Abstract

The Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach is applicable in all clinical emergencies for immediate assessment and treatment. The approach is widely accepted by experts in emergency medicine and likely improves outcomes by helping health care professionals focusing on the most life-threatening clinical problems. In an acute setting, high-quality ABCDE skills among all treating team members can save valuable time and improve team performance. Dissemination of knowledge and skills related to the ABCDE approach are therefore needed. This paper offers a practical “how-to” description of the ABCDE approach.

Keywords: emergency medicine, general medicine, internal medicine, multiple trauma, multiple injury

Introduction

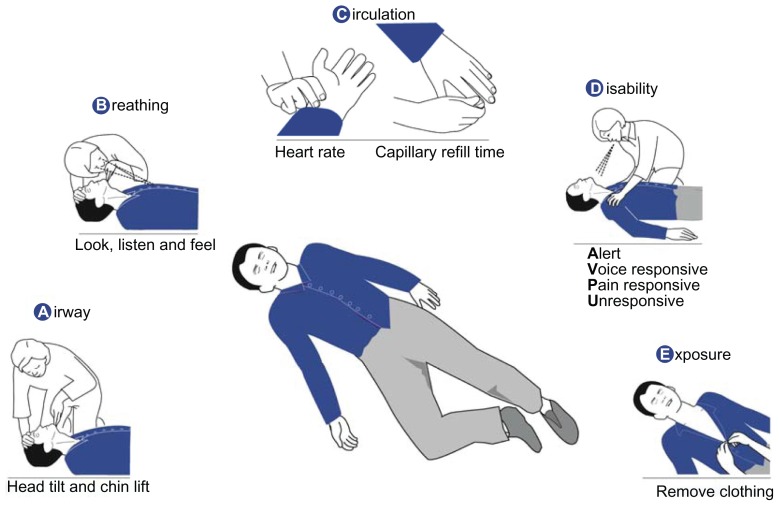

The Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach is a systematic approach to the immediate assessment and treatment of critically ill or injured patients. The approach is applicable in all clinical emergencies. It can be used in the street without any equipment (Figure 1) or, in a more advanced form, upon arrival of emergency medical services, in emergency rooms, in general wards of hospitals, or in intensive care units.1 The aim of this paper is to offer a practical “how-to” description of the ABCDE approach.

Figure 1.

The ABCDE approach without the use of equipment.

The aims of the ABCDE approach are:

to provide life-saving treatment

to break down complex clinical situations into more manageable parts

to serve as an assessment and treatment algorithm

to establish common situational awareness among all treatment providers

to buy time to establish a final diagnosis and treatment.

Evidence supporting the ABCDE approach

The evidence supporting the systematic ABCDE approach to critically ill or injured patients is expert consensus. The approach is widely accepted and used by emergency technicians, critical care specialists, and traumatologists. In analogy, algorithms for resuscitation are applied to improve the speed and quality of treatment. The authors believe that a generally accepted algorithm for the ABCDE approach taught to health care professionals may improve treatment of the critically ill and injured, whereas differences in the interpretation of the algorithm may lead to confusion.2 A uniform adoption of the ABCDE approach among members of a treatment team is likely to improve team performance.

Training health care professionals for recognition and management of critically ill patients increases confidence and reduces concerns about being responsible for the severely ill.3 Resuscitation algorithm training and the use of algorithms in treatment of septic patients impact outcome.4,5

Which patients need ABCDE?

