Abstract

This article discusses the crucial role of teaching and learning communication skills for general practitioners, based on the theory of experiential and self-directed learning. It also outlines the proposed ways and methods to teach these communication skills in this project.

The patient-doctor interview or what is known as office visit in some countries and consultation in others is the cornerstone of the entire General Practice (GP) or Family Medicine. It is from this process and outcome that the reputation is gained or destroyed. The analysis of the consultation is complicated and varied but is most usefully employed to assess effecacy in terms of achieving the means that are mutually desired by patients and their carers.

Introduction

This paper discusses the crucial role of teaching and learning communication skills for general practitioners, based on the theory of experiential and self-directed learning. It also outlines the proposed ways and methods to teach these communication skills in this project.

The patient-doctor interview or what is known as office visit in some countries and consultation in others is the cornerstone of that entire General Practice (GP) or Family Medicine. It is from this process and outcome that reputations are gained or destroyed. The analysis of the consultation is complicated and varies but is most usefully employed to assess the effectiveness in terms of achieving the means that are mutually desired by patients and their carers.

Why teaching and learning communication skills

Doctors often pursue a "doctor-centred" closed approach to information gathering that may discourage patients from telling their story or voicing their concerns.1 Stewart found that 54% of patient’s complaints and 45% of their concerns were not elicited.2 On the other hand, Stewart, Arborelius and Bremberg found that great patient centeredness in interviews lead to greater patient satisfaction.3,4 This emphasizes the fact that communication is a core clinical skill that is an essential part of clinical competence.5,6 Teaching and transferring the essential communication skills is a unique process and may not always be properly delivered by teachers of core medical subjects such as cardiology. It is wrong to assume that those who are competent medical teachers are automatically equipped to teach communication skills. In addition, the form of communication skills needed differ from one region to another. Therefore, it is important for teachers of communication skills to be aware of the regional needs, for instance it is important for practicing doctors resident in North America to understand communication and interviewing skills needed for North America.

The Self-Directed Learning Theory and Experimental Learning

The self- directed learning theory is based on a process in which individuals take the initiative with or without the help of others in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating their learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies and evaluating learning outcomes. This theory is often preferred because it is more in tune with humans’ natural process of psychological development. This process, at the start, makes humans totally dependent on their parents than on their teachers and finally, through gradual increase in responsibility, they mature and become self-directing.7 This effective development strategy can be used either in teaching or learning by setting goals and following the learning chain for one’s own learning or for teaching others.8

Another theory discussed here is the experiential learning theory.9 This method appears to be more effective for teaching and learning communication skills. Knowles found that adults enter into any mission with a different background of experience from that of their youth.10 Having lived longer, they have accumulated a greater volume of experience that are used in learning new skills.10

As a result of experimental learning, a rift between the experiences of children and adults emerge resulting in:

Adults have broader foundation of experiences.

Adults have more to contribute to the learning of others.

Adults are less open-minded as they have acquired a larger number of fixed habits and patterns.

For effective learning and teaching of communication skills using the experiential learning approach, the following elements are critical:

• clear delineation and definition of the required skills,

• observation,

• well-intentioned, detailed and descriptive feedback,

• reviews using video or audio recording,

• practice and rehearsal of the required skills,

• active learning in a small-group or one-to-one.

Selecting the Best Teaching and Learning Practice

To select the appropriate method to use for learning or teaching requires some understanding of the challenges and rewards each of the previously mentioned methods. Through the evaluation of all these factors a decision to select either the self-directed, experimental or even didactic method for developing the required communication skills can be made.

• Experiential learning methods are potentially the most challenging and rewarding. Once successfully implemented, these methods lead to deeper discussion or understanding and entail action or change in behaviour. The stages of these methods are captured in the old Chinese proverb

I hear and I forget

I see and I remember

I do and I understand

So by analysing the proverb it can be seen that the first step is observation followed by practice. Therefore, by doing it or watching somebody else doing it, one will reach a "descriptive feedback" stage, which is an essential element of learning experiential communication skills.

To test this in practice, a three day workshop (see table 1) was organized which focused on three of the essential elements for learning and teaching communication skills discussed in the previous section: role play, group discussions and video recorded interviews.

Table 1. 3 Days Workshop Schedule for Communication skills.

