BACKGROUND

Surveys of patients in the United States who use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and more specifically acupuncture, report users most likely to be European American, middle- or upper-middleclass, college-educated, in poorer health and female1–6. Cost of care and lack of insurance reimbursement for acupuncture can present a barrier to patients7–11.

We wanted to understand who was utilizing a free care clinic within Boston Medical Center (BMC) a large urban safety net hospital. This report analyses first visit data capturing patient profiles, types of conditions presented, and self-reports of their experience and satisfaction with acupuncture.

An academic institution, BMC is the largest safety net health care provider in New England. Seventy percent of all patients are from social and ethnic minority populations, and 30% do not speak English as a primary language 12,13. The free-care acupuncture clinic is open one time per week for a three-hour shift. Clinic providers are New England School of Acupuncture (NESA) students supervised by a NESA faculty member. To the best of our knowledge this is the first acupuncture-specific survey aimed at capturing opinions of a minority and underserved population in a hospital-based setting.

METHODS

The survey was conducted from September 2007 to September 2009 at BMC. This pilot survey was administered to 61 adult (≥ 18 years old) English-speaking patients attending an acupuncture clinic for their initial visit. The Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study.

The survey, which took approximately 20 minutes to complete, was self-administered with a research assistant available to address questions. Acupuncturists were not informed as to who took the survey and who declined participation, or as to the nature of patient responses. Patients received a $5.00 gift card for their participation.

Information on demographics and conditions was recorded. Patient satisfaction was assessed with a psychometric 5-point scale : Very Good to Very Poor. Descriptive statistics were calculated using Excel software.

RESULTS

Over a 24-month period, 61 patients were eligible and consented to participate in the study.

Demographics

Thirty-one percent of participants were male, 65% female, and 4% did not report their gender. Participants’ average age was 42.1 years old. Fourteen point seven percent of participants self-reported as Latino/a, 34.4% as black, 4.9% as multiracial, 1.6 as Asian, 1.6 % as other, 40.9% as white, and 1.9% opted not to indicate race or ethnicity (Table 1). Fifty-six percent of the participants were therefore minorities. Twenty-three percent of participants were born outside of the US in 11 different countries. Twenty-eight percent reported speaking a language other than English at home. Forty-six percent reported having attended college, 38% attended high school, 6% attended a trade school, 2% middle school, 3% reported having a master’s degree, and 5% chose not to indicate their educational background. Prior to attending either clinic 80% of participants had never had acupuncture. When asked how they found the clinic 62% percent reported a biomedical practitioner had referred them, 20% by a friend or family member and 18% did not report.

Table 1.

Demographics of our surveyed sample.

| Race | Participants N=61 |

|---|---|

| Latino/a | 14.7% |

| Black | 34.4% |

| White | 40.9% |

| Multiracial | 4.9% |

| Asian | 1.6% |

| Other | 1.6% |

| Not Reported | 1.9% |

Conditions

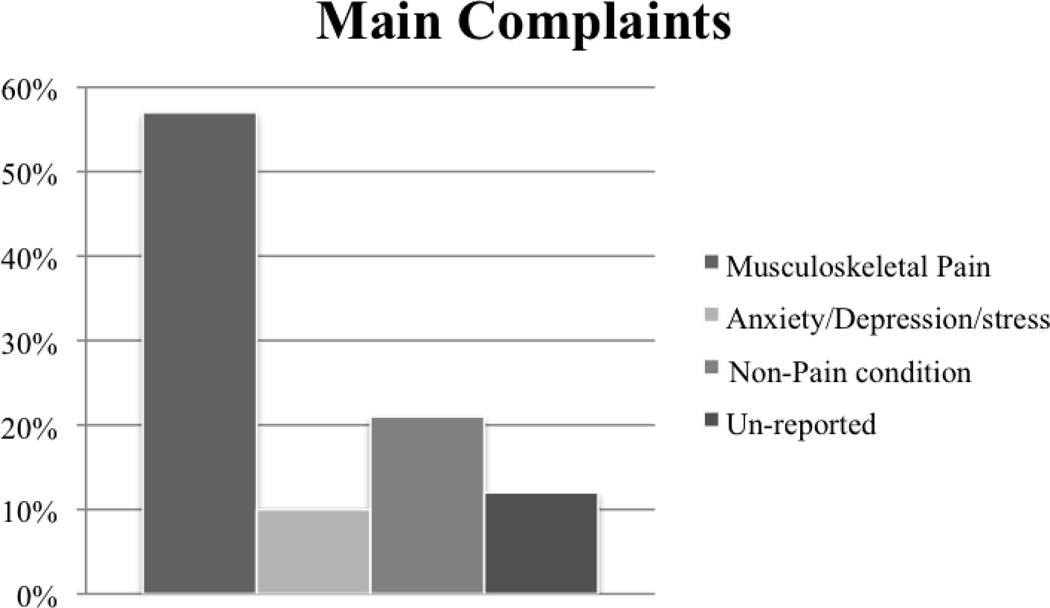

Fifty-seven percent of patient’s complaints were musculoskeletal pain, 10% reported depression/anxiety or stress, 21% reported various non-pain conditions such as insomnia, chronic fatigue, high blood pressure, nausea, asthma and a desire to stop smoking, 12% did not fill in a main complaint (Figure 1). No negative effects of acupuncture were reported on any of the surveys.

