Abstract

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of reproductive cancer death in U.S. women. This high mortality rate is due to the lack of early detection methods and ineffectiveness of therapy for advanced disease. Until more effective screening methods and therapies are developed, chemoprevention strategies are warranted. The hen has a high spontaneous prevalence of ovarian cancer and has been used as a model for studying ovarian cancer chemoprevention. In this study, we used the hen to determine the effect of progestin alone, estrogen alone, or progestin and estrogen in combination (as found in oral contraceptives) on ovarian cancer prevalence. We found that treatment with progestin alone and in combination with estrogen decreased the prevalence of ovarian cancer. A significant risk reduction of 91% was observed in the group treated with progestin alone (risk ratio 0.0909: 95% confidence interval 0.0117-0.704) and an 81% reduction was observed in the group treated with progestin plus estrogen (risk ratio 0.1916: 95% confidence interval 0.043-0.864). Egg production was also significantly reduced in these treatment groups compared to control. We found no effect of progestin, either alone or in combination with estrogen, on apoptosis or proliferation in the ovary, indicating that this is not the likely mechanism responsible for the protective effect of progestin in the hen. Our results support the use of oral contraceptives to prevent ovarian cancer and suggest that ovulation is related to the risk of ovarian cancer in hens and that other factors, such as hormones, more than likely modify this risk.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, animal models of cancer, hen, oral contraceptives, ovulation

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of reproductive cancer death in U.S. women. This high mortality rate can be attributed to the fact that greater than 80% of women with the disease are diagnosed at late stages when tumors have metastasized. The 5-year survival rate is less than 30% for later stages of the disease, although the survival rate is greater than 90% for the ~15% of women diagnosed at earlier stages of the disease when the tumor is still confined to the ovary [1]. These data support the need for the development of early detection strategies for the disease. Unfortunately, efforts to identify a widely acceptable screening strategy have thus far failed and so cancer prevention remains the most viable method to limit development of fatal ovarian neoplasms. Chemopreventive agents, such as oral contraceptives, may act to protect women from the development of ovarian cancer.

Epidemiologic studies have consistently shown that ovarian cancer risk is decreased in women who use oral contraceptives [2]. In fact, a recent study showed that oral contraceptive use is associated with a 20% decrease in relative risk of ovarian cancer for every 5 years of use and longer duration of use further decreases the risk [3]. Additionally, the risk is reduced for 30 years or more after use has stopped [3]. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how oral contraceptives decrease the risk of ovarian cancer, including inhibition of ovulation, induction of apoptosis, and inhibition of proliferation [4]. Animal models can be used to test the efficacy and mechanism of action of chemopreventive agents.

Previous studies have used the domestic hen (Gallus domesticus) as a model of ovarian cancer. Like humans, the hen spontaneously develops aggressive ovarian cancers and the incidence increases with age [5]. Previous studies have shown that chicken ovarian tumors express antigens that are frequently expressed in human ovarian cancer as well as those that are useful as surrogate biomarker endpoints in chemoprevention trials [6]. Hens have also been used in studies testing the efficacy of putative chemopreventive agents including aspirin [7] and flaxseed [8] in preventing ovarian cancers. One promising study determined that treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera), a common constituent used in progestin-only formulations of contraceptives, resulted in a 15% reduction of risk of ovarian cancer in treated hens compared to control hens [9].

Our objective was to compare the efficacy of progestin (P), estrogen (E), and progestin and estrogen in combination (P+E) in preventing ovarian cancer in the hen. These hormones are commonly delivered together in commercially available human contraceptives. In order to determine a possible mechanism by which the hormones might prevent cancer, we examined how the treatments affected apoptosis and cellular proliferation in normal hen ovaries. Our results suggest that ovulation is related to the prevalence of ovarian cancer and the effect of ovulation may be separate from the effects of steroid hormones.

Materials and Methods

Animals

A total of 231, approximately one year-old single-comb White leghorn hens were randomly divided into four treatment groups. All birds were individually caged with access to food and water ad libitum and maintained on a 15h light and 9h dark schedule. Treatment groups consisted of: control (n=59), progestin and estrogen treatment combined (P+E; n=56), progestin alone (P; n=59), and estrogen alone (E; n=57). Hens were treated as described below. Egg production was monitored daily as a marker of ovulation and hens were weighed monthly. Necropsies were performed on hens that died before the termination of the experiment (n=71) as well as those that were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation at the end of the experiment (n=160). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cornell University.

