Abstract

We have recently shown that effective cytokine gene therapy of solid tumors in HLA-A2 Tg (HHD) mice lacking murine MHC class I molecule expression results in the generation of HLA-A2-restricted CD8+ T effector cells selectively recognizing tumor blood vessel-associated pericytes and/or vascular endothelial cells (VEC). Using an HHD model in which HLA-A2neg tumor (MC38 colon carcinoma or B16 melanoma) cells are not recognized by the CD8+ T cell repertoire, we now show that vaccines based on tumor-associated blood vessel antigens (TBVA) elicit protective Tc1-dependent immunity capable of mediating tumor regression or extending overall survival. Vaccine efficacy was not observed if (HLA-A2neg) wild-type C57BL/6 mice were instead used as recipient animals. In the HHD model, effective vaccination resulted in profound infiltration of tumor lesions by CD8+ (but not CD4+) T cells, in a coordinate reduction of CD31+ blood vessels in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and in the “spreading” of CD8+ T cell responses to alternate TBVA that were not intrinsic to the vaccine. Protective Tc1-mediated immunity was durable and directly recognized pericytes and/or VEC flow-sorted from tumor tissue, but not from tumor-uninvolved normal kidneys harvested from these same animals. Strikingly, the depletion of CD8+, but not CD4+, T cells at late time points after effective therapy frequently resulted in the recurrence of disease at the site of the regressed primary lesion. This suggests that the vaccine-induced anti-TBVA T cell repertoire can mediate the clinically-preferred outcomes of either effectively eradicating tumors or policing a state of (occult) tumor dormancy.

Keywords: Vaccine, Pericyte, Vascular Endothelial Cells, Tumor, CD8+ T cells

INTRODUCTION

Cancer vaccines based on tumor-associated antigens (TAA) have been extensively evaluated in both translational models and in the clinic. Although by most accounts TAA-based vaccines have been found to be immunogenic in promoting increased frequencies of Ag-specific T cell responses in a large proportion of treated patients, they have only rarely proven curative (1–3). This limitation in efficacy may relate, at least in part, to the heterogeneity of cancer cells found within a given tumor lesion, particularly with regard to sub-population “immunophenotypes” (4–6). Indeed, many times patients that have exhibited objective clinical responses to immunomodulatory therapies ultimately progress with tumors characterized by defects in their antigen-processing/presentation machinery (APM) and altered immunophenotypes (4, 7, 8).

A theoretical means by which to promote anti-tumor immunity, while coordinately circumventing the (immuno)phenotypic “instability” of cancer cells themselves, involves the development of vaccines eliciting T cells capable of selectively targeting tumor-associated stromal cells, such as (myo)fibroblasts, vascular pericytes and VEC (9–20). Interestingly, prophylactic peptide-based and/or recombinant vaccines based on TBVA such as endoglin (CD105), NG2, PDGFRβ, VEGFR1 or VEGFR2 have been previously reported to provide partial protection against challenge with tumor cell lines that fail to express these antigens, presumably based on T cell-mediated anti-angiogenic activity in the TME (9–11, 21–27). However, when applied therapeutically, such vaccines have only slowed the progressive growth of established tumors and modestly extended the overall survival period of treated mice (11, 24, 27).

In our recent paper (28), we reported that IL-12 cytokine gene-therapy of established HLA-A2neg B16 melanomas growing in HLA-A2 Tg mice results in CD8+ T cell-mediated protective immunity directed against host HLA-A2+ stromal cells within the TME. We now show that therapeutic vaccination of HHD mice with TBVA-derived peptides defined in this previous study results in CD8+ T cell-dependent regression of colon carcinoma and melanoma and long-term protection against disease relapse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

HHD mice are Db × β2-microglobulin (β2M) null, transgenic for the modified HLA-A*0201-hβ2-microglobulin single chain (HHD gene; ref. 29) and exhibit CD8+ T cell responses that recapitulate those observed in HLA-A2+ human donors (28–30). C57BL/6 wild-type mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Female 6–8 week old mice were used in all experiments and were handled in accordance with an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved protocol.

Cell Lines

MC38, a methylcholanthrene-induced (HLA-A2neg) murine colon carcinoma cell line and B16 an HLA-A2neg melanoma cell line (syngenic to the H-2b background of HHD mice) have been described previously (31, 32). The T2 cell line is a TAP-deficient T-cell/B-cell hybridoma that constitutively expresses HLA-A2 (33). All cell lines were free of mycoplasma contamination.

Peptides

All peptides were synthesized using 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry by the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute’s Peptide Synthesis Facility (a Shared Resource). Peptides were >96% pure based on high performance liquid chromatography profile and mass spectrometric analysis performed by the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute’s Protein Sequencing Facility (a Shared Resource).

Production of Murine Bone Marrow (BM)-derived DCs and DC.IL12

DC were generated from BM precursors isolated from the tibias/femurs of HHD mice, as previously described (28). The Ad.mIL-12p70 and Ad.Ψ5 (empty) recombinant adenoviral vectors were produced and provided by the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute’s Vector Core Facility (a Shared Resource), as reported previously (34). Five million (day 5 cultured) DCs were infected at MOI = 50 with Ad.mIL-12p70 or the control, empty vector Ad.Ψ5. While control DC produced < 62.5 pg IL-12p70/ml/48h/106 cells, DC.IL12 cells produced 1–10 ng IL-12p70/ml/48h/106 cells (34).

Vaccine Experiments

For prophylactic experiments, HHD mice were immunized s.c. on the right flank with 100 μl PBS or PBS containing 106 syngenic DC.IL12 cells that had been untreated or pre-pulsed for 4h at 37°C with 10 μM synthetic peptide(s). Immunizations occurred on days −14 and −7, with mice subsequently receiving injections of MC38 (2 × 106) tumor cells in the left flank on d0. In all cases, treatment groups contained 5 mice per cohort. For analysis of tumor cellular composition in repeat experiments, MC38 tumors were isolated by surgical resection 10 days after tumor inoculation and prepared for fluorescence imaging, as described below. For therapeutic experiments, MC38 (2 × 106) or B16 melanoma cells (1 × 105) were injected s.c. in the right flank and allowed to establish/progress for 7 days, at which time, the mice were randomized into cohorts of 5 mice each, with each group exhibiting an approximate mean tumor size of 50–75 mm2. Mice were then untreated or treated with control, syngenic DC.IL12 or DC.IL12 (106 cells injected s.c in the left flank on days 7 and 14) pulsed with synthetic TBVA peptides. In some experiments, as indicated, in vivo antibody depletions (on days 6, 13 and 20 post-tumor inoculation to assess early involvement or on days 60 and 67 or 180 and 187 to assess late involvement) of protective CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells were performed and monitored as previously described (28). In all cases, tumor size (area) was monitored every 3–4 days and is reported as mean +/− SD in mm2.

