Abstract

The reduction in EPR signal intensity of nitroxide spin-labels by ascorbic acid has been measured as a function of time to investigate the immersion depth of the spin-labeled M2δ AChR peptide incorporated into a bicelle system utilizing EPR spectroscopy. The corresponding decay curves of n-DSA (n = 5, 7, 12, and 16) EPR signals have been used to (1) calibrate the depth of the bicelle membrane and (2) establish a calibration curve for measuring the depth of spin-labeled transmembrane peptides. The kinetic EPR data of CLS, n-DSA (n = 5, 7, 12, and 16), and M2δ AChR peptide spin-labeled at Glu-1 and Ala-12 revealed excellent exponential and linear fits. For a model M2δ AChR peptide, the depth of immersion was calculated to be 5.8 Å and 3 Å for Glu-1, and 21.7 Å and 19 Å for Ala-12 in the gel-phase (298 K) and Lα-phases (318 K), respectively. The immersion depth values are consistent with the pitch of an α–helix and the structural model of M2δ AChR incorporated into the bicelle system is in a good agreement with previous studies. Therefore, this EPR time-resolved kinetic technique provides a new reliable method to determine the immersion depth of membrane-bound peptides, as well as, explore the structural characteristics of the M2δ AChR peptide.

Keywords: Immersion depth, M2δ acetylcholine receptor, EPR spectroscopy, bicelle, transmembrane peptide, kinetics, ascorbic acid

1. Introduction

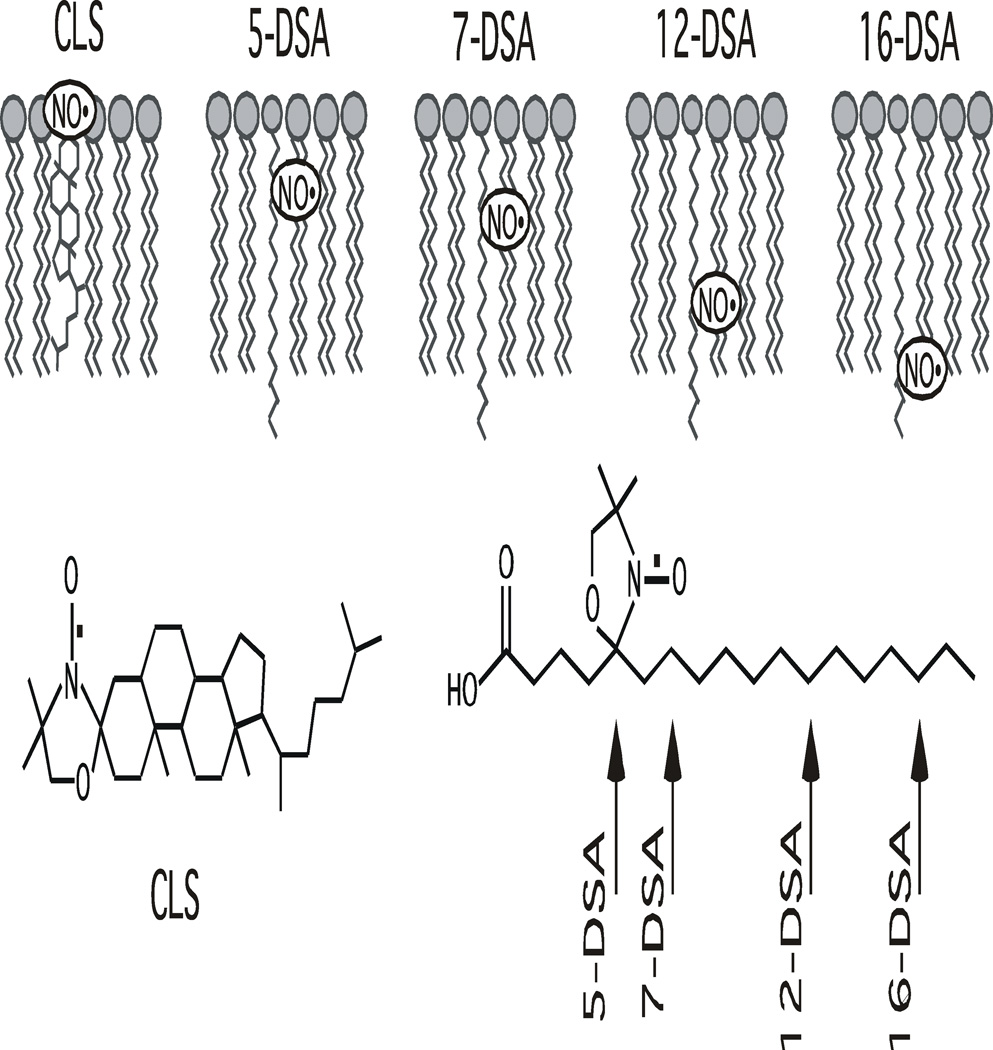

Membrane-bound proteins are known to play important roles in controlling physiological function in organisms. Immersion depth studies are critical to our understanding of the three dimensional structure of membrane proteins and peptides and, thus, provides important insights into the function of these molecules [1]. Membrane immersion depth is commonly determined by neutron diffraction techniques, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) spectroscopy, parallax analysis of fluorescence quenching by spin-labels, and collision gradient and rotational correlation time methods utilizing electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy [1–11]. In this paper, an alternative approach has been used to explore the immersion depth of membrane-bound proteins utilizing EPR spectroscopy. A reliable new bicelle technique is presented to determine the membrane immersion depth of single site spin-labeled peptide or proteins by EPR spectroscopy. To demonstrate the applicability of this method a highly studied transmembrane peptide M2δ, of the pentameric transmembrane protein (α2βγδ) AChR was used [12–14]. The method is based on kinetic analysis of the reaction of the ascorbic acid molecule with the paramagnetic nitroxide group of a spin probe incorporated into phospholipid bilayers. The structures of various spin-labels, cholestane (CLS) and n-doxylstearic acids (n-DSA; n = 5, 7, 12, or 16), were used in this study and the relative locations of their nitroxide moieties within the phospholipid bilayers are characterized in Figure 1. Ascorbic acid permeates into the phospholipid bilayers subsequent to its addition into the membrane sample and gradually reduces the bilayer embedded paramagnetic nitroxides into diamagnetic hydroxylamines [15, 16]. Direct analysis of the kinetics of reduction of these spin-labels and the corresponding rate constants is exploited to establish a calibration curve to probe the immersion depth of specific residues of spin-labeled transmembrane M2δ AChR peptide.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of CLS, 5-DSA, 7-DSA, 12-DSA, and 16-DSA spin-labels used in this study and the relative locations of their nitroxide moieties (NO˙) within the phospholipid bilayers. The arrow indicates the position of the doxyl labels attached to the acyl chain of the stearic acid.

At physiological pH value, taking into account the pK1 and pK2 values of ascorbic acid, this study reveals that the oxidation-reduction reaction between the nitroxide group and ascorbate ion in the bicelle system obey a first order rate law. If the reaction is simple and limited by diffusion of ascorbate from the aqueous partition to the inner part of the membrane, with the nitroxide localized in the later, its kinetics will be zero order with respect to the nitroxide. The data analysis of this rate law is not always straightforward, as the reaction is also known to be an overall second order reaction in other studies. The order of chemical reaction is complicated by several factors such as, permeability, composition of the membrane system, pH, type of nitroxide, mode of preparation, and temperature.[17]

In this report, we examine the immersion depth of membrane-bound rigid spin-labeled M2δ AChR utilizing kinetic measurement X-band EPR spectroscopy, in order to explore the structural characteristics of the transmembrane segment of the receptor into the bicelle system. The kinetic method employed in this work provides a novel and accurate method to determine the immersion depth of site-specific residues of membrane-bound peptides. The kinetic measurement EPR bicelle method is pertinent due to the good agreement between the proposed structural model of M2δ AChR using a different biophysical methods.