Treatments

Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the treatment scheme. Hens in the control group were injected with 1 ml of the sesame oil vehicle, and implanted with an empty silastic tube. Hens in the P+E treatment group were injected with 50 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Spectrum Chemical, Gardena, CA) dissolved in 1 ml of sesame oil and implanted with 25 mg estradiol implants (Compudose 200; Elanco Animal Health, Indianapolis, IN) previously reported to be bioactive in the hen [10,11]. Hens in the P treatment group were injected with MPA as described above and implanted with an empty silastic tube. Finally, hens in the E treatment group were injected with 1 ml of sesame oil and implanted with estradiol implants as described above.

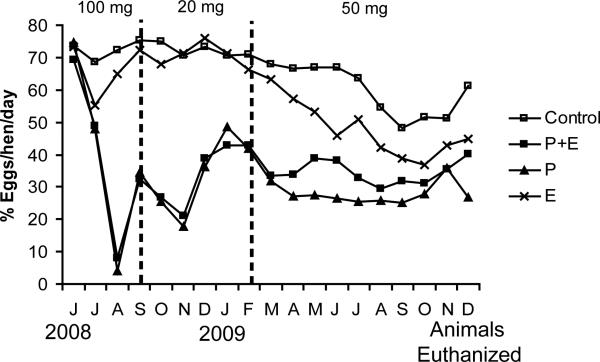

Injections of either sesame oil or MPA were administered into the breast muscle (i.m) every 3-4 weeks throughout the treatment period. Initially, the hens were injected with 100 mg as previously described [9] resulting in an almost complete cessation of egg production; however, due to adverse effects, the dose was reduced to 20 mg. Unfortunately, 20 mg was not sufficient to suppress ovulation long-term and, as a result, after approximately 8 months, the hens were injected with 50 mg which was maintained throughout the experiment. Compared to 100 mg, this dose was better tolerated and yet still reduced egg production (although to a lesser extent).

For implantation of the silastic tube or estradiol implant, hens were administered a local anesthetic (bupivicane; 5 mg/ml) between the wings where implants were inserted through an incision made with a scalpel. The incision was closed using tissue adhesive (VetBond). A second implant was inserted in the same location 180 days after the first implant to ensure estradiol levels were elevated throughout the treatment period. Treatments were administered for a total of 16 months similar to the previous study where progestin was administered to hens [9].

Tissue collection

Hens that died during the course of the experiment (n=71) or were terminated at the end of the experiment received a full necropsy. Tumors in hens were identified grossly by the presence of firm, nodular outgrowths on the ovary, often accompanied by ascites and implants on the serosa of tissues within the abdominal cavity as described previously [5, 12-14]. Sections of ovary were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed for histopathology by the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine Histopathology Laboratory. Slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined by two independent observers, one of whom is a board certified veterinary pathologist (ELB). Ovarian neoplasms were verified based on histology. Ovarian tumors identified in hens were staged based on gross examination as previously described [7, 15]. Briefly, stage 1 tumors are restricted to the ovary and only detectable by histology. Stage 2 tumors are restricted to the ovary and observable at necropsy. Stage 3 and stage 4 tumors have abdominal seeding without or with ascites, respectively.

Immunofluorescence

Paraffin sections of ovary were deparaffinized and rehydrated, followed by antigen retrieval by boiling in sodium citrate buffer for 20 minutes. Sections were blocked in PBS with 5% non-fat dry milk plus 10% goat serum and incubated with mouse anti-chicken ovalbumin (A6075; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 115 ug/ml overnight at 4°. Control slides were incubated with mouse IgG. Detection was achieved by incubating with AlexaFlour 488 goat anti-mouse IgG at 1 ug/ml (A-11001; Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hr at 39°. Slides were viewed using a Nikon eclipse E600 and pictures were taken with a Spot RT Slider camera. Images were taken at 3 s exposure.