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|

| - (08.00-09.30) Introduction lecture on different communication skills models. - (09.30-10.00) Group discussion - (10.00-10.30) Break - (10.30-11.00) How to do learning contract? - Videotape Review. - Afternoon session is set for external research and reading Set task: recorded video tape of consultation of their own to be brought on day 2. |

- (08.00-08.15) submission of learning contract - (08.15-09.30) Role play exercise - (09.30-10.00) Break - (10.30 -11.00) Special Topics Topic: 1- braking bad news Topic: 2- difficult patient Topic: 3- patient with U.R.T.I demanding antibiotics. Each topic followed by group discussion |

- (08.00-08.30) videotape selection for discussion. - (8:30- 10:00) first videotape review - (10.00-10.30) Group discussion - (10.30-11.00) Break - (11.00-12.30) second videotape review. - (12.30-01.00) Group discussion - (01.00-0.2.00) Lunch - (02.00-03.00) Workshop review and completion of evaluation questioner. |

| Materials - Handout of learning contract - Colour markers - Power point presentation, projector and blackboard - Flip chart - Web page |

Materials - Case scenarios - Chairs and table - Flip chart - Markers - Overhead projector |

Materials - TV, video - Flip chart - Pencils - Questioner |

According to Kolb’s cycle, experiential learning occurs through a repeated series of four steps:

Concrete experience: encountered when the learner is involved in a specific experience, in a given real-life situation, presenting problem to be resolved through the application of new knowledge. The learner, following such an encounter, has to engage through experience.

Reflective observation: the learner reflects on this experience from different points of view to give it meaning arriving at an intuitive understanding of the reality at hand. In order to solidify that understanding and define it in terms that may lead to action the learner and then to engage in it.

Abstract conceptualization: the learner integrates the meaning from the experience with those from other personal experiences to develop a personal concept.

Active experimentation: the learners’ conclusion is used to guide decision-making, planning and implementation".11

According to Smith & Kolb the process of experiential learning is very effective.12 The learner needs, to be able to adapt to all four steps; concrete experience (CE), reflective observation (RO), abstract conceptualization (AC) and active experimentation (AE).

In the first stage of the learning cycle, a person relies on their CE abilities (Kolb 1985).13 CE abilities emphasize personal involvement with individuals in ‘everyday’ situations. This was investigated during the workshop using a video recorded interview with a patient. During this stage learning occurs through capturing the objectives of the interview.

Learning by watching and listening occurs in the second stage (RO). In the AC stage, the learner learns by thinking and analyzing the interview from the videotape and in AE, learning takes an active form, and the learner learns by doing it either in-group discussion or in a role play. During the practice, all participants had an opportunity to repeat this cycle by doing a role play. The advantage of the role-play is that it has a spiral form and it was repeated many times, which improved the learning and teaching of communication skills.• Problem-based learning methods: Knowle’s learning theory suggests that adult learners are motivated to learn when they perceive learning to be relevant to their current situation and when they can be applied to the real world with immediate impact on practical issues they have.10 Learners are therefore motivated by a problem-based (rather than a subject-based) approach. However, some practical difficulties occur when they themselves are needed to act as experienced stimulus for others’ learning.

In general, adults are motivated by learning, which is:

Relevant to their present situations

Practical rather than just theoretical

Problem rather than subject centred

Builds on learners’ previous experiences

Directed towards learners perceived needs

Planned in terms of negotiated and emergent objectives

Participatory, actively involving learners

Self-directed

Designed so that learners can take responsibility for their own learning

Designed to promote equal relationship with teachers

Evaluated through self and peer assessment.

So to maximize learning, an important aspect is to encourage problem-based approaches, starting from where learners are, and attempt to address their needs making teaching and learning relevant to their situation and this can be done by discovering learners’ perceived needs through asking what problems and difficulties they are experiencing and what areas they would like help in. This can also be enhanced through creating supporting climate where learners collaborate rather than compete. A further improvement can be achieved by developing appropriate experiential material, like videotapes brought by the learners themselves of their interaction with patients.

Another means of improving the learning using the problem-based approach is to analyze the actual consultation, either using videotapes or in the role play which was used in the three day workshop-and finding out about problems they experienced and what help they would like from the rest of the group. In addition, questions on additional issues needed to be discussed were raised. This makes problem-based learning beneficial for enhancing teamwork and peer communication skills and supporting self-assessment and life-long learning. These all encouraged independence to meet identified learning goals and stimulate critical thinking and therefore reach an evidence-based decision-making stage.

