Abstract

Vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor – 1 signaling in lymphocytes has been shown to regulate chemotaxis, proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation. During T cell activation, VPAC1 mRNA is downregulated, but the effect on its protein levels is less clear. A small number of studies have reported measurement of human VPAC1 by flow cytometry, but murine VPAC1 reagents are unavailable. Therefore, we set out to generate a reliable and highly specific α-mouse VPAC1 polyclonal antibody for use with flow cytometry. After successfully generating a rabbit α-VPAC1 polyclonal antibody (α-mVPAC1 pAb), we characterized its cross-reactivity and showed that it does not recognize other family receptors (mouse VPAC2 and PAC1, human VPAC1, VPAC2 and PAC1) by flow cytometry. Partial purification of the rabbit α-VPAC1 sera increased the specific-activity of the α-mVPAC1 pAb by 20-fold, and immunofluorescence microscopy (IF) confirmed a plasma membrane subcellular localization for mouse VPAC1 protein. To test the usefulness of this specific α-mVPAC1 pAb, we showed that primary, resting mouse T cells express detectable levels of VPAC1 protein, with little detectable signal from activated T cells, or CD19 B cells. These data support our previously published data showing a downregulation of VPAC1 mRNA during T cell activation. Collectively, we have established a well-characterized, and highly species specific α-mVPAC1 pAb for VPAC1 surface measurement by IF and flow cytometry.

Keywords: T cells, vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1, vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 2, pituitary Adenylate Cyclase activating polypeptide – 1, polyclonal antibody, flow cytometry

1. Introduction

Vasoactive intestinal peptide/pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide receptor 1 (VPAC1) is the prototypical, group II, G protein coupled receptor nearly ubiquitously expressed in mammals (Ceraudo et al., 2008). This receptor binds the neuropeptide called vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) with ≈1 nM Kd (Gaudin et al., 1996), and its neuronal source is derived from neurons in the central nervous system (Lorén et al., 1979), and peripheral neurons that deliver this ligand to numerous organs (Felten et al., 1985; Ottaway et al., 1987). Also, VIP is expressed by certain immune cells, including activated CD4 Th2 cells (Danek et al., 1983; Delgado and Ganea, 2001). The signal transduction pathways elicited by VIP/VPAC1 are through differential coupling between Gαs, Gαi and Gαq that appear to be cell context dependent (Van Rampelbergh et al., 1997; McCulloch et al., 2002). Major cellular consequences for the VIP/VPAC1 signaling axis are to regulate electrolyte balance (Schwartz et al., 1974), secretion of soluble mediators (Delgado et al., 1999), proliferation (Rameshwar et al., 2002a), chemotaxis (Johnston et al., 1994) and apoptosis (Delgado and Ganea, 2000). Several disease states have been implicated with abnormal VPAC1 levels, including inflammatory disorders such as Rheumatoid arthritis (Woessner, 1991; Yuko et al., 1999) and inflammatory bowel disease (Abad et al., 2003), and solid cancers originating from the lung, prostate, breast, and brain (Reubi, 1996; Reubi et al., 2000a).

The VPAC1 gene was first cloned in 1992 using a rat lung cDNA library, followed by the cloning of the human VPAC1 gene in 1995, which made an immediate impact regarding the tissue expression profile revealing high expression in lung, liver, and intestines (Ishihara et al., 1992; Sreedharan et al., 1995). A decade later, many antibodies had been developed using peptide sequences from the amino- and carboxyl-terminal regions of VPAC1, as well as, the entire full-length human VPAC1 sequence (Goetzl et al., 1994a; Schulz et al., 2004; Freson et al., 2008). These antibodies proved invaluable for detecting VPAC1 protein expression by end-point analyses including, immuno blots, immunoprecipitation, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence (Goetzl et al., 1994b; Jiang et al., 1998; Schulz et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2008). Interestingly, there are exceedingly few examples of flow cytometry analyses using antibodies to the VPAC receptors, and of these studies that we are aware of, only human VPAC protein was measured (Marie et al., 1999; Langlet et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2006; Delgado et al., 2008; Freson et al., 2008). Indeed, we and others have relied primarily on RT-PCR, and in situ hybridization to measure mouse VPAC1 expression at the mRNA level (Barberi et al., 2007; Dorsam, 2010). Therefore, the need for a species, specific, mouse VPAC1 antibody suitable for flow cytometry would be a valuable resource for the neuroimmunology field.

Some success has, however, been reported using fluorescently conjugated VIP ligands that measured the presence of binding sites on cells (Lara-Marquez et al., 2001b), but this strategy does not distinguish between VPAC1 and a 50% homologous VPAC2 receptor (Igarashi et al., 2002). Radioactively iodinated VIP/PACAP ligand binding assays have also become a routine method for discerning between the non-selective VPAC1 and VPAC2 receptors verses the selective pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide receptor 1 (PAC1) (Vertongen et al., 1997; Reubi et al., 2000b). However, this strategy is dependent on proper recognition of the VIP/PACAP analogues, which can alter: receptor internalization, ligand/receptor affinity, and receptor half-life, thus further complicating the distinction between the known VIP/PACAP receptors (Langer and Robberecht, 2007). Moreover, splice variants of the selective and non-selective VIP/PACAP receptors may in turn alter affinity for their cognate ligand(s) and present an additional variable in identifying the receptor subtype (Markovic and Challiss, 2009). The continued absence of a murine specific VPAC1 antibody suitable for flow cytometry measurements will make it difficult, for example, for the routine identification of hematopoietic subpopulations expressing VPAC1 protein (Delgado et al., 1996).

We have previously published that mouse VPAC1 steady-state mRNA is downregulated during ex vivo TCR activation (anti-CD3 treatment), and this downregulation was blocked in a concentration dependent manner by small molecule inhibitors against Fyn, Lck, and JNK kinases (Vomhof-DeKrey and Dorsam, 2008a). Unfortunately, this study did not measure whether a parallel downregulation of VPAC1 protein levels also occured, which will be critical to establish an authentic functional significance to VPAC1 mRNA downregulation during T cell activation (Vomhof-DeKrey et al., 2008). Therefore, we generated a polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse VPAC1 antibody (α-mVPAC1 pAb) by utilizing a genegun strategy to inject the full-length mouse VPAC1 cDNA for expression in rabbit muscle (Genovac, Freiburg, Germany). The α-mVPAC1 pAb showed high specificity towards functionally active, mouse VPAC1 protein by flow cytometry using overexpressed CHO-K1 transfectants, but failed to cross-react with functionally active, human VPAC1 protein, or mouse and human VPAC2, or PAC1 protein. Importantly, we were able to corroborate our mRNA studies of mVPAC1 downregulation by demonstrating that resting primary T cells (CD44low) showed readily detectable mVPAC1 expression compared to no detection in activated T cells (CD44high) by flow cytometry (Mannering et al., 2002). These studies demonstrate a highly specific, mouse VPAC1 antibody that will provide reproducible flow cytometry data, and therefore, is expected to be an important reagent for the neuroimmunology field.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents

CHO-K1, HT-29, SupT1, Molt4b, and MC3T3-E1 cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). F12-Kaighn's modification medium, McCoy's 5a medium, RPMI-1640 medium, α-Minimum essential medium with 0.2 mM ascorbic acid, penicillin/streptomycin, phosphate buffered saline without Ca2+ or Mg2+, characterized fetal bovine serum and trypsin were purchased from Cellgro (Manassas, VA). α-Minimum essential medium without ascorbic acid, Opti-MEM1, Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent, and the goat anti-mouse IgG-R Phycoerythrin secondary antibody were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The rabbit-anti-mouse VPAC1 antibody (rabbits #133 and #134) was purchased from Genovac (Freiburg, Germany). G418 sulfate and β-glycerophosphate were purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ). Anti-mouse or human CD16/CD32 Fc blocker, mouse-anti-CD4 (clone RM4-4), mouse-anti-CD44 (clone IM7), mouse-anti-CD19 (clone 6D5) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Red blood cell lysis buffer and mouse-anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Melon Gel IgG purification kit and the EZ-link NHS-PEO4 biotinylation kit were purchased from ThermoScientific (West Palm Beach, FL). Qiashredders, RNeasy Mini Kit, and RNase-free DNase I were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). The deoxynucleotides, reverse transcriptase were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). The gene specific primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Fast SYBR green PCR master mix was purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). VIP was purchased from American Peptide (Sunnyvale, CA) and Cyclic AMP EIA Kit from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). The DC protein assay and Silver Stain Plus were obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). All other reagents were ordered from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or VWR (West Chester, PA).

