Abstract

Although both MHC class II/CD8α double knock out and CD8β null mice show a defect in the development of MHC class I-restricted CD8+ T cells in the thymus, they possess low numbers of high avidity peripheral CTL with limited clonality and are able to contain acute and chronic infections. This in vivo data suggests that the CD8 coreceptor is not absolutely necessary for the generation of antigen-specific CTL. Lack of CD8 association causes partial TCR signaling because of the absence of CD8/Lck recruitment to the proximity of the MHC/TCR complex resulting in suboptimal MAPK activation. Therefore, there should exist a signaling mechanism that can supplement partial TCR activation caused by the lack of CD8 association. In this human study, we have shown that CD8-independent stimulation of antigen-specific CTL previously primed in the presence of CD8 coligation, either in vivo or in vitro, induced severely impaired in vitro proliferation. When naïve CD8+ T cells were primed in the absence of CD8 binding and subsequently restimulated in the presence of CD8 coligation, the proliferation of antigen-specific CTL was also severely hampered. However, when CD8-independent T-cell priming and restimulation was supplemented with IL-21, antigen-specific CD8+ CTL expanded in 2 out of 6 individuals tested. We found that IL-21 rescued partial MAPK activation in a STAT3- but not STAT1-dependent manner. These results suggest that CD8 coligation is critical for the expansion of post-thymic peripheral antigen-specific CTL in humans. However, STAT3-mediated IL-21 signaling can supplement partial TCR signaling caused by the lack of CD8 association.

Introduction

The coreceptor CD8 molecule is part of the antigen recognition complex on CD8+ CTL and plays a critical role in CD8+ T cell selection in the thymus (1). CD8 coligation is crucial in the productive activation of MHC class I-restricted antigen-specific CD8+ CTL. Many studies have demonstrated that CD8 molecules improve the efficiency of antigen recognition by CD8+ CTL by enhancing extracellular interactions between MHC/peptide (pMHC) and T cell receptor (TCR) and by promoting the intracellular signaling cascade following TCR engagement (2–5).

However, whether CD8 is absolutely required for the development and activation of CTL has been under discussion. It has been clearly demonstrated that high affinity pMHC/TCR interactions can overcome a lack of CD8 coreceptor binding for full activation of naïve T cells in mice (6–8). Sewell’s group reported that CD8 coreceptor dependence is inversely correlated to pMHC/TCR affinity (9). Furthermore, several groups have demonstrated that CTL with high functional avidity can be selectively identified by MHC/peptide multimers that do not bind CD8 molecules (10–12). These in vitro results indicate that high affinity CTL may not require CD8 coreceptor engagement for their full activation.

CD8 molecules may also not be absolutely required in vivo. While CD8α knockout (KO) mice have a strong bias towards CD4+ T cells and have difficulties inducing CTL responses, these mice were able to contain acute and chronic viral infections (13–15). In MHC class II−/− deficient CD8α−/− double KO mice, peripheral double negative CTL were fully functional, producing protective CTL responses upon acute viral infection (16). CD8β KO mice have 3- to 5-fold lower numbers of mature CD8αα T cells in the periphery and yet, they mount normal primary cytotoxic CD8 responses upon acute viral infection (17, 18). Furthermore, they are able to generate potent secondary and memory CD8+ T cells responses. Importantly, in both MHC class II−/− deficient CD8α−/− double KO mice and CD8β KO mice, peripheral CTL were largely CD8-independent and highly avid (13, 16, 17). In humans, a homozygous missense mutation in the CD8α gene has been reported in a family with three affected members (19). All three individuals had a total absence of CD8+ T cells and an increase in circulating CD4− CD8− T cells with a CTL phenotype. Despite this, only one, a 25 year-old man, suffered from non-severe repeated respiratory bacterial infections, and his two sisters were entirely asymptomatic. These in vivo observations demonstrate that it is possible to develop CTL responses in the absence of the CD8 coreceptor that are qualitatively sufficient to target antigens.

The significance of common γ chain receptor cytokines (e.g. IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21) in T cell biology has been well established (20, 21). All these cytokines transmit STAT-mediated signaling via the common γ chain receptor in T cells (22, 23). Importantly, it has been demonstrated that cross-talk between TCR and STAT signaling occurs in CD8+ T cells (24, 25). For example, partial or weak TCR-initiated signaling via the Ras/MAPK pathway can be complemented by IL-2 induced STAT activation (25, 26). This mechanism enables adaptive cytokines to supplement suboptimal TCR signaling or to modulate optimal TCR signaling. Importantly, even though these cytokines bind to and signal through the common γ chain receptor to support T cell proliferation and differentiation, each cytokine has a distinctive role in T cell growth, lineage control/determination, differentiation, function, and death (20–23). Previously, we and others have shown that both IL-15 and IL-21 can enhance CTL effector functions and induce the proliferation and maturation of CTL with high TCR avidity (27–30).

Based on these observations, we have hypothesized that CD8 coreceptor-independent T cell stimulation in the presence of complementary adaptive cytokines will preferentially stimulate high avidity antigen-specific CTL. In order to investigate the role of CD8 binding during T cell stimulation, previous studies, to the best of our knowledge, invariably utilized T cell clones or TCR transgenic T cells that had been isolated after originally being primed in vivo in the presence of full CD8 coligation. Therefore, it has yet to be determined how the lack of CD8 engagement during priming and/or subsequent restimulation will affect the generation of antigen-specific CTL. Previously, we reported the generation of K562-based artificial APC (aAPC) by transducing HLA-A2, CD80, and CD83 (28, 31). This aAPC can prime naïve CD8+ T cells in vitro and generate high avidity antigen-specific CD8+ CTL with a central memory~effector memory phenotype (28). Using our aAPC-based system, we have addressed this hypothesis.

Materials and Methods

Cells

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from healthy donors following institutional review board approval. All donors were identified to be positive for HLA-A*0201 (A2) by high resolution HLA DNA typing (American Red Cross). Mononuclear cells were obtained by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep; Nycomed Pharma). CD8+ T cells were purified by CD8 Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec).

K562 is an erythroleukemic cell line defective for HLA expression. T2 is an HLA-A2 positive T cell leukemia/B-LCL hybrid. Jurkat is a T cell leukemic cell line. J.CaM1.6 is a Jurkat mutant, which lacks the expression of Lck. All cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and gentamycin (Invitrogen).

Transfectants

CD8α and CD8β cDNAs were cloned by RT-PCR from total RNA isolated from normal PBMC according to the published sequence. Sequences were verified by the Molecular Biology Core at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. K562 was transduced with CD8α to establish K562/CD8αα using a retrovirus system as reported previously (31). Briefly, a packaging cell line, 293GPG, was transfected with pMX/CD8α retrovirus vector using TransIT-293 (Takara Bio) and virus supernatant was harvested. One million K562 cells were infected with the virus supernatant in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene. CD8α positive K562/CD8αα cells were collected using biotin-conjugated anti-CD8α mAb and anti-biotin beads according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Miltenyi Biotec). K562/CD8αα cells were further retrovirally transduced with CD8β to generate K562/CD8αβ. K562/CD8αβ cells were purified using biotin-conjugated anti-CD8β mAb and anti-biotin beads as described above. Mutated HLA-A2 cDNA bearing two amino acid substitutions at positions 227 and 228 (D227K/T228A) that abrogate the interaction with A2 was reported previously (4). The generation of aAPC expressing HLA-A2, CD80 and CD83 and its derivative, which constitutively secretes IL-21, was reported previously (27, 31). Mut-aAPC secreting IL-21 express mutated HLA-A2 in lieu of wild-type A2 and were generated similarly using a retrovirus system. Wt- and mut-aAPC secreting IL-21 secreted similar amounts of IL-21 (0.33 ± 0.06 and 0.25 ± 0.07 μg/ml, respectively) per 106 cells over 24 hr. The cell line, mOKT3-aAPC, expresses a membranous form of anti-CD3 mAb (Clone OKT3), CD80, and CD83 on K562 to allow polyclonal expansion of CD3+ T cells regardless of antigen specificity and HLA restriction (submitted for publication by Butler et al.). cDNAs encoding a membranous form of the heavy and light chains of anti-CD3 mAb were molecularly cloned from mouse hybridoma cells (clone OKT3). After retroviral transduction with drug resistance genes and subsequent drug selection, anti-CD3 mAb expressing cells were isolated by magnetic bead guided sorting using PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig polyclonal Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and anti-PE MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec). J.CaM1.6 is a Jurkat mutant, which lacks the expression of Lck. Jukat/IL-21R and J.CaM1.6/IL-21R were retrovirally generated as described elsewhere (27).

HLA/peptide multimer staining

Wild type HLA-A2 and mutated A2/peptide multimers were produced and utilized to stain cells as described previously (31, 32).

Flow cytometry analysis

PE- and PC5-conjugated anti-CD8α (Clone B9.11) and anti-CD8β (Clone 2ST8.5H7) mAbs were purchased from Beckman Coulter and used to stain CD8αα homodimers and CD8αβ heterodimers, respectively.

To determine the phenotype of MART127-specific T cells, T cells were first stained with HLA-A2/peptide multimers as previously described (31, 32). Multimer-positive T cells were costained with the following mAbs: FITC-conjugated anti-CCR7 (Clone 150503, R&D Systems), TC-conjugated anti-CD45RA (Clone MEM-56, Invitrogen), TC-conjugated anti-CD45RO (Clone UCHL1, Invitrogen), and PC5-conjugated anti-CD62L (Clone DREG56, Beckman Coulter) mAbs.

