Abstract

Mycobacteriophage Bxb1 encodes a serine-integrase that catalyzes both integrative and excisive site-specific recombination. However, excision requires a second phage-encoded protein, gp47, which serves as a recombination directionality factor (RDF). The viability of a Bxb1 mutant containing an S153A substitution in gp47 that eliminates the RDF activity of Bxb1 gp47 shows that excision is not required for Bxb1 lytic growth. However, the inability to construct a Δ47 deletion mutant of Bxb1 suggests that gp47 provides a second function that is required for lytic growth, although the possibility of an essential cis-acting site cannot be excluded. Characterization of a mutant prophage of mycobacteriophage L5 in which gene 54 – a homologue of Bxb1 gene 47 – is deleted shows that it also is defective in induced lytic growth, and exhibits a strong defect in DNA replication. Bxb1 gp47 and its relatives are also unusual in containing conserved motifs associated with a phosphoesterase function, although we have not been able to show robust phosphoesterase activity of the proteins, and amino acid substitutions with the conserved motifs do not interfere with RDF activity. We therefore propose that Bxb1 gp47 and its relatives provide an important function in phage DNA replication that has been co-opted by the integration machinery of the serine-integrases to control the directionality of recombination.

Keywords: Phage integration, Directionality control, Bacteriophage

Introduction

Mycobacteriophage Bxb1 is a temperate phage that infects and forms lysogens of Mycobacterium smegmatis, a nonpathogenic relative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bxb1 is one of a large collection of over 80 completely sequenced mycobacteriophage genomes encompassing a large span of genetic diversity (Pope et al., 2011). Although eleven of these encode large serine recombinases, Bxb1 is the only one of the mycobacteriophage serine integrases to be investigated in depth (Ghosh et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2003; Ghosh et al., 2005; Ghosh et al., 2006b; Ghosh et al., 2008), along with that encoded by the M. tuberculosis prophage-like element, φRv1(Bibb and Hatfull, 2002; Bibb et al., 2005).

The phage-encoded large serine-integrases are of interest because they function catalytically like other serine-recombinases – with concerted cleavage of both DNA strands and covalent linkage to an active site serine residue (Smith and Thorpe, 2002; Ghosh et al., 2003; Grindley et al., 2006) – but without requirement for DNA supercoiling, accessory protein binding sites, or secondary host factors. The attP and attB sites are relatively simple – typically less than 50 bp – with the crossover site centrally located and flanked by imperfect inverted repeats. For mycobacteriophage Bxb1, regulation of directionality is strongly regulated and is dependent on a second phage-encoded protein, Bxb1 gp47 (Ghosh et al., 2006b). In its absence, integration proceeds efficiently with just Bxb1 integrase (gpInt) and short DNA substrates containing attP and attB (Ghosh et al., 2003), but no excision is observed. If Bxb1 gp47 is present, then integrative recombination is inhibited and gpInt mediates excisive recombination between attL and attR.

Bxb1 gp47 is an unusual recombination directionality factor (RDF) in that it is unrelated to Xis proteins that work with tyrosine-integrases (Lewis and Hatfull, 2001) and does not bind by itself directly to attachment site DNA, but associates with integrase-DNA complexes (Ghosh et al., 2006b). Interestingly, directionality control of Streptomyces phage φC31 integrase is determined similarly, although the phage-encoded protein, gp3 is evolutionarily unrelated to Bxb1 gp47 (Khaleel et al., 2011). RDF proteins have also been described for the φRv1 and TP901 serine-integrases (Breuner et al., 1999; Bibb et al., 2005) although these are small basic proteins, and related to the Xis proteins usually associated with tyrosine integrases. DNA binding is not required for Bxb1 gp47, φC31 gp3, or the φRv1RDF (Bibb et al., 2005; Ghosh et al., 2006b; Khaleel et al., 2011), and although they have distinct evolutionary origins, they may act similarly to modulate the configuration of integrase-DNA complexes such as to modulate substrate-dependent protein-mediated synapsis.

Seventeen of the currently sequenced mycobacteriophages encode relatives of Bxb1 gp47 (Fig. 1), but the locations, structures, and distributions among the different genes are unusual. First, in Bxb1, gene 47 is not located proximal to the attP site and integrase gene, but displaced approximately 5 kbp to their right, among genes that have putative roles in DNA replication, including a DNA Polymerase and a DNA Primase; it is similarly located in all other ten mycobacteriophages that encode a serine recombinase. Secondly, homologues of Bxb1 gp47 are present in six mycobacteriophages that do not encode a serine-integrase, all of which encode a tyrosine-integrase. The site-specific recombination system of one of these – L5 – has been studied extensively, and all of the components required for efficient integrative and excisive recombination have been identified (Lee and Hatfull, 1993; Lewis and Hatfull, 2000); the L5 gp54 homologue of Bxb1 gp47 is not among them. Lastly, three of the 17 homologues of Bxb1 gp47 – all within serine-integrase encoding genomes, U2, Bethlehem and KBG – contain inteins. Inteins are typically associated with genes required for essential functions (Cheriyan and Perler, 2009), and prophage excision is not typically required for lytic phage propagation of infecting particles. This raises the question as to whether Bxb1 gp47 and its relatives are supporting some additional phage requirement, perhaps in DNA replication during lytic growth.

