Abstract

We examined gene expression in the lumbar spinal cord and the specific response of motoneurons, intermediate gray and proprioceptive sensory neurons after spinal cord injury and exercise of hindlimbs to identify potential molecular processes involved in activity dependent plasticity. Adult female rats received a low thoracic transection and passive cycling exercise for 1 or 4 weeks. Gene expression analysis focused on the neurotrophic factors; brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), neurotrophin-4 (NT-4), and their receptors because of their potential roles in neural plasticity. We also examined expression of genes involved in the cellular response to injury; heat shock proteins (HSP) -27 and -70, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and caspases -3, -7, and -9. In lumbar cord samples, injury increased the expression of mRNA for TrkB, all three caspases and the HSPs. Acute and prolonged exercise increased expression of mRNA for the neurotrophic factors BDNF and GDNF, but not their receptors. It also increased HSP expression and decreased caspase-7 expression, with changes in protein levels complimentary to these changes in mRNA expression.

Motoneurons and intermediate grey displayed little change in mRNA expression following injury, but acute and prolonged exercise increased levels of mRNA for BDNF, GDNF and NT-4. In large DRG neurons, mRNA for neurotrophic factors and their receptors were largely unaffected by either injury or exercise. However, caspase mRNA expression was increased by injury and decreased by exercise. Our results demonstrate that exercise affects expression of genes involved in plasticity and apoptosis in a cell specific manner and that these change with increased post-injury intervals and/or prolonged periods of exercise.

Keywords: Spinal cord, transection, exercise, neuroplasticity, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor

1. Introduction

Complete spinal cord injury (SCI) disrupts the transmission of both descending projections to motoneurons and ascending sensory projections. Below the lesion, ventral horn motoneurons retain their connection to their target muscle, but the loss of supraspinal input results in spastic paralysis, marked by flaccidity of the trunk and limbs with bouts of spasticity. Large DRG neurons, responsible for conveying proprioceptive information about muscle stretch, retain their connections in the spinal cord grey matter, but suffer a collateral axotomy that results in loss of conscious and unconscious muscle perception. However, the innate ability of the central nervous system to modify synaptic connections and functions (neuroplasticity) allows for remodeling of motor and sensory systems which can result in extensive functional effects.

Natural recovery mechanisms alone, such as sprouting, gliogenesis and synaptic reorganization are unable to overcome obstacles to regeneration, but treatment with rhythmic patterned activity or exercise (Ex), can enhance some recovery of function (de Leon et al., 1998; Lovely et al., 1986). Activity-dependent plasticity has been observed in animal models of SCI (Beaumont et al., 2004; De Leon et al., 1999; Sandrow-Feinberg et al., 2009) as well as in human studies (Astorino et al., 2008; Phadke et al., 2009). Indeed, beneficial aspects of exercise likely stem from its ability to stimulate spinal circuits (Edgerton and Roy, 2009; Ollivier-Lanvin et al., 2010) and to increase local levels of trophic factors (Gomez-Pinilla et al., 2001; Gomez-Pinilla et al., 2002; Sandrow-Feinberg et al., 2009; Côté et al., 2011). Because of their distinct roles, we investigated changes in gene expression in motor and proprioceptive sensory neurons in response to spinal cord injury and Ex, with a focus on genes associated with plasticity and injury. Because of their ability to affect neural plasticity we examined the expression of selected neurotrophic factors and their receptors.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and neurotrophin-4 (NT-4) act as chemo-attractants for regenerating axons (Bregman et al., 1997; Dolbeare and Houle, 2003; Nothias et al., 2005; Ye and Houle, 1997) and are capable of modifying neuronal circuits by strengthening and increasing the formation of synapses (Gomez-Pinilla et al., 2002). The selectivity of expression of receptors for these neurotrophic factors may act as a targeting mechanism for different populations of neurons. Mapping the expression of neurotrophic factors and their receptors may provide insight into regions of change in neuronal circuits.

Cell death and glial reactivity limit the potential of activity-dependent plasticity by eliminating neuronal targets and preventing axonal growth through an inhibitory environment. To investigate factors related to cell survival we examined changes in the expression of mRNA and protein for heat shock proteins HSP-27 and HSP-70 which act as chaperones of protein folding and as cell survival factors. We also examined changes in expression of Caspase-3, Caspase-7 and Caspase-9 because of their involvement in the apoptotic pathway and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) as an indicator of glial reactivity, as astrocytes produce and secrete factors inhibitory to axonal growth and are a major constituent of the glial scar.

We examined mRNA changes in laser micro dissected spinal motoneurons (the final output of the motor system) and intermediate grey matter (the collection of neurons and glia involved in transmitting and integrating information between the sensory and motor systems). From the sensory system we examined large neurons isolated from the DRG because of their responsibility for conveying proprioceptive information to the spinal cord. Relative levels of mRNA and protein were compared in whole cord samples using quantitative PCR and Western blot techniques; however, due to limited LMD sample availability protein levels could not be accurately quantified in LMD isolated samples.

To study the effects of exercise, spinalized rats received a daily regimen of passive cycling, which moves the hindlimbs of the animal through a full range of motion. We have previously shown that this exercise paradigm is capable of modifying molecular and physiological aspects of the lumbar spinal cord and hindlimb muscles (Skinner et al., 1996; Dupont-Versteegden et al., 1998; Ollivier-Lanvin et al., 2010). To determine if the activity dependent response is maintained over time, the effects of short (1 week) and long term (4 weeks) bouts of exercise were compared. By demonstrating changes at a molecular level of activity-dependent plasticity we can seek to enhance training and behavioral outcome for individuals affected by SCI.

2. Results

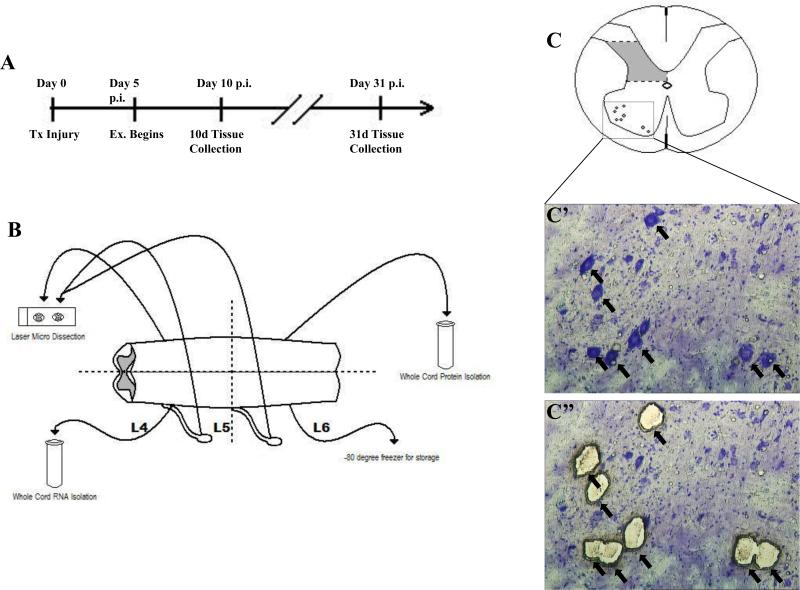

We first examined mRNA and protein levels in whole cord samples caudal to an injury to determine how loss of supraspinal input to the lumbar enlargement affected gene expression in white and grey matter. We then measured expression in specific cells or regions isolated by LMD, including motoneurons (Figure 1), intermediate grey matter and large DRG neurons. To identify changes in gene expression due to activity, we measured changes in expression after short (5d) and longer (20d) bicycle training regimens that resulted in post-injury sacrifice times of 10 and 31 days. All results were normalized to intact control animals and all error bars reflect the standard deviation of the groups. Descriptions of changes in gene expression over time consist of “persistent” and “sustained” to address changes in the same direction over the course of the experiments, while the term “transient” was used to describe changes in gene expression that were altered initially, but returned to baseline levels over the course of experiments. The term “delayed” is used to describe a change occurring only at the later time point.

