Abstract

Background & Aims

The effects of trypsin on pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (PDEC) vary among species and depend on localization of proteinase-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2). Bicarbonate secretion is similar in human and guinea pig PDEC; we compared its localization in these cell types and isolated guinea pig ducts to study the effects of trypsin and a PAR-2 agonist on this process.

Methods

PAR-2 localization was analyzed by immunohistochemistry in guinea pig and human pancreatic tissue samples (from 15 patients with chronic pancreatitis and 15 without pancreatic disease). Functions of guinea pig PDEC were studied by microperfusion of isolated ducts, measurements of intracellular pH (pHi) and Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i, and patch clamp analysis. The effect of pH on trypsinogen autoactivation was assessed using recombinant human cationic trypsinogen.

Results

PAR-2 localized to the apical membrane of human and guinea pig PDEC. Trypsin increased [Ca2+]i and pHi, and inhibited secretion of bicarbonate by the luminal anion exchanger and the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cl- channel. Autoactivation of human cationic trypsinogen accelerated when the pH was reduced from 8.5 to 6.0. PAR-2 expression was strongly down-regulated, at transcriptional and protein levels, in the ducts of patients with chronic pancreatitis, consistent with increased activity of intraductal trypsin. Importantly, in PAR-2 knockout mice, the effects of trypsin were PAR-2 dependent.

Conclusions

Trypsin reduces pancreatic ductal bicarbonate secretion via PAR-2–dependent inhibition of the apical anion exchanger and the CFTR Cl- channel. This could contribute to the development of chronic pancreatitis, decreasing luminal pH and promoting premature activation of trypsinogen in the pancreatic ducts.

Keywords: acinar cells, ductal epithelium, animal model, pancreatic enzymes, chronic, acute, ion channel, ion transporter

INTRODUCTION

Trypsinogen is the most abundant digestive protease in the pancreas. Under physiological conditions trypsinogen is synthesised and secreted by acinar cells, transferred to the duodenum via the pancreatic ducts and then activated by enteropeptidase in the small intestine1. There is substantial evidence that early intra-acinar2,3 or luminal4,5 activation of trypsinogen to trypsin is a key and common event in the development of acute and chronic pancreatitis. Importantly, almost all forms of acute pancreatitis are due to autodigestion of the gland by pancreatic enzymes6.

Several studies have demonstrated that trypsin stimulates enzyme secretion from acinar cells via PAR-27,8, whereas the effect of trypsin on pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (PDEC) is somewhat controversial. Trypsin activates ion channels in dog PDEC9 and stimulates bicarbonate secretion in the CAPAN-1 human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line10; whereas, it dose-dependently inhibits bicarbonate efflux from bovine PDEC11. The effect of trypsin differs not only among species, but also with respect to the localization of PAR-2. When PAR-2 is localized to the basolateral membrane and activated by trypsin, the result is stimulation of bicarbonate secretion9,10. In contrast, when the receptor is localised to the luminal membrane, the effect is inhibition11. Interestingly, there are no data available concerning the effects of trypsin on guinea pig PDEC which, in terms of bicarbonate secretion, are an excellent model of human PDEC12.

The human pancreatic ductal epithelium secretes an alkaline fluid that may contain up to 140mM NaHCO312,13. The first step in HCO3- secretion is the accumulation of HCO3- inside the cell, which is driven by basolateral Na+HCO3- co-transporters, Na+/H+ exchangers and H+-ATPases12,13. Only two transporters have been identified on the apical membrane of cells in the proximal ducts that are the major sites of HCO3- secretion; cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and the solute carrier family 26 (SLC26) anion exchangers12,13. How these transporters act in concert to produce a high HCO3- secretion is controversial14. Most likely, HCO3- is secreted on the anion exchanger until the luminal concentration reaches about 70mM, after which the additional HCO3- required to raise the luminal concentration to 140mM is transported via CFTR15,16.

The role of PAR-2 in experimental acute pancreatitis is also controversial and highly dependent on the model of pancreatitis studied. PAR-2 was found to be protective in secretagogue-induced pancreatitis in mice7,17-19 and rats20. However, PAR-2 is clearly harmful when pancreatitis is evoked by the clinically more relevant luminal administration of bile salts in mice17.

In this study, we show for the first time that (i) PAR-2 is localized to the apical membrane of the human proximal PDEC, (ii) the localization of PAR-2 in the guinea pig pancreas is identical to the human gland, (iii) trypsin markedly reduces bicarbonate efflux through a dihydro-4,4’-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2’-disulfonic acid (H2DIDS)-sensitive apical SLC26 anion exchanger and strongly inhibits CFTR, (iv) a decrease in pH within the ductal lumen will strongly accelerate the autoactivation of trypsinogen, and (v) trypsin down-regulates PAR-2 expression at both transcriptional and protein levels in PDEC of patients suffering from chronic pancreatitis.

METHODS

A brief outline of the materials and methods are given below. For further details, please check the supplementary material.

Solutions

The compositions of the solutions used for microfluorimetry are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of solutions for microfluorimetry studies

| Standard HEPES |

Standard HCO3- |

Cl--free HCO3- |

Ca2+-free HEPES |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 130 | 115 | 132 | |

| KCl | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| MgCl2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| CaCl2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Na-HEPES | 10 | 10 | ||

| Glucose | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| NaHCO3 HEPES | 25 | 25 | ||

| Na-gluconate | 115 | |||

| Mg-gluconate | 1 | |||

| Ca-gluconate | 6 | |||

| KH2-sulfate | 5 |

Values are concentrations in mM.

Isolation of pancreatic ducts and individual ductal cells

Small intralobular proximal ducts and individual ductal cells were isolated from guinea pigs or PAR-2 wild-type (PAR-2+/+) and knock-out (PAR-2-/-) mice with a C57BL6 background by microdissection as described previously21.

Measurement of intracellular pH and Ca2+ concentration

Intracellular pH (pHi) and calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) were estimated by microfluorimetry using the pH- and Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dyes BCECF-AM and FURA 2-AM, respectively.

Microperfusion of intact pancreatic ducts

The luminal perfusion of the cultured ducts was performed as described previously22

Electrophysiology

CFTR Cl- channel activity was investigated by whole cell patch clamp recordings on guinea pig single pancreatic ductal cells.

Measuring autoactivation of trypsinogen

Autoactivation of human cationic trypsinogen was determined in vitro at pH values ranging from 6.0 to 8.5. Experimental details are described in the supplementary materials.

Immunohistochemistry

Five guinea pig, two PAR-2+/+, two PAR-2-/- and 30 human pancreata were studied to analyse the expression pattern of PAR-2 protein. Relative optical densitometry was used to quantify the protein changes in the histological sections. Patients’ data and the full methods are described in the supplementary materials.

Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was isolated from 30 human pancreata. Following reverse transcription, mRNA expression of PAR-2 and β-actin were determined by real-time PCR analysis.

