prepared as previously described (49, 56). To produce cDNA, 300 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed using AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega). For reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), 1 μl of cDNA was PCR amplified with different pairs of primers using Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of flaA (primers P23/P24), flaB (primers P25/P26), and flgE (primers P27/P28) transcripts was carried out using iQ SYBR green Supermix and an MyiQ thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The transcript of the enolase gene (eno, bb0337, primers P29/P30) was used as an internal control to normalize the qPCR data as described before (49, 56). The results were expressed as threshold cycle (CT) value. All of the primers for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1.

Generation of FlgJBb antiserum.

The full-length flgJBb gene was PCR amplified (primers P31/P32) using Platinum pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The amplicon was cloned into the pET101/D expression vector (Invitrogen), which generates a six-histidine tag at the C terminus of FlgJBb. The resultant plasmid was transformed into BL21(DE3) cells. The expression of flgJBb was induced using 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG). The recombinant protein (rFlgJBb) was purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) under denaturing conditions as previously described (32, 56). The purified protein was dialyzed in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl at 4°C overnight. To produce an antiserum against FlgJBb, rats were first immunized with 1 mg of rFlgJBb during a 1-month period and then boosted (100 μg per rat) twice at weeks 6 and 7 (antiserum was manufactured by General Bioscience Corporation, Brisbane, CA).

Electrophoresis, Western blotting, and protein turnover assay.

Sodium-dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analyses were carried out as previously described (32, 56). B. burgdorferi cells were cultured at 34°C and harvested at approximately 108 cells/ml. Equal amounts of whole-cell lysates (10 to 20 μg) were separated on SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad). Immunoblots were probed with specific antibodies against various proteins, including FlaA, FlaB, FliG2, FlgE, DnaK, CheA1, and CheA2. DnaK was used as an internal loading control. Monoclonal antibodies to FlaB, FlaA, and DnaK were kindly provided by A. Barbour (University of California, Irvine, CA), B. Johnson (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA), and J. Benach (State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY), respectively. Polyclonal antibodies to FlgE, FliG2, CheA1, and CheA2 have been described in our previous publications (30, 32, 49). Immunoblots were developed using horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies or protein A (GE Healthcare UK Limited, Little Chalfont Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) with Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). The densitometry of immunoreactive proteins in the blots is used to determine the relative amounts of proteins as previously described (40, 49). Densitometry was measured using the Molecular Imager ChemiDoc XRS Imaging system (Bio-Rad). The protein turnover assay was carried out as previously described (40, 49). B. burgdorferi strains were first grown in BSK-II medium at 34°C. After the cell density reached 2 × 108 cells per ml, 2-ml cultures were added to 50 ml of fresh BSK-II medium containing spectinomycin (100 μg/ml), followed by incubation at 34°C. Samples (5 ml) were harvested and processed for Western blots at the indicated time points.

Bacterial swarm plate assay and motion tracking analysis.

Swarm plate analysis was conducted as previously described (30, 38). Briefly, 5 μl of culture (108 cells/ml) was spotted onto 0.35% agarose containing BSK-II medium diluted 1:10 with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) without divalent cations. Plates were incubated for 3 to 4 days at 34°C with 3.4% CO2. The diameter of the swarm ring was measured and recorded in millimeters. The wild-type B31A strain was used as a positive control, and a previously constructed nonmotile flaB mutant (38) was used as a negative control to determine the initial inoculum size. The velocity of B. burgdorferi cells was measured using a computer-based bacteria tracking system as described before (4, 30). The data were statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison at P values of <0.01.

Cryo-ET.

Cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) analysis of B. burgdorferi was carried out as described previously (33, 34). Briefly, the freshly prepared B. burgdorferi cells were deposited onto a glow-discharged holey carbon electron microscopic (EM) grid, blotted, and rapidly frozen in liquid ethane. The frozen-hydrated specimens were imaged at −170°C using a Polara G2 electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) equipped with a field emission gun and a 4-k by 4-k charge-coupled device (CCD) (16 megapixel) camera (TVIPS GmbH, Germany). The microscope was operated at 300 kV with a magnification of ×31,000. Low-dose single-axis tilt series were collected from each bacterium at −6 μm defocus with a cumulative dose of ∼100 e−/Å2 distributed over 65 images with an angular increment of 2°, covering a range from −64° to +64°. The tilt series images were aligned and reconstructed using the IMOD software package (28). In total, 47, 22, and 18 cryo-tomograms were reconstructed from the flgJBb deletion mutant, the complemented flgJBb strain, and the wild-type strain, respectively.

Subvolume averaging of flagellar motor and 3D visualization.

The subvolume processing of flagellar motors was carried out as previously described (33, 34). Briefly, the positions and orientations of each flagellar motor in each tomogram were determined manually. Volumes (256 by 256 by 256 pixels) containing entire flagellar motors were extracted from the original tomograms. In total, 321 flagellar motor volumes were extracted from 47 tomograms of flgJBb mutant cells and were further used to generate the three-dimensional (3D) structures. Tomographic reconstructions were visualized using IMOD. Reconstructions of several B. burgdorferi cells were segmented manually using the 3D modeling software Amira (Visage Imaging, Richmond, Australia). Three-dimensional segmentation of the flagella, outer membrane, and cytoplasmic membrane was manually constructed. The surface model from the averaged flagellar motor (33) was computationally mapped back into the original cellular context.