Estradiol radioimmunoassay (RIA)

Blood samples were collected from the wing vein of a subset of hens throughout the experiment at 30, 60, 120, 180, and 360 days after the implantation of the first estradiol or control implants. Plasma isolated from the blood samples was assayed for estradiol using the Coat-A-Count estradiol RIA kit (Siemens, Los Angeles, CA). All samples were assayed in duplicate. The average intra-assay coefficient of variation was 22%.

TUNEL assay

Serial sections of ovarian tissue from a subset of the animals without cancer in each treatment group (n=6 per group) were analyzed for relative amounts of cellular apoptosis in the surface epithelium and within the follicular wall. Apoptosis was assessed using the ApopTag® Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Chemicon International, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Slides were scanned at 40X using the Aperio Scanscope (Aperio Inc., Vista, CA). Twenty random images of ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) and thirty random images of the stroma for each hen were obtained using the ImageScope Viewer program (Aperio Inc., Vista, CA). Positive staining of apoptotic nuclei was quantified in the images using the color range function of Adobe Photoshop. The intensity of positive staining was then graded on a scale from 0 to 3 (0=no staining; 1=low, 2=medium and 3=high intensity staining).

Proliferation assay

Serial sections from normal hens in each treatment group (n=6) were analyzed for proliferation by assessing expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) protein by immunofluorescence. For this procedure, deparaffinized sections were rehydrated through a series of incubations with xylene and ethanol. Sections were boiled in citrate buffer for antigen retrieval, blocked in 10% goat serum in PBS for 30 minutes at 37° and then incubated with a mouse anti-rat PCNA antibody previously validated in the chicken (PC-10; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA) at a dilution of 1:50 for 1 hr at 37° [16]. Control slides were incubated with mouse IgG. This was followed by incubation with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody for 1 hr at 37°. Slides were viewed using a Nikon eclipse E600 and six random images of OSE and the stroma for each hen were obtained at 20X magnification. PCNA positive nuclei were identified in the images using the color range function of Adobe Photoshop and the intensity of positive staining was graded on a scale from 0 to 3 (0=no staining; 1=low, 2=medium and 3=high intensity staining).

Statistical analysis

All tests were carried out using SAS version 9.2 with a significance level of p<0.05. The effect of treatment on ovarian cancer incidence was analyzed using proc GENMOD as recommended by staff at the Cornell Statistical Consulting Unit. Egg production and plasma estradiol level among treatments were analyzed using proc MIXED. The effects of treatment on apoptosis and proliferation in the OSE and the stroma were analyzed using proc GLM.

Results

Effect of treatment on cancer prevalence and stage

We observed a significant effect of treatment on the prevalence of ovarian cancer (p<0.01; Table 1). Nineteen percent of the hens in the control treatment group were diagnosed with ovarian cancer. This is similar to the percentages previously reported (10-23%) in hens at this age [7, 17]. Treatment with P alone (p<0.005) and P+E (p<0.01) significantly decreased prevalence of ovarian cancer compared to the control treatment, while administration of E alone had no significant effect.

Table 1.

Prevalence of ovarian cancer among treatments.

| Treatment | Total hens | Hens diagnosed with cancer (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 59 | 11 (19) |

| P+E | 56 | 2 (4)a |

| P | 59 | 1 (2)b |

| E | 57 | 11 (19) |

Decreased prevalence compared to control (p<0.01)

Decreased prevalence compared to control (p<0.005)

Based on gross evaluation, we found no significant effect of treatment on stage of ovarian cancer (Table 2), and the majority of the tumors were late stage (metastases present outside of the ovary, with or without ascites). Four tumors (all in the control group) were identified as early stage after examination of the H&E stained section. At necropsy, these ovaries had no visible signs of cancer, and two out of the four ovaries were regressed (no large or small yellow follicles present).

Table 2.

