Abstract

Objective To review the effectiveness and safety of clinical officers (healthcare providers trained to perform tasks usually undertaken by doctors) carrying out caesarean section in developing countries compared with doctors.

Design Systematic review with meta-analysis.

Data sources Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, BioMed Central, the Reproductive Health Library, and the Science Citation Index (inception-2010) without language restriction.

Study selection Controlled studies.

Data extraction Information was extracted from each selected article on study characteristics, quality, and outcome data. Two independent reviewers extracted data.

Results Six non-randomised controlled studies (16 018 women) evaluated the effectiveness of clinical officers carrying out caesarean section. Meta-analysis found no significant differences between the clinical officers and doctors for maternal death (odds ratio 1.46, 95% confidence interval 0.78 to 2.75; P=0.24) or for perinatal death (1.31, 0.87 to 1.95; P=0.19). The results were heterogeneous, with some studies reporting a higher incidence of both outcomes with clinical officers. Clinical officers were associated with a higher incidence of wound infection (1.58, 1.01 to 2.47; P=0.05) and wound dehiscence (1.89, 1.21 to 2.95; P=0.005). Two studies accounted for confounding factors.

Conclusion Clinical officers and doctors did not differ significantly in key outcomes for caesarean section, but the conclusions are tentative owing to the non-randomised nature of the studies. The increase in wound infection and dehiscence may highlight a particular training need for clinical officers.

Introduction

Many developing countries have a shortage of trained doctors. Rural areas are particularly affected, as doctors predominantly congregate in urban areas.1 Various problems have been linked with the depletion in the workforce, including HIV (either because of death, sickness, or fear of exposure to the disease), the migration of trained staff, and the lack of resources and personal income.1 2 3 4

In some developing countries clinical officers were temporarily posted to alleviate the shortage of medical doctors.3 5 However, they have now become a more permanent strategy, being described as the “backbone” of healthcare in several settings.5 Clinical officers have a separate training programme to medical doctors, but their roles include many medical and surgical tasks usually carried out by doctors, such as anaesthesia, diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions, and prescribing. The perceived benefits of using clinical officers compared with doctors are reduced training and employment costs as well as enhanced retention within the local health systems.3 4 6

The scope of practice of a clinical officer within obstetrics is often determined by the country in which they work.2 In 19 out of 47 sub-Saharan African countries, clinical officers are authorised to provide obstetric care, yet in only five countries are they permitted to carry out caesarean sections and other emergency obstetric surgery.5 Given that caesarean section is the most common major surgical procedure in sub-Saharan Africa7 and must be delivered in a timely fashion to save a mother’s life,8 clinical officers could potentially play an important part in increasing accessibility and availability of emergency obstetric care, particularly caesarean section. However, uncertainty exists about their role,1 training, effectiveness, and safety. Given the central role that clinical officers increasingly have in the provision of obstetric care, we systematically reviewed and meta-analysed the effectiveness of clinical officers in caesarean section.

Methods

We searched databases for relevant literature on clinical officers within obstetrics in the developing world, with particular attention to maternal and perinatal mortality rates and adverse outcomes. We searched Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, BioMed Central, the Reproductive Health Library, and the Science Citation Index (from inception to August 2010). Hand searches complemented electronic searches, and we checked reference lists. Search terms were “clinical officer”, “medical officer”, “assistant medical officer”, “medex”, and “non physician clinicians”. No language restrictions were applied to the search.

We selected controlled studies that compared clinical officers and medically trained doctors for caesarean section in the developing world setting and that reported on any clinically relevant maternal or perinatal outcomes. The electronic searches were firstly scrutinised and full manuscripts of relevant studies were obtained. A final decision on inclusion or exclusion of manuscripts was made after two reviewers (AW and DL) had examined these manuscripts. Information was extracted from each selected article on study characteristics, quality, and outcome data. Descriptive studies were also examined to explore further the role of the clinical officer.

