Abstract

Capacitance is a fundamental neuronal property. One common way to measure capacitance is to deliver a small voltage-clamp step that is long enough for the clamp current to come to steady state, and then to divide the integrated transient charge by the voltage-clamp step size. In an isopotential neuron, this method is known to measure the total cell capacitance. However, in a cell that is not isopotential, this measures only a fraction of the total capacitance. This has generally been thought of as measuring the capacitance of the “well-clamped” part of the membrane, but the exact meaning of this has been unclear. Here, we show that the capacitance measured in this way is a weighted sum of the total capacitance, where the weight for a given small patch of membrane is determined by the voltage deflection at that patch, as a fraction of the voltage-clamp step size. This quantifies precisely what it means to measure the capacitance of the “well-clamped” part of the neuron. Furthermore, it reveals that the voltage-clamp step method measures a well-defined quantity, one that may be more useful than the total cell capacitance for normalizing conductances measured in voltage-clamp in nonisopotential cells.

Keywords: Capacitance, Neurons, Voltage clamp

Introduction

Capacitance is a fundamental neuronal property. In an isopotential neuron, the capacitance times the input resistance yields the cell’s time constant, which determines how quickly the neuron’s membrane potential responds to inputs (Rall 1957). In nonisopotential cells, the specific capacitance and the specific membrane resistance play similar roles in determining the time constant at which the cell as a whole (i.e. averaged over space) responds to inputs (Rall 1969). Additionally, a measurement of capacitance is often useful as a stand-in for a measurement of cell surface area, because the capacitance scales with the surface area (Koch 1999, p. 8). Thus measurements of cellular capacitance have been used to normalize for variability in cell size, both in isopotential (Turrigiano et al. 1995; Swensen and Bean 2005) and nonisopotential neurons (Schulz et al. 2006; Khorkova and Golowasch 2007).

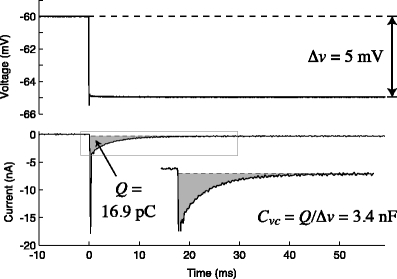

Several methods are in widespread use for measuring cell capacitance. One common method is to voltage clamp the cell near its resting membrane potential, and to deliver a small (generally ≤10 mV) voltage-clamp step, long enough for the resulting current to come to steady state. One then subtracts off the steady-state current to determine the transient current, and this is then integrated to calculate the transient charge delivered during the voltage-clamp step. The transient charge is then divided by the size of the voltage-clamp step to yield an estimate of the cell capacitance (Hodgkin et al. 1952; Golowasch et al. 2009, see also Gillis 2009, p. 160). I will call this the voltage-clamp step estimate of capacitance, or  (Fig. 1).

(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of  measurement, using data from the LP neuron of the crab Cancer borealis, measured using two-electrode voltage clamp. A small voltage-clamp step is delivered, of size Δv (top panel). The clamp current required to bring this about is measured (bottom panel). The steady-state current is subtracted off (dashed line). The area under the transient current is then calculated (shaded area, denoted Q). The voltage-clamp capacitance is then given by

measurement, using data from the LP neuron of the crab Cancer borealis, measured using two-electrode voltage clamp. A small voltage-clamp step is delivered, of size Δv (top panel). The clamp current required to bring this about is measured (bottom panel). The steady-state current is subtracted off (dashed line). The area under the transient current is then calculated (shaded area, denoted Q). The voltage-clamp capacitance is then given by