Cell surface molecules on transfectants were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-A2 (Clone BB7.2, BD Biosciences), PE-conjugated anti-CD80 (Clone L307.4, BD Biosciences), PE-conjugated anti-CD83 (Clone HB15e, Invitrogen). IL-21R was indirectly stained with anti-IL-21R (Clone 152512, R&D Systems) mAb and PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig polyclonal Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Intracellular phosphorylated MAPK, STAT1, and STAT3 were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204, clone E10, Cell Signaling Technology), PE-conjugated anti-phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701, clone 4a, BD Biosciences), and PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705, clone 4/P-STAT3, BD Biosciences) mAbs, respectively, as published elsewhere (33). Briefly, resting or stimulated T cells were fixed with 1.5% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 100% methanol at 4°C and stained with mAb for 30 min at room temperature.

Stained cells were analyzed with a Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) using FlowJo (TreeStar) software as published previously (27, 28, 34).

Production of HLA-A*0201-restricted peptide-specific CD8+ T cells

Peptide-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells were generated using aAPC as described previously (27, 28, 31, 34, 35). Briefly, purified CD8+ lymphocytes were plated at 2 × 106 cells/well in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% human AB serum. The stimulator aAPC was pulsed with 0.1 μg/ml MP158 peptide (58GILGFVFTL66) from the MP1 antigen of influenza virus or 10 μg/ml MART127 peptide (27AAGIGILTV35) of the tumor antigen MART1 (New England Peptide) for 6 hours at room temperature (35). The aAPC was then irradiated at 200 Gy, washed, and added to the responder T cells at a responder to stimulator ratio of 20:1. Starting the next day, 10 IU/ml IL-2 (Novartis) and 10 ng/ml IL-15 (Peprotech) were added to the cultures every three days. T cells were harvested, counted, and restimulated every week. T cell analysis was performed one day prior to or on the day of restimulation. HLA-A2-restricted HIV pol476 peptide (476ILKEPVHGV484) was used as a control.

Cell division tracing assay

CellTrace Violet (Invitrogen) was added to one million T cells in 1 ml serum-free media at a final concentration of 5 μM and incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C. Labeled cells were stimulated with wt or mut-aAPC pulsed with MP158 or MART127 peptide as described above. Three to five days later, stimulated T cells were stained with PE-conjugated multimer and PC5-conjugated anti-CD8α and analyzed by flow cytometry.

ELISPOT analysis

IFN-γ ELISPOT assay was conducted as described elsewhere (27, 28, 31, 34, 35). Briefly, PVDF plates (Millipore) were coated with capture mAb (Clone 1D1K; MABTECH). T cells (1 × 104 per well) were incubated with 2 × 104 per well of indicated APC in the presence of peptide for 20–24 hours at 37°C. Plates were washed and incubated with biotin-conjugated detection mAb (Clone 7-B6-1; MABTECH). HRP-conjugated streptavidin was used to develop IFN-γ spots. Functional avidity was tested using T2 cells pulsed with graded concentrations of MART127 peptide as stimulators in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. Where indicated, mOKT3-aAPC (2 × 104 per well) or a combination of 1.5 μg/ml anti-CD3 and 2 μg/ml anti-CD28 mAbs (Fitzgerald Industries International) was used as a stimulator in the absence or presence of recombinant 100 ng/ml IL-21 (Peprotech). To inhibit STAT1, STAT3, and MAPK, graded concentrations of fludarabine (Sigma-Aldrich), S3I-201 (Merck4Biosciences), and/or PD98059 (Merck4Biosciences), respectively, were added to the cultures as indicated.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity assay was conducted as described previously (28, 31). Briefly, 5 × 103 T2 cells pulsed with graded concentrations of MART127 peptide were mixed with 5 × 104 MART1 CTL for 4 hours at 37°C in a 96 well round bottom plate. Percent specific lysis was calculated [(experimental result - spontaneous release)/(maximum release - spontaneous release)] × 100%.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2004/2008 for Mac and GraphPad Prism 5.0d. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant. To determine whether two groups were statistically different for a given variable, analysis was performed using the Student t test (two-sided) or by a repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons test.

Results

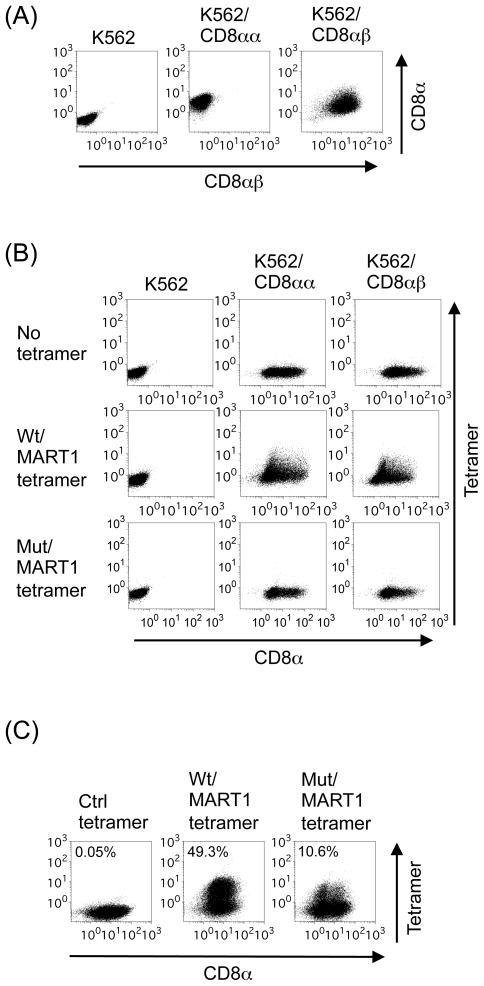

Mutated A2 molecules cannot bind either CD8αα or CD8αβ

Most peripheral CD8+ TCRαβ T cells carry CD8αβ heterodimers on their cell surface. In contrast, CD8αα homodimers are found only on NK cells, TCRγδ T cells, and intraepithelial lymphocytes (36). While CD8αα homodimers bind directly to MHC molecules, CD8ββ homodimers do not have detectable MHC-binding activity. However, CD8β chain possesses amino acids in its Ig domain that directly contact MHC class I molecules in the context of CD8αβ heterodimers, thereby strengthening the binding of MHC/peptide to TCR (37–39). It has been reported that mutated HLA-A2 (mut A2) molecules carrying 2 amino acid substitutions (D227K/T228A) does not bind CD8αα homodimers (4, 40). To test whether mut A2 is also unable to bind CD8αβ heterodimers, K562 were transduced with CD8α alone or in conjunction with CD8β to establish K562/CD8αα and K562/CD8αβ, respectively (Figure 1A). K562/CD8αα and K562/CD8αβ were incubated with wild-type (wt) HLA-A2/MART1 tetramer or mut A2/MART1 tetramer. Unlike wt A2 tetramer, mut A2 tetramer was unable to bind both K562/CD8αα and K562/CD8αβ (Figure 1B). These results suggest that mut A2 molecules (D227K/T228A) cannot bind either CD8αα or CD8αβ.

Figure 1. HLA-A2 molecules with impaired CD8 binding ability are incapable of binding CD8αα and CD8αβ.

(A) K562 can ectopically express CD8αα homodimers and CD8αβ heterodimers on the cell surface. K562 was retrovirally transduced with CD8α (K562/CD8αα) and subsequently with CD8β (K562/CD8αβ). Transfectants were stained with anti-CD8α and anti-CD8β mAbs and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. Similar experiments were repeated 3 times. (B) K562/CD8αα and K562/CD8αβ were incubated with CD8α mAb and with wild type (wt) or mutant (mut) A2/MART127 tetramers in which CD8 binding is abolished. Similar experiments were repeated 3 times. (C) Established HLA-A2 restricted MART127-specific CTL were stained with wt or mut tetramers and subsequently with anti-CD8α mAb. Representative tetramer staining data of one CTL line out of 9 is shown.

Previously, we reported the generation of K562-derived HLA-A2 artificial APC (wt A2-aAPC), which expresses wt HLA-A2 as a sole HLA allele in conjunction with CD80 and CD83 (31). Wt A2-aAPC can prime naïve CD8+ T cells isolated from HLA-A2+ donors and expand highly avid HLA-A2-restricted antigen-specific CTL with a central~effector memory phenotype (28, 34, 35). Several groups have reported that CTL with high functional avidity can be selectively identified with mut A2 tetramers (10–12, 41). When MART127-specific CTL generated using wt A2-aAPC were stained with wt and mut A2 tetramers, mut A2 tetramer was able to stain MART1 CTL, although at a lower percentage than wt A2 tetramer (Figure 1C). These results suggest that mut A2/peptide molecules can recognize cognate TCR expressed on a subpopulation of CTL, possibly with high avidity, in the absence of CD8 association.