2.2. Antibody production

The anti-mouse VPAC1 polyclonal antibody (α-mVPAC1 pAb) was generated by genetic intradermal immunization of two rabbits using Genegun technology (GENOVAC, Freiburg, Germany). Briefly, an immunization vector (GENOVAC, Freiburg, Germany) encoding for the full length mVPAC1 protein was used to evoke an immune response, and final bleeds were 84 days after initial immunization. Collected immune sera (from two rabbits #133 and #134) were tested by flow cytometry using BOSC23 cells (HEK derived cells; data not shown), which were transiently transfected with a test vector encoding for the full length mVPAC1 protein. The secondary antibody was a goat anti-rabbit IgG-PE (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). The level of rabbit-anti-mVPAC1 antibody binding was measured by flow cytometry.

2.3. Tissue Culture

CHO-K1 cells were cultured in 89% F12-Kaighn's modification medium, 10% characterized fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. HT-29 cells were cultured in 89% McCoy's 5a medium, 10% characterized fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. SupT1 cells and Molt4b cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium, 10% characterized FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. MC3T3-E1 clone 4 cells were cultured in α-Minimum essential medium, 10% characterized heat inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and were differentiated by addition with 0.2 mM ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate for 10-15 days. All cell lines were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2.

2.4. Transient transfections of CHO-K1 cells

One day prior to transfection, 3 × 105 CHO-K1 cells were seeded in 10 cm2 tissue culture wells (6 well plate) in triplicate and grown in complete media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were transfected according to the Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, 5 μg of DNA for vector control or with cDNA of interest (mouse VPAC1, kind gift from Sue O'Dorisio, University of Iowa; human 7TM and 5TM VPAC1, kind gift from Donald Branch, University of Toronto), and 10 μL Lipofectamine 2000 reagent were individually diluted in Opti-MEM1 reduced-serum medium and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. The two solutions were combined and incubated for 20 minutes to allow Liposome:DNA complex formation at room temperature. Complexes were added to cells and cultured for an additional 24 hrs.

2.5. Mice

Wild type mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred in ventilated cabinets (VWR) at North Dakota University as previously published (Benton et al., 2009a). All mouse protocols were approved by the NDSU IACUC board and met all federal guidelines. Mice (6-32 wks old) were euthanized by rapid cervical dislocation. Harvested spleens were minced in RPMI with 10% dFBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at RT, and dispersed splenocytes were passed through a 70 μm sieve and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. Erythrocytes were lysed with 1x RBC lysis buffer from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) as described by the manufacturer, and passed through a 70 μm sieve a second time followed by centrifugation as described above.

2.6. Antibody staining

Indicated cell lines (2 × 105 cells) were blocked with 0.5 μg CD16/CD32 Fc blocker (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) on ice for 10 minutes. Rabbit sera (negative control) or Mellon gel purified, α-mVPAC1 pAb (0.52 mg/ml total protein) was added (1/100 dilution) to cells and incubated on ice for 30 minutes. Cells were washed twice with PBS/0.5% BSA/2 mM EDTA (binding buffer) and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes followed by aspiration. The secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit IgG-R Phycoerythrin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), was added for a final concentration of 4 ug/mL final concentration (1/500 dilution) to cells and incubated on ice for 30 minutes in the dark. Cells were washed as above and resuspended in binding buffer and analyzed for fluorescence intensity by flow cytometry on the Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Ann Arbor, MI). Total splenocytes (1.5 × 106) were resuspended in 100 μL PBS/0.5% BSA using 5 mL Falcon tubes and incubated with the following primary fluorochrome antibodies: CD4 (clone RM4-4, Biolegend), CD44 (clone IM7, Biolegend), CD8 (clone 53-6.7, eBioscience), CD19 (6D5, Biolegend), and melon gel purified (0.22 mg/mL) mVPAC1 Ab with or without biotinylation for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. Cells were washed twice with 1 mL PBS/0.5% BSA, centrifuged for 5 min at 500 × g, supernatants aspirated off and incubated with secondary fluorochrome antibodies, PE-goat anti-rabbit IgG or streptavidin for 15 min at 4 °C in the dark. Cells were washed twice with 1 mL PBS/0.5% BSA, centrifuged for 5 min at 500 × g, and resuspended in 300 μl PBS/0.5% BSA. Flow cytometry was performed on a FacsCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickenson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

2.7. SYBR green Quantitative RT- PCR

Cell lines were lysed and total RNA isolated by RNeasy columns as described by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and previously published (Benton et al., 2009). Total RNA concentration was determined by optical density measurements by 260/280 nm ratios. On-column DNase I treatment was incubated at 37 °C for 45 minutes. Total RNA (2 μg) was used to generate first strand cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's protocol (Vomhof-DeKrey and Dorsam, 2008b). Reactions contained 5 μL cDNA, 2x Fast SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ABI, Foster City, CA), and 500 nM of each appropriate primer (Table 1). PCR reaction conditions were an activation step for 20 seconds at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 3 seconds and anneal/extension at 60°C for 30 seconds. A dissociation curve was performed for each reaction, and only primer sets that generated a single dissociation curve at an appropriate annealing temperature were used. Relative changes were calculated by the ΔΔCt method using mouse β-actin or human HPRT as a reference control gene as previously published (Vomhof-DeKrey and Dorsam, 2008a; Vomhof-DeKrey et al., 2008).

Table 1.

PCR primers used in this study.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse | Accession Number | qPCR/RT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hVPAC1 | ACAAGGCAGCGAGTTTGGAT | GTGCAGTGGAGCTTCCTGAAC | NM_004624 | qPCR |

| hVPAC1 | TGCTTGCCGTCTCCTTCTTCTCT | GATCCTGGTGGTCAGACCAGGGAGA | NM_004624 | RT-PCR |

| hVPAC2 | TAGCCCAGGGTATAAATGGC | AGAGACGTTCCCAGATTTCG | NM_003332 | qPCR |

| hHPRT | GGCAGTATAATCCAAAGATGGTCAA | GTCTGGCTTATATCCAACACTTCGT | NM_000194 | qPCR |

| mVpac1 | AGTGAAGACCGGCTACACCA | TCGACCAGCAGCCAGAAGAA | NM_011703 | qPCR |

| mVpac1 | CCTTCTTCTCTGAGCGGAAGTACTT | CCTGCACCTCACCATTGAGGAAGCAG | NM_011703 | RT-PCR |

| mVpac2 | ATGGATAGCAACTCGCCTTTCTTTAG | GGAAGGAACCAACACATAACTCAAACAG | NM_009511 | qPCR |

| mBeta-actin (Actb) | TGTCCACCTTCCAGCAGATGT | AGCTCAGTAACAGTCCGCCTAGA | NM_007393 | qPCR |

2.8. Melon gel purification

Purification of VPAC1 antibody was completed by Melon Gel IgG purification as described by the manufacturer (ThermoScientific, West Palm Beach, FL). Unpurified antibody (50 μL) was diluted 1:10 in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and incubated for 5 minutes with end-over-end tumbling at room temperature and centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 1 minute to collect purified immunoglobin flow through. Total Protein was determined by DC Protein Assay as described by the manufacturer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Total protein (1 μg) was loaded onto a 5% stacking (0.5 M Tris, 0.4% SDS, Bisacrylamide (37.5:1), pH 6.8)/12% separating (1.5 M Tris, 0.4% SDS, Bis-acrylamide (37.5:1); pH 8.7) SDS-PAGE gel and proteins separated using the Laemmli electrophoreses buffer system (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS) (Laemmli, 1970). Gels were stained with Silver Stain Plus as described by the manufacturer and visualized with a CCD camera (Syngene, Frederick, MD).