For an isopotential cell, the voltage-clamp step method yields an accurate estimate of the total cell capacitance. But for nonisopotential cells, it has not been clear exactly how  relates to the total capacitance. It has generally been considered to be a measurement of the capacitance of the part of the cell that is “well-clamped”, but this is vague. In previous work, I and my coauthors found (although it is a rather trivial result) that in a two-compartment model,

relates to the total capacitance. It has generally been considered to be a measurement of the capacitance of the part of the cell that is “well-clamped”, but this is vague. In previous work, I and my coauthors found (although it is a rather trivial result) that in a two-compartment model,  is equal to a weighted sum of the capacitance of the two compartments, where the weights are determined by the size of the steady-state voltage deflection in each compartment, measured as a fraction of the voltage-clamp command step (Golowasch et al. 2009). Here I generalize this result, showing that for a neuron with arbitrary geometry,

is equal to a weighted sum of the capacitance of the two compartments, where the weights are determined by the size of the steady-state voltage deflection in each compartment, measured as a fraction of the voltage-clamp command step (Golowasch et al. 2009). Here I generalize this result, showing that for a neuron with arbitrary geometry,  is equal to a weighted sum of the total cell capacitance, where the weights are determined by the size of the steady-state voltage deflection at each part of the neuron’s surface area, measured as a fraction of the voltage-clamp command step. This makes precise the idea that this method measures the “well-clamped” part of the capacitance.

is equal to a weighted sum of the total cell capacitance, where the weights are determined by the size of the steady-state voltage deflection at each part of the neuron’s surface area, measured as a fraction of the voltage-clamp command step. This makes precise the idea that this method measures the “well-clamped” part of the capacitance.

Results

I assume that the neuron being measured is effectively passive over the range of voltages used (see Section 3), and that it is a tree of cylinders, with each cylinder described by its capacitance per unit length, c m; its membrane resistance for a unit length, r m; its axial resistance per unit length, r a; and its length, l. These parameters are assumed to be uniform in each cylinder, but may vary across cylinders. I also assume that the cylinder tree has a uniform resting membrane potential, which can be assumed to be zero without loss of generality.

The voltage-clamp step capacitance is measured by voltage clamping the cell at some convenient location (normally the soma) and delivering a step:

|

1 |

where u(t) is the unit step function. The voltage-clamp step capacitance is then defined by

|

2 |

where i(t) is the clamp current delivered as a function of time (Fig. 1). The integral above yields the charge delivered by the transient part of the current, which is then divided by the size of the voltage step to yield  . It should be noted that computing this quantity does not require the “peeling” of exponentials (Rall 1969; Holmes et al. 1992).

. It should be noted that computing this quantity does not require the “peeling” of exponentials (Rall 1969; Holmes et al. 1992).

I now define a quantity which I call the “clamp-weighted capacitance”. The main result of this paper will be to show that the voltage-clamp step capacitance is equal to the clamp-weighted capacitance for any neuronal geometry. When the voltage-clamp step has been on long enough for the voltage at all points in the tree to come to steady-state, each point will have a voltage, denoted  , where k indexes the cylinders, and x represents the distance along a cylinder. The clamp-weighted capacitance is defined as

, where k indexes the cylinders, and x represents the distance along a cylinder. The clamp-weighted capacitance is defined as

|

3 |

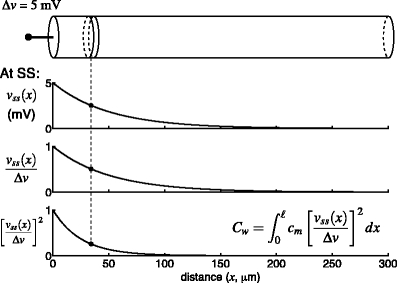

where  is the capacitance per unit length for the kth cable segment. That is, the clamp-weighted capacitance is calculated by dividing the cell surface area up into many small patches, and then adding up the capacitance of all these small patches, but with each patch weighted by a factor reflecting how much the voltage is deflected at that point (Fig. 2). In particular, this factor is equal to the square of the voltage deflection at each point, measured as a fraction of the voltage-clamp step size,

is the capacitance per unit length for the kth cable segment. That is, the clamp-weighted capacitance is calculated by dividing the cell surface area up into many small patches, and then adding up the capacitance of all these small patches, but with each patch weighted by a factor reflecting how much the voltage is deflected at that point (Fig. 2). In particular, this factor is equal to the square of the voltage deflection at each point, measured as a fraction of the voltage-clamp step size,  . The square was introduced because in the two-compartment case, a square factor arises in the expression for

