Abstract

Study Objectives:

The atypical antipsychotic olanzapine is used effectively for treating symptoms of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Unwanted effects of olanzapine include slowing of the electroencephalogram (EEG) during wakefulness and increased circulating levels of leptin. The mechanisms underlying the desired and undesired effects of olanzapine are poorly understood. Sleep and wakefulness are modulated by acetylcholine (ACh) in the prefrontal cortex, and leptin alters cholinergic transmission. This study tested the hypothesis that olanzapine interacts with leptin to regulate ACh release in the prefrontal cortex.

Design:

Within/between subjects.

Setting:

University of Michigan.

Patients or Participants:

Adult male C57BL/6J (B6) mice (n = 33) and B6.V-Lepob (leptin-deficient) mice (n = 31).

Interventions:

Olanzapine was delivered to the prefrontal cortex by microdialysis. Leptin-replacement in leptin-deficient mice was achieved using subcutaneous micro-osmotic pumps.

Measurements and Results:

Olanzapine caused a concentration-dependent increase in ACh release in B6 and leptin-deficient mice. Olanzapine was 230-fold more potent in leptin-deficient than in B6 mice for increasing ACh release, yet olanzapine caused a 51% greater ACh increase in B6 than in leptin-deficient mice. Olanzapine had no effect on recovery time from general anesthesia. Olanzapine increased EEG power in the delta (0.5-4 Hz) range. Thus, olanzapine dissociated the normal coupling between increased cortical ACh release, increased behavioral arousal, and EEG activation. Leptin replacement significantly enhanced (75%) the olanzapine-induced increase in ACh release.

Conclusion:

Replacing leptin by systemic administration restored the olanzapine-induced enhancement of ACh release in the prefrontal cortex of leptin-deficient mouse.

Citation:

Wathen AB; West ES; Lydic R; Baghdoyan HA. Olanzapine causes a leptin-dependent increase in acetylcholine release in mouse prefrontal cortex. SLEEP 2012;35(3):315-323.

Keywords: Atypical antipsychotics, C57BL/6J mouse, B6.V-Lepob mouse

INTRODUCTION

Olanzapine is a second generation, or atypical, antipsychotic that is widely and effectively used for treating symptoms of schizophrenia1 and bipolar disorder.2,3 The first generation (or typical) antipsychotic, chlorpromazine, was introduced for the treatment of schizophrenia in the 1950s. Chlorpromazine and related phenothiazines are effective for treating the positive symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g., delusions, hallucinations, agitation, disordered thoughts) but cause severe extrapyramidal effects that limit usefulness.4 Clozapine was introduced as an antipsychotic in Europe in the early 1970s and was referred to as “atypical” because it does not cause extrapyramidal symptoms.5 The effectiveness of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia combined with its lack of adverse extrapyramidal effects spurred the development of additional second-generation antipsychotics, such as olanzapine. Unwanted effects of olanzapine include significant weight gain and metabolic syndrome.6,7 Although olanzapine improves sleep in patients with schizophrenia,8,9 additional negative effects are increased EEG slow wave activity during wakefulness10 and behavioral somnolence.11 Olanzapine also increases circulating leptin levels in patients with schizophrenia.12

Leptin is a peptide synthesized by adipocytes and normally functions as a satiety factor.13 B6.V-Lepob (leptin-deficient) mice do not synthesize leptin as a result of a spontaneous nonsense mutation in one gene.14,15 Leptin-deficient mice are obese, have disrupted sleep,16 and display respiratory depression during sleep.17 Compared to the C57BL/6J (B6) parent line, leptin-deficient mice exhibit blunted cholinergic enhancement of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep18 and antinociception.19 Replacement of leptin in leptin-deficient mice restores cholinergically induced antinociception19 and stimulates breathing.17 Therefore, these two mouse lines offer a unique resource for investigating the interaction between leptin and acetylcholine (ACh) in brain regions regulating sleep.

Patients with a lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia show a significant increase in the number of cholinergic neurons in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus of the brainstem.20,21 These neurons project to the substantia nigra, and excessive cholinergic stimulation of the substantia nigra leading to increased dopaminergic tone in the striatum has been postulated to contribute to some symptoms of schizophrenia.22 ACh increases dopamine release in the striatum by activating nicotinic receptors.23 Abnormal regulation of cholinergic afferents to the cortex also has been suggested as a possible mechanism accounting for some symptoms of schizophrenia, such as disordered thinking and cognitive impairments.24

In the prefrontal cortex of B6 mouse, muscarinic cholinergic receptors modulate ACh release,25 EEG slow waves, and EEG spindles.26,27 Enhancing cholinergic transmission in the prefrontal cortex also promotes behavioral arousal.28,29 The present study tested the hypothesis that olanzapine differentially increases ACh release in the prefrontal cortex of B6 and leptin-deficient mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Surgical Preparation for Microdialysis