2. Methods

2.1 Materials

Fmoc amino acids and other chemicals for peptide synthesis were purchased from Applied Biosystems Inc. (Forster City, CA), 1, 2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), 1, 2–Dihexanoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (DHPC), and 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoetholamine-N-[poly(ethylene glycol) 2000] (PEG2000) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. HEPES (N-[2-hydroxy-ethyl] piperazine-N-2-ethanesulfonic acid), trifluoro acetic acid (TFA), 2, 2, 2-trifluoroethanol (TFE), CLS, 5-DSA, and 16-DSA were purchased from Sigma/Aldrich. 7-DSA was purchased from ICN. 12-DSA and (MTSSL) were obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals Inc. The cholesterol was obtained from Avocado Research Chemicals, Ltd. All lipids, cholesterol, and spin-labels were dissolved in chloroform and stored at −20°C prior to use. Ascorbic acid was purchased from Fisher Scientific. Aqueous solutions of ascorbic acid prepared fresh each day. All aqueous solutions were prepared with deuterium-depleted water purchased from Isoec Inc. (Miamisburg, OH). Double distilled water can alternately be used to prepare these solutions.

2.2 Peptide Synthesis of M2δ AChR synthesis

Solid-phase peptide synthesis using Fmoc-protection strategy was performed on a 433A peptide synthesizer from Applied Biosystems Inc. (Foster city, CA) to synthesize the model membrane peptides A12C M2δ AChR and TOAC1 M2δ AChR ([1] SL-M2δ AChR). The peptide synthesizer was equipped with a UV detector (wavelength set to 301 nm) to monitor the Fmoc removal from the N-terminus of the growing peptide. The FastFmoc chemistry-0.1 mmol protocol provided in the SynthAssist 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems Inc.) was modified by our lab to optimize the yield of the synthesis and allow for customized functionality [18]. An appropriate amount of Fmoc-Arginine(pbf)-NovaSyn TGA resin (substitution number = 0.22 g resin/mmol peptide) was used to synthesize 0.1 mmol of peptide (based on a theoretical yield of 100%). All amino acids were purchased as Fmoc-protected with chemically sensitive side-chain residues being chemically modified (side-chain protected) to minimize any side reactions. Synthesized peptides were removed from the synthesizer and cleaved from the resin. The spin-labeled [1] SL-M2δ AChR peptides were treated with NH3 (aq) to reoxidize the spin-label back to the nitroxide form, because TFA from the cleavage mixture reduces nitroxides to the hydroxylamine form. The Fmoc-TOAC synthesis was reformed according to published procedures [19, 20]. The α–helical M2δ transmembrane segment of AChR consists of 23 amino acid residues and has the following amino acid sequence:

(NH2-E1K2M3S4T5A6I7S8V9L10L11A12Q13A14V15F16L17L18L19T20S21Q22R23-COOH).

The amino acids underlined represent the spin-labeled sites used in this study.

2.3 Peptide Purification

The peptides (A12C M2δ AChR, [1] SL-M2δ AChR, and [12] SL-M2δ AChR) were purified on an Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AKTA Explorer 10S HPLC controlled by Unicorn version 3 system software. A C4 protein column (214TP104, 10 µm, 300 Å pore size, 0.46 × 25 cm, column volume of 4.15 mL) from Grace-Vydacc was used to purify the peptides. A 1 mL aliquot of the (5 mg/mL) peptide sample was injected into the column, and the peptide elution was achieved with a linear gradient to a final solvent composition of 95% of solvent B at a flow rate of 8 mL/min. The purified peptide fraction was lyophilized and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The lyophilized M2δ AChR peptide was dissolved in TFE and centrifuged to eliminate insoluble particles. The column was equilibrated with 90% solvent A/10% solvent B. Solvent A consisted of H2O and 0.1% TFA and solvent B was 80% IPA, 20% H2O, and 0.1% TFA. The lyophilized [1] SL-M2δ AChR peptide was dissolved in 5% HFIP, 50% n-propanol, and 45% H2O (at a concentration of 5 mg/mL). The column was equilibrated with 90% solvent A/10% solvent B. Solvent A consisted of H2O and 0.1% TFA and solvent B was 50% npropanol, 30% ACN, 20% H2O, and 0.1% TFA. The lyophilized [12] SL-M2δ AChR peptide was dissolved in methanol (at a concentration of 5 mg/mL). The column was equilibrated with 80% solvent A/20% solvent B. Solvent A consisted of H2O and 0.1% TFA and solvent B was 60% n-propanol, 30% ACN, 10% H2O, and 0.1% TFA.

2.4 MTSSL spin-labeling reaction

The synthesized and purified A12C M2δ AChR segment was labeled with the MTSSL spin-label through the following procedure. A 2.0 µmol purified A12C M2δ AChR peptide was dissolved in 300 µL DMSO solvent. Then, 10-fold excess of MTSSL was added and the coupling reaction was allowed to proceed for 48 hours at room temperature. The labeled peptides were lyophilized and purified according to the [12] SL-M2δ AChR purification procedure discussed above.

2.5 CD spectroscopy and MALDI-TOF

All of the synthesized and purified peptides were analyzed with CD spectroscopy and MALDI-TOF.

2.6 Sample preparation

The standard DMPC/DHPC bicelle samples, consisting of 25% (w/w) phospholipids to solution were made in 25 mL pear-shaped flasks. In one flask, DMPC, DHPC, PEG2000-PE, cholesterol and the spin-labels (CLS or n-DSA (n = 5, 7, 12, or 16)) were mixed together at molar ratios of 3.5/1/0.035/0.35/ 0.0196. However, the amounts of [1] SL-M2δ AChR or [12] SL-M2δ AChR spin-labels added to the bicelle samples were defined through double integration of the EPR spectra [21]. The chloroform in the flask was removed by nitrogen gas flow and then placed under high vacuum overnight. The following day, 100 mM HEPES buffer at pH 6.8 was added to the flask so the amount of lipids in the sample was 25% (wt%). The flask was then vortexed and put into an ice bath periodically until the sample became homogeneous and clear. The sample was sonicated for about 30 min with a FS30 (Fisher Scientific) ice bath sonicator with the heater turned off. The flask was left in an ice bath for approximately 10 min. Next, the sample was subjected to three to four freeze (77 K by liquid nitrogen) / thaw cycles (room temperature) to homogenize the sample and to remove any excess air bubbles. The total mass of the prepared samples was 200 mg.

In these EPR spectroscopic experiments, 4mM of ascorbic acid as a reducing agent was added to the bicelle sample that contains 2mM nitroxide spin-labels (CLS or n-DSA (n = 5, 7, 12, or 16)) incorporated into phospholipid bilayers. It has been found after analysis of a set of experiments of spin-labels incorporated into the bicelle that this oxidation-reduction reaction obeys a first order reaction when 4mM of ascorbic acid is added to the spin-labeled bicelle system. In the [1] SL-M2δ AChR or [12] SL-M2δ AChR bicelle samples, an appropriate amount of ascorbic acid is added to the sample after the amount of spin-label was determined by comparing double integrated EPR spectra with that of standard sample made of n-DSA.