Figure 1.

Experimental design. A) Timeline of injury, exercise (Ex) and tissue collection. B) Schematic showing how spinal cord and DRG tissue was collected for later analysis. C) Diagram of regions used for laser micro dissected sections from spinal cord. Shaded area indicates intermediate grey matter. Motoneurons were isolated from the boxed area. C’) Spinal cord ventral horn. Arrows indicate motoneurons before laser capture. C’’) Spinal cord ventral horn after laser micro dissection. Arrows indicate position of isolated motoneurons.

2.1 Whole Cord mRNA

2.1.1 mRNA expression changes after SCI

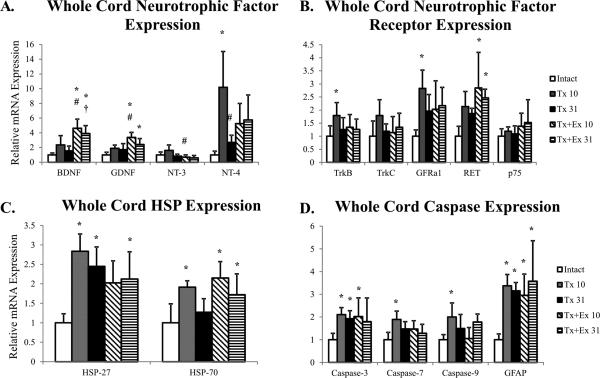

Among the neurotrophic factors probed, a complete transection injury had significant effect only on NT-4 mRNA expression. There was a transient increase in the expression of NT-4 mRNA, mRNA for its receptor, TrkB and for GFRα1 (Figure 2A-B) but at 31 days, mRNA expression was not different from the control for any of these molecules (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Whole spinal cord mRNA expression from intact, transected (Tx 10, Tx 31), and transected plus exercise (Tx+Ex 10, Tx+Ex 31) rats (n=6 for all groups). A) mRNA expression of neurotrophic factors in whole cord tissue. B) mRNA expression of neurotrophic factor receptors in whole cord tissue. C) mRNA expression of HSPs in whole cord tissue. D) mRNA expression of Caspases in whole cord tissue. Error bars are indicative of standard deviation of groups. * indicates significantly different from intact; # indicates significantly different from Tx 10; † indicates significantly different from Tx 31.

HSP-27 mRNA showed a persistent increase in expression, lasting through day 31 (Figure 2C), while an increase in HSP-70 mRNA occurred at the early but not later post-injury period (Figure 2C). Caspase mRNA expression also was increased by transection injury and differences between the isoforms were apparent. Caspase-3 mRNA showed a persistent increase, while mRNA for caspases-7 and -9 showed only a transient increase (Figure 2D). GFAP, an indicator of astrocyte reactivity, showed sustained increases in mRNA expression following transection injury (Figure 2D).

2.1.2 mRNA expression changes due to cycling exercise following SCI

When transection was followed by exercise there were profound effects on neurotrophic factor expression. mRNA for both BDNF and GDNF showed persistent increases in expression with exercise (Figure 2A). The effects on NT-3 mRNA expression were, however, quite different. Exercise following transection decreased mRNA for NT-3 in whole cord tissue compared to transection alone (Figure 2A). Likewise, exercise also attenuated the injury induced increase in NT-4 mRNA such that it was no longer different from control (Figure 2A). Increases in TrkB and GFRα1 mRNA, observed following transection, were also attenuated by exercise. The expression of mRNA for RET, part of the GDNF receptor complex, was the only receptor showing a sustained response to exercise (Figure 2B).

Exercise had effects on HSP and caspase mRNA expression. It attenuated the injury induced increase in HSP-27 mRNA at 10 days (Figure 2C), and sustained the increase in HSP-70 mRNA for 31 days (Figure 2C). Exercise reduced the injury induced increase in caspases -7 and -9 (Figure 2D), but had no effect on the expression of Caspase-3 or GFAP (Figure 2D).

2.2 Whole Cord Protein

2.2.1 Protein expression changes after SCI

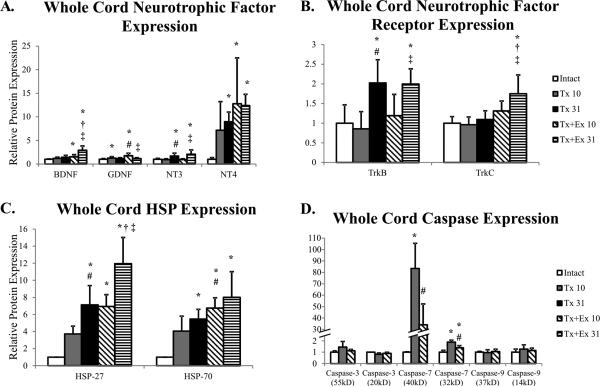

Levels of GDNF protein were increased following transection, but returned to control levels by 31 days (Figure 3A). Both NT-3 and NT-4 showed a delayed increase in protein levels (Figure 3A) that was preceded by a transient increase in NT-4 mRNA (Figure 2A). TrkB, the receptor for NT-4, also displayed a delayed increase in protein (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Whole spinal cord protein expression of intact, transected (Tx 10, Tx 31), and transected plus exercise (Tx+Ex 10, Tx+Ex 31) rats (n=6 for all groups). A) Protein expression of neurotrophic factors in whole cord tissue. B) Protein expression of neurotrophic factor receptors in whole cord tissue. C) Protein expression of HSPs in whole cord tissue. D) Protein expression of Caspases in whole cord tissue. Error bars are indicative of standard deviation of groups. * indicates significantly different from intact; # indicates significantly different from Tx 10; † indicates significantly different from Tx 31; ‡ indicates significantly different from Tx+Ex 10.

A delayed increase in protein levels was observed with both HSP-27 and HSP-70 (Figure 3C). We also observed a significant increase in levels of Caspase-7 with transection (Figure 3D). Caspases are activated through a series of cleavages and formation of heterodimers allowing for multiple isoforms to be visualized on a Western blot (see Figure 7 Liu et al., 2010). Expression of only the isoforms of Caspase-7 was affected by thoracic transection (Figure 3D).

2.2.2 Protein expression changes due to cycling exercise following SCI

Exercise had considerable effects on neurotrophic factor protein levels in the whole cord. Exercise resulted in a sustained increase in levels of BDNF. At 10 days BDNF levels were increased over intact animals (Figure 3A) and increased over time, such that they were also significantly higher than Tx 31 and Tx+Ex animals at 31 days (Figure 3A). Unlike BDNF, levels of TrkB protein were unchanged by exercise, with levels at 31 days comparable to injury only animals (Figure 3B). Exercise resulted in a transient increase in GDNF protein over transection alone at 10 days that was not sustained at 31 days (Figure 3A). Exercise had no additional effect on NT-3 protein expression compared to transection alone (Figure 3A), but TrkC, the NT-3 receptor, displayed a delayed increase with exercise. Exercise had minimal effects on NT-4 protein levels. At 10 days, exercise did not further increase levels over transection alone (Figure 3A). Levels of NT-4 at 31 days also did not differ from transection alone (Figure 3A).

HSP protein levels responded differently to exercise than what was predicted by changes in mRNA expression. Specifically, exercise resulted in a sustained increase in protein levels of HSP-27 and -70 (Figure 3C). Levels of HSP-27 were higher at both time points in exercised animals than their transected only counterparts and intact controls (Figure 3C). Like HSP-27, 10 days after transection, there was a significant increase in HSP-70 in exercised animals compared to transection only and intact controls (Figure 3C). By 31 days HSP-70 was not increased in exercised animals compared to 31 day transection alone (Figure 3C).

Similar to the transection only animals, of the caspases tested only Caspase-7 protein levels were affected by exercise Caspase-7 levels were reduced by exercise, but remained elevated above intact controls (Figure 3D).

