Abstract

We previously demonstrated that dengue virus (DENV) nonstructural 4B protein (NS4B) induced dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF)-associated immunomediators in THP-1 monocytes. Moreover, cleavage of NS4AB polyprotein by the NS2B3 protease, significantly increased immunomediator production to levels found after DENV infection. In this report using primary human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) transwell permeability model and HMVEC monolayer, we demonstrate that the immunomediators secreted in the supernatants of DENV-infected monocytes increase HMVEC permeability and expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin. Moreover, maturation of NS4B via cleavage of 2KNS4B is sufficient to induce immunomediators that cause HMVEC phenotypic changes, which appear to be synergistically induced by TNFα and IL-8. These data suggest that therapies targeting the maturation steps of NS4B, particularly 2KNS4B processing, may reduce overall DHF-associated immunomediator levels, thereby reducing DHF-associated morbidity and mortality. Alternatively, TNFα inhibitors may be a valid intervention strategy during the later stages of infection to prevent DHF progression.

Keywords: Dengue virus, DENV, Flavivirus, chemokines and cytokines, nonstructural 2KNS4B protein, THP-1 monocytes, human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC), adhesion molecules, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin, transwell permeability model, TEER, FITC-dextran

Introduction

Dengue virus (DENV) causes substantial human morbidity and mortality worldwide infecting an estimated 50-100 million people annually and causing over 500,000 hospitalizations (World Health Organization, 2009). Approximately 10% of patients presenting with classic dengue fever (DF) progress to severe dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS), which may lead to death (Malavige et al., 2004; WHO, 1997). DHF/DSS mortality rates average 5%, with approximately 25,000 deaths each year (World Health Organization, 1997). Although mechanisms leading to DHF/DSS are unclear, an indisputable characteristic of severe dengue disease is plasma leakage resulting from vascular endothelial cell activation, as measured by adhesion molecules expression and increased vascular cell permeability (Chang, Harn, and Nimmannitya, 1990; Khongphatthanayothin et al., 2006; Koraka et al., 2004; Srichaikul and Nimmannitya, 2000; Srikiatkhachorn, 2009). Clinical evidence suggests that plasma leakage progresses rapidly after peak viremia and defervescence when elevated levels of chemokines and cytokines exist in the periphery (Braga et al., 2001; Libraty et al., 2002; Murgue; Raghupathy et al., 1998; Vaughan et al., 2008; Vitarana et al., 1991).

There is little evidence that DENV infects vascular endothelial cells in patients progressing to DHF/DSS (Halstead, 1989). DENV antigens have been demonstrated in lung endothelial cells collected at post-mortem (Jessie, 2004) and DENV replicates efficiently in human endothelial cells in-vitro (Anderson et al., 1997; Andrews et al., 1978; Arevalo et al., 2009; Avirutnan et al., 1998; Bonner and O’Sullivan, 1998; Bunyaratvej et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2000; Warke et al., 2003). However, the significance of DENV-infected endothelial cells during DHF pathogenesis remains inconclusive due to the scarcity of human autopsy studies and the timing of specimen collection. Moreover, endothelial cells treated in-vitro with the supernatants from DENV-infected monocytes or monocyte-derived macrophages increase expression of adhesion molecules and permeability, respectively, while direct infection of endothelial cells does not alter either phenotype (Anderson et al., 1997; Bonner and O’Sullivan, 1998; Carr et al., 2003; Chareonsirisuthigul, Kalayanarooj, and Ubol, 2007), suggesting that the elevated immunomediators in DHF/DSS patients are primarily responsible for modulating endothelial cell adhesion molecules and thereby cell permeability.

Other reports suggest that DENV preferentially infects peripheral blood monocytes which contribute to the overproduction of immunomediators detected during severe dengue disease (Durbin et al., 2008). Additionally, DENV-infected primary human monocytes secrete high levels of DHF/DSS-associated immunomediators (Chareonsirisuthigul, Kalayanarooj, and Ubol, 2007; Ubol et al., 2008). We previously reported that DENV nonstructural 5 protein (NS5), NS4B or maturation of NS4B via cleavage of 2KNS4B increased the secretion of IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, and IP-10 in THP-1 monocytic cell line (Kelley et al., 2011). Similarly, other investigators have demonstrated that IL-6, IL-8 or TNFα is primarily responsible for initiating and sustaining increased vascular endothelial cell permeability (Carr et al., 2003; Petreaca et al., 2007; Raghupathy et al., 1998) whereas TNFα and IL-1β are the primary stimulatory molecules for intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and E-selectin (E-sel) (Anderson et al., 1997; Cardier et al., 2005; Detmar et al., 1992; Wyble et al., 1996). Currently, animal models are inadequate to study DENV immunopathogenesis and in-vitro studies examining adhesion molecule expression and permeability vary due to their inconsistent use of macro- and micro-vascular endothelial cells.

In this report, we demonstrate that TNFα and IL-8 are the primary vasoactive mediators produced from DENV-infected THP-1 monocytic cells. Importantly, cleavage of 2KNS4B during NS4B maturation is sufficient to induce TNFα and IL-8, which may synergistically induce phenotypic changes in primary human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC). We also demonstrate that membrane permeability changes directly correlate with increased expression of VCAM-1 and E-sel. Overall, these data provide a partial explanation for the source of DENV-induced, monocyte-derived vasoactive mediators. Moreover, the increased HMVEC permeability and expression of adhesion molecules are primarily via an indirect route, requiring the participation of virus-infected monocytes, specifically expression of 2KNS4B, rather than virus-infected endothelial cells.

Results

Immunomediators secreted in the supernatants of DENV-infected THP-1 monocytes increase HMVEC adhesion molecules and permeability

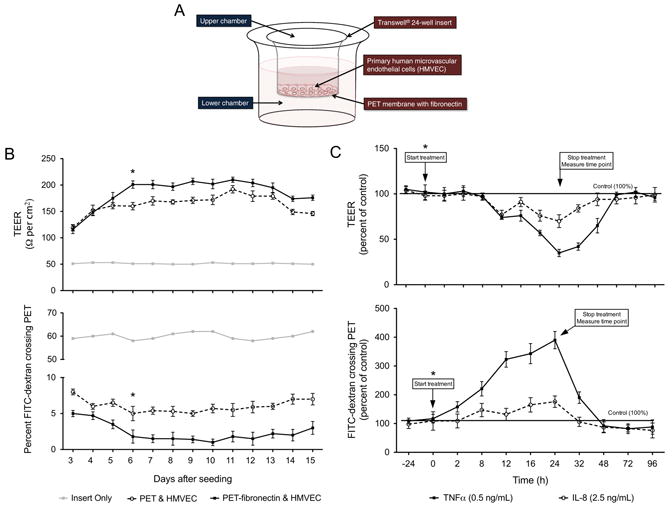

We previously demonstrated that DENV-infected THP-1 cells significantly increased the secretion of IP-10, TNFα, IL-6 and IL-8 (Supplemental Table 1) (Kelley et al., 2011). Before determining whether the immunomediators secreted in the aforementioned supernatants could increase HMVEC adhesion molecules or permeability, we optimized the in-vitro HMVEC transwell permeability model. The HMVEC model was constructed with Transwell® 24-well inserts consisting of a PET/fibronectin membrane layered with primary HMVEC (Fig. 1A). To measure permeability, we implemented both trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) and FITC-dextran permeability assays as previously described by us and other investigators (Bonner and O’Sullivan, 1998; Carr et al., 2003; Dewi, Takasaki, and Kurane, 2008; Petreaca et al., 2007; Verma et al., 2009). We observed that HMVEC seeded on PET membranes pretreated with fibronectin provided more effective membrane integrity than the PET membranes without fibronectin and the ideal treatment window for our experiments was between days 6 and 10 after HMVEC seeding (Fig. 1B). An increased TEER reading of approximately 200 Ω/cm2 corresponded with a decreased FITC-dextran reading of approximately 2 percent crossing for each time point from days 6 to 10 (Fig. 1B), indicating sustained HMVEC integrity. Given that TNFα and IL-8 increase permeability (Dewi, Takasaki, and Kurane, 2004; Jacobs and Levin, 2002; Petreaca et al., 2007; Talavera et al., 2004) and to determine optimal control and incubation times, we tested both mediators as positive controls. We observed that TNFα (0.05 ng/mL) and IL-8 (2.5 ng/mL) consistently increased cell permeability. Maximum permeability occurred at 24 h after treatment wherein TNFα and IL-8 altered TEER to approximately 50% and 25% of controls, respectively (Fig. 1C). The same concentrations of TNFα and IL-8 increased FITC-dextran crossing the membrane to almost 400% and 150% of controls, respectively. As expected, after removal of TNFα and IL-8 and washing with buffer, a full recovery of membrane integrity was observed after an additional 24 h of incubation with only culture media (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Optimization of the in-vitro HMVEC permeability model. (A) Transwell® 24-well inserts with PET membranes either with or without fibronectin coating were used for seeding 100,000 HMVEC cells and incubated with 250 μL and 2 mL of media in the upper and lower chambers, respectively. (B) To determine the optimal treatment window, TEER, presented as Ω/cm2, and the percent FITC-dextran crossing the HMVEC/PET membranes were measured every day for 15 days after seeding cells. The maximum membrane tightness was observed on day 6 after seeding when the TEER was above 200 Ω/cm2 and less than 4% of FITC-dextran crossed the membrane. Therefore, (*) represents the time point, day 6 after seeding, chosen to start treatment of the HMVEC permeability model. (C) To determine the optimal incubation period and end point time to measure permeability, either 250 μL of 0.5 ng/mL TNFα (125 pg total) or 2.5 ng/mL of IL-8 (625 pg total) was incubated with the PET-fibronectin/HMVEC membrane beginning on day 6 after seeding and TEER and FITC-dextran assay was conducted every day. Data are presented as percent of non-treated control membranes. The optimal time point to measure permeability was found to be 24 h after treatment. Bars represent the mean ± SD of two independent experiments conducted in triplicate.