Evaluation of Specific CD8+ T Cell Responses in HHD Mice

MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) CD8+ splenocytes were harvested (from 3 mice/group) 7 days after the second round of DC-based vaccination (i.e. day 21 after tumor inoculation) and analyzed for reactivity against unpulsed T2 cells, TBVA peptide-pulsed T2 cells, or day 19 (flow-sorted) B16-derived PDGFRβ+CD31negH-2Kb(neg) pericytes or PDGFRβnegCD31+H-2Kb(neg) VEC isolated as previously described (28). Where indicated, 10 μg of anti-HLA-A2 mAb BB7.2 or control anti-class II mAb L243 (both from ATCC, Manassas, VA) were added to replicate co-culture wells. After 48h, supernatants were analyzed for mIFN-γ content by specific ELISA (BD-Biosciences; lower detection limit = 31.3 pg/ml). Data are reported as the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

RT-PCR

Reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) was perfor med using primer pairs as previously described (28).

Fluorescence Imaging of Tumor Sections

Tumor tissue samples were prepared and 6 micron sections prepared as previously reported (34). The following Abs were used: (for T cell analyses), rabbit anti-mouse NG2 (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and alexa488-conjugated anti-CD4 or -CD8β antibodies or matching isotype controls (all from BD-Biosciences); (for vascular analyses), rat anti-mouse CD31 (BD-Biosciences) and rabbit anti-mouse NG2 (Millipore) Abs; (for TBVA), rat anti-mouse CD31 (BD-Biosciences) and guinea pig anti-mouse NG2 (kindly provided by Dr. Bill Stallcup, Burnham Institute for Medical Research) Abs, along with anti-TBVA as described previously (28). Imaging was performed using an Olympus Fluoview 500 Confocal microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA).

Cutaneous wound healing assays

Wound healing analyses were performed in HHD mice as described by Maciag et al. (22).

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA were used to test overall differences between groups (StatMate III, ATMS Co., Tokyo, Japan), with p-values < 0.05 considered significant.

RESULTS

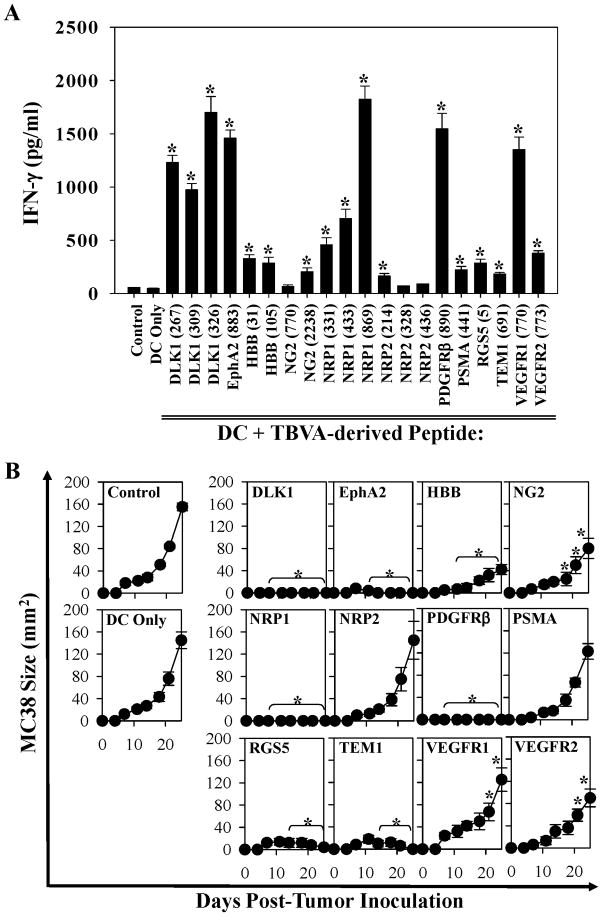

Vaccines incorporating peptide epitopes derived from TBVA are immunogenic and protect HHD mice against HLA-A2neg MC38 tumor challenge

To assess the immunogenicity of TBVA-derived (HLA-A2-presented and evolutionarily-conserved 9-mer or 10-mer; ref. 28) peptides, female HLA-A2 Tg (HHD; lacking murine H-2b class I molecules) mice were vaccinated twice on a weekly schedule with 106 peptide-pulsed, (HHD) DC.IL12 cells. DC.IL12 cells were chosen as a standard “adjuvant” for these studies based on our previous work demonstrating the capacity of this vehicle to effectively promote robust T helper-independent priming of CD8+ T cells when using only class I-presented peptides in the vaccine formulation (34). One week after the booster immunization, CD8+ splenocytes were isolated and analyzed for their ability to secrete IFN-γ in response to peptide-pulsed HLA-A2+ T2 cells in vitro. As shown in Fig. 1A, the majority (17/20; p < 0.05 versus T cells stimulated with DC only) of TBVA-derived peptides analyzed primed Tc1 responses in vivo that could be detected in vitro.

Figure 1. Induction of specific/protective CD8+ T cells reactive against TBVA as a consequence of DC/peptide-based vaccination.