2.3 Laser Micro Dissection: Motoneurons

We examined the effects of thoracic transection and passive exercise on motoneurons that innervate the hindlimbs at 10 and 31 days post injury. Three hundred motoneurons per animal were laser micro dissected and processed for RNA extraction from approximately the same level of tissue used for the whole cord analysis. Unlike the whole cord analysis, LMD allows gene expression analysis of a single cell type. To ensure the specificity and purity of the motoneuron samples, PCR was performed with GFAP primers to identify samples with possible astrocyte contamination, however, no GFAP expression was detected. Although, we were unable to detect any astrocyte contamination, there is a possibility that within a 20 micron section, multiple cells may be stacked and portions of other cells were erroneously collected. However, this form of contamination would likely be minimal compared to the amount of the intended target of the LMD and thus would have minimal influence on the results.

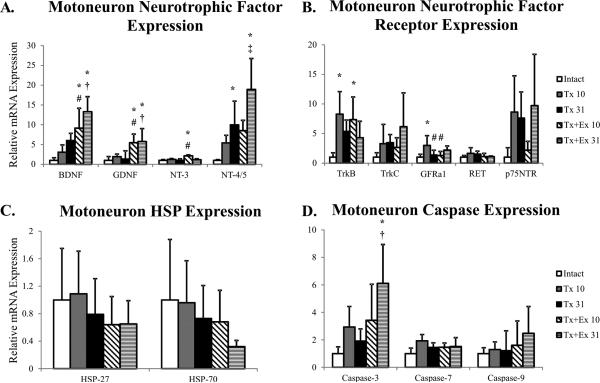

2.3.1 mRNA expression changes after SCI

Transection resulted in an increase in mRNA levels of NT-4 at 31 days after injury, and a transient increase in expression of TrkB and GFRα1 mRNA (Figure 4). Heat shock protein-27 and -70 mRNA expression was unchanged by transection, but there was a transient increase in Caspase-7 mRNA (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Gene expression in motoneurons of intact, transected (Tx 10, Tx 31), and transected plus exercise (Tx+Ex 10, Tx+Ex 31) rats (n=6 for all groups). + error is indicative of standard deviation. Grey background indicates expression of the gene is significantly altered in one of the injury-treatment groups. * indicates significantly different from intact; # indicates significantly different from Tx 10; † indicates significantly different from Tx 31; ‡ indicates significantly different from Tx+Ex 10.

2.3.2 mRNA expression changes due to cycling exercise following SCI

In contrast to transection only, exercise increased neurotrophic factor expression in motoneurons, with sustained increases in BDNF and GDNF mRNA expression and a short term increase in NT-3 mRNA expression (Figure 4). The increase in NT-4 levels at 31 days in exercised animals was significantly greater than in 10d exercised animals (Figure 4). Like transection alone, a transient increase in TrkB mRNA was observed in transected and exercised animals (Figure 4). Exercise had the opposite effect on GFRα1, resulting in an attenuation of the transection induced increase (Figure 4).

HSP-27 and -70 mRNA expression was unchanged by exercise at either 10 or 31 days, but exercise attenuated the transection induced increase in Caspase-7 mRNA (Figure 4). Surprisingly, there was a delayed increase in expression of Caspase-3 mRNA with exercise (Figure 4).

2.4 Laser Micro Dissection: Intermediate Grey Matter

Intermediate grey matter, encompassing laminae IV, V, and VI was collected by laser micro dissection and total RNA was extracted. Unlike the motoneuron sample, the intermediate grey matter sample contained a heterogeneous mixture of cells including interneurons, astrocytes, and microglia. While individual contributions of cell types could not be distinguished, gene expression analysis of this area known for sprouting of DRG axons and circuit rearrangement could be performed.

2.4.1 mRNA expression changes after SCI

Spinal transection had no effect on expression of any of the genes tested in the intermediate grey matter at ten days following injury. Expression of mRNA for neurotrophic factors, neurotrophic factor receptors, heat-shock proteins and for caspases was unchanged (Figure 5). An additional 3 weeks post injury had no effect on expression of these genes in the intermediate grey matter (Figure 5).

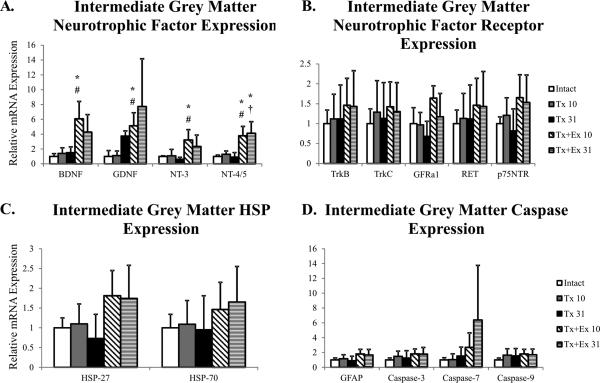

Figure 5.

Gene expression in intermediate grey matter of intact, transected (Tx 10, Tx 31), and transected plus exercise (Tx+Ex 10, Tx+Ex 31) rats(n=6 for all groups). + error is indicative of standard deviation. Grey background indicates expression of the gene is significantly altered in one of the injury-treatment groups. * indicates significantly different from intact; # indicates significantly different from Tx 10; † indicates significantly different from Tx 31.

2.4.2 mRNA expression changes due to cycling exercise following SCI

Similar to mRNA expression in motoneurons, the main effect of exercise was on gene expression of the neurotrophic factors. In the intermediate grey matter, exercise resulted in a transient increase in the expression BDNF, GDNF and NT-3 mRNA (Figure 5). NT-4 mRNA expression was also increased at 10 days and remained elevated through 31 days (Figure 5). However, exercise had no effect on mRNA expression of the probed neurotrophic factor receptors, heat shock proteins, caspases, or GFAP (Figure 5).

2.5 Laser Micro Dissection: Large DRG Neurons

We restricted our analysis to changes in gene expression in large DRG neurons (>1000μm2) which primarily transmit proprioceptive information from muscles that are directly activated by our exercise paradigm. Approximately 300 cells were collected per animal and total RNA was extracted for real-time PCR evaluation. As mentioned in section 2.3, it is possible that contamination by other cell types occurred,however, because all groups were treated similarly and the amount of contamination from small sensory neurons likely would be similar in all samples.

2.5.1 mRNA expression changes after SCI

In large DRG neurons, spinal transection had no effect on mRNA expression of neurotrophic factors or their receptors that were probed in this study (Figure 6). Heat shock protein mRNA expression for HSP-27 and -70 was also unaffected but transection did transiently increase the expression of Caspase-9 (Figure 6).

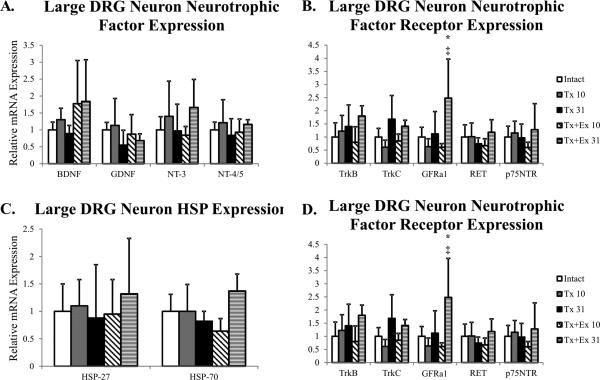

Figure 6.

Gene expression in large DRG neurons of intact, transected (Tx 10, Tx 31), and transected plus exercise (Tx+Ex 10, Tx+Ex 31) rats (n=6 for all groups). ± error is indicative of standard deviation. Grey background indicates expression of the gene is significantly altered in one of the injury-treatment groups. * indicates significantly different from intact; # indicates significantly different from Tx 10; † indicates significantly different from Tx 31; ‡ indicates significantly different from Tx+Ex 10.