RESULTS

Expression of PAR-2 in guinea pig and human pancreata

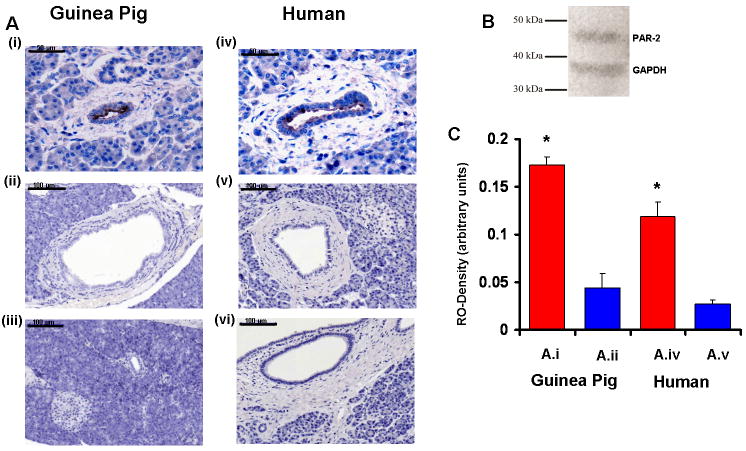

PAR-2 was highly expressed in the luminal membrane of small intra- and interlobular ducts (Fig.1A.i; cuboidal epithelial cells forming the proximal pancreatic ducts), but was almost undetectable in the larger interlobular ducts (Fig.1A.ii; columnar epithelial cells forming the distal pancreatic ducts). The localization of PAR-2 in the human pancreas was identical to that in the guinea pig gland (Fig.1A.iv-vi). Measurements of relative optical density confirmed the significant differences between the expression of PAR-2 in small intra- and interlobular ducts and the larger interlobular ducts in both species (Fig.1C).

Figure 1. Localization of PAR-2 on human and guinea pig pancreatic ducts.

Light micrographs of guinea pig (Ai-iii) and human (Aiv-vi) pancreas are shown.i)PAR-2 is localized to the luminal membrane of PDEC in small intra- and interlobular ducts (X400).ii) Large interlobular ducts do not express PAR-2 (X200).iii) No primary antiserum (X200).iv-v) Sections from human pancreas exhibit a similar localization of PAR-2 compared to the guinea pig gland (X400;X200).vi) No primary antiserum (X200).B) Western blot analysis was used to determine the specificity of the PAR-2 antibody. Polyclonal anti-PAR-2 demonstrated a single 44kDa band.C)Quantitative measurement of relative optical densities (RO-Density) of small intra- and interlobular ducts (A.i,iv), and large interlobular ducts (A.ii,v) are shown.n=12.*:P<0.05 vs. A.ii or A.v, respectively. Scale bar=50 μm on A.i,iv; 100 μm on A.ii-iii and A.v-vi.

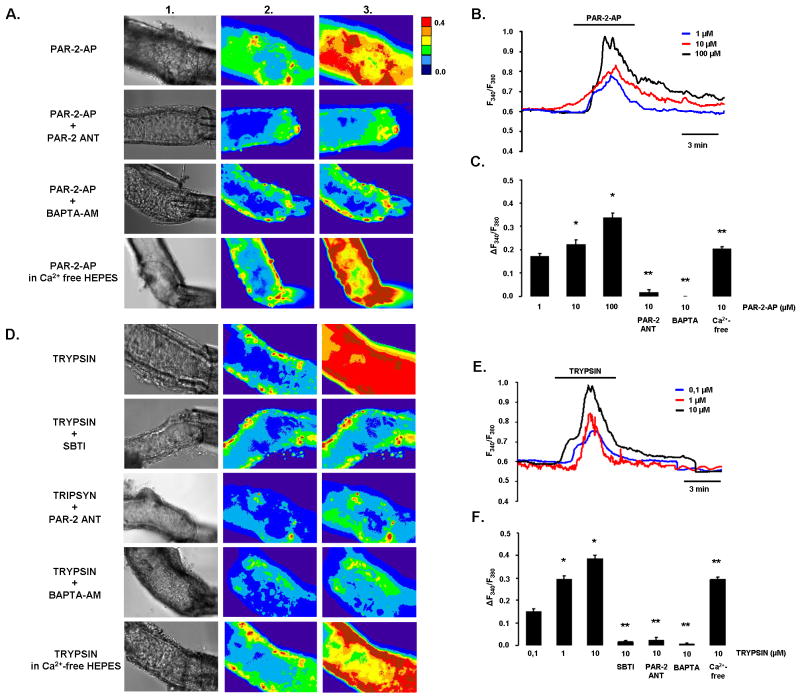

Luminal administration of PAR-2-AP and trypsin induces dose-dependent intracellular calcium signals

Since PAR-2 expression was detected only on the luminal membrane of intralobular duct cells, we used the microperfusion technique to see whether these receptors can be activated by PAR-2 agonists. First, the experiments were performed at pH 7.4 in order to understand the effects of trypsin and PAR-2 under quasi physiological conditions (Fig.2). The fluorescent images in Fig.2A clearly show that luminal administration of PAR-2 activating peptide (PAR-2-AP) increased [Ca2+]i in perfused pancreatic ducts. The [Ca2+]i response was dose-dependent, and consisted of a peak in [Ca2+]i which decayed in the continued presence of the agonist, possibly reflecting PAR-2 inactivation or depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Fig.2B). Pre-treatment of PDEC with 10μM PAR-2 antagonist (PAR-2-ANT) for 10min completely blocked the effects of 10μM PAR-2-AP on [Ca2+]i (Fig.2A,C). Removal of extracellular Ca2+ had no effect on the [Ca2+]i rise evoked by luminal administration of 10μM PAR-2-AP; however, pre-loading ducts with the calcium chelator BAPTA-AM at 40μM totally blocked the response (Fig.2A,C).

Figure 2. Effects of PAR-2-AP and trypsin on [Ca2+]i in microperfused guinea pig pancreatic ducts at pH 7.4.

A)Light (1) and fluorescent ratio images (2 and 3) of microperfused pancreatic ducts showing the effects of luminal administration of 10μM PAR-2-AP, 10μM PAR-2-ANT, or 40μM BAPTA-AM on [Ca2+]i. Images were taken before (1 and 2) and after (3) exposure of the ducts to PAR-2-AP or trypsin.B-C)Representative experimental traces and summary data of the changes in [Ca2+]i.D)The same protocol was used to evaluate the effects of trypsin. 5μM SBTI was used to inhibit trypsin activity.E-F)Representative experimental traces and summary data of the changes in [Ca2+]i. n=5 for all groups,*:P<0.05 vs. 1μM PAR-2-AP or 0.1μM trypsin, respectively. **:P<0.001 vs. 10μM PAR-2-AP or 10μM trypsin, respectively.

Trypsin also induced a dose-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation similar to that evoked by PAR-2-AP (Fig.2E,F). 5μM soybean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI), 10μM PAR-2-ANT and 40μM BAPTA-AM totally blocked the rise in [Ca2+]i (Fig.2D,F). These data show that trypsin activates PAR-2 on the luminal membrane of the duct cell which leads to release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and an elevation of [Ca2+]i.

Since the pH of pancreatic juice can vary between approximately 6.8 and 8.0 (23,24), we also checked the effects of trypsin and PAR-2-AP on [Ca2+]i at these pH values (supplementary Figs.1 and 2, respectively). The elevations of [Ca2+]i at pH6.8 and 8.0 were generally very similar to the changes observed at pH7.4. However, the [Ca2+]i rises evoked by 1μM PAR-2-AP and 0.1μM trypsin were significantly lower at pH6.8 compared to either pH7.4 or 8.0 (supplementary Fig.3).