Figure 1. Amino acid sequence alignment of Bxb1 gp47 and related proteins.

Amino acid sequences of all 17 members of Pham 1558 were aligned using the default parameters in ClustalX. Three of the proteins contain an intein following the cysteine residue at position 95, and the intein sequences were deleted prior to alignment. The locations of four segments of well-conserved components (Motifs, I, II, II and V) of calcineurin-like phosphoesterases are boxed and the consensus residues are shown. The positions where mutations in Bxb1 gp47 were reported previously to inactivate the ability of Bxb1 gp47 to support excisive recombination are shown. The red arrow indicates the position of the S153A substitution in Bxb1 gp47.

Here we present evidence supporting a role for Bxb1 gp47 and its homologues in mycobacteriophage DNA replication, in addition to its RDF function. We show that the excision function of Bxb1 gp47 is not required for lytic growth, but that gp47 is likely essential for plaque formation. Furthermore, an L5 prophage in which its gp47 homologue is deleted is unable to undergo efficient lytic induction and exhibits a strong defect in DNA replication. Curiously, these unusual RDF proteins contain motifs associated with phosphoesterase (e.g. phosphatase) activity, although neither Bxb1 gp47 nor its L5 gp54 homologue shows robust phosphoesterase activity in vitro, and substitutions in putative metal coordinating residues do not interfere with excision activity. We propose that Bxb1 and its relatives act similarly in DNA replication and in recombination directionality control, by influencing the active conformations of protein-DNA complexes.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Media

M. smegmatis mc2155 was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium and Middlebrook 7H10 solid medium from Difco, supplemented with ADC and kanamycin as needed for selection of strains carrying plasmids for complementation studies. Middlebrook 7H9 medium was further supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80. E. coli DH5α and E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS (Invitrogen) were grown in LB broth or LB-agarose (Difco) supplemented as needed with antibiotics for selection. 2.0% D-glucose was added to LB broth for expression of H6-MBP-gp47 protein, as described below.

Plasmids

Plasmid pLC3 is a modified form of the expression vector pET-28d (Novagen) with a Maltose Binding Protein (MBP)-coding region inserted into the multiple cloning site (MCS). pGEX-2T was obtained from GE LifeSciences. The plasmids pPGX6b, pPGX7 and pPGX8 contain M. smegmatis origins of replication and encode promoterless Bxb1 gp47, L5 gp54, and L5 proteins gp53 – gp55, respectively. Plasmid pAIK6 contains a 50-bp attP site (Kim et al., 2003).

Cloning and Subcloning

pPGgp47 was produced by PCR amplification of gp47 from Bxb1 genomic DNA with added Nde1 and Xho1 sites (Ghosh et al., 2006a). Plasmid pLC3-gp47 and derivatives (wild-type gp47 and variants) were produced by subcloning from plasmid pET28c into pLC3. Plasmid pGEX-2T-gp47 was produced by PCR amplification of gp47 with flanking HindIII and Nde1 sites and digested with these enzymes, then ligated into digested pGEX-2T vector (GE LifeSciences).

PCR Mutagenesis

Plasmid pPGgp47 variants containing mutations in Motifs I, II, II, V were produced by QuickChange PCR mutagenesis (Stratagene). Predicted metal-chelating residues were targeted in each motif.

Recombinant Protein Over-Expression and Purification

BL21(DE3)pLysS cells were transformed with the desired plasmid, grown to OD (600 nm) = 0.6 at 30°C, induced with 0.6 mM IPTG and grown for an additional 4 hrs at 22°C. Wild type and mutant His6-gp47 were purified as described previously (Ghosh et al., 2006a).

Bxb1 Integrase-H6 was purified by nickel affinity chromatography with an Ni-NTA resin as described previously (Kim et al., 2003). Bxb1 gp47-GST was overexpressed from recombinant plasmid pGEX-2T-gp47 and purified according to the recommended procedure for GST fusions from the supplier (GE Healthcare. Affinity Chromatography: Principles and Methods).

For purification of His6-MBP-gp47, the clarified lysate was incubated with ~2 mL amylose resin (Qiagen) for 1–2 h at 4° C and the mixture was loaded onto a disposable column. The resin was washed with 20 column volumes of buffer containing 10mM Tris (pH 8.0), 300mM NaCl, 10% glucose. The fusion protein was eluted with 10 column volumes of the above buffer + 10 mM maltose.