RESULTS

Identification of an FlgJ homolog.

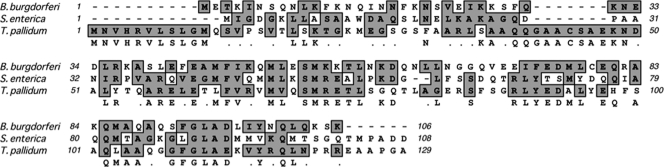

The homolog of flgJ was not annotated when the genome of the B. burgdorferi B31 strain was released (19). In the study of the rpoS gene (bb0771) (19, 61), a misidentified putative open reading frame (orf) was found between the rpoS and flgI (bb0772) genes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Recently, Lybecker and Samuels and Burtnick et al. also found this orf (10, 35). The identified orf (bp 813706 to 813386) was designated bb0858 when the genome of the B31 strain was updated. BB0858 consists of 106 amino acids, and its predicted molecular mass is 12.4 kDa. A BLAST search showed that BB0858 is a homolog of FlgJ proteins. It has 30% identity and 54% similarity to the rod-capping domain of S. Typhimurium FlgJ and 33% identity and 55% similarity to Treponema pallidum FlgJ. The S. Typhimurium FlgJ protein consists of 316 amino acids, and its molecular mass is approximately 37 kDa (45). Sequence alignment revealed that BB0858 is much smaller than that of S. Typhimurium FlgJ, and it lacks the C-terminal PGase domain (Fig. 1), which indicates that BB0858 belongs to the family of single-domain FlgJ proteins. Here, BB0858 is called FlgJBb.

Fig 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of FlgJ proteins. The numbers show the positions of amino acids in the FlgJ proteins from B. burgdorferi, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, and T. pallidum. For the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium FlgJ, only the N-terminal rod-capping domain is included. GenBank accession numbers for the aligned proteins are as follows: S. enterica serovar Typhimurium FlgJ (NP_460153) and T. pallidum FlgJ (NP_219396). The alignment was carried out using the program MacVector 10.6.

Isolation and characterization of an flgJBb mutant and its complemented strain.

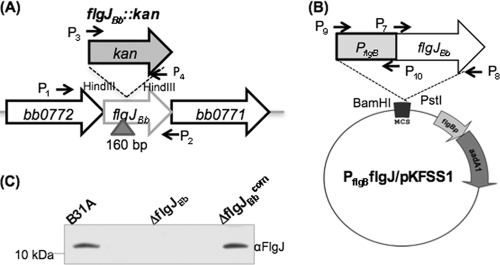

To study the role of FlgJBb in the motility and flagellation of B. burgdorferi, the cognate gene (bb0858) was inactivated by targeted mutagenesis as illustrated in Fig. 2A. A total of 5 kanamycin-resistant colonies appeared on the agar plates after 15 days of incubation. PCR analysis showed that three colonies had kan inserted into the flgJBb locus as expected (data not shown). One clone was further confirmed by Western blotting using a specific antibody against FlgJBb, and the result showed that FlgJBb was abolished in this clone (Fig. 2C). The obtained clone is designated ΔflgJBb. This mutant was then genetically complemented using PflgBflgJ/pKFSS1 (Fig. 2B). The complementation successfully restored the expression of FlgJBb (Fig. 2C). The ΔflgJBb mutant and one complemented clone (ΔflgJBbcom) were used for further characterizations as described below.

Fig 2.

Constructing the flgJBb mutant and its complemented strain. (A and B) Diagrams illustrating the construction of the flgJBb mutant and its complemented strain. The vector flgJBb::kan was used to construct the flgJBb mutant and the plasmid PflgBflgJ/pKFSS1 was used to complement the mutant. Arrows indicate the relative positions of PCR primers for constructing these plasmids, and the sequences of these primers are listed in Table 1. “Δ” shows the DNA fragments deleted from the gene, and the numbers are the sizes of deleted DNA fragments. (C) Western blot analysis of the flgJBb mutant (ΔflgJBb) and its complemented strain (ΔflgJBbcom). Similar amounts of whole-cell lysates from B31A, ΔflgJBb, and ΔflgJBbcom strains were analyzed on SDS-PAGE and then probed using a specific antibody against FlgJBb. Immunoblots were developed using horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody with an ECL luminol assay as previously described (32, 56).

The ΔflgJBb mutant is partially defective in motility.

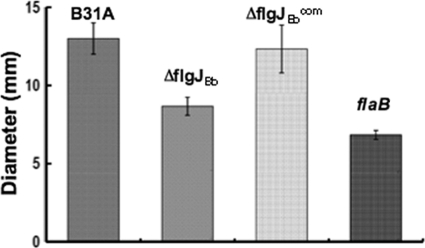

The swimming behaviors of ΔflgJBb were detected by dark-field microscopy. Within the normal BSK-II medium, the mutant is almost undistinguishable to the wild type, as B. burgdorferi poorly displaces in low viscous media (23). In 1% methylcellulose, which represents a highly viscous environment (6), the wild type substantially accelerated its swimming speed and its average velocity was approximately 9.4 ± 0.6 μm/s. In contrast, the ΔflgJBb mutant swam slower than the wild type and its average velocity was 7.2 ± 0.8 μm/s, indicating that the motility of the mutant was slightly impacted. This proposition was further confirmed by the swarm plate assay in which the ring formed by the mutant (9 mm) is significantly smaller (P < 0.01) than that of the wild type (13 mm), but it is larger than that of a nonmotile flaB mutant of B. burgdorferi (7 mm) (Fig. 3). In contrast, the motility was fully restored in the ΔflgJBbcom strain (average velocity = 10.0 ± 1.7 μm/s; swarm ring diameter of 12.5 mm). Taken together, these results indicate that the ΔflgJBb mutant is partially defective in motility.