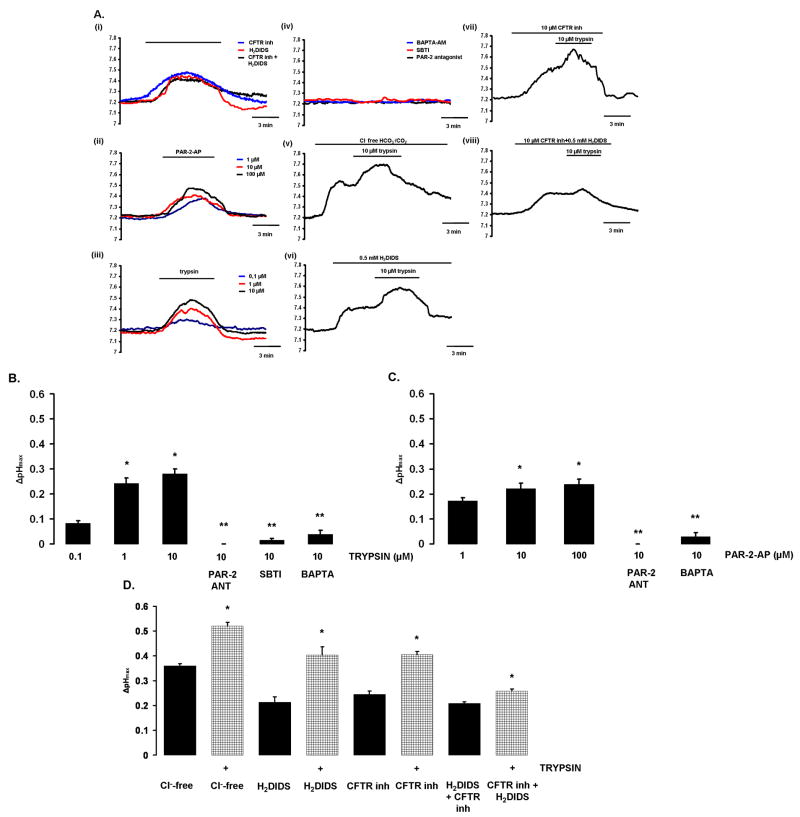

Luminal exposure to PAR-2-AP and trypsin evoke intracellular alkalosis in PDEC

Figure 3 shows pHi recordings from microperfused pancreatic ducts. Luminal application of the CFTR inhibitor-172 (CFTRinh-172,10μM) and the anion exchanger inhibitor H2DIDS (500μM) induced an intracellular alkalization in PDEC (Fig.3.Ai). These data indicate that when bicarbonate efflux across the luminal membrane of PDEC (i.e. bicarbonate secretion) is blocked an elevation of duct cell pHi occurs, presumably because the basolateral transporters continue to move bicarbonate ions into the duct cell. Note also that the rise in pHi evoked by the inhibitors is not sustained and begins to reverse before the inhibitors are withdrawn (Fig.3.Ai), which might be explained by the regulation of pHi by basolateral acid/base transporters.

Figure 3. A)Effects of PAR-2-AP and trypsin on pHi in microperfused guinea pig pancreatic ducts.

Representative pHi traces showing the effects of luminal administration of different agents in microperfused pancreatic ducts.i) 10μM CFTRinh-172 and/or 500μM H2DIDS caused alkalization of pHi.ii) PAR-2-AP and iii) trypsin induced a dose-dependent pHi elevation,iv) Preincubation of ductal cells with 10μM PAR-2-ANT or 5μM SBTI or 40μM BAPTA-AM totally blocked the alkalization caused by 10μM trypsin.v) Removal of luminal Cl- or vi) administration of H2DIDS (500μM) decreased, but did not totally abolish, the effects of 10μM trypsin on pHi. vii) Pretreatment with 10μM CFTRinh-172 also decreased the effects of trypsin (10μM) on pHi.viii) Simultaneous administration of H2DIDS and CFTRinh-172 strongly inhibited the effect of 10μM trypsin.B-C) Summary of the effects of PAR-2-AP and trypsin on pHi changes. ΔpHmax was calculated from the experiments shown in Panel A.D) Effects of Cl--free conditions. Cl--free conditions, H2DIDS, CFTRinh-172 and a combination of the inhibitors all induced an intracellular alkalosis. Trypsin further increased the alkalinisation of pHi although the effect was markedly reduced when both H2DIDS and CFTRinh-172 were present. n=4-5 for all groups.B)*:P<0.05 vs. 0.1μM trypsin;**:P<0.001 vs. 10μM trypsin,C)*:P<0.05 vs. 0.1μM PAR-2-AP;**:P<0.001 vs. 10μM PAR-2-AP,D)*:P<0.05 vs. the respective filled column.

Both luminal PAR-2-AP and trypsin induced a dose-dependent elevation of pHi (Fig.3A.ii,iii), suggesting that activation of PAR-2 inhibits bicarbonate efflux across the apical membrane of the duct cell. Pre-incubation of PDEC with either 10μM PAR-2-ANT or 5μM SBTI or 40μM BAPTA-AM for 30min totally blocked the effect of trypsin on pHi (Fig.3A.iv). The inhibitory effect of the calcium chelator, BAPTA-AM, suggests that the actions of trypsin and PAR-2-AP on pHi are mediated by the rise in [Ca2+]i that they evoke (Fig.2). Therefore, in this case, the transient nature of the pHi response may reflect the transient effect that PAR-2 activators have on [Ca2+]i (Fig.2B,E), as well as pHi regulation by basolateral acid/base transporters.

Next we tested the effects of trypsin on pHi in Cl--free conditions and during pharmacological inhibition of the luminal anion exchangers and/or CFTR (Fig.3.Av-viii). Luminal Cl--free conditions increased the pHi of PDEC presumably by driving HCO3- influx on the apical anion exchangers (Fig.3A.v). Note that luminal administration of trypsin further elevated pHi in Cl- free conditions (Fig.3A.v), and also in the presence of H2DIDS (Fig.3A.vi) and CFTRinh-127 (Fig.3A.vii). However, pre-treatment of ducts with a combination of H2DIDS and CFTRinh-172 markedly reduced the effect of trypsin on pHi (Fig.3A.viii).

Figure 3B-D is a summary of the pHi experiments. Trypsin (Fig.3B) and PAR-2-AP (Fig.3C) both induced statistically significant, dose-dependent, rises in pHi and these effects were blocked by PAR-2-ANT, SBTI and BAPTA-AM. Exposure of the ducts to luminal Cl- free conditions, H2DIDS, CFTRinh-172 or a combination of the inhibitors also induced an intracellular alkalosis (Fig.3D). Also shown in Fig.3D is the additional, statistically significant, rise in pHi caused by trypsin in ducts exposed to Cl--free conditions and the individual inhibitors. However, when ducts were exposed to both CFTRinh-172 and H2DIDS simultaneously, the effect of trypsin on pHi was markedly reduced although it remained statistically significant (Fig.3D). We interpret these results as indicating that trypsin inhibits both Cl- dependent (i.e. anion exchanger mediated; revealed when CFTR is blocked by CFTRinh-172) and Cl- independent (i.e. CFTR mediated; revealed in Cl--free conditions and when the luminal exchangers are blocked by H2DIDS) bicarbonate secretory mechanisms in PDEC. Reduced bicarbonate secretion will lead to a decrease in intraductal pH.