Bacteriophage Recombineering by Electroporated DNA (BRED)

Mutagenesis of Bxb1 by BRED was performed as described earlier. (Marinelli et al., 2008). In the case of the point mutant Bxb1 gp47-S153A six generations of lytic propagation were required to obtain a sample of mutant, which appeared highly enriched in the desired mutant as per MAMA-PCR and was purely the desired mutant according to whole-genome sequencing. The gp47 deletion mutant was never detected in a total of ~1400 second-generation plaques screened by DADA-PCR.

Whole-Genome Sequencing of Mutant Bacteriophage DNA

Bxb1 gp47-S153A genomic DNA was extracted and then sequenced by Illumina Solexa sequencing technology on a Genome Analyzer IIx platform.

In vitro DNA Recombination Assays

In vitro recombination assays were performed as described previously (Ghosh et al., 2006a). Briefly, a circular DNA substrate (200 ng; ~3 nM final concentration) containing an attP or attL site (pAIK6, 5 kbp; pMOS-attL, 3 kbp) and a 60-bp linear DNA substrate (~4 nM final concentration) consisting of an attB or attR site were incubated in a reaction buffer (as described) together with varying concentrations of H6-gp47 and mutant H6-gp47; reactions were stopped by heat-killing of Integrase at 75° C for 15 min, and products and substrates resolved on a 0.8% agarose gel prior to visualization with ethidium bromide staining and UV exposure. Reaction progress was determined by comparing the intensities of scDNA plasmid bands to linearized recombination product DNA bands.

Phosphatase Activity Assays

We performed fluorimetric assays using the fluorigenic substrate fluorescein diphosphate (FDP). The assays are based on the commercial Sensolyte FDP Protein Phosphatase Kit from Anaspec (SensoLyte® FDP Protein Phosphatase Assay Kit). Reactions containing 100 µL total volume were performed following the manufacturer’s recommendations, with some modifications as noted below. Reaction mixtures containing FDP and a gp47 variant in the provided reaction buffer were incubated for some amount of time in a 96-well plate; Calf Intestinal Phosphatase (CIP) was used as a positive control, and 1 mg/mL BSA was added to all reactions. Divalent metals in the form MCl2 were added at various concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 50 mM. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 50 µL of the provided Stop Buffer from Anaspec.

Results

Bxb1 gp47 and related proteins contain phosphoesterase-like domains

When queried against databases of conserved domains, nine of the 17 Bxb1 gp47 related proteins (Jasper, Pukovnik, Che12, L5, D29, Redrock, Bxz2, Eagle and Peaches) return matches to calcineurin-like phosphoesterase (pfam00149) and metallophosphatase superfamily (cl13995) domains (Fig. 1). Two of the proteins (Peaches gp52 and Eagle gp52) also report a match to COG0420, a conserved domain associated with DNA repair proteins such as sbcD (Eykelenboom et al., 2008). It has been reported previously (Aravind and Koonin, 1998) that a variety of DNA Polymerase subunits found in bacteria, archaeal, and eukaryotic organisms also contain this putative calcineurin-like phosphoesterase domain. This domain typically contains five motifs (Motifs I – V), four of which are especially well conserved. It is proposed that these motifs contribute to the binding of metals such as manganese or zinc that are required for enzymatic activity. Alignment of Bxb1 gp47 and its relatives shows strong conservation of all four residues in motif III, the GHTH segment of motif V, the GDXXD segment of motif II, and the invariant aspartate residue in motif I (Fig. 1). We note that the positions of intein insertions (between residues 95 and 96 in U2, KBG and Bethlehem) lie between motifs III and V and are expected to interrupt functionality (Fig. 1). Finally, a search for structural similarities using HHPred revealed strongly significant matches to a large collection of metalloproteases and related proteins (24 hits with a 99% probability score or better). Interestingly, these include the DNA repair protein Mre11 (Stracker and Petrini, 2011) and M. tuberculosis Rv0805 (Podobnik et al., 2009).

Although Bxb1 gp47 and its relatives contain these phosphoesterase motifs, there are several reasons for questioning whether they play any role in recombination directionality control function. First, it is difficult to imagine what role a phosphatase-like activity could play in site-specific recombination, and there is no evidence for such events in other well-studied serine-recombinase systems. Secondly, we note that of the 14 mutants of Bxb1 gp47 isolated previously that are defective in supporting excisive recombination and contain single amino acid substitutions, only one maps within the conserved motifs; the thirteen others are distributed throughout other parts of the protein (Fig. 1). Third, Aravind and Koonin (1998) noted previously that in the alignment of DNA polymerases containing phosphoesterase domains that it is not uncommon to find substitutions that cause loss of essential catalytic residues, suggesting that these domains could play architectural rather than catalytic roles.