Fig 3.

Swarm plate assay of B31A, ΔflgJBb, and ΔflgJBbcom strains. The assays were carried out on 0.35% agarose containing 1:10 diluted BSK-II medium as previously described (30, 38). The flaB mutant, a previously constructed nonmotile mutant (38), is included to determine the size of the inoculum. The data are presented as mean diameters (in millimeters) of swarms plus or minus the standard errors from five plates.

The ΔflgJBb mutant has abnormal PFs.

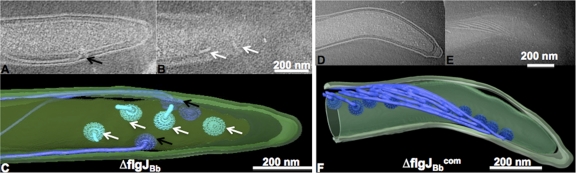

Cryo-ET was conducted to reveal if the ΔflgJBb mutant has any defect in the structure of PFs. For the wild type, a total of 167 PFs were observed in 18 examined cells (average number of PFs per cell was 9.3 ± 2.0; see details in Table 2). These observed PFs consisted of basal bodies, flagellar hooks, and filaments, and all of the observed PFs oriented toward the middle of the cell bodies (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). For the ΔflgJBb mutant, a total of 255 PFs were detected in 31 cells (8.2 ± 1.3 PFs per cell). While the mutant has a similar number of flagella as the wild type, the observed PFs appeared very diverse (Fig. 4A; see also Movie S1 in the supplemental material), including intact PFs, abnormal PFs (i.e., PFs lacking filaments or with short filaments, PFs without flagellar hooks or with truncated hooks), and disoriented PFs (PFs directed to the cell pole instead of toward the middle of the cell body) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). These abnormal PFs were evident in all examined cells (average abnormal PFs per cell is 2.4 ± 1.4), and they accounted for 29% of the total observed PFs (74 out of 255 PFs). For the ΔflgJBbcom strain, 22 cells were examined and a total of 215 PFs were observed (9.7 ± 1.5 PFs per cell), and no abnormal PFs were evident (Fig. 4B; see also Movie S2 in the supplemental material). These results indicate that FlgJBb is involved in the synthesis and/or assembly of the flagellar hooks and filaments in B. burgdorferi.

Table 2.

The ΔflgJBb mutant has defective PFs

| Strain | No. of cells | Total visible PFs | Total defective PFsa | Defective PFs/cell |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B31A | 18 | 167 | 0 | 0 |

| ΔflgJBb | 31 | 255 | 74b | 2.4 ± 1.4 |

| ΔflgJBbcom | 22 | 215 | 0 | 0 |

Includes the PFs lacking filaments, PFs with truncated filaments, PFs with short flagellar hooks, and disoriented PFs (PFs directed to the cell poles instead of toward the middle of the cell bodies).

The defective PFs are evident in all 31 examined mutant cells.

Fig 4.

Cryo-ET analysis of the ΔflgJBb mutant. The left panel shows two sections of 3D reconstruction (A and B) and the surface rendering of a corresponding 3D reconstruction (C) from the ΔflgJBb mutant. The right panel shows two sections of 3D reconstruction (D and E) and the surface rendering of a corresponding 3D reconstruction (F) from the ΔflgJBbcom strain. Abnormal PFs are indicated by white arrows, and intact PFs (including the motor, hook, and filament) are labeled by black arrows.

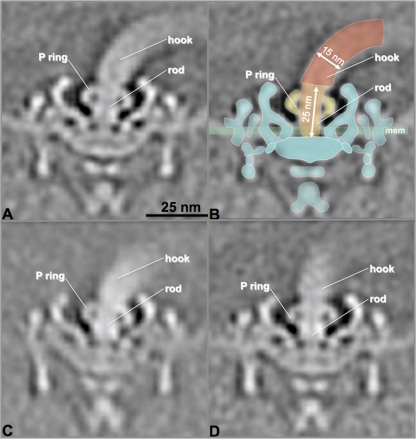

The ΔflgJBb mutant has intact flagellar basal bodies.

Tomographic subvolume averaging was utilized to dissect the architecture of flagellar basal bodies in the ΔflgJBb mutant cells. We found that the observed defects described above primarily occurred at flagellar hooks and filaments. There was no defect evident in any part of the flagellar basal bodies, including the MS-C ring, the rod, the P ring, the stator, and the flagellar export apparatus (Fig. 5), indicating that the basal bodies remained intact in the mutant. We are particularly interested in the structure of flagellar rods, as previous studies from S. Typhimurium conclude that FlgJ is essential for rod formation (25, 36, 45). However, we found that the flagellar rods were intact in all types of PFs observed in the mutant cells, including the intact PFs (Fig. 5A), the PFs without filaments (Fig. 5C), and the PFs with truncated hooks (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these results indicate that FlgJBb is not required for the assembly of the rod. Instead, it is linked to the formation of flagellar hooks and filaments in B. burgdorferi.