2.9. Immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy

CHO-K1 cells were seeded (8 × 104 cells/ chamber) in chamber culture slides (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), washed with PBS, fixed with ice-cold 100% methanol by incubating for 10 minutes at -20°C. Fixed cells were washed with PBS, blocked with 0.5 μg CD16/CD32 Fc Blocker (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) in a binding buffer (1X-PBS (pH 7.4) supplemented with 2% goat or bovine serum) for one hour at room temperature. Mellon gel purified rabbit sera (0.6 mg/ml) at a 1/100 final dilution or α-mVPAC1 pAb (0.5 mg/ml) at a 1/100 dilution was added to cells and incubated on ice for 1 hour, and washed as above. A secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG-R conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE) was incubated with cells in the dark for 1 hour at a 1/500 final dilution followed by washing. Some chambers were counter-stained for nuclei detection with 1/1000 dilution Dapi (3 mM), and incubated in the dark for one minute. Cover slides were applied to cells and glycerol and nail polish was used as a protective seal. Visualization of cells by light microscopy and fluorescence microscopy was by a Leica Microsystems inverted microscope (Buffalo Grove, IL) and an epifluoresence light source (Buffalo Grove, IL).

2.10. Biotinylation of α-mVPAC1 pAb

Melon gel purified mVPAC1 antibody and melon gel purified rabbit sera were biotinylated using the EZ-Link NHS-PEO4-Biotinylation kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL) as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, 1.3 mg of protein was incubated with 20x molar excess of biotin for 30 min at RT. Zebra columns were prepared and then the biotinylated protein sample was applied to the column and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 2 min. The eluted biotinylated protein concentration was then measured by Bradford assay and used in antibody staining assays.

3. Results

3.1. Successful detection of VPAC1 protein by flow cytometry

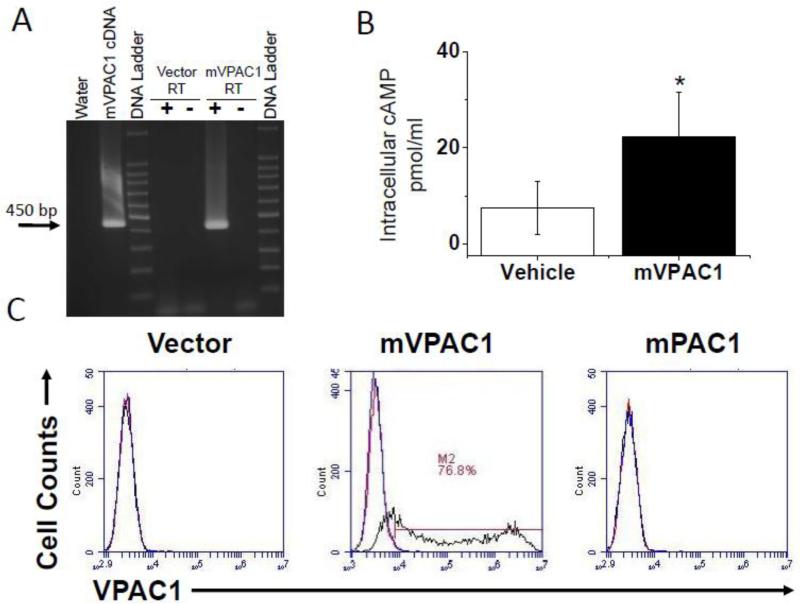

In an attempt to confirm parallel mouse VPAC1 (mVPAC1) downregulation at the protein level during T cell activation, we generated an antibody using Genegun technology (Genovac, Freiburg, Germany). First, we conducted transient transfections of CHO-K1 cells with recombinant mouse VPAC1 protein (Kind gift from Sue O'Dorisio, University of Iowa). These CHO-K1 transfectants (mVPAC1/CHO-K1) were confirmed to express functionally active VPAC1 expression by RT-PCR and [cAMP]i competitive ELISA (Fig. 1A and B). Table 1 summarizes all PCR primers used in this study. After confirming functional mVPAC1 expression on CHO-K1 cells, we used this cellular population to test whether the α-mVPAC1 pAb could detect VPAC1 protein by flow cytometry. The mVPAC1/CHO-K1 transfectants gave a greater percentage of cells shifting when stained with α-mVPAC1 pAb verses vector or rabbit sera controls, respectively (Fig. 1C). These flow cytometry data demonstrate that this new α-mVPAC1 pAb recognizes recombinant mouse VPAC1 protein presented on the plasma membrane when overexpressed in CHO-K1 cells.

Figure 1. Positive detection of functional, mouse VPAC1 receptors.

CHO-K1 populations transiently overexpressing mouse VPAC1 (mVPAC1) protein or vector control (vector) were analyzed after 24 hours in A-C. All experiments are representative from at least 3 independent experiments. A. Transfected cells were used to isolate total RNA isolation, synthesis of cDNA, followed by semi-quantitative PCR analysis from indicated samples. The expected mVPAC1 PCR amplicon (450 bp) is indicated with an arrow, and the DNA ladder used demarcates every 100 bp (1500-100 bp). The positive control is the mVPAC1 cDNA in vector form (pCMV-Tag2B) and +/– RT represents the presence of reverse transcriptase during cDNA synthesis. B. Transfected cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were pretreated with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor (IBMX), treated with VIP (10-6 M) for 15 minutes at 37°C and lysed cells measured for cAMP by competitive ELISA. A cAMP standard curve was performed with all experiments showing linearity in a range of (0.5-500 pmol/ml), and unknown absorbance values were collected within this range. Statistical significance over vector control is a p ≤ 0.05 and represented by an asterisk (*). C. Transfected cells were not stained (red), or stained with 1/50 dilution of α-mVPAC1 pAb followed by 1/1000 goat anti-rabbit–PE secondary (black). Rabbit serum was also used in all panels as a negative, non-specific control (blue). Data are presented in histogram form from flow cytometry analyses for the indicated transfected populations (Accuri C6, Ann Arbor, MI). Gates were set so ≤ 1% was detected for cells alone and rabbit serum negative control.