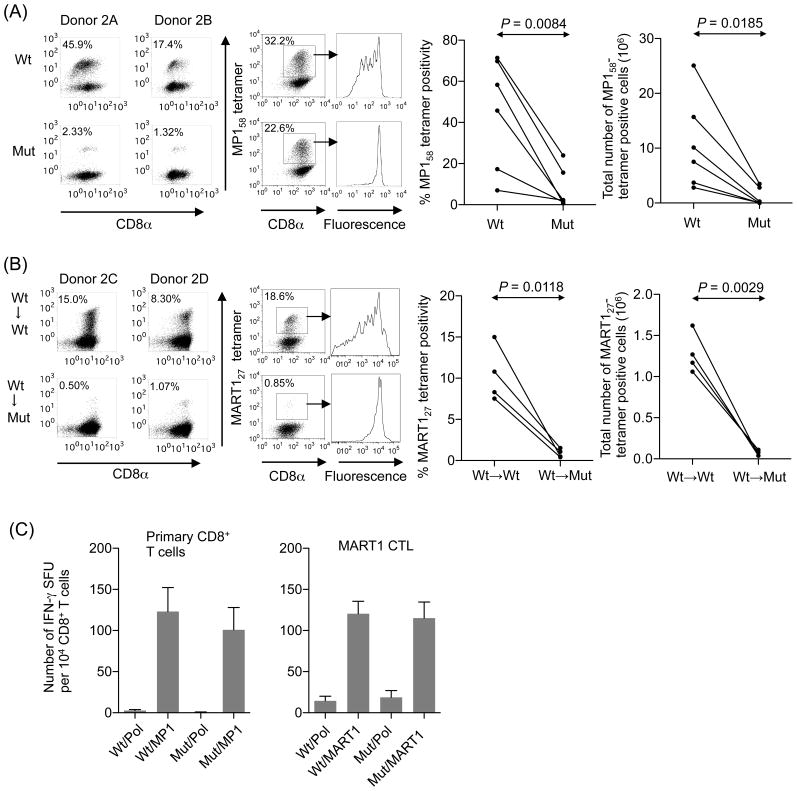

CD8-independent TCR engagement is defective in inducing the proliferation of antigen-specific CTL previously primed in the presence of CD8 engagement

We have replaced wt A2 molecules on A2-aAPC with mut A2 molecules to generate mut A2-aAPC (Supplementary Figure 1). Using wt and mut A2-aAPC, we investigated the requirement of the CD8 coreceptor association for the expansion of antigen-specific human CD8+ T cells. Most HLA-A2+ healthy donors possess memory CTL against MP158 that have been primed in vivo in the presence of CD8 coligation. CD8+ T cells freshly purified from A2+ donors were stimulated once a week using wt or mut-aAPC pulsed with MP158 peptide. After three stimulations, antigen specificity was measured by tetramer staining. The percentage of MP158 specific T cells was significantly lower for CTL stimulated with mut-aAPC compared to wt-aAPC (Figure 2A, left). Cell division tracing assay revealed that MP158-specific CTL stimulated with mut-aAPC did not proliferate as robustly as those stimulated with wt-aAPC (Figure 2A, center). Accordingly, the total number of generated MP158-specific CTL was significantly lower after stimulation with mut-aAPC compared to wt-aAPC (Figure 2A, right).

Figure 2. CD8-independent TCR stimulation is defective in inducing proliferation of antigen-specific CTL previously primed in the presence of CD8 engagement.

(A) In vivo primed MP158-specific CTL expand significantly less when stimulated in vitro in the absence of CD8 coligation. CD8+ T cells freshly isolated from six A2+ healthy donors were stimulated with wt or mut-aAPC pulsed with 0.1 μg/ml MP158 peptide every week. IL-2 (10 IU/ml) and IL-15 (10 ng/ml) were added to the cultures every three days. After 3 stimulations, expanded MP158- specific CTL were stained with wt tetramers to determine the antigen-specificity. Representative tetramer staining data from two out of six donors is shown (left). Expanded T cells were also stained with CellTrace Violet and stimulated with wt- or mut-aAPC pulsed with MP158 peptide. The dilution of CellTrace Violet as an indicator of cell division was assessed on MP158-specific CTL in conjunction with multimer staining (center). Data is representative of 6 donors. The number of peptide-specific T cells was determined by calculating the product of the total number of T cells and the percentage of tetramer-staining cells (right). The percentage tetramer positivity and the total number of MP158-specific CD8+ T cells are statistically compared using paired, two-sided Student’s t-tests. (B) In vitro primed MART127-specific CTL expand significantly less when stimulated in vitro in the absence of CD8 coligation. Purified naïve CD8+ T cells from four A2+ healthy donors were initially primed in the presence of CD8 coengagement using wt-aAPC pulsed with 10 μg/ml MART127 peptide for priming. Subsequently, primed CD8+ T cell cultures were split in half and restimulated three times with either wt- or mut-aAPC pulsed with 10 μg/ml MART127 once a week. Between stimulations, IL-2 (10 IU/ml) and IL-15 (10 ng/ml) were added to the cultures every 3 days. After 3 restimulations, expanded MART127-specific CTL were stained with wt tetramers to determine the antigen-specificity. Representative tetramer staining data from two donors out of 4 is shown. Cell division of MART127-specific CTL was determined as described in Figure 2A(center). Data is representative of 6 donors. The percentage tetramer positivity and the total number (right) of MART127-specific CD8+ T cells are statistically compared using paired, two-sided Student’s t-tests. (C) Wt and mut-aAPC can present pulsed A2-restricted peptides with a similar efficiency. IFN-γ ELISPOT was conducted where CD8+ T cells freshly isolated from A2+ healthy donors were stimulated using wt or mut-aAPC pulsed with 0.1 μg/ml MP158 peptide. Established MART127-specific CTL were also subjected to IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis using wt or mut-aAPC pulsed with 10 μg/ml MART127 peptide as a stimulator. The peptide concentrations used are the same as those used in Figures 2A and 2B. For each peptide, similar results were obtained from 3 different donors. Representative data for each peptide is demonstrated. Error bars show S.D.

Previously, we and others demonstrated that MART127-specific CD8+ precursor cells in HLA-A2+ healthy donors are immunologically and phenotypically naïve (31, 42, 43). Naïve CD8+ T cells isolated from A2+ healthy donors were initially primed with MART127 peptide-pulsed wt-aAPC in the presence of CD8 coligation. Primed CD8+ T cells were split and subsequently restimulated 3 times using either MART127 peptide-pulsed wt- or mut-aAPC. The percentage of MART127 tetramer positive CTL was significantly lower after restimulation with mut-aAPC compared to wt-aAPC (Figure 2B, left). As was the case with MP158-specific CTL, MART127-specific CTL showed poorer proliferation after stimulation with mut-aAPC compared to wt-aAPC (Figure 2B, center). Again, the total number of expanded MART127-specific CTL was significantly lower when mut-aAPC was used as a stimulator compared with wt-aAPC (Figure 2B, right). Taken all together, these results demonstrate that CD8-independent T cell restimulation does not efficiently induce proliferation of antigen-specific CTL previously primed, either in vivo or in vitro, in the presence of CD8 coligation.

The threshold for cytokine production is generally lower than that for proliferation (44). Previous studies demonstrated that the A2 molecules with D227K/T228A mutations inhibit the CD8/MHC interaction without affecting the TCR/pMHC interaction (4). To confirm that both wt and mut A2 molecules on our aAPC can indeed engage TCR with similar efficiency, we tested whether MP158-specific memory CTL effector functions induced by wt- and mut-aAPC are comparable. An IFN-γ ELISPOT assay using freshly isolated CD8+ T cells detected similar frequencies of IFN-γ secreting CD8+ T cells when stimulated with MP158 peptide-pulsed wt or mut A2-aAPC (Figure 2C, left). Similar results were obtained with previously established MART127-specific CTL (Figure 2C, right). These results suggest that, under the experimental conditions tested, both wt and mut A2 molecules on our aAPC are able to engage cognate TCR with similar efficiency.

Priming in the absence of CD8 coligation is defective in inducing the subsequent expansion of antigen-specific CTL upon restimulation

To study whether priming in the absence of CD8 coengagement is sufficient to enable subsequent antigen-specific proliferation upon restimulation, naïve CD8+ T cells isolated from A2+ healthy donors were split into three populations and primed with either mut-aAPC pulsed with either irrelevant HIV pol476 or MART127 peptide or with wt-aAPC pulsed with MART127 peptide. Following priming, these three CD8+ T cell cultures were all restimulated three times in a weekly manner with MART127 peptide-pulsed wt-aAPC in the presence of CD8 coligation. The percentage of MART127 tetramer positive CTL was significantly lower after priming with MART127-pulsed mut-aAPC compared to MART1-pulsed wt-aAPC in all individuals tested (Figure 3). Furthermore, the total number of generated MART127-specific CTL was also significantly lower when mut-aAPC was used compared with wt-aAPC (data not shown). Importantly, CD8-independent priming with mut-aAPC pulsed with MART127 or HIV pol476 was both significantly inferior in subsequent expansion of MART1-specific CTL. This suggests that, priming in the absence of CD8 signaling does not induce a sufficient survival or stimulatory signal for naïve CD8+ T cells to subsequently proliferate as antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

Figure 3. CD8-independent TCR stimulation is defective in priming naïve T cells and the proliferation of antigen-specific CTL.

Naïve CD8+ CTL cannot be primed in the absence of CD8 coligation. Purified naïve CD8+ T cells from six healthy donors were initially stimulated with one of three aAPC; mut-aAPC pulsed with 10 μg/ml HIV pol476 or MART127 peptide or with wt-aAPC pulsed with MART127 peptide. Following this attempted priming, all CD8+ T cell cultures were repeatedly restimulated with wt-aAPC pulsed with 10 μg/ml MART127 in a weekly manner. Between stimulations, the CTL cultures were given 10 IU/ml IL-2 and 10 ng/ml IL-15 every three days. After a total of 4 stimulations, MART127 specificity of generated CTL was analyzed by wt tetramer staining. Representative tetramer staining data from three donors out of six are depicted (left). The percentage tetramer positivity of MART127-specific CD8+ T cells from all six donors is statistically compared (right). Note that data points, which are shown for all 6 donors, partially overlap. Statistics were determined by repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparison test.