Methodological quality assessment

We assessed the selected studies for methodological quality using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.9 The controlled studies were evaluated for representativeness, selection, and comparability of the cohorts, ascertainment of the intervention and outcome, and the length and adequacy of follow-up. The risk of bias was regarded as low if a study obtained four stars for selection, two for comparability, and three for ascertainment of exposure.9 The risk of bias was considered to be medium in studies with two or three stars for selection, one for comparability, and two for exposure. Any study scoring one or zero stars for selection, comparability, or exposure was deemed to have a high risk of bias.

Data synthesis

We used the random effects model to pool the odds ratios from individual studies. Heterogeneity of treatment effects was evaluated using forest plots, χ2 and I2 tests; the terms low, moderate, and high heterogeneity were assigned to I2 values of over 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively. Where possible we present data for adjusted estimates on the forest plot to account for confounding factors. Analyses were done using Revman 5.0 statistical software.

Results

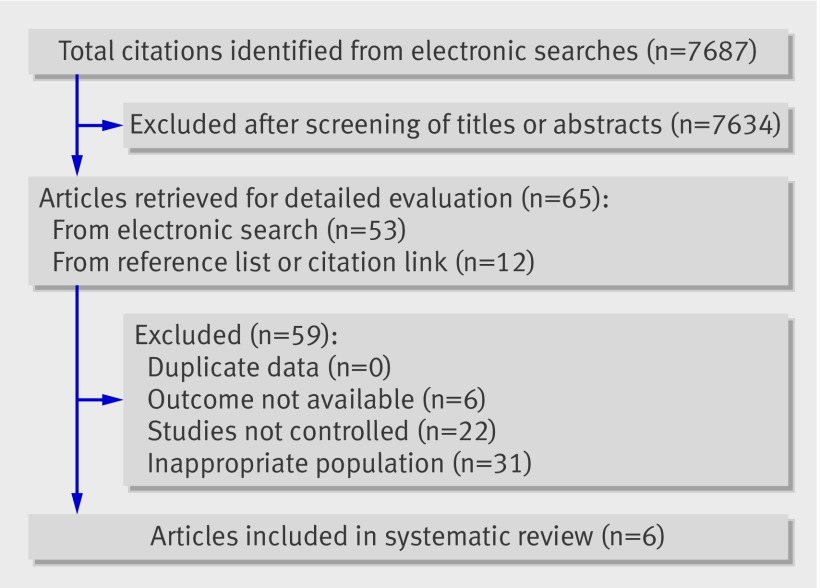

Six non-randomised controlled cohort studies (16 018 women) were included in the review (table 1[t1] and fig 1).1 3 8 10 11 12 When methodological quality was assessed on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, most studies had a medium risk for selection bias and medium to high risk for comparability and outcome assessment (table 2[t2]).

Fig 1 Study selection in review

Table 1.

Quality assessment of included studies using Newcastle-Ottawa scale

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Assessed outcome of interest was not present at start | Total | Risk of bias | Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | Total | Risk of bias | Assessment of outcome | Follow-up adequate for outcomes to occur | Adequate follow-up of cohorts | Total | Risk of bias | |||

| White 198711 | * | — | * | * | 3 | Medium | — | 0 | High | * | — | — | 1 | High | ||

| Pereira 19961 | * | — | * | * | 3 | Medium | — | 0 | High | * | — | — | 1 | High | ||

| Fenton 20038 | * | — | * | * | 3 | Medium | ** | 2 | Low | * | — | — | 1 | High | ||

| Chilopora 200710 | * | — | * | * | 3 | Medium | — | 0 | High | * | — | * | 2 | Medium | ||

| Hounton 20093 | * | — | * | * | 3 | Medium | * | 1 | Medium | * | — | — | 1 | High | ||

| McCord 200912 | * | — | * | * | 3 | Medium | — | 0 | High | * | — | — | 1 | High | ||