2.5.2 mRNA expression changes due to cycling exercise following SCI

Unlike the motoneuron and intermediate grey matter response, exercise had no effect on neurotrophic factor mRNA expression in DRG neurons for any of the neurotrophic factors probed (Figure 6). However, exercise did result in a delayed increase in the expression of GFRα1, the GDNF receptor (Figure 6). HSP-27 and -70 mRNA expression was unaffected by exercise (Figure 6) but exercise decreased the expression of Caspase-3 and Caspase-7 and attenuated the transection induced increase of Caspase-9 (Figure 6). Surprisingly, at the later time point exercise increased mRNA expression of Caspase-3 and Caspase-9 (Figure 6).

3. Discussion

We investigated gene expression in whole cord and isolated motor and sensory neurons after SCI and cycling exercise to identify possible molecular mechanisms associated with activity-dependent plasticity. We measured changes over short (10d) and long term (31d) response periods with and without hindlimb exercise. Results indicate clear effects of passive cycling on expression of neurotrophic factors in cells of the motor system. We also demonstrate that different neuronal populations respond differently to transection injury and exercise.

In the whole cord it appeared that changes in expression of the caspases as well as the HSPs were primarily occurring in the white matter of the spinal cord since comparable changes were not observed in LMD grey matter sections. The caspases and HSPs displayed significant increases in expression in whole cord samples, with little if any change in motoneurons and intermediate grey matter. On the other hand, increases in neurotrophic factors and their receptors were found in both whole cord and the laser micro dissected samples; motoneurons and intermediate grey matter, suggesting them as a source for the increases observed in whole cord samples.

3.1 Response to Spinal Cord Injury

Changes in expression of neurotrophic factor mRNA and protein have been previously reported within the first few days following CNS trauma and spinal cord injury (Gulino et al., 2004; Hutchinson et al., 2004; Mattson and Scheff, 1994; Nakamura and Bregman, 2001). In contrast, we saw few changes in neurotrophic factor expression at 10 days in whole cord tissue. Comparisons between these experiments are difficult as different injury models and different time frames were used, nevertheless, work by Nakamura and Bregman (2001) and Gulino et al. (2004) show acute (at or less than 1 day after SCI) changes in neurotrophic factor expression followed by a return to normal levels by 1 week. Likewise, our data showed no change in LMD samples and little change with injury in whole cord samples at 10 days. Only GDNF showed an increase in protein level and the early, transient increase in NT-4 mRNA did not translate into increased protein. Because there is little change in neurotrophic factor expression, it suggests minimal potential for neurotrophic factor mediated changes in spinal circuitry at this early time point.

At 31 days, SCI resulted in an increase in levels of NT-3 protein expression which may indicate a role in injury related neuroplasticity. NT-3 over expression via viral vectors induces sprouting of supraspinal neurons (Zhou et al., 2003) and guides regenerating sensory axons across a lesion to form synapses (Alto et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2006). NT-3 also induces remyelination after brain or spinal cord injury (Jean et al., 2003; McTigue et al., 1998), and increases proliferation and maturation of oligodendrocytes (Barres et al., 1994; Heinrich et al., 1999) which express the TrkC receptor (Kumar et al., 1998), suggesting an effect in the spinal cord white matter.

Although there was little change in neurotrophic factors 10 days after injury, mRNA for TrkB and GFRα1 was increased, especially in whole cord and motoneuron samples. It is possible that this increase is a response to reduced BDNF, GDNF and NT-4 expression which may be limited by inactivity of hindlimb muscles, as neurotrophic factor expression in muscle is dependent on maintaining a minimal level of activity (Funakoshi et al., 1995).

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a family of related proteins responsible for diverse functions critical to cell survival. Primarily they act as protein chaperones, ensuring the proper folding of synthesized and misfolded proteins, but they also break up protein aggregates, bind to the nuclear matrix, transport proteins across membranes, and act as extracellular inflammatory signals (reviewed in Lindquist and Craig, 1988; Reddy et al., 2008). While HSPs are named for the thermal tolerance they provide to cells, recent studies have revealed protective roles for HSPs in neurons during stressful conditions, such as ischemia, microglial activation and apoptosis (Sun et al., 2006; Yenari et al., 2005). HSP mRNA increased in whole cord samples following injury, but this did not translate into an increase in protein. No increase in HSP mRNA was detected in any of the LMD motoneuron and intermediate grey matter samples. These samples reflect only grey matter mRNA expression of the spinal cord, suggesting that the increase in HSP mRNA in whole cord may reflect change in the white matter of the spinal cord. It is possible that because of ongoing apoptosis, oligodendrocytes and microglia in degenerating white matter are stressed and are upregulating the expression of heat shock proteins as previous experiments have demonstrated (Guzman-Lenis et al., 2008).

Apoptosis is a highly regulated, active form of cell death originally described during development, but which also is observed following injury to the nervous system. It can be triggered by cellular stress or loss of essential target derived factors and is mediated by the activation of a family of cystein proteases called caspases. Caspase activation involves cleavage of the pro-caspase form (zymogen) into subunits called heterodimers. These interact with another heterodimer to form a functionally active caspase molecule capable of initiating proteolysis and apoptosis (Wei et al., 2000; Renatus et al., 2001). Increases in caspase expression may be related to ongoing apoptosis occurring in the spinal cord (Springer et al., 1999; Emery et al., 1998) which can continue for weeks following the initial insult (Crowe et al., 1997; Shuman et al., 1997). Neuronal and glial apoptosis in the spinal cord would have negative consequences on plasticity by reducing the potential targets for the formation of new functional circuits and possibly limiting recovery. Here we measured changes in caspase expression, but did not attempt to quantify apoptotic cells found after SCI, thereby limiting the interpretation.

While the thoracic transection is several segments rostral to the lumbar enlargement tissue that was studied, we still found significant increases in the expression of mRNA for all three caspases tested in whole cord tissue and increased expression of protein for Caspase-7. Increased expression of the 32kd and 40kd isoforms, which likely represent the pro-caspase and ubiquitinated pro-caspase isoforms respectively, suggest that the increase is not leading to increased apoptosis. Neither of the cleaved subunits were identified by Western blot, essential for Caspase-7's apoptotic activity, and the pro-caspase isoform is being ubiquitinated, likely marking it for degradation.

Little change in laser micro dissected samples from the spinal cord (motoneurons and intermediate grey matter) was found. The finding that caspase mRNA and protein expression is increased in whole cord tissue, but not grey matter samples indicates that this, like the HSP expression, likely is primarily associated with the white matter. Axotomy of descending fibers and subsequent Wallerian degeneration are likely causes for this increase in expression of apoptotic mediators as there is apoptosis of oligodendrocytes and possibly microglia involved in clearing cellular debris at long distances after spinal cord injury (Shuman et al., 1997). However, without further assessment of the location of the HSP and Caspase expression via in situ hybridization or immunological visualization, it cannot be confirmed. We cannot exclude the possibility that apoptosis and cellular stress are taking place in the grey matter or ascending fibers. In this area, further experiments are warranted to provide a more accurate conclusion.

3.2 Activity Dependent Plasticity

Following SCI, repetitive activity has been shown to enhance functional recovery by normalizing hyperactive reflexes and increasing locomotor ability (Cha et al., 2007; Nothias et al., 2005; Skinner et al., 1996). Increased expression of neurotrophic factors (Gomez-Pinilla et al., 2001; Gulino et al., 2004; Macias et al., 2007; Sandrow-Feinberg et al., 2009) is one mechanism for this recovery. The neurotrophic factors we examined have previously been shown to be involved in neural circuit organization. Exogenous delivery of BDNF, NT-3, NT-4 and GDNF reduce axon retraction and enhance axonal regeneration (Bregman et al., 1997; Dolbeare and Houle, 2003; Nothias et al., 2005; Ye and Houle, 1997), such that increased expression may attract sprouting fibers and encourage synapse development (Jovanovic et al., 1996; Ledda et al., 2007; Wang et al., 1995). Injury had very little effect on the expression of neurotrophic factors in any of our samples, but exercise increased the expression of several neurotrophic factors in whole cord and captured motoneurons and intermediate grey matter.