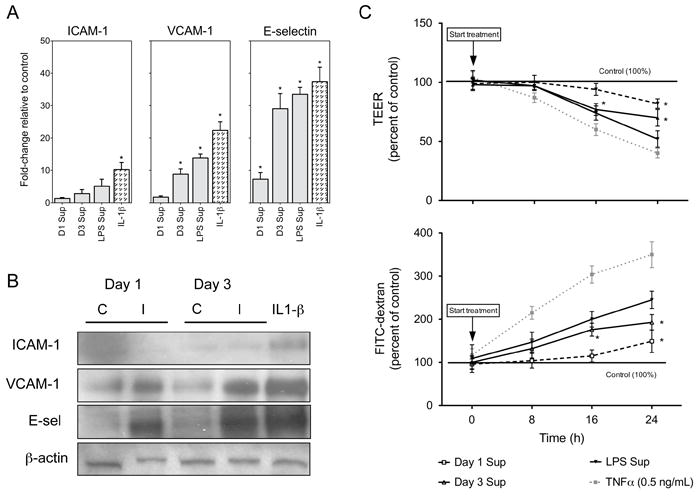

To better understand the kinetics of DENV-induced HMVEC phenotypic changes, we initially tested the supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cells for increases in ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel expression and permeability. The supernatants were UV-treated to inactivate infectious virus (Verma et al., 2009) and incubated with HMVEC monolayers for 16 h as previously described (Anderson et al., 1997). We demonstrated using qRT-PCR that VCAM-1 and E-sel mRNA transcript levels increased 10- and 30-fold, respectively, but ICAM-1 mRNA did not significantly increase at 16 h (Fig. 2A). Also, we demonstrated by western blot that supernatants collected at days 1 and 3 after infection induced VCAM-1 and E-sel compared to the supernatants from mock-infected THP-1 control cells, similar to mRNA expression patterns (Fig. 2B). The observed level of ICAM-1 protein expression remained unchanged at 16 h after treatment (Fig. 2B). Given that other investigators have demonstrated ICAM-1 expression on HMVEC cells (Detmar et al., 1992), we conducted a time point experiment, incubating HMVEC with 200 pg of IL-1β, based on detected serum levels in DHF patients, as previously described (Bozza et al., 2008; Kuno and Bailey, 1994; Molet et al., 1998). We observed by western blot that expression of ICAM-1 peaked at 8 h after incubation with IL-1β (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Indeed, when we incubated HMVEC with the supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cells for 8 h, we observed an increase in the expression of ICAM-1 (Supplemental Fig. 1B). We then demonstrated that supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cell collected at day 1 after infection significantly increased HMVEC permeability at 24 h after incubation whereas day 3 supernatants initiated permeability more rapidly and to higher levels, significantly increasing at 16 and 24 h after incubation as measured by TEER and FITC-dextran crossing the PET/HMVEC membrane (Fig. 2C). Moreover, we demonstrated no significant differences in HMVEC viability for up to 2 days after treatment with TNFα, IL-8, supernatants from THP-1 cells incubated with LPS or direct infection with DENV (Supplemental Fig. 2). Taken together, these data suggest that the immunomediators present in supernatants of DENV-infected THP-1 cells increase HMVEC adhesion molecules and this induction corresponds with increased permeability at 16 and 24 h.

Fig. 2.

Supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cells increase HMVEC adhesion molecules and permeability. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel mRNA fold-change in HMVEC treated for 16 h with supernatants from control or infected THP-1 cells collected at day 1 (D1 Sup) and day 3 (D3 Sup) after infection or 24 h after LPS treatment. As positive controls, HMVEC were treated for 16 h with the supernatants from LPS treated THP-1 cells or incubated directly with 200 pg of IL-1β. GAPDH was used as the endogenous control. (B) Western blot analysis of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel expression on HMVEC monolayers seeded on 12-well culture plates and treated for 16 h with supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cells. The control supernatants are from mock-infected (UV-treated DENV) THP-1 cells while the infected supernatants are from DENV-infected THP-1 cells both collected at day 1 and day 3 after infection. As a positive control, HMVEC were treated directly with 200 pg of IL-1β and β-actin was used as an endogenous control. (C) To determine the permeability potential of DENV-infected THP-1 supernatants, TEER and FITC-dextran crossing the PET membrane were determined as described in Fig. 1 and in the materials and methods section. Before treatment, supernatants were UV-treated to inactivate viable virus. As positive controls, 0.5 ng/mL of TNFα or supernatants from LPS treated THP-1 cells were used. Data are presented as percent of non-treated control membranes and bars represent the mean ± SD of two independent experiments in triplicate. (*) indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05 as compared to controls.

DENV-infected HMVEC do not increase expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 or E-sel nor increase permeability levels

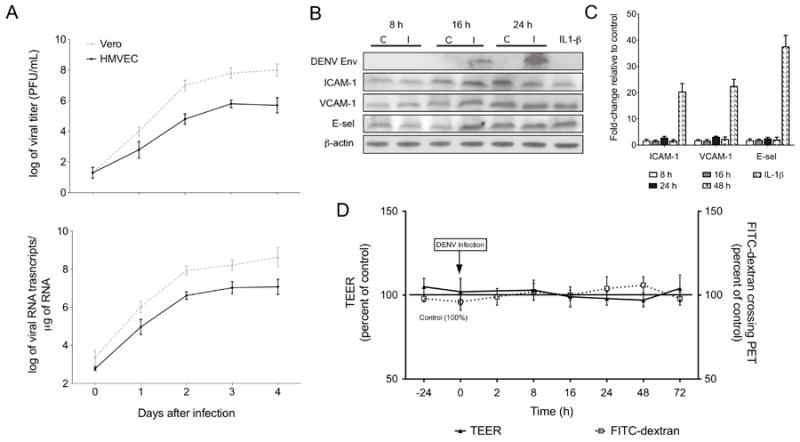

Human endothelial cells are susceptible to DENV infection (Andrews et al., 1978; Arevalo et al., 2009). However, other investigators have demonstrated that DENV-infected endothelial cells in-vitro do not increase permeability (Bonner and O’Sullivan, 1998; Dewi, Takasaki, and Kurane, 2004) or expression of adhesion molecules (Anderson et al., 1997). Since we demonstrated HMVEC phenotypic changes upon treatment with UV-treated supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cells, we wanted to ensure that DENV infection per se does not lead to the observed HMVEC phenotypic changes. Therefore, we infected HMVEC monolayers with DENV MOI-1 and measured DENV replication kinetics by plaque assay and qRT-PCR. On day 3 after infection, maximum viable virus released was log 5 PFU/mL and copy numbers reached approximately log 7 viral RNA transcripts/μg of RNA (Fig. 3A). Given that other investigators have demonstrated that DENV-infected large vessel human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) increase IL-6 and IL-8 expression, which may regulate adhesion molecule expression via autocrine induction, we assessed using the Luminex® multiplex technology whether DENV-infected HMVEC increased the production of immunomediators. On or before day 3 after infection of HMVEC with DENV, IL-6 (115 pg/mL, p=0.12) and IL-8 (852 pg/mL, p=0.09) levels were slightly increased compared to control cells (85 pg/mL and 634 pg/mL, respectively), but these increases were not statistically significant (Table 1). Importantly, we did not detect TNFα or IFNγ in the supernatants from either mock-infected control or DENV-infected HMVEC. As demonstrated by western blot, the expression of DENV envelope gene was detected at 16 and 24 h after infection. However, ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel protein expression did not increase at 8, 16 or 24 h after infection (Fig. 3B). These data were confirmed by qRT-PCR wherein ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel mRNA transcript changes in DENV-infected HMVEC were below the 2-fold cutoff relative to controls at 8, 16, 24, and 48 h after infection (Fig. 3C). To determine if DENV-infected HMVEC increased permeability, we infected HMVEC with DENV MOI-1 directly on the transwell permeability model and measured TEER and FITC-dextran crossing the membrane. We observed no significant permeability changes for up to 72 h after infection (Fig. 3D) even though we demonstrated by plaque assay data a steady increase in viable virus released from the infected permeability model, reaching approximately log 4 PFU/mL at 72 h after infection (data not shown). Overall, these data suggest that DENV infection per se does not modulate HMVEC adhesion molecule expression or alter the HMVEC phenotype based on the permeability assay. However, the immunomediators secreted in the supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 monocytes are primarily responsible for the observed phenotypic changes.

Fig. 3.