. The square was introduced because in the two-compartment case, a square factor arises in the expression for  in terms of the two compartmental capacitances (Golowasch et al. 2009). And it turns out that

in terms of the two compartmental capacitances (Golowasch et al. 2009). And it turns out that  defined in this way can be proven equal to

defined in this way can be proven equal to  for an arbitrary geometry.

for an arbitrary geometry.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the clamp-weighted capacitance,  , in a single finite cable. The cable is voltage-clamped at the left end (top panel). Once the voltage-clamp has come to steady state (bottom three panels), the voltage in the cable is described by a hyperbolic cosine function (Eq. (15)). The fraction of the voltage-clamp step “felt” at any point in the cable is given by the fraction

, in a single finite cable. The cable is voltage-clamped at the left end (top panel). Once the voltage-clamp has come to steady state (bottom three panels), the voltage in the cable is described by a hyperbolic cosine function (Eq. (15)). The fraction of the voltage-clamp step “felt” at any point in the cable is given by the fraction  (third panel). The weight used in the calculation of

(third panel). The weight used in the calculation of  is given by the square of this fraction (bottom panel).

is given by the square of this fraction (bottom panel).  is calculated by dividing the surface area of the membrane into many slices (shown in top panel), each of which has a capacitance and a weight associated with it (dashed line).

is calculated by dividing the surface area of the membrane into many slices (shown in top panel), each of which has a capacitance and a weight associated with it (dashed line).  is given by the weighted sum of the capacitance of all of these slices. Because the weight varies continuously, this sum is given by an integral (inset)

is given by the weighted sum of the capacitance of all of these slices. Because the weight varies continuously, this sum is given by an integral (inset)

The main result of this paper is that  for any cable tree.

for any cable tree.

Proof that

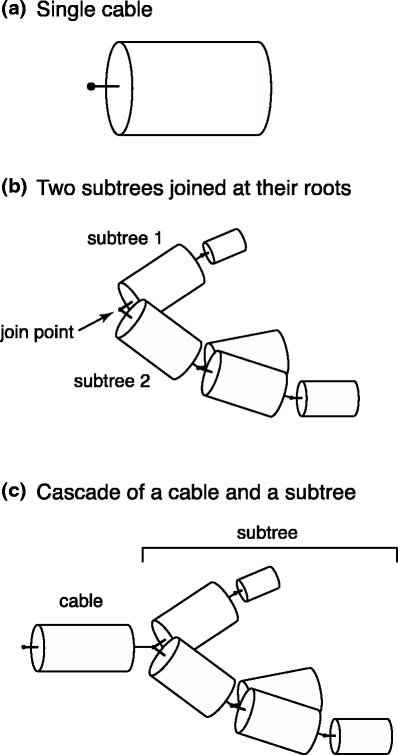

The proof proceeds by induction on cable trees. The smallest possible cable tree is a single cable segment (Fig. 3(a)), and any tree can be constructed recursively by the two operations of (1) joining two subtrees at their roots (Fig. 3(b)), and (2) cascading a cable segment with a subtree (Fig. 3(c)). We therefore first prove that the theorem holds for a single cable segment, and then prove that (1) if the theorem holds for two subtrees, it holds for the tree formed by joining them at a common point, and (2) if the theorem holds for a subtree, it holds for the tree formed by cascading a single cable segment with the subtree.

Fig. 3.