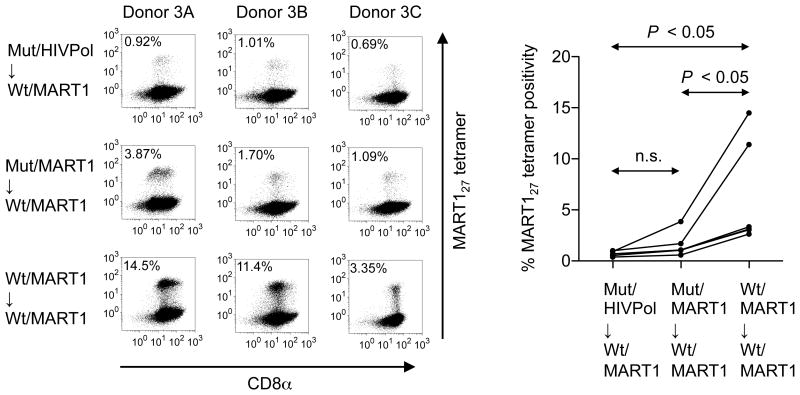

IL-21 can supplement suboptimal CD8-independent TCR stimulation

The data presented in Figure 2 demonstrates that CD8-independent restimulation is defective in expanding antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. We show in Figure 3 that priming of naïve CD8+ T cells in the absence of CD8+ coengagement is insufficient to induce the full expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells upon subsequent restimulation. These results strongly suggest that, if naïve CD8+ T cells are primed and subsequently restimulated in the complete absence of CD8 coligation, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells do not grow. To confirm this, naïve CD8+ T cells purified from healthy A2+ donors were both primed and restimulated with either wt- or mut-aAPC pulsed with MART127 peptide. Between stimulations, the cells were treated with IL-2 and IL-15. As shown in Figure 4A, priming and restimulation with MART127 peptide-pulsed mut-aAPC in the total absence of CD8 coligation failed to induce an expansion of MART127-specific CTL. In contrast, CTL stimulated with MART127 peptide-pulsed wt-aAPC in the presence of CD8 engagement successfully generated MART127-specific CTL. It should be noted that, in our laboratory, we have successfully generated MART127-specific CTL using wt-aAPC from greater than 100 A2+ healthy donors without any failure under the experimental conditions employed (27, 28, 31, 34, 35). These results clearly demonstrate that priming and subsequent restimulation of naïve CD8+ T cells in the complete absence of CD8 coligation cannot expand MART127-specific CTL.

Figure 4. IL-21 can rectify defective CD8-independent TCR stimulation.

(A) MART127-specific CTL cannot expand when primed and restimulated in the complete absence of CD8 coligation. Naïve CD8+ T cells freshly isolated from six healthy donors were primed and restimulated by either wt or mut-aAPC pulsed with 10 μg/ml MART127 peptide. Between stimulations, the CTL cultures were given 10 IU/ml IL-2 and 10 ng/ml IL-15 every three days. After 4 stimulations, MART127 specificity was analyzed by wt tetramer staining. The percentage of tetramer positive MART127-specific CD8+ T cells and the total number of MART127-tetramer positive cells after stimulation with wt- and mut-aAPC are shown (Figures 4A, right). Four representative plots of six similar experiments are shown. Note that data points, which are shown for all 4 donors, partially overlap (Donors 4A and 4C). (B) IL-21 enables the proliferation of antigen-specific CTL primed and restimulated in the absence of CD8 coengagement. MART127-specific CTL were generated as described in Figure 3A except that IL-21 secreting wt and mut-aAPC were used as stimulators. When parental mut-aAPC, which does not secrete IL-21, was used as a stimulator as described in Figure 3A, there was no growth of MART127-specific CTL (data not shown). Data for three out of six donors are shown. The percentage of tetramer positive MART127-specific CD8+ T cells and the total number of MART127-tetramer positive cells after stimulation with IL-21 secreting wt- and mut-aAPC are shown (Figures 4B, right). (C) MART127-specific CTL primed and restimulated in the absence of CD8 coligation possess higher functional avidity. The avidity of MART127-specific CTL generated using wt and mut-aAPC secreting IL-21 was compared using T2 cells pulsed with graded concentrations of MART127 peptide in an IFN-γ ELISPOT. Functional avidity, expressed as MC50 in μg/ml, was defined as the concentration of peptide required to achieve 50% of maximal response. Functional avidities (MC50 values) of MART127-specific CTL stimulated by IL-21-secreting wt-aAPC and mut-aAPC were 2.5 × 10−2μg/ml and 4.0 × 10−3μg/ml, respectively. Representative data from one of 3 donors is shown. (D) The avidity of MART127-specific CTL generated using wt and mut-aAPC secreting IL-21 was compared using T2 cells pulsed with graded concentrations of MART127 peptide in cytotoxicity assay. Functional avidities (MC50 values) of MART127-specific CTL stimulated by IL-21-secreting wt-aAPC and mut-aAPC were 0.7 × 10−4μg/ml and 0.3 × 10−4μg/ml, respectively. Representative result from one of 6 donors is shown.

As shown above, CD8-independent priming and restimulation with mut-aAPC in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15 were unable to expand MART1-specific CD8+ T cells. Since the total loss of CD8 molecules is not lethal in humans, however, a rescue signal should be present that complements partial T cell stimulation caused by the absence of CD8 coligation (19). It has been demonstrated that STAT signaling mediated by common γ chain receptor cytokines can supplement partial or weak TCR signaling (24, 25). Since our T cell cultures already included both IL-2 and IL-15, it was unlikely that IL-2 and/or IL-15 would rescue suboptimal TCR signaling delivered by mut-aAPC. We and others previously reported that IL-21 possesses unique immunologic properties that are not shared by either IL-2 or IL-15 (22, 23, 27, 29). This prompted us to test whether IL-21 was able to supplement the defective CD8-independent TCR signaling in T cells stimulated by mut-aAPC. Purified CD8+ T cells from A2+ donors were stimulated using MART127 peptide-pulsed wt- or mut-aAPC constitutively secreting IL-21. As shown in Figure 4B, CD8-independent priming and restimulation using mut-aAPC producing IL-21 successfully expanded MART127-specific CTL in 2 out of 6 donors studied (donors 4D and 4F). Priming and restimulation using mut-aAPC that does not secrete IL-21 did not expand any MART127-specific CTL at all (Figure 4A and data not shown). Under the experimental conditions employed, we did not observe a decrease in total number of T cells or MART127-specific CTL by the addition of IL-21 to T cell cultures (Figures 4A and B) (27). Furthermore, no consistent difference in surface phenotype was observed between MART127-specific CTL expanded using IL-21 secreting wt- and mut-aAPC (Supplementary Figure 2).

We next compared the functional avidity of the CTL generated using IL-21 secreting wt-and mut-aAPC. An IFN-γ ELISPOT assay demonstrated that the functional avidity of MART127-specific CTL generated by IL-21 secreting mut-aAPC was 4.0 × 10−3μg/ml (MC50), which was higher than that of MART127-specific CTL generated by IL-21 secreting wt-aAPC (2.5 × 10−2 μg/ml) (Figure 4C). We also conducted a Cr51 release assay using MART127-specific CTL generated from a different donor using IL-21 secreting wt- and mut-aAPC. MART127-specific CTL generated using IL-21 secreting mut-aAPC possessed similar or slightly higher functional avidity (3.0 × 10−5μg/ml) than MART127-specific CTL generated using IL-21 secreting wt-aAPC (7.0 × 10−5μg/ml) (Figure 4D). These results suggest that IL-21 signaling can supplement CD8-independent suboptimal T cell stimulation by mut-aAPC and enable the expansion of MART127-specific CTL.

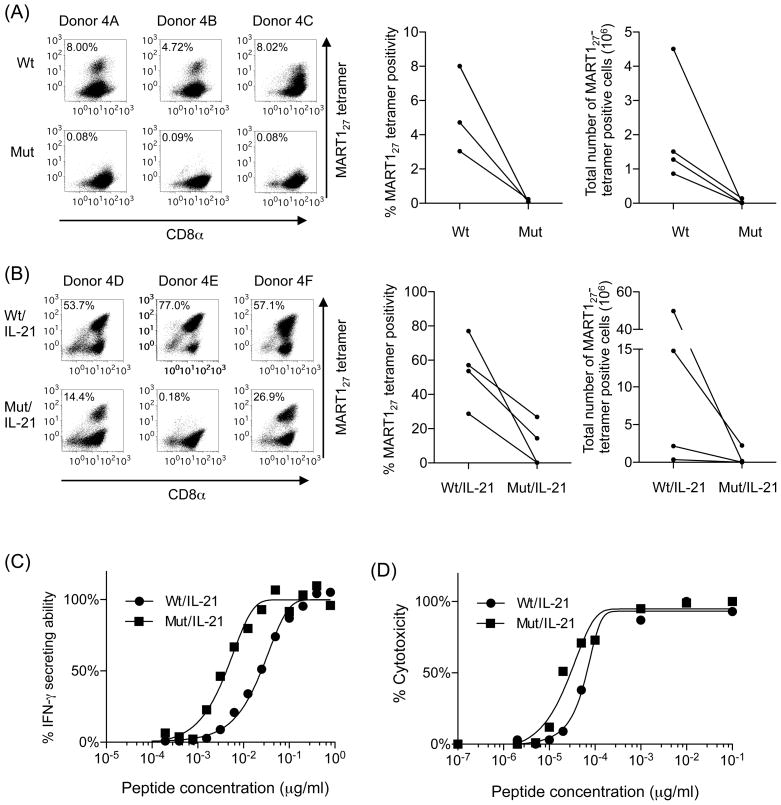

IL-21 can complement suboptimal CD8-independent MAPK signaling in a STAT3-dependent manner