DENV-infected HMVEC do not increase expression of adhesion molecules or permeability. HMVEC cells were seeded on 12-well culture plates or 24-well Transwell inserts as described in Fig. 2 and were infected with DENV-2 NGC strain at an MOI-1 to evaluate replication kinetics, adhesion molecule expression and permeability changes. (A) HMVEC or Vero cells were infected with DENV with an MOI-1 and cells and supernatants were collected each day for four consecutive days. Viral titers and RNA copy numbers were determined by plaque assay and qRT-PCR, respectively, on samples collected each day after infection (HMVEC, solid line; Vero cells, dotted line). (B) Western blot analysis of DENV envelope, ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel expression levels on mock-infected and DENV-infected HMVEC harvested at 8, 16, and 24 h after infection. As a positive control, HMVEC were treated directly with 200 pg of IL-1β for 8 h (ICAM-1) or 16 h (VCAM-1 and E-sel) and β-actin was used as an endogenous control. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel mRNA fold-change in DENV-infected HMVEC compared to same time point controls harvested at 8, 16, and 24 and 48 h after infection. HMVEC directly incubated with 200 pg of IL-1β for 8 h (ICAM-1) or 16 h (VCAM-1 and E-sel) are positive controls and GAPDH was used as the endogenous control. (D) HMVEC were seeded on PET-fibronectin membranes and infected with DENV. The percent change of TEER (solid line) and FITC-dextran crossing the membrane (dotted line) were measured for up to 72 h after infection. Bars represent the mean ± SD of at least six samples.

Table 1.

Immunomediators detected in the supernatants of DENV-infected primary HMVEC cells.

| IFNγ

|

TNFα

|

IL-6

|

IL-8

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meana |

SDb |

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD

|

|

| 8 h control supernatantd | NDc | -- | ND | -- | 61 | 8.9 | 571 | 113 |

| 8 h DENV supernatante | ND | -- | ND | -- | 84 | 12 | 691 | 146 |

| Day 1 control supernatantd | ND | -- | ND | -- | 86 | 26 | 621 | 106 |

| Day 1 DENV supernatante | ND | -- | ND | -- | 104 | 35 | 893 | 135 |

| Day 3 control supernatantd | ND | -- | ND | -- | 85 | 10 | 634 | 99 |

| Day 3 DENV supernatante | ND | -- | ND | -- | 115 | 19 | 852 | 116 |

pg/ml; n ≥ 4 samples from at least 2 experiments

SD = standard deviation

ND = not detected

Supernatant from HMVEC cells infected with UV-treated DENV NGC at MOI 1

Supernatant from HMVEC cells infected with DENV NGC at MOI 1

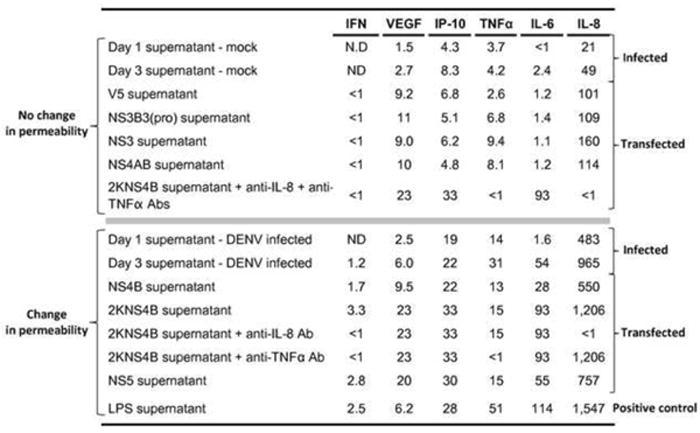

Maturation of NS4B in THP-1 monocytes induces immunomediators sufficient to alter HMVEC adhesion molecules and permeability

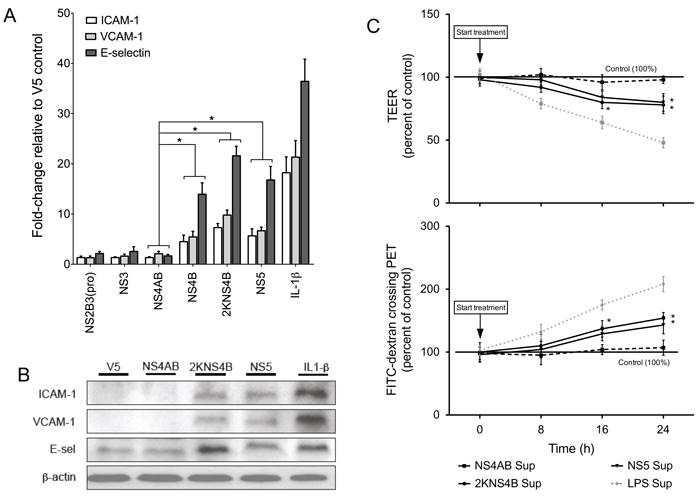

We previously demonstrated that maturation of NS4B, via cleavage of 2KNS4B by host proteases, significantly enhanced the production of immunomediators compared to levels induced by NS5, which also significantly induced immunomediators compared to the V5 vector control (Kelley et al., 2011). Using the Luminex® multiplex technology, we quantitated immunomediators secreted in the supernatants of THP-1 cells expressing DENV NS proteins (Table 2). Given that immunomediator levels found in the supernatants of THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B were significantly elevated (Supplemental Table 1), we expected that supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B would modulate HMVEC adhesion molecules and permeability. Using HMVEC monolayers, we demonstrated that the supernatant from THP-1 cells expressing NS4B, 2KNS4B or NS5 significantly induce ICAM-1 (8 h after treatment), and VCAM-1 and E-sel (16 h after treatment) mRNA transcripts relative to levels induced by the supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing the V5 control vector (Fig. 4A). Supernatants from monocytes expressing 2KNS4B induced maximum levels of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel reaching 8-, 11- and 23-fold respectively relative to the V5 control, which were significantly higher than levels induced by the supernatant from THP-1 cells expressing NS4AB (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). Western blot data confirmed that the supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B or NS5 increased ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel protein expression compared to the supernatant from THP-1 cells expressing V5 or NS4AB proteins (Fig. 4B). When we tested for permeability changes, we observed that the supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B significantly increased permeability compared to the supernatant from NS4AB at 16 and 24 h after treatment using both TEER and FITC-dextran assays, by approximately 25% and 140% compared to controls, respectively (Fig. 4C). Overall, we demonstrate that maturation of NS4B via cleavage of 2KNS4B in THP-1 cells is capable of inducing a significant quantity of immunomediators, which induce the expression of HMVEC adhesion molecules and permeability.

Table 2.

Immunomediators present in the supernatants of THP-1 cells expressing DENV NS proteins.

| IFNγ

|

VEGF

|

IP-10

|

TNFα

|

IL-6

|

IL-8

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meana |

SDb |

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Mean

|

SD

|

|

| No pDNA supernatantc | 1.7 | 0.5 | 17 | 4.7 | 13 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 241 | 116 |

| V5 supernatantd | 1.5 | 0.4 | 18 | 6.4 | 14 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 202 | 65 |

| NS3B3(pro) supernatantd | 1.8 | 0.2 | 22 | 1.4 | 10 | 6.2 | 11 | 7.8 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 218 | 145 |

| NS3 supernatantd | 1.4 | 0.4 | 18 | 7.1 | 12 | 7.1 | 14 | 7.3 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 319 | 130 |

| NS4AB supernatantd | 1.3 | 0.6 | 20 | 3.5 | 9.6 | 6.4 | 12 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 229 | 91 |

| NS4B supernatantd | 3.4 | 1.2 | 19 | 13 | 44* | 9.7 | 2.7 | 9.5 | 57* | 17 | 1,100* | 449 |

| 2KNS4B supernatantd | 6.5* | 0.7 | 46 | 11 | 65* | 15 | 30 | 13 | 185§ | 36 | 2,413§ | 382 |

| NS5 supernatantd | 5.6* | 1.0 | 40 | 14 | 59* | 13 | 29 | 11 | 109* | 30 | 1,513* | 393 |

| LPS supernatant | 6.2 | 0.9 | 20 | 8.9 | 63 | 9.9 | 115 | 12 | 223 | 19 | 3,109 | 267 |

pg/ml n ≥ 6 samples from at least 3 experiments

SD = standard deviation

Supernatant from THP-1 cells electroporated without pDNA

Supernatant from THP-1 cells electroporated with specified pDNA

Statistical significance (p < 0.05) compared to V5 pDNA control

Statistical significance (p < 0.05) compared to NS5 pDNA sample

Fig. 4.

Immunomediators secreted by THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B or NS5 proteins promote endothelial cell activation and permeability. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel mRNA fold-change from HMVEC after treatment with supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing DENV NS2B3(pro), NS3, NS4AB, NS4B, 2KNS4B or NS5 or incubated with 200 pg of IL-1β. Values for ICAM-1 (8 h after treatment) and VCAM-1 and E-sel (16 h after treatment) are normalized to expression levels induced by supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing V5 control epitope. GAPDH is the endogenous control and (*) indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05 as compared to values determined for NS4AB. (B) Western blot analysis of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel on HMVEC after treatment with supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing DENV NS4AB, 2KNS4B or NS5 or V5 control. HMVEC were harvested at 8 h (ICAM-1) or 16 h (VCAM-1 and E-sel) after treatment. As a positive control, HMVEC were treated directly with 200 pg of IL-1β and β-actin is shown as the endogenous control. (C) HMVEC were seeded on PET-fibronectin membranes and incubated with supernatants described in Fig. 3A. The percent change of TEER and FITC-dextran crossing the membrane were measured for supernatant from THP-1 cells expressing NS4AB, 2KNS4B and NS5. The supernatant from LPS treated THP-1 cells was used as a positive control (dotted grey line). Bars represent the mean ± SD of at least four samples. (*) indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05 as compared to controls.