Stage of ovarian cancer [7] for hens diagnosed with the disease.

| Treatment | Stage 1 (%) | Stage 2 (%) | Stage 3 (%) | Stage 4 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4 (36) | 0 (0) | 4 (36) | 3 (27) |

| P+E | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

| P | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| E | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (45) | 6 (55) |

Treatment associated mortality

A total of 71 out of the original 231 (31%) birds died before experiment termination (Supplementary Table 2). Out of the birds that died, a larger proportion of hens treated with P alone (37%) or P+E (34%) died compared to the control (22%) or E alone (30%) groups, however, we found no statistically significant effect of treatment on mortality. The higher mortality in the hens treated with MPA may be due to the fact that a higher dose of MPA (100 mg) was utilized at the beginning of the experiment, because decreasing the dose resulted in less mortality. The higher dose was also used in the Barnes et al study (2002) and they reported a higher mortality rate for hens treated with MPA (32%) compared to the control treatment [9]. The mechanism of this effect is unclear; however, MPA treatment can result in polyuria, weight gain, liver damage and diabetes in birds [18]. We also observed no significant effect of treatment on body weight (data not shown).

Histological classification of ovarian tumors

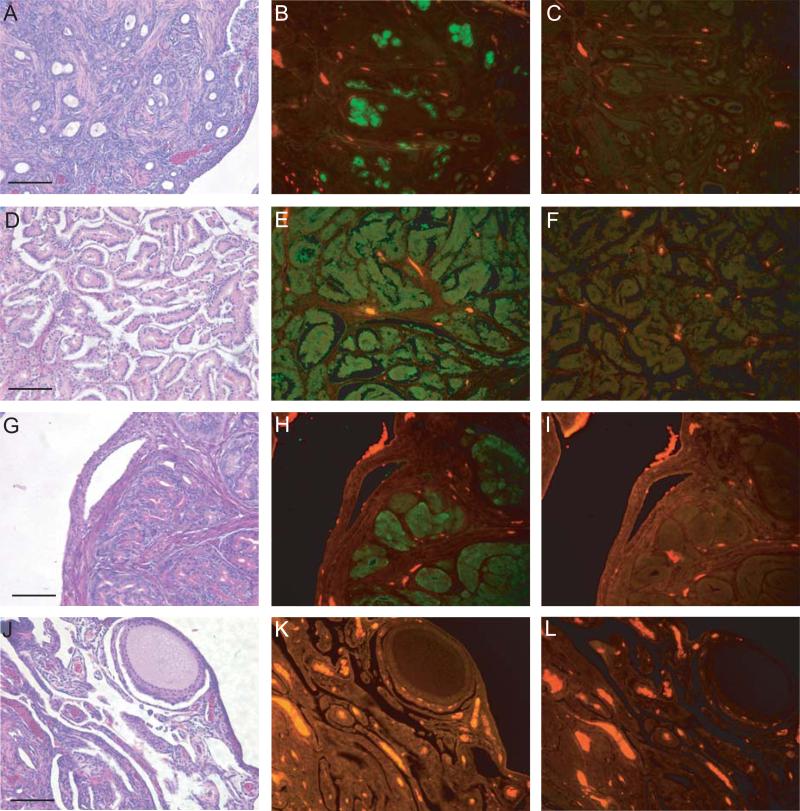

Microscopically, we identified three separate morphologies of the ovarian tumors: endometrioid, serous, and oviduct-like. Figure 1 illustrates examples of all three types. The endometrioid tumors resemble a type found in women, and are generally solid with a dense stromal component. They can exhibit glands (Figure 1A), as well as squamous differentiation and are positive for ovalbumin (Figure 1B), a known marker for chicken ovarian tumors [15, 19]. Note the lack of staining in the IgG control (Figure 1C). The serous tumors (Figure 1D) also resemble a type found in women and have very little stroma associated with the tumor cells (compared to endometrioid tumors) and also express ovalbumin (Figure 1E). These tumors can have papillary projections. Again, the IgG control is negative (Figure 1F). The third type, oviduct-like, does not have a tumor counterpart in women. These tumors are associated with the production of secretory granules (Figure 1G), resemble the oviduct in the chicken, express ovalbumin as well (Figure 1H), and the IgG control is negative (Fig. 1I). They may represent a subtype of the other two main types, but that is not clear at this time. As expected, normal ovary (Figure 1J) does not express ovalbumin (Figure 1K) and the IgG control is negative (Figure 1L). In hens treated with progestin, either alone or in combination with estrogen, we found no “oviduct” type of tumors (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence with antibodies against ovalbumin in chicken ovarian tumor subtypes. Representative H&E (A), ovalbumin (B) and IgG (C) images of an endometrioid tumor. Representative H&E (D), ovalbumin (E) and IgG (F) images of a serous tumor. Representative H&E (G), ovalbumin (H) and IgG (I) images of an “oviduct” tumor. Representative H&E (J), ovalbumin (K) and IgG (L) images of normal ovary. Ovalbumin protein expression (green) is obvious in endometrioid (B), serous (E) and “oviduct” (H) tumors and not present in normal ovary (K). Autofluorescence of red blood cells is visible in the normal ovary. Scale bar = 100μm.