Fig 5.

The ΔflgJBb mutant has intact flagellar basal bodies. The asymmetric flagellar motor reconstructions from three types of flagella in the ΔflgJBb mutant, including intact PF (A), defective PF lacking filament (C), and defective PF with truncated hook (D). Intact basal bodies were evident in all three types of flagella in the mutant. (B) A flagellar model was overlaid on the image from panel A. The hook, rod, P ring, and cytoplasmic membrane (mem) are labeled. The numbers are the length of the rod (25 nm) and diameter of hook (15 nm).

The accumulations of FlgE and FlaB are decreased in the ΔflgJBb mutant.

The flagellar hook and filament of B. burgdorferi are primarily composed of FlgE and FlaB, respectively (19, 38, 49). We hypothesized that the defects observed in the ΔflgJBb mutant are probably due to decreases in FlgE and FlaB. To test this hypothesis, quantitative immunoblots were carried out to compare the levels of FlgE and FlaB between the wild type and the mutant. The results showed that the accumulations of FlgE and FlaB in the mutant were decreased by approximately 54% and 72%, respectively (Fig. 6). The levels of other flagellar and chemotaxis proteins remained unchanged, including FliG2 (a motor switch complex protein), FlaA (a minor flagellin protein), and CheA1/CheA2 (chemotaxis proteins) (Fig. 6). These results indicate that the inactivation of flgJBb reduces the accumulation of FlaB and FlgE in the mutant.

Fig 6.

The accumulations of FlaB and FlgE were decreased in the ΔflgJBb mutant. Similar amounts of whole-cell lysates of B31A, ΔflgJBb, and ΔflgJBbcom strains were analyzed on SDS-PAGE. The presence of FlaA, FlaB, FlgE, FliG2, CheA1, CheA2, and DnaK were detected using specific antibodies against these proteins. DnaK was used as a loading control as previously described (49). Immunoblots were developed as described in the legend to Fig. 2C.

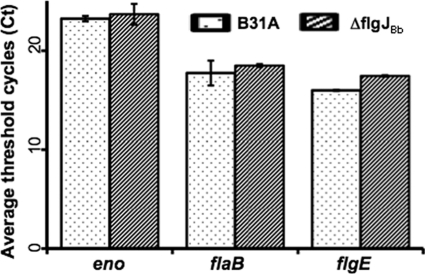

Decreases of FlgE and FlaB in the ΔflgJBb mutant occur at the posttranscriptional level.

To reveal the potential mechanism underlying the decreases of FlgE and FlaB in the ΔflgJBb mutant, qRT-PCR was carried out to measure the levels of flgE and flaB transcripts. Using the enolase (eno, bb0337) (19) transcript as an internal control, the relative levels of flgE and flaB transcripts were compared between the mutant and wild type. It was found that the levels of flgE and flaB transcripts remained unchanged in the ΔflgJBb mutant (Fig. 7), indicating that the reduction of FlgE and FlaB in the mutant does not occur at the transcriptional level.

Fig 7.

Comparison of the flaB and flgE mRNA levels between the wild type and the ΔflgJBb mutant. The levels of flaB and flgE transcripts were measured by qRT-PCR as previously described (49, 56). The transcript of the enolase gene (eno) was used as an internal control to normalize the qPCR data. The results were expressed as the mean threshold cycles (CT) of triplicate samples.

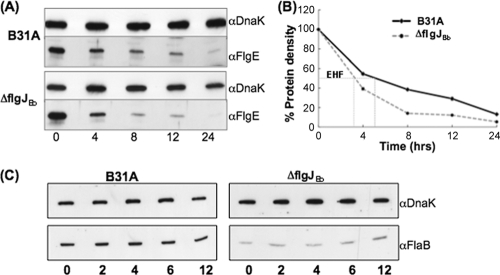

The ΔflgJBb mutant has a faster turnover rate of FlgE but not FlaB.

As the levels of flgE and flaB transcripts remain unchanged in the ΔflgJBb mutant, the reduction of FlgE and FlaB accumulations could result either from protein turnover or from translational inhibition. To rule out one of these two possibilities, spectinomycin was added to growing cells of the wild type and the ΔflgJBb mutant to arrest protein translation, and then the levels of FlgE and FlaB were measured at various times over a 12-hour period. It was found that although FlgE was not stable in either the wild type or the ΔflgJBb mutant, its turnover rate in the mutant was significantly (P < 0.01) accelerated (Fig. 8A and B). The estimated half-life of FlgE in the wild type was 5 h, and it was decreased to approximately 3 h in the mutant (Fig. 8B), suggesting that the reduction of FlgE in the mutant is, at least in part, due to protein degradation. In the ΔflgJBb mutant, the FlaB level was dramatically decreased. However, such a decrease is not subject to protein turnover, as the stability of FlaB remained stable over 12 h in the mutant (Fig. 8C). As no obvious turnover was observed, translational control apparently accounts for the decease of FlaB in the ΔflgJBb mutant.