Both BDNF and GDNF are involved in the formation and strengthening of synapses (Gomez-Pinilla et al., 2002; Jovanovic et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1995). A recent report indicates that synaptic modulation by BDNF occurs through normal neural activity by the post-synaptic neuron (Matsuda et al., 2009). Because motoneurons upregulate BDNF, it suggests strengthening of existing synapses or formation of new ones on these cells. Surprisingly, we did not observe any change in TrkB mRNA or protein expression with exercise in either whole cord or DRG neurons, but the increased BDNF may recruit TrkB receptors to the synapse to make existing TrkB receptors more effective. Experiments by Suzuki et al., (2004) demonstrated that BDNF could translocate TrkB receptors into lipid rafts and Ji et al., (2005) showed that a rise in cAMP levels could facilitate the movement of TrkB receptors into postsynaptic density. Activity of proprioceptive DRG neurons due to passive cycling could provide increases in cAMP necessary for TrkB translocation.

Likewise, GDNF can initiate presynaptic differentiation through signaling with its receptor, GFRα1 (Ledda et al., 2007). We observed an increase of GDNF mRNA expression in motoneurons and simultaneous increase in the expression of its receptor, GFRα1, in large DRG neurons. This indicates possible signaling between motoneurons and large DRG neurons which can initiate synaptogenesis. Numerous experiments have previously demonstrated increased sensory control over locomotion with training (Edgerton et al., 2004; Rossignol et al., 2006) and this implies a mechanism by which exercise can increase afferent control over motor output.

Exercise also affected expression of survival factors and caspases. In whole cord tissue we found that HSP mRNA was upregulated with injury but unaffected by exercise. However, exercise increased levels of both HSP-27 and HSP-70 protein. The discrepancy between transcription and translation could be due to several factors. The most likely explanation is RNA stabilization, which results in increased translation of protein without affecting mRNA transcription. In Drosophila, HSP-70 mRNA was stabilized and translated at high efficiency after stress stimulus, but rapidly degraded during recovery (Petersen and Lindquist, 1989). Stabilization of existing mRNA in exercised animals may account for the increase in protein levels without a concomitant increase in mRNA. Since we are unable to isolate sufficient protein from laser micro dissected samples, we cannot determine whether the absence of mRNA change in those samples masks changes in protein.

Interestingly, two caspases we tested were initially decreased with exercise, and then increased after a longer period of exercise. We observed an initial decrease in expression of Caspase-3 and -9 mRNA in large DRG neurons in spinal animals that received exercise for 1 week, but after four weeks of exercise, mRNA expression of caspases -3 and -9 was significantly elevated in exercised animals. This effect was also apparent in motoneurons, where caspase-3 mRNA expression was increased with four weeks of exercise. A growing body of literature suggests that caspase-3 is involved in synaptic plasticity in the central nervous system (reviewed in Gulyaeva, 2003; Gilman and Mattson, 2002). Numerous proteins involved in synaptic function and maintenance are substrates of caspase-3 and in vitro studies demonstrated the ability of caspase-3 to cleave GluR1 and suppress AMPA currents in rat hippocampal neurons (Lu et al., 2002). Other evidence suggests caspase-3 may be involved in learning. (Kudryashov et al., 2004) demonstrated suppression of long-term potentiation with a caspase-3 inhibitor in rat hippocampal slices and (Stepanichev et al., 2005) found that inhibition of caspase-3 by intraventricular injection impaired avoidance reactions in a model of active-avoidance learning (shuttle box). Another possibility is that release of pro-inflammatory cytokines with exercise (Ament and Verkerke, 2009; Ostrowski et al., 1999; Steensberg et al., 2000) is responsible for the increase in caspase expression. However, the ability of exercise to modify internal circuit arrangement (Cha et al., 2007; Nothias et al., 2005; Ollivier-Lanvin et al., 2010; Skinner et al., 1996) and decrease caspase expression supports the hypothesis that increased caspase-3 mRNA expression at these late time points is due to synaptic modifications and not apoptotic activity.

3.3 Issues of Sensitivity

In an experimental paradigm that measures relative changes in gene expression, it is important to address the issue of sensitivity. These issues are related to both techniques utilized and sample size. Both realtime PCR and Western blot are sensitive to changes in expression, but only assess relative amounts of the molecule probed. When examining very small sample amounts, such as mRNA from laser micro dissected samples, small differences in the amount of the molecule probed can result in larger relative differences. As such, large changes in relative expression of molecules should be viewed cautiously, particularly in groups that display large error. Our groups, which consisted of 6 animals apiece, were sufficiently strong to detect most differences in the molecules probed. However, due to the sensitivity of the test and relatively low group numbers, large inter-animal variation was evident in some probes. In such cases, the relative changes may be convincing, but should be viewed cautiously.

To address these issues, we have consciously made the choice to focus on the significance of the comparison as opposed to the changes in magnitude. First, we displayed error as predicted for the population (standard deviation) as opposed to the more generous standard error which represents the error for the groups. Second, we used a fairly stringent post-hoc analysis, Tukey's comparison. Third, we attempted to only discuss those changes found to be statistically significant. By taking these precautions, we are able to more confidently present these data and discuss their significance and impact on the injured spinal cord.

Although seemingly large differences in expression failed to exceed these more stringent standards, the increase of BDNF mRNA expression in motoneurons of Tx31 is significant when compared to motoneurons from intact animals when examined under the less stringent Fisher's LSD post-hoc analysis (p=0.015). Likewise, the comparisons of NT-4 mRNA; Intact to Tx+Ex10 (p=0.018) and Tx31 to Tx+Ex31 (p=0.009), were also found to be significant. Therefore, a strong argument can be made that the increase observed is real.

Conclusions

Passive cycling exercise following spinal cord injury has been shown to be beneficial to physiological and behavioral outcomes. Here we identified cellular sources and targets of neurotrophic factors, heat shock proteins and caspases that are affected by SCI and exercise. Cells associated with descending supraspinal input (motoneurons and intermediate grey matter) greatly increased production of BDNF and GDNF with exercise while sensory neurons exhibited very little change with SCI with or without exercise. We further showed that some of the responses following injury and exercise are transient while others persist throughout the testing period indicating temporal change in response characteristics. By identifying gene expression differences between cells of the sensory and motor systems, we can better understand the mechanisms by which exercise alters physiological and behavioral function in the spinal cord and begin to develop appropriate therapies to enhance recovery following SCI.

Due to the nature of the assays performed, it is difficult to determine a mechanism responsible for the changes in gene expression. However, we speculate that the proprioceptive stimulation provided by our exercise regimen is critical to these changes and likely due to the direct connection between proprioceptive sensory neurons and motoneurons. This is based on the previously published work that proprioceptive stimulation is critical for functional changes following complete SCI and this form of passive exercise (Ollivier-Lanvin et al., 2010) and our own unpublished observations that animals in which proprioceptive stimulation is impaired by dorsal root rhizotomy, fail to reflect the same changes following exercise in either BDNF or GDNF (unpublished results). Others have also reported the requirement of proprioceptive stimulation for the beneficial effects of exercise (Gomez-Pinilla et al., 2004). Further experiments into the nature of this relationship and the critical levels of exercise to promote plasticity have the potential to improve current therapies and the quality of living for patients living with SCI.

4. Methods

4.1 Animal Groups

30 adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (225-250g) were divided into 5 groups (n=6): Uninjured control (intact); injured for 10 days (Tx 10); injured for 31d (Tx 31); injured for 10d with cycling exercise (Tx+Ex 10); and injured for 31d with cycling exercise (Tx+Ex 31). All experiments were performed at Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia PA. The experimental protocol was approved by Drexel University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and animal use followed National Institute of Health (NIH) guidelines.