The three cases considered in the proof. (a) A single finite cable segment. (b) Two arbitrary subtrees joined at their roots. (c) A cable segment cascaded with an arbitrary subtree. In all cases, voltage is measured and current is injected at the terminal on the left-hand side, and voltage is measured with respect to the bath

Before presenting the main part of the proof, it will be useful to establish another identity involving  , namely

, namely

|

4 |

where Y(s) is the complex admittance of the cable tree, with s the complex frequency, and Y′(s) is its first derivative. To show this, we define a function that approaches  in the limit as t → ∞, given by

in the limit as t → ∞, given by

|

5 |

The Laplace transform of  is then given by

is then given by

|

6 |

where I have used the fact that  (Siebert 1986, p. 62). We can then show that

(Siebert 1986, p. 62). We can then show that

|

7 |

by substituting Y(s) V(s) for I(s), using the fact that

|

8 |

and doing some algebra. Expressing  in terms of

in terms of  , we then obtain

, we then obtain

|

9 |

|

10 |

|

11 |

|

12 |

This completes the proof that  .

.

I now show that  for a single finite cable segment. The input admittance of a finite cable segment with sealed end is given by

for a single finite cable segment. The input admittance of a finite cable segment with sealed end is given by

|

13 |

where τ

0 = r

m

c

m is the fundamental time constant of the cable,  , the input conductance of the cable if it were infinitely long, and L = ℓ/λ, the length of the cable in units of the length constant,

, the input conductance of the cable if it were infinitely long, and L = ℓ/λ, the length of the cable in units of the length constant,  (Koch and Poggio 1985, Rule I). We can then determine

(Koch and Poggio 1985, Rule I). We can then determine  for the finite cable by taking the derivative of Y(s) and evaluating at zero to find

for the finite cable by taking the derivative of Y(s) and evaluating at zero to find

|

14 |

The steady-state voltage distribution for a finite cable with a sealed end subjected to a voltage clamp at the near end (where x = 0) is given by

|

15 |

This result is given in Koch (1999, p. 34). The clamp-weighted capacitance is then given by

|

16 |

|

17 |

|

18 |

|

19 |

|

20 |

Comparing with Eq. (14), we see that  for a finite cable with a sealed end.

for a finite cable with a sealed end.

I now show that if  for two subtrees, then it holds for the tree formed by joining the two trees at their roots. If

for two subtrees, then it holds for the tree formed by joining the two trees at their roots. If  is the voltage-clamp capacitance of the first subtree, and

is the voltage-clamp capacitance of the first subtree, and  that of the second, it is easy to see that

that of the second, it is easy to see that

|

21 |

where  is the voltage-clamp capacitance of the joined tree. This is because admittances add in parallel, so

is the voltage-clamp capacitance of the joined tree. This is because admittances add in parallel, so

|

22 |

where Y(s) is the admittance of the joined tree, and the Y is are the admittances of the two subtrees. By taking derivatives on both sides of this equation and evaluating at zero, we find that

|

23 |

and so Eq. (21) follows from Eq. (4).

If we voltage-clamp the joined tree at the join point, then the steady-state distribution of voltage in each subtree will be the same as if the other subtree were absent. Thus

|

24 |

where  is the clamp-weighted capacitance of the joined tree. Thus if

is the clamp-weighted capacitance of the joined tree. Thus if  and

and  , it follows that

, it follows that  for the joined tree.

for the joined tree.

I now prove that  for a cable segment cascaded with a subtree, given that

for a cable segment cascaded with a subtree, given that  , where

, where  and

and  are the voltage-clamp capacitance and clamp-weighted capacitance of the subtree, respectively. The impedance of the cascade, Y(s), is determined by considering the cable segment as a two-port cascaded with the admittance of the subtree, Y

sub(s) (Siebert 1986, p. 84). In particular, the ABCD representation of the cable considered as a two-port is

are the voltage-clamp capacitance and clamp-weighted capacitance of the subtree, respectively. The impedance of the cascade, Y(s), is determined by considering the cable segment as a two-port cascaded with the admittance of the subtree, Y

sub(s) (Siebert 1986, p. 84). In particular, the ABCD representation of the cable considered as a two-port is

|

25 |

where  [this follows from the definition of the ABCD representation (Siebert 1986, p. 97) and from a simple application of Rule I in Koch and Poggio (1985)]. The input admittance of a two-port cascaded with a known admittance, Y