Fig 8.

Detecting the stability of FlaB (C) and FlgE (A). Protein translation was arrested by adding spectinomycin (100 μg/ml) to the cultures of B31A and the ΔflgJBb mutant. Samples were withdrawn at the indicated time points and analyzed by immunoblotting. The results are expressed as the percent protein density at zero time compared to subsequent time samples (B). Gels were loaded with the whole-cell lysates of B31A (10 μg) and the ΔflgJBb mutant (20 μg), transferred to a PVDF membrane, and finally probed with antibodies against FlaB, FlgE, and DnaK. DnaK was used as a sample loading control. EHF represents the estimated half-life.

DISCUSSION

FlgJ homologs are present in many bacteria (44). However, their functions in flagellation and motility have only been studied in S. Typhimurium and Rhodobacter sphaeroides (14, 24, 25, 45). S. Typhimurium FlgJ (FlgJSe) is a dual domain protein which contains the N-terminal rod-capping domain and C-terminal PGase domain, whereas the R. sphaeroides FlgJ (FlgJRs) only has the rod-capping domain. In both S. Typhimurium and R. sphaeroides, the flgJ null mutants are aflagellated and nonmotile. However, we report here that the influence of FlgJBb on the flagellation and motility of B. burgdorferi is not substantial. First, cryo-ET analyses disclosed that only approximately one-third (74 out of 255) of the PFs observed in the ΔflgJBb mutant had defects and the rest were intact (Fig. 4 and Table 2). Second, bacterial tracking analysis and swarm plate assays showed that the motility of the mutant was slightly decreased compared to that of the wild type (Fig. 3). Finally, immunoblot analysis revealed that only the accumulation of flagellar hook protein FlgE and flagellin protein FlaB were decreased in the mutant, whereas other flagellar proteins remained unchanged (Fig. 6). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the function of FlgJBb in B. burgdorferi is unique and it is different from its counterparts of S. Typhimurium and R. sphaeroides.

The flagellar rod not only acts as a driveshaft that transmits the mechanical torque from the motor to the hook and filament but also is a key component of the flagella export apparatus (a type III secretion system; T3SS) (5, 17, 36). In the paradigm models of E. coli and S. Typhimurium, the flagellar rod is composed of at least four proteins, including FlgB, FlgC, FlgF (proximal rod), and FlgG (distal rod) (26, 36). Of these four proteins, three have been annotated in the genome of B. burgdorferi (19): BB0294 (FlgB), BB0293 (FlgC), and BB0774 (FlgG). These three homologs are well conserved and have 27%, 38%, and 50% identities to their counterparts from the enteric bacteria, respectively. Interestingly, no FlgF homolog has been annotated in the genome of B. burgdorferi (19). However, an in silico genome search revealed that BB0775 (FlhO) has 30% identity and 49% similarity to the FlgF of E. coli, suggesting that FlhO may play a role similar to FlgF. In addition, FliE is often considered a part of the rod (42). It has been postulated that FliE forms a substructure between the MS ring and the rod and serves as an initial point for the rod assembly (13, 36). A homolog of FliE (BB0292) is also identified in the genome of B. burgdorferi (19). Thus, the flagellar rod of B. burgdorferi has protein components similar to its counterpart in enteric bacteria.

FlgJ is often considered to be the fifth protein of the rod (25, 36, 45). It is a bifunctional protein that has both the PGase activity and binding affinity to other rod proteins. In S. Typhimurium, FlgJSe physically interacts with several other rod proteins, in particular FliE and FlgB, via its N-terminal rod-capping domain (25). Genetic and structural analyses demonstrate that the mutants without the rod-capping domain fail to assemble the rod, the P ring, the hook, and the filament; only the MS ring is evident in the mutants. All of these mutants are motility deficient. Based on these observations, it has been proposed that the N-terminal rod-capping domain is directly involved in rod formation by serving as a scaffold for the rod assembly, which is essential for the flagellation and motility. However, the evidence reported here does not support this proposition, as the ΔflgJBb mutant still assembled intact flagellar basal bodies (i.e., the MS ring, the rod, and the P ring) (Fig. 5).

The C-terminal PGase domain of FlgJSe is believed to locally digest the PG layer and permit penetration of the nascent rod (45). Consistent with this model, the mutants with a defective PGase domain but with a normal rod-capping domain produce defective basal bodies that lack the L ring and hook. In situ cryo-ET studies of several spirochetes (e.g., T. pallidum and Treponema primitia) have demonstrated that the PFs are located between the outer membrane and the PG layer (12, 27, 33, 34, 43), reflecting that the nascent flagellar rods have to penetrate the PG layer before the intact PFs are assembled. Similar to FlgJBb, the FlgJ homologs in other sequenced spirochetes also belong to the family of single-domain FlgJ; they all lack the C-terminal PGase domain, suggesting that the spirochetes may have evolved another route to process the passage of elongating rods through the PG layer. It has been postulated that the class of dual-domain FlgJ proteins has evolved by merging two individual domains together (44). Consistent with this assumption, the absent PGase domain has been identified in the genome of R. sphaeroides, which is encoded by an independent gene (14). It interacts with FlgJRs and is required for the assembly of the flagella. Thus, a similar scenario may exist in spirochetes. In addition, most bacteria produce multiple PG hydrolases (e.g., amidases), which are capable of cleaving the PG layer during cell growth and division (for a review, see reference 57). Yang et al. recently identified a putative amidase in B. burgdorferi (62). The gene (bb0666) encoding this enzyme is located in the same operon as flaA, a gene encoding a flagellar filament sheath protein. It is possible that this enzyme may have the PGase activity and digest the PG layer of B. burgdorferi cells to permit the penetration of the rods.