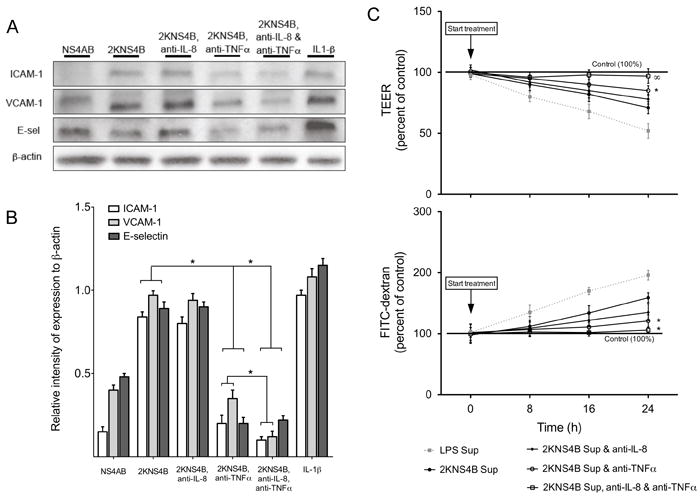

TNFα and IL-8 synergistically modulate HMVEC adhesion molecules and permeability

TNFα effectively increases the expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel in HUVEC (Anderson et al., 1997). Moreover, TNFα at concentrations ranging from 10 pg/mL to 10 μg/mL (Carr et al., 2003; Dewi, Takasaki, and Kurane, 2004; Gibbs, Lai, and Malik, 1990; Marcus et al., 1996; Nooteboom et al., 2000) and IL-8 at concentrations ranging from 50 ng/mL to 1 μg/mL (Biffl et al., 1995; Petreaca et al., 2007) can modulate endothelial cell permeability depending on the permeability model used for the assay. In contrast, Beyon and colleagues have demonstrated that low concentrations of immunomediators in combination synergistically alter adhesion molecules and permeability when compared to addition of individual recombinant chemokines or cytokines (Beynon et al., 1993). Since the supernatants from THP-1 cells infected with DENV or expressing individual NS proteins consist of an array of immunomediators, we hypothesized that TNFα and IL-8 modulate adhesion molecule changes or permeability. To test this hypothesis, we incubated the supernatant of DENV infected or transfected THP-1 cells with neutralizing antibodies against TNFα and IL-8 prior to incubating the supernatant with HMVEC. Of note, using Luminex technology we demonstrated that in the neutralizing antibodies treated supernatants, the levels of TNFα and IL-8 were in the nondetectable range: 0.2 and 0.3 pg/mL for TNFα and IL-8, respectively. Upon neutralizing IL-8 in the supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B and incubation on HMVEC, we observed using western blot that there was no reduction of HMVEC adhesion molecule expression levels compared to the effects caused by the supernatants without neutralizing IL-8 antibodies (Fig. 5A-B). However, we did observe a slight reduction in TEER or FITC-dextran crossing the permeability membrane but the changes were not significant (Fig. 5C). When we neutralized TNFα, we observed a significant reduction of adhesion molecule expression levels by western blot (Fig. 5A-B). Moreover, HMVEC membrane permeability significantly decreased after TNFα neutralization as demonstrated by TEER reduction from approximately 25 to 12% and FITC-dextran crossing decrease from 150 to 115% of levels caused by 2KNS4B supernatants without TNFα antibodies (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, when we neutralized TNFα and IL-8 together and treated HMVEC, we observed an enhanced reduction of adhesion molecule expression by western blot (Fig. 5A-B) and significantly decreased membrane permeability levels compared to samples treated with TNFα neutralizing antibodies alone, as measured by TEER (Fig. 5C). Overall, these data suggest that TNFα and IL-8 may synergistically increase ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel expression and induce phenotypic changes based on the permeability assay in HMVEC.

Fig. 5.

Neutralization of TNFα and IL-8 secreted by 2KNS4B protein expressing THP-1 cells inhibits HMVEC-activation and -permeability. Neutralizing antibodies against TNFα or IL-8 were incubated with the supernatant from THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B and Western blot, and permeability assays were conducted using the neutralized supernatant. (A) Western blot analysis of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel using HMVEC treated with supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing NS4AB, 2KNS4B, or supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B incubated with neutralizing antibodies against TNFα or IL-8 or TNFα and IL-8. HMVEC were harvested at 8 h (ICAM-1) or 16 h (VCAM-1 and E-sel) after treatment. β-actin was employed as an endogenous marker. (B) Percent relative intensity of Western blot test samples compared to relative intensity of positive control IL-1β. Relative intensity was calculated by dividing the absolute intensity of the adhesion molecule protein band by the absolute intensity of its corresponding β-actin band. Relative intensities of the positive control were then divided by each sample. (*) indicates a statistically significant reduction in relative intensities. (C) HMVEC were seeded on PET-fibronectin membranes and incubated with supernatants from Fig. 4A and as described in Fig. 1C except without UV-irradiation. The percent change of TEER and FITC-dextran crossing the membrane were measured. The supernatant from LPS treated THP-1 cells was used as a positive control (dotted grey line). (*) indicates a statistically significant reduction compared to supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B and (∞) indicates a statistically significant reduction in premeability compared to supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B and treated with anti-TNFα neutralizing antibody, both at p < 0.05. Bars represent the mean ± SD of at least four samples.

A minimum dose of TNFα or IL-8 is required to modulate HMVEC adhesion molecules or permeability changes

We utilized in-vitro models that mimic a natural infection environment in order to effectively control for and identify individual immunomediators associated with HMVEC adhesion molecule expression and permeability. Our previously published data provided immunomediator concentrations (Kelley et al., 2011) which correspond to the initiation of DHF-associated phenotypes in our HMVEC models. Based on our HMVEC model treatment dilution strategy of 1:1 (endothelial cell medium to supernatant from treated THP-1 cells), we were able to quantitate minimum functional mean concentrations of the immunomediators required to increase HMVEC permeability (Table 3). The supernatants, from transfected or infected THP-1 cells, were categorized based on their ability to change HMVEC permeability and expressed as pg/mL. Minimum immunomediator levels able to increase permeability were from supernatants collected at day 1 after DENV infection, wherein TNFα levels were 14 pg/mL and IL-8 levels were 483 pg/mL (Table 3). Supernatants having < 9.5 pg/mL of TNFα in combination with < 160 pg/mL of IL-8 were unable to increase permeability. Of note, VEGF was not significantly different for the two groups while IP-10 and IL-6 levels were elevated in the supernatants that increased permeability even though they appeared to have no direct effect when TNFα and IL-8 were neutralized (Table 3). Given that clinical samples from DHF/DSS patients demonstrate elevated levels of TNFα and IL-8, these data and models may provide a means to better understand threshold cutoff levels of vasoactive mediators found during DHF/DSS.

Table 3.

Threshold dose levels of chemokines and cytokines that induce HMVEC adhesion molecule and permeability changes.

|

Discussion

Although the mechanisms by which DENV causes severe disease are not clearly defined, DHF/DSS is associated with elevated levels of chemokines and cytokines that over-stimulate vascular endothelial cells leading to expression of adhesion molecules, increased permeability and ultimately irreversible endothelial cell dysfunction (Beynon et al., 1993; Kurane, 2007). Due to the lack of ideal animal models to study DHF immunopathogenesis, we used human microvascular endothelial cells to assess alterations associated with DHF/DSS, including adhesion molecules expression and membrane permeability. Previous studies have employed various types of endothelial cells to develop membrane permeability model systems with variable results (Beynon et al., 1993; Bonner and O’Sullivan, 1998; Carr et al., 2003; Dewi, Takasaki, and Kurane, 2004; Jacobs and Levin, 2002; Talavera et al., 2004). Additionally, DENV infection or transfection experiments conducted independently to study the effects of induced immunomediators, made it difficult to summarize and conclude the role of these immunomediators in DENV immunopathogenesis (Anderson et al., 1997; Biffl et al., 1995; Carr et al., 2003; Medin, Fitzgerald, and Rothman, 2005).

Unlike previous reports, in this study we collectively demonstrate for the first time in a single HMVEC experimental system used to measure both permeability and expression changes of adhesion molecules, that DENV-infected THP-1 cells and transfected THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B, produce IL-8 and TNFα levels sufficient to increase HMVEC permeability, which corresponds to increased adhesion molecules expression. Moreover, we demonstrate that these HMVEC phenotypic changes appear to be caused primarily by monocyte-derived TNFα, and to a lesser extent IL-8, rather than direct DENV infection of HMVEC, which is consistent with histopathological studies demonstrating low or nonexistent infection of endothelial cells in DHF/DSS patients (Halstead, 1989). By using quantitative Luminex data, we further demonstrate that a minimum level of TNFα and IL-8 is required for HMVEC activation or increased permeability, suggesting that therapies blocking the maturation of NS4B and subsequent production of vasoactive mediators, or circulating TNFα and/or IL-8, may prevent DHF/DSS.