• The Didactic method: this method includes lectures, group presentations and reading. The Didactic method enables learners to understand what it takes to communicate effectively but does not develop learners’ skills or ensure mastery or application in practice. It is thought that it is important to have awareness on what communication skills entails, as it is an essential part of knowledge implementation. Therefore, before the start of the workshop if one or two trainees lacked the necessary awareness of communication skills, the planned lectures helped them understand the aims and objectives of the workshop. This also helped them build their own learning contract and making tier their own goals. The lectures also helped them understand the different type of models used for teaching and learning communication skills which they could research and implement on their own in the future. It is important to realize that knowledge of the fundamentals of communication skill and the integral relationships between the various communication skills is also extremely important. Understanding the logical connection between various skills and how they can be used together in different parts of the consultation can both enhance learning and enable the skills to be used more constructively in the interview.

Understanding different types of models

In this section, a summary of the approach used in learning and teaching different communication skills models is presented. These models were used during the workshop.5,6,14,15 The approach used was as follows:

Description of events occurring in a consultation by Byrne and Long.1

The 7 tasks model by Pendleton, Schofield, Tate, and Havelock. It lists 7 tasks, which form an effective consultation. The model emphasizes the importance of the patient’s view and understanding of the problem.14

(The Inner Consultation) This work by Roger Neighbour looks at improving consultation skills.15

The Calgary Cambridge Guide to Consultation by J Silverman, S Kurtz, J Draper; this is a very sophisticated but practical tool for assessing consultations by examining stated behaviours and task completion.6 Although it looked most daunting it is worth persevering with. It was well researched, evidence-based and patient centred. In addition, it is a more detailed model, well explained and when followed by any physician, excellent consultation skills will be acquired but it needs a lot of practice to achieve an expert status in consultation. Nevertheless, the approach is easy to understand and implement.

What is clearly apparent from all the approaches is that most of them have been applied in the U.K and North America and may not be effective in different cultures like the Gulf countries, Africa or Asia. This is a separate research subject that should be looked at in the future. (More detail about these modules is given in appendix 1)

Workshop Design

The workshop implemented self-directed learning and experiential learning through videotape and role-play methods and the didactic methods through the introduction of lectures about the different models of communication skills. As this workshop was designed for GPs in Oman, it was focused on learning the foundations of experiential learning, which was covered by the trainees bringing their own-recorded interviews.16-28 This may have been intimidating and threatening to the attendees but was worth experimenting. A questioneer at the end of the workshop was used to assess the impact of using such a method in Oman.

During the workshop most of Knowles’ (1980) principle guidelines that were implemented included:

"Establishing an effective learning climate, where learners feel safe and comfortable expressing themselves.

Involving learners in mutual planning of relevant methods and curricular content.

Involving learners in diagnosing their own needs, this helped to trigger internal motivation.

Encourage learners to formulate their own learning objectives-this gave them more control of their learning.

Encouraging learners to identify resources and devise strategies for using the resources to achieve their objectives.

Support learners in carrying out their learning plans

Involve learners in evaluating their own learning; this can develop their skills of critical reflection.8 (Knowles).

These principles were followed during the workshop through the lectures on communication skills and group discussions. This gave the trainees a chance to express themselves and interact with the other trainees. This helped to create a safe and comfortable environment during the workshop. Principle (1) effectively includes the learning contract and searching for the information, which were conducted during days 1 and 2. Principles 2-6 were implemented during day 2. Principles 4,6,7, which included the role-play, recorded interview and group discussion methods were implemented on day 2. The main focus of day 3 was to allow the trainees to choose the problem they preferred to discuss, which may be the difficulties with patients that they most encounter. The details about each sessions are given below.

Day 1

Morning Session (1) The workshop started with introductory lectures about communication skills and the different models in communication skills. This introduced those who lacked the necessary background in communication skills and brought them on board during the practical sessions. Understanding the logical connection between various skills and how they can be integrated in different parts of the consultation can both enhance learning and enable the skills to be used more constructively in the interview.

Morning Session (2) The second part of day 1 focused on group discussion regarding the need to learn communication skills and the difficulties to expect while learning. In between the two sessions, the participants were asked to complete a learning contract, giving them the examples and references of the learning contract forms and handouts.

The learning contract is an important tool for adult learning, as they need to develop a criteria by which they can judge their own performance and it is a form of self-directed learning. The merits of self-directed learning were discussed previously in this article. This method is more in tune with the nature of processes of psychological development. Therefore, it can be used either in teaching or learning by setting-out the goals and using the learning contract for the trainer or the trainee. This was covered in more detail on Day 3. The contract was also intended to be used for later correspondence with the trainees. The second session also included videotape of recorded consultations, in addition to the group discussion to review problems and difficulties that were likely to be experienced and what solutions may be found. Usually, videotapes are more comfortable for the trainee.