sub, is easily shown to be

[this follows from the definition of the ABCD representation (Siebert 1986, p. 97) and from a simple application of Rule I in Koch and Poggio (1985)]. The input admittance of a two-port cascaded with a known admittance, Y

sub, is easily shown to be

|

26 |

Thus the admittance of a cable segment cascaded with a subtree is given by

|

27 |

Taking the derivative of this expression with respect to s, evaluating at s = 0, and simplifying yields

|

28 |

where  is the voltage-clamp capacitance of the subtree, and G

sub is its input conductance. This expression can be simplified somewhat by putting it in terms of the input conductance of the cascade, G. We can derive an expression for G by evaluating Eq. (27) for s = 0, yielding

is the voltage-clamp capacitance of the subtree, and G

sub is its input conductance. This expression can be simplified somewhat by putting it in terms of the input conductance of the cascade, G. We can derive an expression for G by evaluating Eq. (27) for s = 0, yielding

|

29 |

Using this expression, and after some algebra, we can rewrite Eq. (28) as

|

30 |

We would now like to show that the right-hand side of Eq. (30) is equal to  . To calculate

. To calculate  for the cascade, we first solve for the steady-state distribution of voltage along the cable segment. The general expression for this is

for the cascade, we first solve for the steady-state distribution of voltage along the cable segment. The general expression for this is

|

31 |

where A and B are determined by the boundary conditions (Johnston and Wu 1995, p. 75). The boundary condition at the near end of the cable (x = 0) is determined in part by the steady-state current being injected into the cable. This is given by

|

32 |

At the far end of the cable (x = ℓ), the boundary condition involves the steady-state current leaving the cable and entering the subtree, which is given by

|

33 |

where G sub is the input conductance of the subtree.

These relations yield the following boundary conditions:

|

34 |

|

35 |

Plugging Eq. (31) into these equations, and solving for A and B yields

|

36 |

|

37 |

Plugging these expressions into Eq. (31) and invoking the hyperbolic trigonometric identities, we can then write an expression for  involving only known quantities:

involving only known quantities:

|

38 |

We can now determine an expression for  (for the cascade) based on this solution and upon Eq. (3):

(for the cascade) based on this solution and upon Eq. (3):

|

39 |

|

40 |

|

41 |

|

42 |

|

43 |

where the last step follows from the definition of  as applied to the subtree. The integral in Eq. (43) can be evaluated by substituting for

as applied to the subtree. The integral in Eq. (43) can be evaluated by substituting for  from Eq. (38) to find that

from Eq. (38) to find that

|

44 |

This can be written more compactly using the expression for G in Eq. (29) above as

|

45 |

We now substitute this expression into Eq. (43) along with the expression for v(ℓ) derived by substituting into Eq. (38), and then use the relation c m = G ∞ τ 0 / λ to arrive at

|

46 |

This expression is very similar to Eq. (30), and by invoking the inductive hypothesis that  , we can immediately conclude that

, we can immediately conclude that  for the cascade. This completes the proof that

for the cascade. This completes the proof that  for any arbitrary cable tree.

for any arbitrary cable tree.

is related to the centroid of the impulse response and Rin

is related to the centroid of the impulse response and Rin

There is an interesting relationship between  and the impulse response of the neuron in current clamp. This arises because of the close correspondence between the moments of a function and the derivatives of its Fourier transform at f = 0. In response to a current pulse, i(t) = q

0

δ(t), that delivers an amount of charge q

0, the voltage response of the neuron is

and the impulse response of the neuron in current clamp. This arises because of the close correspondence between the moments of a function and the derivatives of its Fourier transform at f = 0. In response to a current pulse, i(t) = q

0

δ(t), that delivers an amount of charge q

0, the voltage response of the neuron is

|

47 |

where z(t) is the impulse response of the system (also known as the Green’s function). The impulse response is the inverse Fourier transform of the impedance as a function of frequency, which I denote by Z f(f). (The subscript f is a reminder that Z f(·) is a function of the frequency f, not the complex frequency s.) An elementary property of the Fourier transform is that

|

48 |

where R in is the input resistance of the cell. It is easy to show that

|

49 |

|

50 |

where  , and where the last follows from the fact that Z

f(f) = 1/Y(j 2 πf).