Immunomediators in the supernatants of DENV-infected THP-1 monocytes increase HMVEC adhesion molecules and permeability

Published data demonstrate that DENV, in the presence of sub-neutralizing antibodies, infects monocytes and produces immunomediators, particularly TNFα, which are responsible for initiating and sustaining increased vascular endothelial cell permeability (Carr et al., 2003); whereas TNFα and IL-1β are the primary stimulatory molecules for ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel (Anderson et al., 1997; Cardier et al., 2005; Detmar et al., 1992; Wyble et al., 1996). Anderson et al demonstrated that ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 had the greatest expression levels 16 h after HUVEC treatment whereas E-sel appeared to be more transient, as indicated by its detection at 3 h after treatment (Anderson et al., 1997). In contrast, we demonstrate increased VCAM-1 and E-sel at 16 h while ICAM-1 peaked at 8 h after treatment of small vascular HMVEC. Because vascular endothelial cells are highly organized and physiologically specialized, experimental differences observed between HMVEC and HUVEC are most likely due to differences in cell function. In fact, published data indicate that differences in adhesion molecule expression levels depend on the vascular cell bed of origin (De Staercke, Phillips, and Hooper, 2003; Elherik, Khan, and Belch, 2003; Gerritsen et al., 1993), emphasizing the complexity of vascular endothelial cell function in-vivo.

Increased vascular permeability and plasma leakage found during DHF/DSS pathogenesis occur at defervescence when immunomediator levels are elevated and viremia has decreased (Iyngkaran, Yadav, and Sinniah, 1995; Kurane and Takasaki, 2001; Leong et al., 2007; Libraty et al., 2002; Nguyen et al., 2004; Priyadarshini et al., 2010). Although many cell types can produce immunomediators, supernatants from monocytes or monocyte-derived macrophages infected with DENV or other viruses that cause systemic hemorrhaging, such as Marburg virus, increase HUVEC permeability (Carr et al., 2003; Feldmann et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2006). In this report, we demonstrate that DENV-infected THP-1 monocytes secrete sufficient levels of immunomediators to increase HMVEC permeability. The observed increase in permeability begins at 8 h after treatment, when ICAM-1 levels are highest, and peaks at 24 hours after treatment. Interestingly, cytokine-induced permeability changes occur after adhesion molecule expression and possibly in part due to ICAM-1 mediated signaling (Marcus et al., 1996; Sumagin, Lomakina, and Sarelius, 2008). Persistent over-expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules can weaken tight junction proteins (Kanlaya et al., 2009; Nooteboom et al., 2000; Talavera et al., 2004) and prolong vascular permeability via cytoskeleton reorganization and endothelial cell shape change (Clark et al., 2007; Marcus et al., 1996; Sumagin, Lomakina, and Sarelius, 2008). One of the primary functions of in-vivo adhesion molecules expression is leukocyte extravasation from the periphery to interstitial sites of infection. As adhesion molecules undergo sustained expression during infection, it is probable that increased levels of infiltrating leukocytes compound vascular endothelial cell permeability as they release vasoactive molecules as part of the innate immune response. In fact, others demonstrate that increased HUVEC permeability begins at 6 h after treatment with TNFα, and after maximum expression of another adhesion molecule, endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule-1 (ELAM-1) at 4 h (Marcus et al., 1996). Also, TNFα alone, albeit five times the concentration as in the supernatant from LPS-treated THP-1 cells, appears to increase permeability much more effectively than the supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cells, suggesting a dose dependent effect on permeability. Together, these data establish that the mediators present in the supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cells increase HMVEC permeability, which corresponds with ICAM-1 expression at 8 h after treatment; and that TNFα, with other mediators, may be a potent inducer of HMVEC phenotypic changes.

DENV-infected HMVEC do not increase expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 or E-sel nor increase permeability levels

DENV and other viruses, such as Ebola virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus and Hantavirus, are associated with hemorrhagic diseases, yet the mechanisms defining their underlying pathology remain unclear. Ebola virus, a filovirus, replicates efficiently in endothelial cells and produce a destructive infection in-vitro which parallels endothelial cell lysis observed in infected humans (Fisher-Hoch et al., 1985; Salvaggio and Baddley, 2004). In contrast, DENV is able to efficiently replicate in HUVEC and HMVEC in-vitro but histopathological studies indicate low or nonexistent infection of endothelial cells as well as little structural damage to capillaries in tissue from DHF/DSS patients (Bhamarapravati, Tuchinda, and Boonyapaknavik, 1967; Halstead, 1988; Halstead, 1989; Sahaphong et al., 1980). The paucity of clinical data on infection of endothelial cells makes it difficult to discern their susceptibility during progression of DHF/DSS. However, recently published data indicating absence of infectious DENV particles in moribund mice exclude a direct virus cytopathic effect and suggest some immunological disorder due to overstimulation of immune cells possibly by persistent viral antigens (Tan et al., 2010). Moreover, as we and others demonstrate, DENV-infected HMVEC do not increase adhesion molecules or permeability (Anderson et al., 1997; Bonner and O’Sullivan, 1998; Carr et al., 2003; Chareonsirisuthigul, Kalayanarooj, and Ubol, 2007) suggesting a probable role of soluble vasoactive mediators on the induction of phenotypic changes rather than DENV infection of endothelial cells. Even though both DENV-infected endothelial cells and mock-infected controls produce fairly high endogenous levels of IL-8, TNFα was not secreted, suggesting that endothelial cells are most likely not the source of TNFα. Collectively, based on published clinical data and our in-vitro data, we postulate that the infection of immune cells and release of toxic levels of immunomediators may lead to dysfunctional endothelium including capillary leakage. Although this explains only part of the conundrum surrounding the contribution of monocytes and the window period between viremia and DHF progression, many facts remain to be proven including the contribution of other cell types during immunomediator production and levels of immunomediators from disease onset to DHF/DSS.

Maturation of NS4B in THP-1 cells produces TNFα and IL-8, which increase HMVEC permeability

Previously we demonstrated that monocytes expressing the 2KNS4B protein significantly increase immunomediator production compared to levels induced by NS5. As such, we examined the ability of supernatants from monocytes expressing NS proteins to increase adhesion molecules and permeability. We demonstrated that expression of either NS5 or 2KNS4B induces sufficient mediators to increase adhesion molecules and permeability, while 2KNS4B has a slightly greater effect. TNFα is a well-known potent endothelial cell activating factor, increasing HUVEC adhesion molecule expression (Anderson et al., 1997) and HMVEC permeability (Carr et al., 2003; Pober and Cotran, 1990). Other researchers conducting TNFα blocking experiments demonstrate a significant reduction of HMVEC ICAM-1 expression as induced by dengue patient sera (Cardier et al., 2005). Moreover, two independent mouse models of dengue infections confirm the association of TNFα with disease severity, which was attenuated using neutralizing TNFα antibodies (Atrasheuskaya et al., 2003; Shresta et al., 2005). IL-8 alone can induce permeability at high concentrations (Biffl et al., 1995; Petreaca et al., 2007; Talavera et al., 2004) as demonstrated during our permeability model optimization experiments. Herein, we demonstrate using neutralizing antibodies that primarily TNFα, and secondarily IL-8, increase permeability and adhesion molecules. The combined effect appears to be synergistic, as when we neutralize both TNFα and IL-8 in the supernatants from THP-1 cells expressing 2KNS4B permeability is significantly reduced, more than the sum of the effect caused by IL-8 and TNFα. This effect may be due to increased induction of molecules associated with intracellular signaling pathways but the exact mechanism remains unclear. Overall, these data suggest that TNFα is primarily responsible for increasing expression of adhesion molecules and permeability, while IL-8 may play a synergistic role (Carr et al., 2003; Dewi, Takasaki, and Kurane, 2004; Dhawan, Singh, and Aggarwal, 1997). Moreover, maturation of NS4B via cleavage of the 2K-signal peptide is sufficient to induce mediators capable of inducing endothelial cell phenotypic changes associated with severe DHF/DSS.

A minimum level of TNFα or IL-8 is required to increase HMVEC adhesion molecules or permeability changes

It has been postulated that elevated immunomediators are responsible for sustained endothelial cell changes during severe DHF/DSS. It is plausible that a threshold level of chemokines and cytokines, particularly TNFα and IL-8, is needed to modulate endothelial cell phenotypic changes during disease progression. Indeed, we demonstrate that supernatants having at least a two-fold higher level of TNFα and a four-fold higher level of IL-8, while maintaining similar levels of VEGF, IP-10 and IL-6, increase membrane permeability. Moreover, HMVEC treated with high amounts of individual positive controls, TNFα or IL-8, increase permeability but require over 50 or 8 times higher levels, respectively, than supernatants having lower levels but combinations of several immunomediators. Low levels of vasoactive mediators more effectively increase permeability than individual mediators (Beynon et al., 1993) and TNFα, IFNγ and IL-1 together induce a greater increase in permeability compared to individual cytokines (Burke-Gaffney and Keenan, 1993). Also, it is well known that even low levels of cytokines can induce the production of other cytokines, suggesting that a complex and interactive immunomediator induction network exists which may further facilitate increased mediators involved in DHF/DSS immunopathogenesis (Kurane et al., 1994).