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in review

| Study, country | Details | Population | Characteristics of women | No (%) of caesarean sections | Indication for caesarean section | Surgeon allocation | Operation type | Potential confounders | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White 1987,11 Zaire | |||||||||

| Clinical officers | Nurses trained to carry out caesarean sections, laparotomies, and supracervical hysterectomies | Pregnant women needing caesarean section at two rural hospitals or health centres in northwest Zaire | Not given | 310 (88) | No separate details given on surgeon and indication for caesarean section; details only given for Karawa hospital (321 caesarean sections): cephalopelvic disproportion and obstructed labour 159 (50%), uterine inertia 70 (22%), previous caesarean section 54 (17%), fetal distress 22 (7%), placenta praevia 16 (4%) | One unit was without a doctor for one year; nurses carried out caesarean sections. In one unit doctors did not routinely do the most complicated operations, whereas in the other unit doctors operated on the most critical cases. Doctors carried out caesarean sections when no nurse was available, or when medical students were being trained | Not given | Delay in seeking care, delay in reaching care (transportation), other medical complications. No adjustments made | Maternal death |

| Doctors | Qualified doctor | Not given | 43 (12) | Not given | |||||

| Pereira 1996,1 Mozambique: | |||||||||

| Clinical officers | Assistant medical officers (clinical officers with surgical training) | Pregnant women needing caesarean sections at central hospital. Caesarean section rate was 16.5%. This was only hospital carrying out caesarean sections | Age 25.3 years, parity 2.2, resided in shanty town 353 (37%), antenatal care 948 (99%), twin pregnancy 25 (3%) | 958 (46) | Fetal distress 308 (32.2%), cephalopelvic disproportion 177 (18.5%), previous caesarean section 89 (9.3%), placental abruption or praevia 79 (8.2%), impending uterine rupture 72 (7.5%), eclampsia 31 (3.2%), pre-eclampsia 26 (2.7%), no information 176 (18.4%) | No random allocation for ethical reasons. Some selection may have occurred when patients were allotted to clinical officers or doctors | Caesarean section only 682 (71%), caesarean section plus subtotal hysterectomy 8 (1%), caesarean section plus total hysterectomy 3 (0.5%), caesarean section plus uterine repair 4 (0.5%), caesarean section plus tubal ligation 257 (26.5%), no information 4 (0.5%) | Age, parity, resided in shanty town, homeowner, antenatal care, twin pregnancy. No adjustments made | Maternal death, duration of postoperative stay, wound rupture or separation, condition of newborn |

| Doctors | Trained obstetricians and gynaecologists | Age 25.5 years, parity 2.2, resided in shanty town 404 (36%), antenatal care 1101 (99%), twin pregnancy 21 (2%) | 1113 (54) | Fetal distress 326 (29.3%), cephalopelvic disproportion 212 (19%), previous caesarean section 133 (11.9%), placental abruption or praevia 74 (6.6%), impending uterine rupture 68 (6.1%), eclampsia 40 (3.6%), pre-eclampsia 33 (3%), no information 227 (20.5%) | It was noted that emergencies prevented doctors attending complicated caesarean section. Furthermore, doctors carried out all elective caesarean sections (145, 7.0%) | Caesarean section only 832 (74.5%), caesarean section plus subtotal hysterectomy 10 (1%), caesarean section plus total hysterectomy 4 (0.5%), caesarean section plus uterine repair 5 (0.5%), caesarean section plus tubal ligation 256 (23%), no information 6 (0.5%) | |||

