Abstract

Background

Unexplained variation in outcomes after common surgeries raises concerns about the quality and appropriateness of surgical care. Understanding variation in surgical outcomes may identify processes that could affect the quality of surgical and postoperative care. We sought to examine hospital-level variation in outcomes following inpatient urologic oncology procedures.

Methods

We identified subjects that underwent radical cystectomy, radical nephrectomy, and radical prostatectomy from the Washington State Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System (CHARS) for the years 2003–2007. We measured postoperative length of stay (LOS) and classified LOS exceeding the 75th percentile as prolonged, the occurrence of Agency for Healthcare Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs), readmissions, and death. We adjusted for patient age and comorbidity in random effects multilevel multivariable models that assessed hospital-level outcomes.

Results

We identified 853 cystectomy subjects from 37 hospitals, 3,018 nephrectomy subjects from 51 hospitals, and 8,228 prostatectomy subjects from 51 hospitals. Complications captured by PSIs were rare. Hospital-level variation was most profound for LOS outcomes after nephrectomy and prostatectomy (8.1% and 26.7% of variance in prolonged LOS, respectively), thromboembolic events after nephrectomy (8.0% of variance), and mortality after cystectomy (7.1% of variance).

Conclusions

Hospital-level variation confounds the care of urologic cancer patients in the state of Washington. Transparent reporting of surgical outcomes and local quality improvement initiatives should be considered to ameliorate the observed variation and improve the quality of cystectomy, nephrectomy, and prostatectomy care.

Keywords: prostate carcinoma, kidney carcinoma, bladder carcinoma, quality of care

INTRODUCTION

Unexplained variation in morbidity and mortality after common surgeries raises concerns about the quality and appropriateness of surgical care. Natural explanations for variation include regional differences in disease prevalence, resource discrepancies, and equivocal clinical situations where providers lack evidence-based outcomes on which to base medical decisions.1 In the setting of strong evidence for algorithms of clinical care, variation in resources (such as available equipment or specialized training) may affect treatment selection. Other health care services may be susceptible to patient or provider preferences, especially when limited evidence is available to support health care decision-making. Yet unexplained variation can impact patient health outcomes. Underuse of needed services may allocate patients to less beneficial treatments; misuse of needed services may subject patients to sub-standard outcomes. Understanding surgical variation may identify target areas for quality improvement or health policy initiatives designed to improve appropriate delivery of care.

Within urological care, little is known about practice variation. In general, urologic care likely conforms to patterns seen in other disciplines: effective care is often underused secondary to resource deficiencies, preference-sensitive conditions are subject to wide practice variation, and supply-sensitive interventions are prone to overuse. The Dartmouth Atlas examined surgical care for benign prostate hyperplasia and discovered marked geographic heterogeneity in use of transurethral resection of the prostate.2 Others have documented wide variation in treatment selection for patient preference-sensitive conditions such as prostate cancer,3, 4 as well as underuse of effective treatments such as radical cystectomy for invasive bladder cancer and partial nephrectomy for kidney cancer.5, 6 Identification of unexplained variation in urological outcomes and practice could inform translational health services research to address resource deficiencies and quality concerns. Herein, we examined hospital-level morbidity and mortality following radical cystectomy, radical nephrectomy, and radical prostatectomy in order to identify potential variation in clinical practice.

METHODS

Patient population

We performed a retrospective cohort review of patients undergoing inpatient urologic cancer surgery in Washington State between 2003 and 2007. We accessed data from the Washington Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System (CHARS) to identify all patients who underwent radical cystectomy, radical nephrectomy, and radical prostatectomy discharged from Washington State hospitals. The CHARS database is a statewide hospital discharge dataset and includes abstracted inpatient data linked by encrypted patient identification numbers such that readmissions and subsequent inpatient procedures can be examined, including those occurring at Washington hospitals other than the index hospital. Hospital identification numbers on each abstracted record permit analysis of variation in outcomes by treatment facility.

Using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition procedure and diagnosis codes, we identified subjects undergoing urologic cancer surgery. Diagnosis codes for bladder cancer (ICD-9 codes 188–188.9, 233.7, 236.7, 239.4) were combined with procedure codes (ICD-9 codes 577, 577.1, 577.9) to identify patients receiving radical cystectomies. We used a previously published algorithm to identify patients undergoing radical nephrectomy for presumption of renal cell carcinoma.7 Procedural ICD-9 code 60.5 in conjunction with diagnostic ICD-9 code 185.0 for prostate cancer was used to identify patients undergoing radical prostatectomies. We restricted our sample to cases from hospitals that performed at least two surgeries for each procedure and limited our cohort to adults 18 years of age and older.