Table 3.

Histological subtypes of chicken ovarian tumors among treatments.

| Treatment | Endometrioid (%) | Serous (%) | “Oviduct” (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5 (45) | 1 (9) | 5 (45) |

| P+E | 1(50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) |

| P | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| E | 3 (27) | 4 (36) | 4 (36) |

Egg production

Administration of progestin alone or in combination with estrogen significantly decreased egg production compared to the control treatment (p<0.01; Figure 2). There was no significant effect on egg production for the hens treated with estrogen alone compared to the control treatment.

Figure 2.

Effect of treatment on egg production (n=231). P+E or P significantly decreased egg production compared to control (p<0.01). There was no significant effect on egg production for the hens treated with E compared to control.

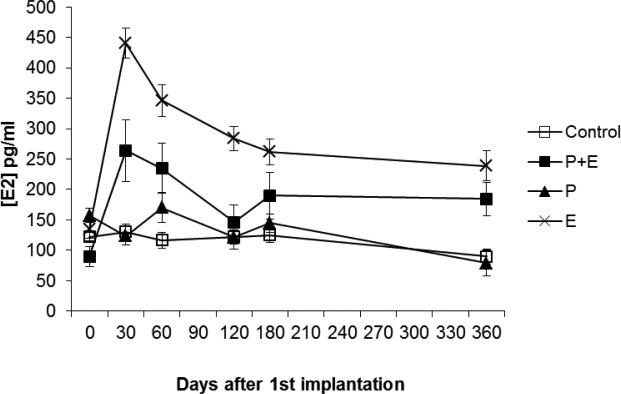

Plasma estradiol levels

Hens treated with estrogen alone (p<0.01) or in combination with progestin (p<0.05) had significantly higher plasma estradiol levels compared to the control group (Figure 3). As expected, treatment with progestin alone had no effect on plasma estradiol levels compared to the control treatment.

Figure 3.

Effect of treatment on plasma estradiol levels (n=8-14 hens per treatment). E (p<0.01) or P+E (p<0.05) significantly elevated plasma estradiol levels compared to control. Treatment with P had no effect on plasma estradiol levels compared to control.

TUNEL assay

We analyzed apoptosis in ovaries of hens lacking neoplasms and found no significant effect of hormone treatment on apoptosis in either the OSE or the stroma (data not shown).

Proliferation assay

PCNA expression was also assessed in ovaries of hens lacking neoplasms and we observed positive expression mainly in the granulosa cell layer of ovarian follicles in all treatment groups. There was no significant effect of treatment on proliferation in either the OSE or the stroma (data not shown).

Discussion

We have shown that administration of progestin, either alone or in combination with estrogen, decreases ovarian cancer prevalence in the hen (Table 1). In fact, treatment with progestin alone, or in combination with estrogen, significantly reduced the risk by 91% and 81%, respectively. These results extend a previous study which reported a 15% reduction in ovarian cancer in hens treated with MPA [9]. One difference between the previous study and the current one is the duration of MPA administration. In the Barnes et al study, hens were injected with MPA three times during the treatment period, resulting in decreased egg production for 4 weeks immediately following each injection and increased egg production thereafter. On average, egg production was decreased by an estimated 24% in the hens treated with MPA. In contrast, we injected hens with MPA every 3-4 weeks suppressing egg production for approximately 16 months (Figure 2), effectively reducing egg production by 57% and 52% in the P and P+E treatment groups, respectively, compared to control treatment. This treatment scheme resulted in a larger reduction in risk compared to the Barnes et al study, suggesting that the onset of ovarian cancer is related to ovulatory events.