, and where the last follows from the fact that Z

f(f) = 1/Y(j 2 πf).

The centroid of the impulse response  , which I will call τ

in, is given by

, which I will call τ

in, is given by

|

51 |

|

52 |

|

53 |

(It should be noted that τ in is just the “input delay” as defined by Agmon Snir and Segev (1993). See Section 3.)

The centroid of the impulse response is a natural way of describing the overall time scale of the neuron’s response to current input, just as the input resistance is a natural way of describing the overall magnitude of the neuron’s response to current input. It is therefore very interesting that  is the capacitance given by τ

in/R

in, and suggests that an alternative name for

is the capacitance given by τ

in/R

in, and suggests that an alternative name for  might be the “input capacitance”, because it serves as a sort of “overall” or “summary” capacitance.

might be the “input capacitance”, because it serves as a sort of “overall” or “summary” capacitance.

Relation of  to equalizing time constants

to equalizing time constants

Rall (1969) and Major et al. (1993) showed that the response of a passive nonisopotential neuron to a current step of size I 0,

|

54 |

can be written as a sum of exponential charging curves, namely

|

55 |

where the τ ks are the equalizing time constants, and the R ks are resistances, each associated with a particular time constant. This implies that the impulse response of the neuron can be written as

|

56 |

where C k = τ k/R k is a capacitance associated each equalizing time constant. Using this form for z(t), we can write R in as

|

57 |

|

58 |

In a similar fashion, we can write the first moment of z(t) as

|

59 |

|

60 |

Combining these, we have

|

61 |

|

62 |

|

63 |

This expresses  as a weighted sum of the capacitances associated with each equalizing time constant, similar to the way Eq. (58) expresses R

in as a sum of the resistances associated with each equalizing time constant.

as a weighted sum of the capacitances associated with each equalizing time constant, similar to the way Eq. (58) expresses R

in as a sum of the resistances associated with each equalizing time constant.

Discussion

I have shown that  for any arbitrary tree of passive cables. This explains exactly what is being measured by the voltage-clamp step method: a weighted sum of the total cell capacitance, where each small patch of capacitance is weighted by the square of the fraction of the voltage-clamp step “felt” by that patch. Thus

for any arbitrary tree of passive cables. This explains exactly what is being measured by the voltage-clamp step method: a weighted sum of the total cell capacitance, where each small patch of capacitance is weighted by the square of the fraction of the voltage-clamp step “felt” by that patch. Thus  includes the capacitance of the well-clamped part of the cell, but excludes the poorly clamped part, with “partly-clamped” parts of the cell being counted at a rather severe discount (because of the square). For instance, a part of the cell that only feels half of the voltage-clamp step only has one-fourth of its capacitance included in

includes the capacitance of the well-clamped part of the cell, but excludes the poorly clamped part, with “partly-clamped” parts of the cell being counted at a rather severe discount (because of the square). For instance, a part of the cell that only feels half of the voltage-clamp step only has one-fourth of its capacitance included in  .

.

As a concrete example, consider a neuron that is well-approximated by a single cable segment that is many length constants long. In this case,  is given by Eq. (19). For a long cable, the factor in parenthesis is close to one, and so

is given by Eq. (19). For a long cable, the factor in parenthesis is close to one, and so  . Since c

m is a per-unit-length quantity, this implies that

. Since c

m is a per-unit-length quantity, this implies that  is equal to the total membrane capacitance of half a length constant of cable. This illustrates the way in which

is equal to the total membrane capacitance of half a length constant of cable. This illustrates the way in which  only counts the capacitance of membrane that is electrotonically close to the point of voltage-clamp, i.e. the well-clamped part of the cell.

only counts the capacitance of membrane that is electrotonically close to the point of voltage-clamp, i.e. the well-clamped part of the cell.