During the second session, problem-based learning was discussed in more details in the previous sections – was implemented. The key problem-based learning techniques intended for days 1 and 2 were those described by Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning which occur through a repeated series of four steps:

Concrete experience

Reflective observation

Abstract conceptualization

Active experimentation

These were applied either during the role-play, videotape and recorded video tape of the patient interview processes. At the end of day 1, the trainees were asked to bring a recorded video tape of a consultation of their own (if they had one) on day 2. Extra reading material is available in listed textbooks and on the web for the trainees to research. The afternoon of day 1 was intended for work outside the main workshop schedule. This was intended to be part of self-directed learning to be covered in more detail on days 2 and 3. The research and self-directed training times were also intended to keep the trainees focused on the discussion.

Day 2

Morning session: The first part of day 2 implemented the role-play technique where the instructor acted as a patient. The doctor’s roles was always played by one of the trainees. Three topics were intended:

Topic 1: breaking bad news

Topic 2: difficult patient

Topic 3: patient with U.R.T.I demanding antibiotics.

These are thought to be among the most common cases that a GP has to deal with. Each topic was followed by group discussion. The role-play method was chosen because it is inexpensive and each trainee had the opportunity to be a doctor and a patient.

As with day 1, the afternoon of day 2 was left for self-directed learning using listed books or material on the web.

Day 3

This was intended to be the longest day of the workshop and was divided into 4 sessions:

Session 1: A selection of 2 videotapes from the trainee of recorded interviews with a patient were made. A short session is dedicated to this due to its importance as it supplements the need for performing a doctor-patient interview while being assessed, which can be uncomfortable. Using the videotapes, the trainees learned how to overcome common problems by following the principle of adult learning, which helped reduce any defensiveness that they may have and will enable them to benefit from the extra communication training.

Session 2: The first videotape session was performed and Knowles (1980) principles guideline on how to teach learners who tend to be independent and self-directed.10

Session 3: The second selected videotape was reviewed and followed by a group discussion. In the discussion, the trainees were requested to outline the most important problems they faced which were discussed and potential solutions were also discussed.

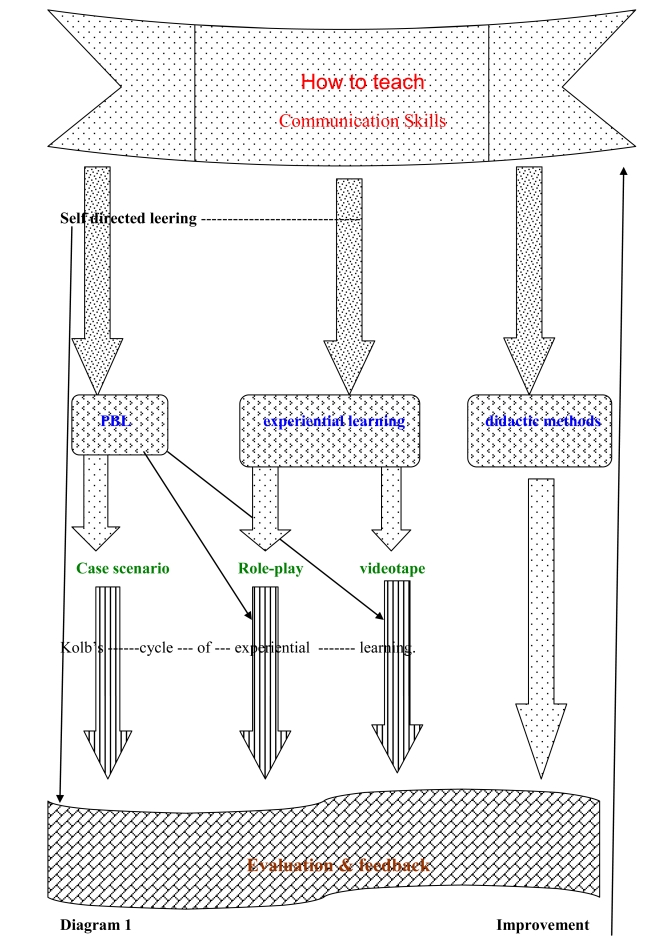

Session 4 This session was dedicated to group filling in evaluation forms and exchanging views on the gained experiences through shared training. The gained feedback is important for future workshop improvements. What points were missed, all this is important feedback. (Details on the workshop timing and material is found in table1 and Figure 1 shows a diagram on how to teach).