Covariates

Covariates associated with variation in urological outcomes available in CHARS included patient age, gender, and primary payer. We maintained age as a continuous variable to permit the same variable definitions for all three surgeries, which have different inherent age ranges. We categorized primary payer into those with Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance (including health maintenance organizations), and those with other insurance (including self-pay and charity care). We used index ICD-9 codes to enumerate the number of comorbidities ascertained using the Elixhauser method.8 Patient race/ethnicity was not available in CHARS during the selected study period.

Individual hospital identifiers permitted evaluation of procedure volume by hospital, as surgical volume has been shown to be associated with morbidity and mortality after urologic cancer surgery.9–12 We stratified hospitals into volume quartiles dependent on their 5-year cumulative cystectomy, nephrectomy, or prostatectomy volume.

Outcome measures

We measured the occurrence of Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs), disposition outcomes, inpatient readmissions after discharge from the index surgery, and death. The PSI software from AHRQ13 was used to tabulate the 30-day risk of events derived from ICD-9 codes. Length of stay (LOS) was determined from the date of surgery and date of discharge for the index admission. We defined prolonged LOS as admission duration greater than the 75th percentile for cystectomy (11 days), nephrectomy (5 days), and prostatectomy (3 days). Alternate disposition was considered discharge to a facility other than home, such as transfer to a skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation center, or death. We examined 30-day and 90-day readmissions for all primary diagnoses under the premise that the majority of all cause readmissions in the postoperative global period would relate to medical and surgical complications of the index urologic cancer surgery. Postoperative all-cause mortality outcomes within 30 and 90 days of surgery were assessed through linkage of CHARS to the Washington State death registry.

Statistical analysis

We present descriptive statistics for the characteristics of our study sample. Outcomes were analyzed as pooled cross-sectional observations. We assessed hospital-level variation in outcomes after cystectomy, nephrectomy, and prostatectomy with random effects multilevel multivariable models based on prior work evaluating surgeon-specific mortality outcomes after cardiovascular surgery in New York and Massachusetts.14, 15 Patient variables represented the level one effects in our models. Hospitals represented the level two random effects in our models. We adjusted for patient differences in age and comorbidity count between hospitals. Post-estimation, we used model solutions for random intercepts to calculate predicted event rates for each hospital. We compared hospitals to the statewide average in outcomes to determine observed-to-expected event ratios with corresponding confidence intervals.16 We considered outlier hospitals those with outcomes that were better or worse than the statewide average at an alpha level of 0.05. The proportional variance attributable to hospital-level factors was determined from the model residual intraclass correlation coefficient.17 All statistics were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

From 61 total acute care hospitals in Washington State, we identified 853 cystectomy subjects from 37 hospitals, 3,018 nephrectomy subjects from 51 hospitals, and 8,228 prostatectomy subjects from 51 hospitals (Table 1). Patients undergoing cystectomies were significantly older than patients undergoing nephrectomies and prostatectomies. Accordingly, Medicare predominated as the primary payer among patients undergoing cystectomies, and private or HMO insurance coverage predominated among patients undergoing prostatectomies. A greater burden of comorbid conditions was identified among patients undergoing cystectomies, who averaged nearly two major comorbidities per patient. A non-significant trend was observed toward a rising incidence of all three oncologic procedures over the study period. High volume cystectomy centers performed an average of at least 4 procedures annually; high volume nephrectomy and prostatectomy hospitals performed an annual average of at least 15 and 34 procedures, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample.

| Radical cystectomy No. (%) (n = 853) |

Radical nephrectomy No. (%) (n = 3,018) |

Radical prostatectomy No. (%) (n = 8,228) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 68.3 ± 10.8 | 61.5 ± 13.3 | 62.1 ± 7.5 | <0.001 |

| 18–49 | 38 (4.5) | 572 (19.0) | 376 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| 50–59 | 142 (16.7) | 789 (26.1) | 2,614 (31.8) | |

| 60–69 | 272 (31.9) | 789 (26.1) | 3,848 (46.8) | |

| ≥ 70 | 401 (47.0) | 868 (28.8) | 1,390 (16.9) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 707 (82.9) | 1,831 (60.7) | 8,228 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| Female | 146 (17.1) | 1,187 (39.3) | ||

| Primary payer | ||||

| Medicare | 494 (57.9) | 1,197 (39.7) | 2,796 (34.0) | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 39 (4.6) | 201 (6.7) | 154 (1.9) | |

| Private/HMO | 305 (35.8) | 1,502 (49.8) | 5,103 (62.0) | |

| Other | 15 (1.8) | 118 (3.9) | 175 (2.1) | |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 0.8 ±0.9 | <0.001 |

| 0 | 129 (15.1) | 817 (27.1) | 3,802 (46.2) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 260 (30.5) | 984 (32.6) | 2,850 (34.6) | |