3.2. Lack of cross-reactivity against human VPAC1 protein by flow cytometry

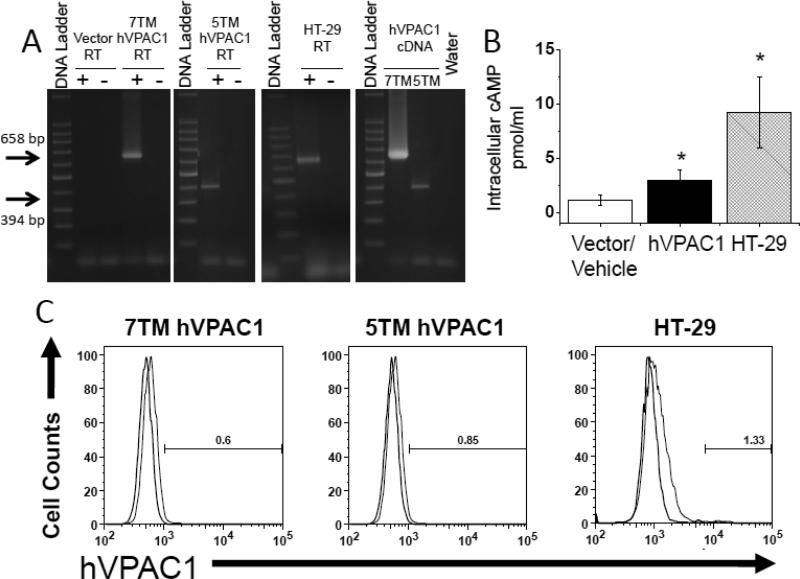

The ability of the α-mVPAC1 pAb to recognize human VPAC1 protein was also tested to determine the degree of crossreactivity to other species. To this end, stable CHO-K1 cells overexpressing human 7TM VPAC1, or the recently identified 5TM VPAC1 isoform (Bokaei, et al. 2006, Kind gift from Dr. Donald Branch, University of Toronto), were established. By RT-PCR, VPAC1 amplicons were readily detected from human VPAC1/CHO-K1 transfectants overexpressing the 7TM and 5TM isoforms, or from human HT-29 cells that express high levels of VPAC1 protein, demonstrating expression of recombinant or endogenous VPAC1 (Fig. 2A). Human 7TM VPAC1/CHOK1 transfectants and HT-29 cells readily increased intracellular cAMP levels in response to exogenously added VIP ligand (Fig. 2B). The 5TM VPAC1 isoform failed to show a detectable cAMP response as expected (data not shown), but were previously shown to be properly presented on the plasma membrane when overexpressed in CHO-K1 cells (Bokaei, et al. 2006). In contrast to mouse VPAC1, α-mVPAC1 pAb gave no detectable shift in fluorescence with CHO-K1 cells overexpressing human recombinant 7TM or 5TM VPAC1, or when using HT-29 cells compared to vector or rabbit serum controls (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that the α-mVPAC1 pAb is species specific as it is unable to recognize functionally active, recombinant or endogenously expressed human VPAC1 protein by flow cytometry, and therefore can distinguish between mouse and human VPAC1 protein.

Figure 2. Lack of detection for functional, human VPAC1 receptor.

CHO-K1 cells transiently overexpressing human 7 transmembrane (TM; full length) VPAC1 (huVPAC1), the 5TM splice variant, and HT-29 cells that express high levels of endogenous VPAC1 (Summers et al., 2003), were analyzed. All experiments are representative from at least 3 independent experiments, and data is presented in an identical manner as in figure 1. CHO-K1 transfectants with 7 and 5 TM huVPAC1 or vector controls, and HT-29 cells were measured for A. VPAC1 mRNA expression by semi-quantitative PCR analysis, B. [cAMP]i measurements after exogenous addition of VIP ligand (1 × 10-6 M) by competitive ELISA. Statistical significance over control is represented by an asterisk (*) with a p value ≤ 0.05, and C. human VPAC1 protein assessment by flow cytometry analysis using α-mVPAC1 pAb (Accuri C6, Ann Arbor, MI). All panels show rabbit serum, non-specific control (light bar) and α-mVPAC1 pAb (dark bar).

3.3. Lack of cross-reactivity against VPAC2 and PAC1 protein by flow cytometry

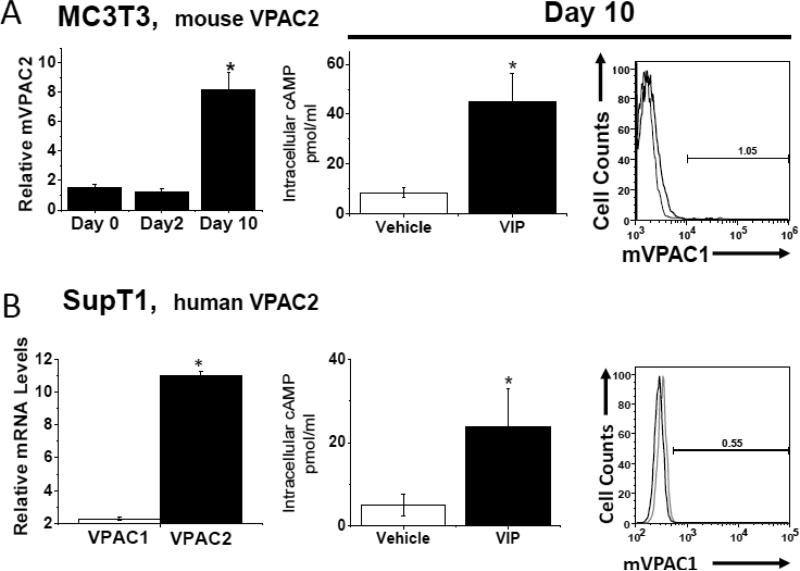

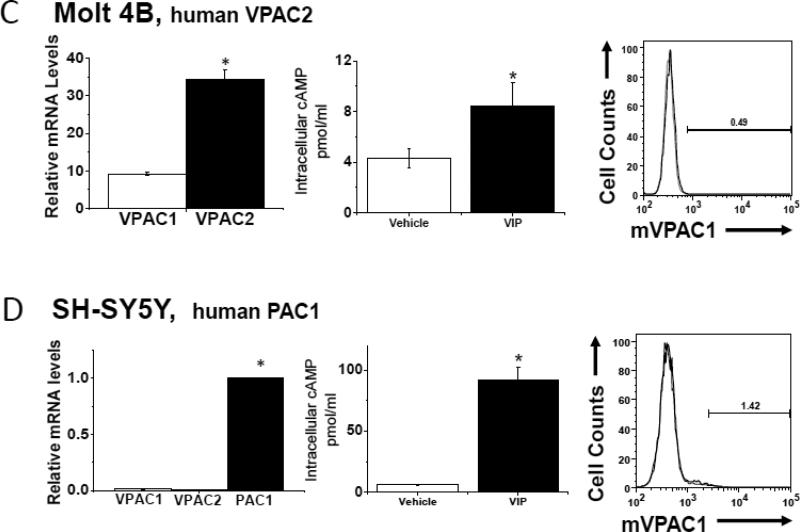

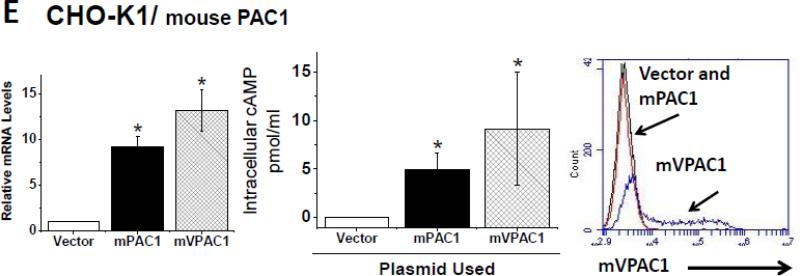

In order to determine whether α-mVPAC1 pAb cross-reacted with mouse or human VPAC2 or PAC1 receptors, cell lines exclusively expressing endogenous VPAC2 or PAC1 (or recombinant transiently transfected CHO-K1 cells) were analyzed. The mouse VPAC2 expressing, differentiated cell line, MC3T3-E1, and the human VPAC2 expressing T cell lines, SupT1 and Molt4, showed no crossreactivity to the α-mVPAC1 pAb despite the presence of functionally active VPAC2 expression (Fig. 3A-C). Likewise, the human SH-SY5Y cell line expressing functionally active PAC1 protein did not demonstrate crossreactivity to the α-mVPAC1 pAb by flow cytometry (Fig. 3D). Since we were unaware of a cell line that exclusively expressed mouse PAC1, we opted to transiently overexpress mPAC1 (Kind gift from Dr. Hitoshi Hashimoto, Osaka University) into CHO-K1 cells, which also showed functional mPAC1 protein on the cell surface, but no detectable cross-reactivity to the α-mVPAC1 pAb (Fig. 3E). Collectively, these results suggest that the α-mVPAC1 pAb is highly specific for mVPAC1, and clearly fails to recognize functionally active, mouse and human VPAC2 and PAC1 protein.,

Figure 3. Lack of detection for functional mouse and human VPAC2 and PAC1 receptors.