Besides acting as a flexible linker coupling the motor to the filament, completion of the flagellar hook structure often serves as a checkpoint for transcriptional control of flagellar synthesis (15, 50, 59). In E. coli and S. Typhimurium, upon the completion of the hook, the hook-basal body complex provides an export route for FlgM, an antagonist of FliA (3, 13, 17, 37). As FlgM exits the cell, FliA, a flagellum-specific σ28 transcription factor, is free to initiate the transcription of the class 3 genes (the genes encoding flagellin and chemotaxis proteins). In the flgE mutants, the transcription of class 3 genes is turned off due to the accumulation of intracellular FlgM. In the transcriptional hierarchy, flgE belongs to the class 2 genes, and it is controlled by a σ70 transcription factor. Besides the transcriptional regulation, FlgE is also posttranscriptionally regulated in response to the stage of flagellar assembly (7, 8, 29). FlgE accumulation is almost completely abrogated in the null mutant of flgJSe, but the level of flgE transcript remains unchanged (8). We found that the ΔflgJBb mutant still produced FlgE, but the accumulation of FlgE was substantially decreased. Furthermore, we showed that the decrease of FlgE does not occur at the transcriptional level (Fig. 7) but is instead due to rapid protein turnover (Fig. 8). Based on these results, we propose that the degradation of FlgE has been accelerated in the ΔflgJBb mutant and the decreased level of FlgE can account, at least in part, for the defective hooks observed in the ΔflgJBb mutant (the attenuated FlgE in the mutant cells is insufficient to produce intact hooks).

The FlgE subunits are exported via T3SS after the rod assembly is completed and then begin to polymerize on the distal end of the rod (13, 17). For the external flagellated bacteria, the assembly of the hook primarily occurs outside the cells. In contrast, spirochetes have endoflagella, which are located between the outer membrane and the PG layer (11, 12, 33, 34). Thus, during the hook assembly, the FlgE subunits have to encounter a variety of periplasmic enzymes. Some of these enzymes (e.g., proteases) have proteolytic activity and may degrade the FlgE proteins. Thus, spirochetes may have evolved certain routes to protect the FlgE subunits from proteolysis in the periplasmic space. Consistent with this speculation, the protein turnover assay revealed that the FlgE protein is not stable and can be degraded in B. burgdorferi (Fig. 8A). The FlgE degradation was accelerated in the ΔflgJBb mutant (Fig. 8B), indicating that FlgJBb likely functions as a chaperone of FlgE by increasing the stability of FlgE in the periplasmic space of B. burgdorferi cells. In addition, FlgN, a T3SS chaperone, protects two hook-associated proteins, FlgK and FlgL, of S. Typhimurium from proteolysis before they are secreted outside the cells (2, 20). Alternatively, FlgJBb may play a similar role as FlgN by protecting the FlgE subunits from proteolysis before it is exported outside the cytoplasm. A recent report describes that the FlgE subunits of B. burgdorferi are cross-linked and form a high-molecular-weight complex (49). It is also possible that the crossed-linked FlgE may be protected from proteolysis, and the presence of FlgJBb may facilitate the FlgE cross-linking and consequently increases the stability of FlgE in the periplasmic space. In future studies, we will attempt to narrow down the potential mechanism involved.

Sal et al. report that the hook structure is essential for the accumulation of flagellin proteins FlaA and FlaB of B. burgdorferi. The levels of these two proteins are reduced by approximately 70% to 85% in the flgE deletion mutant (49). Here, we also found that the FlaB accumulation was substantially decreased in the ΔflgJBb mutant. This result is expected, as FlaB is exported via the hook-basal body complex. In the ΔflgJBb mutant, the hook structure was partially disrupted, which could slow down the export of FlaB. In the flgE mutant of B. burgdorferi, the decrease of FlaB occurs at the translational level (49). A similar result was observed in the ΔflgJBb mutant, whereas the FlaB level was substantially decreased, its stability remained unchanged (Fig. 8C). Sze et al. recently reported that CsrA (a carbon storage regulatory protein) binds to the untranslated leader sequence of the flaB transcript and blocks the translation of FlaB (56a). It is possible that the inactivation of flgJBb somehow increases the level of CsrA, which in turn represses the translation of FlaB in the mutant.

FlaA is a minor flagellin protein of B. burgdorferi (21). Previous studies have shown that FlaA interacts with FlaB. The presence of FlaB is essential for the stability of FlaA; in the flaB mutant, the level of FlaA is decreased by more than 85% and such decrease is due to protein turnover (40, 49). It is very interesting to observe that the level of FlaA remained unchanged in the ΔflgJBb mutant (Fig. 6), and the protein turnover assay showed that FlaA is very stable in the mutant (data not shown). As a filament sheath protein, FlaA is not exported via T3SS. It is believed that FlaA is secreted via the sec-dependent pathway (11, 31, 46). Thus, the secretion of FlaA should not be influenced by the defective hooks in the ΔflgJBb mutant. In addition, the amount of FlaA is less than 20% of FlaB (40). In the ΔflgJBb mutant, the FlaB accumulation was decreased by approximately 70%. Thus, it is possible that the remaining FlaB is sufficient to interact with FlaA and protect FlaA from protein turnover.