2.7 EPR spectroscopy

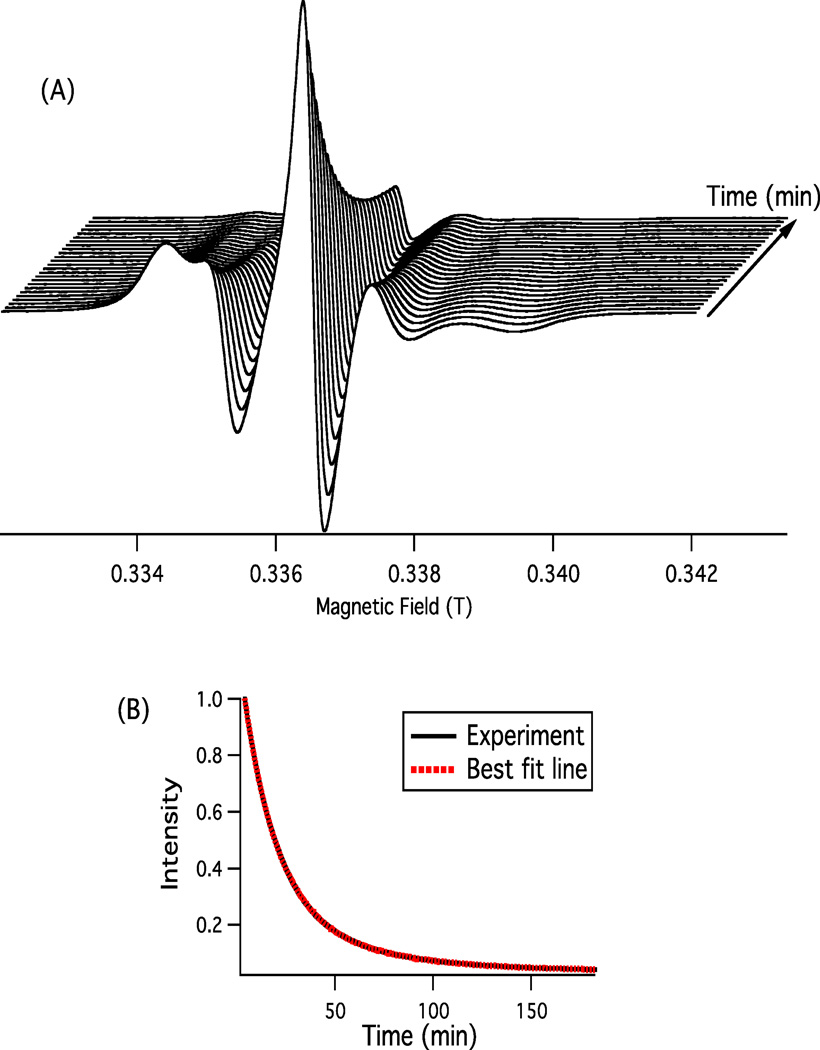

In the two-dimensional experiment shown in Figure 2(A), the EPR signal was recorded automatically every two minutes. Then, the signal amplitude of the center field hyperfine line (MI = 0) of each EPR spectrum was measured manually. Additionally, time-resolved EPR spectra were collected as shown in Figure 2(B), the decay curve experiments were performed by obtaining the time-dependent changes in the concentration of nitroxide or the decay of the EPR signal by setting the magnetic field at the top field position of the center field hyperfine line (MI = 0) of the EPR spectrum and then recording the rate of reduction in the time scan mode. The signal amplitude is recorded automatically every 2.62 sec. Each experiment lasted for 3 hrs.

Figure 2.

(A) Two-dimensional EPR spectra of 5-DSA spin-label incorporated into DMPC/DHPC phospholipid bilayers as a function of time after the addition of ascorbic acid in the gel-phase at 298 K. The spectra were recorded at 2 minutes regular intervals for 45 minutes. (B) EPR kinetic decay curves of the reduction of 5-DSA spin-label incorporated into a standard DMPC/DHPC bicelle system by ascorbic acid in the gel-phase at 298 K. The exponential data (black solid line) was fit via a single exponential equation.

The bicelle samples were placed into 1 mm ID capillary tubes (Kimax) via a syringe. Both ends of the capillary tubes were sealed with Critoseal (Fisher Scientific) and placed inside standard quartz EPR tubes (Wilmad, 707-SQ-250M) filled with light mineral oil. All EPR experiments were carried out on a Bruker EMX X-band CW-EPR spectrometer consisting of an ER041XG microwave bridge and a TE102 cavity coupled with a BVT 3000 nitrogen gas temperature controller (temperature stability of ± 0.2°C). All EPR spectra were gathered with a center field of 0.3350 T, sweep width of 100 G, a microwave frequency of 9.39 GHz, modulation frequency of 100 kHz, modulation amplitude of 1.0 G, and a power of 6.3 mW. All of the EPR spectra and resulting graphs were processed on an iMac G5 computer utilizing the Igor Carbon software package (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).

3. Results

Figure 2 shows the decrease in signal intensity of the EPR spectra of 5-DSA spin-label incorporated into DMPC/DHPC phospholipid bilayers as a function of time after the addition of ascorbic acid. The signal intensity is directly proportional to the concentration of the nitroxide spin-label. The full two-dimensional EPR spectra and the kinetic decay curve methods as described in the Materials and Methods section are represented in Figures 2(A) & 2(B), respectively. Both methods can be employed to probe the kinetics of the oxidation-reduction reaction. The full two-dimensional method takes longer and is less accurate since the signal amplitude of the center field hyperfine line (MI = 0) of each EPR spectrum is measured manually every 2 min. The decay curve method is easier, faster, and more accurate since the signal amplitude (MI = 0) is recorded automatically every 2.62 sec. Similar kinetic results have been obtained for both of these two methods when applied to the same set of samples. Therefore, the decay curve method has been applied for the rest of the experimental work for its simplicity and accuracy.

The black solid and red dotted decay curves observed in Figure 2(B) represent the experimental and best-fit reduction decay curves of the 5-DSA spin-label incorporated into the bicelle system, respectively. It is clearly noticeable that at 298 K (Figure 2(B)), the experimental data is perfectly fit by a single exponential function (red). The observed best-fit curve is shown here as an example of the precise fits achieved in all of the experimental data. Kinetic decay curves of the reduction of the nitroxide group incorporated into bicelles in the gel (298 K) and liquid-crystalline (318 K) phases have been easily fitted to the following single and double exponential functions, respectively:

- IEPR = If + A· e-kt

(1) (2)

Where IEPR is the EPR signal intensity at a position corresponding to the maximum of the center field peak of the EPR spectra, which is proportional to the paramagnetic nitroxide concentration in the bicelle sample. If is the maximum EPR signal intensity of the center field peak of the EPR spectrum when time (t) levels off. A, A1, and A2 are coefficients. k, k1, and k2 represent the corresponding reduction rate constants.

In the gel-phase (298 K), the spectra are easily fit with a single exponential decay curve. A double exponential fit is required to properly fit the data in the Lα-phase (318 K). The double exponential function indicates the occurrence of two different kinetic processes. The first rate constant is fast and characterized by the EPR signal disappearance as a result of the reduction reaction between the mono anionic form of ascorbic acid and the nitroxide group at physiological pH. Conversely, the second rate constant is much slower. The decay rate constant (k) is dependent on the depth of penetration of the paramagnetic nitroxide group into the bicelle system. The dynamic and permeability properties of the spin label in the Lα-phase are revealed by examining the first rate constants.

Two different issues could cause the double exponential fit obtained in the Lα-phase. First, an EPR and UV spectroscopic study has suggested that the occurrence of the second slower rate constant is related to the bulk pH and high initial concentration of ascorbic acid ([asc]/[SL] molar ratio of 1/7.5 or higher) [22]. The presence of the second phase at physiological or higher pH is ascribed to the formation of the dianionic form of ascorbic acid and/or regeneration of the fully protonated form of ascorbic acid [22]. This explains the presence of the two rate constants in our study where the bicelle samples in all of the experiments are prepared at physiological pH with [asc]/[SL] molar ratio of approximately 2/1. Second, the different exponential fits obtained for different bicelle phases propose that the decay kinetics are dependent upon the motion, dynamics, and temperature of the system. The kinetics of reactions in membranes is expected to show two phases if the nitroxide is located in two or more different regions [17]. Therefore, the biphasic kinetic in the liquid-crystalline phase is associated with the fast exchange of nitroxide under these conditions.