In A, HHD mice (5 animals/cohort) were vaccinated twice (d-14, d-7) s.c. with PBS or with isologous DC.IL12 pulsed with PBS or synthetic peptides (Table S1) derived from the indicated TBVA. In cases where more than 1 peptide was identified for a given target antigen, an equimolar pool of the indicated peptides (each 10 μM) was pulsed onto DC.IL12 and used for vaccination in the relevant cohort. One week after the second immunization, spleens were harvested and splenic CD8+ T cells isolated using MACS-beads (Miltenyi). T cells were stimulated in vitro for 48h using the HLA-A2+ T2 cell line pulsed with relevant TBVA vs. irrelevant HIV-nef190-198 (AFHHVAREL; ref. 24) peptides. Cell-free supernatants were then recovered and IFN-γ levels by ELISA. Data are reported as mean +/− SD for triplicate ELISA determinations, and are representative of 3 independent experiments performed. *p < 0.05 vs. HIV-nef control peptide responses. In B, HHD mice were vaccinated twice (days −14 and −7; right flank) s.c. with PBS or with isologous DC.IL12 pulsed with PBS or synthetic TBVA peptides as indicated in Fig. 1A. In cases where more than 1 peptide is identified for a given target antigen, an equimolar pool of the indicated peptides (each 10 μM) was pulsed onto DC.IL12 and used for vaccination in the relevant cohort. One week after the booster vaccine (i.e. d0), animals were challenged s.c. on their left flank with 2 × 106 MC38 colon carcinoma cells. Tumor growth was then monitored every 3–4 days through d24. All data represent mean tumor area (in mm2) +/− SD determined from 5 mice/cohort, and are representative of 3 independent experiments performed. *p < 0.05 versus DC only on the indicated days.

We noted that the DLK1, EphA2, HBB, NG2, NRP1, NRP2, PDGFRβ, PSMA, RGS5, TEM1, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 antigens were expressed in situ by blood vessel cells in the MC38 colon carcinoma TME (Figs. S1). These findings were similar to our previous observations in the B16 TME (28). This led us to next analyze whether immunization with TBVA-derived peptides on days −14 and −7 would protect HHD mice against a subsequent challenge with HLA-A2neg MC38 tumor cells injected s.c. on d0. As depicted in Fig. 1B, vaccines incorporating peptides from the TBVA DLK1, EphA2, HBB, NRP1, PDGFRβ, RGS5 or TEM1 were effective in preventing HLA-A2neg MC38 tumor establishment or they resulted in the regression of tumors (after a transient period of establishment) in HHD mice. In contrast, vaccines based the TBVA NG2, NRP2, PSMA, VEGFR1 or VEGFR2 yielded minimal protection (Fig. 1B). Based on the data provided in Fig. 1, vaccine immunogenicity and efficacy were not always correlated with one another in the MC38 prophylaxis model (Fig. S2), a finding in accordance with reports for peptide-based vaccines in human clinical trials (1–3).

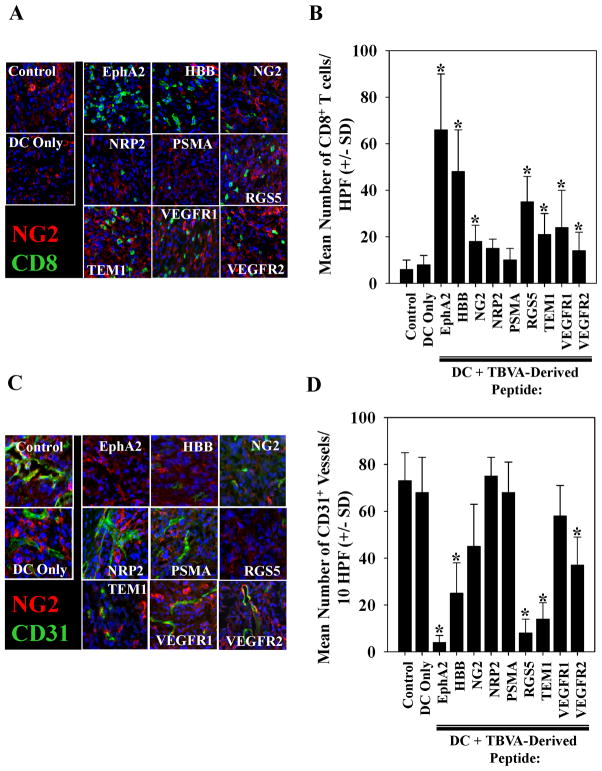

Protective vaccines incorporating TBVA peptides promote enhanced infiltration of the TME by CD8+ T cells in association with an inhibition of tumor vascularity

Since a cohort of the protective vaccines allowed for a transient period of tumor growth (prior to ultimate tumor regression), we isolated MC38 tumor lesions from all cohorts of animals with evidence of disease on day 14 (post-tumor inoculation) and performed immunofluorescence microscopy on tumor sections. We observed that although control (untreated or vaccinated with DC.IL12/no peptide) mice contained few CD8+ T cells in the TME, the majority of the peptide vaccinated cohorts exhibited a variable, but significantly elevated number of CD8+ TILs (Fig. 2A, 2B). In marked contrast, CD4+ T cell infiltration in the TME was sparse and the data were indistinguishable when comparing control vs. vaccinated mice (data not shown). An analysis of vascular structures in these tumors revealed that mice pre-vaccinated with peptides derived from the TBVA EphA2, RGS5 or TEM1 had the greatest degree of suppression in CD31+ vessel counts in the MC38 TME, with somewhat less pronounced effects also noted for groups vaccinated against HBB or VEGFR2 (Fig. 2C, 2D; p < 0.05 vs. untreated mice or mice vaccinated with DC.IL12/no peptide). Correlative analyses indicated an association between the anti-tumor efficacy of vaccines and their ability to promote CD8+ T cell infiltration and reduced vascularity in the TME (Fig. S2).

Figure 2. MC38 tumors in mice pre-vaccinated with TBVA-derived peptides exhibit differential infiltration by CD8+ T cells and alterations in vascular density.

Day 14 MC38 tumors were harvested from HHD mice that had been vaccinated as outlined in Fig. 1B with the indicated peptides (or control PBS or DC.IL12 alone = No peptide). In A., six-micron tissue sections were co-stained with anti-CD8 (green) and anti-NG2 (red) Abs and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. Blue signal = nuclear counterstain using DAPI. Panel B provides a summary of the mean +/− SD number of CD8+ cells per high-power field (HPF) in MC38 tumors isolated from control or vaccinated mice as depicted in panel A. In C., tissue sections were co-stained with anti-CD31 (green) and anti-NG2 (red) Abs and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. Blue signal = nuclear counterstain using DAPI. In D., the mean +/− SD number of CD31+ vessels per HPF of MC38 tumors in control or vaccinated mice are summarized. Representative data is depicted from 1 of 3 independent experiments performed. *p < 0.05 versus DC only or untreated control mice.