| Fenton 2003,8 Malawi: | |||||||||

| Clinical officers | Clinical officer surgeons | Women requiring caesarean section to deliver baby, dead or alive, after 28 weeks, including surgery for ruptured uterus. 23 district and two central hospitals | No separate details given on surgeons for characteristics: district hospital 5236 (65%), urban hospital 2834 (35%) | 5256 (65) | No separate details given on surgeon and indication for caesarean. Obstructed labour 5110 (63%), fetal distress 885 (11%), antepartum haemorrhage 384 (5%), pre-eclampsia 268 (3%), haemorrhagic shock 610 (8%), ruptured uterus 333 (4%), other 480 (6%) | Not given | Not given | Previous caesarean section, preoperative complications, fever, status and training of anaesthetist and surgeon, type of anaesthesia, blood loss, and need for blood transfusion. Adjusted for confounders | Maternal death, perinatal death |

| Doctors | Medically qualified doctors | 2814 (35) | Not given | ||||||

| Chilopora 2007,10 Malawi: | |||||||||

| Clinical officers | Licensed to practise independently and to carry out major emergency and elective surgery. Length of surgical experience: 44% >4 years, 24.3% 2-3 years, 21.4% <1 year, 9.3% 0 years, 0.6% no data | All women undergoing caesarean section during study period were included in 38 district hospitals; most were emergency caesarean sections | No major differences between groups operated on by clinical officers and doctors | 1875 (88) | No separate details given on surgeon and indication for caesarean section: cephalopelvic disproportion or obstructed labour 1230 (57.7%), previous caesarean section 452 (21.2%), fetal distress 264 (12.3%), impending uterine rupture 87 (4%), antepartum haemorrhage 77 (3.6%), cord prolapse 62 (2.9%), failure to progress, 60 (2.8%), breech in primigravida 53 (2.5%), eclampsia 49 (2.3%) | Not given | Caesarean section only 1569 (84%), caesarean section plus subtotal hysterectomy 11 (0.5%), caesarean section plus total hysterectomy 7 (0.5%), caesarean section plus uterine repair 59 (2.5%), caesarean section plus tubal ligation 224 (12%), not indicated 5 (0.5%) | Duration of surgeon’s practice, region of hospital, type of operation (if hysterectomy needed also). No adjustments made | Maternal death, infection, wound dehiscence, fever, perinatal death |

| Doctors | Trained doctors. Length of surgical experience: 59% >4 years, 19.9% 2-3 years, 17.2% <1 year, 3.9% no data | 256 (12) | Caesarean section only 185 (72%), caesarean section plus subtotal hysterectomy 8 (3%), caesarean section plus total hysterectomy 3 (2%), caesarean section plus uterine repair 7 (3%), caesarean section plus tubal ligation 53 (20%), not indicated 0 (0%) | ||||||

| Hounton 2009,3 Burkina Faso: | |||||||||

| Clinical officers | Clinical officers working in both rural and urban hospital | 2305 pregnant women needing caesarean section in 22 public sector urban and rural hospitals | Age 25 years, urban hospital 198 (27%), rural hospital 535 (73%) | 733 (32) | Obstructed labour 388 (53%), ruptured uterus 81 (11%), eclampsia 15 (2%), haemorrhage 44 (6%), other 205 (28%) | No details given on selection of operator; retrospective study. Doctors were, however, associated with more referred cases, although this was not statistically significant | Not given | Place of hospital, maternal age, reported clinical conditions; obstructive labour, ruptured uterus, eclampsia, haemorrhage, referral from other unit, type of anaesthesia. Adjustments made but adjusted statistics not given | Maternal death, perinatal death, haemorrhage, wound infection, wound dehiscence |

| Doctors | Trained doctors based at urban and rural hospitals | Age 25 years, urban hospital 877 (56%), rural hospital 143 (9%) | 1572 (68) | Obstructed labour 679 (43%), ruptured uterus 151 (9%), eclampsia 76 (5%), haemorrhage 84 (6%), other 581 (37%) | Not given | ||||