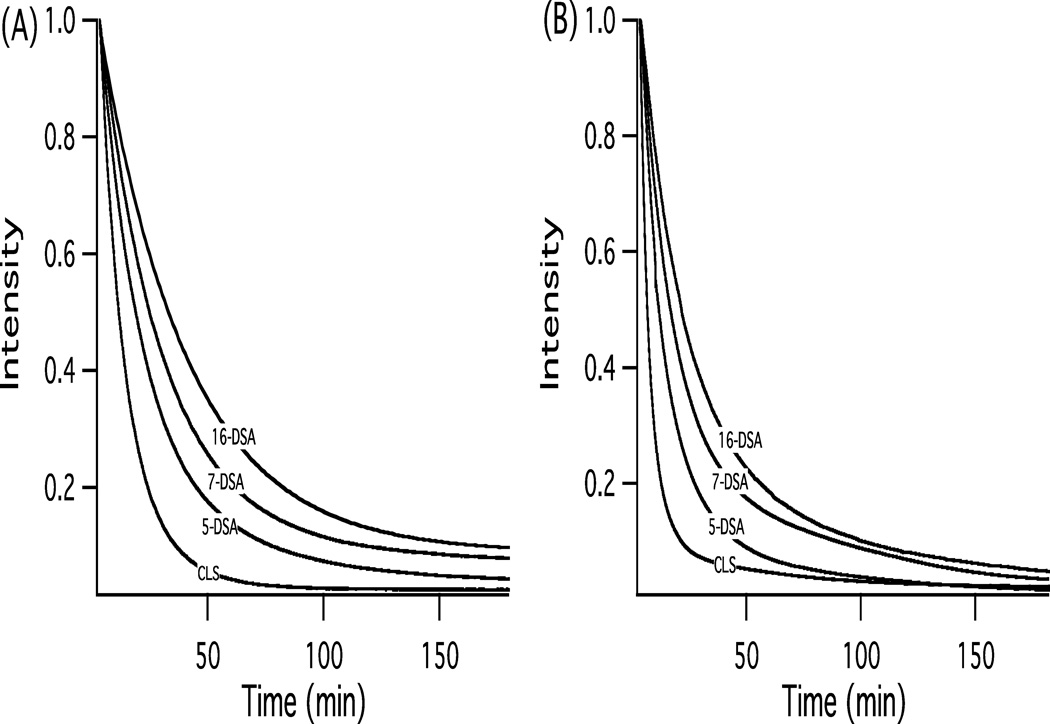

3.1 The effect of the depth of penetration of nitroxide spin-labels into bicelles

EPR kinetic decay curves profiling the reduction of 2mM nitroxide spin-labels (CLS, 5, 7, and 16-DSA) incorporated into DMPC/DHPC bicelle system by 4mM ascorbic acid in the gel-phase at 298 K and Lα-phase at 318 K is displayed in Figures 3(A) & 3(B), respectively. The EPR signal decay rate of paramagnetic nitroxides to their corresponding diamagnetic hydroxylamines is dependent on the depth at which the nitroxide group is located in the membrane. Table 1 displays the corresponding rate constants (k) of the decay curves shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

EPR kinetic decay curves of the reduction of 2mM nitroxide spin-labels (CLS and n-DSA; n = 5, 7, and 16) incorporated into DMPC/DHPC bicelle system by 4mM ascorbic acid in the (A) gel-phase at 298 K and (B) Lα-phase at 318 K. The kinetic data obtained in the gel-phase and Lα-phase was fit to single exponential and bi-exponential functions, respectively. Data points were collected on the center field hyperfine line (MI = 0) of the EPR spectra every 2.62 sec.

Table 1.

The reduction rate constants and the observed immersion depths of nitroxide spin-labels incorporated into the bicelle system are demonstrated in the gel-phase at 298 K and the Lα-phase at 318 K. The observed immersion depths of nitroxide spin-labeled peptides [1] SL-M2δ AChR and [12] SL-M2δ AChR are obtained from the graphs in Figures 4(A) & 4(B).

| Spin-Labels | Gel-phase (298 K) | Liquid-crystalline phase (318 K) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k (min−1) | Depth (Å) | k (min−1) | Depth (Å) | |

| CSL | 0.083 ± 0.008 | 6.0 ± 2.0 | 0.247 ± 0.004 | 6.0 ± 2.0 |

| 5-DSA | 0.043 ± 0.007 | 13.0 ± 2.0 | 0.111 ± 0.004 | 11.8 ± 2.0 |

| 7-DSA | 0.038 ± 0.002 | 15.0 ± 2.0 | 0.090 ± 0.007 | 13.3 ± 2.0 |

| 12-DSA | 0.030 ± 0.006 | 20.0 ± 2.0 | NA | 17.0 ± 2.0 |

| 16-DSA | 0.0265± 0.003 | 24.0 ± 2.0 | 0.057 ± 0.001 | 20.0 ± 2.0 |

| [1] SL-M2δ AChR | 0.086 ± 0.006 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 0.515 ± 0.070 | 3.0 ± 0.5 |

| [12] SL-M2δ AChR | 0.028 ± 0.001 | 21.7 ± 2.0 | 0.059 ± 0.004 | 19.0 ± 1.5 |

Small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) experiments of the structural phases of the bicelle system revealed that the phospholipid bilayer thickness and the hydrophobic thickness were estimated to be 50 ± 2 Å and 34 ± 2 Å in the gel-phase and 43 ± 2 Å and 27 ± 2 Å in the perforated lamellar phase (Lα-phase), respectively [13]. The phospholipid bilayer thickness increases by ~ 7 Å as the morphology of the bicelle transforms from the perforated lamellar phase to the gel phase [13]. The hydrophilic thickness of the bicelle system is 8 ± 2 Å [13]. The five C-C bonds are assumed for the 5-doxylsteric acid because the carbon from the carboxyl carbon is assumed to be the starting point of the lipid bilayer for this study. Thus the 5 C-C bonds in 5-DSA etc. are assumed to be the lipid depths. The data indicates that the immersion depth of C-C bond in the stearic acid hydrocarbon chain is ~ 1 Å and ~ 0.75 Å in the gel phase and the liquid crystalline phase, respectively. Accordingly, the immersion depth values of 5, 7, 12, and 16-DSA are calculated in Table 1 with an error of ± 2 Å along with the SANS study error.

The dynamic and permeability properties of the spin label in the bicelle system are revealed by examining the corresponding rate constants. The decay rate constant (k) is dependent on the depth of penetration of the paramagnetic nitroxide group into the bicelle system. Therefore, k decreases as the nitroxide group is located deeper within the lipid bilayer, (CLS, 5-DSA, 7-DSA, and 16-DSA), respectively. It is documented in the literature that ascorbic acid molecules permeate from the aqueous phase towards the membrane embedded spin-labels and the reduction rate of nitroxide spin-labels is dependent on the depth of penetration [16]. Dixon et al. have employed this method to confirm that the paramagnetic nitroxide group attached to the ATPase inhibitors is buried in the membrane [23]. Kostetski et al. have also utilized the reduction kinetics of nitroxides by ascorbic acid to illustrate the molecular interactions between pacitaxel, antineoplastic drugs, cholesterol, and lipid bilayer membranes [24]. Therefore, the bicelle results shown in Figure 3 and in Table 1 are in a good agreement with previous studies on different membrane systems and can be used as a complementary technique to quantitatively investigate the immersion depth of transmembrane peptides incorporated into the model bicelle system.

The reduction rate constants displayed in Table 1 indicate that the nitroxide spin-labels in DMPC/DHPC bicelles are reduced faster in the Lα-phase than in the gel-phase. Bicelles are in the form of bicelle discs or perforated lamellar sheets in the gel or Lα-phases, respectively [25, 26]. The reduction decay curves and rate constants reveal that the bicelle system in the Lα-phase possesses higher reducing ability than in the gel-phase. The gel phase is characterized by a rigid-like phase with a considerable hydrocarbon chain order and a phospholipid bilayer thickness of ~ 50 Å [26, 27]. However, the Lα-phase is characterized by a mobile-like phase with a considerable hydrocarbon chain disorder and a phospholipid bilayer thickness of ~ 43 Å [26, 27]. Therefore, the bicelle system in the Lα-phase has higher mobility that induces the accessibility of ascorbic acid into the phospholipid bilayers, in addition to that the bicelle system in the perforated lamellar sheets in the Lα-phase has a smaller phospholipid bilayer thickness (~ 7Å less) when compared to the bicelles in the gel-phase.

Previous biophysical studies have estimated the immersion depths of different spin-labeled phospholipids along the phospholipid bilayers as a control to evaluate the immersion depths of transmembrane proteins incorporated into membrane systems [2, 4, 5, 11, 16]. An EPR power saturation study revealed that the immersion depths of the spin probes of 5 and 7-doxyl-PCs, 1-palmitoyl-2-stearoyl-(n-doxyl)-PC (n = 5 and 7), in POPC/POPG phospholipid bilayers are 13.5 ± 2 Å and 16 ± 2 Å, respectively [11]. In addition, EPR spectroscopic methods have been utilized to study immersion depths based upon the dipolar interactions of the nitroxide with paramagnetic reagents, which is dominated by Mn2+ or other paramagnetic ions bound to the surface of phospholipid vesicles [5]. The estimated distances from the membrane surface in that study for 5, 7, 12, and 16-doxyl-PCs are 13.6, 15.2, 18.8, and 20.3 Å, respectively, with an error of ± 1.5 Å due to the uncertainty in the value taken for the spin-lattice relaxation time of the paramagnetic ion [5]. Additionally, fluorescence quenching experiments have shown that the 5 and 12 spin-labeled PCs distances from the spin-label to the hydrocarbon chain-head group interface are 2.85 ± 1.0 Å and 9.15 ± 1.0 Å, respectively [4]. The hydrophilic thickness is approximately 8 Å [26]. Therefore, the estimated distances from the membrane surface for 5 and 12-doxyl-PCs are 10.9 and 17.2 Å, respectively, with an error of ± 1.0 Å.