Bxb1 gene 47 is required for lytic growth

Because integration and excision are not anticipated to be required for lytic growth following infection, then if Bxb1 gp47 is solely required for excision then it should be dispensable for lytic growth. To test this we used a previously described method for high-efficiency mutagenesis of Bxb1 to construct a mutant deleting gene 47 (Marinelli et al., 2008). Following electroporation of Bxb1 genomic DNA and a 200 bp dsDNA substrate containing the deletion, primary plaques were screened by PCR, and one was identified that clearly contains both the wild-type and mutant alleles (Fig. 2). This method permits the recovery of the mutant allele even if the gene is essential because these primary plaques always contain wild-type phage particles, and there is the opportunity for complementation. However, when we re-plated and recovered individual plaques from the mixed primary plaque, we were not able to recover the deletion mutant, indicating strongly that gene 47 is required for lytic growth. Repeated attempts to recover the mutant from either single plaques or secondary lysates were all unsuccessful. Unfortunately, we were also not able to recover the deletion mutant by complementation. Failure to complement could be due to lack of gp47 expression at the appropriate level in infected cells, a requirement for a cis-acting site located within the gene 47 region, or from genetic polarity. Because the gene 47 deletion was designed to fuse the first and last twenty codons in-frame, the likelihood of complementation failure due to genetic polarity was minimized, but remains a possibility. We also note that we have encountered many other scenarios of failure to complement essential mycobacteriophage functions (our unpublished results), and the lack of gene 47 complementation therefore should be interpreted cautiously. These experiments are consistent with the hypothesis that gp47 plays a secondary role to its recombination directionality control activity, and that it is required for lytic growth.

Figure 2. The inability to delete Bxb1 gene 47 suggests it is required for lytic growth.

(A) Schematic representation of a segment of the Bxb1 genome showing the locations of the segments (thick horizontal bars) used to make the substrate to construct a gene 47 deletion. The positions of the primers, P1 and P2, used for plaque screening are shown; wild type Bxb1 is predicted to generate a 1.3 kbp product, and the deletion is predicted to yield a 0.55 kbp product. (B) Plaques recovered from BRED engineering of Bxb1 to introduce a deletion of gene 47 were screened by PCR to identify those containing both the mutant allele (indicated by arrow) and the wild-type product (wt); the additional band migrating below the wild-type product results from non-specific amplification. Two such primary plaques were identified (lanes 6 and 12). DNA size markers in kbp are indicated. (C) After replating a mixed plaque identified in panel B, individual plaques were screen again by PCR (lanes 1–10) but no mutant plaques were recovered. The mutant allele could also not be identified in a lysate recovered from pooling ~300 secondary plaques (lane 11). Control primary plaque (C) containing the mutant allele (arrow) is shown.