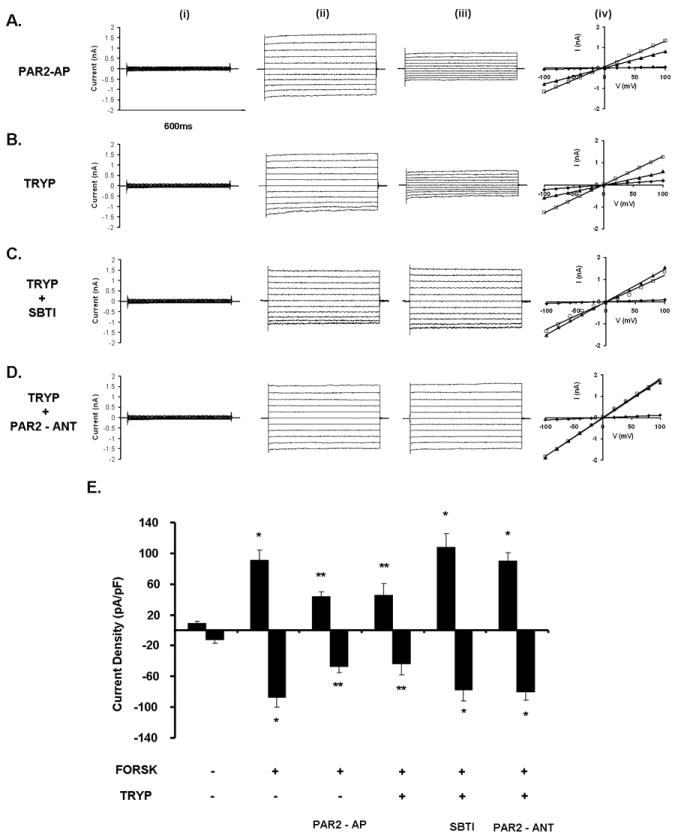

Trypsin and PAR-2-AP inhibit CFTR

Exposure of guinea pig PDEC to 5μM forskolin, which elevates intracellular cyclic AMP, increased basal whole cell currents (Fig.4A-D.i) from 8.9±2.3 pA/pF to 91.2±13.5 pA/pF (Fig.4A-D.ii) at +60 mV in 78% of cells (38/49). The forskolin-activated currents were time- and voltage-independent, with a near linear I/V relationship and a reversal potential of -5.15±1.12 mV (Fig.4A-D.iv). These biophysical characteristics indicate that the currents are carried by CFTR.

Figure 4. Effects of trypsin and PAR-2-AP on CFTR Cl- currents of guinea pig pancreatic duct cells.

Representative fast whole cell current recordings from PDEC.A-D) i) unstimulated currents, ii) currents after stimulation with 5μM forskolin, and iii) currents following 3min exposure to A) 10μM PAR-2-AP,B) 10μM trypsin,C) 10μM trypsin/5μM SBTI and D) 10μM trypsin/10μM PAR-2-ANT.iv) I/V relationships. Diamonds represent unstimulated currents, squares represent forskolin-stimulated currents and triangles represent forskolin-stimulated currents in the presence of the tested agents (see above).E) Summary of the current density (pA/pF) data obtained from A-D measured at Erev±60mV. Exposing PDEC to either PAR-2-AP or trypsin blocked the forskolin-stimulated CFTR Cl- currents, while administration of SBTI or PAR-2-ANT prevented the inhibitory effect of trypsin.n=6 for all groups.*:P<0.05 vs. the unstimulated cells,**:P<0.05 vs. forskolin

Exposure of PDEC to 10μM trypsin did not affect the basal currents; however, administration of either 10μM PAR-2-AP (Fig.4A.iii) or 10μM trypsin (Fig.4B.iii) inhibited forskolin-stimulated CFTR currents by 51.7±10.5 % and 57.4±4.0 %, respectively. In both cases, the inhibition was voltage-independent and irreversible. Pretreatment with either SBTI (10μM;Fig.4C.iii) or PAR-2-ANT (10μM;Fig.4D.iii) completely prevented the inhibitory effect of trypsin on the forskolin-stimulated CFTR currents. Fig.4E is a summary of these data which suggest that trypsin inhibits CFTR Cl- currents by activation of PAR-2.

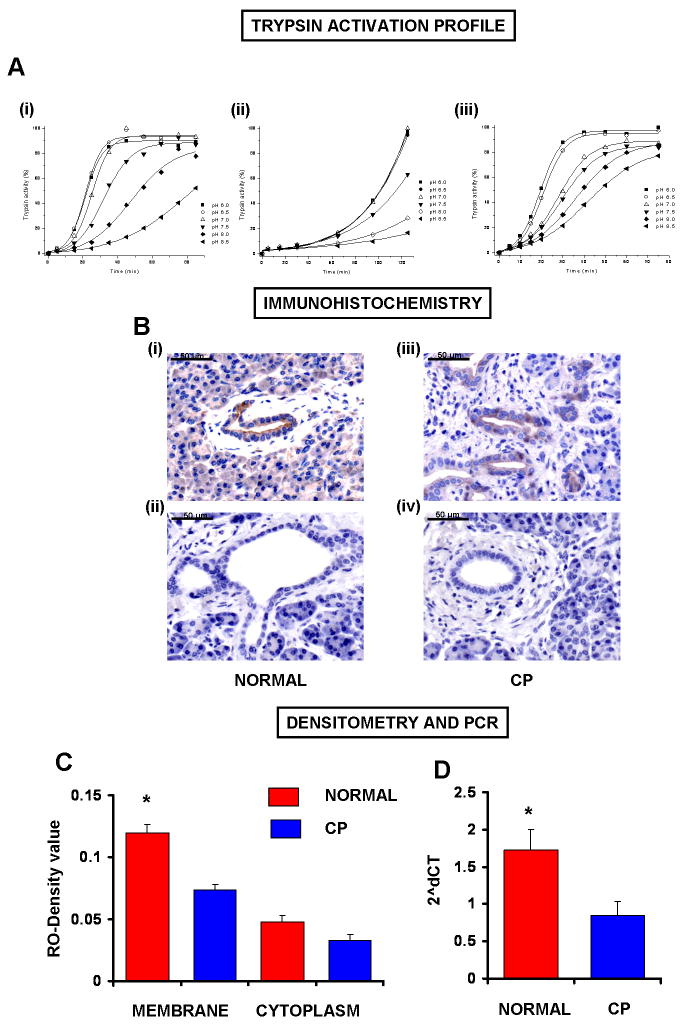

Autoactivation of trypsinogen is pH dependent

Trypsinogen can undergo autocatalytic activation during which trace amounts of trypsin are generated, which, in turn, can further activate trypsinogen in a self-amplifying reaction. Human trypsinogens are particularly prone to autoactivation and mutations that facilitate autoactivation are associated with hereditary pancreatitis. To assess the effect of a decrease in intraductal pH (caused by reduced bicarbonate secretion) on trypsinogen activation, we measured autoactivation of human cationic trypsinogen in vitro at pH values ranging from 6.0 to 8.5 using a mixture of various buffers. As shown in Fig.5A, the rate at which cationic trypsinogen autoactivates was markedly increased as the pH was reduced from 8.5 to 7.0 when the buffer solution contained 1mM CaCl2 and no NaCl. However, a further reduction in pH, from 7.0 to 6.0, had little effect (Fig.5A.i).