| 2 | 252 (29.5) | 691 (22.9) | 1,164 (14.2) | |

| ≥ 3 | 212 (24.9) | 526 (17.4) | 412 (5.0) | |

| Year of surgery | ||||

| 2003 | 165 (19.3) | 546 (18.1) | 1,525 (18.5) | 0.63 |

| 2004 | 156 (18.3) | 539 (17.9) | 1,584 (19.3) | |

| 2005 | 161 (18.9) | 615 (20.4) | 1,565 (19.0) | |

| 2006 | 181 (21.2) | 620 (20.5) | 1,651 (20.1) | |

| 2007 | 190 (22.3) | 698 (23.1) | 1,903 (23.1) | |

| Hospitals | 37 | 51 | 51 | |

| 5-year volume, mean ± SD | 23 ± 30 | 59 ± 67 | 161 ± 238 | <0.001 |

| 5-year volume quartiles | ||||

| 1 (lowest volume) | 2–8 | 2–12 | 2–25 | |

| 2 | 9–14 | 13–34 | 26–74 | |

| 3 | 15–20 | 35–76 | 75–173 | |

| 4 (highest volume) | ≥ 20 | ≥ 77 | ≥ 174 |

SD: standard deviation; HMO: health maintenance organization

Within 30 days of urologic cancer surgery, complications flagged by AHRQ PSIs rarely occurred (Table 2). PSIs complicated cystectomy care more commonly than PSIs confounded nephrectomy or prostatectomy care. Disposition outcomes varied by surgical procedure as length of stay greater than the 75th percentile occurred more commonly after cystectomy and nephrectomy than after prostatectomy, and fewer patients were discharged home after cystectomy than after nephrectomy or prostatectomy. Readmission and postoperative mortality occurred more commonly after cystectomy than after nephrectomy or prostatectomy: more than one-third of patients undergoing cystectomies were readmitted within 90 days of surgery.

Table 2.

Frequencies of disposition, readmission, and mortality outcomes after urologic cancer surgery.

| Radical cystectomy No. (%) |

Radical nephrectomy No. (%) |

Radical prostatectomy No. (%) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient safety indicators* | ||||

| Secondary infections | 8 (0.9) | 5 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative DVT/PE | 34 (4.0) | 34 (1.1) | 52 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Wound dehiscence | 17 (2.0) | 8 (0.3) | 5 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Disposition | ||||

| Prolonged length of stay† | 203 (23.8) | 700 (23.2) | 1,024 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| Alternate disposition‡ | 19 (2.2) | 29 (1.0) | 3 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Readmission | ||||

| 30-day | 202 (23.7) | 207 (6.9) | 248 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| 90-day | 308 (36.1) | 388 (12.9) | 383 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Mortality | ||||

| 30-day | 31 (3.6) | 46 (1.5) | 7 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| 90-day | 57 (6.7) | 91 (3.0) | 12 (0.2) | <0.001 |

Within 30 days of surgery

Admission duration longer than the 75th percentile (11 days following radical cystectomy, 5 days following nephrectomy, 3 days following prostatectomy)

Disposition other than home (i.e. skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation center)

DVT: deep venous thrombosis; PE: pulmonary embolus.