Tissue culture cells or transiently transfected CHO-K1 cells expressing mouse or human VPAC2 or PAC1 receptors were analyzed, and representative data from at least 2-6 independent experiments are shown. Statistical significance over control is represented by an asterisk (*) with a p value ≤ 0.05A. Left panel: Mouse monoclonal preosteoblast cells, MC3T3-E1, were differentiated for ten days (Materials and Methods), and assessed for VPAC2 expression by qPCR analysis for indicated time intervals. Data is represented in bar form as means +/- SEM from two independent differentiation experiments. Relative levels of expression were normalized to HPRT. Middle panel: Data in bar graph form is shown from [cAMP]i measurements induced by exogenously added VIP ligand (10-6 M) by competitive ELISA. Right panel: Differentiated MC3T3-E1 cells (day 10) were stained with α-mVPAC1 pAb, and analyzed by flow cytometry. B-E. Three panels of data are presented as in A: left panel, qPCR; middle panel, [cAMP]i and right panel, flow cytometry stained with α-mVPAC1 pAb using B. SupT1, C. Molt-4B cells, D. SH-SY5Y cells and E. Transiently transfected CHO-K1 cells with vector, mouse PAC1 cDNA (mPAC1) or mouse VPAC1 cDNA (mVPAC1) as a positive control.

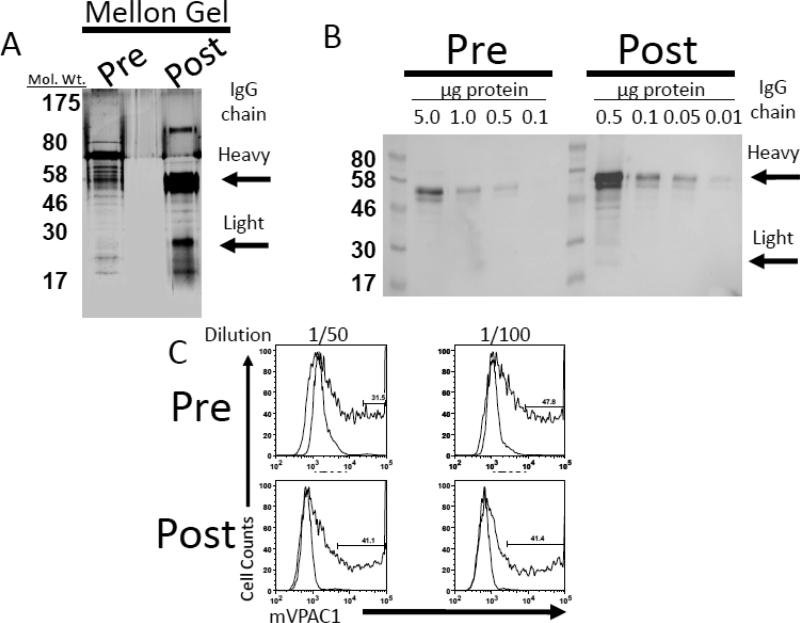

3.4. α-mVPAC1 pAb purification by column chromatography

In an attempt to optimize the detection of mouse VPAC1 protein presented on the plasma membrane of cells by flow cytometry, we used column chromatography to purify the α-mVPAC1 pAb. To this end, a Melon Gel IgG Purification Kit was employed to remove contaminating plasma proteins resulting in an enriched IgG effluent. Post-purification of the α-mVPAC1 pAb resulted in ≈20-fold increase in specific total IgG activity as assessed by SDS-PAGE and Western analysis against a goat α-rabbit HRP (Fig. 4A and B). Moreover, the post-purified α-mVPAC1 pAb gave similar fluorescent shifts by flow cytometry using mVPAC1/CHO-K1 transfectants, but with one order of magnitude less antibody.

Figure 4. Mellon-gel purified rabbit anti-mVPAC1 sera shows similar detection.

Rabbit anti-mVPAC1 sera (50 μl) was diluted with 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5 (450 μl), and applied to a Melon Gel column that has low binding potential for immunoglobulins (IgG). After centrifugation, the flow through was collected and characterized by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis followed by A. silver staining (1 μg total protein) or B. immunoblot using indicated total protein (μg) and probing with a goat α -rabbit secondary conjugated to HRP (1/1000 dilution). Signals were visualized by SuperSignal; West Femto Substrate. C. Antibody staining with rabbit serum (light bar) or pre- and post- Melon Gel purified α-mVPAC1 pAb (dark bar), followed by secondary goat α - rabbit – Alexa 488 Ab. A representative histogram from flow cytometry analysis is shown.

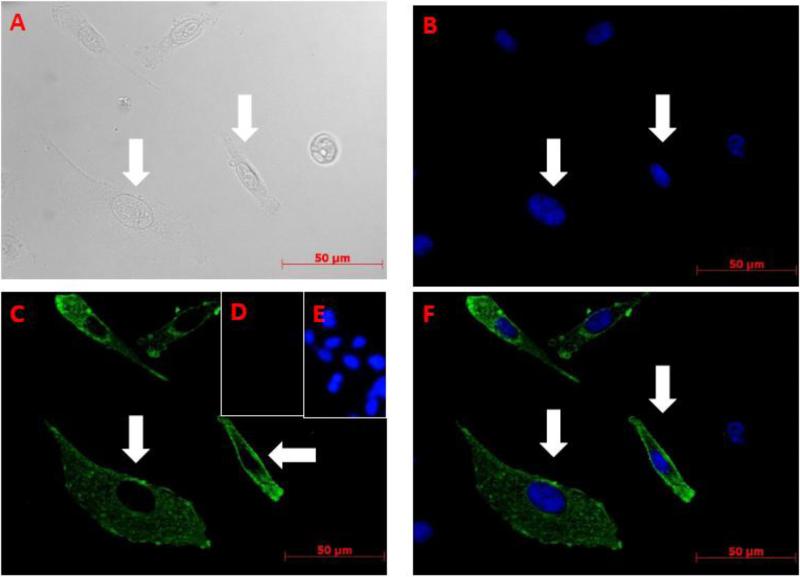

3.5. Morphological validation of plasma membrane subcellular pattern for recombinant mVPAC1 Immunofluorescent microscopy (IF)

VPAC1 protein is the prototypical group B G protein coupled receptor that is targeted to plasma membranes by the secretory pathway (Harikumar et al., 2006). To further validate that the rabbit α-mVPAC1 pAb is detecting authentic mouse VPAC1 protein, we performed IF in an attempt to show a plasma membrane morphological pattern of expression. As expected, our results clearly demonstrate that VPAC1 protein possesses a plasma membrane pattern (see arrows in Figure 5), and a speckled pattern within the cytoplasm and perinuclear regions representing the biosynthetic pathway for the secretory pathway (Lingappa et al., 1978; Blobel et al., 1979). No signal was observed with rabbit serum (data not shown) or with vector transfectants (5D and 5E). In summary, the rabbit α-mVPAC1 pAb is detecting native VPAC1 protein with an expected subcellular pattern.

Figure 5. Immunofluorescent microscopy (IF) demonstrating plasma membrane subcellular localization of recombinant mVPAC1 with the rabbit α-mVPAC1 pAB.