The University of Michigan Animal Use and Care Committee approved all procedures that used animals, and experiments were conducted according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.30 Adult male B6 (n = 33) and leptin-deficient (n = 31) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (2%; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) in oxygen (100%) and placed in a David Kopf (Tujunga, CA) model 962 stereotaxic frame with a model 921 mouse adapter and model 907 mouse anesthesia mask. The concentration of isoflurane delivered to the mask was monitored continuously using a Datex-Ohmeda (Louisville, CO) Cardiocap/5 instrument. Core body temperature was monitored and maintained by use of a water-filled pad and a pump to recirculate warm (37°C) water (Gaymar Industries, Orchard Park, NY). A midline scalp incision and craniotomy provided access to the brain. A CMA/7 dialysis probe (1.0 mm length × 0.24 mm diameter with 6 kDa cutoff, CMA Microdialysis, North Chelmsford, MA) was aimed unilaterally for the frontal association area using the stereotaxic coordinates 3.0 mm anterior, 1.6 mm lateral, and 1.8 mm ventral to bregma.31 The frontal association area is the mouse homologue of the prefrontal cortex.32,33 Microdialysis probes were perfused continuously (2 μL/min) with Ringer's solution (147 mM NaCl, 2.4 mM CaCl2, 4 mM KCl) containing neostigmine (10 μM) and dimethyl sulfoxide (1%). The concentration of delivered isoflurane was decreased to 1.3% and 1.5% for B6 and leptin-deficient mice, respectively, and held constant for the duration of the experiment.

In Vivo Microdialysis

These experiments were designed to determine whether dialysis administration of olanzapine to the prefrontal cortex of B6 and leptin-deficient mouse differentially alters local ACh release and anesthesia recovery time. Collection of dialysis samples began 40 min after insertion of the microdialysis probe into the cortex. The dialysis probe was perfused with Ringer's solution (control) followed by Ringer's solution containing olanzapine (Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc., North York, ON, Canada). Only one concentration of olanzapine (0, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, or 100 μM) was tested per experiment, and each mouse was used for only one experiment. Dialysis samples (25 μL each) were obtained sequentially every 12.5 min for 125 min, yielding 5 replicates during dialysis with Ringer's solution and 5 measures during dialysis with olanzapine. ACh release (pmol/12.5 min) was quantified by injecting the dialysate into a high-performance liquid chromatography system with electrochemical detection (Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN), as previously described.25,29,34,35 After acquiring the final microdialysis sample, the dialysis probe was removed from the brain, the skin incision was closed, and delivery of isoflurane was discontinued.

The duration of exposure to isoflurane, measured as the time (min) from the onset of anesthetic induction to the cessation of isoflurane delivery, was recorded for each experiment. To quantify anesthesia recovery time, mice were placed in dorsal recumbency immediately following cessation of isoflurane delivery and kept warm using a heat lamp. The time (min) needed for the mice to right themselves was recorded. Resumption of righting response is a widely used index for time to recovery of wakefulness following general anesthesia.29,34–38

Before and after each experiment, the percent of ACh recovered by the dialysis membrane was determined in vitro by placing the probe into a known concentration of ACh and collecting 5 samples. Pre- and post-experiment recovery of ACh was compared by t-test, and only those experiments with probe recoveries that did not significantly change were included in the final data analysis. This procedure ensured that changes in ACh release measured during an experiment were not due to changes in the dialysis membrane. Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) recovery of ACh for the dialysis probes used in these studies was 4.7% ± 0.08%.

EEG Recording and Analysis

The left and right prefrontal cortical regions of B6 mouse share reciprocal connections.27 This finding encouraged additional experiments using B6 mice to determine whether dialysis delivery of olanzapine to one side of the prefrontal cortex alters EEG power in the contralateral prefrontal cortex. A dialysis probe was aimed for the prefrontal cortex as described above. Two 0.13-mm diameter stainless steel wire (California Fine Wire, Grover Beach, CA) electrodes were placed under the skull above the contralateral cortex 1.5 mm lateral to the midline at 2.8 and 2.4 mm anterior to bregma.31 Recordings of the cortical EEG were made during dialysis with Ringer's solution (control; 62.5 min) followed by dialysis with olanzapine (30 μM; 62.5 min).

The EEG signal was amplified and filtered between 0.3 and 30 Hz using a Grass (West Warwick, RI) Model P511K amplifier. The signal was then captured digitally with a sampling rate of 128 Hz using a Micro 1401 mk-II data acquisition unit and Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, England). Fast Fourier transform (FFT) analyses were conducted on 10-s bins ranging between 0.5 Hz and 25.0 Hz in 0.5-Hz increments in order to determine EEG power (V2). Bins were chosen for analysis in a systematic manner, with one bin chosen every 250 s, yielding 3 EEG power measures for each microdialysis sample.