The RDF function of Bxb1 gp47 is not required for lytic growth

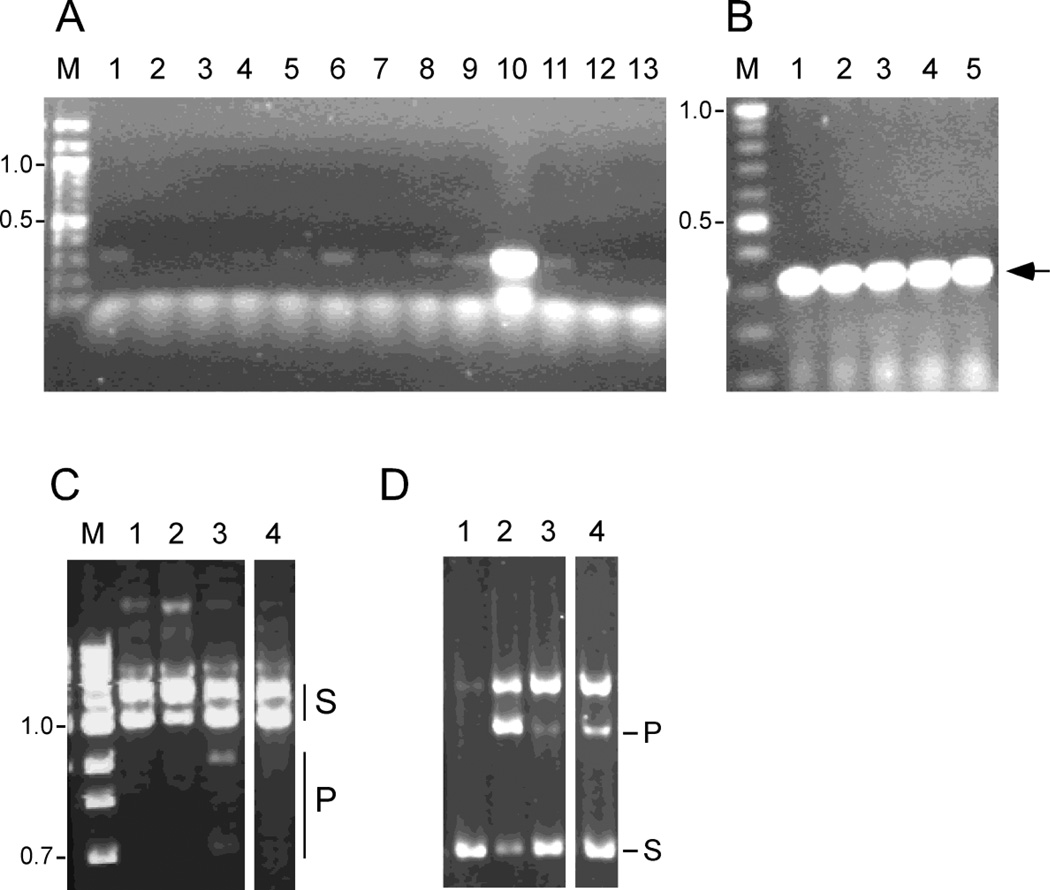

We previously described the isolation of mutant derivatives of Bxb1 gp47 that are defective in supporting excisive recombination (Ghosh et al., 2006b). To address the possibility that the inability to isolate a gene 47 deletion derivative of Bxb1 lies in an unexpected requirement of excisive recombination for lytic growth, we attempted to engineer one of these mutations (S153A) into the phage genome (Fig. 3). This substitution was chosen because the defect in the mutant protein is specific to its excision function, and the protein retains the ability to inhibit integrative recombination (Fig. 3). It is therefore not a simple loss of function substitution. Primary plaques containing the mutation were readily recovered (Fig. 3), and a plaque-purified mutant derivative was recovered from a secondary plating. This mutant is thus viable for lytic growth.

Figure 3. Isolation of a Bxb1 mutant containing an S153A substitution in gp47.

Individual plaques recovered from a BRED mutagenesis experiment designed to introduce an S153A substitution in Bxb1 gene 47 were screened by PCR to identify those containing the mutant allele (A). The plaque screened in lane 10 shows a strongly positive signal. Following further propagation plaque-purified mutants were isolated (B) containing the gene 47 mutation. The position of the PCR product generated from the mutant is shown by the arrow. The complete genome sequence of the mutant showed that there were no mutations introduced other than those conferring the S153A change in gp47. C. In vitro excisive recombination reactions were performed using a supercoiled attL substrate and a linear attR partner DNA. The products of the reaction were then cleaved with the restriction enzyme Xmn1. Lane 3 contains both gpInt and wild-type gp47; lanes 1–2 are controls lacking both gpInt and gp47 (lane 1), or lacking gp47 (lane 2). Lane four contains gpInt and gp47 S153A showing that the gp47 S153A mutant is defective in supporting excisive recombination. D. Integrative recombination reactions between a supercoiled DNA substrate (S) containing attP and a linear DNA fragment containing attB generates a linear recombinant product (P) showing that gp47 S153A retains the ability to inhibit integrative recombination. Products were not digested prior to electrophoresis. Lane 2 contains gpInt but not gp47; lane 1 is a control without gpInt. Lanes 3 and 4 contain gpInt and either wild-type gp47 or gp47 S153A respectively.

To confirm that the mutant is indeed defective in its support of excisive recombination the mutant gp47 protein was expressed and purified. In vitro recombination assays showed that it is strongly defective in support of excisive recombination, but that it retains its ability to inhibit integrative recombination (Fig. 3). We also constructed lysogens of the gp47 S153A mutant and showed that it confers a 5- to 10-fold lower level of spontaneous phage release than the wild-type phage, consistent with the idea that excision is required for productive lytic growth from a lysogen and that the S153A mutant is defective in excision. Furthermore, because this mutant could be readily recovered, it supports the conclusion that the failure to obtain a gene 47 deletion mutant is because the gene is essential for lytic growth.

L5 gene 54 is required for DNA replication

Lysogens of Bxb1 and other mycobacteriophages that have been tested are not readily inducible by mitomycin C (our unpublished observations). Because thermoinducible mutants of mycobacteriophage L5 have been described previously (Donnelly-Wu et al., 1993), we constructed a derivative of an L5 prophage in which its homologue of Bxb1 gene 47 – i.e. L5 gene 54 – is deleted. A gene replacement mutant was constructed by recombineering of an L5 thermoinducible lysogen such that a hygromycin resistance cassette replaces gene 54, and the hygromycin resistance marker was then removed by resolvase-mediated site-specific recombination, generating a small 120 bp genetic scar and minimizing the likelihood of genetic polarity.