CHO-K1 cells were transfected with vector control or mVPAC1 cDNA by Lipofectamine 2000 and incubated at 37° for 24 hrs. Cells were fixed with 100% methanol, blocked and recombinant mouse VPAC1 expression detected by IF (Materials and Methods). Using the same field of view, CHO-K1 cells transfected with mVPAC1 cDNA were viewed by: A. Light microscopy, B. Dapi staining (cell nuclei). C. Rabbit α-mVPAC1 pAb. D-E. Vector CHO-K1 transfectants stained with D. Rabbit α-mVPAC1 pAb and E. DAPI. F. Merged image of B and C.

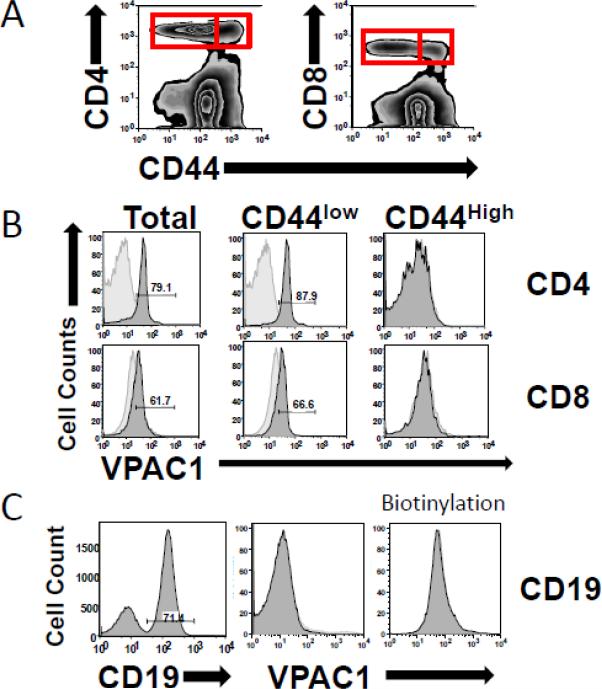

3.6 Mouse VPAC1 protein levels parallel mRNA expression in resting verses activated T cells

High levels of VPAC1 expression in resting CD4 T cells are well-established (Table 2). In addition, the downregulation of VPAC1 mRNA (≥ 80%) has been previously published by our group using various T cell activating ex vivo conditions (anti-CD3, anti-CD3/antiCD28, PMA/ionomycin) (Vomhof-DeKrey and Dorsam, 2008a; Vomhof-DeKrey et al., 2008). To support these studies, and to substantiate the validity of VPAC1 protein downregulation during T cell activation, we measured VPAC1 protein levels presented on primary murine resting (CD44low) and previously activated (CD44high) CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. Figure 6A and 6B shows representative flow cytometry data confirming high expression of VPAC1 in total T cells and resting T cell populations (CD4 or CD8/CD44low-Int.), but no detectable VPAC1 expression in previously activated T cell populations (CD4 or CD8/CD44High; Fig 6A and 6B). B lymphocytes were also tested, and as expected from the relative VPAC1 mRNA expression between B and T cells, no detectable VPAC1 expression was observed (Fig. 6C). Biotinylation of the purified α-mVPAC1 pAb also failed to detect low VPAC1 expression on mouse B cells, and did not improve the sensitivity when using mouse T cells (data not shown). In summary, these data strongly support that VPAC1 mRNA downregulation is paralleled at the protein level during CD4, as well as, CD8 T cell activation. Furthermore, the magnitude of VPAC1 protein downregulation on T cells appears to remove VPAC1 protein from the plasma membrane, thus effectively negating VIP/VPAC1 signaling in activated T cell populations.

Table 2.

| Sample | Rabbit Sera | α-VPAC1 Sera |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse VPAC1 | ||

| mVPAC1/CHO-K1 | 740.5 +/- 12.0 | 22351.5 +/- 2.1 |

| GD4+ CD44 High | 9.20 +/- 5.92 | 8.85 +/- 5.09 |

| GD4+ CD44 Low | 2.46 +/- 1.61 | 28.55 +/- 17.47 |

| GD8+ CD44 High | 22.93 +/- 5.35 | 27.77 +/- 5.05 |

| CD8+ CD44 Low | 9.33 +/- 4.66 | 18.57 +/- 7.02 |

| CD19+ | 17.1 +/- 6.32 | 10.12 +/- 1.12 |

| Human VPAC1 | ||

| 7TM hVPAC1/CHO-K1 | 507.0 +/- 0.0 | 559.5 +/- 19.1 |

| 5TM hVPAC1/CHO-K1 | 580.0 +/- 2.83 | 462.5 +/- 4.95 |

| HT-29 | 1673.5 +/- 266.9 | 1224.5 +/- 134.6 |

| Mouse VPAC2 | ||

| MC3T3-E1 | 2335.5 +/- 870.4 | 3049.5 +/- 1076.9 |

| Human VPAC2 | ||

| Molt4 | 303.5 +/- 4.95 | 377.5 +/- 3.53 |

| SupT1 | 371.5 +/- 29.0 | 406 +/- 62.2 |

| Mouse PAC1/CHO-K1 | 2,725 +/- 690 | 20,606 +/- 144 |

| Human PAC1 | ||

| SH-SY5Y | 1837.3 +/- 1529.5 | 700.0 +/- 409.0 |

Figure 6. Positive detection of mVPAC1 protein expressed in resting but not activated T cells, or CD19 B cells.

Mouse splenocytes were harvested from wild type C57BL6 mice, stained with antibodies as indicated and analyzed on a Becton Dickerson FacsCalibur (Materials and Methods). All antibody staining experiments were conducted 3 independent times with similar results. A. Zebra plots from CD4/8 vs. CD44 antibody staining. Red boxes represent gated primary CD4 or CD8 T cells that express low to intermediate CD44 (resting) or high CD44 expression (activated/memory) used for VPAC1 triple staining. B. Histogram data is presented from indicated cell populations as determined in A for CD4 and CD8 T cells. C. Splenocytes were stained with CD19 to gate B cells (left panel), and co-stained for mVPAC1 (middle panel), or biotinylated α-mVPAC1 pAb (right panel).

4. Discussion

Our study has demonstrated that a newly developed α-mVPAC1 pAb is highly specific for mouse VPAC1 protein as it failed to show crossreactivity with human VPAC1, mouse or human VPAC2, or human PAC1 (Table 2). A one-step column chromatography procedure produced a 20-fold purified pAb that successfully recognized recombinant VPAC1 protein overexpressed in CHO-K1 transfectants, and native VPAC1 protein endogenously expressed on resting, but not previously activated, primary T lymphocytes by flow cytometry. These results corroborate our recent observations of mouse VPAC1 regulation at the mRNA level (Vomhof-DeKrey and Dorsam, 2008a), and also by other laboratories using mouse or human T lymphocytes (Delgado et al., 1996; Lara-Marquez et al., 2001a). Successful flow cytometry measurements of VPAC1 endogenously expressed in primary mouse T cells will allow for future studies delineating the existence of additional, and confirming previously identified, VPAC1 positive hematopoietic subset populations, including bone marrow stem cells, thymocytes and Tregs (Xin et al., 1997; Rameshwar et al., 2002b; Pozo et al., 2009).

To our knowledge, our α-mVPAC1 pAb study is the first successful demonstration using antibodies to measure mouse lymphocyte VPAC1 protein by flow cytometry. Other laboratories have used fluorinated VIP ligand to measure mouse VPAC1 protein by flow cytometry (Lara-Marquez et al., 2001a), but due to the highly unstable nature of these conjugated VIP ligands (personal communication), our α-mVPAC1 pAb offers a more stable and highly specific alternative reagent for the measurement of mouse VPAC1 protein. Flow cytometry detection with antibodies against human VPAC1 protein has been successfully reported by a few laboratories (Goetzl et al., 1994b; Marie et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2006; Freson et al., 2008). These studies have utilized both monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against recombinant and native human VPAC1 protein. One of these studies used anti-human VPAC1 antibodies to neutralize VIP/VPAC1 binding in a mouse in vivo study (Freson et al., 2008). This may presuppose that some anti-human VPAC1 antibodies recognize native mouse protein and may therefore cross-react, but to date have yet to be reported in flow cytometry studies (to our knowledge). In contrast, the antibody generated in our present study is not cross-reactive for human VPAC1, and therefore offers a selective advantage regarding species specific recognition between mouse and human.