Figure 1.

Diagram on how to teach

Conclusion

Communication skills are important in the view of good health care and more patient satisfaction.25,28 Communication skills should be taught at medical student level and may be conducted for GPs. It is recommend that communication skills be part of Oman’s medical curriculum.

Self-directed learning gives broader horizons for the learner and the teacher so that they are able to understand the problem and find the appropriate solutions. Self-directed learning is useful, convenient, less stressful and more objective. Using this process, learners can progress at their own pace and can review the material needed. The educator must also believe in Self-directed learning for it to be successful and must believe in the principle of adult education. On the other hand, experiential learning is flexible and challenging but may be intimidating or even threatening, hence, may not be appropriate at all times. To make this method more acceptable, the facilitator or the instructor should consider the climate of the class and also adopt methods that can break the ice between the participants by leading them to introduce themselves first in order to know each other, which could lead to having an environment of collaboration rather than competition.

There are some factors that can influence the outcome of Kolb’s cycle of experiential learning; for example, the personality of the learners, their work experience, their knowledge level and the teaching ability of the preceptor. All these should be taken into account during workshops or courses.

By the end of the workshop, participants should be able to discuss different types of consultation models which can be used during consultations. The input from the workshop can be incooperated into future workshops planned for GPs in Oman.

Description of events occurring in a consultation (after Byrne and Long 1976)

This model was produced after analyzing over 2,000 tape recordings of consultations. They identified six phases that form a logical structure to the consultation:

The Doctor establishes a relationship with the patient,

The Doctor either attempts to discover, or actually discover, the reason for the patients’ attendance.

the doctor conducts a verbal, or physical examination, or both,

the doctor, or the doctor and the patient, or the patient (usually in that order of probability) consider(s) the condition,

the doctor, and occasionally the patient, details treatment or further investigation,

the consultation is terminated, usually by the doctor.

The 7 tasks model by Pendleton, Schofield, Tate, and Havelock:

It lists 7 tasks, which form an effective consultation. The model emphasizes the importance of the patient’s view and understanding of the problem.

To define the reasons for the patient’s attendance, including: the nature and history of the problem causing the patients to have concerns and expectations in view of the problems.

-

To consider other problems:

Continuing problems

At risk factors.

To choose with the patient an appropriate action for each problem.

To achieve a shared understanding with the patient.

To involve the patient in the management plan and encourage them to accept appropriate responsibility.

To use time and resources appropriately.

To establish or maintain a relationship with the patient which helps to achieve other tasks.

The Inner Consultation

This work by Roger Neighbour looks at improving consultation skills.

The following formats for the consultation are discussed.

Connecting: Rapport building skills

Summarizing: Listening and eliciting skills

Handover: Communicating skills

Safety netting: Predicting skills

Housekeeping: Taking care of yourself, checking you are ready for the next patient.

The Calgary Cambridge Guide to Consultation (J Silverman, S Kurtz, J Draper)

This is a very sophisticated but practical tool for assessing consultations by examining stated behaviors and task completion. Although it seems daunting, it is worth persevering with. It is well researched, evidence based and patient centred.

The system consists of a five part STRUCTURE, from which is derived a FRAMEWORK for a series of SKILLS and finally a list of 55 BEHAVIOURS.

The Structure

Initiating the Session.

Gathering Information.

Building the Relationship.

Explanation and Planning.

Closing the Session.

The Framework

Initiating the Session.

Establishing initial rapport / Identifying the reason for the consultation.

Gathering Information.

Exploration of problems.

Understanding the patients’ perspective.

Providing structure to the consultation.

Building the Relationship

Developing rapport / Involving the patient.

Explanation and Planning.

Providing the correct amount and type of information.

Aiding accurate recall and understanding.

Achieving a shared understanding, incorporating the patient’s perspective

Planning: shared decision-making.

Closing the Session.

The Skills

Initiating the session.

Establishing initial rapport.

Greeting / Introductions / Interest, concern and respect.

Identifying the reasons for the consultation.

The opening question.

Listening to the patient’s opening statement.

Screening.

Agenda setting

Gathering information.

Exploration of Problem.

Patient’s narrative.

Question Style.

Listening.

Facilitative response.

Clarification.

Internal summary.

Language

Understanding the Patient’s Perspective.

Ideas and Concerns.

Effects.

Expectations.

Feelings and thoughts.

Cues.

Providing Structure to the Consultation.

Internal summary / Signposting / Sequencing / Timing.