Figure 5. The effects of pH on trypsinogen activation and analyses of PAR-2 expression in human pancreatic samples.

The autoactivation of human cationic trypsinogen was determined in vitro at pH values ranging from 6.0 to 8.5.A.i) Trypsinogen at 2μM concentration was incubated with 40nM trypsin at 37°C in 0.1M Tris+HEPES+MES buffer mixture containing 1mM CaCl2.ii) The same protocol was used in high (100mM) NaCl buffer solution. Autoactivation of cationic trypsinogen significantly increased as the pH was reduced from 8.5 to 6.0.iii) The same protocol was used in low (0.1mM) Ca2+-buffered solution buffer solution.B.i-iv) PAR-2 expression.i) Representative section of normal human pancreas.ii) No primary antiserum.iii) Representative section of human pancreas from a patient suffering from chronic pancreatitis (CP).iv) No primary antiserum.C) Relative optical density.n=15,*:P<.05 vs. CP membrane.D) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of PAR-2 mRNA expression of human pancreas. Data are given in 2ˆdCT.n=15,*:P<0.05 vs. CP.

To rule out that the differences observed in autoactivation were due to the different ionic strengths of the buffers used, we repeated the experiments in the presence of a higher concentration of sodium (100mM NaCl,Fig.5A.ii) or lower concentration of calcium (0.1mM CaCl2,Fig.5A.iii). Although the overall autoactivation rates were much slower in the presence of NaCl, the pH profile of autoactivation was essentially identical to that observed in the absence of added salt (Fig.5A.ii). Also, pH dependent changes in the autoactivation of trypsinogen were still detectable when the experiments were performed using a low calcium buffer (Fig.5A.iii).

PAR-2 is down-regulated in patients suffering from chronic pancreatitis

It has been documented that there is activated trypsin in the pancreatic ductal lumen in chronic pancreatitis in humans25-28. If trypsin activity is elevated in the duct lumen, PAR-2 down-regulation should occur, which could be due either: (i) to changes in PAR-2 mRNA transcription and/or (ii) due to receptor internalization and translocation to the cytoplasm. Our data show a marked reduction in membranous PAR-2 protein level, but no significant changes in cytoplasmic PAR-2 protein in CP (Fig.5B.i-iv,C). Furthermore, PAR-2 mRNA level was markedly reduced in chronic pancreatitis (Fig.5D), suggesting that reduced PAR-2 mRNA transcription may cause PAR-2 down-regulation in CP.

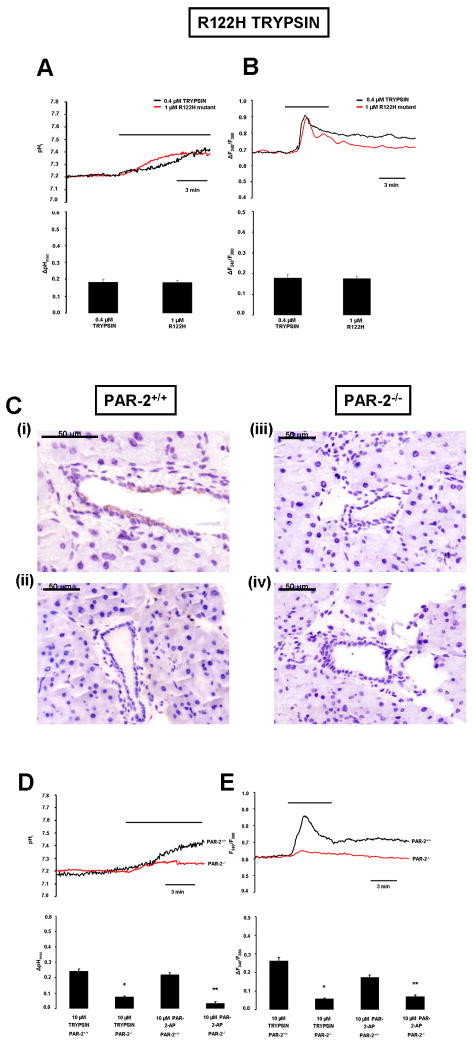

Luminal exposure to R122H mutant cationic trypsin induces elevation of intracellular calcium concentration and evokes alkalosis in PDEC

It has been demonstrated that mutations in cationic trypsinogen increase the risk of chronic pancreatitis, most likely because of the enhanced autoactivativation exhibited by the mutant trypsinogens29. Here we tested whether the commonest mutation in cationic trypsin, R122H, affected the protease’s ability to interact with PAR-2. Figure 6A-B shows that 1μm of R122H cationic trypsin causes comparable changes in pHi and [Ca2+]i to 0.4μM wild type trypsin, suggesting that a trypsin mediated inhibition of bicarbonate secretion could play a role in the pathogenesis of hereditary as well as chronic pancreatitis.

Figure 6. Experiments using R122H human mutant cationic trypsin and PAR-2-/- mice.

Representative A) pHi and B) [Ca2+]i. measurements using luminal administration of normal and R122H mutant cationic trypsin in microperfused guinea pig pancreatic ducts. n=5 for all experiments.C.i-iv) PAR-2 expressing cells were visualized by immunohistochemistry as described in Fig.1.i) Representative section of the pancreas removed from PAR-2+/+ mice.ii) Section without primary antiserum.iii) Pancreas removed from PAR-2-/- mice.iv) Section without primary antiserum.D) pHi and E) [Ca2+]i. measurements using luminal administration of trypsin in microperfused pancreatic ducts isolated from PAR-2 knock-out (red curve) and PAR-2 wild-type mice (black curve). n=5 for all experiments,*:P<0.05 vs. 10μM trypsin PAR-2+/+,**:P<0.05 vs. 10μM PAR-2-AP PAR-2+/+.

Activation of PAR-2 is diminished in PAR-2-/- mice

Finally, we investigated the effects of both PAR-2-AP and trypsin on PDEC isolated from PAR-2+/+ and PAR-2-/- mice (Fig.6C-E). First we confirmed using immunohistochemistry that PAR-2+/+ mice do, whereas PAR-2-/- mice do not, express PAR-2 in their PEDC (Fig.6C.i,iii). Accordingly, our functional data clearly show that the pHi and [Ca2+]i responses to luminal administration of either trypsin or PAR-2-AP were markedly diminished in PAR-2-/- PDEC (Fig.6D-E).