Small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) experiments of the structural phases of the bicelle system revealed that the phospholipid bilayer thickness and the hydrophobic thickness were estimated to be 50 ± 2 Å and 34 ± 2 Å in the gel-phase and 43 ± 2 Å and 27 ± 2 Å in the perforated lamellar phase (Lα-phase), respectively [26]. The phospholipid bilayer thickness increases by ~ 7 Å as the morphology of the bicelle transforms from the perforated lamellar phase to the gel phase [26]. The hydrophilic thickness of the bicelle system is 8 ± 2 Å [26]. The five C-C bonds are assumed for the 5-doxylsteric acid because the carbon from the carboxyl carbon is assumed to be the starting point of the lipid bilayer for this study. Thus the 5 C-C bonds in 5-DSA etc. are assumed to be the lipid depths. The data indicates that the immersion depth of C-C bond in the stearic acid hydrocarbon chain is ~ 1 Å and ~ 0.75 Å in the gel phase and the liquid crystalline phase, respectively. Accordingly, the immersion depth values of 5, 7, 12, and 16-DSA are calculated in Table 1 with an error of ± 2 Å along with the SANS study error.

As discussed previously, the calculated depth values of 5, 7, 12, and 16-DSA spin-labels used in this study (Table 1) are consistent with various studies that have estimated the immersion depths of different spin-labeled phospholipids along various membrane systems within the experimental errors [4, 5, 11]. Different bicelle system morphologies, that are highly dependent on temperature and gel or Lα-phases, can affect the dynamics and permeability properties of the phospholipid bilayers and as a result will influence the membrane-bound peptides immersion depth assessment. Consequently, the calculated depth values of spin-labels obtained through the SANS study on bicelles are more favorable for comparison to be used in this study.

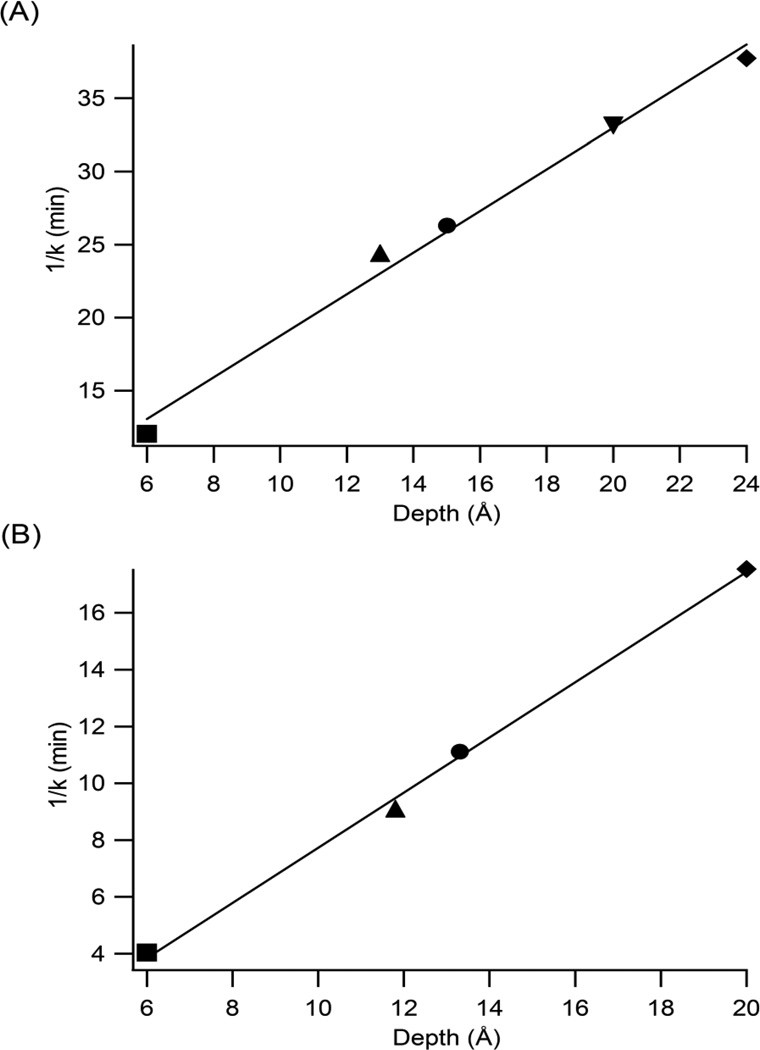

3.2 Immersion depth studies of bicelle-bound spin-labeled M2δ AChR

The purpose of this study is to develop a methodology to determine the immersion depth of site-specific spin-labeled residues of membrane-bound peptides or proteins based on the kinetic analysis of the reaction of the ascorbic acid molecule with the paramagnetic nitroxide group of the different spin probes incorporated into the bicelles by EPR spectroscopy. The decay rate constant is inversely dependent upon the depth of the spin-label in the membrane [16]. Therefore, the inverse rate constants are plotted as a function of the observed depths for the nitroxide spin-labels (CLS and n-DSA, n = 5, 7, 12, and 16) incorporated into bicelle samples in the gel-phase (298 K) and Lα-phase (318 K) in Figures 4(A) & 4(B), respectively. The depth can be determined directly from the slope by plotting the kinetic rate vs. inverse depth (plot not shown). The rate constant values and the observed depth values were obtained from the fits as displayed in Table 1. These graphs represent calibration curves to determine the depth of immersion of spin-labeled peptides in the gel and Lα-phases. Inspection of Figure 4 clearly indicates that the plots are linear and that the inverse constant k is directly proportional to the depth.

Figure 4.

EPR rate constant are plotted as a function of depth of the nitroxide spin-labels (■, CLS), (▲, 5-DSA), (●, 7-DSA), (◄, 12-DSA), and (◆, 16-DSA) incorporated into bicelle system in (A) the gelphase at 298 K and (B) the Lα-phase at 318 K. The observed immersion depths for the nitroxide spinlabels are demonstrated in Table 1. The linear regression lines (□) represent the best-fit line in the graphs.

The depth of CLS (6 Å) was obtained by extrapolation of the best-fit profile obtained with n-DSA spin-labels in Figures 4(A) & 4(B). It is assumed that the hydrophilic thickness does not change at different temperatures and bicelle morphologies [26]. This fact explains the similarity in the depths of nitroxide groups of the CLS spin-labels in the gel-phase (298 K) and Lα-phase (318 K) in the bicelle system. Schreier-Muccillo et al. have followed the same procedure in determining the CLS spin-label depth [16]. Molecular dynamic simulations have indicated that the cholesterol hydroxyl group is located in the polar head group-hydrocarbon chain interface in the phospholipid bilayers and experiences hydrogen bonding with the PC oxygen atoms which makes this hydroxyl group located in the bottom part of the polar head group region [28]. Another molecular dynamics study has shown that the cholesterol hydroxyl group is equally split between the phosphate and carbonyl groups of phospholipid head groups. The cholesterol ring system is situated such that C3 (to which the hydroxyl is attached) is at the same distance from the bilayer surface (5 Å) as C2 in the DPPC acyl chains [29]. The CLS spin-label is a cholesterol-like structure except that the nitroxide group on the CLS spin-label replaces the hydroxyl group in cholesterol as shown in Figure 1. It is proposed in the literature that the CLS spin-label possesses a similar location as cholesterol in the phospholipid bilayers. Then, the nitroxide group of CLS spin-label will presumably be located in the bottom part of the polar head group region. Therefore, a 6 Å depth value obtained for the nitroxide group of CLS spin-label through extrapolation of the best-fit lines in Figures 4(A) & 4(B) agrees well with the assumption driven through the molecular simulation results.