4.2 Spinal transection

Rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, confirmed by the absence of corneal reflexes and response to paw pinch. Under aseptic conditions the spinal cord was exposed by laminectomy of the ninth thoracic vertebra (T9). Meningeal membranes were opened longitudinally at the midline and a 2 mm length of T10 spinal cord was removed by gentle aspiration. The resulting lesion cavity was filled with gel foam to achieve hemostasis. Then the gel foam was removed, the dura was closed with 10-0 suture and the overlying muscles and fascia were closed in layers with sutures. The skin incision was closed with wound clips. After injury, bladders were manually expressed 2-3 times daily for approximately 2 weeks, until reflex voiding returned. Ampicillin (0.20 ml, 100 mg/kg) was administered twice daily for 7 days to prevent infection and sterile lactated Ringers Solution in 5% dextrose was provided daily (5 ml, sc) to prevent dehydration. Special absorbent bedding was provided to prevent pressure ulceration or other post operative complications.

4.3 Cycling Exercise

Details of this passive form of exercise have been provided previously (Houle et al., 1999; Skinner et al., 1996). In brief, animals were supported in an adjustable sling with their hindlimbs extending beneath them through openings in the sling. The hindpaws were secured to motor-driven foot pedals with surgical tape where movement of the foot was restricted to the ankle joint. Exercise began 5 days after spinal transection and continued on a daily basis, 5 days per week. There were two 30 minute exercise sessions, at a rate of 45 rpm, separated by a 10 minute rest period each day. Animals in the Tx+Ex 10 group received exercise for 5d consecutively, while animals in the Tx+Ex 31 group received exercise for a total of 20d over a 4 week period (Fig. 1A).

4.4 Tissue Collection

Animals in the exercised groups were sacrificed approximately 1 hour after their final training session. Animals in the injured but untrained groups were sacrificed on corresponding post-injury days. Animals received a lethal dose of Euthasol (390 mg/kg, J.A. Webster, Sterling, MA). Lumbar spinal cord segments L4-L6 were removed and divided longitudinally and then transversely into four blocks (Fig. 1B);1 block was used for isolation of total RNA, 1 block for isolation of mRNA from specific cell types captured by laser micro dissection (LMD) and 1 block for isolation of protein for Western blot analysis. The 4th block was kept in reserve if required as replacement for any of these procedures. L4-L6 spinal dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were harvested and processed for LMD of large sensory neurons. All tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for further processing.

4.5 Laser Micro Dissection and Quantitative PCR

For whole cord mRNA, one block of the L4-L6 spinal cord was homogenized in buffer RLT + 2-mercaptoethanol and total RNA was isolated with an RNEasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

For laser micro dissection one segment of spinal cord tissue or a whole dorsal root ganglion was sectioned at 20μm onto PEN foil slides (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and stored at -80°C. For staining, slides were individually equilibrated to -20°C and fixed in 75% EtOH at -20°C for 2min. Slides were washed in water for 30s, stained with toluidine blue for 30s and rinsed with water. Slides were dehydrated for 30s in 75% EtOH, and then in 95% EtOH. All solutions were made with DEPC treated water. Cells were isolated by laser micro dissection using a Leica AS LMD and stored in RNA stabilization buffer, RLT + 2-mercaptoethanol. Approximately 300 motoneurons, identified by their size and ventral position (Fig. 1C), were collected per animal. From the same slides intermediate grey matter, defined as the region encompassing laminae IV, V, VI and most of VII, was collected. Unlike the other LMD samples, the whole region was collected, as opposed to individual cells providing a mixture of neurons and glia. Large DRG cells were distinguished by their cross-sectional area (>1000μm). RNase/DNase free tubes containing micro dissected cells were stored at -80°C before RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated from laser micro dissected samples with an RNEasy plus Micro kit (QIAGEN) and cDNA was created from 100ng total RNA with an RT2 First Strand Kit (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD).

Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR)was conducted with a MyiQ Real Time Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Setup for the Q-PCR reaction was as follows: each 25μL reaction contained 12.5μL of iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), 1.5μL of forward (4μM) and reverse (4μM) primers, 1μL of cDNA, and 8.5μL of DEPC water. All samples were run in duplicate and crossing thresholds were averaged for each animal. A list of primers and their sequence is provided in Table 1. Data were analyzed by software supplied with the MyiQ system which uses a modified 2-ΔΔCT method described by Vandersomple et al., (2002). This method finds the geometric mean of multiple control genes for more accurate assessments of basal RNA concentration. Differences in the geometric average of the control genes are subtracted from differences in target gene RNA levels to find true differences in expression. All quantitative PCR data was normalized to the mRNA expression of two housekeeping genes; GAPDH and 18sRNA.

Table 1.

Primer Design

| Gene / Nucleotide Ref # | Forward Primer Sequence | Start | Backward Primer Sequence | Start | Product Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurotrophic Factors | BDNF/ NM_012513.3 | gtc ccc cag gtc act ctt c | 2188 | gga gga ggg agg gaa aga a | 2283 | 96 |

| GDNF/ NM_019130.1 | agg gaa agg tcg cag agg | 361 | cag ttc ctc ctt ggt ttc gt | 469 | 109 | |

| NT-3 / NM_031073.2 | gat cca ggc gga tat ctt ga | 114 | gat cca ggc gga tat ctt ga | 258 | 145 | |

| NT-4 / NM_013184.1 | aga gtg agg agg tgg agg tg | 165 | gga gga gga gaa gga aaa gg | 255 | 91 | |

| Neurotrophic Factor Receptors | TrkB / NM_012731.1 | tct cat ttt agg ccg ctt tg | 4470 | gag ttt gag gtg ggt gaa g | 4587 | 118 |

| TrkC / NM_019248.1 | tcc tct cct cct cct cct ct | 10 | caa gaa aat ccg cca gaa ac | 102 | 93 | |

| GFRa1 / NM_012959.1 | tct gta aat ggt tgc gtc ct | 3224 | ctc tgt ggg agg gtg aga ag | 3334 | 111 | |

| RET / NM_012643.1 | ggt tta gct tca agg gct ga | 4731 | cgg aac aga cag aca aat gg | 4824 | 94 | |

| p-75 / NM_012610.1 | gcg ggt ggt att ttt atg ga | 2942 | aga gac ccc cag aac caa ac | 3091 | 150 | |

| Heat Shock Proteins | HSP-27 / NM_031970.3 | acg aag aaa ggc agg atg aa | 444 | ggg aca ggg aag agg aca c | 548 | 105 |

| HSP-70 / NM_212504.1 | ctc ctg tat ctg cct ctc caa | 5479 | tcg tct tct cca tca cca ga | 5593 | 115 | |

| Caspases and GFAP | Caspase-3 / NM_012922.2 | gga cct gtg gac ctg aaa aa | 450 | agt ttc ggc ttt cca gtc ag | 526 | 78 |

| Caspase-7 / NM_022260.2 | gcc tct gaa gag gac cac ag | 278 | gcc tct gaa gag gac cac ag | 467 | 90 | |

| Caspase-9 / NM_031632.1 | atg gtg gag gtg aag aac ga | 761 | aga gag gat gac cac cac ga | 871 | 111 | |

| GFAP / NM_017009.1 | ccc cat tcc ctt tct tat gc | 2369 | ata cga agg cac tcc aca cc | 2484 | 116 | |

4.6 Immunoblotting Analysis

Protease inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and the phosphatase inhibitor, 10mM phenyl-methyl sulphonyl-fluoride (PMSF, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were added to extraction buffer (100mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, 750mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 1% BSA, 2% Triton). Samples were homogenized by sonication and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4°C for 30 min. Supernatant was removed and stored at -80°C. Standard Laemmli buffer was added before samples were boiled for 5 min. Equal amounts of protein were resolved in a 10%/16% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (BioRad) overnight. For most assays, membranes were blocked with 5% milk for 1 hour before incubation with primary antibody, but for phosphorylated TrkB, a 5% BSA block was used. Membranes were incubated overnight in primary antibody at 4°C before incubation with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1hr at room temperature. Specifications for primary and secondary antibodies are listed in table 1. Membranes were washed and visualized using Western Lightning ECL (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and Blue basic autorad film (ISC Bio Express, Kaysville, UT). To avoid overlapping patterns of immunoreactivity, blots were stripped for 30 min between incubations in 65mM Tris buffer, pH 6.8, containing 1% SDS (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Finally, membranes were probed with mouse monoclonal anti-actin antibody to ensure that comparable levels of protein were loaded into each lane. Optical densities of immunopositive bands were analyzed using GeneSnap and GeneTools (both from Syngene, Frederick, MD) and normalized to actin bands detected for each sample.