Other than the direct TNFα-mediated permeability, TNFα can activate the production of lipid mediators including platelet-activating factor (PAF), leukotrienes and prostaglandins, all of which can act as potent activators of permeability (Lefer, 1989). While control patients’ sera demonstrate mean TNFα levels of 10 pg/mL, sera from DF and DHF patients reach 220 and 239 pg/mL respectively (Chakravarti and Kumaria, 2006). Another study from Brazil demonstrates that sera from DF patients have a mean TNFα level of approximately 28 pg/mL and sera from DHF patients have 128 pg/mL (Braga et al., 2001). Moreover, circulating soluble TNF receptors have been associated in children with DHF, correlating with subsequent shock (Bethell et al., 1998). Given that macrophages, mast cells, natural killer cells, T- and B-cells and other cells produce TNFα, we are unable to correlate clinical estimates. However, our data and others suggest that reduction of vasoactive mediators, specifically TNFα, in DENV-infected patients may minimize the risk of DHF/DSS progression.

Conclusions

Although the mechanisms by which DENV causes severe disease are not clearly defined, DHF/DSS is associated with elevated levels of TNFα and other chemokines and cytokines, secreted in part by infected monocytes, that can cause irreversible endothelial cell dysfunction (Beynon et al., 1993; Kurane, 2007). We have previously demonstrated that DENV, primarily via maturation of NS4B and sequential processing of 2KNS4B, induces DHF-associated immunomediators in THP-1 cells (Kelley et al., 2011). Herein we demonstrate that immunomediators levels induced by 2KNS4B are sufficient to initiate DHF-associated phenotypic changes, including HMVEC permeability and adhesion molecule expression changes. Also, we demonstrate that HMVEC phenotypic changes appear to be caused primarily by TNFα (and IL-8) rather than direct DENV infection of HMVEC. It appears that a minimum level of TNFα and IL-8 is required during HMVEC activation or permeability. Based on these data, antiviral therapies that block the maturation of NS4B or TNFα inhibitors that reduce elevated levels of TNFα may prevent the progression of DHF/DSS.

Materials and Methods

Virus, cell culture, supernatants from THP-1 cells and other reagents

We employed a low passage DENV-2 NGC strain (obtained from Dr. Duane Gubler at the University of Hawaii at Manoa) propagated in C6/36 cells to infect primary HMVEC and Vero (monkey kidney epithelial) cells (Kelley et al., 2011). For mock-infection, control virus was inactivated by UV-light irradiation for 10 minutes. For the endothelial cell activation and permeability experiments, we employed primary HMVEC purchased from the Lonza Group Ltd. (Basal, Switzerland). As per the manufacturer’s technical sheet, HMVEC stain positive for acetylated LDL and von Willebrand’s (Factor VIII) antigen and stain negative for smooth muscle α-actin. HMVEC were received at passage 3 and grown in endothelial cell growth medium EGM-2-MV and SingleQuot® growth supplements including, bovine brain extract with heparin, hEGF, hydrocortisone, gentamicin, amphotericin B, and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Lonza). All experiments were conducted using HMVEC passage 5. The Vero cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD) and maintained in minimum essential medium Eagle (MEME) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10 μg/mL gentamicin (Gibco Labs, Grand Island, NY). Both cell types were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and the growth media was changed every two or three days. The supernatants used to treat the endothelial cells were collected from THP-1 cells of monocytic lineage (ATCC) either infected with DENV at MOI-1, treated with 1 μg/mL of LPS for 1 h, washed and incubated with fresh growth media until collection after 24 h, or cells expressing individual DENV nonstructural proteins (NS) as described previously (Kelley et al., 2011). For positive controls we used recombinant TNFα, IL-8, or IL-1β proteins and to neutralize immunomediators, we used antibodies against TNFα and IL-8 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). For experiments involving neutralizing antibodies, cells were washed, and media was changed to 10% heat-inactivated FBS DMEM before antibody treatment.

Infection of HMVEC and Vero cells

The DENV2 NGC strain was used to infect 1 × 106 HMVEC or Vero cells in 12-well tissue culture plates or 1 × 105 HMVEC cells on fibronectin-coated polyethylene terephthalate (PET) 24-well insert membranes at MOI-1. After 1.5 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, the cells were washed twice with fresh growth media and further cultured with growth medium. For the mock-infected controls, we inoculated HMVEC with UV-inactivated DENV, as described previously (Verma et al., 2009). As a positive control for adhesion molecule experiments, 1 × 106 HMVEC were incubated with 200 pg of IL-1β for 1 h, washed and incubated with fresh growth media until collection at 8 h after incubation for detection of ICAM-1 and 16 h after incubation for detection of VCAM-1 and E-sel. Every 24 h, cells and supernatants were collected while remaining cells were replenished with fresh growth media. Viable virus released from infected cells was confirmed by plaque assay as described below.

Plaque assay

To determine the amount of infectious virus released from DENV-infected THP-1 cells, plaque assay was conducted using Vero cell monolayers as described previously (Lambeth et al., 2005). Briefly, 2.5 × 105 Vero cells per well were seeded in 6-well culture plates (Corning, Lowell, MA) and incubated for 2 to 3 days until confluent. Supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cells were serially diluted using 10-fold dilutions in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) (Gibco Labs) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 μL of each dilution was added to each well of the Vero cells followed by incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1 h with rocking every 15 minutes. Three mL of primary nutrient agar containing 1% SeaKem® LE agarose (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for 5 days. Three mL of secondary nutrient agar (primary agar containing 1% neutral red) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for an additional two days before counting plaques and calculating viral titers (Kelley et al., 2011; Lambeth et al., 2005). Titers were expressed as plaque forming units (PFU)/mL.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total cellular RNA was extracted as per manufacturers’ protocol (RNeasy® Plus kit with RNase-Free DNase, Qiagen) from DENV-infected HMVEC harvested at different time points. cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of RNA using the BioRad iScript® kit in a 20 μL reaction volume. BioRad iCycler iQ™ Multicolor Real-Time PCR Detection System was employed to conduct qRT-PCR for quantitation of DENV copy numbers or ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-sel genes using Bio-Rad iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix, 2 μL of 1:3 diluted cDNA, and 10 pmol each of forward and reverse primers (Table 4) in a final reaction volume of 20 μL. Thermal cycling reactions for both DENV and adhesion molecule amplifications were initiated with a denaturing step of 4 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C (30 sec) and a range of 55-60°C (30 sec) depending on the Tm (Table 4). A standard curve to measure DENV copies was developed from 10-fold serial dilutions of linear DENV gene having known concentrations to quantitate the dynamic range of detection of 102 to 108 copies per μg of RNA. Host cellular gene changes relative to the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) housekeeping gene were determined as previously described (Kelley et al., 2011; Verma et al., 2006). Primers used to measure cellular gene changes are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Primers employed for the analysis of DENV and host genes by qRT-PCR.

| Gene (GenBank no.) | Primer Sequence (5’ - 3’) | Tm (°C) | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DENV Capsida | |||

|

| |||

| Forward | CAATATGCTGAAACGCGAGAG | 60 | 167 |

| Reverse | CATCTATTCAGAATCCCTGCT | ||

|

| |||

| ICAM-1 (NM_002162)b | |||

|

| |||

| Forward | AGCGGCAGTTACCATGTTAGGG | 58 | 146 |

| Reverse | GGCTTTATTGGTGCGGAATCTGA | ||

|

| |||

| VCAM-1(BC068490)b | |||

|

| |||

| Forward | TGCTGCTCAGATTGGAGACTC | 55 | 113 |

| Reverse | TCCTCACCTTCCCGCTCAG | ||

|

| |||

| E-selectin (NM_000450)b | |||

|

| |||

| Forward | TGAGACAGAGGCAGCAGTG | 57 | 199 |

| Reverse | CCGTGGAGGTGTTGTAAGAC | ||

|

| |||

| GAPDH (BC025925)b | |||

|

| |||

| Forward | AGTTAGCCGCATCTTCTTTTGC | 57 | 96 |

| Reverse | CAATACGACCAAATCCGTTGACT | ||

Real-time PCR primers to determine DENV2 NGC copy numbers

Real-time RT-PCR primers to amplify adhesion molecule genes or GAPDH endogenous control

In-vitro permeability model

We constructed the in-vitro permeability model using Millipore Biocoat® cell culture inserts with fibronectin-coated PET membranes with 3 μm pores and 0.33 cm2 diameter (BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA) as described previously (Verma et al., 2009). Briefly, after rehydrating the inserts in warm culture medium, 1 × 105 HMVEC in 250 μl fresh medium were seeded in the upper chamber and 1 mL medium was added to the lower chamber of the 24-well insert plate. Further, the inserts were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The integrity of the membranes was measured from days 3 to 15 after seeding HMVEC by using transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) and FITC-dextran (4 KDa mol. wt., Sigma) permeability assays. We choose 4 KDa FITC-dextran based on previous research using primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (Verma et al., 2009). Similarly, TEER was measured using the Endohm chamber (World Precisions, Saratoga, FL) and permeability was calculated as per manufacturers’ protocol (Verma et al., 2009). FITC-dextran crossing the membrane was measured by adding to the upper chamber 250 μl of 100 μg/mL FITC-dextran medium with or without either 0.5 ng/mL of TNFα or 2.5 ng/mL IL-8. Supernatants, 250 μL, from the THP-1 cells were added to the upper chamber and incubated with the HMVEC model at a 1:1 dilution of supernatant in EBM plus 100 μg/mL FITC-dextran for 1.5 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2. Duplicate samples of 150 μL of medium was aliquoted from the lower chamber into a 96-well plate to measure the fluorescence of transmigrated FITC-dextran on a Victor 1420 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA) with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm. The FITC-dextran migration across the membrane was calculated as a percentage of the total amount initially added in the upper chamber and data was calculated as a percent change to untreated control membranes. For DENV infection experiments, HMVEC in the upper chamber were infected with either UV-treated DENV or DENV at MOI-1 beginning at day 6 after seeding, and TEER and FITC-dextran permeability were measured as previously described (Verma et al., 2009).