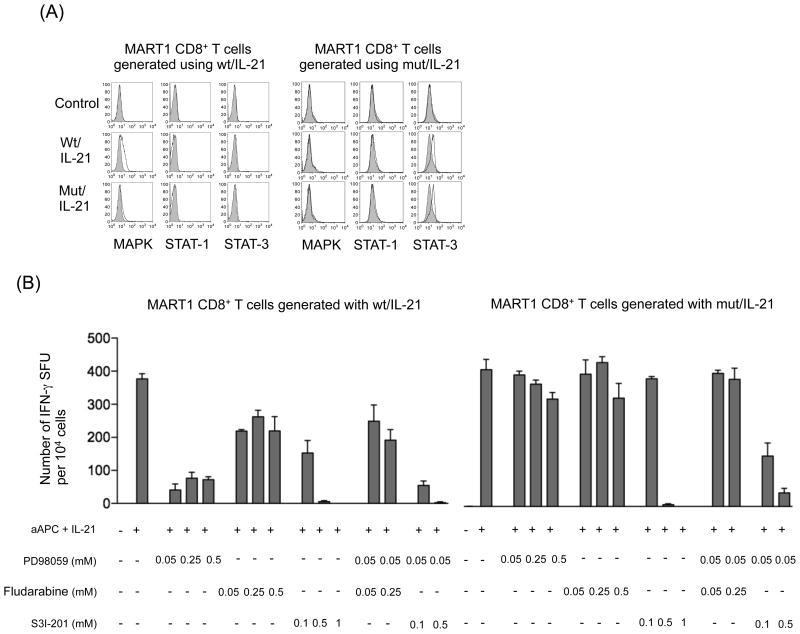

IL-21 delivers its intracellular signal mainly via STAT1 and STAT3 (21). To gain insights into the mechanism of IL-21-mediated rescue of CD8-independent T cell stimulation, we examined phosphorylation of MAPK, STAT1, and STAT3 in MART1-specific CD8+ T cells stimulated by IL-21 secreting wt- and mut-aAPC. When stimulated by IL-21 secreting wt-aAPC, MART127-specific CTL generated with IL-21-secreting wt-aAPC demonstrated some MAPK phosphorylation. IL-21 secreting mut-aAPC induced minimal MAPK phosphorylation of MART127-specific CTL generated with IL-21 secreting wt-aAPC. This suggests that stimulation by mut-aAPC in the absence of CD8 coligation is not sufficient to evoke MAPK phosphorylation, probably because of the lack of Lck activation, which is a downstream event of CD8 coligation (1). Neither STAT1 or STAT3 phosphorylation was observed under the experimental conditions used (Figure 5A, left). In contrast, MART127-specific CTL generated with IL-21 secreting mut-APC demonstrated phosphorylation of STAT3 but not MAPK or STAT1 when stimulated with either IL-21 secreting wt- or mut-aAPC (Figure 5A, right). This suggests that, in MART127-specific CTL generated with IL-21 secreting mut-APC in the absence of CD8 coligation, STAT-3-mediated IL-21 signaling predominates over MAPK-mediated TCR signaling. Note that MART127-specific CTL were stimulated by cell-based aAPC in an antigen-specific manner. Therefore, the observed phosphorylation levels were not very high since the induced stimulations were not maximal and were directed against only the MART1-specific TCR subset.

Figure 5. IL-21 signaling rescues CD8-independent T cell stimulation in a STAT3-dependent manner.

(A) STAT3 but not MAPK became phosphorylated in MART127-specific CTL generated using IL-21 secreting mut-aAPC. MART127-specific CTL generated using IL-21 secreting wt- and mut-aAPC were restimulated with each aAPC and the phosphorylation level of MAPK, STAT1 and STAT3 was determined by intracellular staining using specific mAbs for phosphorylated molecules in a flow cytometry analysis. Unstimulated cells were depicted as control. Isotype mAb staining was used as a control. Representative result from one of 4 donors is shown. (B) IFN-γ secretion by MART127-specific CTL generated using IL-21 secreting mut-aAPC is STAT3-dependent. MART127-specific CTL generated using IL-21 secreting wt- and mut-aAPC were stimulated with each aAPC in the presence of graded concentrations of inhibitors against MAPK (PD98059), STAT1 (Fludarabine) and/or STAT3 (S3I-201). IFN-γ secretion was analyzed by an ELISPOT assay as described in the Materials and Methods. Representative result from one of 4 donors is shown.

Using specific inhibitors in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay, we also studied how IL-21 signaling supplements CD8-independent T cell signaling during the effector phase (Figure 5B). IFN-γ secretion by both MART127-specific CTL lines generated using IL-21 secreting wt- and mut-aAPC was completely abrogated by STAT3 inhibition alone, indicating a critical role of STAT3 in IFN-γ secretion. The inhibition of MAPK alone severely hampered the IFN-γ secretion by MART127-specific CTL lines generated using IL-21 secreting wt-aAPC. While inhibition of MAPK alone had minimal impact on MART127-specific CTL generated using IL-21 secreting mut-aAPC, the effect of STAT3 inhibition was markedly augmented by the coinhibition of MAPK. The effect of STAT1 inhibition was modest, at best, in MART127-specific CTL lines generated using IL-21 secreting wt-aAPC and was not observed in those generated using IL-21 secreting mut-aAPC. These results suggest that IL-21 can complement suboptimal CD8-independent MAPK signaling via a STAT3-dependent manner.

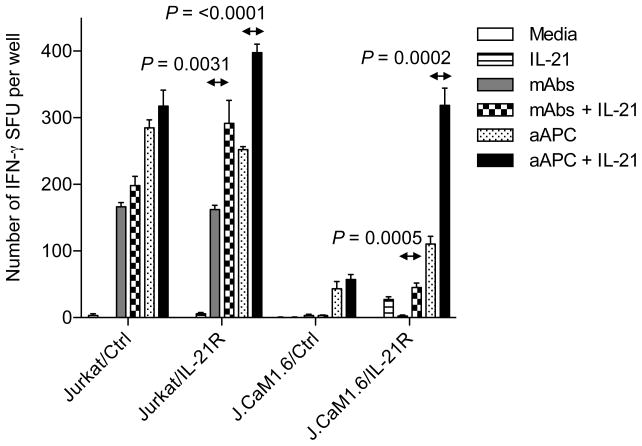

IL-21 can rescue suboptimal T cell stimulation via a STAT3-dependent manner in the absence of Lck, a downstream effector molecule of CD8 coligation

CD8 is associated with the tyrosine kinase, Lck. When CD8 binds pMHC, Lck phosphorylates components of the TCR/CD3 signaling complex and enhance signal transduction (1). Therefore, lack of CD8 binding to pMHC results in partial TCR signaling (4, 45, 46). In fact, Lck KO mice had a profound defect in thymocyte development. Using Jurkat and Jurkat-derived Lck-null J.CaM1.6 cells, we studied whether IL-21-mediated STAT signaling can rescue partial TCR signaling incurred by the absence of Lck. To stimulate Jurkat- and J.CaM1.6-transfectants, we used mOKT3-aAPC, on which HLA-A2 was substituted with a membranous form of anti-CD3 mAb. Jurkat and J.CaM1.6, both devoid of IL-21R expression, were engineered to constitutively express IL-21R (Supplementary Figure 3). When stimulated by mOKT3-aAPC, control Jurkat and J.CaM1.6 minimally responded to IL-21 (Figure 6). However, both IL-21R-transduced Jurkat and J.CaM1.6 demonstrated robust responses to IL-21. Although the magnitude of the responses to IL-21 was less, especially in IL-21R-tranduced J.CaM1.6 cells, similar results were obtained when anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs were used as stimulators. It should be noted that, unlike anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs, mOKT3-aAPC delivers not only signals 1 and 2 but also other signals mediated by immunostimulatory molecules such as CD54, CD58, and CD83 (28, 31). These results suggest that IL-21 can complement suboptimal TCR signaling in the absence of Lck.

Figure 6. IL-21 signaling can rescue partial T cell responses caused by the lack of Lck.

Constitutive expression of IL-21R can enhance IL-21-dependent T cell responses in the absence of Lck. Jurkat cell line (104 cells per well) and its Lck-null derivative, J.CaM1.6 (105 cells per well), stably expressing mock or IL-21R were stimulated with mOKT3-aAPC (aAPC) (2 × 104 per well) or 1.5 μg/ml anti-CD3 and 2 μg/ml anti-CD28 mAbs in the absence or presence of 100 ng/ml recombinant IL-21 in an IFN-γ ELISPOT. aAPC denotes a K562-derived APC expressing a membranous form of anti-CD3 mAb, CD80, and CD83. Unpaired, two-sided Student’s t-test was used for two-sample comparisons. Similar experiments were repeated 3 times.