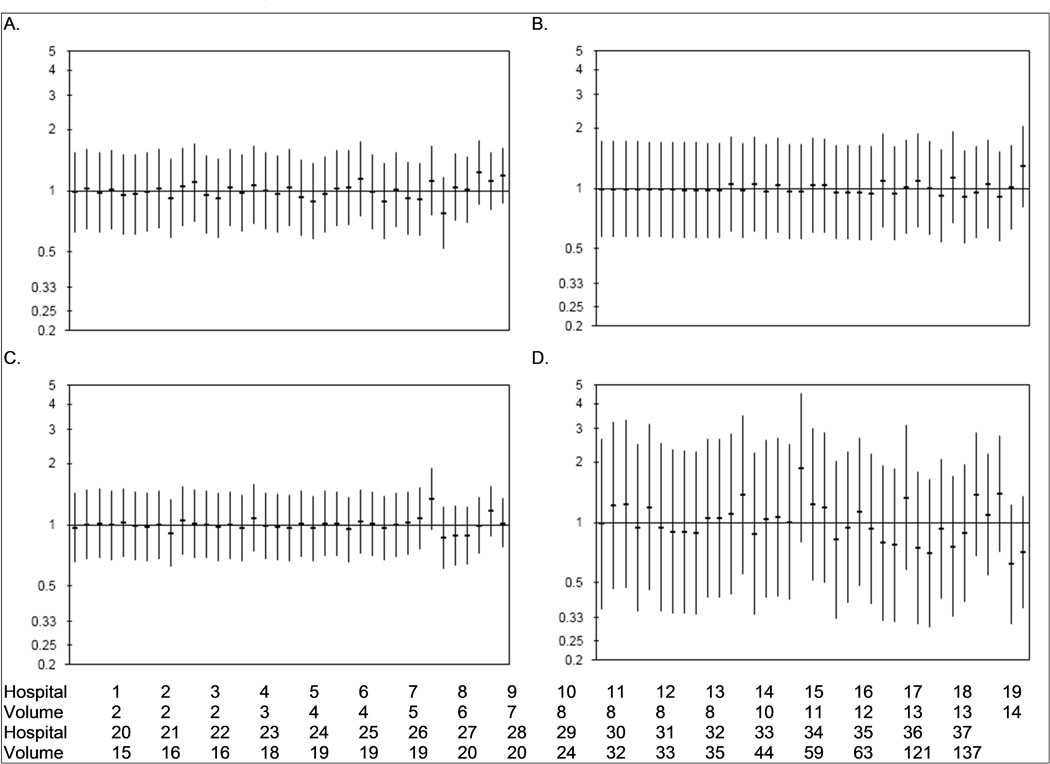

Hospital-level morbidity and mortality outcomes after radical cystectomy are displayed as observed-to-expected ratios of complications in Figure 1. Although event rates varied somewhat by hospital, there were no statistically significant outliers either positively or negatively in the outcomes analyzed after radical cystectomy.

Figure 1.

Hospital variation in prolonged length of stay (> 11 days, 1A), thromboembolic events (1B), 90-day readmission (1C), and 90-day mortality (1D) after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Horizontal bars signify the observed-to-expected ratio of events at each hospital with the vertical bars representing the 95% confidence intervals. Hospitals are ordered by cystectomy volume (from lowest to highest); 5-year cystectomy volume for each hospital is listed at the bottom of the figure.

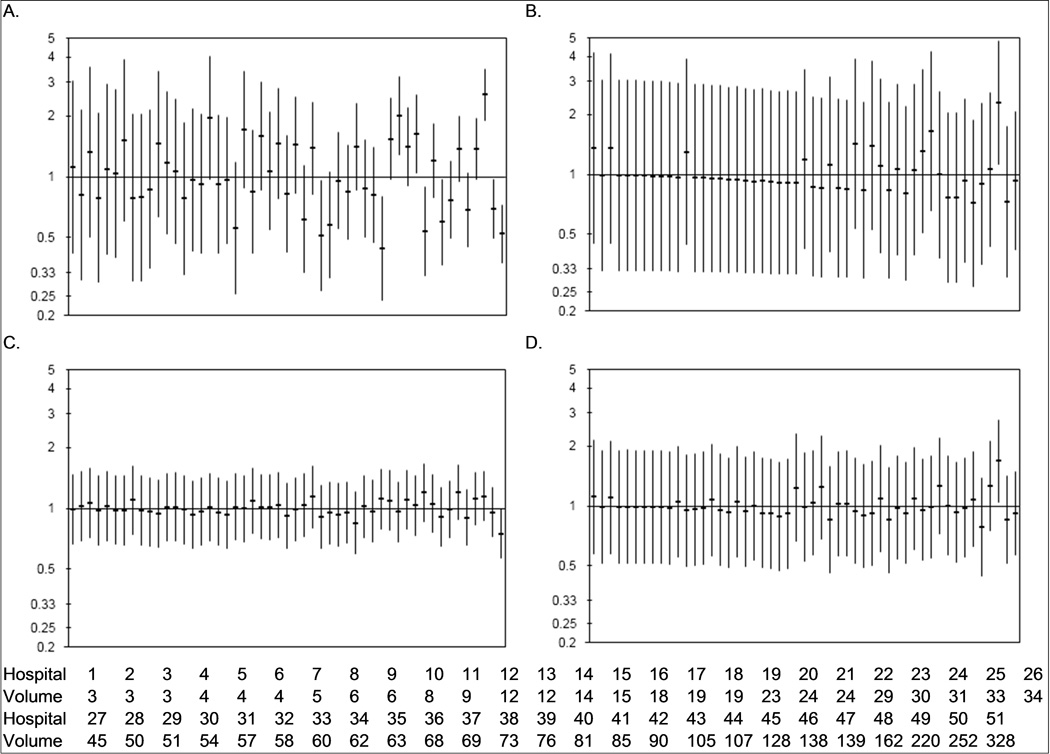

Hospital-level morbidity and mortality outcomes after radical nephrectomy are shown as observed-to-expected event rates in Figure 2. Length of stay outcomes exhibited marked variation by hospital with no obvious relationship between nephrectomy volume and rate of prolonged length of stay. Several hospitals with higher nephrectomy volumes had length of stay outcomes that were worse than the state average. Readmission rates did not vary by hospital. The rate of thromboembolic events and 90-day mortality were largely consistent across hospitals with the exception that one high-volume hospital (Hospital 49) exceeded the state average for both outcomes.

Figure 2.

Hospital variation in prolonged length of stay (> 5 days, 1A), thromboembolic events (1B), 90-day readmission (1C), and 90-day mortality (1D) after radical nephrectomy for kidney tumors. Horizontal bars signify the observed-to-expected ratio of events at each hospital with the vertical bars representing the 95% confidence intervals. Hospitals are ordered by nephrectomy volume (from lowest to highest); 5-year nephrectomy volume for each hospital is listed at the bottom of the figure.