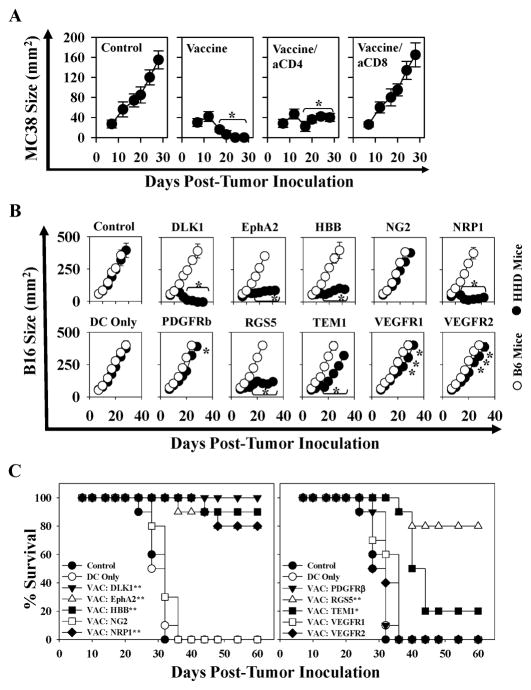

Therapeutic vaccines incorporating TBVA-derived peptide epitopes are effective against established HLA-A2neg MC38 colon carcinomas and HLA-A2neg B16 melanomas in HHD mice

Given the robust anti-tumor activity noted for vaccines based on a subset of TBVA in the prophylactic model, we next studied how well these vaccines would perform as immunotherapies in mice bearing established day 7 s.c. MC38 or B16 tumors. In the MC38 model, we treated HHD mice with DC.IL12 cells pulsed with (an equimolar mixture of) peptides derived from an TBVA shown most capable of regulating tumor growth under prophylactic conditions (Fig. 1B) and exhibiting the highest degree of immunogenicity based on data provided in Fig. 1A (i.e. DLK1326-334, EphA2883-891, HBB31-39, NRP1869-877, PDGFRβ890-898, RGS55-13 and TEM1691-700). As shown in Fig. 3A, the combination peptide vaccine effectively promoted the regression of established MC38 tumors. Furthermore, based on Ab-depletion analyses, therapeutic benefit was largely due to the action of CD8+, but not CD4+, T cells (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. DC.IL12 vaccines containing TBVA-derived peptides are therapeutic against MC38 colon carcinomas and B16 melanomas in HHD mice: requirement for CD8+ T cells and HLA-A2+ host (stromal) cells.

In A, HHD mice bearing established day 7 s.c. MC38 tumors (right flank) were left untreated, or they were vaccinated in the left flank with control DC.IL12 or DC.IL12 pulsed with an equimolar pool (10 μM each) of the following TBVA-derived peptides: DLK1326-334, EphA2883-891, HBB31-39, NRP1869-877, PDGFRβ890-898, RGS55-13 and TEM1691-700. Identical booster vaccines were provided on day 14 post-tumor inoculation. As indicated, 2 vaccine cohorts were treated with depleting anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 mAbs as outlined in Materials and Methods to evaluate the impact of these T cell subsets on therapy outcome. Tumor growth was monitored every 3–4 days through d28. In B, Female HHD or C57BL/6 (B6) mice were inoculated s.c. in the right flank with 1 × 105 B16 (HLA-A2neg) tumor cells. After 7 days, animals were randomized into groups of 5 mice exhibiting tumor lesions with a mean surface area of 60–75 mm2. The mice then received vaccines consisting of isologous control or peptide-pulsed DC.IL12 cells s.c. in the left flank on days 10 and 17 (post-tumor inoculation). In cases where more than 1 peptide was identified for a given target antigen, an equimolar pool of the indicated peptides (each 10 μM) was pulsed onto DC.IL12 and used for vaccination. Tumor size (mean +/− SD) was monitored every 3–4 days through day 34. In A and B, mean tumor area +/− SD is reported for 5 animals/cohort. Data are the representative of those obtained in 2 independent experiments in each case. *p < 0.05 versus DC only on the indicated days. In C, HHD mice bearing s.c. B16 melanomas were treated as described in Fig. 3B and followed through day 60 post-tumor inoculation. Data are reported in Kaplan-Meier plots depicting overall percentage of surviving animals over time. *p < 0.02 versus DC only; ** p < 0.002 versus DC only (with refined p-values for differences between treatment cohorts reported in Table S1). Data are cumulative for 3 independent experiments performed.

Therapeutic vaccines applied to mice bearing B16 melanomas were also effective in suppressing tumor growth if: i.) the vaccine-incorporated peptides derived from the stromal antigens DLK1, EphA2, HBB, NRP1, RGS5 (and to a lesser extent TEM1) and ii.) recipient mice were competent to respond to these peptides in an HLA-A2-restricted manner (Fig. 3B). Hence, none of the vaccines evaluated perturbed B16 tumor growth in syngenic B6 mice, which fail to express the relevant HLA-A2 class I restriction element required for CD8+ T cell recognition of the immunizing peptides. We did not evaluate therapeutic vaccines using the NRP2 or PSMA peptides in the B16 model based on their poor performance in the preliminary MC38 protection model (Fig. 1B).

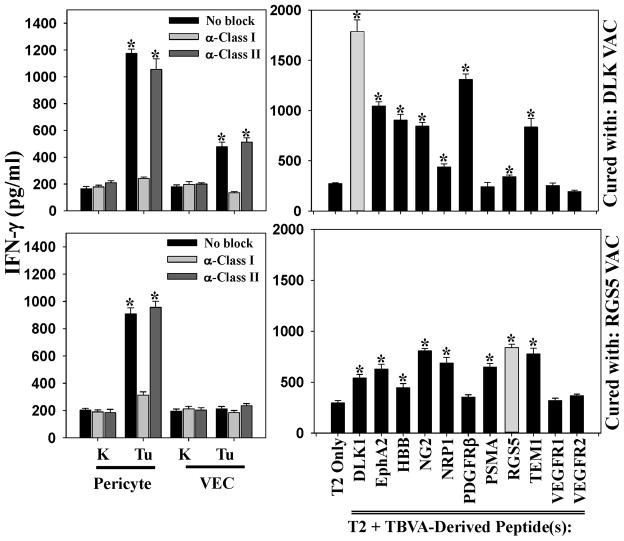

HHD mice cured of B16 tumors by TBVA peptide-based therapeutic vaccines exhibit extended survival and durable Tc1 responses against tumor-associated pericytes and/or VEC, and spreading in anti-TBVA CD8+ T cell repertoire