| McCord 2009,12 Tanzania: | |||||||||

| Clinical officers | Officially authorised assistant medical officers to provide clinical services, prescriptions, and minor surgery. Permitted to carry out obstetric care and caesarean section | 1088 pregnant women in 14 mission and government hospitals | Not given | 945 (87) | Absolute maternal indication (antepartum haemorrhage, postpartum haemorrhage, malpresentation, eclampsia, ectopic pregnancy, ruptured uterus, sepsis, and repair of vesicovaginal fistula) 312 (33.1%), major acute problem (no details given) 63 (6.6%), major chronic problem (severe anaemia, symptomatic AIDS, symptomatic malaria) 172 (18.2%), no information 398 (42.1%) | No reason given for choice of operator. Clinical officers were, however, more likely to carry out caesarean section with absolute maternal indicators or clear fetal indicator. Clinical officers had more difficulties than doctors in obtaining blood for transfusion | Not given | Condition on admission, type of operation, indication for operation, blood transfusions. No adjustments made | Maternal death, perinatal death |

| Doctors | Trained doctors | Medical school graduates with >1 year internship | Not given | 143 (13) | Absolute maternal indication (antepartum haemorrhage, postpartum haemorrhage, malpresentation, eclampsia, ectopic pregnancy, ruptured uterus, sepsis, and repair of vesicovaginal fistula) 48 (33.6%), major acute problem (no details given) 14 (9.8%), major chronic problem (severe anaemia, symptomatic AIDS, symptomatic malaria) 22 (15.3%), no information 59 (41.3%) | No reason given for choice of operator. Doctors were, however, less likely to carry out caesarean section for absolute maternal indicators or clear fetal indicator. Doctors had less difficulties than clinical officers in obtaining blood for transfusion | Not given |