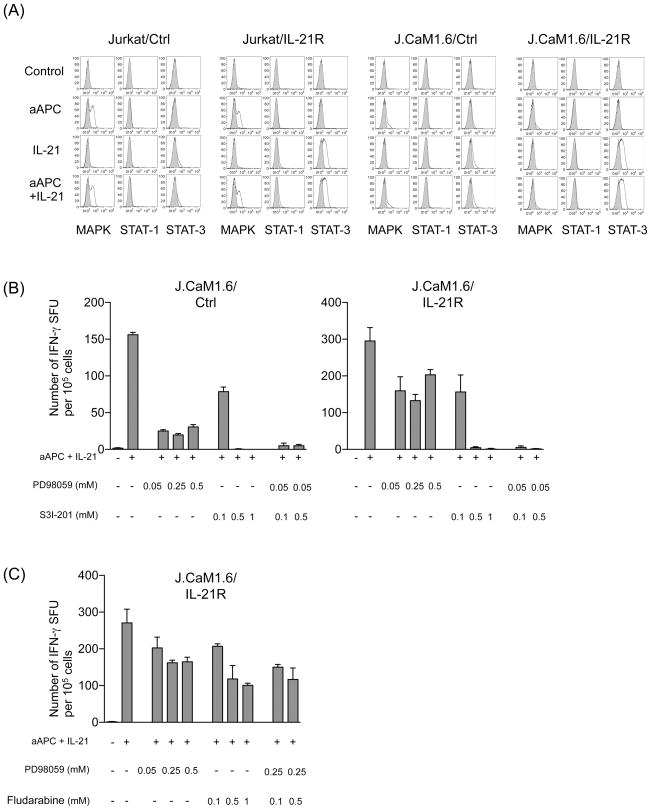

Intracellular staining revealed that IL-21 induced robust phosphorylation of STAT3 upon stimulation with mOKT3-aAPC in the presence of IL-21 in both IL-21R-transduced Jurkat and J.CaM1.6 (Figure 7A). As expected, MAPK phosphorylation was minimal in either of J.CaM1.6 transfectants probably because of the lack of Lck activation. No STAT1 phosphorylation was observed in any of the cell lines. Since polyclonal potent T cell stimulation was provided by anti-CD3 mAb-expressing mOKT3-aAPC, the level of phosphorylation in these cell lines was higher than that in primary T cells stimulated with peptide-pulsed aAPC in Figure 5A.

Figure 7. In the absence of Lck, IL-21 signaling enhances T cell responses in a STAT3- but not STAT1-dependent manner.

(A) IL-21 induces robust phosphorylation of STAT3 in the absence of Lck. Jurkat cell line and its Lck-null derivative, J.CaM1.6, stably expressing mock or IL-21R were stimulated with mOKT3-aAPC (aAPC) in the presence or absence of IL-21. The phosphorylation level of MAPK (pMAPK), STAT1 (pSTAT1) and STAT3 (pSTAT3) was determined by intracellular staining using specific mAbs for phosphorylated molecules in a flow cytometry analysis. Isotype mAb staining was used to as a control. Similar experiments were repeated 3 times. (B) IFN-γ secretion induced by aAPC + IL-21 in the absence of Lck is STAT3-dependent. Lck-null J.CaM1.6/Ctrl and J.CaM1.6/IL-21R were stimulated with mOKT3-aAPC and IL-21 in the presence of graded concentrations of inhibitors against MAPK (PD98059) and/or STAT3 (S3I-201). Similar experiments were repeated 3 times. (C) J.CaM1.6/IL-21R cells were stimulated with mOKT3-aAPC and IL-21 in the presence of graded concentrations of inhibitors against MAPK (PD98059) and/or STAT1 (Fludarabine). IFN-γ secretion was analyzed by an ELISPOT assay as depicted in Figure 6. Similar experiments were repeated 3 times.

To further study the functional role of STAT3 in Lck-independent IL-21 signaling, J.CaM1.6/Ctrl and IL-21R-transduced J.CaM1.6/IL-21R cells were stimulated by aAPC plus IL-21 in the presence of specific inhibitors (Figures 7B). In both cell lines, IFN-γ secretion was completely abrogated by STAT3 inhibition, indicating a critical role of STAT3 in IFN-γ secretion in the absence of Lck. While the MAPK inhibitor blocked IFN-γ secretion by greater than 80% in J.CaM1.6/Ctrl, it did so by less than 50% in J.CaM1.6/IL-21R cells. This suggests that, in cells lacking Lck, IL-21-induced enhancement of T cell responses is mediated by two pathways: one both STAT3- and MAPK-dependent and the other STAT3-dependent but MAPK-independent. The combination of suboptimal doses of both the STAT3 inhibitor with the MAPK inhibitor completely nullified the IFN-γ secretion, demonstrating an additive effect between STAT3 and MAPK inhibitors. In contrast, STAT1 only partially inhibited the T cell responses in J.CaM1.6/IL-21R cells (Figure 7C). The addition of the STAT1 inhibitor to the MAPK inhibitor did not demonstrate an additive effect. These results suggest that STAT3 but not STAT1-mediated IL-21 signaling can rescue the suboptimal MAPK activity caused by the lack of Lck.

Discussion

It is well accepted that biological responses of CTL such as proliferation, cytokine secretion, and cytotoxicity require different levels of T cell activation as determined by the level of TCR occupancy and signal intensity elicited by TCR engagement (44, 47). In general, proliferation requires the strongest activation signals while cytotoxicity requires the least. To determine whether CD8 coligation is necessary for immunologically functional CTL activation, most previous in vitro studies have employed measurements of effector functions, which are more “sensitive” biological responses than proliferation. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, TCR or T cell clones used in the previous studies were virtually all derived from T cells originally primed in the presence of CD8 coligation. Therefore, little is known regarding the absolute requirement of CD8 coreceptor engagement for priming of post-thymic naïve peripheral CD8+ T cells and for their proliferation as antigen-specific CTL. We previously reported that wt A2-expresssing aAPC (K562 transduced with wt HLA-A2, CD80, and CD83) can prime naïve CD8+ T cells and expand antigen-specific CD8+ CTL (27, 28, 31, 34, 35). Using a modified aAPC expressing mutant A2 (D227K/T228A) which has abrogated CD8 binding, we addressed this question in vitro in humans.

We have found that in the absence of CD8 coligation, it is virtually impossible to prime and expand antigen-specific CTL in vitro, even in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15. However, the addition of IL-21 to T cell cultures enables the priming and subsequent expansion of antigen-specific CTL in some individuals. Obviously, in this study, it was imperative to use a CD8+ T cell epitope against which generating CTL from naïve T cells using wt-aAPC is always successful. Otherwise, failure to prime naïve CD8+ T cells and/or to subsequently expand antigen-specific CD8+ T cells could be simply attributed to a low number of pCTL. This study mainly used the MART127 antigenic peptide since we and others have intensively studied this HLA-A2-restricted immunogenic CD8+ CTL epitope (48–50). MART127 is unique since it is one of the antigens for which the greatest number of pCTL are detectable (51, 52). pCTL are detectable by tetramer (<0.05%) in nearly half of A2+ healthy donors and are immunologically and phenotypically naïve (42, 43). Using K562-based wt-aAPC, we have successfully established MART127-specific CTL from greater than 100 HLA-A*0201+ individuals tested without failure in our laboratory. Our results demonstrate that the role of CD8 coreceptor coengagement is critical even for MART127, which is by far the easiest antigen for growing CD8+ CTL. Therefore, the generation of CD8+ T cell responses against other antigens, whose pCTL inevitably undergo central selection, resulting in low numbers and avidity, is also most likely highly dependent on engagement of the CD8 coreceptor.

Wt-aAPC can prime naïve CD8+ T cells in vitro and is capable of expanding MART127-specific CTL in a similar manner to dendritic cells (DC) (28, 31, 34, 35). However, we cannot definitively state whether our findings in this study can be applied to professional APC such as dendritic cells (DC). In humans, it remains technically challenging to completely eradicate endogenous HLA expression and express only one allele of mutated HLA like mut-aAPC. An alternative method to confirm our findings with mature DC might be the use of blocking mAb against CD8. However, it has been reported that anti-CD8 mAbs possess multiple effects on the interaction between MHC and TCR that cannot be explained by a simple disruption of the pMHC/CD8 interaction (53, 54). Furthermore, all anti-CD8 mAbs tested induce tyrosine-phosphorylation of T cell signaling molecules (53, 54). Therefore, at this moment, we are unable to confirm our findings using K562-based aAPC with mature DC in humans.

CTL that possess high functional avidity are known to be optimal for the clearance of pathogens and tumors in vivo. Therefore, induction of such CTL is critical for the success of cellular immunotherapeutics. In vivo, several factors have been suggested that can modulate functional avidity: TCR affinity (10–12, 55), expression level of costimulatory molecules (56, 57), IL-12 and IL-15 (30, 58), and the level of CD8 expression (38, 59). Less is known about the parameters that determine the functional avidity of CTL in vitro. Previous studies demonstrated that the functional avidity of the CTL lines generated in vitro was inversely correlated with the peptide densities presented by stimulating APC (60). Based on this, some groups have selectively generated CTL with high functional avidity by stimulating with APC pulsed with low doses of peptide (59, 61). In addition, it has been reported that IL-21 can selectively expand highly avid CTL in vitro (62). In this context, our finding that CD8-independent stimulation supplemented by IL-21 treatment can grow CTL is intriguing. Low doses of peptide will decrease the magnitude of TCR engagement/CD3 signaling by lowering the number of TCR/CD3 complexes engaged but will not likely affect the quality of the signal. In contrast, CD8-independent T cell stimulation will not change the quantity of TCR/CD3 complexes engaged. Instead, it will change the quality of signaling by specifically abrogating the downstream effects of CD8 molecules. It is yet to be determined whether a change in quantity or quality is better for generating CTL grafts for clinically effective adoptive immunotherapy. It should be noted that high functional avidity is just one of the requirements of CTL for adoptive transfer. Adoptively transferred CTL must be able to expand, persist, and traffic to the target cells in vivo.