Building a relationship.

Developing a rapport.

Non-verbal behavior.

Use of notes.

Acceptance.

Empathy and support.

Sensitivity.

Involving the Patient.

Sharing of thoughts / Providing rational / Examination.

Explanation and planning.

Providing the correct amount and type of Information.

Chunks and checks.

Assess the patient’s starting point.

Asks the patient what other information would be helpful.

Gives explanation at appropriate time.

Aiding accurate recall and understanding.

Organised explanation.

Using explicit categorisation or signposting.

Using repetition and summarizing.

Language.

Using visual methods of conveying information.

Checking patient’s understanding of information given.

Achieving a shared understanding and incorporating the patient’s perspective.

Relating explanation to the patient’s illness framework.

Providing opportunity and encouraging the patient to contribute.

Picking up verbal and non-verbal cues.

Eliciting patient’s beliefs, reactions and feelings.

Planning: shared decision-making.

Sharing own thoughts.

Involving patient by making suggestions rather than directives.

Encouraging patient to contribute their thoughts.

Negotiating / Offering choices / Checking with patient.

Closing the Session

End summary.

Contracting.

Safety Netting.

Final checking.

Acknowledgements

The authors reported no conflict of interest no funding has been received on this work.

References

- 1.Byrne PS, Long BE. Doctors talking to patients. London, England: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart MA, McWhinney IR, Buck CW. The doctor/patient relationship and its effect upon outcome. J R Coll Gen Pract 1979. Feb;29(199):77-81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart MA. What is a successful doctor-patient interview? A study of interactions and outcomes. Soc Sci Med 1984;19(2):167-175 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90284-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arborelius E, Bremberg S. What can doctors do to achieve a successful consultation? Videotaped interviews analysed by the ‘consultation map’ method. Fam Pract 1992. Mar;9(1):61-66 10.1093/fampra/9.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for communication with patients. Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurtz S, Silverman J, Draper J. Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine. Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Candy PC. Self-direction for lifelong learning: a comprehensive guide to theory and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufman DM. Applying educational theory in practice. BMJ 2003. Jan;326(7382):213-216 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolb DA. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles M. Modern practice of adult education: from pedagogy to andragogy. Revised. Englewood Cliftts NJ: prentice Hall, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackeracher D. Making sense of adult learning. Culture concept Inc. 1986, p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith DM, Kolb DA. LSI User’s guide. Boston: McBer & Company, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolb DA. Learning style inventory (revised edition). Boston: McBer, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, Havelock P. The consultation: An approach to learning and teaching. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neighbour R. The inner consultation: How to develop an effective and intuitive consulting style. Petroc Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balint M. The Doctor, his patient and the illness. London: Tavistock Publications, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maslow AH. Motivation and Personality. 2nd ed New York:Harper & Row, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kompf M, Barer-Stein T. The craft of teaching adults. Irwin Publishing, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rollnick S, Kinnersley P, Butler C. Context-bound communication skills training: development of a new method. Med Educ 2002. Apr;36(4):377-383 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmboe ES. Faculty and the observation of trainees’ clinical skills: problems and opportunities. Acad Med 2004. Jan;79(1):16-22 10.1097/00001888-200401000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper V, Hassell A. Teaching consultation skills in higher specialist training: experience of a workshop for specialist registrars in rheumatology. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002. Oct;41(10):1168-1171 10.1093/rheumatology/41.10.1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer AW, Düsman H, Tan LH, Jansen JJ, Grol RP, van der Vleuten CP. Acquisition of communication skills in postgraduate training for general practice. Med Educ 2004. Feb;38(2):158-167 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01747.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watzlawick P. The Language of Change. New York: Basic Books 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bendix T. The Anxious Patient. Edinburgh: Churchill livingstone 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levenstein JH, McCracken EC, McWhinney IR, Stewart MA, Brown JB. The patient-centred clinical method. 1. A model for the doctor-patient interaction in family medicine. Fam Pract 1986. Mar;3(1):24-30 10.1093/fampra/3.1.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henbest RJ, Stewart MA. Patient-centredness in the consultation. 2: Does it really make a difference? Fam Pract 1990. Mar;7(1):28-33 10.1093/fampra/7.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown JB, Weston WW, Stewart MA. Patient-centred interviewing. Part II: finding common ground. Can Fam Physician 1989. Jan;35:153-157 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stott NC, Davis RH. The exceptional potential in each primary care consultation. J R Coll Gen Pract 1979. Apr;29(201):201-205 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]