Figure 1.

Reported Conditions: Patient’s Main Complaints

Satisfaction

Positive ratings of the clinic experience were high among the vast majority of participants with 97% rating their overall experience with the acupuncture clinic as either “very good” or “good.” When asked if they would recommend acupuncture to a friend or family member, 93% of participants stated that they would do so, 5% were not sure, and 2% did not select an answer.

LIMITATIONS

This study has a number of limitations. It is small. We did not track patients over time. In the future we plan to collect such information, following patients longitudinally. The data pertaining to education may be misleading, insofar as some participants may have come from countries where a secondary school, trade school, or a four-year university might be called a college. It is therefore not entirely clear whether use of the term referred in each case to the same thing. Participant bias may have contributed to our positive results, because the service was free and they received a gift card for participating in the survey. Non-English speaking patients were treated, but they were not surveyed. Nevertheless, because 23% of those who did take part reported having been born in a country other than the United States, and 28% reported speaking a language other than English at home, this pilot data comes close to the BMC patient population, where 30% do not speak English as a primary language.

CONCLUSIONS

In this survey, a diverse population of patients sought treatment mainly for musculoskeletal conditions and were satisfied with their first visit. Future research is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

TJK was supported by a Mid-Career Investigator Award (K24 AT004095) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), National Institutes of Health. RS was supported by a Career Development Award (K07 AT002915-03) from the NCCAM. ESH was supported by the Mary B. Dunn Trust.

Thank you to the Research Assistants who so diligently helped out on this project: Maria Broderick, Jaimie Brown, Raymond Chai, Jamie Galvin, Jessica Gerber and Stephanie Kubala. Special thanks to Deirdre Kelley, Annya Pintak for their extra efforts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burke A, Upchurch DM, Dye C, Chyu L. Acupuncture use in the United States: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2006;12(7):639–648. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop FL, Lewith GT. Who Uses CAM? A Narrative Review of Demographic Characteristics and Health Factors Associated with CAM Use. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. March;7(1):11–28. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saydah SH, Eberhardt MS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with chronic diseases: United States 2002. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2006 Oct;12(8):805–812. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown CM, Barner JC, Richards KM, Bohman TM. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use in African Americans. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2007 Sep;13(7):751–758. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.6392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conboy L, Patel S, Kaptchuk TJ, Gottlieb B, Eisenberg D, Acevedo-Garcia D. Sociodemographic determinants of the utilization of specific types of complementary and alternative medicine: an analysis based on a nationally representative survey sample. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2005 Dec;11(6):977–994. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackenzie ER, Taylor L, Bloom BS, Hufford DJ, Johnson JC. Ethnic minority use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): a national probability survey of CAM utilizers. Alternative therapies in health and medicine. 2003 Jul–Aug;9(4):50–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao MT, Wade CM. Socioeconomic factors and women's use of complementary and alternative medicine in four racial/ethnic groups. Ethnicity & disease. 2008 Winter;18(1):65–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Highfield ES, Barnes L, Spellman L, Saper RB. If you build it, will they come? A free-care acupuncture clinic for minority adolescents in an urban hospital. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2008 Jul;14(6):629–636. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kronenberg F, Cushman LF, Wade CM, Kalmuss D, Chao MT. Race/ethnicity and women's use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: results of a national survey. American journal of public health. 2006 Jul;96(7):1236–1242. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chao MT, Wade C, Kronenberg F, Kalmuss D, Cushman LF. Women's reasons for complementary and alternative medicine use: racial/ethnic differences. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2006 Oct;12(8):719–720. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryder PT, Wolpert B, Orwig D, Carter-Pokras O, Black SA. Complementary and alternative medicine use among older urban African Americans: individual and neighborhood associations. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008 Oct;100(10):1186–1192. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Accessed 2/20/10]; http://www.bmc.org/Documents/BMC-Facts-2009.pdf.

- 13. [Accessed 7/1/10]; http://www.bmc.org/Documents/WhatMakes_BMC_Special_Brochure.pdf.