We followed mice treated in Fig. 3B through 60 days post-tumor inoculation and observed significant survival benefits if the animals had been treated with vaccines containing peptides derived from the TBVA DLK-1, EphA2, HBB, NRP1, RGS5 or TEM1 (Fig. 3C, Table SI). To analyze the status and specificity of Tc1 cells, HHD mice rendered free of B16 melanoma after therapeutic vaccination with DLK or RGS5 peptide-based vaccines were sacrificed 60 days after tumor inoculation. Fresh MACS-isolated spleen CD8+ T cells were then analyzed for reactivity against HLA-A2+PDGFRβ+CD31neg pericytes, HLA-A2+PDGFRβnegCD31+ VEC or HLA-A2neg tumor cells flow-sorted from day 19 B16 tumors growing progressively in untreated HHD mice. As shown in Fig. 4, splenic Tc1 cells isolated from mice cured after vaccination with DLK1 peptides recognized tumor-associated pericytes and VEC in an MHC class I-restricted manner. They failed to recognize pericytes or VEC isolated from the tumor-uninvolved kidneys of these same donor animals. These Type-1 CD8+ T cells strongly recognized the DLK1 peptides used in the protective vaccine formulation, but also (to a variable degree), a number of additional TBVA-derived peptides that were not included in the therapeutic vaccine. Similarly, B16-bearing HHD mice cured using a vaccine based on the RGS55-13 peptide, demonstrated clear Tc1 recognition of tumor (but not tumor-uninvolved kidney) pericytes, as well as, statistically-significant response against HLA-A2+ T2 cells pulsed with peptides derived from the TBVA DLK1, EphA2, NG2, NRP1, PSMA, RGS5 or TEM1 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. HHD mice cured of B16 melanoma by treatment with DC.IL12/peptide vaccination exhibit poly-specific anti-TBVA Tc1 responses.

HHD mice bearing established d7 B16 melanomas were therapeutically vaccinated with peptides derived from the TBVA DLK1 or RGS5 as described in Fig. 3B. Tumors regressed completely over the next 2 weeks. Sixty days after tumor inoculation, CD8+ T cells were MACS-isolated from the spleens of these animals and evaluated for IFN-γ production (by ELISA) in response to pericytes and VEC (flow-sorted from day 19 untreated B16 tumors or tumor-uninvolved kidneys of B16-bearing HHD mice), as well as, HLA-A2+ T2 cells (control or pulsed with the indicated peptides) as described in Materials and Methods. *p < 0.05 versus anti-class I mAb blockade (when evaluating responses against pericytes, VEC or B16 tumor cells) or T2 cells only (when evaluating anti-peptide responses). Data are reflective of responses observed in 3 independent experiments.

HHD mice cured of B16 tumors by TBVA peptide-based therapeutic vaccines either exhibit true “molecular cures” or a state of CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor dormancy

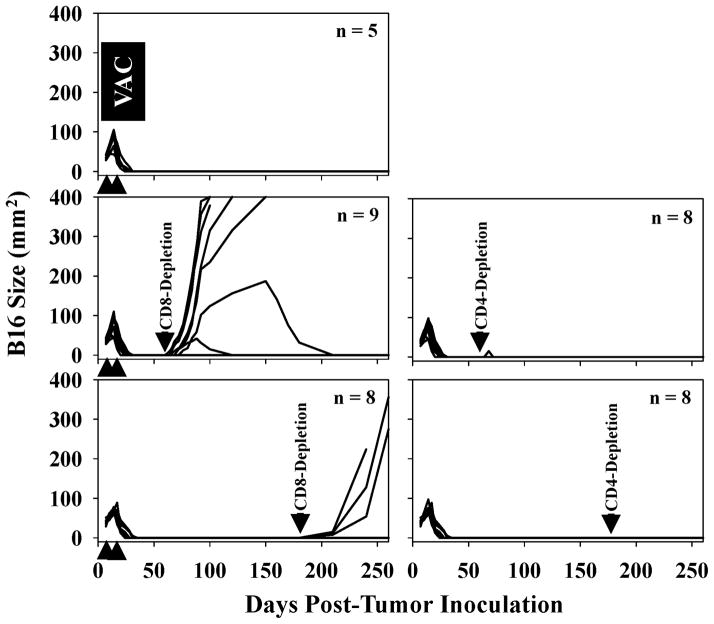

Despite the high-frequency of complete tumor regressors as a consequence of treating B16-bearing HHD mice with TBVA peptide-based vaccines, it was conceivable that TBVA-targeting T cells limit tumor expansion yielding occult disease rather than the complete eradication of cancer cells (i.e. “molecular” cure). To assess this possibility, effectively-treated HHD mice with no evidence of (macroscopic) disease were depleted of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells on days 60 and 67, or 180 and 187 by injection of specific antibodies in vivo. As shown in Fig. 5, depletion of CD8+ T cells, but not CD4+ T cells, resulted in the re-establishment of melanoma growth at sites of the primary tumor placement in 7/9 (i.e. 78% for depletions on days 60/67) and 3/8 (i.e. 38% for depletions on days 180/187) cases, respectively. Interestingly, 2/9 (22%) mice in the day 60/67 CD8+ T cell-depleted group exhibited transient tumor expansion and then “spontaneous” regression over a period of weeks-to-months (Fig. 5), presumably as TBVA/tumor-specific CD8+ T effector cells were recovered in these animals. We also noted that at the time of primary disease recurrence in CD8+ T cell-depleted animals, melanomas did not present in distal cutaneous sites and that metastases were not detected in the lung, liver or brain based on a histopathology examination of resected tissues (data not shown).

Figure 5. In vivo depletion of CD8+, but not CD4+, T cells from a cohort of HHD mice effectively treated with TBVA peptide-based vaccines results in recurrence of disease at the site of primary tumor inoculation.