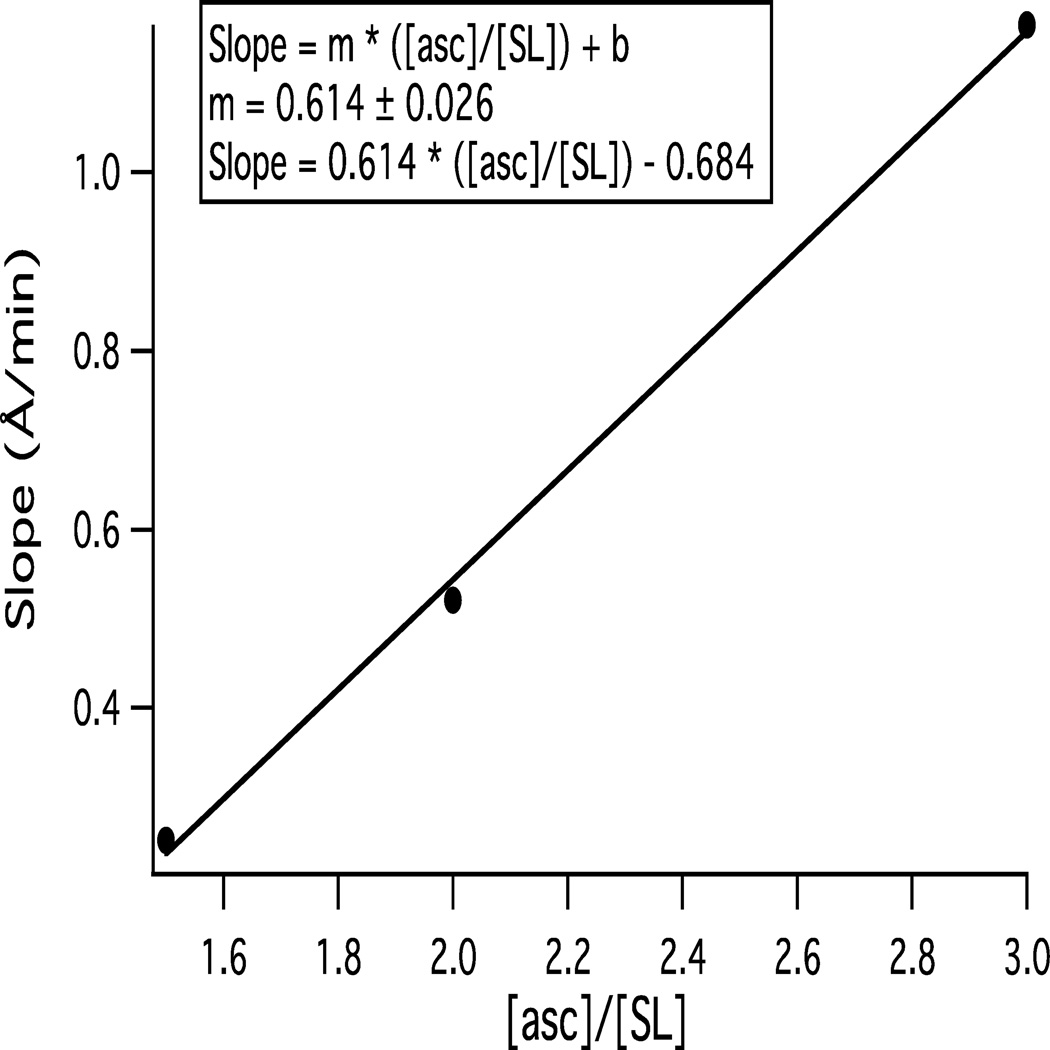

The EPR decay curves and the corresponding rate constants displayed in Figure 3 and Table 1 are directly dependent upon the relative concentration of ascorbate and the spin-label ([asc]/[SL]). Thus, the slopes depend upon the corresponding [asc]/[SL] ratio. The reduction rate constants (k) of the different spin-labels (CLS and n-DSA, n = 5, 7, 12, and 16) have been determined as a function of inverse depth (1/Depth) for different [asc]/[SL] ratios (data not shown). Subsequently, the observed slopes are plotted as a function of [asc]/[SL] in Figure 5. The data fit in Figure 5 is linear according to the following equation:

| (3) |

where the slope (Å/min) is the y-axis (obtained through k vs. 1/Depth for different [asc]/[SL] ratios), m is the slope of the function (slope vs. [asc]/[SL]), [asc]/[SL] is the x-axis, and b is the intercept. Figure 5 fits to the following expression:

| (4) |

where m = 0.614 ± 0.026. Therefore, the slope obtained is dependent upon the [asc]/[SL] molar ratio and varies according to equation (4). This equation can be used to calculate the slope for only the range of [asc]/[SL] ratio shown in this paper (1.5:1, 2:1, and 3:1). This equation can be applied to a protein of interest with a known spin label concentration. The protein spin label concentration can be easily determined through spin quantitation on the CW-EPR spectrometer. The applicability of this method over a wider [asc]/[SL] ratio range and whether it is pertinent to other phospholipid bilayer systems will be explored in future work. Equation (4) provides a means for determining the immersion depth of spin-labeled transmembrane peptides within a range of [asc]/[SL] molar ratios.

Figure 5.

The slope (Å/min) is plotted as a function of [asc]/[SL] molar ratios. The slope values are obtained from plotting the reduction rate constants of CLS and n-DSA (n = 5, 7, 12, and 16) spin-labels as a function of inverse depths in the gel-phase. The linear line (□) represents the best-fit line in the graph.

Similar time-resolved EPR kinetic data was collected for the reaction of the ascorbic acid molecule with the paramagnetic nitroxide group of the spin-labeled [1] SL-M2δ AChR and [12] SL-M2δ AChR transmembrane peptides incorporated into bicelles to determine their corresponding rate constants (data not shown). The corresponding [1] SL-M2δ AChR and [12] SL-M2δ AChR transmembrane peptides reduction rate constants are displayed in Table 1. Figures 4(A) & 4(B) have been used to determine the inverse depth of [1] SL-M2δ AChR and [12] SL-M2δ AChR transmembrane peptides; thus, their depth of immersion into the bicelles. Based upon the data in Figures 4 and 5, the calculated immersion depths of Glu-1 of spin-labeled M2δ AChR peptide was 5.8 Å and 3 Å in the gel-phase (298 K) and Lα-phase (318 K), respectively. Similarly, the spin-labeled M2δ AChR peptide at Ala-12 is buried at 21.7 Å and 19 Å in the gel and Lα-phases, respectively.