The ABCDE approach is applicable for all patients, both adults and children. The clinical signs of critical conditions are similar regardless of the underlying cause. This makes exact knowledge of the underlying cause unnecessary when performing the initial assessment and treatment. The ABCDE approach should be used whenever critical illness or injury is suspected. It is a valuable tool for identifying or ruling out critical conditions in daily practice. Cardiac arrest is often preceded by adverse clinical signs and these can be recognized and treated with the ABCDE approach to potentially prevent cardiac arrest.6–8 The ABCDE approach is also recommended as the first step in postresuscitation care upon the return of spontaneous circulation.9

The ABCDE approach is not recommended in cardiac arrest. When confronted with a collapsed patient, first ensure the safety of yourself, bystanders, and the victim. Then check for cardiac arrest (unresponsive, abnormal or absent breathing, and, if trained, pulse-check lack of carotid artery pulse). If the victim is in cardiac arrest, call for help and start cardiopulmonary resuscitation according to guidelines.9 If the patient is not in cardiac arrest, use the ABCDE approach.

Which physicians need ABCDE?

All health care professionals can encounter critically ill or injured persons, either at work or in private life, and may therefore benefit from knowing the ABCDE approach. The lay public expects health care professionals to act when confronted with illness or injury, whether it occurs in the street with no equipment at hand or in the hospital. These expectations can be met by instituting life-saving treatment using the ABCDE approach. Assessment and treatment can be initiated without equipment and more advanced interventions can be applied on arrival of emergency medical services, in a clinic, or at the hospital.

Medical emergencies, including pediatric emergencies, occur in the general practitioners office more often than expected.10–14 Patients turn to their general practitioner even when it would be more appropriate to call emergency medical services for immediate hospital admission. Unfortunately, the general practitioner’s office is not always sufficiently prepared.10–15

ABCDE principles

With the ABCDE approach, the initial assessment and treatment are performed simultaneously and continuously. Even when a critical condition is evident, the cause may be elusive; in such situations, life-saving treatment must be instituted before a definitive diagnosis has been obtained. Early recognition and effective initial treatment prevents deterioration and buys time for a definitive diagnosis to be made. Causally focused treatment can then be instituted.

The mnemonic “ABCDE” stands for Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, and Exposure. First, life-threatening airway problems are assessed and treated; second, life-threatening breathing problems are assessed and treated; and so on. Using this structured approach, the aim is to quickly identify life-threatening problems and institute treatment to correct them.

Often, assistance will be required from emergency medical services, a specialist, or a hospital response team (eg, medical emergency team or cardiac arrest team). The ABCDE approach helps to rapidly recognize the need for assistance. Responders should call for help as soon as possible and exploit the resources of all persons present to increase the speed of both assessment and treatment. Improved outcome is most often based on a team effort.

On completion of the initial ABCDE assessment, assessments should be repeated until the patient is stable. It must be remembered that it may take a few minutes before the effect of an intervention is evident. In case of deterioration, reassessment should be performed.

Table 1 gives important summary points of the ABCDE approach.

Table 1.

Summary points of the ABCDE approach

|

The ABCDE approach

First, one’s own safety must be ensured. Then, a general impression is obtained by simply looking at the patient (skin color, sweating, surroundings, and so on). Although this is valuable, the critical clinical situation is frequently complex and the systematic approach described below helps break it down into manageable parts (Table 2).

Table 2.

The ABCDE approach with important assessment points and examples of treatment options

| Assessment | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| A – Airways | Voice Breath sounds |

Head tilt and chin lift Oxygen (15 l min−1) Suction |

| B – Breathing | Respiratory rate (12–20 min−1) Chest wall movements Chest percussion Lung auscultation Pulse oximetry (97%–100%) |

Seat comfortably Rescue breaths Inhaled medications Bag-mask ventilation Decompress tension pneumothorax |

| C – Circulation | Skin color, sweating Capillary refill time (<2 s) Palpate pulse rate (60–100 min−1) Heart auscultation Blood pressure (systolic 100–140 mmHg) Electrocardiography monitoring |

Stop bleeding Elevate legs Intravenous access Infuse saline |

| D – Disability | Level of consciousness – AVPU

Pupillary light reflexes Blood glucose |

Treat Airway, Breathing, and Circulation problems Recovery position Glucose for hypoglycemia |

| E – Exposure | Expose skin Temperature |

Treat suspected cause |

Notes: Normal adult ranges are given in parentheses. Importantly, a patient with values within the given ranges may still be critically ill. Assessment and treatment points in italics require equipment. The approach described in this table is primarily aimed at the nonspecialist and is not exhaustive.