Maternal mortality

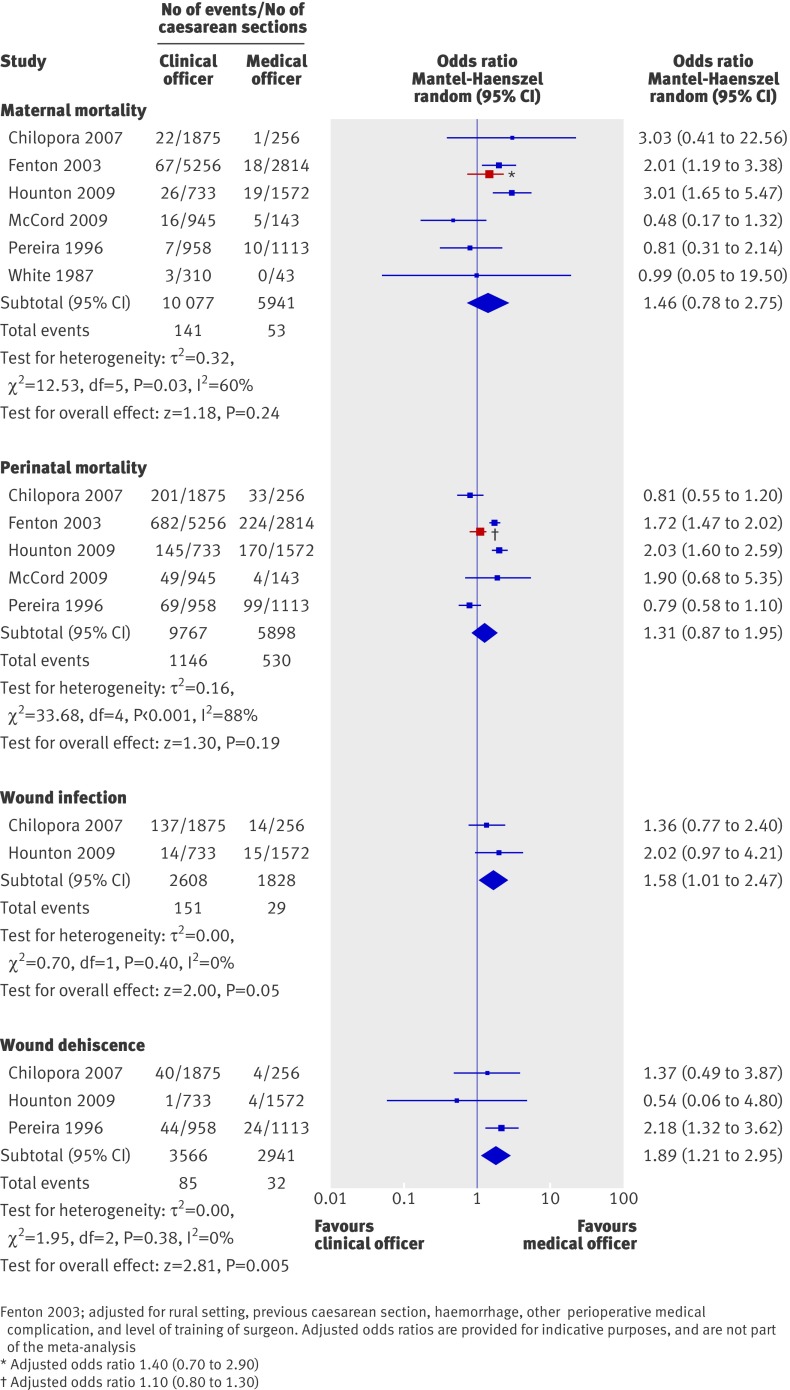

All six studies compared maternal mortality. The meta-analysis showed no statistically significant difference between the clinical officers and doctors (odds ratio 1.46, 95% confidence interval 0.78 to 2.75; P=0.24, fig 2). However, the analysis found significant heterogeneity (P=0.03), which was moderate (I2=60%). In one8 of the two studies3 8 that showed an increase in maternal mortality with clinical officers in the crude analysis, the increase was no longer statistically significant when the analysis was adjusted for rural setting, previous caesarean section, haemorrhage, other perioperative medical complications, and the level of training of the surgeon (adjusted odds ratio 1.4, 95% confidence interval 0.7 to 2.9). The second study3 that showed an increase in maternal mortality with the clinical officers also adjusted the analysis, but for reported diagnosis and referral status; the adjusted estimates were not, however, provided. The overall maternal mortality rate in the six studies was high, at 1.2%.

Fig 2 Clinical officers compared with doctors on outcomes of caesarean section

Perinatal mortality

Five studies1 3 8 10 12 (15 665 women) compared perinatal mortality. The meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the groups (odds ratio 1.31, 95% confidence interval 0.87 to 1.95; P=0.19, fig 2). The analysis found significant heterogeneity (P<0.01), which was high (I2=88%). In one8 of the two studies3 8 that showed an increase in perinatal mortality with clinical officers in the crude analysis, the increase was no longer statistically significant when adjusted for confounding factors (adjusted odds ratio 1.1, 95% confidence interval 0.8 to 1.3). The overall perinatal mortality rate in the five studies was high, at 10.7%.

Wound infection and wound dehiscence

Two studies3 10 (4436 women) compared the rates of wound infection. The meta-analysis found a significant increase in wound infection with clinical officers (odds ratio 1.58, 95% confidence interval 1.01 to 2.47; P=0.05, fig 2). Heterogeneity was not significant (P=0.40, I2=0%).

Three studies1 3 10 (6507 women) compared the rates of wound dehiscence. The meta-analysis showed a significant increase in wound dehiscence when clinical officers carried out caesarean sections compared with doctors (odds ratio 1.89, 95% confidence interval 1.21 to 2.95; P=0.005, fig 2). Evidence of significant heterogeneity was lacking (P=0.38, I2=0%).

Training of clinical officers

All six papers gave training details of clinical officers; training length and specification varied between countries. In Zaire11 and Burkina Faso,3 nurses attend a two year training course to become clinical officers, with an additional 1-2 years of surgical training in Zaire. In Malawi8 10 and Mozambique,1 clinical officers require a three year health foundation course, with a year as an intern at a hospital or in surgical training. In Tanzania,12 clinical officers undergo three years’ medical training, with a further two years in clinical training plus three months in surgery and three months in obstetrics. In Burkina Faso,3 clinical officers are required to undergo a six month curriculum in emergency surgery to carry out operative obstetric care.