Cytokine quantitation and conversion into dose treatment values

IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, and IFNγ were measured in the supernatants of DENV-infected HMVEC using a Milliplex human cytokine and chemokine 4-plex immunoassay kit (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) together with the Luminex® 100™ System (Luminex, Austin, TX) to determine mean fluorescent intensities (MFI) as recommended by the manufacturers. Protein concentrations were calculated from MFI data using 10-fold serially-diluted standards and Bead View analysis software version 1.0.4 (Millipore). The minimum detectable concentrations were 0.4 pg/mL for IL-6, 0.3 pg/mL for IL-8, 0.2 pg/mL for TNFα and 0.4 pg/mL for IFNγ. Given that we diluted THP-1 supernatants 1:1 in endothelial cell medium, we divided the given concentrations by half to obtain minimum dose treatment concentration levels in pg/mL (Table 3).

Western blot

Total cellular protein extracts were prepared from HMVEC cells either 8 h after treatment (ICAM-1), 16 h after treatment (VCAM-1 and E-sel) or at otherwise indicated time point. Cells were washed once with cold PBS and extracted with 200 μL of M-PER mammalian protein extraction buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) containing EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Fifty μg in 20 μL of total protein was fractionated on a 4-12% gradient SDS polyacrylamide gel using the Mini-Protean II (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and then transferred onto a 0.2 μm nitrocellulose filter (Bio-Rad Laboratories) as previously described (Verma et al., 2006). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked using 5% FBS in 1x Tris buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Tween (TBST). Membranes were incubated with primary DENV envelope antibody (courtesy of Dr. Wei-Kung Wang, University of Hawaii, detection ~52 KDa) or ICAM-1 mouse monoclonal (band size ~90 KDa), VCAM-1 rabbit polyclonal (band size ~110 KDa), E-sel mouse monoclonal (band size ~150 KDa) or β-actin IgG antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at a 1:1,000 dilution and incubated at 4°C overnight followed by incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated to HRP (dilution 1:5000) at room temperature for 1 h. Proteins bands were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham ECL, GE Healthcare Limited, Buckinghamshire, UK) on Amersham ECL Hyperfilm (Kodak, Rochester, NY). To determine the relative intensity (RI) of protein bands, the absolute intensity of the adhesion molecule protein band was divided by the absolute intensity of its corresponding β-actin band. Absolute intensities were calculated using Photoshop by multiplying the given pixel value and mean intensity of selected bands as previously described (Luhtala and Parker, 2009).

Cell viability assay

To determine the cell viability, control HMVEC or HMVEC were treated with TNFα (0.5 ng/mL), IL-8 (2.5 ng/mL), IL-1β (200 pg/mL) or THP-1 supernatant (1:1 dilution with EBM) or were infected with DENV MOI-1. Briefly, 2 × 104 HMVEC were seeded on 96-well tissue culture plates and after 3 days, triplicate wells of confluent monolayer were incubated with 200 μL of each of the aforementioned treatments for 8, 16, 24 or 48 h, and cell viability was measured using the CellTiter96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) kit as per the manufacturers’ protocol (Verma et al., 2008).

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests, including paired and unpaired Student’s t-tests, were conducted for qRT-PCR and cytokine and chemokine immunoassay using GraphPad InStat version 5.0 (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA). Values were expressed as mean ± SD of at least two independent observations. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Western blot time point analysis of HMVEC ICAM-1 expression. (A) HMVEC were incubated with 200 pg of IL-1β in 12-well tissue culture plates and harvested at predetermined time points. (B) Western blot analysis of HMVEC ICAM-1 expression after incubation for eight hours with supernatants from DENV-infected THP-1 cells as described in Fig. 1A. β-actin was used as an endogenous control.

Cell viability of HMVEC treated with cytokines and cell culture media. HMVEC cells were grown to confluence in 96-well tissue culture plates and cell viability of treated cells was determined by cell proliferation assay. Results are presented as percent change compared to non-treated controls. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Immunomediators detected in the supernatants of DENV-infected THP-1cells.†

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Wei Kung Wang from the Department of Tropical Medicine, Medical Microbiology and Pharmacology at the University of Hawaii for providing the pCprM/pCRII-TOPO DENV plasmid DNA used as a template for the qRT-PCR standards. We thank the staff and students of the Retrovirology Research Laboratory and the Department of Tropical Medicine, Medical Microbiology and Pharmacology for technical assistance. This work was submitted by JFK to the University of Hawaii at Manoa as part of his doctoral thesis project.