Whether this discounting of poorly-clamped parts of the cell is a good thing or a bad thing depends on the circumstances. Certainly, if one wants to measure the total cell capacitance, it is a bad thing, and these results are consistent with the fact that the voltage-clamp step method cannot be used to measure total cell capacitance in a nonisopotential cell. However, if one is using the capacitance to normalize the magnitudes of currents measured in voltage clamp, one may want to measure only the capacitance of the well-clamped part of the membrane. This is a very common reason to measure neuronal capacitance, and in this case  may be preferable to a measurement of the total cell capacitance.

may be preferable to a measurement of the total cell capacitance.

All measurements of neuronal capacitance (not just the voltage-clamp step method) are based on the assumption that the neuronal response is passive. Of course, real neurons are not generally passive: they contain voltage-gated conductances, often many of them. In order to make accurate capacitance measurements, the active currents evoked by the voltage-clamp step must be small compared to the passive currents so evoked. Thus the voltage-clamp steps used to measure capacitance are best performed at potentials far from those at which voltage-gated channels are appreciably activated. If there is no window of membrane potential free from active conductances, such as might be the case if h or Kir currents (Hille 1992) are present, pharmacological blockers should be used to block any currents that might disrupt the passive response of the neuron. These techniques have been used successfully in the past to allow for measurement of capacitance and other passive properties (Hodgkin et al. 1952; Rall 1964; Major et al. 1994; Roth and Häusser 2001; Gillis 2009). Of course, if there are appreciable unblocked active currents at either the holding or the test potential, these currents will corrupt the measurement, presumably to an extent that depends on the size of the evoked active currents relative to the evoked passive current.

When recording with sharp electrodes, as in two-electrode voltage clamp, impalement generally causes a non-negligible shunt conductance to be introduced. One interesting feature of  is that it is not affected by an electrode-induced shunt conductance. This is because the net somatic conductance only contributes to the steady-state part of the voltage-clamp current, not the transient part (Eq. (2)). Another way of seeing this is to note that

is that it is not affected by an electrode-induced shunt conductance. This is because the net somatic conductance only contributes to the steady-state part of the voltage-clamp current, not the transient part (Eq. (2)). Another way of seeing this is to note that

|

64 |

and hence Y

measured′(s) = Y′real(s). Because  , we then have that

, we then have that  .

.

Whole-cell patch clamp is generally thought to introduce negligible shunt conductance, but does introduce a series resistance between the measured somatic voltage and the true somatic voltage (Roth and Häusser 2001; Jackson 1992). However,  is not strongly affected by a series resistance, even if it is uncompensated. It can easily be shown that in this case

is not strongly affected by a series resistance, even if it is uncompensated. It can easily be shown that in this case

|

65 |

where R

s is the series resistance. Thus a typical R

s/R

in ratio of ~0.01 (Gillis 2009) will lead to an error of ~2% in the measurement of  .

.

Another noteworthy point is that the proof that  does not require that the neuron’s passive properties are the same in all cable segments, nor does it require that the cable segments have cylindrical cross-sections.

does not require that the neuron’s passive properties are the same in all cable segments, nor does it require that the cable segments have cylindrical cross-sections.

The voltage-clamp step method is not the only method of measuring capacitance, although it is probably the most commonly used one (Gillis 2009; Golowasch et al. 2009). At least one popular data acquisition program (Clampex 10, Molecular Devices) has a form of this method built-in. Other commonly-used methods differ in whether they use voltage- or current-clamp, what sort of input waveform they use, and how they use the resulting output to form a capacitance estimate (Gillis 2009; Golowasch et al. 2009). Of course, these choices have consequences with regard to what part of the cell capacitance is being measured (Golowasch et al. 2009). (And for some of these methods, it is not clear what is being measured in a nonisopotential cell.) Additionally, the methods have different technical advantages and disadvantages in different settings (Gillis 2009; Golowasch et al. 2009).