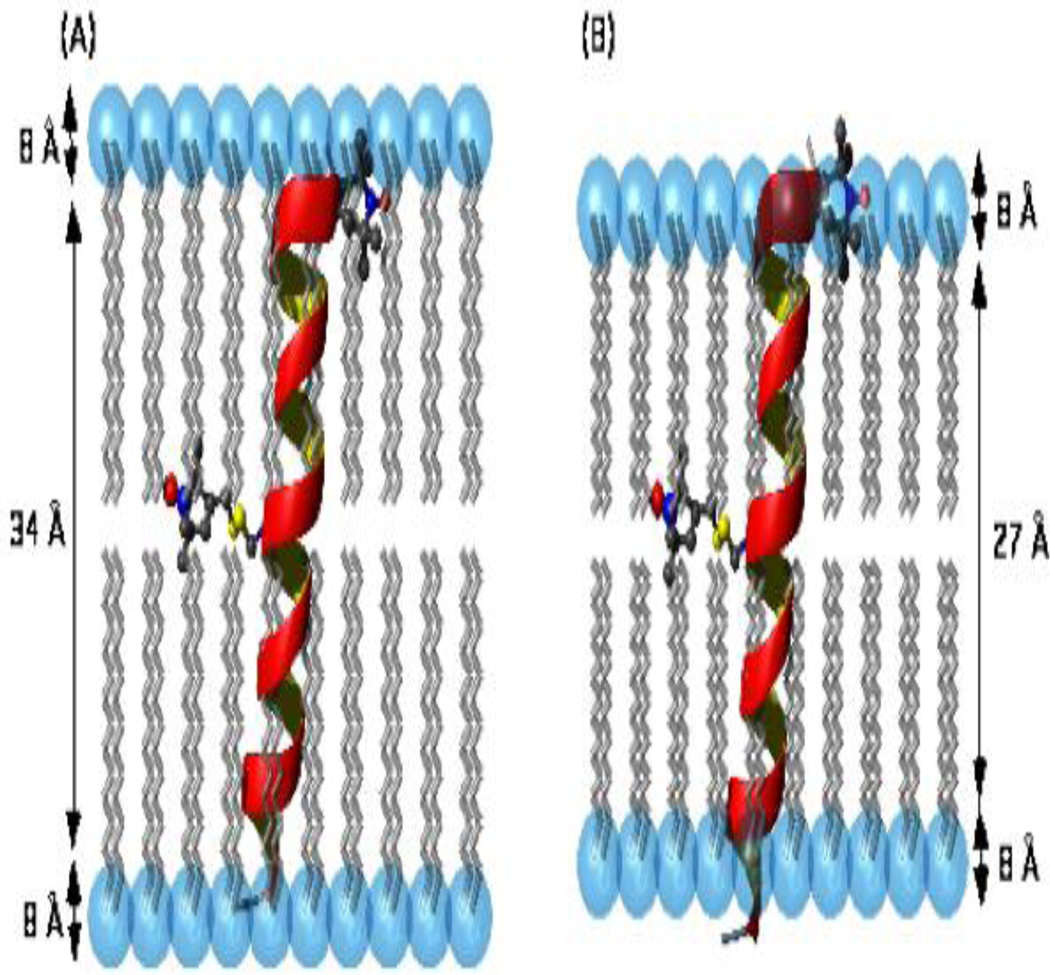

The structural models displayed in Figure 6 indicate the locations of the nitroxide (NO•) spin-labels attached to site-specific (Glu-1 and Ala-12) spin-labeled M2δ AChR peptides incorporated into DMPC/DHPC bicelle system in the gel and Lα-phases. As shown in Figure 6(A), the (NO•) spin-label attached to Glu-1 of the M2δ AChR peptide with an immersion depth of 5.8 Å is located in the hydrophilic-hydrophobic interface region in the gel-phase. However, the (NO•) spin-label attached to [1] SL-M2δ AChR peptide with an immersion depth of (3.0 Å) is located in the middle of the hydrophilic head group region in the Lα-phase as illustrated in Figure 6(B). Conversely, the (NO•) spin-label attached to Ala-12 of the M2δ AChR peptide is located in the interior of the hydrophobic region of the membrane in the gel and Lα-phases as illustrated in Figures 6(C) & 6(D), respectively. The [12] SLM2 δ AChR peptide is buried at the same position in the bicelle system regardless of the bicelle phases (gel or Lα-phases). The different immersion depths (21.7 Å in the gel-phase and 19.0 Å in the Lα-phase) are attributed to the different phospholipid bilayer thicknesses in the two different bicelle phases.

Figure 6.

Structural models of [1] SL-M2δ AChR peptides in the (A) gel-phase and (B) Lα-phase and [12] SL-M2δ AChR peptides in the (C) gel-phase and (D) Lα-phase incorporated into DMPC/DHPC bicelle system. The locations of the nitroxide (NO•) attached to site-specific spin-labeled peptides are represented in blue and red balls. The phospholipid bilayer thicknesses are 50 Å and 43 Å, the hydrophobic thicknesses are 34 Å and 27 Å, and the polar head group thickness is 8 Å, respectively, in the gel and Lα-phases with an error of ± 2 Å.

Assuming that the number of amino acids per turn in an α-helix peptide is 3.6 residues and the pitch is 5.4 Å, then the translation per residue along the α–helical peptide will be 1.5 Å. Thus, the length of the M2δ AChR peptide segment containing 23 amino acid residues and inserted into the bicelle system at an angle of 12°, with respect to the bilayer normal, is ~ 34 Å [12]. According to the phospholipid bilayer, hydrophobic, and hydrophilic thickness values of the bicelle system mentioned earlier in this report, the theoretical immersion depth values of Glu-1 should be 8.0 ± 2.0 Å and 4.5 ± 2.0 Å and 25.0 ± 2.0 Å and 21.5 ± 2.0 Å for Ala-12 for the M2δ AChR peptide incorporated into DMPC/DHPC bicelles in the gel and Lα-phases, respectively. The immersion depth results obtained in this kinetic EPR study are consistent with the results reached from the theoretical pitch calculations.

It is apparent that the theoretical pitch immersion depth values for Glu-1 and Ala-12 of M2δ AChR peptide are approximately 2–3 Å higher when compared to the observed immersion depth values obtained through this EPR kinetic study in the gel and Lα-phases. In the continuum-solvent model study, the free energy of association of M2δ AChR with lipid bilayers with different widths has been calculated [30].

4. Discussion

The results have suggested a reduction in the phospholipid bilayer thickness in response to peptide insertion to stabilize the interactions between the polar terminus of the peptide and the polar lipid head groups as illustrated by Monte Carlo simulations [30]. In addition, the stability of the amphiphilic M2δ AChR peptide can be achieved when its hydrophobic core interacts with the hydrocarbon region of the phopholipid bilayer and its hydrophilic terminal amino acid residues interact with the polar head group region of the phospholipid bilayer. Therefore, molecular dynamic simulations of the M2δ AChR peptide inserted into phospholipid bilayers suggest that the apparent mismatch between the helix length and phospholipid bilayer thickness is compensated by the C-terminal arginine side chain which reaches up to form hydrogen bonds with the polar head group atoms of the phospholipid molecules [31]. Therefore, the small difference between the observed and theoretical immersion depth values can be accounted for by the reduction in phospholipid bilayer thickness induced by the incorporation of M2δ AChR peptide into the phospholipid bilayers, as well as, a compensation for the mismatch between the helix length and the phospholipid bilayer thickness.

Interestingly, amphiphilic peptides like M2δ AChR may adsorb onto the bilayer surface or insert into the bilayer and assume a transmembrane orientation [12, 30]. The immersion depth values of spin-labeled [12] SL-M2δ AChR peptide attained in this kinetics study are 21.7 Å and 19.0 Å in the gel and Lα-phases, respectively. These results imply that the peptide segment is inserted into the bicelle and does not lay on the surface of the membrane. Therefore, the transmembrane orientation is the most favorable orientation of the peptide in the phospholipid bilayer. The proposed structural model of the bicelle-bound M2δ AChR peptide agrees well with structural models of the M2δ AChR peptide segment inserted into lipid bilayers obtained utilizing solid-state NMR spectroscopy, continuum-solvent model calculations, Monte Carlo simulations, and molecular dynamics simulations studies [12, 30–33]. Therefore, this new kinetic technique using bicelles can be successfully employed to estimate the immersion depth of site-specific spin-labeled residues of membrane-bound peptides utilizing EPR spectroscopy.

The presence of transmembrane proteins can change the membrane permeability of the lipid environment and thus may need to be investigated for each system individually. The M2δ AChR peptide represents a proof of concept. This system has been studied extensively by various spectroscopic techniques: flourescence, NMR, and pulsed EPR to address this issue specifically. In the current work, small changes in concentration of labeled or non-labeled peptide did not affect the distance measurements. Future work will explore using MTSL labeled peptides at various sites titrated with unlabeled protein, which would give us a more accurate ruler in this membrane system.

It should be noted that while our technique can be successfully employed our experimental times are lengthened because the spin label is prone to reduction. Additionally the degree of penetration of the ascorbate into the bilayer is also known to change depending on the lipid architecture and membrane phase state. Finally, ascorbic acid may have a difficult time interacting with some spin-labeled residues that are buried in a cluster or one that forms an oligomer.