In the 1970's Fathalla proposed the “incessant ovulation” hypothesis [20]. This hypothesis is based on the idea that ovulation results in the repeated rupture and repair of the OSE. Over time, this cyclical damage could result in genetic mutations that predispose these cells to become cancerous. Women with high lifetime ovulation numbers would therefore have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. Epidemiological studies in women support this hypothesis. Pregnancy and oral contraceptive use are associated with decreased risk of ovarian cancer and both reduce the number of ovulatory events [21].

In addition to our results, other studies in the hen indicate an association between the number of ovulatory events and the risk of ovarian cancer. Fredrickson observed a difference in ovarian cancer prevalence between two flocks of hens with different ovulation rates [5]. In his study, one flock of hens exhibited a higher rate of egg production as well as a higher incidence of genital tumors (including ovarian tumors) compared to another flock [5]. Giles et al reported a significantly decreased incidence of ovarian cancer in restricted ovulator (RO) hens compared to wild-type (WT) hens [14]. RO hens have a mutation that affects their ability to incorporate yolk into the developing follicle and consequently ovulate significantly fewer times than their WT siblings [22]. Interestingly, RO hens have a hormone profile associated with a high risk of ovarian cancer (low progesterone, high estrogen; [23, 24]) further suggesting that ovulation is linked to ovarian cancer risk. More recently, Carver et al (2011) have shown that caloric restriction in hens decreases ovulatory events, as well as prevalence of ovarian adenocarcinoma [25].

Collectively, these studies in the hen support the “incessant ovulation” hypothesis since decreased ovulation (egg production) results in a decreased incidence of ovarian cancer. Other studies in the hen have tested alternative chemopreventive agents, including aspirin [7] and flaxseed [8]. Administration of these agents resulted in a decrease in ovarian cancer stage, but did not affect cancer incidence. Interestingly, no effect on egg production was observed with these agents. This is in contrast to the significant decrease of egg production and ovarian cancer prevalence with the progestin treatment, but without an effect on tumor stage, in the current study. Taken together, evidence from ovarian cancer in both women and hens highlights the link between the prevalence of ovarian cancer and ovulation.

The hormonal components of oral contraceptives, progestin and estrogen, are thought to affect the development and/or progression of ovarian cancer. Progesterone has been proposed to protect against ovarian tumor development [26]. This protective effect might be independent of the effect of progestin on ovulation, since women on progestin-only formulations of oral contraceptives are also at reduced risk of ovarian cancer even though ovulation is only suppressed in about 40% of users [27]. Progesterone/progestin inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis in normal OSE [28, 29] has been suggested to explain the protective effect observed with oral contraceptive use. In our study, however, we did not find a significant effect of progestin on apoptosis or proliferation in the OSE or the stroma from normal hens (data not shown). Therefore, it appears that, in the hen, induction of apoptosis or inhibition of proliferation does not account for the protective effect of the treatments that we observed.

Interestingly, tumors we have classified as oviduct-like did not develop in hens treated with P+E or P alone (Table 3). These tumors resemble normal chicken oviduct and are characterized by the presence of large numbers of secretory granules (Figure 1). They may represent subtypes of the endometrioid or serous types which we identified, or higher degrees of tumor differentiation. Further characterization of these tumors, including analysis of molecular markers specific to these subtypes [30, 31], is needed to determine the significance of this result.

In contrast to progesterone, estrogens are thought to promote ovarian tumor progression [32]. Studies have shown that women who undergo estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy have an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer [33-35]. In the current study, hens treated with estrogen (either alone or in combination with progestin) exhibited significantly increased plasma estradiol levels compared to control hens (Figure 3), but there was no effect of estrogen treatment on cancer prevalence (Table 1). Estrogens have been shown to promote cellular proliferation and inhibit apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells [36]. Similar to our results with progestin alone, we did not observe an effect of estrogen on apoptosis or proliferation in the OSE or the stroma from normal hens (data not shown).

Although not statistically significant, a larger percentage of hens diagnosed with serous type tumors were treated with either P+E or E (83%) versus those that were in the control and P treatment groups (17%; Table 3). In humans, serous tumors are considered more aggressive than the other subtypes and the association of estrogen treatment with the serous subtype suggests that estrogen may promote tumor progression in the hen. These results are similar to those seen in a recent study where exogenous estrogen was shown to accelerate the onset of ovarian tumor development and decrease survival in a mouse model of the disease [37]. Although we did not directly measure tumor onset in the current study, hens treated with estrogen alone exhibit a decline in egg production before the hens in the control group (Figure 2). Egg production has been shown to decline in hens with ovarian cancer [7] and it is possible that this decline in egg production signifies an earlier onset of the disease in these hens. Furthermore, a previous study from our lab showed that ovarian tumors in the hen exhibit an up-regulation of estrogen-regulated genes compared to normal ovary [15]. These results suggest that estrogen might play a role in the progression of ovarian cancer in the hen.