Thermoinduction of the L5 Δ54 mutant strain resulted in approximately a 106-fold reduction in the number of phage particles produced, consistent with the conclusion that L5 gene 54 is required for lytic growth. We attempted to complement the defect by expressing L5 gp54 from a complementing plasmid, but were unsuccessful in doing so. To determine if the defect in propagation of the L5 Δ54 mutant results from a problem in DNA replication, we compared the amount of phage DNA in the wild-type and L5 Δ54 mutant strains following induction (Fig. 4). Four different loci were investigated, and in all cases a strong defect in DNA replication was observed. Similarly to the Bxb1 gene 47 deletion experiment, we were unable to complement the L5 Δ54 mutant and although the genetic modification is modest the possibility of polar effects on downstream gene expression cannot be completely eliminated. Nonetheless, these observations are consistent with the hypothesis that L5 gene 54 is required for L5 DNA replication during lytic growth.

Figure 4. L5 gp54 is required for phage DNA replication.

A mutant derivative of a thermoinducible mutant of L5 was constructed in which gene 54 is deleted, and the amounts of phage DNA following induction were determined by quantitative PCR. The increase in relative fluorescence with increasing cycle numbers are shown, and higher amounts of DNA yield greater fluorescence with fewer cycles of amplification. Four different primer sets were used corresponding to gene X (panel A), gene Y (panel B), attP (panel C) and gene XYZ (panel D). For each primer set the data from triplicate samples from induction of a wild-type L5 lysogen control (‘1’) and the Δ54 mutant (‘2’) are shown.

RDF activities of Bxb1 gp47 mutants

Because only one of the 17 point mutations in Bxb1 gene 47 defective in supporting excision described previously (Ghosh et al., 2006b) lies within a conserved motifs for phophoesterase activity (Fig. 1), it seems unlikely that conservation of these motifs is critical for RDF activity of gp47. To further investigate this we constructed mutants with either single or double amino acid substitutions in highly conserved residues in Motifs I (D10G), II (mutant 1: D41V; mutant 2: G40C/D41V), III (mutant 1: N92Y; mutant 2: G91A/N92Y) and V (H175D/H177D). These gp47 mutants were expressed (Fig. S1), purified, and tested for their ability to support excisive recombination and to inhibit integrative recombination (Fig. 5, data not shown). We observed that mutants in all four motifs both support excision and inhibit integration and are indistinguishable from the wild type protein in these assays. We note that although one of the 14 mutants isolated previously in a screen for excision-defective derivatives (T176A) maps within Motif V (Fig. 1), in vitro assays show that it has near-wild-type activity both in supporting excisive recombination and inhibiting integrative recombination (data not shown). There is therefore no obvious correlation between conservation of the motifs and RDF activity.

Figure 5. Excisive recombination by Bxb1 gp47 mutants.

A. Excision support by wild-type Bxb1 gp47. Excision reactions contained a 3.0 kbp supercoiled attL plasmid DNA, 60bp attR DNA, Bxb1 gpInt (63nM), and no gp47 (lane 1), 1.6µM gp47 (lane 2), and 3.3 µM gp47 (lane 3). Reaction products were not digested prior to electrophoresis. The positions of the substrate supercoiled attL DNA (S) and linear product (P) are shown. The 60bp attR substrate has migrated beyond the bottom of the gel picture. Markers are shown in kbp. B. Excision reactions containing gp47 D10G, with a substitution in the conserved motif I aspartic acid residue (see Fig. 1). Reactions were performed as in panel A but containing gp47 D10G as follows: none (lane 2), 1.5µM (lane 3), 3.3 µM (lane 4), 4.6 µM (lane 5). Lane 1 contains a no-integrase control.

Bxb1 gp47 and L5 gp54 do not have robust phosphatase activities

The property of the gp47 D10G mutant strongly suggests even if gp47 can function as a phosphoesterase, that the phosphoesterase activity is not required for recombination control. We have expressed and tested a variety of protein preparations – including those with a variety of different tags, the D10G and H175D/H177D mutants, and L5 gp54 – and failed to detect robust and reproducible hydrolysis of fluorescein diphosphate (FDP). The simple interpretation is that these RDF proteins lack phosphatase activity, although we cannot eliminate the possibilities that this results from poor expression (Fig. S1; we note that the RDF-active D10G mutant has higher levels of expression but did not have detectable phosphatase activity) or a preference for a different and undefined substrate for which it has high specificity.