In summary, the results presented here show that the role of FlgJBb, a class of single-domain FlgJ proteins, is unique and that it is different from its counterparts from other bacteria. In addition, the analysis of the ΔflgJBb mutant has provided important insight into the regulation of flagellar synthesis in B. burgdorferi. This study has further reinforced the idea that the spirochete has evolved a unique mechanism to regulate flagellar synthesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Norgard and F. Yang for sharing the flgJ gene sequence information. We also thank A. Barbour and J. Benach for providing antibodies.

This research was supported by Public Health Service grants AI078958, AI078958S1, and DE019667 to C. Li and AI087946 and Welch Foundation grant AU-1714 to J. Liu.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 December 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aldridge P, Hughes KT. 2002. Regulation of flagellar assembly. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aldridge P, Karlinsey J, Hughes KT. 2003. The type III secretion chaperone FlgN regulates flagellar assembly via a negative feedback loop containing its chaperone substrates FlgK and FlgL. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1333–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aldridge PD, et al. 2006. The flagellar-specific transcription factor, sigma28, is the type III secretion chaperone for the flagellar-specific anti-sigma28 factor FlgM. Genes Dev. 20:2315–2326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bakker RG, Li C, Miller MR, Cunningham C, Charon NW. 2007. Identification of specific chemoattractants and genetic complementation of a Borrelia burgdorferi chemotaxis mutant: flow cytometry-based capillary tube chemotaxis assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1180–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berg HC. 2003. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72:19–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berg HC, Turner L. 1979. Movement of microorganisms in viscous environments. Nature 278:349–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bonifield HR, Hughes KT. 2003. Flagellar phase variation in Salmonella enterica is mediated by a posttranscriptional control mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 185:3567–3574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonifield HR, Yamaguchi S, Hughes KT. 2000. The flagellar hook protein, FlgE, of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is posttranscriptionally regulated in response to the stage of flagellar assembly. J. Bacteriol. 182:4044–4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Botkin DJ, et al. 2006. Identification of potential virulence determinants by Himar1 transposition of infectious Borrelia burgdorferi B31. Infect. Immun. 74:6690–6699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burtnick MN, et al. 2007. Insights into the complex regulation of rpoS in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 65:277–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Charon NW, Goldstein SF. 2002. Genetics of motility and chemotaxis of a fascinating group of bacteria: the spirochetes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36:47–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Charon NW, et al. 2009. The flat-ribbon configuration of the periplasmic flagella of Borrelia burgdorferi and its relationship to motility and morphology. J. Bacteriol. 191:600–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chevance FF, Hughes KT. 2008. Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:455–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de la Mora J, Ballado T, Gonzalez-Pedrajo B, Camarena L, Dreyfus G. 2007. The flagellar muramidase from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 189:7998–8004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DePamphilis ML, Adler J. 1971. Fine structure and isolation of the hook-basal body complex of flagella from Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 105:384–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dunham-Ems SM, et al. 2009. Live imaging reveals a biphasic mode of dissemination of Borrelia burgdorferi within ticks. J. Clin. Invest. 119:3652–3665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erhardt M, Namba K, Hughes KT. 2010. Bacterial nanomachines: the flagellum and type III injectisome. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frank KL, Bundle SF, Kresge ME, Eggers CH, Samuels DS. 2003. aadA confers streptomycin resistance in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 185:6723–6727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fraser CM, et al. 1997. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390:580–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fraser GM, Bennett JC, Hughes C. 1999. Substrate-specific binding of hook-associated proteins by FlgN and FliT, putative chaperones for flagellum assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 32:569–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ge Y, Li C, Corum L, Slaughter CA, Charon NW. 1998. Structure and expression of the FlaA periplasmic flagellar protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 180:2418–2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ge Y, Old IG, Saint GI, Charon NW. 1997. Molecular characterization of a large Borrelia burgdorferi motility operon which is initiated by a consensus sigma70 promoter. J. Bacteriol. 179:2289–2299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goldstein SF, Charon NW, Kreiling JA. 1994. Borrelia burgdorferi swims with a planar waveform similar to that of eukaryotic flagella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:3433–3437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. González-Pedrajo B, de la Mora J, Ballado T, Camarena L, Dreyfus G. 2002. Characterization of the flgG operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8 and its role in flagellum biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1579:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hirano T, Minamino T, Macnab RM. 2001. The role in flagellar rod assembly of the N-terminal domain of Salmonella FlgJ, a flagellum-specific muramidase. J. Mol. Biol. 312:359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Homma M, Kutsukake K, Hasebe M, Iino T, Macnab RM. 1990. FlgB, FlgC, FlgF and FlgG. A family of structurally related proteins in the flagellar basal body of Salmonella Typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 211:465–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Izard J, et al. 2009. Cryo-electron tomography elucidates the molecular architecture of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. J. Bacteriol. 191:7566–7580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. 1996. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116:71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee HJ, Hughes KT. 2006. Posttranscriptional control of the Salmonella enterica flagellar hook protein FlgE. J. Bacteriol. 