Due to limited amounts of protein, not all genes examined for mRNA have corresponding protein data. Decisions to include data were based on mRNA results and specificity of antibodies.

4.7 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with PASW Statistics v.17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). ANOVA was used to determine whether a significant interaction was present among groups. Positive results were followed up with Tukey's post-hoc test with an alpha of less than 0.05 considered significant.

Highlights.

Motor and sensory neurons displayed distinct responses to injury and exercise

Transection injury increased lumbar expression of TrkB, caspases, and HSPs

Exercise increased motoneuron expression of neurotrophic factors

Neurotrophic factor expression was unaffected by exercise in large DRG neurons

Acute exercise decreased caspase expression in motoneurons and large DRG neurons

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grant NS 055976. We gratefully acknowledge Kassi N. Miller for postoperative care and bicycle training of animals and Lauren Santi for assistance with tissue preparation and laser micro dissection in this study.

Abbreviations

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DRG

Dorsal root ganglion

- Ex

Exercise

- GDNF

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HSP

Heat shock protein

- LMD

Laser micro dissection

- NT-3

Neurotrophin-3

- NT-4

Neurotrophin-4

- SCI

Spinal cord injury

- Tx

Transection

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alto LT, Havton LA, Conner JM, Hollis Ii ER, Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Chemotropic guidance facilitates axonal regeneration and synapse formation after spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1106–13. doi: 10.1038/nn.2365. DOI: nn.2365 [pii] 10.1038/nn.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ament W, Verkerke GJ. Exercise and fatigue. Sports Med. 2009;39:389–422. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939050-00005. DOI: 00007256-200939050-00005 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astorino TA, Tyerman N, Wong K, Harness E. Efficacy of a new rehabilitative device for individuals with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31:586–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres BA, Raff MC, Gaese F, Bartke I, Dechant G, Barde YA. A crucial role for neurotrophin-3 in oligodendrocyte development. Nature. 1994;367:371–5. doi: 10.1038/367371a0. DOI: 10.1038/367371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont E, Houle JD, Peterson CA, Gardiner PF. Passive exercise and fetal spinal cord transplant both help to restore motoneuronal properties after spinal cord transection in rats. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29:234–42. doi: 10.1002/mus.10539. DOI: 10.1002/mus.10539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman BS, McAtee M, Dai HN, Kuhn PL. Neurotrophic factors increase axonal growth after spinal cord injury and transplantation in the adult rat. Exp Neurol. 1997;148:475–94. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha J, Heng C, Reinkensmeyer DJ, Roy RR, Edgerton VR, De Leon RD. Locomotor ability in spinal rats is dependent on the amount of activity imposed on the hindlimbs during treadmill training. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1000–12. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté M-P, Azzam GA, Lemay MA, Zhukareva V, Houle JD. Activity-dependent increase in neurotrophic factors is associated with an enhanced modulation of spinal reflexes after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:299–309. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe MJ, Bresnahan JC, Shuman SL, Masters JN, Beattie MS. Apoptosis and delayed degeneration after spinal cord injury in rats and monkeys. Nat Med. 1997;3:73–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon RD, Hodgson JA, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Locomotor capacity attributable to step training versus spontaneous recovery after spinalization in adult cats. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1329–40. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leon RD, Hodgson JA, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Retention of hindlimb stepping ability in adult spinal cats after the cessation of step training. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:85–94. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolbeare D, Houle JD. Restriction of axonal retraction and promotion of axonal regeneration by chronically injured neurons after intraspinal treatment with glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF). J Neurotrauma. 2003;20:1251–61. doi: 10.1089/089771503770802916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont-Versteegden EE, Houle JD, Gurley CM, Peterson CA. Early changes in muscle fiber size and gene expression in response to spinal cord transection and exercise. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C1124–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.4.C1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton VR, Roy RR. Robotic training and spinal cord plasticity. Brain Res Bull. 2009;78:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.09.018. DOI: S0361-9230(08)00336-5 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton VR, Tillakaratne NJ, Bigbee AJ, de Leon RD, Roy RR. Plasticity of the spinal neural circuitry after injury. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:145–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144308. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery E, Aldana P, Bunge MB, Puckett W, Srinivasan A, Keane RW, Bethea J, Levi AD. Apoptosis after traumatic human spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:911–20. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.0911. DOI: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi H, Belluardo N, Arenas E, Yamamoto Y, Casabona A, Persson H, Ibanez CF. Muscle-derived neurotrophin-4 as an activity-dependent trophic signal for adult motor neurons. Science. 1995;268:1495–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7770776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman CP, Mattson MP. Do apoptotic mechanisms regulate synaptic plasticity and growth-cone motility? Neuromolecular Med. 2002;2:197–214. doi: 10.1385/NMM:2:2:197. DOI: NMM:2:2:197 [pii] 10.1385/NMM:2:2:197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Pinilla F, Ying Z, Opazo P, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Differential regulation by exercise of BDNF and NT-3 in rat spinal cord and skeletal muscle. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1078–84. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Pinilla F, Ying Z, Roy RR, Molteni R, Edgerton VR. Voluntary exercise induces a BDNF-mediated mechanism that promotes neuroplasticity. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2187–95. doi: 10.1152/jn.00152.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Pinilla F, Ying Z, Roy RR, Hodgson J, Edgerton VR. Afferent input modulates neurotrophins and synaptic plasticity in the spinal cord. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3423–32. doi: 10.1152/jn.00432.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulino R, Lombardo SA, Casabona A, Leanza G, Perciavalle V. Levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-4 in lumbar motoneurons after low-thoracic spinal cord hemisection. Brain Res. 2004;1013:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.055. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.055 S0006899304005591 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulyaeva NV. Non-apoptotic functions of caspase-3 in nervous tissue. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2003;68:1171–80. doi: 10.1023/b:biry.0000009130.62944.35. DOI: BCM68111459 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Lenis MS, Vallejo C, Navarro X, Casas C. Analysis of FK506-mediated protection in an organotypic model of spinal cord damage: heat shock protein 70 levels are modulated in microglial cells. Neuroscience. 2008;155:104–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.078. DOI: S0306-4522(08)00653-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich M, Gorath M, Richter-Landsberg C. Neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) modulates early differentiation of oligodendrocytes in rat brain cortical cultures. Glia. 1999;28:244–55. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199912)28:3<244::AID-GLIA8>3.0.CO;2-W [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle JD, Morris K, Skinner RD, Garcia-Rill E, Peterson CA. Effects of fetal spinal cord tissue transplants and cycling exercise on the soleus muscle in spinalized rats. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:846–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199907)22:7<846::aid-mus6>3.0.co;2-i. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199907)22:7<846::AID-MUS6>3.0.CO;2-I [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson KJ, Gomez-Pinilla F, Crowe MJ, Ying Z, Basso DM. Three exercise paradigms differentially improve sensory recovery after spinal cord contusion in rats. Brain. 2004;127:1403–14. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh160. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awh160 awh160 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean I, Lavialle C, Barthelaix-Pouplard A, Fressinaud C. Neurotrophin-3 specifically increases mature oligodendrocyte population and enhances remyelination after chemical demyelination of adult rat CNS. Brain Res. 2003;972:110–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02510-1. DOI: S0006899303025101 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Pang PT, Feng L, Lu B. Cyclic AMP controls BDNF-induced TrkB phosphorylation and dendritic spine formation in mature hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:164–72. doi: 10.1038/nn1381. DOI: nn1381 [pii] 10.1038/nn1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic JN, Benfenati F, Siow YL, Sihra TS, Sanghera JS, Pelech SL, Greengard P, Czernik AJ. Neurotrophins stimulate phosphorylation of synapsin I by MAP kinase and regulate synapsin I-actin interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3679–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudryashov IE, Yakovlev AA, Kudryashova IV, Gulyaeva NV. Inhibition of caspase-3 blocks long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2004;34:877–80. doi: 10.1023/b:neab.0000042571.86110.