DISCUSSION

The human pancreatic ductal epithelium secretes 1-2L of alkaline fluid every 24 hours that may contain up to 140mM NaHCO312,13. The physiological function of this alkaline secretion is to wash digestive enzymes down the ductal tree and into the duodenum, and to neutralise acidic chyme entering the duodenum from the stomach. There are important lines of evidence supporting the idea that pancreatic ducts play a role in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis:i) ductal fluid and bicarbonate secretion are compromised in acute and chronic pancreatitis30,31, ii) one of the main endpoints of chronic pancreatitis is the destruction of the ductal system32,33, iii) mutations in CFTR may increase the risk of pancreatitis30,31,34-36, and iv) etiological factors for pancreatitis, such as bile acids or ethanol in high concentration, inhibit pancreatic ductal bicarbonate secretion37-39. Despite the above mentioned data, the role of PDEC in the development of pancreatitis has received relatively little attention40.

There are important species differences regarding the localization of PAR-2 in pancreatic ducts and in the effect of its activation on bicarbonate secretion. For example, CAPAN-1 cells10 and dog PDEC9 express PAR-2 only on the basolateral membrane, whereas bovine PDEC express PAR-2 on the luminal membrane11. Therefore, one of our first aims was to determine which animal model best mimics human PAR-2 expression and thus would be the best for studying the effects of trypsin on PDEC function. Our results showed that in the human pancreas PAR-2 is localized to the luminal membrane of small proximal pancreatic ducts, which are probably the major site of bicarbonate and fluid secretion. Since CAPAN-1 cells and dog PDEC express PAR-2 only on the basolateral membrane, they do not mimic the human situation. Rats or mice are also not good models for the human gland because they secrete only 70-80mM bicarbonate41,42. However, the guinea pig pancreas secretes ~140mM bicarbonate, as does the human gland, and the regulation of bicarbonate secretion is similar in both species41,42. Since PAR-2 expression in the guinea pig pancreas was localized to the luminal membrane of duct cells, we performed our experiments on isolated guinea pig ducts.

First we characterized the effects of PAR-2 activation by trypsin and PAR-2-AP on PDEC. Previously, it has been shown that activation of the G-protein-coupled PAR-2 by proteinases requires proteolytic cleavage of the receptor, which is followed by an elevation of [Ca2+]i43-45. As expected, luminal trypsin and PAR2-AP caused a dose-dependent elevation of [Ca2+]i in guinea pig ducts. Importantly, the trypsin inhibitor SBTI, PAR-2-ANT and the intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-AM all completely blocked the elevation of [Ca2+]i, whereas removal of extracellular Ca2+ had no effect. Acidosis (pH6.8) also slightly reduced the changes in [Ca2+]i evoked by trypsin, most probably due to reduced cleavage activity of trypsin at an acidic pH. Next we characterized the effects of PAR-2 activation on pHi. Luminal application of trypsin and PAR-2-AP both caused a dose-dependent intracellular alkalosis in PDEC. This alkalosis is most likely explained either by a reduction in the rate of bicarbonate efflux (i.e. secretion) across the apical membrane of PDEC or by an increase in the rate of bicarbonate influx at the basolateral side of the cell. We favour the former explanation as luminal application of the anion exchange inhibitor, H2DIDS, or the CFTR inhibitor, CFTRinh-172, produced a similar intracellular alkalization22,46. Thus PAR-2 activation inhibits bicarbonate secretion in PDEC by inhibiting SLC26 anion exchangers and CFTR Cl- channels expressed on the apical membrane of the duct cell. In similarity with the [Ca2+]i signals, the effect of PAR-2 activation on pHi was blocked by SBTI, PAR-2-ANT and BAPTA-AM; the action of BAPTA-AM suggesting that the inhibition of bicarbonate secretion follows from the rise in [Ca2+]i. Interestingly, an elevation of [Ca2+]i is crucial for both stimulatory (e.g. acetylcholine13, low concentrations of bile acids39 and ethanol38) and inhibitory pathways (e.g. basolateral ATP, arginine vasopressin and high concentrations of ethanol) that control bicarbonate secretion by PDEC. Such marked differences in the outcome of [Ca2+]i signals in PDEC probably reflect differences in the source of Ca2+ and/or in the intracellular compartmentalisation of [Ca2+]i signals generated by different secretory agonists and antagonists.

Remarkably, trypsin was still able to evoke an elevation of pHi when Cl- was removed from the duct lumen and when PDEC were pre-treated with H2DIDS, conditions that should inhibit bicarbonate efflux on the exchanger. These results suggested the involvement of CFTR, the only other known bicarbonate efflux pathway on the apical membrane, in the inhibitory effect of trypsin. This hypothesis was confirmed by patch clamp experiments in which trypsin decreased CFTR whole cell currents in isolated guinea pig PDEC by 50-60%. Finally, the fact that the trypsin-induced alkalinisation was completely blocked by a combination of CFTRinh-172 and H2DIDS confirms the involvement of both CFTR and SLC26 anion exchangers. Our conclusion from these pHi and patch clamp data is that PAR-2 activation inhibits both the SLC26 anion exchanger (probably SLC26A6 (PAT-1)47 as SLC26A3 (DRA) is only weakly inhibited by disulfonic stilbenes47,48) and CFTR Cl- channels expressed on the apical membrane of the duct cell.

The pH of pancreatic juice (and therefore the luminal pH (pHL) in the duct) can vary between approximately 6.8 and 8.0. It has recently been shown that protons co-released during exocytosis cause significant acidosis (up to 1pH unit) in the lumen of the acini23. However, Ishiguro et al.49 have clearly shown that the pHL in pancreatic ducts is dependent on the level of bicarbonate secretion. pHL can be elevated from 7.2 to 8.5 by stimulation with secretin or forskolin and this effect was strictly dependent on the presence of bicarbonate24,49,50. Also, inhibition of ductal bicarbonate secretion with H2DIDS can decrease the pHL to below 8.049. In view of these results, we tested whether trypsinogen autoactivation was affected by pH over the range 6.0 to 8.5. Autoactivation of trypsinogen was relatively slow at pH 8.5, but decreasing the pH from 8.5 to 7 progressively stimulated autoactivation. These results suggest that under physiological conditions bicarbonate secretion by PDEC is not only important for elevating the pH in the duodenum, but also for keeping pancreatic enzymes in an inactive state in the ductal system of the gland.

Receptor down-regulation is a phenomenon that occurs in the continued presence of an agonist and leads to a reduction in the cell’s sensitivity to the agonist. Potentially, there are two mechanisms that could underlie receptor down-regulation of PAR-2: i) after proteolytic activation, the PAR-2 is internalized by a clathrin-mediated mechanism and then targeted to lysosomes45, and ii) if trypsin is present for a longer time in the lumen, PAR-2 may be down-regulated at the transcriptional level. In this study, we provide evidence that the second mechanism, transcriptional down-regulation, explains the reduced expression of PAR-2 seen in chronic pancreatitis.

Conflicting data can be found in the literature concerning the role of PAR-2 in acute pancreatitis. Singh et al.7 showed that in secretagogue-induced experimental pancreatitis, PAR-2 deletion is associated with a more severe pancreatitis. Although Laukkarinen et al.17 confirmed these results in cerulein-induced pancreatitis, they also clearly showed that in taurocholate-induced pancreatitis, PAR-2 deletion markedly reduced the severity of the disease. There is no evidence to suggest that clinical pancreatitis is evoked by supramaximal secretagoge stimulation; however, the taurocholate-induced pancreatitis model may mimic the clinical situation. Therefore, Laukkarinen et al.17 speculated that PAR-2 activation promotes the worsening of clinical pancreatitis and our data are consistent with that hypothesis.