In the current study, the structural characteristics and behaviors of the M2δ AChR peptide have been explored to assist in investigating the biological implications and function of the entire acetylcholine receptor. In addition, the M2δ AChR segment has been used as a model for membrane-bound peptides and proteins to test the validity of the discussed kinetic technique in estimating the immersion depth of site-specific membrane-bound peptides utilizing EPR spectroscopy. The excellent exponential fits attained in the reduction decay curves reveal the high precision in rate constants; thus, revealing the corresponding immersion depth values. This novel technique should be applicable to a wide range of integral membrane proteins via EPR spectroscopy. These membrane depth EPR kinetic measurements utilize a standard CW-EPR resonator and not a specialized loop gap resonator for power saturation measurements.

Highlights.

-

>

EPR spectroscopic methods developed for measuring membrane depth

-

>

Kinetic decay curves reveal membrane depth

-

>

Bicelles are an excellent model membrane system

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the following grants NIH-GM60259-01, NSF-CHE-0645709, and MRI- 0722403.

Abbreviations

- Lα-phase

liquid-crystalline phase

- M2δ

M2 segment of the δ subunit

- AChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- EPR spectroscopy

electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

- CLS

cholestane (3β-doxyl-5α-cholestane)

- n-DSA (n = 5, 7, 12, and 16)

5, 7, 12, and 16-doxylstearic acids

- DMPC

1, 2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine

- DHPC

1, 2-Dihexanoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine

- Δχ

magnetic susceptibility anisotropy tensor

- [1]

amino acid residue 1

- [12]

amino acid residue 12

- SL

spin-labeled

- [1] SL-M2δ AChR

M2δ AChR peptide subunit spin-labeled at amino acid residue 1

- [12] SL-M2δ AChR

M2δ AChR peptide subunit spin-labeled at amino acid residue 12

- NMR spectroscopy

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- MTSSL

1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-Δ3-pyrroline-3-methyl-methanethiosulfonate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Altenbach C, Greenhalgh DA, Khorana HG, Hubbell WL. A collision gradient method to determine the immersion depth of nitroxides in lipid bilayers: application to spin-labeled mutants of bacteriorhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:1667–1671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams FS, Chattopadhyay A, London E. Determination of the location of fluorescent probes attached to fatty acids using parallax analysis of fluorescence quenching: effect of carboxyl ionization state and environment on depth. Biochem. 1992;31:5322–5327. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buffy JJ, Hong T, Yamaguchi S, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI, Hong M. Solid-state NMR investigation of the depth of insertion of protegrin-1 in lipid bilayers using paramagnetic Mn2+ Biophys. J. 2003;85:2363–2373. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chattopadhyay A, London E. Parallax method for direct measurement of membrane penetration depth utilizing fluorescence quenching by spin-labeled phospholipids. Biochem. 1987;26:39–45. doi: 10.1021/bi00375a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalton LA, McIntyre JO, Fleischer S. Distance estimate of the active center of D-β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase from the membrane surface. Biochem. 1987;26:2117–2130. doi: 10.1021/bi00382a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frazier AA, Wisner MA, Malmberg NJ, Victor KG, Fanucci GE, Nalefski EA, Falke JJ, Cafiso DS. Membrane orientation and position of the C2 domain from cPLA2 by site-directed spin labeling. Biochem. 2002;41:6282–6292. doi: 10.1021/bi0160821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenhalgh DA, Altenbach C, Hubbell WL, Khorana HG. Locations of Arg-82, Asp-85, and Asp-96 in helix C of bacteriorhodopsin relative to the aqueous boundaries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:8626–8630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macosko JC, Kim C-H, Shin Y-K. The membrane topology of the fusion peptide region of influenza hemagglutinin determined by spin-labeling EPR. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:1139–1148. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prosser RS, Luchette PA, Westerman PW, Rozek A, Hancock REW. Determination of membrane immersion depth with O2: a high-pressure 19F NMR study. Biophys. J. 2001;80:1406–1416. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76113-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong AP, Groves JT. Molecular topography imaging by intermembrane fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14147–14152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212392599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu YG, Thorgeir TE, Shin YK. Topology of an amphiphilic mitochondrial signal sequence in the membrane-inserted state: a spin labeling study. Biochem. 1994;33:14221–14226. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opella SJ, Marassi FM, Gesell JJ, Valente AP, Kim Y, Oblatt-Montal M, Montal M. Structures of the M2 channel-lining segments from nicotinic acetylcholine and NMDA receptors by NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:374–379. doi: 10.1038/7610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson GG, Karlin A. Acetylcholine receptor channel structure in the resting, open, and desenitized states probed with the substituted-cysteine-accessibility method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:1241–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031567798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyazawa A, Fujiyoshi Y, Unwin N. Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature. 2003;423:949–955. doi: 10.1038/nature01748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fung LWM, Zhang Y. A method to evaluate the antioxidant system for radicals in erythrocyte membranes. Free Rad. Biol. 1990;9:289–298. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schreier-Muccillo S, Marsh D, Smith ICP. Monitoring the permeability profile of lipid membranes with spin probes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1976;172:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swartz NKaHM. Nitroxide Spin Labels: Reactions in Biology and Chemistry. 1 ed. CRC Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiburu EK, Dave PC, Vanlerberghe JF, Cardon TB, Minto RE, Lorigan GA. An improved synthetic and purification procedure for the hydrophobic segment of the transmembrane peptide phospholamban. Anal. Biochem. 2003;318:146–151. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marchetto R, Schreier S, Nakaie CR. A novel spin-labeled amino acid derivative for use in peptide synthesis: (9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl)-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl-4-amino-4-carboxylic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:11042–11043. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Victor KG, Cafiso DS. Location and dynamics of basic peptides at the membrane interface: electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy of tetramethyl-piperidine-N-oxyl-4-amino-4-carboxylic acid-labeled peptides. Biophys. J. 2001;81:2241–2250. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75871-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kocherginsky NM, Kostetski YY, Smirnov AI. Use of nitroxide spin probes and electron paramagnetic resonance for assessing reducing power of beer. Role of SH groups. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:1052–1057. doi: 10.1021/jf034787z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colacicchi S, Carnicelli V, Gualtieri G, Di Giulio A. EPR study of fremy's salt nitroxide reduction by ascorbic acid; influence of the bulk pH values. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2000;26:885–896. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixon N, Pali T, Kee TP, Marsh D. Spin-labelled vacuolar-ATPase inhibitors in lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1665:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tonomura Y, Morales MF. CHANGE IN STATE OF SPIN LABELS BOUND TO SARCOPLASMIC-RETICULUM WITH CHANGE IN ENZYMIC STATE, AS DEDUCED FROM ASCORBATE-QUENCHING STUDIES. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1974;71:3687–3691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.9.3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardon TB, Dave PC, Lorigan GA. Magnetically aligned phospholipid bilayers with large q ratios stabilize magnetic alignment with high order in the gel and Lα phases. Langmuir. 2005;21:4291–4298. doi: 10.1021/la0473005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nieh MP, Glinka CJ, Krueger S, Prosser RS, Katsaras J. SANS study of the structural phases of magnetically alignable lanthanide-doped phospholipid mixtures. Langmuir. 2001;17:2629–2638. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis JH. Deuterium magnetic resonance study of the gel and liquid crystalline phases of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine. Biophys. J. 1979;27:339–358. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85222-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M, Rog T, Kitamura K, Kusumi A. Cholesterol effects on the phosphatidylcholine bilayer polar region: a molecular simulation study. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1376–1389. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76691-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu K, Klein ML, Tobias DJ. Constant-pressure molecular dynamics investigation of cholesterol effects in a dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer. Biophys. J. 1998;75:2147–2156. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77657-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessel A, Haliloglu T, Ben-Tal N. Interactions of the M2δ segment of the acetylcholine receptor with lipid bilayers: a continuum-solvent model study. Biophys. J. 2003;85:3687–3695. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74785-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Law RJ, Forrest LR, Ranatunga KM, Rocca PL, Tieleman DP, Sansom MSP. Structure and dynamics of the pore-lining helix of the nicotinic receptor: MD simulations in water, lipid bilayers, and transbilayer bundles. Proteins. 2000;39:47–55. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(20000401)39:1<47::aid-prot5>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montal M, Opella SJ. The structure of the M2 channel-lining segment from the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1565:287–293. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saiz L, Klein ML. The transmembrane domain of the acetylcholine receptor: insights from simulations on synthetic peptide model. Biophys. J. 2005;88:959–970. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]