Our results indicate that ovulatory events might set the level of risk of the disease and other factors (such as hormones) may modulate this risk. The low incidence of ovarian cancer in hens with suppressed ovulation may be due to a decrease of ovulation-associated genotoxic stress. Studies have shown that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory steroids (NSAIDs) inhibit tumor growth in rodents [38] and decrease tumor stage in hens [7], highlighting the potential role of inflammation in the etiology of ovarian cancer. Genotoxic insults may target either the OSE or the fimbrial mucosa, both proposed sites of origin of ovarian cancer [39]. Administration of oral contraceptives to hens significantly decreased ovarian cancer prevalence, supporting the use of oral contraceptives as chemopreventive agents for ovarian cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. James Giles for technical assistance and aid with manuscript preparation, as well as Ms. Katherine Backel, Ms. Elizabeth McCalley, Ms. Jessye Wojtusik, and Ms. Mila Kundu for technical assistance.

The project described was supported in part by grant number F31GM078742 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2008, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD: 2011. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/, based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sueblinvong T, Carney ME. Current understanding of risk factors for ovarian cancer. Curr Treat Opt Oncol. 2009;10:67–81. doi: 10.1007/s11864-009-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls. Lancet. 2008;371:303–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho S. Estrogen, progesterone and epithelial ovarian cancer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:73. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredrickson TN. Ovarian tumors of the hen. Environ Health Perspect. 1987;73:33–51. doi: 10.1289/ehp.877335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Burford C, Barnes MN, Berry W, Partridge EE, Grizzle WE. Immunohistochemical expression of molecular markers in an avian model: a potential model for preclinical evaluation of agents for ovarian cancer chemoprevention. Gynceol Oncol. 2001;81:373–9. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urick ME, Giles JR, Johnson PA. Dietary aspirin decreases the stage of ovarian cancer in the hen. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:166–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ansenberger K, Richards C, Zhuge Y, Barua A, Bahr JM, Luborsky JL, et al. Decreased severity of ovarian cancer and increased survival in hens fed a flaxseed-enriched diet for 1 year. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes MN, Berry WD, Straughn JM, Kirby TO, Leath CA, Huh WK, et al. A pilot study of ovarian cancer chemoprevention using medroxyprogesterone acetate in an avian model of spontaneous ovarian carcinogenesis. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;87:57–63. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klandorf H, Blauwiekel R, Qin X, Russell RW. Characterization of a sustained-release estrogen implant on oviduct development and plasma Ca concentrations in broiler breeder chicks: modulation by feed restriction and thyroid state. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1992;86:469–82. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(92)90072-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin X, Klandorf H. Effect of estrogen on egg production, shell quality, and calcium metabolism in molted hens. Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol. 1995;110:55–9. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(94)00076-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barua A, Abramowicz JS, Bahr JM, Bitterman P, Dirks A, Holub KA, et al. Detection of ovarian tumors in chicken by sonography. A step toward early diagnosis in humans? J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:909–19. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.7.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barua A, Bitterman P, Abramowicz JS, Dirks AL, Bahr JM, Hales DB, et al. Histopathology of ovarian tumors in laying hens: a preclinical model of human ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:531–9. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a41613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giles JR, Elkin RG, Trevino LS, Urick ME, Ramachandran R, Johnson PA. The restricted ovulator chicken: a unique model for investigating the etiology of ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Oncol. 2010;20:738–44. doi: 10.1111/igc.0b013e3181da2c49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treviño LS, Giles JR, Wang W, Urick ME, Johnson PA. Gene expression profiling reveals differentially expressed genes in ovarian cancer of the hen: support for oviductal origin? Hormones and Cancer. 2010;1:177–86. doi: 10.1007/s12672-010-0024-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giles JR, Olson LM, Johnson PA. Characterization of ovarian surface epithelial cells from the hen: a unique model for ovarian cancer. Exp Biol Med. 2006;231:1718–25. doi: 10.1177/153537020623101108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson PA, Giles JR. Use of genetic strains of chickens in studies of ovarian cancer. Poult Sci. 2006;85:246–50. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joyner KL. In: Theriogenology. Avian medicine: principles and application. Ritchie BW, Harrison GJ, Harrison LR, editors. Zoological Education Network; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giles JR, Shavaprasad HL, Johnson PA. Ovarian tumor expression of an oviductal protein in the hen: a model for human serous ovarian adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:950–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fathalla MF. Incessant ovulation-a factor in ovarian neoplasia? Lancet. 1971;2:163. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukanova A, Kaaks R. Endogenous hormones and ovarian cancer: epidemiology and current hypotheses. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:98–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elkin RG, Zhong Y, Porter RE, Walzem RL. Validation of a modified PCR-based method for identifying mutant restricted ovulator chickens: substantiation of genotypic classification by phenotypic traits. Poult Sci. 2003;82:517–25. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leszczynski DE, Hagan RC, Rowe SE, Kummerow FA. Plasma sex hormone and lipid patterns in normal and restricted-ovulator chickens. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1984;55:280–8. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(84)90113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ocon-Grove OM, Maddineni S, Hendricks GL, Elkin RG, Proudman GA, Ramachandran R. Pituitary progesterone receptor expression and plasma gonadotrophin concentrations in the reproductively dysfunctional mutant restricted ovulator chicken. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2007;32:201–15. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carver DK, Barnes HJ, Anderson KE, Pettite JN, Whitaker R, Berchuck A, et al. Reduction of ovarian and oviductal cancer in calorie-restricted laying chickens. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:562–7. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Risch HA. Hormonal etiology of epithelial ovarian cancer, with a hypothesis concerning the role of androgens and progesterone. J Natl Cancer Institute. 1998;90:1774–86. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.23.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming JS, Beaugie CR, Haviv I, Chenevix-Trench G, Tan OL. Incessant ovulation, inflammation and epithelial ovarian carcinogenesis: revisiting old hypotheses. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;247:4–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivarsson K, Sundfeldt K, Brännström M, Janson PO. Production of steroids by human ovarian surface epithelial cells in culture: possible role of progesterone as growth inhibitor. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:116–21. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez GC, Walmer DK, Cline M, Krigman H, Lessey BA, Whitaker RS, et al. Effect of progestin on the ovarian epithelium of macaques: cancer prevention through apoptosis? J Soc Gynecol Invest. 1998;5:271–6. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(98)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCluggage WG. My approach to and thoughts on the typing of ovarian carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:152–63. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.049478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soslow RA. Histologic subtypes of ovarian cancer: an overview. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:161–74. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31815ea812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunat S, Hoffman P, Pujol P. Estrogens and epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearce CL, Chung KC, Pike MC. Increased ovarian cancer risk associated with menopausal estrogen therapy is reduced by adding a progestin. Cancer. 2009;115:531–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morch LS, Lokkegard E, Andreason AH, Kruger-Kjaer S, Lidegaard O. Hormone therapy and ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:298–305. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sueblinvong T, Carney ME. Current understanding of risk factors for ovarian cancer. Curr Treat Opt Oncol. 2009;10:67–81. doi: 10.1007/s11864-009-0108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng H, Kavanagh JJ, Hu W, Liao Q, Fu S. Hormonal therapy in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Oncol. 2007;17:325–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laviolette LA, Garson K, Macdonald EA, Senterman MK, Courville K, Crane CA, et al. 17β-estradiol accelerates tumor onset and decreases survival in a transgenic mouse model of ovarian cancer. Endocrinology. 2010;151:929–38. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daikoku T, Wang D, Tranguch S, Morrow JD, Orsulic S, DuBois RN, et al. Cyclooxygenase-1 is a potential target for prevention and treatment of ovarian epithelial cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3735–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jarboe EA, Folkins AK, Drapkin R, Ince TA, Agoston ES, Crum CP. Tubal and ovarian pathways to pelvic epithelial cancer: a pathological perspective. Histopathology. 2008;53:127–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.