Discussion

We have shown here that the Bxb1 gp47 recombination directionality factor plays dual roles in the life cycles of Bxb1. We were unable to delete gene 47 from the Bxb1 genome using an approach that requires plaque formation, suggesting that it is required for lytic growth, although we cannot exclude the possibility that there is a required cis-acting site within gene 47. In contrast a mutant containing a S153A substitution in gp47 was readily constructed and appears to have no obvious defect in plaque formation or lytic growth, even though the mutant protein is unable efficiently to support excisive recombination. The excision activity is thus not required for lytic growth as anticipated, and the failure to construct a gene 47 deletion mutant is not due to the inability to mutate this part of the Bxb1 genome. The conclusion that Bxb1 gp47 is required for lytic growth is consistent with the finding that it is conserved among mycobacteriophages that contain different types of integration systems that don’t require a gp47-like protein, and that some members of the protein family contain inteins. The likely role for this secondary function is in phage DNA replication during lytic growth, since an L5 mutant containing a deletion of its gene 54 homologue of Bxb1 47 is strongly defective in DNA replication.

We predict that all of the Bxb1 gp47-related proteins (Fig. 1) play a role in DNA replication, and that they serve an additional role in only those phages encoding a serine-integrase system. However, the serine integrases encoded by the mycobacteriophages fall into two main groups, in which those encoded by Bxz2 and Peaches are more distantly related to those of Bxb1, DD5, Lockley, SkiPole, Solon, U2, KBG, Bethlehem, and Jasper (Fig. S2). We therefore cannot assume that the Bxb1gp47–like proteins of Bxz2 and Peaches will necessarily play an RDF role in concert with their serine-integrases. If we suppose that Bxb1 and its relatives have co-opted the gp47-like proteins and adapted them for recombination directionality control it is plausible that the Bxz2 and Peaches have adopted alternative proteins for this purpose. We note that one of the phages encoding a Bxb1 gp47-like protein, Redrock, does not encode a site-specific recombinase at all, but instead encodes parAB genes at the same genomic location (Pope et al., 2011).

The presence of motifs that are strongly conserved among proteins related to calcineurin-like phosphoesterases raises the question as to whether gp47 and its close relatives contain a phosphoesterase function and if so whether it is needed for either recombinational control or DNA replication. Although we cannot eliminate the possibility that the gp47-like proteins have phosphoesterase activity, we have been unable to provide evidence to support this. We recognize that these proteins could possibly have strict substrate requirements that exclude simple substrates such as FDP, or that they require specific assay conditions that remains to be identified. However, the lack of a phosphoesterase activity is also not completely surprising because the previous analysis by Aravind and Koonin (1998) showed that similar domains are often found associated with DNA Polymerases, but in at least some members of this group, amino acid residues thought to be required for catalytic activity are altered. Because we have previously suggested that Bxb1 gp47 plays a role in remodeling the conformations of protein-DNA architectures in site-specific recombination, we suggest that it plays a similar role in determining the architectures of protein-DNA complexes during phage DNA replication.

Finally, we note that the multifunctional usage of RDF proteins is emerging as a common theme. Although the putative secondary function of the newly identified φC31 RDF has yet to be determined, its genomic location and expression pattern suggest that it may serve a role other than in directionality control (Khaleel et al., 2011). In the case of the φRv1 and TP-901 systems (Breuner et al., 1999; Bibb et al., 2005), although the RDFs are related to Xis proteins of the tyrosine integrases, it is plausible that they act similarly to the Bxb1 and φC31 RDFs by modulating synapsis without DNA binding and bending. These may have thus evolved relatively recently from RDFs associated with tyrosine integrases, and because the φRv1 RDF retains DNA binding activity (L. Bibb and GFH, unpublished observations), it could retain the ability to regulate other tyrosine integrases. Finally, we note that the Cox proteins of P2 and HP1 act not only in control of their tyrosine integrases but also in regulation of the phage life cycles (Yu and Haggard-Ljungquist, 1993; Esposito and Scocca, 1994).

Highlights.

The RDF (gp47) for the Bxb1 serine-integrase has sequence similarity to phophoesterases