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Kahn MA, Dinh L, de Vellis J. NT-3-mediated TrkC receptor activation promotes proliferation and cell survival of rodent progenitor oligodendrocyte cells in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54:754–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981215)54:6<754::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-K. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981215)54:6<754::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-K [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledda F, Paratcha G, Sandoval-Guzman T, Ibanez CF. GDNF and GFRalpha1 promote formation of neuronal synapses by ligand-induced cell adhesion. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:293–300. doi: 10.1038/nn1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S, Craig EA. The heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:631–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003215. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Keeler BE, Zhukareva V, Houle JD. Cycling exercise affects the expression of apoptosis-associated microRNAs after spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2010;226:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovely RG, Gregor RJ, Roy RR, Edgerton VR. Effects of training on the recovery of full-weight-bearing stepping in the adult spinal cat. Exp Neurol. 1986;92:421–35. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90094-4. DOI: 0014-4886(86)90094-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Fu W, Salvesen GS, Mattson MP. Direct cleavage of AMPA receptor subunit GluR1 and suppression of AMPA currents by caspase-3: implications for synaptic plasticity and excitotoxic neuronal death. Neuromolecular Med. 2002;1:69–79. doi: 10.1385/NMM:1:1:69. DOI: NMM:1:1:69 [pii] 10.1385/NMM:1:1:69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias M, Dwornik A, Ziemlinska E, Fehr S, Schachner M, Czarkowska-Bauch J, Skup M. Locomotor exercise alters expression of pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor TrkB in the spinal cord of adult rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:2425–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05498.x. DOI: EJN5498 [pii] 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda N, Lu H, Fukata Y, Noritake J, Gao H, Mukherjee S, Nemoto T, Fukata M, Poo MM. Differential activity-dependent secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from axon and dendrite. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14185–98. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1863-09.2009. DOI: 29/45/14185 [pii] 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1863-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Scheff SW. Endogenous neuroprotection factors and traumatic brain injury: mechanisms of action and implications for therapy. J Neurotrauma. 1994;11:3–33. doi: 10.1089/neu.1994.11.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTigue DM, Horner PJ, Stokes BT, Gage FH. Neurotrophin-3 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor induce oligodendrocyte proliferation and myelination of regenerating axons in the contused adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5354–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05354.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Bregman BS. Differences in neurotrophic factor gene expression profiles between neonate and adult rat spinal cord after injury. Exp Neurol. 2001;169:407–15. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7670. DOI: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7670 S0014-4886(01)97670-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothias JM, Mitsui T, Shumsky JS, Fischer I, Antonacci MD, Murray M. Combined effects of neurotrophin secreting transplants, exercise, and serotonergic drug challenge improve function in spinal rats. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2005;19:296–312. doi: 10.1177/1545968305281209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollivier-Lanvin K, Keeler BE, Siegfried R, Houle JD, Lemay MA. Proprioceptive neuropathy affects normalization of the H-reflex by exercise after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2010;221:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.10.023. DOI: S0014-4886(09)00455-5 [pii] 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski K, Rohde T, Asp S, Schjerling P, Pedersen BK. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine balance in strenuous exercise in humans. J Physiol. 1999;515(Pt 1):287–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.287ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RB, Lindquist S. Regulation of HSP70 synthesis by messenger RNA degradation. Cell Regul. 1989;1:135–49. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phadke CP, Flynn SM, Thompson FJ, Behrman AL, Trimble MH, Kukulka CG. Comparison of single bout effects of bicycle training versus locomotor training on paired reflex depression of the soleus H-reflex after motor incomplete spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1218–28. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.022. DOI: S0003-9993(09)00220-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SJ, La Marca F, Park P. The role of heat shock proteins in spinal cord injury. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:E4. doi: 10.3171/FOC.2008.25.11.E4. DOI: 10.3171/FOC.2008.25.11.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renatus M, Stennicke HR, Scott FL, Liddington RC, Salvesen GS. Dimer formation drives the activation of the cell death protease caspase 9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14250–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231465798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol S, Dubuc R, Gossard JP. Dynamic sensorimotor interactions in locomotion. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:89–154. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2005. DOI: 86/1/89 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandrow-Feinberg HR, Izzi J, Shumsky JS, Zhukareva V, Houle JD. Forced exercise as a rehabilitation strategy after unilateral cervical spinal cord contusion injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:721–31. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0750. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2008.0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman SL, Bresnahan JC, Beattie MS. Apoptosis of microglia and oligodendrocytes after spinal cord contusion in rats. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:798–808. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971201)50:5<798::AID-JNR16>3.0.CO;2-Y. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971201)50:5<798::AID-JNR16>3.0.CO;2-Y [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner RD, Houle JD, Reese NB, Berry CL, Garcia-Rill E. Effects of exercise and fetal spinal cord implants on the H-reflex in chronically spinalized adult rats. Brain Res. 1996;729:127–31. DOI: 0006-8993(96)00556-2 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer JE, Azbill RD, Knapp PE. Activation of the caspase-3 apoptotic cascade in traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 1999;5:943–6. doi: 10.1038/11387. DOI: 10.1038/11387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensberg A, van Hall G, Osada T, Sacchetti M, Saltin B, Klarlund Pedersen B. Production of interleukin-6 in contracting human skeletal muscles can account for the exercise-induced increase in plasma interleukin-6. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 1):237–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00237.x. DOI: PHY_11483 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanichev MY, Kudryashova IV, Yakovlev AA, Onufriev MV, Khaspekov LG, Lyzhin AA, Lazareva NA, Gulyaeva NV. Central administration of a caspase inhibitor impairs shuttle-box performance in rats. Neuroscience. 2005;136:579–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.010. DOI: S0306-4522(05)00864-X [pii] 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Ouyang YB, Xu L, Chow AM, Anderson R, Hecker JG, Giffard RG. The carboxyl-terminal domain of inducible Hsp70 protects from ischemic injury in vivo and in vitro. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:937–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600246. DOI: 9600246 [pii] 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Numakawa T, Shimazu K, Koshimizu H, Hara T, Hatanaka H, Mei L, Lu B, Kojima M. BDNF-induced recruitment of TrkB receptor into neuronal lipid rafts: roles in synaptic modulation. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1205–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404106. DOI: jcb.200404106 [pii] 10.1083/jcb.200404106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L, Jones L, Tuszynski MH, Blesch A. Neurotrophin-3 gradients established by lentiviral gene delivery promote short-distance axonal bridging beyond cellular grafts in the injured spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9713–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0734-06.2006. DOI: 26/38/9713 [pii] 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0734-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Xie K, Lu B. Neurotrophins promote maturation of developing neuromuscular synapses. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4796–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Fox T, Chambers SP, Sintchak J, Coll JT, Golec JM, Swenson L, Wilson KP, Charifson PS. The structures of caspases-1, -3, -7 and -8 reveal the basis for substrate and inhibitor selectivity. Chem Biol. 2000;7:423–32. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye JH, Houle JD. Treatment of the chronically injured spinal cord with neurotrophic factors can promote axonal regeneration from supraspinal neurons. Exp Neurol. 1997;143:70–81. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.6353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yenari MA, Liu J, Zheng Z, Vexler ZS, Lee JE, Giffard RG. Antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory mechanisms of heat-shock protein protection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1053:74–83. doi: 10.1196/annals.1344.007. DOI: 1053/1/74 [pii] 10.1196/annals.1344.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Baumgartner BJ, Hill-Felberg SJ, McGowen LR, Shine HD. Neurotrophin-3 expressed in situ induces axonal plasticity in the adult injured spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1424–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01424.2003. DOI: 23/4/1424 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]