Besides the clear pathophysiological role of the trypsin-PAR-2 interaction in chronic pancreatitis, there is still a debate as to why PAR-2 are localized to the luminal membrane of PDEC in small ducts close to the acinar cells. What could the physiological role of this PAR-2 be? A number of agents have been shown to have dual effects on PDEC at different concentrations. For example, bile acids in low concentrations stimulate, but in high concentrations inhibit bicarbonate secretion39. The same applies to ethanol38. Under physiological conditions, trypsin inhibitors are co-released from acinar cells with trypsinogen and should block the activity of any trypsin that is generated spontaneously. Therefore, only very small amounts of active trypsin, if any, will be present in the duct lumen under normal conditions. However, there remains a possibility that very small amounts of active trypsin (i.e. concentrations below 0.1μM that would not cause a [Ca2+]i elevation or pH change) could bind to PAR-2 on the luminal membrane of the ducts and augment other stimulatory mechanisms so as to enhance flushing of digestive enzymes down the ductal tree.

In conclusion, we suggest for the first time that one of the physiological roles of bicarbonate secretion by PDEC is to curtail trypsinogen autoactivation within the pancreatic ductal system. However, if trypsin is present in the duct lumen (as may occur during the early stages of pancreatitis due to leakage from acinar cells), PAR-2 on the duct cell will be activated leading to Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. This causes inhibition of the luminal anion exchangers and CFTR Cl- channels reducing bicarbonate secretion by the duct cell. The fall in bicarbonate secretion will increase the transit time of zymogens down the duct tree and decrease pHL, both of which will promote the autoactivation of trypsinogen. The trypsin so formed will further inhibit bicarbonate transport leading to a vicious cycle generating further falls in pHL and enhanced trypsinogen activation, which will favour development of the pancreatitis (supplementary Fig.4). Finally, the R122H mutant cationic trypsin also elevated [Ca2+]i and pHi in duct cells, suggesting that this mechanism may be particularly important in hereditary pancreatitis in which the mutant trypsinogens more readily autoactivate29.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund to V.V., Z.R. and P.H. (PD78087, K78311 and NNF 78851), Bolyai Postdoctoral Fellowships to P.H. and Z.R. (00334/08/5, 00174/10/5) awarded by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, an European Pancreatic Club Travel Grant, NKTH grants (TÁMOP-4.2.2-08/1/2008-0002 and 0013, TÁMOP 4.2.1.B-09/1/KONV), NIH grant DK058088 (to M. S.-T.) and scholarships from the Rosztoczy Foundation (to A.G. and A.S.).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- BAPTA-AM

1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl- channel

- CFTRinh-172

CFTR inhibitor-172

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- DRA

Down-regulated in adenoma

- H2DIDS

dihydro-4,4’-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2’-disulfonic acid

- PAR-2

proteinase-activated receptor-2

- PAR-2+/+

PAR-2 wild-type

- PAR-2-/-

PAR-2 knock-out

- PAR-2-AP

PAR-2 activating peptide

- PAR-2-ANT

PAR-2 antagonist

- PAT-1

Putative anion transporter 1

- PDEC

pancreatic ductal epithelial cells

- pHi

intracellular pH

- RT-PCR

real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SBTI

soybean trypsin inhibitor

- SLC26

solute carrier family 26

Footnotes

Katalin Borka and Anna Korompay performed immunohistochemical and PCR reactions. Viktória Venglovecz, Linda Judák, Mike A. Gray and Barry E. Argent played parts in electrophysiology. Petra Pallagi, Béla Ózsvári, Tamás Takács and Zoltán Rakonczay and József Maléth contributed to the fluorescence measurements. Andrea Geisz, Andrea Schnúr, and Miklós Sahin-Tóth measured trypsinogen autoactivation. Julia Mayerle and Markus M. Lerch and Tibor Wittmann were involved in the PAR-2-/- experiments. Péter Hegyi was the supervisor of the study. The manuscript was drafted by Péter Hegyi, Zoltán Rakonczay and Barry E. Argent.