A – Airway: is the airway patent?

If the patient responds in a normal voice, then the airway is patent. Airway obstruction can be partial or complete. Signs of a partially obstructed airway include a changed voice, noisy breathing (eg, stridor), and an increased breathing effort. With a completely obstructed airway, there is no respiration despite great effort (ie, paradox respiration, or “see-saw” sign). A reduced level of consciousness is a common cause of airway obstruction, partial or complete. A common sign of partial airway obstruction in the unconscious state is snoring.

Untreated airway obstruction can rapidly lead to cardiac arrest. All health care professionals, regardless of the setting, can assess the airway as described and use a head-tilt and chin-lift maneuver to open the airway (Figure 2). With the proper equipment, suction of the airways to remove obstructions, for example, blood or vomit, is recommended. If possible, foreign bodies causing airway obstruction should be removed. In the event of a complete airway obstruction, treatment should be given according to current guidelines.9 In brief, to conscious patients give five back blows alternating with five abdominal thrusts until the obstruction is relieved. If the victim becomes unconscious, call for help and start cardiopulmonary resuscitation according to guidelines.9

Figure 2.

Head-tilt and chin-lift to open the airway.

Importantly, high-flow oxygen should be provided to all critically ill persons as soon as possible.

B – Breathing: is the breathing sufficient?

In all settings, it is possible to determine the respiratory rate, inspect movements of the thoracic wall for symmetry and use of auxiliary respiratory muscles, and percuss the chest for unilateral dullness or resonance. Cyanosis, distended neck veins, and lateralization of the trachea can be identified. If a stethoscope is available, lung auscultation should be performed and, if possible, a pulse oximeter should be applied.

Tension pneumothorax must be relieved immediately by inserting a cannula where the second intercostal space crosses the midclavicular line (needle thoracocentesis). Bronchospasm should be treated with inhalations.

If breathing is insufficient, assisted ventilation must be performed by giving rescue breaths with or without a barrier device. Trained personnel should use a bag mask if available.

C – Circulation: is the circulation sufficient?

The capillary refill time and pulse rate can be assessed in any setting. Inspection of the skin gives clues to circulatory problems. Color changes, sweating, and a decreased level of consciousness are signs of decreased perfusion. If a stethoscope is available, heart auscultation should be performed. Electrocardiography monitoring and blood pressure measurements should also be performed as soon as possible. Hypotension is an important adverse clinical sign. The effects of hypovolemia can be alleviated by placing the patient in the supine position and elevating the patient’s legs. An intravenous access should be obtained as soon as possible and saline should be infused.

D – Disability: what is the level of consciousness?

The level of consciousness can be rapidly assessed using the AVPU method, where the patient is graded as alert (A), voice responsive (V), pain responsive (P), or unresponsive (U). Alternatively, the Glasgow Coma Score can be used.16 Limb movements should be inspected to evaluate potential signs of lateralization. The best immediate treatment for patients with a primary cerebral condition is stabilization of the airway, breathing, and circulation. In particular, when the patient is only pain responsive or unresponsive, airway patency must be ensured, by placing the patient in the recovery position, and summoning personnel qualified to secure the airway. Ultimately, intubation may be required. Pupillary light reflexes should be evaluated and blood glucose measured. A decreased level of consciousness due to low blood glucose can be corrected quickly with oral or infused glucose.

E – Exposure: any clues to explain the patient’s condition?

Signs of trauma, bleeding, skin reactions (rashes), needle marks, etc, must be observed. Bearing the dignity of the patient in mind, clothing should be removed to allow a thorough physical examination to be performed. Body temperature can be estimated by feeling the skin or using a thermometer when available.