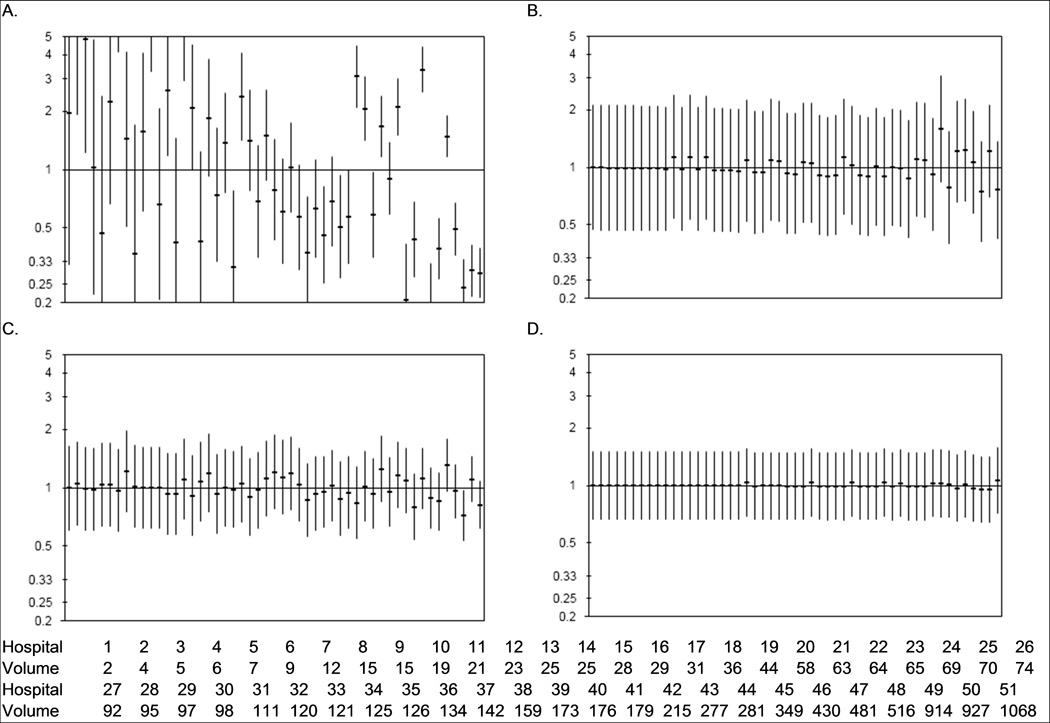

Morbidity and mortality outcomes after radical prostatectomy at the hospital level are displayed in Figure 3. Thromboembolic events, readmission rates, and mortality after prostatectomy varied little by hospital. One high volume hospital had readmission rates that were significantly lower after prostatectomy than the state average. Conversely, length of stay outcomes varied markedly after radical prostatectomy. Several hospitals had length of stay outcomes that were significantly shorter than the state average and a similar number of hospitals were longer length of stay outliers. We observed a trend toward increased odds of prolonged length of stay among lower volume hospitals. In grouping hospitals into volume quartiles, we found that hospitals in the highest volume quartile had significantly shorter mean lengths of stay after radical prostatectomy than hospitals in the lower volume quartiles (−0.45 days vs quartile 3 [95% CI −0.37, −0.53 days], −0.41 days vs quartile 2 [95% CI −0.29, −0.53 days], −0.87 days vs quartile 1 [95% CI −0.67, −1.1 days]).

Figure 3.

Hospital variation in prolonged length of stay (> 3 days, 1A), thromboembolic events (1B), 90-day readmission (1C), and 90-day mortality (1D) after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Horizontal bars signify the observed-to-expected ratio of events at each hospital with the vertical bars representing the 95% confidence intervals. Hospitals are ordered by prostatectomy volume (from lowest to highest); 5-year prostatectomy volume for each hospital is listed at the bottom of the figure.

Table 3 displays the odds ratios derived from the multilevel models for our adjustment variables age and comorbidity, along with the variation in the outcome explained by hospital-level factors for each event. Older age was associated with higher odds of prolonged length of stay and 90-day mortality after cystectomy and nephrectomy, and higher readmission rates after nephrectomy and prostatectomy. Higher comorbidity count was associated with greater complication risk for all events analyzed. Adjusted for patient characteristics, the hospital where patients underwent their surgery factored significantly in length of stay outcomes after nephrectomy and prostatectomy, thromboembolic events after nephrectomy, and mortality after radical cystectomy as measured by the partitioned variance attributed to hospital-level factors.

Table 3.