HHD mice harboring established s.c. B16 melanomas received vaccines consisting of syngenic DC.IL12 pulsed with a mixture of TBVA peptides on days 7 and 14 (post-tumor inoculation) as outlined in Fig. 3A, resulting in tumor regression in 100% of treated animals. On days 60 and 67 or days 180 and 187 (post-tumor inoculation) mice were depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells by i.p. injection with specific antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Control animals received i.p. injections of isotype control Abs. Specific T cell subset depletions were confirmed by flow cytometry analyses performed on peripheral blood obtained by tail venipuncture (data not shown). Animals were then monitored for the reappearance and size of melanomas every 4–7 days. The number of animals evaluated per cohort is indicated within a given panel, with each line representing longitudinal data from a given animal. Data are cumulative from 3 experiments performed.

DISCUSSION

One major finding of the current report is that vaccines based on a subset of TBVA-derived peptides elicit protective/therapeutic immunity against HLA-A2neg (MC38 or B16) transplantable tumors in HHD mice due to the apparent CD8+ T cell targeting of HLA-A2+ pericytes or VEC in the TME. Once protective anti-TBVA immunity was established as a consequence of specific immunization, vaccinated animals exhibited durable protection against challenge with tumors of divergent histology (Fig. S3). Similar peptide-based vaccines applied to CD8-depleted HHD mice or HLA-A2neg recipient (C57BL/6) mice failed to yield treatment benefit, arguing for the critical involvement of CD8+ T cells and the need for these effector cells to target HLA-A2+ stromal cells in vivo (Figs. 4 and S3). A second major finding is that many apparent complete responders in our therapeutic vaccine models retain occult disease, since CD8+, but not CD4+, T cell depletion of “cured” animals resulted in the rapid recurrence of tumors selectively at the site of the original primary lesion in many cases. While in most instances, recurrent tumors grew quickly and proved lethal, in some cases (i.e. 2/10), tumors grew slowly and subsequently underwent spontaneous regression presumably after the Ab-depleted CD8+ T cell repertoire had recovered. These data suggest that TBVA peptide-based vaccines promote complete eradication of tumors or the establishment of a state of (occult) tumor dormancy over extended periods of time which is regulated by vaccine-instigated CD8+ T cells.

The exact nature of residual occult disease in treated animals that recur upon CD8+ T cell depletion remains unknown. In our HHD model system, we failed to detect direct tumor cell recognition by therapeutic T cells, hence HLA-A2neg cancer cells would be afforded the possibility of maintaining microscopic nests that were limited in their expansion potential based on the anti-(tumor) angiogenic activity of protective Tc1 effector cells as suggested in alternate models of immune-mediated tumor dormancy (35). Alternatively, or additionally, slowly replicating/quiescent tumor cells or tumor-initiating cell populations may persist in low numbers in close proximity to blood vessels within the primary lesion site in the occult disease setting, with such cells undergoing a proliferative switch upon removal of local anti-TBVA CD8+ T cells (36, 37). In such circumstances, combinational vaccines simultaneously targeting multiple TBVA, as well as antigens expressed by tumor cells and/or tumor-initiating cells might be expected to yield higher rates of complete cures (14, 38, 39).

Our data suggest that the strongest “clinical” correlates for vaccine efficacy may be the degree of therapeutic Type-1 CD8+ T cell infiltration into the TME and the degree to which Tc1 cells regulate the tumor blood supply. This is in keeping with current paradigms for successful immunotherapy outcome, where levels of specific TIL rather than circulating peripheral blood T cells may be predictive of better clinical prognosis (40). As we have previously suggested (41), treatment-associated vascular “normalization” in the TME may directly result from CD8+ T cell-mediated death or functional disruption of VEC or pericytes (that are required to sustain VEC) in vivo. Such anti-vascular effects may provide a rich source of dead or dying tumor/stromal cells capable of supporting the corollary cross-priming of an evolving protective Tc1 repertoire (41–43). Indeed, we observed that TBVA-based therapeutic vaccines that were capable of inducing tumor clearance resulted in the “spreading” of the protective, memory Tc1 repertoire to include specificity against TBVA unrelated to the original vaccine formulation. Our findings are consistent with the general paradigm of “epitope spreading” in the anti-tumor T cell repertoire as a herald of, or mechanism underlying, superior immunotherapeutic outcome (44–46), and extend this concept to include T cell specificities against TBVA.

Despite theoretical concerns that the anti-TBVA CD8+ T cell response could negatively impact normal tissue blood vessels or the normal process of neoangiogenesis/neovascularization, we failed to detect vaccine-induced: i.) T cell responses against normal tissue pericytes or VEC, or ii.) delay in the kinetics of skin closure after full thickness wounding (data not shown). Such differential recognition of tumor over non-tumor blood vessel cells by Tc1 effector cells may well relate to higher levels of TBVA expression (and by extension their derivative MHC-presented peptides) by tumor- versus normal tissue-associated pericytes and VEC (ref. 28 and Fig. S1B), but this could also reflect tissue site-specific variation in blood vessel cell expression of: i.) MHC Class I APM components, ii.) costimulatory/adhesion or coinhibitory molecules or iii.) “repulsion” molecules that inhibit CD8+ T cell-target cell interactions (4–6, 47–49).

In conclusion, our data support the translational use of TBVA-based vaccines and the integration of TBVA targets in immune monitoring strategies applied to patients with solid forms of cancer. In particular, the ability to immunologically target tumor-associated pericytes and VEC via specific vaccination may pave the way for combinational therapy designs integrating anti-angiogenic agents (i.e. TKI, VEGF/VEGFR antagonists) that have thus far yielded promising, but frequently transient, objective clinical responses in cancer patients (48–50). In these individuals, tumor blood vessels that become refractive to therapy are characterized by a high-degree of coverage with supportive pericytes (50), potentially making these structures ideal targets for TBVA vaccine-induced, anti-pericyte Tc1 cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Christina Goldbach, Mr. Sean Alber and Dr. Simon C. Watkins from the Center for Biologic Imaging (CBI) at the University of Pittsburgh for their assistance with tumor immunofluorescence microscopy imaging. We also thank Drs. Diana Metes, Per Basse and Kyle McKenna for their careful review and constructive comments provided during the preparation of this manuscript.