History of the ABCDE approach

The formulation of the mnemonic ABC has its roots in the 1950s. Safar described methods to safe-guard the airway and deliver rescue breaths, thereby giving rise to the first two letters of the mnemonic, A and B.17 Kouwenhoven and colleagues described closed-chest cardiac massage, adding the letter C.18 Dr Safar first described the techniques in combination.19

The further development and dissemination of the ABCDE approach has been attributed to Styner. In 1976, Styner crashed in a small aircraft with his family, and they were admitted to the local hospital. Here, he observed an inadequacy of the emergency care provided. Emphasizing the systematic approach to the critically injured patient, he formed the basis of the Advanced Trauma Life Support courses. Accordingly, the ABCDE approach is an extension of the initially described ABC approach for patients in cardiac arrest to patients experiencing all medical and surgical emergencies.

Conclusion

The ABCDE approach is a strong clinical tool for the initial assessment and treatment of patients in acute medical and surgical emergencies, including both prehospital first-aid and in-hospital treatment. It aids in determining the seriousness of a condition and to prioritize initial clinical interventions. Widespread knowledge of and skills in the ABCDE approach are likely to enhance team efforts and thereby improve patient outcome.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Gitte Skovgård Jensen for expert assistance in preparation of the figures.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Thim T, Krarup NH, Grove EL, Lofgren B. ABCDE – a systematic approach to critically ill patients. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172(47):3264–3266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guly HR. ABCDEs. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(4):358. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Featherstone P, Smith GB, Linnell M, Easton S, Osgood VM. Impact of a one-day inter-professional course (ALERT) on attitudes and confidence in managing critically ill adult patients. Resuscitation. 2005;65(3):329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moretti MA, Cesar LA, Nusbacher A, Kern KB, Timerman S, Ramires JA. Advanced cardiac life support training improves long-term survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2007;72(3):458–465. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan JP, Soar J, Zideman DA, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 1. Executive summary. Resuscitation. 2010;81(10):1219–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Soar J, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2010;81(10):1305–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soar J, Perkins GD, Abbas G, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 8. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances: Electrolyte abnormalities, poisoning, drowning, accidental hypothermia, hyperthermia, asthma, anaphylaxis, cardiac surgery, trauma, pregnancy, electrocution. Resuscitation. 2010;81(10):1400–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koster RW, Baubin MA, Bossaert LL, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 2. Adult basic life support and use of automated external defibrillators. Resuscitation. 2010;81(10):1277–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mansfield CJ, Price J, Frush KS, Dallara J. Pediatric emergencies in the office: are family physicians as prepared as pediatricians? J Fam Pract. 2001;50(9):757–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sempowski IP, Brison RJ. Dealing with office emergencies. Stepwise approach for family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:1464–1472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheeler DS, Kiefer ML, Poss WB. Pediatric emergency preparedness in the office. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(11):3333–3342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toback SL. Medical emergency preparedness in office practice. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(11):1679–1684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dick ML, Schluter P, Johnston C, Coulthard M. GPs’ perceived competence and comfort in managing medical emergencies in southeast Queensland. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31(9):870–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs S, Jaffe DM, Christoffel KK. Pediatric emergencies in office practices: prevalence and office preparedness. Pediatrics. 1989;83(6):931–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lockey A, Balance J, Domanovits H, et al., editors. Advanced Life Support ERC Guidelines 2010 Edition. Belgium: European Resuscitation Council; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Safar P, McMahon M. Mouth-to-airway emergency artificial respiration. J Am Med Assoc. 1958;166(12):1459–1460. doi: 10.1001/jama.1958.02990120051010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kouwenhoven WB, Jude JR, Knickerbocker GG. Closed-chest cardiac massage. JAMA. 1960;173:1064–1067. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020280004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safar P, Brown TC, Holtey WJ, Wilder RJ. Ventilation and circulation with closed-chest cardiac massage in man. JAMA. 1961;176:574–576. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040200010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]