Discussion

The meta-analysis did not show a statistically significant difference in maternal or perinatal mortality in caesarean sections carried out by clinical officers compared with doctors. However, when the outcomes of wound dehiscence and wound infection were assessed, both were significantly more frequent in caesarean sections carried out by clinical officers.

Strengths and limitations of the review

All of the six studies examined were comparative cohort studies. As they were not randomised trials, there is the potential for bias. When methodological quality was assessed on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale there was a medium risk of selection bias and a medium to high risk of bias in comparability and outcome assessment for most studies. For example, in one study,1 elective caesarean sections were exclusively carried out by doctors, whereas emergencies were carried out by both doctors and clinical officers. As elective caesarean section is associated with better outcomes than emergency caesarean section,13 this arrangement would have conferred an advantage to doctors. Furthermore, clinical officers tend to be located in rural areas,3 where access to lifesaving facilities such as blood transfusion and high dependency care may not be available. Another study8 tackled such issues by adjusting for rural setting, previous caesarean section, haemorrhage, other perioperative medical complications, and the level of training of the surgeon. Their initial analysis showed an excess in maternal and perinatal mortality associated with clinical officers. However, when adjustments were made for the relevant factors, the difference in these outcomes was no longer statistically significant. This suggests the possibility of more high risk cases in the clinical officer group in this study. It is also plausible that the bias could be in the other direction. For instance, the perceived severity of the situation may have resulted in a doctor rather than a clinical officer carrying out the caesarean section. This may cause bias in favour of clinical officers. Although most studies reported no differences in patient characteristics1 3 8 10 or indication for caesarean section,1 3 8 10 11 12 and some studies adjusted for various factors,3 8 residual confounding can still exist.

Maternal and perinatal outcomes were statistically significantly heterogeneous, which may reflect the diversity of the setting and the population, indications for surgery, surgical approach and training, and role of the clinical officers in these studies. Given such clinical heterogeneity, it is unsurprising that statistical heterogeneity was identified in the analyses. Formal exploration of the reasons for statistical heterogeneity by study features was limited owing to the small number of studies identified in our review. However, when confounding factors were adjusted for, the observed heterogeneity decreased.

Study implications

Although we acknowledge caution when interpreting the findings of this meta-analysis owing to the non-randomised nature of the included studies, the present study remains the best current evidence on these outcomes.

Clinical officers were associated with an increase in wound infection and dehiscence. This was consistent in the two studies that examined these outcomes. We speculate that these outcomes may be associated with surgical technique and a need for enhanced training. One study1 highlighted that 97% of caesarean sections were through a vertical abdominal incision, which is known to be associated with increased wound dehiscence and other adverse outcomes when compared with horizontal incisions.14 Thus there may be substantial scope for improvement in surgical technique. Evidence shows that specialist training of clinical officers can improve outcomes. One study8 measured the incidence of maternal death from anaesthesia, when administered by clinical officers who had or had not received formal training. The maternal mortality rate was much higher in those who had not received training compared with those who had (2.4% v 0.9%).

Our review assesses the important and specific role of clinical officers in carrying out caesarean section, which is an immediate determinant of outcome. However, this must be placed within the wider context of the many distant and intermediate determinants of maternal health and mortality15 (see web extra on bmj.com). Although little work has been done to assess the role of clinical officers in tackling these wider determinants, they can have an important impact on these factors through, for example, increasing access to services5 16 and a role in family planning2and broader preventive health programmes5 17 to reduce maternal mortality. Furthermore, part of the value of the clinical officer role is that their job can be adapted to suit local needs and conditions. Yet as there are no internationally agreed curriculums or scope of practice guidelines,2 the importance of evaluating clinical officers in their specific setting needs to be recognised.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis suggests that the provision of caesarean section by clinical officers does not result in a significant increase in maternal or perinatal mortality. Enhanced access to emergency obstetric surgery through greater deployment of clinical officers, in countries with poor coverage by doctors, can form part of the solution to meet Millennium Development Goals 4 (reducing child mortality) and 5 (improving maternal health).