Conflict of Interest: None to declare

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Petersen OH. Physiology of acinar cell secretion. In: H B, editor. The Pancreas. second ed. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing; 2008. pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lerch MM, Gorelick FS. Early trypsinogen activation in acute pancreatitis. Med Clin North Am. 2000;84:549–63. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thrower EC, Gorelick FS, Husain SZ. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of pancreatic injury. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;84:549–63. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833d119e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geokas MC, Rinderknecht H. Free proteolytic enzymes in pancreatic juice of patients with acute pancreatitis. Am J Dig Dis. 1974;19:591–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01073012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renner IG, Rinderknecht H, Douglas AP. Profiles of pure pancreatic secretions in patients with acute pancreatitis: the possible role of proteolytic enzymes in pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:1090–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Withcomb D, Beger H. Definitions of pancreatic diseases and their complications. In: H B, editor. The Pancreas. second ed. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing; 2008. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh VP, Bhagat L, Navina S, Sharif R, Dawra RK, Saluja AK. Protease-activated receptor-2 protects against pancreatitis by stimulating exocrine secretion. Gut. 2007;56:958–64. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.094268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawabata A, Kuroda R, Nishida M, Nagata N, Sakaguchi Y, Kawao N, Nishikawa H, Arizono N, Kawai K. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) in the pancreas and parotid gland: Immunolocalization and involvement of nitric oxide in the evoked amylase secretion. Life Sci. 2002;71:2435–46. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen TD, Moody MW, Steinhoff M, Okolo C, Koh DS, Bunnett NW. Trypsin activates pancreatic duct epithelial cell ion channels through proteinase activated receptor-2. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:261–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Namkung W, Lee JA, Ahn W, Han W, Kwon SW, Ahn DS, Kim KH, Lee MG. Ca2+ activates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator- and Cl--dependent HCO3- transport in pancreatic duct cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:200–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez C, Regan JP, Merianos D, Bass BL. Protease-activated receptor-2 regulates bicarbonate secretion by pancreatic duct cells in vitro. Surgery. 2004;136:669–76. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M, Muallem S. Physiology of duct cell secretion. In: H B, editor. The Pancreas. second ed. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing; 2008. pp. 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Argent BE. Cell Physiology of Pancreatic Ducts. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 4. Vol. 2. San Diego: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 1376–1396. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hegyi P, Rakonczay Z, Jr, Farkas K, Venglovecz V, Ozsvari B, Seidler U, Gray MA, Argent BE. Controversies in the role of SLC26 anion exchangers in pancreatic ductal bicarbonate secretion. Pancreas. 2008;37:232–4. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318164f8ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishiguro H, Steward MC, Sohma Y, Kubota T, Kitagawa M, Kondo T, Case RM, Hayakawa T, Naruse S. Membrane potential and bicarbonate secretion in isolated interlobular ducts from guinea-pig pancreas. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:617–28. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohma Y, Gray MA, Imai Y, Argent BE. HCO3- transport in a mathematical model of the pancreatic ductal epithelium. J Membr Biol. 2000;176:77–100. doi: 10.1007/s00232001077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laukkarinen JM, Weiss ER, van Acker GJ, Steer ML, Perides G. Protease-activated receptor-2 exerts contrasting model-specific effects on acute experimental pancreatitis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20703–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801779200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawabata A, Matsunami M, Tsutsumi M, Ishiki T, Fukushima O, Sekiguchi F, Kawao N, Minami T, Kanke T, Saito N. Suppression of pancreatitis-related allodynia/hyperalgesia by proteinase-activated receptor-2 in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:54–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma A, Tao X, Gopal A, Ligon B, Andrade-Gordon P, Steer ML, Perides G. Protection against acute pancreatitis by activation of protease-activated receptor-2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G388–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00341.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Namkung W, Han W, Luo X, Muallem S, Cho KH, Kim KH, Lee MG. Protease-activated receptor 2 exerts local protection and mediates some systemic complications in acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1844–59. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Argent BE, Arkle S, Cullen MJ, Green R. Morphological, biochemical and secretory studies on rat pancreatic ducts maintained in tissue culture. Q J Exp Physiol. 1986;71:633–48. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1986.sp003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegyi P, Rakonczay Z, Jr, Tiszlavicz L, Varro A, Tóth A, Racz G, Varga G, Gray MA, Argent BE. Protein kinase C mediates the inhibitory effect of substance P on HCO3- secretion from guinea pig pancreatic ducts. Am J Physiol CellPhysiol. 2005;288:C1030–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00430.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Behrendorff N, Floetenmeyer M, Schwiening C, Thorn P. Protons released during pancreatic acinar cell secretion acidify the lumen and contribute to pancreatitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1711–20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishiguro H, Steward MC, Wilson RW, Case RM. Bicarbonate secretion in interlobular ducts from guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol. 1996;495(Pt 1):179–91. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kukor Z, Mayerle J, Kruger B, Tóth M, Steed PM, Halangk W, Lerch MM, Sahin-Tóth M. Presence of cathepsin B in the human pancreatic secretory pathway and its role in trypsinogen activation during hereditary pancreatitis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21389–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tympner F, Rosch W. Viscosity and trypsin activity of pure pancreatic juice in chronic pancreatitis. Acta Hepatogastroenterol (Stuttg) 1978;25:73–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fedail SS, Harvey RF, Salmon PR, Brown P, Read AE. Trypsin and lactoferrin levels in pure pancreatic juice in patients with pancreatic disease. Gut. 1979;20:983–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.20.11.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tympner F. Selectively aspirated pure pancreatic secretion. Viscosity, trypsin activity, protein concentration and lactoferrin content of pancreatic juice in chronic pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1981;28:169–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahin-Tóth M, Tóth M. Gain-of-function mutations associated with hereditary pancreatitis enhance autoactivation of human cationic trypsinogen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:286–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavestro GM, Zuppardo RA, Bertolini S, Sereni G, Frulloni L, Okolicsanyi S, Calzolari C, Singh SK, Sianesi M, Del Rio P, Leandro G, Franze A, Di Mario F. Connections between genetics and clinical data: Role of MCP-1, CFTR, and SPINK-1 in the setting of acute, acute recurrent, and chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:199–206. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hegyi P, Rakonczay Z. Insufficiency of electrolyte and fluid secretion by pancreatic ductal cells lead to increase patients risk to pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2119–20. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kloppel G, Luttges J, Sipos B, Capelli P, Zamboni G. Autoimmune pancreatitis: pathological findings. Jop. 2005;6:97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ectors N, Maillet B, Aerts R, Geboes K, Donner A, Borchard F, Lankisch P, Stolte M, Luttges J, Kremer B, Kloppel G. Non-alcoholic duct destructive chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1997;41:263–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hegyi P, Pandol S, Venglovecz V, Rakonczay Z. The acinar-ductal tango in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2011;60:544–52. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.218461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nousia-Arvanitakis S. Cystic fibrosis and the pancreas:recent scientific advances. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:138–42. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199909000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss FU, Simon P, Bogdanova N, Shcheynikov N, Muallem S, Lerch MM. Functional characterisation of the CFTR mutations M348V and A1087P from patients with pancreatitis suggests functional interaction between CFTR monomers. Gut. 2009;58:733–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.167650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maleth J, Venglovecz V, Rázga Zs, Tiszlavicz L, Rakonczay Z, Hegyi P. The non-conjugated chenodeoxycholate induces severe mitochondrial damage and inhibits bicarbonate transport in pancreatic duct cells. Gut. 2011;60:136–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto A, Ishiguro H, Ko SB, Suzuki A, Wang Y, Hamada H, Mizuno N, Kitagawa M, Hayakawa T, Naruse S. Ethanol induces fluid hypersecretion from guinea-pig pancreatic duct cells. J Physiol. 2003;551:917–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.048827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venglovecz V, Rakonczay Z, Jr, Ozsvari B, Takacs T, Lonovics J, Varro A, Gray MA, Argent BE, Hegyi P. Effects of bile acids on pancreatic ductal bicarbonate secretion in guinea pig. Gut. 2008;57:1102–12. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.134361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee MG, Muallem S. Pancreatitis: the neglected duct. Gut. 2008;57:1037–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.150961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Padfield PJ, Garner A, Case RM. Patterns of pancreatic secretion in the anaesthetised guinea pig following stimulation with secretin, cholecystokinin octapeptide, or bombesin. Pancreas. 1989;4:204–9. doi: 10.1097/00006676-198904000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steward MC, Ishiguro H, Case RM. Mechanisms of bicarbonate secretion in the pancreatic duct. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:377–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.031103.153247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vergnolle N. Review article: proteinase-activated receptors-novel signals for gastrointestinal pathophysiology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:257–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohm SK, Khitin LM, Grady EF, Aponte G, Payan DG, Bunnett NW. Mechanisms of desensitization and resensitization of proteinase-activated receptor-2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22003–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoxie JA, Ahuja M, Belmonte E, Pizarro S, Parton R, Brass LF. Internalization and recycling of activated thrombin receptors. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13756–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stewart AK, Yamamoto A, Nakakuki M, Kondo T, Alper SL, Ishiguro H. Functional coupling of apical Cl-/HCO3- exchange with CFTR in stimulated HCO3- secretion by guinea pig interlobular pancreatic duct. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1307–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90697.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ko SB, Shcheynikov N, Choi JY, Luo X, Ishibashi K, Thomas PJ, Kim JY, Kim KH, Lee MG, Naruse S, Muallem S. A molecular mechanism for aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO3- transport in cystic fibrosis. Embo J. 2002;21:5662–72. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chernova MN, Jiang L, Shmukler BE, Schweinfest CW, Blanco P, Freedman SD, Stewart AK, Alper SL. Acute regulation of the SLC26A3 congenital chloride diarrhoea anion exchanger (DRA) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 2003;549:3–19. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ishiguro H, Naruse S, Steward MC, Kitagawa M, Ko SB, Hayakawa T, Case RM. Fluid secretion in interlobular ducts isolated from guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol. 1998;511(Pt 2):407–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.407bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishiguro H, Naruse S, Kitagawa M, Hayakawa T, Case RM, Steward MC. Luminal ATP stimulates fluid and HCO3- secretion in guinea-pig pancreatic duct. J Physiol. 1999;519(Pt 2):551–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0551m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.