188:3308–3316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li C, et al. 2002. Asymmetrical flagellar rotation in Borrelia burgdorferi nonchemotactic mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:6169–6174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li C, Motaleb A, Sal M, Goldstein SF, Charon NW. 2000. Spirochete periplasmic flagella and motility. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:345–354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li C, Xu H, Zhang K, Liang FT. 2010. Inactivation of a putative flagellar motor switch protein FliG1 prevents Borrelia burgdorferi from swimming in highly viscous media and blocks its infectivity. Mol. Microbiol. 75:1563–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu J, et al. 2010. Cellular architecture of Treponema pallidum: novel flagellum, periplasmic cone, and cell envelope as revealed by cryo electron tomography. J. Mol. Biol. 403:546–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu J, et al. 2009. Intact flagellar motor of Borrelia burgdorferi revealed by cryo-electron tomography: evidence for stator ring curvature and rotor/C-ring assembly flexion. J. Bacteriol. 191:5026–5036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lybecker MC, Samuels DS. 2007. Temperature-induced regulation of RpoS by a small RNA in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1075–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Macnab RM. 2003. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:77–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCarter LL. 2006. Regulation of flagella. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:180–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Motaleb MA, et al. 2000. Borrelia burgdorferi periplasmic flagella have both skeletal and motility functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:10899–10904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Motaleb MA, et al. 2005. CheX is a phosphorylated CheY phosphatase essential for Borrelia burgdorferi chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 187:7963–7969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Motaleb MA, Sal MS, Charon NW. 2004. The decrease in FlaA observed in a flaB mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi occurs posttranscriptionally. J. Bacteriol. 186:3703–3711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Motaleb MA, Sultan SZ, Miller MR, Li C, Charon NW. 2011. CheY3 of Borrelia burgdorferi is the key response regulator essential for chemotaxis and forms a long-lived phosphorylated intermediate. J. Bacteriol. 193:3332–3341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Müller V, Jones CJ, Kawagishi I, Aizawa S, Macnab RM. 1992. Characterization of the fliE genes of Escherichia coli and Salmonella Typhimurium and identification of the FliE protein as a component of the flagellar hook-basal body complex. J. Bacteriol. 174:2298–2304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murphy GE, Leadbetter JR, Jensen GJ. 2006. In situ structure of the complete Treponema primitia flagellar motor. Nature 442:1062–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nambu T, Inagaki Y, Kutsukake K. 2006. Plasticity of the domain structure in FlgJ, a bacterial protein involved in flagellar rod formation. Genes Genet. Syst. 81:381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nambu T, Minamino T, Macnab RM, Kutsukake K. 1999. Peptidoglycan-hydrolyzing activity of the FlgJ protein, essential for flagellar rod formation in Salmonella Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 181:1555–1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Norris SJ, Charon NW, Cook RG, Fuentes MD, Limberger RJ. 1988. Antigenic relatedness and N-terminal sequence homology define two classes of periplasmic flagellar proteins of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum and Treponema phagedenis. J. Bacteriol. 170:4072–4082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rosa PA, Tilly K, Stewart PE. 2005. The burgeoning molecular genetics of the Lyme disease spirochaete. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:129–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sadziene A, Thomas DD, Bundoc VG, Holt SC, Barbour AG. 1991. A flagella-less mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi. Structural, molecular, and in vitro functional characterization. J. Clin. Invest. 88:82–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sal MS, et al. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi uniquely regulates its motility genes and has an intricate flagellar hook-basal body structure. J. Bacteriol. 190:1912–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Samatey FA, et al. 2004. Structure of the bacterial flagellar hook and implication for the molecular universal joint mechanism. Nature 431:1062–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Samuels DS. 1995. Electrotransformation of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:253–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Samuels DS. 2011. Gene regulation in Borrelia burgdorferi. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65:479–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. 2011. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60103-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L. 2004. The emergence of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1093–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sultan SZ, Pitzer JE, Miller MR, Motaleb MA. 2010. Analysis of a Borrelia burgdorferi phosphodiesterase demonstrates a role for cyclic-di-guanosine monophosphate in motility and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 77:128–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sze C, Li C. 2011. Inactivation of bb0184 that encodes a carbon storage regulator A represses the infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 79:1270–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56a. Sze C, et al. Mol. Microbiol., in press [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vollmer W, Joris B, Charlier P, Foster S. 2008. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:259–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2004. Making sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:1024–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wagenknecht T, Derosier DJ, Aizawa S, Macnab RM. 1982. Flagellar hook structures of Caulobacter and Salmonella and their relationship to filament structure. J. Mol. Biol. 162:69–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Xu H, Raddi G, Liu J, Charon NW, Li C. 2011. Chemoreceptors and flagellar motors are subterminally located in close proximity at the two cell poles in spirochetes. J. Bacteriol. 193:2652–2656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yang XF, et al. 2005. Analysis of the ospC regulatory element controlled by the RpoN-RpoS regulatory pathway in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 187:4822–4829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yang Y, Li C. 2009. Transcription and genetic analyses of a putative N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase in Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 290:164–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.