Bxb1 gene 47 is required for lytic growth

Bxb1 gp47 is proposed to play a secondary role in phage DNA replication

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This was supported by NIH grant AI059114 to GFH. We thank Christina Ferreira for excellent technical support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aravind L, Koonin EV. Phosphoesterase domains associated with DNA polymerases of diverse origins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3746–3752. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.16.3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb LA, Hancox MI, Hatfull GF. Integration and excision by the large serine recombinase phiRv1 integrase. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1896–1910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb LA, Hatfull GF. Integration and excision of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis prophage-like element, phiRv1. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1515–1526. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuner A, Brondsted L, Hammer K. Novel organization of genes involved in prophage excision identified in the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7291–7297. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7291-7297.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheriyan M, Perler FB. Protein splicing: A versatile tool for drug discovery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:899–907. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly-Wu MK, Jacobs WR, Jr, Hatfull GF. Superinfection immunity of mycobacteriophage L5: applications for genetic transformation of mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:407–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito D, Scocca JJ. Identification of an HP1 phage protein required for site-specific excision. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:685–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eykelenboom JK, Blackwood JK, Okely E, Leach DR. SbcCD causes a double-strand break at a DNA palindrome in the Escherichia coli chromosome. Mol Cell. 2008;29:644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Bibb LA, Hatfull GF. Two-step site selection for serine-integrase-mediated excision: DNA-directed integrase conformation and central dinucleotide proofreading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3238–3243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711649105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Kim AI, Hatfull GF. The orientation of mycobacteriophage Bxb1 integration is solely dependent on the central dinucleotide of attP and attB. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Pannunzio NR, Hatfull GF. Synapsis in phage Bxb1 integration: selection mechanism for the correct pair of recombination sites. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:331–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Wasil LR, Hatfull GF. Control of phage Bxb1 excision by a novel recombination directionality factor. PLoS Biol. 2006a;4:e186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Wasil LR, Hatfull GF. Control of Phage Bxb1 Excision by a Novel Recombination Directionality Factor. PLoS Biol. 2006b;4:e186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindley ND, Whiteson KL, Rice PA. Mechanisms of site-specific recombination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:567–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleel T, Younger E, McEwan AR, Varghese AS, Smith MC. A phage protein that binds phiC31 integrase to switch its directionality. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:1450–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AI, Ghosh P, Aaron MA, Bibb LA, Jain S, Hatfull GF. Mycobacteriophage Bxb1 integrates into the Mycobacterium smegmatis groEL1 gene. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:463–473. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Hatfull GF. Mycobacteriophage L5 integrase-mediated site-specific integration in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6836–6841. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6836-6841.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Hatfull GF. Identification and characterization of mycobacteriophage L5 excisionase. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:350–360. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Hatfull GF. Control of directionality in integrase-mediated recombination: examination of recombination directionality factors (RDFs) including Xis and Cox proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2205–2216. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.11.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli LJ, Piuri M, Swigonova Z, Balachandran A, Oldfield LM, van Kessel JC, Hatfull GF. BRED: a simple and powerful tool for constructing mutant and recombinant bacteriophage genomes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podobnik M, Tyagi R, Matange N, Dermol U, Gupta AK, Mattoo R, Seshadri K, Visweswariah SS. A mycobacterial cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase that moonlights as a modifier of cell wall permeability. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32846–32857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope WH, Jacobs-Sera D, Russell DA, Peebles CL, Al-Atrache Z, Alcoser TA, Alexander LM, Alfano MB, Alford ST, Amy NE, Anderson MD, Anderson AG, Ang AAS, Ares M, Jr, Barber AJ, Barker LP, Barrett JM, Barshop WD, Bauerle CM, Bayles IM, Belfield KL, Best AA, Borjon A, Jr, Bowman CA, Boyer CA, Bradley KW, Bradley VA, Broadway LN, Budwal K, Busby KN, Campbell IW, Campbell AM, Carey A, Caruso SM, Chew RD, Cockburn CL, Cohen LB, Corajod JM, Cresawn SG, Davis KR, Deng L, Denver DR, Dixon BR, Ekram S, Elgin SCR, Engelsen AE, English BEV, Erb ML, Estrada C, Filliger LZ, Findley AM, Forbes L, Forsyth MH, Fox TM, Fritz MJ, Garcia R, George ZD, Georges AE, Gissendanner CR, Goff S, Goldstein R, Gordon KC, Green RD, Guerra SL, Guiney-Olsen KR, Guiza BG, Haghighat L, Hagopian GV, Harmon CJ, Harmson JS, Hartzog GA, Harvey SE, He S, He KJ, Healy KE, Higinbotham ER, Hildebrandt EN, Ho JH, Hogan GM, Hohenstein VG, Holz NA, Huang VJ, Hufford EL, Hynes PM, Jackson AS, Jansen EC, Jarvik J, Jasinto PG, Jordan TC, Kasza T, Katelyn MA, Kelsey JS, Kerrigan LA, Khaw D, Kim J, Knutter JZ, Ko C-C, Larkin GV, Laroche JR, Latif A, et al. Expanding the Diversity of Mycobacteriophages: Insights into Genome Architecture and Evolution. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MC, Thorpe HM. Diversity in the serine recombinases. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:299–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker TH, Petrini JH. The MRE11 complex: starting from the ends. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:90–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu A, Haggard-Ljungquist E. Characterization of the binding sites of two proteins involved in the bacteriophage P2 site-specific recombination system. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1239–1249. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1239-1249.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.