A major contribution for the generation of this mouse VPAC1 antibody is that it allowed for the examination of whether VPAC1 mRNA downregulation during T cell activation is accompanied with a concomitant decline in VPAC1 protein levels as assessed by flow cytometry. This observation is important for three major reasons. First, our data supports a common regulatory mechanism for VPAC1 in mouse and humans as a similar downregulation of VPAC1 mRNA and protein was shown using human CD4 T cells (Lara-Marquez et al., 2001a). Second, it substantiates the possibility of a functional significance for the downregulation of VPAC1 mRNA in activated T cells (Vomhof-DeKrey and Dorsam, 2008a). A functional example would be T cell homing to Peyer's Patches, as a lowering of VIP binding sites after mouse CD4 T cell activation is associated with reduced T cell homing (Ottaway, 1984). In addition, it has been shown that VPAC1 signaling can suppress the activation of CD4 T cells by inhibiting IL-2 and IL-4 expression thereby bolstering the T cell activation threshold and inhibiting bystander T cell activation (Sun and Ganea, 1993). Also, regulatory T cells (CD4+/CD25+/FOXP3+) have been shown to be enhanced by VIP/VPAC1 signal transduction. Since CD44high T cells showed limited VPAC1 expression by flow cytometry, the spatial and temporal timing of VIP/VPAC1 signaling could be crucial for Treg differentiation (Pozo et al., 2009). Third, it may suggest that the predominant mode of regulation for VPAC1 expression is controlled at the transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional level rather than the translational level. This notion is substantiated by the agreement between the relative magnitudes of VPAC1 mRNA and protein expression levels between T and B lymphocytes (Vomhof-DeKrey and Dorsam, 2008a; Vomhof-DeKrey et al., 2008; Benton et al., 2009b). However, translational regulation of VPAC1 cannot be ruled out at this time.

Highlights.

A novel, highly species specific rabbit α-mouse VPAC1 pAb was generated

Shows no cross-reactivity by flow cytometry to functional active human VPAC1, or mouse and human VPAC2 and PAC1 protein.

The α-mVPAC1 pAb recognizes VPAC1 protein presented on the plasma membrane as determine by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Table 3.

| Cell Phenotype | Relative mRNA level | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CD4 | 1112 +/- 197 | Benton et al., 2009 & Present study |