Multilevel multivariable model results for disposition, readmission, and mortality outcomes after urologic cancer surgery.

| Radical cystectomy OR (95% CI) |

Radical nephrectomy OR (95% CI) |

Radical prostatectomy OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Prolonged length of stay† | |||

| Age in years | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) |

| Comorbidity count | 1.10 (0.97, 1.26) | 1.44 (1.34, 1.56) | 1.47 (1.36, 1.58) |

| Hospital variance | 1.6% | 8.1% | 26.7% |

| Postoperative DVT/PE | |||

| Age in years | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) |

| Comorbidity count | 0.96 (0.72, 1.28) | 1.12 (0.84, 1.48) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.76) |

| Hospital variance | 2.4% | 9.0% | 4.4% |

| 90-day readmission | |||

| Age in years | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) |

| Comorbidity count | 1.23 (1.09, 1.38) | 1.26 (1.16, 1.38) | 1.25 (1.12, 1.39) |

| Hospital variance | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.9% |

| 90-day mortality | |||

| Age in years | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 1.04 (1.03, 1.06) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.15) |

| Comorbidity count | 1.01 (0.80, 1.27) | 1.25 (1.05, 1.48) | 1.36 (0.79, 2.34) |

| Hospital variance | 7.1% | 3.4% | 1.3% |

Admission duration longer than the 75th percentile (11 days following radical cystectomy, 5 days following nephrectomy, 3 days following prostatectomy)

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; DVT: deep venous thrombosis; PE: pulmonary embolus.

DISCUSSION

Hospital-level variation confounds the care of patients undergoing urologic cancer surgery in the state of Washington. In the setting of an increasing surgical burden of bladder cancer, kidney cancer, and prostate cancer, the hospital where patients received their surgical care was an important determinant of their short-term outcomes. The proportion of the variation in the assessed events that was explained by hospital-level factors was substantial for several cystectomy, nephrectomy, and prostatectomy outcomes. Our study has shown that where patients receive their surgical care is as important as the characteristics of the patient and the cancer for which they are undergoing surgery.

Beyond confirming hospital-level variation in outcomes after urologic cancer surgery, our study has several important findings. First, length of stay after nephrectomy and prostatectomy exhibits considerable variation. Following nephrectomy, lower volume hospitals had variable rates of prolonged lengths of stay, but wide confidence intervals around those rates such that no statistically significant outliers were identified. However, among higher volume nephrectomy hospitals, we identified positive and negative outliers for prolonged length of stay. One explanation for this variability could be the differential adoption of minimally invasive surgery for kidney cancer, which is associated with shorter lengths of stay. In Washington State, reflective of national trends, adoption of laparoscopic kidney cancer surgery has lagged relative to adoption of other laparoscopic operations.5, 6 Many high volume nephrectomy centers retain low rates of laparoscopic surgery that may explain their longer lengths of stay. This variability may also be explained by our inability to adjust for cancer-specific information among high volume nephrectomy centers that are more likely to manage complex kidney cancer cases, such as those associated with renal vein and inferior vena cava thromboses, or cases of metastatic kidney cancer undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy. Adjustment for cancer stage would likely alter some of the adjusted event rates, especially among high volume providers managing a large burden of locally advanced kidney cancer. We were surprised to identify such marked variation in prolonged length of stay after prostatectomy. The highest prostatectomy volume quartile of hospitals had lower lengths of stay; however, poor-performing individual high volume prostatectomy hospital outliers were identified. Beyond length of stay, other events studied did not appear to discriminate quality among prostatectomy hospitals. This underscores the need to identify other metrics with which to assess prostatectomy care, such as surgical margin rates and quality of life outcomes.

Second, our risk adjustment variables demonstrated appropriate relationships with postoperative events. A greater burden of comorbid illnesses conferred an increased likelihood of prolonged length of stay after nephrectomy and prostatectomy. Comorbidity is associated with medical and surgical complications after radical nephrectomy and prostatectomy, a predominant driver of length of stay outcomes.18, 19 Similarly, greater comorbidity typically increases patient risk for medical and surgical readmissions in the postoperative period, which was true for our patients undergoing urologic cancer surgery.20–22 As expected, older age was associated with higher event rates for all three procedures.

Third, complications attributed to AHRQ PSI flags were rare. Thromboembolic events, although infrequent, were the most common PSI identified. Within 30 days of surgery, thromboembolic events occurred in 4% of cystectomy patients, 1% of nephrectomy patients, and less than 1% of prostatectomy patients. Patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer often carry multiple risk factors that render them in the highest risk category for thromboembolic events after surgery: cancer, older age, pelvic surgical site.23, 24 Guidelines from the American Urological Association recommend combination prophylaxis for cystectomy patients,23 which has been shown to reduce event rates to 0–2% after radical cystectomy.25, 26 Statewide rates exceeding 2% suggest misuse of thromboprophylaxis after cystectomy across a range of urologic practice settings. Wound dehiscence was significantly more common after radical cystectomy than after nephrectomy or prostatectomy, likely related to the longer surgical time, increased complexity of the patient case mix, and the intra-abdominal approach required for bowel surgery for the urinary diversion.27