What is already known on this topic

When compared with doctors, clinical officers cost less to train and employ, and are retained better within health systems in developing countries

Clinical officers are the backbone of obstetric care in many developing countries, performing as much as 4/5th of caesarean sections in some countries

There is uncertainty about the effectiveness and safety of clinical officers performing caesarean section surgery

What this study adds

Meta-analysis of six controlled studies found no differences between the clinical officers and doctors for maternal and perinatal death after caesarean section

Wound dehiscence and wound infection were found to be significantly more frequent in caesarean sections performed by clinical officers

We thank Paul Fenton for constructive feedback on the manuscript.

Contributors: AW and AC conceived the review. AW and DL carried out the search, study selection, and data extraction. AW, ST, and AC analysed the results. AW, AC, and DL drafted the manuscript. CM and KSK provided critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. AC is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the registered charity Ammalife (www.ammalife.org) and Birmingham Women’s NHS foundation Trust R&D department.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that no support from any institution for the submitted work; no relationships with any institution that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d2600

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Determinants of maternal mortality

References

- 1.Pereira C, Bugalho A, Bergstrom S, Vaz F, Cotiro M. A comparative study of caesarean deliveries by assistant medical officers and obstetricians in Mozambique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:508-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dovlo D. Using mid-level cadres as substitutes for internationally mobile health professionals in Africa. A desk review. Hum Resour Health 2004;2:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hounton SH, Newlands D, Meda N, De Brouwere V. A cost-effectiveness study of caesarean-section deliveries by clinical officers, general practitioners and obstetricians in Burkina Faso. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley S, McAuliffe E. Mid-level providers in emergency obstetric and newborn health care: factors affecting their performance and retention within the Malawian health system. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullan F, Frehywot S. Non-physician clinicians in 47 sub-Saharan African countries. Lancet 2007;370:2158-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Record R, Mohiddin A. An economic perspective on Malawi’s medical “brain drain.” Global Health 2006;2:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenton P. The epidemiology of district surgery in Malawi. East Central African J Surg 1997;3:33-41. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenton PM, Whitty CJ, Reynolds F. Caesarean section in Malawi: prospective study of early maternal and perinatal mortality. BMJ 2003;327:587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells G. The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analysis. Proceedings of the Third Symposium on Systematic Reviews. Beyond the basics: improving quality and impact; 2000 Jul 3-5. Oxford, 2000.

- 10.Chilopora G, Pereira C, Kamwendo F, Chimbiri A, Malunga E, Bergstrom S. Postoperative outcome of caesarean sections and other major emergency obstetric surgery by clinical officers and medical officers in Malawi. Hum Resour Health 2007;5:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White SM, Thorpe RG, Maine D. Emergency obstetric surgery performed by nurses in Zaire. Lancet 1987;2:612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCord C, Mbaruku G, Pereira C, Nzabuhakwa C, Bergstrom S. The quality of emergency obstetrical surgery by assistant medical officers in Tanzanian district hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w876-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis G. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer—2003-2005. The seventh report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. CEMACH, 2007.

- 14.Brown SR, Goodfellow PB. Transverse versus midline incisions for abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;4:CD005199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy J, Maine D. A framework for analyzing the determinants of maternal mortality. Stud Fam Plann 1992;23:23-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaz F, Bergstrom S, Vaz ML, Langa J, Bugalho A. Training medical assistants for surgery. Bull World Health Organ 1999;77:688-91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task-shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Hum Resour Health 2010;8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Determinants of maternal mortality