Humans with CD8 deficiency have been reported (19). Among three family members with complete absence of CD8+ T cells, one suffered from mild chronic infections while the other two appeared healthy. These results suggest that there might be a mechanism to counterbalance the loss of CD8 expression in vivo. In this context, our finding that IL-21 can supplement partial T cell stimulation caused by the lack of CD8 coligation in vitro is intriguing. Many investigators including us previously reported a unique function of IL-21 that can modulate the quantity and quality of CD8+ CTL (21, 63). IL-21 is predominantly secreted by activated CD4+ T cells but not by CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, recent in vivo experiments using mouse models showed that IL-21 can be a mediator of CD4+ T cell help to CD8+ T cells (64–66). It is conceivable that, in these patients with total CD8 deficiency, IL-21 secreted by CD4+ T cells may play a critical role to correct the low number of CTL by enhancing the CTL’s function and ability to eliminate pathogens.

There were some donors from whom we were not able to expand MART127-specific CTL using mut-aAPC and IL-21. We studied greater than 30 healthy individuals for the expression level of IL-21R on T cells upon activation (data not shown). Although none of their resting T cells expressed IL-21R, there was great diversity in the induced expression level of IL-21R among the individuals. We speculated that, in those patients who were unable to expand MART127-specific CTL using mut-aAPC and IL-21, the expression level of IL-21R on MART127 pCTL was not sufficient to transmit IL-21 mediated supplementary signaling. Unfortunately, T cell activation required for the induction of IL-21R expression downregulates the expression of TCR and CD8. Therefore, it was impractical to compare the IL-21R expression on less than 0.05% multimer-positive MART127 pCTL upon activation.

K562-based wt-aAPC can generate large numbers of antigen-specific CD8+ CTL with a central memory~effector memory phenotype consistent with in vivo persistence (28). These CTL recognize tumor cells with sufficient avidity, are surprisingly long-lived, and can be maintained in vitro for >1 year. We have conducted a clinical trial where large numbers of MART1-specific CD8+ CTL generated in vitro using this wt-aAPC and IL-2/IL-15 are adoptively transferred to patients with metastatic melanoma (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00512889). These CTL were able to persist in patients without previous conditioning or cytokine treatment. Moreover, they trafficked to the tumor, mediated biological and clinical responses, and established antitumor immunologic memory (67). It is well known that CTL with high functional avidity are optimal for the clearance of pathogens and tumors in mice. Upon adoptive transfer, CTL with higher functional avidity generated using mut-aAPC and IL-21 may be more clinically effective than CTL generated using wt-aAPC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grants, K22CA129240 and R01CA148673 (to NH). MT, MOB, and LMN were supported with funds from the Cancer Research Institute. NH was supported by the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award.

We would like to thank Zhinan Xia and Keiko Nishida for the generation of tetramers.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- aAPC