Nonstandard abbreviations used

- APM

Antigen presentation machinery

- DC

Dendritic cell(s)

- DLK1

Delta-like kinase 1

- HBB

Hemoglobin-β

- HHD

HLA-A2 transgenic mice

- HPF

High-power field

- NRP1/NRP2

Neuropilin-1/2

- PDGFRβ

Platelet-derived growth factor-β

- PSMA

Prostate-specific membrane antigen

- RGS5

Regulator of G-protein signaling 5

- TAA

Tumor-associated antigen

- TBVA

Tumor blood vessel antigen

- TEM1

Tumor endothelial marker-1 (CD248)

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- VEC

Vascular endothelial cells

- VEGFR1/2

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1/-2

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grants P01 CA100327, R01 CA114071 and P50 CA121973 (to W.J.S.). D.B.L. was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship (PF-11-151-01-LIB) from the American Cancer Society. This project used the UPCI Vector Core Facility and was supported in part by the University of Pittsburgh CCSG award P30 CA047904.

REFERENCES CITED

- 1.Jandus C, Speiser D, Romero P. Recent advances and hurdles in melanoma immunotherapy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:711–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vujanovic L, Butterfield LH. Melanoma cancer vaccines and anti-tumor T cell responses. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:301–310. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu Z, Restifo NP. Cancer vaccines: progress reveals new complexities. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:289–294. doi: 10.1172/JCI16216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seliger B, Stoehr R, Handke D, Mueller A, Ferrone S, Wullich B, Tannapfel A, Hofstaedter F, Hartmann A. Association of HLA class I antigen abnormalities with disease progression and early recurrence in prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:529–540. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0769-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkins D, Ferrone S, Schmahl GE, Störkel S, Seliger B. Down-regulation of HLA class I antigen processing molecules: an immune escape mechanism of renal cell carcinoma? J Urol. 2004;171:885–889. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000094807.95420.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seliger B, Maeurer MJ, Ferrone S. Antigen-processing machinery breakdown and tumor growth. Immunol Today. 2000;21:455–464. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiman JM, Kmieciak M, Manjili MH, Knutson KL. Tumor immunoediting and immunosculpting pathways to cancer progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17:275–287. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gajewski TF, Fallarino F, Ashikari A, Sherman M. Immunization of HLA-A2+ melanoma patients with MAGE-3 or MelanA peptide-pulsed autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells plus recombinant human interleukin 12. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:895s–901s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Wang MN, Li H, King KD, Bassi R, Sun H, Santiago A, Hooper AT, Bohlen P, Hicklin DJ. Active immunization against the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor flk1 inhibits tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1575–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niethammer AG, Xiang R, Becker JC, Wodrich H, Pertl U, Karsten G, Eliceiri BP, Reisfeld RA. A DNA vaccine against VEGF receptor 2 prevents effective angiogenesis and inhibits tumor growth. Nat Med. 2002;8:1369–1375. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nair S, Boczkowski D, Moeller B, Dewhirst M, Vieweg J, Gilboa E. Synergy between tumor immunotherapy and anti-angiogenic therapy. Blood. 2003;102:964–971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmeister V, Schrama D, Becker JC. Anti-cancer therapies targeting the tumor stroma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed F, Steele JC, Herbert JM, Steven NM, Bicknell R. Tumor stroma as a target in cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:447–453. doi: 10.2174/156800908785699360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu P, Rowley DA, Fu YX, Schreiber H. The role of stroma in immune recognition and destruction of well-established solid tumors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer CF, Gschwantler-Kaulich D, Fink-Retter A, Haas C, Hudelist G, Czerwenka K, Kubista E. Differential gene expression profile in breast cancer-derived stromal fibroblasts. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110:273–281. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghilardi C, Chiorino G, Dossi R, Nagy Z, Giavazzi R, Bani M. Identification of novel vascular markers through gene expression profiling of tumor-derived endothelium. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson JA, Gillespie JW, Grover A, Tangrea MA, Chuaqui RF, Emmert-Buck MR, Tangrea JA, Libutti SK, Linehan WM, Woodson KG. Gene promoter methylation in prostate tumor-associated stromal cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:255–261. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshiura K, Nishishita T, Nakaoka T, Yamashita N, Yamashita N. Inhibition of B16 melanoma growth and metastasis in C57BL mice by vaccination with a syngeneic endothelial cell line. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okaji Y, Tsuno NH, Kitayama J, Saito S, Takahashi T, Kawai K, Yazawa K, Asakage M, Hori N, Watanabe T, Shibata Y, Takahashi K, Nagawa H. Vaccination with autologous endothelium inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis of colon cancer through autoimmunity. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:85–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matejuk A, Leng Q, Chou ST, Mixson AJ. Vaccines targeting the neovasculature of tumors. Vasc Cell. 2011;3:7. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SH, Mizutani N, Mizutani M, Luo Y, Zhou H, Kaplan C, Kim SW, Xiang R, Reisfeld RA. Endoglin (CD105) is a target for an oral DNA vaccine against breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1565–1574. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0155-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maciag PC, Seavey MM, Pan ZK, Ferrone S, Paterson Y. Cancer immunotherapy targeting the high molecular weight melanoma-associated antigen protein results in a broad antitumor response and reduction of pericytes in the tumor vasculature. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8066–8075. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan CD, Krüger JA, Zhou H, Luo Y, Xiang R, Reisfeld RA. A novel DNA vaccine encoding PDGFRβ suppresses growth and dissemination of murine colon, lung and breast carcinoma. Vaccine. 2006;24:6994–7002. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishizaki H, Tsunoda T, Wada S, Yamauchi M, Shibuya M, Tahara H. Inhibition of tumor growth with anti-angiogenic cancer vaccine using epitope peptides derived from human vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5841–5849. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo Y, Markowitz D, Xiang R, Zhou H, Reisfeld RA. FLK-1-based minigene vaccines induce T cell-mediated suppression of angiogenesis and tumor protective immunity in syngeneic BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2007;25:1409–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong Y, Qian J, Ibrahim R, Berzofsky JA, Khleif SN. Identification of H-2Db-specific CD8+ T-cell epitopes from mouse VEGFR2 that can inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth. J Immunother. 2006;29:32–40. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000175494.13476.