This work was supported in part by institutional funds and grants from the Department of Defense (W8IXWH0720073), and Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (P20RR018727) and Research Centers in Minority Institutions Program (G12RR003061), National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson R, Wang S, Osiowy C, Issekutz AC. Activation of endothelial cells via antibody-enhanced dengue virus infection of peripheral blood monocytes. J Virol. 1997;71(6):4226–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4226-4232.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews BS, Theofilopoulos AN, Peters CJ, Loskutoff DJ, Brandt WE, Dixon FJ. Replication of dengue and junin viruses in cultured rabbit and human endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1978;20(3):776–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.20.3.776-781.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo MT, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Kou Z, Schlesinger JJ, Jin X. Primary human endothelial cells support direct but not antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viral infection. J Med Virol. 2009;81(3):519–28. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atrasheuskaya A, Petzelbauer P, Fredeking TM, Ignatyev G. Anti-TNF antibody treatment reduces mortality in experimental dengue virus infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;35(1):33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2003.tb00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avirutnan P, Malasit P, Seliger B, Bhakdi S, Husmann M. Dengue virus infection of human endothelial cells leads to chemokine production, complement activation, and apoptosis. J Immunol. 1998;161(11):6338–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell DB, Flobbe K, Cao XT, Day NP, Pham TP, Buurman WA, Cardosa MJ, White NJ, Kwiatkowski D. Pathophysiologic and prognostic role of cytokines in dengue hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 1998;177(3):778–82. doi: 10.1086/517807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beynon HL, Haskard DO, Davies KA, Haroutunian R, Walport MJ. Combinations of low concentrations of cytokines and acute agonists synergize in increasing the permeability of endothelial monolayers. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;91(2):314–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhamarapravati N, Tuchinda P, Boonyapaknavik V. Pathology of Thailand haemorrhagic fever: a study of 100 autopsy cases. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1967;61(4):500–10. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1967.11686519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffl WL, Moore EE, Moore FA, Carl VS, Franciose RJ, Banerjee A. Interleukin-8 increases endothelial permeability independent of neutrophils. J Trauma. 1995;39(1):98–102. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199507000-00013. discussion 102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner SM, O’Sullivan MA. Endothelial cell monolayers as a model system to investigate dengue shock syndrome. J Virol Methods. 1998;71(2):159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza FA, Cruz OG, Zagne SM, Azeredo EL, Nogueira RM, Assis EF, Bozza PT, Kubelka CF. Multiplex cytokine profile from dengue patients: MIP-1beta and IFN-gamma as predictive factors for severity. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga EL, Moura P, Pinto LM, Ignacio SR, Oliveira MJ, Cordeiro MT, Kubelka CF. Detection of circulant tumor necrosis factor-alpha, soluble tumor necrosis factor p75 and interferon-gamma in Brazilian patients with dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96(2):229–32. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunyaratvej A, Butthep P, Yoksan S, Bhamarapravati N. Dengue viruses induce cell proliferation and morphological changes of endothelial cells. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997;28(Suppl 3):32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke-Gaffney A, Keenan AK. Modulation of human endothelial cell permeability by combinations of the cytokines interleukin-1 alpha/beta, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma. Immunopharmacology. 1993;25(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(93)90025-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardier JE, Marino E, Romano E, Taylor P, Liprandi F, Bosch N, Rothman AL. Proinflammatory factors present in sera from patients with acute dengue infection induce activation and apoptosis of human microvascular endothelial cells: possible role of TNF-alpha in endothelial cell damage in dengue. Cytokine. 2005;30(6):359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JM, Hocking H, Bunting K, Wright PJ, Davidson A, Gamble J, Burrell CJ, Li P. Supernatants from dengue virus type-2 infected macrophages induce permeability changes in endothelial cell monolayers. J Med Virol. 2003;69(4):521–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti A, Kumaria R. Circulating levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha & interferon-gamma in patients with dengue & dengue haemorrhagic fever during an outbreak. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123(1):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CS, Harn MR, Nimmannitya S. Clinical observation of 15 Thai children with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Gaoxiong Yi Xue Ke Xue Za Zhi. 1990;6(3):131–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chareonsirisuthigul T, Kalayanarooj S, Ubol S. Dengue virus (DENV) antibody-dependent enhancement of infection upregulates the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, but suppresses anti-DENV free radical and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, in THP-1 cells. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 2):365–75. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82537-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LC, Shyu HW, Lin HM, Lei HY, Lin YS, Liu HS, Yeh TM. Dengue virus induces thrombomodulin expression in human endothelial cells and monocytes in vitro. J Infect. 2009;58(5):368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark PR, Manes TD, Pober JS, Kluger MS. Increased ICAM-1 expression causes endothelial cell leakiness, cytoskeletal reorganization and junctional alterations. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(4):762–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Staercke C, Phillips DJ, Hooper WC. Differential responses of human umbilical and coronary artery endothelial cells to apoptosis. Endothelium. 2003;10(2):71–8. doi: 10.1080/10623320303369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detmar M, Tenorio S, Hettmannsperger U, Ruszczak Z, Orfanos CE. Cytokine regulation of proliferation and ICAM-1 expression of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98(2):147–53. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12555746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewi BE, Takasaki T, Kurane I. In vitro assessment of human endothelial cell permeability: effects of inflammatory cytokines and dengue virus infection. J Virol Methods. 2004;121(2):171–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewi BE, Takasaki T, Kurane I. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells increase the permeability of dengue virus-infected endothelial cells in association with downregulation of vascular endothelial cadherin. J Gen Virol. 2008;89(Pt 3):642–52. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan S, Singh S, Aggarwal BB. Induction of endothelial cell surface adhesion molecules by tumor necrosis factor is blocked by protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors: role of the nuclear transcription factor NF-kappa B. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27(9):2172–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin AP, Vargas MJ, Wanionek K, Hammond SN, Gordon A, Rocha C, Balmaseda A, Harris E. Phenotyping of peripheral blood mononuclear cells during acute dengue illness demonstrates infection and increased activation of monocytes in severe cases compared to classic dengue fever. Virology. 2008;376(2):429–35. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elherik KE, Khan F, Belch JJ. Differences in endothelial function and vascular reactivity between Scottish and Arabic populations. Scott Med J. 2003;48(3):85–7. doi: 10.1177/003693300304800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann H, Bugany H, Mahner F, Klenk HD, Drenckhahn D, Schnittler HJ. Filovirus-induced endothelial leakage triggered by infected monocytes/macrophages. J Virol. 1996;70(4):2208–14. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2208-2214.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher-Hoch SP, Platt GS, Neild GH, Southee T, Baskerville A, Raymond RT, Lloyd G, Simpson DI. Pathophysiology of shock and hemorrhage in a fulminating viral infection (Ebola) J Infect Dis. 1985;152(5):887–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen ME, Niedbala MJ, Szczepanski A, Carley WW. Cytokine activation of human macro- and microvessel-derived endothelial cells. Blood Cells. 1993;19(2):325–39. discussion 340-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs LS, Lai L, Malik AB. Tumor necrosis factor enhances the neutrophil-dependent increase in endothelial permeability. J Cell Physiol. 1990;145(3):496–500. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041450315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead SB. Pathogenesis of dengue: challenges to molecular biology. Science. 1988;239(4839):476–81. doi: 10.1126/science.3277268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead SB. Antibody, macrophages, dengue virus infection, shock, and hemorrhage: a pathogenetic cascade. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(Suppl 4):S830–9. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_4.s830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YH, Lei HY, Liu HS, Lin YS, Liu CC, Yeh TM. Dengue virus infects human endothelial cells and induces IL-6 and IL-8 production. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63(1-2):71–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.63.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyngkaran N, Yadav M, Sinniah M. Augmented inflammatory cytokines in primary dengue infection progressing to shock. Singapore Med J. 1995;36(2):218–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M, Levin M. An improved endothelial barrier model to investigate dengue haemorrhagic fever. J Virol Methods. 2002;104(2):173–85. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanlaya R, Pattanakitsakul SN, Sinchaikul S, Chen ST, Thongboonkerd V. Alterations in actin cytoskeletal assembly and junctional protein complexes in human endothelial cells induced by dengue virus infection and mimicry of leukocyte transendothelial migration. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(5):2551–62. doi: 10.1021/pr900060g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JF, Kaufusi PH, Volper EM, Nerurkar VR. Maturation of dengue virus nonstructural protein 4B in monocytes enhances production of dengue hemorrhagic fever-associated chemokines and cytokines. Virology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khongphatthanayothin A, Phumaphuti P, Thongchaiprasit K, Poovorawan Y. Serum levels of sICAM-1 and sE-selectin in patients with dengue virus infection. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2006;59(3):186–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koraka P, Murgue B, Deparis X, Van Gorp EC, Setiati TE, Osterhaus AD, Groen J. Elevation of soluble VCAM-1 plasma levels in children with acute dengue virus infection of varying severity. J Med Virol. 2004;72(3):445–50. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno G, Bailey RE. Cytokine responses to dengue infection among Puerto Rican patients. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1994;89(2):179–82. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761994000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurane I. Dengue hemorrhagic fever with special emphasis on immunopathogenesis. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;30(5-6):329–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurane I, Rothman AL, Livingston PG, Green S, Gagnon SJ, Janus J, Innis BL, Nimmannitya S, Nisalak A, Ennis FA. Immunopathologic mechanisms of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome. Arch Virol Suppl. 1994;9:59–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9326-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurane I, Takasaki T. Dengue fever and dengue haemorrhagic fever: challenges of controlling an enemy still at large. Rev Med Virol. 2001;11(5):301–11. doi: 10.1002/rmv.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth CR, White LJ, Johnston RE, de Silva AM. Flow cytometry-based assay for titrating dengue virus. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(7):3267–72. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3267-3272.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YR, Liu MT, Lei HY, Liu CC, Wu JM, Tung YC, Lin YS, Yeh TM, Chen SH, Liu HS. MCP-1, a highly expressed chemokine in dengue haemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome patients, may cause permeability change, possibly through reduced tight junctions of vascular endothelium cells. J Gen Virol. 2006;87(Pt 12):3623–30. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefer AM. Significance of lipid mediators in shock states. Circ Shock. 1989;27(1):3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong AS, Wong KT, Leong TY, Tan PH, Wannakrairot P. The pathology of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2007;24(4):227–36. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libraty DH, Endy TP, Houng HS, Green S, Kalayanarooj S, Suntayakorn S, Chansiriwongs W, Vaughn DW, Nisalak A, Ennis FA, Rothman AL. Differing influences of virus burden and immune activation on disease severity in secondary dengue-3 virus infections. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(9):1213–21. doi: 10.1086/340365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhtala N, Parker R. LSM1 over-expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae depletes U6 snRNA levels. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(16):5529–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malavige GN, Fernando S, Fernando DJ, Seneviratne SL. Dengue viral infections. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(948):588–601. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.019638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus BC, Wyble CW, Hynes KL, Gewertz BL. Cytokine-induced increases in endothelial permeability occur after adhesion molecule expression. Surgery. 1996;120(2):411–6. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80317-5. discussion 416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medin CL, Fitzgerald KA, Rothman AL. Dengue virus nonstructural protein NS5 induces interleukin-8 transcription and secretion. J Virol. 2005;79(17):11053–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11053-11061.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molet S, Gosset P, Vanhee D, Tillie-Leblond I, Wallaert B, Capron M, Tonnel AB. Modulation of cell adhesion molecules on human endothelial cells by eosinophil-derived mediators. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63(3):351–8. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgue B. Severe dengue: questioning the paradigm. Microbes Infect. 12(2):113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TH, Lei HY, Nguyen TL, Lin YS, Huang KJ, Le BL, Lin CF, Yeh TM, Do QH, Vu TQ, Chen LC, Huang JH, Lam TM, Liu CC, Halstead SB. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in infants: a study of clinical and cytokine profiles. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(2):221–32. doi: 10.1086/380762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooteboom A, Hendriks T, Otteholler I, van der Linden CJ. Permeability characteristics of human endothelial monolayers seeded on different extracellular matrix proteins. Mediators Inflamm. 2000;9(5):235–41. doi: 10.1080/09629350020025755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petreaca ML, Yao M, Liu Y, Defea K, Martins-Green M. Transactivation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 by interleukin-8 (IL-8/CXCL8) is required for IL-8/CXCL8-induced endothelial permeability. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(12):5014–23. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pober JS, Cotran RS. Cytokines and endothelial cell biology. Physiol Rev. 1990;70(2):427–51. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyadarshini D, Gadia RR, Tripathy A, Gurukumar KR, Bhagat A, Patwardhan S, Mokashi N, Vaidya D, Shah PS, Cecilia D. Clinical findings and pro-inflammatory cytokines in dengue patients in Western India: a facility-based study. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1):e8709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghupathy R, Chaturvedi UC, Al-Sayer H, Elbishbishi EA, Agarwal R, Nagar R, Kapoor S, Misra A, Mathur A, Nusrat H, Azizieh F, Khan MA, Mustafa AS. Elevated levels of IL-8 in dengue hemorrhagic fever. J Med Virol. 1998;56(3):280–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199811)56:3<280::aid-jmv18>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahaphong S, Riengrojpitak S, Bhamarapravati N, Chirachariyavej T. Electron microscopic study of the vascular endothelial cell in dengue hemorrhagic fever. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1980;11(2):194–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvaggio MR, Baddley JW. Other viral bioweapons: Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fever. Dermatol Clin. 2004;22(3):291–302. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shresta S, Sharar KL, Prigozhin DM, Snider HM, Beatty PR, Harris E. Critical roles for both STAT1-dependent and STAT1-independent pathways in the control of primary dengue virus infection in mice. J Immunol. 2005;175(6):3946–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srichaikul T, Nimmannitya S. Haematology in dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2000;13(2):261–76. doi: 10.1053/beha.2000.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikiatkhachorn A. Plasma leakage in dengue haemorrhagic fever. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102(6):1042–9. doi: 10.1160/TH09-03-0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]