Fourth, readmissions were much more common after cystectomy than after nephrectomy or prostatectomy. More than one-third of cystectomy patients were readmitted for medical or surgical care within 90 days of surgery, compared with 13% of nephrectomy patients and less than 5% of prostatectomy patients. These results corroborate the high burden of readmissions after cystectomy seen in Medicare data.21 Compared with nephrectomy and prostatectomy, the need for reconstruction following extirpation confers an exceptional burden of medical and surgical considerations that increase the postoperative stay and convalescence after radical cystectomy. Readmission rates did not vary substantially by hospital, possibly indicative of the pronounced regionalization of cystectomy care: 30% of cystectomies statewide occur at the 2 highest volume hospitals. Likewise, this complex surgery and its associated patient population may simply carry an inherent risk of medical and surgical readmissions. Understanding the factors associated with post-cystectomy readmissions may help reduce these rates along with the personal and economic burden of cystectomy care.

Fifth, as reports of urologic cancer surgery results have consistently corresponded to volume-outcomes relationships,9, 28, 29 the poor-performing high volume hospitals that we identified may represent poor risk adjustment rather than outliers in quality of surgical care. The lack of cancer-specific information, as noted above regarding length of stay outcomes after nephrectomy, clearly affects outcomes for the highest volume centers. This may be particularly relevant to cancers with heterogeneity in surgical difficulty corresponding to heterogeneity in cancer severity. Similarly, the inability to adjust for other variables that affect surgical complexity may limit our ability to benchmark surgical outcomes from our data. Risk adjustment for hospital and provider-specific outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting typically relies on a multitude of variables that account for the acuity of the patient.14, 30 A surgical collaborative that allows capture of these important variables, often not available in claims data, would allow for detailed risk adjustment algorithms. The Surgical Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) has achieved measurable improvements in the quality of general surgical care in Washington State through such collaboration.31 Detailed abstraction forms capture patient comorbidity, patient acuity, surgical processes of care, and postoperative management variables and are used to benchmark outcomes after elective colon surgery.32 A urological SCOAP would facilitate better exploration of the quality of care delivered at hospitals to more accurately capture outcomes after urologic surgery. Quality improvement initiatives with urological SCOAP as a substrate could target the identified heterogeneity in surgical outcomes. For example, dissemination of clinical care pathways to participating hospitals might address the marked variation in length of stay outcomes identified in our analysis after radical nephrectomy and prostatectomy.

Our study has numerous limitations which should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, we assigned comorbidity based on the index hospital admission, which may underestimate the burden of other health conditions. However, our inability to access outpatient claims would potentially cause an algorithm including antecedent admissions to disproportionately assign comorbidity for the sicker patients more prone to pre-index hospitalizations. Second, we understand that the AHRQ PSIs may underestimate the occurrence of these events in our sample as many postoperative PSIs are amenable to outpatient management. Despite this limitation, we did demonstrate a quality concern in the potentially excessive rate of thromboembolic events after radical cystectomy. Third, given that many hospitals had low surgical volumes, especially for radical cystectomy, our analysis may fail to capture clinically meaningful differences in the quality of urologic care among hospitals. The lack of statistical significance may relate more to the underpowering effect of low surgical volumes rather than true clinical equivalence of surgical outcomes. Fourth, our data was restricted to patients who received their surgical and postoperative care in Washington State. We would not have captured patients who received their surgical care in Washington, but returned home for their convalescent care. This would have most affected our readmissions outcomes. This may also decrease the generalizability of our results: care in Washington State does not necessarily extrapolate to care elsewhere throughout the US, where demographics, payer mix, urologist penetration, and other important patient and provider characteristics may differ. Finally, as discussed above, our study of outcomes after cancer surgery lacked cancer-specific information. Although we were able to discriminate outlier hospitals for certain outcomes with the crude risk adjustment our data afforded, detailed cancer-specific information would confer better adjustment that may alter the results presented.