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wada S, Tsunoda T, Baba T, Primus FJ, Kuwano H, Shibuya M, Tahara H. Rationale for antiangiogenic cancer therapy with vaccination using epitope peptides derived from human vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4939–4946. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao X, Bose A, Komita H, Taylor JL, Kawabe M, Chi N, Spokas L, Lowe DB, Goldbach C, Alber S, Watkins SC, Butterfield LH, Kalinski P, Kirkwood JM, Storkus WJ. Intratumoral IL-12 gene therapy results in the crosspriming of Tc1 reactive against tumor-associated stromal antigens. Mol Ther. 2011;19:805–814. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Firat H, Garcia-Pons F, Tourdot S, Pascolo S, Scardino A, Garcia Z, Michel ML, Jack RW, Jung G, Kosmatopoulos K, Mateo L, Suhrbier A, Lemonnier FA, Langlade-Demoyen P. H-2 class I knockout, HLA-A2.1-transgenic mice: a versatile animal model for preclinical evaluation of antitumor immunotherapeutic strategies. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3112–3121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3112::AID-IMMU3112>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Firat H, Cochet M, Rohrlich PS, Garcia-Pons F, Darche S, Danos O, Lemonnier FA, Langlade-Demoyen P. Comparative analysis of the CD8+ T cell repertoires of H-2 class I wild-type/HLA-A2.1 and H-2 class I knockout/HLA-A2.1 transgenic mice. Int Immunol. 2002;14:925–934. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi S, Tatsumi T, Takehara T, Sakamori R, Uemura A, Mizushima T, Ohkawa K, Storkus WJ, Hayashi N. Immunotherapy of murine colon cancer using receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2-derived peptide-pulsed dendritic cell vaccines. Cancer. 2007;110:1469–1477. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatano M, Kuwashima N, Tatsumi T, Dusak JE, Nishimura F, Reilly KM, Storkus WJ, Okada H. Vaccination with EphA2-derived T cell-epitopes promotes immunity against both EphA2-expressing and EphA2-negative tumors. J Transl Med. 2004;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stuber G, Leder GH, Storkus WJ, Lotze MT, Modrow S, Székely L, Wolf H, Klein E, Kärre K, Klein G. Identification of wild-type and mutant p53 peptides binding to HLA-A2 assessed by a peptide loading-deficient cell line assay and a novel major histocompatibility complex class I peptide binding assay. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:765–768. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komita H, Zhao X, Taylor JL, Sparvero LJ, Amoscato AA, Alber S, Watkins SC, Pardee AD, Wesa AK, Storkus WJ. CD8+ T-cell responses against hemoglobin-β prevent solid tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8076–8084. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teng MW, Swann JB, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ. Immune-mediated dormancy: an equilibrium with cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:988–993. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ossowski L, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Dormancy of metastatic melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:41–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown CE, Starr R, Martinez C, Aguilar B, D’Apuzzo M, Todorov I, Shih CC, Badie B, Hudecek M, Riddell SR, Jensen MC. Recognition and killing of brain tumor stem-like initiating cells by CD8+ cytolytic T cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8886–8893. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubinett S, Sharma S. Towards effective immunotherapy for lung cancer: simultaneous targeting of tumor-initiating cells and immune pathways in the tumor microenvironment. Immunotherapy. 2009;1:721–725. doi: 10.2217/imt.09.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoda S, Hirohashi Y, Torigoe T, Morita R, Takahashi A, Asanuma H, Nakatsugawa M, Nishizawa S, Tamura Y, Tsuruma T, Terui T, Kondo T, Ishitani K, Hasegawa T, Hirata K, Sato N. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes efficiently recognize human colon cancer stem-like cells. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1805–1813. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haanen JB, Baars A, Gomez R, Weder P, Smits M, de Gruijl TD, von Blomberg BM, Bloemena E, Scheper RJ, van Ham SM, Pinedo HM, van den Eertwegh AJ. Melanoma-specific tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes but not circulating melanoma-specific T cells may predict survival in resected advanced-stage melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:451–458. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0018-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamzah J, Jugold M, Kiessling F, Rigby P, Manzur M, Marti HH, Rabie T, Kaden S, Gröne HJ, Hämmerling GJ, Arnold B, Ganss R. Vascular normalization in RGS5-deficient tumours promotes immune destruction. Nature. 2008;453:410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature06868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manzur M, Hamzah J, Ganss R. Modulation of the “blood-tumor” barrier improves immunotherapy. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2452–2455. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.16.6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Most RG, Currie A, Robinson BW, Lake RA. Cranking the immunologic engine with chemotherapy: using context to drive tumor antigen cross-presentation towards useful antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2006;66:601–604. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tatsumi T, Huang J, Gooding WE, Gambotto A, Robbins PD, Vujanovic NL, Alber SM, Watkins SC, Okada H, Storkus WJ. Intratumoral delivery of dendritic cells engineered to secrete both interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-18 effectively treats local and distant disease in association with broadly reactive Tc1-type immunity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6378–6386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Dissette VB, Amarnani SN, Vu HT, Oseguera D, Wang HJ, Elashoff RM, McBride WH, Mukherji B, Cochran AJ, Glaspy JA, Economou JS. Determinant spreading associated with clinical response in dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:998–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ranieri E, Kierstead LS, Zarour H, Kirkwood JM, Lotze MT, Whiteside T, Storkus WJ. Dendritic cell/peptide cancer vaccines: clinical responsiveness and epitope spreading. Immunol Invest. 2000;29:121–125. doi: 10.3109/08820130009062294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balabanov R, Beaumont T, Dore-Duffy P. Role of central nervous system microvascular pericytes in activation of antigen-primed splenic T-lymphocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:578–587. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990301)55:5<578::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fabry Z, Sandor M, Gajewski TF, Herlein JA, Waldschmidt MM, Lynch RG, Hart MN. Differential activation of Th1 and Th2 CD4+ cells by murine brain microvessel endothelial cells and smooth muscle/pericytes. J Immunol. 1993;151:38–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buckanovich RJ, Facciabene A, Kim S, Benencia F, Sasaroli D, Balint K, Katsaros D, O’Brien-Jenkins A, Gimotty PA, Coukos G. Endothelin B receptor mediates the endothelial barrier to T cell homing to tumors and disables immune therapy. Nat Med. 2008;14:28–36. doi: 10.1038/nm1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Helfrich I, Scheffrahn I, Bartling S, Weis J, von Felbert V, Middleton M, Kato M, Ergün S, Schadendorf D. Resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy is directed by vascular phenotype, vessel stabilization, and maturation in malignant melanoma. J Exp Med. 2010;207:491–503. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.