| CD8 | 818 +/- 104 | Present study |

| CD19 | 19 +/- 2.1 | Benton et al., 2009 |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Dorsam Lab, and Dr. Sheri Dorsam for thoughtful critiques. We are indebted to Dr. Jodie Haring for her expertise in post flow cytometry data analysis. This study was supported by a NIH/NIDDK career award 1KO1 DK064828 to GPD, and 2P20 RR015566 (Co-PIs are GPD and JMS) and P20 RR016741 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abad C, Martinez C, Juarranz MG, Arranz A, Leceta J, Delgado M, Gomariz RP. Therapeutic effects of vasoactive intestinal peptide in the trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid mice model of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:961–971. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberi M, Muciaccia B, Morelli MB, Stefanini M, Cecconi S, Canipari R. Expression localisation and functional activity of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and their receptors in mouse ovary. Reproduction. 2007;134:281–92. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton KD, Hermann RJ, Vomhof-Dekrey EE, Haring JS, Van der Steen T, Smith J, Dovat S, Dorsam GP. A transcriptionally permissive epigenetic landscape at the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor-1 promoter suggests a euchromatin nuclear position in murine CD4 T cells. Regul Pept. 2009a doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton KD, Hermann RJ, Vomhof-DeKrey EE, Haring JS, Van der Steen T, Smith J, Dovat S, Dorsam GP. A transcriptionally permissive epigenetic landscape at the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor-1 promoter suggests a euchromatin nuclear position in murine CD4 T cells. Regul Pept. 2009b;158:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobel G, Walter P, Chang CN, Goldman BM, Erickson AH, Lingappa VR. Translocation of proteins across membranes: the signal hypothesis and beyond. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1979;33:9–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceraudo E, Murail S, Tan Y-V, Lacapere J-J, Neumann J-M, Couvineau A, Laburthe M. The Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) {alpha}-Helix Up to C Terminus Interacts with the N-Terminal Ectodomain of the Human VIP/Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase-Activating Peptide 1 Receptor: Photoaffinity, Molecular Modeling, and Dynamics. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:147–155. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danek A, O'Dorisio MS, O'Dorisio TM, George JM. Specific binding sites for vasoactive intestinal polypeptide on nonadherent peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1983;131:1173–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M, Ganea D. Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide and Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase-Activating Polypeptide Inhibit Antigen-Induced Apoptosis of Mature T Lymphocytes by Inhibiting Fas Ligand Expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:1200–1210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M, Ganea D. Cutting Edge: Is Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide a Type 2 Cytokine? J Immunol. 2001;166:2907–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M, Martinez C, Johnson MC, Gomariz RP, Ganea D. Differential expression of vasoactive intestinal peptide receptors 1 and 2 (VIP-R1 and VIP-R2) mRNA in murine lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 1996;68:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(96)00063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M, Munoz-Elias EJ, Gomariz RP, Ganea D. Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide and Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase-Activating Polypeptide Enhance IL-10 Production by Murine Macrophages: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. J Immunol. 1999;162:1707–1716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M, Robledo G, Rueda B, Varela N, O'Valle F, Hernandez-Cortes P, Caro M, Orozco G, Gonzalez-Rey E, Martin J. Genetic association of vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor with rheumatoid arthritis: altered expression and signal in immune cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1010–9. doi: 10.1002/art.23482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsam ST, Vomhof-DeKrey Emilie, Hermann Rebecca J., Haring Jodie S., Van der Steen Travis, Wilkerson Erich, Boskovic Goran, Denvir James, Dementieva Yulia, Primerano Donald, Paul Dorsam Glenn. Identification of the early-regulated transcriptome and its associated, interactome in resting and activated murine CD4 T cells. Molecular Immunology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.01.003. doi:10.1016, 2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felten DL, Felten SY, Carlson SL, Olschowka JA, Livnat S. Noradrenergic and peptidergic innervation of lymphoid tissue. J Immunol. 1985;135:755S–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freson K, Peeters K, De Vos R, Wittevrongel C, Thys C, Hoylaerts MF, Vermylen J, Van Geet C. PACAP and its receptor VPAC1 regulate megakaryocyte maturation: therapeutic implications. Blood. 2008;111:1885–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudin P, Couvineau A, Maoret J-J, Rouyer-Fessard C, Laburthe M. Stable expression of the recombinant human VIP1 receptor in clonal Chinese hamster ovary cells: pharmacological, functional and molecular properties. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;302:207–214. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl EJ, Patel DR, Kishiyama JL, Smoll AC, Turck CW, Law NM, Rosenzweig SA, Sreedharan SP. Specific Recognition of the Human Neuroendocrine Receptor for Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide by Anti-Peptide Antibodies. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 1994a;5:145–152. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl EJ, Patel DR, Kishiyama JL, Smoll AC, Turck CW, Law NM, Rosenzweig SA, Sreedharan SP. Specific recognition of the human neuroendocrine receptor for vasoactive intestinal peptide by anti-peptide antibodies. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1994b;5:145–52. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harikumar KG, Morfis MM, Lisenbee CS, Sexton PM, Miller LJ. Constitutive formation of oligomeric complexes between family B G protein-coupled vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and secretin receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:363–73. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi H, Ito T, Hou W, Mantey SA, Pradhan TK, Ulrich CD, Hocart SJ, Coy DH, Jensen RT. Elucidation of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Pharmacophore for VPAC1 Receptors in Human, Rat, and Guinea Pig. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2002;301:37–50. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara T, Shigemoto R, Mori K, Takahashi K, Nagata S. Functional expression and tissue distribution of a novel receptor for vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. Neuron. 1992;8:811–9. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90101-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Wang HY, Yu J, Ganea D. VIP1 and VIP2 receptors but not PVR1 mediate the effect of VIP/PACAP on cytokine production in T lymphocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;865:397–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb11204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JA, Taub DD, Lloyd AR, Conlon K, Oppenheim JJ, Kevlin DJ. Human T lymphocyte chemotaxis and adhesion induced by vasoactive intestinal peptide. J Immunol. 1994;153:1762–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer I, Robberecht P. Molecular mechanisms involved in vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor activation and regulation: current knowledge, similarities to and differences from the A family of G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:724–8. doi: 10.1042/BST0350724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlet C, Langer I, Vertongen P, Gaspard N, Vanderwinden JM, Robberecht P. Contribution of the carboxyl terminus of the VPAC1 receptor to agonist-induced receptor phosphorylation, internalization, and recycling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28034–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Marquez M, O'Dorisio M, O'Dorisio T, Shah M, Karacay B. Selective gene expression and activation-dependent regulation of vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor type 1 and type 2 in human T cells. J Immunol. 2001a;166:2522–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Marquez ML, O'Dorisio MS, O'Dorisio TM, Shah MH, Karacay B. Selective Gene Expression and Activation-Dependent Regulation of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Receptor Type 1 and Type 2 in Human T Cells. J Immunol. 2001b;166:2522–2530. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingappa VR, Katz FN, Lodish HF, Blobel G. A signal sequence for the insertion of a transmembrane glycoprotein. Similarities to the signals of secretory proteins in primary structure and function. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:8667–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorén I, Emson PC, Fahrenkrug J, Björklund A, Alumets J, Håkanson R, Sundler F. Distribution of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in the rat and mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1979;4:1953–1976. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannering SI, Zhong J, Cheers C. T-cell activation, proliferation and apoptosis in primary Listeria monocytogenes infection. Immunology. 2002;106:87–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie J, Wakkach A, Coudray A, Chastre E, Berrih-Aknin S, Gespach C. Functional expression of receptors for calcitonin gene-related peptide, calcitonin, and vasoactive intestinal peptide in the human thymus and thymomas from myasthenia gravis patients. J Immunol. 1999;162:2103–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markovic D, Challiss RA. Alternative splicing of G protein-coupled receptors: physiology and pathophysiology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3337–52. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch DA, MacKenzie CJ, Johnson MS, Robertson DN, Holland PJ, Ronaldson E, Lutz EM, Mitchell R. Additional signals from VPAC/PAC family receptors. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2002;30:441–446. doi: 10.1042/bst0300441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaway CA. In vitro alteration of receptors for vasoactive intestinal peptide changes the in vivo localization of mouse T cells. J Exp Med. 1984;160:1054–69. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.4.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaway CA, Lewis DL, Asa SL. Vasoactive intestinal peptide-containing nerves in Peyer's patches. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 1987;1:148–158. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(87)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo D, Anderson P, Gonzalez-Rey E. Induction of alloantigen-specific human T regulatory cells by vasoactive intestinal Peptide. J Immunol. 2009;183:4346–59. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rameshwar P, Gascon P, Oh HS, Denny TN, Zhu G, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) inhibits the proliferation of bone marrow progenitors through the VPAC1 receptor. Experimental hematology. 2002a;30:1001–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rameshwar P, Gascon P, Oh HS, Denny TN, Zhu G, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) inhibits the proliferation of bone marrow progenitors through the VPAC1 receptor. Exp Hematol. 2002b;30:1001–9. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC. In Vitro Identification of VIP Receptors in Human Tumors: Potential Clinical Implications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1996;805:753–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb17553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Laderach U, Waser B, Gebbers J-O, Robberecht P, Laissue JA. Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide/Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase-activating Peptide Receptor Subtypes in Human Tumors and Their Tissues of Origin1. Cancer Res. 2000a;60:3105–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Laderach U, Waser B, Gebbers JO, Robberecht P, Laissue JA. Vasoactive intestinal peptide/pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide receptor subtypes in human tumors and their tissues of origin. Cancer Res. 2000b;60:3105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S, Rocken C, Mawrin C, Weise W, Hollt V. Immunocytochemical identification of VPAC1, VPAC2, and PAC1 receptors in normal and neoplastic human tissues with subtype-specific antibodies. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8235–42. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CJ, Kimberg DV, Sheerin HE, Field M, Said SI. Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Stimulation of Adenylate Cyclase and Active Electrolyte Secretion in Intestinal Mucosa. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1974;54:536–544. doi: 10.1172/JCI107790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreedharan SP, Huang JX, Cheung MC, Goetzl EJ. Structure, expression, and chromosomal localization of the type I human vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2939–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers MA, O'Dorisio MS, Cox MO, Lara-Marquez M, Goetzl EJ. A lymphocyte-generated fragment of vasoactive intestinal peptide with VPAC1 agonist activity and VPAC2 antagonist effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:638–45. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.050583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide inhibits interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-4 production through different molecular mechanisms in T cells activated via the T cell receptor/CD3 complex. J Neuroimmunol. 1993;48:59–69. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Hong J, Zang YC, Liu X, Zhang JZ. Altered expression of vasoactive intestinal peptide receptors in T lymphocytes and aberrant Th1 immunity in multiple sclerosis. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1691–700. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rampelbergh J, Poloczek P, Françoys I, Christine D, Winand J, Robberecht P, Waelbroeck M. The pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP I) and VIP (PACAP II VIP1) receptors stimulate inositol phosphate synthesis in transfected CHO cells through interaction with different G proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1997;1357:249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertongen P, Schiffmann SN, Gourlet P, Robberecht P. Autoradiographic visualization of the receptor subclasses for vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) in rat brain. Peptides. 1997;18:1547–54. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(97)00229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vomhof-DeKrey EE, Dorsam GP. Stimulatory and suppressive signal transduction regulates vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor-1 (VPAC-1) in primary mouse CD4 T cells. Brain Behav Immun. 2008a;22:1024–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vomhof-DeKrey EE, Dorsam GP. Stimulatory and suppressive signal transduction regulates vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor-1 (VPAC-1) in primary mouse CD4 T cells. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2008b;22:1024–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vomhof-DeKrey EE, Hermann RJ, Palmer MF, Benton KD, Sandy AR, Dorsam ST, Dorsam GP. TCR signaling and environment affect vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor-1 (VPAC-1) expression in primary mouse CD4 T cells. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:1032–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woessner JF., Jr. Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in connective tissue remodeling. FASEB J. 1991;5:2145–2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Z, Jiang X, Wang HY, Denny TN, Dittel BN, Ganea D. Effect of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) on cytokine production and expression of VIP receptors in thymocyte subsets. Regul Pept. 1997;72:41–54. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(97)01028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuko T, Noboru S, Atsushi K, Tomiaki A, Tsuyoshi S. Evidence for neural regulation of inflammatory synovial cell functions by secreting calcitonin gene-related peptide and vasoactive intestinal peptide in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1999;42:2418–2429. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2418::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Aruva MR, Shanthly N, Cardi CA, Rattan S, Patel C, Kim C, McCue PA, Wickstrom E, Thakur ML. PET imaging of VPAC1 expression in experimental and spontaneous prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:112–21. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]