Despite these limitations, we identified substantial hospital-specific variation in outcomes after urological cancer surgery. The hospital at which patients receive their urological cancer care remains an important determinant of their outcomes. Length of stay after nephrectomy and prostatectomy were particularly prone to variation at the hospital-level. A urological collaborative with transparent process and outcomes reporting might facilitate better risk adjustment and provide a forum for quality improvement to address the identified variations in surgical quality of care.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grant UL1RR025014 from the NIH National Center for Research Resources. This material is also the result of work supported in part by resources from the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, Washington.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dodgion CM, Greenberg CC. Using Population-Based Registries to Study Variations in Health Care. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(6):319–320. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Dartmouth atlas of health care, 1999. Chicago Ill.: American Hospital Publishing; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krupski TL, Kwan L, Afifi AA, Litwin MS. Geographic and socioeconomic variation in the treatment of prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7881–7888. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu-Yao GL, McLerran D, Wasson J, Wennberg JE. An assessment of radical prostatectomy. Time trends, geographic variation, and outcomes. The Prostate Patient Outcomes Research Team. Jama. 1993;269(20):2633–2636. doi: 10.1001/jama.269.20.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gore JL, Litwin MS, Lai J, Yano EM, Madison R, Setodji C, et al. Use of radical cystectomy for patients with invasive bladder cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(11):802–811. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller DC, Saigal CS, Banerjee M, Hanley J, Litwin MS. Diffusion of surgical innovation among patients with kidney cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(8):1708–1717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller DC, Saigal CS, Warren JL, Leventhal M, Deapen D, Banerjee M, et al. External validation of a claims-based algorithm for classifying kidney-cancer surgeries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:92. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, Brennan MF. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. Jama. 1998;280(20):1747–1751. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, Kattan MW, Schrag D, Warren JL, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1138–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollenbeck BK, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. Volume, process of care, and operative mortality for cystectomy for bladder cancer. Urology. 2007;69(5):871–875. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu JC, Gold KF, Pashos CL, Mehta SS, Litwin MS. Role of surgeon volume in radical prostatectomy outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(3):401–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romano PS, Geppert JJ, Davies S, Miller MR, Elixhauser A, McDonald KM. A national profile of patient safety in U.S. hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(2):154–166. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahian DM, Torchiana DF, Shemin RJ, Rawn JD, Normand SL. Massachusetts cardiac surgery report card: implications of statistical methodology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(6):2106–2113. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniels MJ, Gatsonis C. Hierarchical polytomous regression models with applications to health services research. Stat Med. 1997;16(20):2311–2325. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971030)16:20<2311::aid-sim654>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low RB, Ito S, Gregory R, Wu J, Dunn V, Jacobs C, et al. Using the GLIMMIX Procedure to Model Hospital Quality Measured by CMS: Comparing the City-Owned Hospitals, Other Safety Net Hospitals, and Hospitals for the Well Insured. SAS Global Forum 2010. 2010;2010(Paper 164):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis : an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London; Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joudi FN, Allareddy V, Kane CJ, Konety BR. Analysis of complications following partial and total nephrectomy for renal cancer in a population based sample. J Urol. 2007;177(5):1709–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner TA, Bissonette EA, Petroni GR, McClain R, Sokoloff MH, Theodorescu D. Surgical and postoperative factors affecting length of hospital stay after radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2000;89(2):424–430. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000715)89:2<424::aid-cncr30>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stimson CJ, Chang SS, Barocas DA, Humphrey JE, Patel SG, Clark PE, et al. Early and late perioperative outcomes following radical cystectomy: 90-day readmissions, morbidity and mortality in a contemporary series. J Urol. 2010;184(4):1296–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gore JL, Lai J, Gilbert SM. Readmissions in the postoperative period following urinary diversion. World J Urol. 2011;29(1):79–84. doi: 10.1007/s00345-010-0613-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Walraven C, Dhalla IA, Bell C, Etchells E, Stiell IG, Zarnke K, et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–557. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forrest JB, Clemens JQ, Finamore P, Leveillee R, Lippert M, Pisters L, et al. AUA Best Practice Statement for the prevention of deep vein thrombosis in patients undergoing urologic surgery. J Urol. 2009;181(3):1170–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Samama CM, Lassen MR, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S–453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang SS, Cookson MS, Baumgartner RG, Wells N, Smith JA., Jr Analysis of early complications after radical cystectomy: results of a collaborative care pathway. J Urol. 2002;167(5):2012–2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koya MP, Manoharan M, Kim SS, Soloway MS. Venous thromboembolism in radical prostatectomy: is heparinoid prophylaxis warranted? BJU Int. 2005;96(7):1019–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoenberg MP, Gonzalgo ML. Management of Invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006. pp. 2468–2478. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaishampayan UN, Do H, Hussain M, Schwartz K. Racial disparity in incidence patterns and outcome of kidney cancer. Urology. 2003;62(6):1012–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollenbeck BK, Ye Z, Dunn RL, Montie JE, Birkmeyer JD. Provider treatment intensity and outcomes for patients with early-stage bladder cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(8):571–580. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Health NYSDo., editor. Adult cardiac surgery in New York state, 2006–2008. Albany, NY: New York State Department of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuschieri J, Florence M, Flum DR, Jurkovich GJ, Lin P, Steele SR, et al. Negative appendectomy and imaging accuracy in the Washington State Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):557–563. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318187aeca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flum DR, Fisher N, Thompson J, Marcus-Smith M, Florence M, Pellegrini CA. Washington State's approach to variability in surgical processes/Outcomes: Surgical Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) Surgery. 2005;138(5):821–828. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]