artificial APC

- pMHC

peptide/MHC

- wt

wild type

- mut

mutant

- pCTL

precursor CTL

- ctrl

control

- mOKT3

membranous form of OKT3

References

- 1.Zamoyska R. CD4 and CD8: modulators of T-cell receptor recognition of antigen and of immune responses? Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:82–87. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luescher IF, Vivier E, Layer A, Mahiou J, Godeau F, Malissen B, Romero P. CD8 modulation of T-cell antigen receptor-ligand interactions on living cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1995;373:353–356. doi: 10.1038/373353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wooldridge L, van den Berg HA, Glick M, Gostick E, Laugel B, Hutchinson SL, Milicic A, Brenchley JM, Douek DC, Price DA, Sewell AK. Interaction between the CD8 coreceptor and major histocompatibility complex class I stabilizes T cell receptor-antigen complexes at the cell surface. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:27491–27501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500555200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purbhoo MA, Boulter JM, Price DA, Vuidepot AL, Hourigan CS, Dunbar PR, Olson K, Dawson SJ, Phillips RE, Jakobsen BK, Bell JI, Sewell AK. The human CD8 coreceptor effects cytotoxic T cell activation and antigen sensitivity primarily by mediating complete phosphorylation of the T cell receptor zeta chain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:32786–32792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veillette A, Bookman MA, Horak EM, Bolen JB. The CD4 and CD8 T cell surface antigens are associated with the internal membrane tyrosine-protein kinase p56lck. Cell. 1988;55:301–308. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buslepp J, Kerry SE, Loftus D, Frelinger JA, Appella E, Collins EJ. High affinity xenoreactive TCR:MHC interaction recruits CD8 in absence of binding to MHC. J Immunol. 2003;170:373–383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holler PD, Kranz DM. Quantitative analysis of the contribution of TCR/pepMHC affinity and CD8 to T cell activation. Immunity. 2003;18:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerry SE, Buslepp J, Cramer LA, Maile R, Hensley LL, Nielsen AI, Kavathas P, Vilen BJ, Collins EJ, Frelinger JA. Interplay between TCR affinity and necessity of coreceptor ligation: high-affinity peptide-MHC/TCR interaction overcomes lack of CD8 engagement. J Immunol. 2003;171:4493–4503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laugel B, Price DA, Milicic A, Sewell AK. CD8 exerts differential effects on the deployment of cytotoxic T lymphocyte effector functions. European journal of immunology. 2007;37:905–913. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi EM, Chen JL, Wooldridge L, Salio M, Lissina A, Lissin N, Hermans IF, Silk JD, Mirza F, Palmowski MJ, Dunbar PR, Jakobsen BK, Sewell AK, Cerundolo V. High avidity antigen-specific CTLidentified by CD8-independent tetramer staining. J Immunol. 2003;171:5116–5123. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pittet MJ, Rubio-Godoy V, Bioley G, Guillaume P, Batard P, Speiser D, Luescher I, Cerottini JC, Romero P, Zippelius A. Alpha 3 domain mutants of peptide/MHC class I multimers allow the selective isolation of high avidity tumor-reactive CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:1844–1849. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price DA, Brenchley JM, Ruff LE, Betts MR, Hill BJ, Roederer M, Koup RA, Migueles SA, Gostick E, Wooldridge L, Sewell AK, Connors M, Douek DC. Avidity for antigen shapes clonal dominance in CD8+ T cell populations specific for persistent DNA viruses. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:1349–1361. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews NP, Pack CD, Lukacher AE. Generation of antiviral major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T cells in the absence of CD8 coreceptors. J Virol. 2008;82:4697–4705. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02698-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crooks ME, Littman DR. Disruption of T lymphocyte positive and negative selection in mice lacking the CD8 beta chain. Immunity. 1994;1:277–285. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fung-Leung WP, Kundig TM, Ngo K, Panakos J, De Sousa-Hitzler J, Wang E, Ohashi PS, Mak TW, Lau CY. Reduced thymic maturation but normal effector function of CD8+ T cells in CD8 beta gene-targeted mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1994;180:959–967. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riddle DS, Miller PJ, Vincent BG, Kepler TB, Maile R, Frelinger JA, Collins EJ. Rescue of cytotoxic function in the CD8alpha knockout mouse by removal of MHC class II. European journal of immunology. 2008;38:1511–1521. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angelov GS, Guillaume P, Luescher IF. CD8beta knockout mice mount normal anti-viral CD8+ T cell responses--but why? International immunology. 2009;21:123–135. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakayama K, Negishi I, Kuida K, Louie MC, Kanagawa O, Nakauchi H, Loh DY. Requirement for CD8 beta chain in positive selection of CD8-lineage T cells. Science (New York, NY. 1994;263:1131–1133. doi: 10.1126/science.8108731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de la Calle-Martin O, Hernandez M, Ordi J, Casamitjana N, Arostegui JI, Caragol I, Ferrando M, Labrador M, Rodriguez-Sanchez JL, Espanol T. Familial CD8 deficiency due to a mutation in the CD8 alpha gene. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2001;108:117–123. doi: 10.1172/JCI10993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma A, Koka R, Burkett P. Diverse functions of IL-2, IL-15, and IL-7 in lymphoid homeostasis. Annual review of immunology. 2006;24:657–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spolski R, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-21: basic biology and implications for cancer and autoimmunity. Annual review of immunology. 2008;26:57–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rochman Y, Spolski R, Leonard WJ. New insights into the regulation of T cells by gamma(c) family cytokines. Nature reviews. 2009;9:480–490. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Lupardus P, Laporte SL, Garcia KC. Structural biology of shared cytokine receptors. Annual review of immunology. 2009;27:29–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bezbradica JS, Medzhitov R. Integration of cytokine and heterologous receptor signaling pathways. Nature immunology. 2009;10:333–339. doi: 10.1038/ni.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verdeil G, Chaix J, Schmitt-Verhulst AM, Auphan-Anezin N. Temporal cross-talk between TCR and STAT signals for CD8 T cell effector differentiation. European journal of immunology. 2006;36:3090–3100. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAdam AJ, Gewurz BE, Farkash EA, Sharpe AH. Either B7 costimulation or IL-2 can elicit generation of primary alloreactive CTL. J Immunol. 2000;165:3088–3093. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ansen S, Butler MO, Berezovskaya A, Murray AP, Stevenson K, Nadler LM, Hirano N. Dissociation of its opposing immunologic effects is critical for the optimization of antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses induced by interleukin 21. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6125–6136. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butler MO, Lee JS, Ansen S, Neuberg D, Hodi FS, Murray AP, Drury L, Berezovskaya A, Mulligan RC, Nadler LM, Hirano N. Long-lived antitumor CD8+ lymphocytes for adoptive therapy generated using an artificial antigen-presenting cell. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1857–1867. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Bleakley M, Yee C. IL-21 influences the frequency, phenotype, and affinity of the antigen-specific CD8 T cell response. J Immunol. 2005;175:2261–2269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh S, Perera LP, Burke DS, Waldmann TA, Berzofsky JA. IL-15/IL-15Ralpha-mediated avidity maturation of memory CD8+ T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:15154–15159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406649101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirano N, Butler MO, Xia Z, Ansen S, von Bergwelt-Baildon MS, Neuberg D, Freeman GJ, Nadler LM. Engagement of CD83 ligand induces prolonged expansion of CD8+ T cells and preferential enrichment for antigen specificity. Blood. 2006;107:1528–1536. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuzushima K, Hayashi N, Kudoh A, Akatsuka Y, Tsujimura K, Morishima Y, Tsurumi T. Tetramer-assisted identification and characterization of epitopes recognized by HLA A*2402-restricted Epstein-Barr virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2003;101:1460–1468. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez OD, Mitchell D, Campos R, Gao GJ, Li L, Nolan GP. Multiparameter analysis of intracellular phosphoepitopes in immunophenotyped cell populations by flow cytometry. Curr Protoc Cytom Chapter. 2005;6(Unit 6):20. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0620s32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirano N, Butler MO, Xia Z, Berezovskaya A, Murray AP, Ansen S, Kojima S, Nadler LM. Identification of an immunogenic CD8+ T-cell epitope derived from gamma-globin, a putative tumor-associated antigen for juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:2662–2668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirano N, Butler MO, Xia Z, Berezovskaya A, Murray AP, Ansen S, Nadler LM. Efficient presentation of naturally processed HLA class I peptides by artificial antigen-presenting cells for the generation of effective antitumor responses. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2967–2975. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheroutre H. IELs: enforcing law and order in the court of the intestinal epithelium. Immunological reviews. 2005;206:114–131. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karaki S, Tanabe M, Nakauchi H, Takiguchi M. Beta-chain broadens range of CD8 recognition for MHC class I molecule. J Immunol. 1992;149:1613–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renard V, Romero P, Vivier E, Malissen B, Luescher IF. CD8 beta increases CD8 coreceptor function and participation in TCR-ligand binding. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1996;184:2439–2444. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wheeler CJ, von Hoegen P, Parnes JR. An immunological role for the CD8 beta-chain. Nature. 1992;357:247–249. doi: 10.1038/357247a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wooldridge L, Clement M, Lissina A, Edwards ES, Ladell K, Ekeruche J, Hewitt RE, Laugel B, Gostick E, Cole DK, Debets R, Berrevoets C, Miles JJ, Burrows SR, Price DA, Sewell AK. MHC class I molecules with Superenhanced CD8 binding properties bypass the requirement for cognate TCR recognition and nonspecifically activate CTLs. J Immunol. 2010;184:3357–3366. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laugel B, van den Berg HA, Gostick E, Cole DK, Wooldridge L, Boulter J, Milicic A, Price DA, Sewell AK. Different T cell receptor affinity thresholds and CD8 coreceptor dependence govern cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation and tetramer binding properties. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:23799–23810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salio M, Shepherd D, Dunbar PR, Palmowski M, Murphy K, Wu L, Cerundolo V. Mature dendritic cells prime functionally superior melan-A-specific CD8+ lymphocytes as compared with nonprofessional APC. J Immunol. 2001;167:1188–1197. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zippelius A, Batard P, Rubio-Godoy V, Bioley G, Lienard D, Lejeune F, Rimoldi D, Guillaume P, Meidenbauer N, Mackensen A, Rufer N, Lubenow N, Speiser D, Cerottini JC, Romero P, Pittet MJ. Effector function of human tumor-specific CD8 T cells in melanoma lesions: a state of local functional tolerance. Cancer research. 2004;64:2865–2873. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valitutti S, Muller S, Dessing M, Lanzavecchia A. Different responses are elicited in cytotoxic T lymphocytes by different levels of T cell receptor occupancy. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1996;183:1917–1921. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessler B, Hudrisier D, Schroeter M, Tschopp J, Cerottini JC, Luescher IF. Peptide modification or blocking of CD8, resulting in weak TCR signaling, can activate CTL for Fas- but not perforin-dependent cytotoxicity or cytokine production. J Immunol. 1998;161:6939–6946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu XN, Purbhoo MA, Chen N, Mongkolsapaya J, Cox JH, Meier UC, Tafuro S, Dunbar PR, Sewell AK, Hourigan CS, Appay V, Cerundolo V, Burrows SR, McMichael AJ, Screaton GR. A novel approach to antigen-specific deletion of CTL with minimal cellular activation using alpha3 domain mutants of MHC class I/peptide complex. Immunity. 2001;14:591–602. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hemmer B, Stefanova I, Vergelli M, Germain RN, Martin R. Relationships among TCR ligand potency, thresholds for effector function elicitation, and the quality of early signaling events in human T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:5807–5814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kawakami Y, Rosenberg SA. Human tumor antigens recognized by T-cells. Immunol Res. 1997;16:313–339. doi: 10.1007/BF02786397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pittet MJ, Zippelius A, Valmori D, Speiser DE, Cerottini JC, Romero P. Melan-A/MART-1-specific CD8 T cells: from thymus to tumor. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romero P, Valmori D, Pittet MJ, Zippelius A, Rimoldi D, Levy F, Dutoit V, Ayyoub M, Rubio-Godoy V, Michielin O, Guillaume P, Batard P, Luescher IF, Lejeune F, Lienard D, Rufer N, Dietrich PY, Speiser DE, Cerottini JC. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of Melan-A/MART-1 derived peptides as targets for tumor reactive CTL in human melanoma. Immunological reviews. 2002;188:81–96. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alanio C, Lemaitre F, Law HK, Hasan M, Albert ML. Enumeration of human antigen-specific naive CD8+ T cells reveals conserved precursor frequencies. Blood. 2010;115:3718–3725. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-251124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blattman JN, Antia R, Sourdive DJ, Wang X, Kaech SM, Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Ahmed R. Estimating the precursor frequency of naive antigen-specific CD8 T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;195:657–664. doi: 10.1084/jem.20001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wooldridge L, Hutchinson SL, Choi EM, Lissina A, Jones E, Mirza F, Dunbar PR, Price DA, Cerundolo V, Sewell AK. Anti-CD8 antibodies can inhibit or enhance peptide-MHC class I (pMHCI) multimer binding: this is paralleled by their effects on CTL activation and occurs in the absence of an interaction between pMHCI and CD8 on the cell surface. J Immunol. 2003;171:6650–6660. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wooldridge L, Scriba TJ, Milicic A, Laugel B, Gostick E, Price DA, Phillips RE, Sewell AK. Anti-coreceptor antibodies profoundly affect staining with peptide-MHC class I and class II tetramers. European journal of immunology. 2006;36:1847–1855. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yee C, Savage PA, Lee PP, Davis MM, Greenberg PD. Isolation of high avidity melanoma-reactive CTL from heterogeneous populations using peptide-MHC tetramers. J Immunol. 1999;162:2227–2234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hodge JW, Chakraborty M, Kudo-Saito C, Garnett CT, Schlom J. Multiple costimulatory modalities enhance CTL avidity. J Immunol. 2005;174:5994–6004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.5994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oh S, Hodge JW, Ahlers JD, Burke DS, Schlom J, Berzofsky JA. Selective induction of high avidity CTL by altering the balance of signals from APC. J Immunol. 2003;170:2523–2530. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu S, Koski GK, Faries M, Bedrosian I, Mick R, Maeurer M, Cheever MA, Cohen PA, Czerniecki BJ. Rapid high efficiency sensitization of CD8+ T cells to tumor antigens by dendritic cells leads to enhanced functional avidity and direct tumor recognition through an IL-12-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;171:2251–2261. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cawthon AG, Lu H, Alexander-Miller MA. Peptide requirement for CTL activation reflects the sensitivity to CD3 engagement: correlation with CD8alphabeta versus CD8alphaalpha expression. J Immunol. 2001;167:2577–2584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alexander-Miller MA, Leggatt GR, Berzofsky JA. Selective expansion of high- or low-avidity cytotoxic T lymphocytes and efficacy for adoptive immunotherapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:4102–4107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walter S, Herrgen L, Schoor O, Jung G, Wernet D, Buhring HJ, Rammensee HG, Stevanovic S. Cutting edge: predetermined avidity of human CD8 T cells expanded on calibrated MHC/anti-CD28-coated microspheres. J Immunol. 2003;171:4974–4978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li J, Shen W, Kong K, Liu Z. Interleukin-21 induces T-cell activation and proinflammatory cytokine secretion in rheumatoid arthritis. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2006;64:515–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skak K, Kragh M, Hausman D, Smyth MJ, Sivakumar PV. Interleukin 21: combination strategies for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:231–240. doi: 10.1038/nrd2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elsaesser H, Sauer K, Brooks DG. IL-21 is required to control chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.1174182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frohlich A, Kisielow J, Schmitz I, Freigang S, Shamshiev AT, Weber J, Marsland BJ, Oxenius A, Kopf M. IL-21R on T cells is critical for sustained functionality and control of chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1576–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.1172815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yi JS, Du M, Zajac AJ. A Vital Role for Interleukin-21 in the Control of a Chronic Viral Infection. Science. 2009;324:1572–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.1175194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Butler MO, Friedlander P, Milstein MI, Mooney MM, Metzler G, Murray AP, Tanaka M, Berezovskaya A, Imataki O, Drury L, Brennan L, Flavin M, Neuberg D, Stevenson K, Lawrence D, Hodi FS, Velazquez EF, Jaklitsch MT, Russell SE, Mihm M, Nadler LM, Hirano N. Establishment of antitumor memory in humans using in vitro-educated CD8+ T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:80ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.