As mentioned above, τ

in is just the “input delay” of Agmon Snir and Segev (1993). Among many elegant results describing signal propagation in passive dendrites in terms of temporal centroids, they showed that the centroid of the voltage response to any current input follows the centroid of the current input by the input delay (i.e. τ

in). Thus  is just the input delay over the input resistance. They also showed that when computing the delays between different points of a neuron, one could lump a subtree into a single compartment having the same input resistance and input delay (and thus the same

is just the input delay over the input resistance. They also showed that when computing the delays between different points of a neuron, one could lump a subtree into a single compartment having the same input resistance and input delay (and thus the same  ) as the subtree. This underscores the usefulness and naturalness of

) as the subtree. This underscores the usefulness and naturalness of  as a measure of neuronal capacitance.

as a measure of neuronal capacitance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grants NS17813 and MH46742, and by James S. McDonnell Foundation Grant 220020065. These grants were awarded to Eve Marder, who I thank for her generous support during this work.

References

- Agmon Snir H, Segev I. Signal delay and input synchronization in passive dendritic structures. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70(5):2066–2085. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.5.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis K. Techniques for membrane capacitance measurements. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-channel recording. 2. New Tork: Plenum; 2009. pp. 155–198. [Google Scholar]

- Golowasch J, Thomas G, Taylor AL, Patel A, Pineda A, Khalil C, et al. Membrane capacitance measurements revisited: Dependence of capacitance value on measurement method in nonisopotential neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2009;102(4):2161–2175. doi: 10.1152/jn.00160.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. 2. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF, Katz B. Measurement of current-voltage relations in the membrane of the giant axon of loligo. Journal of Physiology. 1952;116:424–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WR, Segev I, Rall W. Interpretation of time constant and electrotonic length estimates in multicylinder or branched neuronal structures. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68(4):1–20. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.4.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M. Cable analysis with the whole-cell patch clamp: Theory and experiment. Biophysical Journal. 1992;61(3):756–766. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81880-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Wu SM. Foundations of cellular neurophysiology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Khorkova O, Golowasch J. Neuromodulators, not activity, control coordinated expression of ionic currents. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(32):8709–8718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1274-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C. Biophysics of computation. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Koch C, Poggio T. A simple algorithm for solving the cable equation in dendritic trees of arbitrary geometry. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1985;12(4):303–315. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(85)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major G, Evans JD, Jack JJB. Solutions for transients in arbitrarily branching cables: I. Voltage recording with a somatic shunt. Biophyscial Journal. 1993;65:423–449. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81037-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major G, Larkman A, Jonas P, Sakmann B, Jack J. Detailed passive cable models of whole-cell recorded ca3 pyramidal neurons in rat hippocampal slices. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:4613–4638. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04613.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall W. Membrane time constants of motoneurons. Science. 1957;126:454. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3271.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall W. Theoretical significance of dendritic trees and motoneuron input-output relations. In: Reiss RF, editor. Neural theory and modeling. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1964. pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rall W. Time constants and electrotonic length of mem brane cylinders and neurons. Biophysical Journal. 1969;9:1483–1508. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(69)86467-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Häusser M. Compartmental models of rat cerebellar purkinje cells based on simultaneous somatic and dendritic patch-clamp recordings. The Journal of Physiology. 2001;535(2):445–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz DJ, Goaillard JM, Marder E. Variable channel expression in identified single and electrically coupled neurons in different animals. Nature Neuroscience. 2006;9(3):356–362. doi: 10.1038/nn1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert WM. Circuits, signals, and systems. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Swensen AM, Bean BP. Robustness of burst firing in dissociated purkinje neurons with acute or long-term reductions in sodium conductance. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(14):3509–3520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3929-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G, LeMasson G, Marder E. Selective regulation of current densities underlies spontaneous changes in the activity of cultured neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15(5):3640–3652. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03640.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]