Leptin Replacement

A third set of experiments was performed to investigate whether leptin replacement in leptin-deficient mice restores the olanzapine-induced increase in prefrontal cortex ACh release to levels observed in B6 mice. On the first day of these experiments, leptin-deficient mice were weighed, anesthetized with isoflurane, and implanted with a subcutaneous model 1007D Alzet micro-osmotic pump (Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA). These pumps delivered mouse recombinant leptin continuously at a rate of 15 μL/day. On day 7, mice were weighed and anesthetized with isoflurane. A CMA/7 microdialysis probe was aimed for the prefrontal cortex, and a microdialysis experiment was performed as described above. The probe was perfused continuously with Ringer's solution, followed by Ringer's solution containing olanzapine (100 μM). Upon completion of the dialysis experiment, the micro-osmotic pump was removed and a blood sample was collected via tail snip. The blood serum was separated and frozen. An enzyme linked immunosorbent assay kit (Catalog #90030, Crystal Chem Inc., Downers Grove, IL) was used to quantify leptin levels in serum samples obtained from B6, leptin-deficient, and leptin-replaced mice.

Histological Confirmation of Dialysis Probe Placement in the Prefrontal Cortex

Seven days after the microdialysis experiment, each mouse was deeply anesthetized and decapitated. Brains were removed immediately and rapidly frozen. Serial coronal sections (40 μm thick) through the prefrontal cortex were slide mounted, dried, fixed with hot (80°C) paraformaldehyde vapor, and stained with cresyl violet. The locations of the microdialysis sites were identified by comparing stained sections with a stereotaxic atlas of the mouse brain.31 Results from individual experiments were included in the group data set only if ≥ 67% of the dialysis membrane was confirmed to be within the prefrontal cortex.

Statistical Analyses

For each experiment, ACh release was expressed as percent of control (dialysis with Ringer's solution) in order to evaluate whether ACh release in the prefrontal cortex varied as a function of the concentration of olanzapine and mouse line. The effects of olanzapine concentration and mouse line on the dependent measures of ACh release and anesthesia recovery time were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc t-tests with Bonferroni correction. The effects of the concentration of olanzapine on ACh release also were analyzed using nonlinear regression to calculate the concentration of olanzapine that produced a half-maximal increase in ACh release (EC50), and the amount of variance in ACh release that was accounted for by the concentration of olanzapine (r2). The sigmoidal concentration-response regression equation was Y = Bottom + (Top − Bottom)/(1 + 10(LogEC50-X)). Y was the percent of control ACh release, Bottom was the percent of control ACh release during dialysis with Ringer's solution (control), Top was the maximal increase in ACh release caused by olanzapine, and X was the logarithm of the olanzapine concentration. The effect of olanzapine on EEG power in the delta range (0.5-4 Hz) was evaluated using repeated-measures ANOVA and post hoc tests adjusted for multiple comparisons by the Bonferroni correction. The effects of leptin replacement on ACh release were analyzed by fitting an ANOVA model with unequal variances across groups. A Tukey post hoc multiple comparisons test was performed to compare means of the groups and allowed for unequal variances across groups. Statistical tests were performed in consultation with the University of Michigan Center for Statistical Consultation and Research. All data were tested for normality and were found to meet the assumptions of the general linear model. Statistical packages utilized were developed by Statistical Analysis System v9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Prism v4.0c for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Data are reported as mean ± SEM. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Histological Analyses Confirmed that ACh Was Measured from the Prefrontal Cortex and Olanzapine Was Delivered to the Prefrontal Cortex

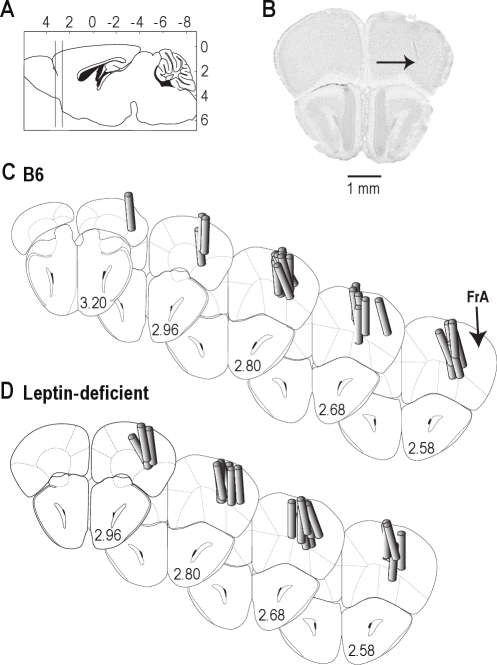

Figure 1 summarizes the results from the histological analysis. Dialysis sites spanned from approximately 2.5 to 3 mm anterior to bregma (Figure 1A). A representative histological section is shown in Figure 1B, with an arrow pointing to the deepest point reached by the microdialysis membrane. Two series of coronal diagrams indicate the location of dialysis sites in B6 (Figure 1C) and leptin-deficient (Figure 1D) mice. Mean ± SEM stereotaxic coordinates31 for the microdialysis sites were 2.7 ± 0.03 mm anterior to bregma, 1.5 ± 0.04 mm lateral to the midline, and 1.9 ± 0.06 mm ventral to the skull surface for B6 mice; and 2.8 ± 0.03 mm anterior to bregma, 1.5 ± 0.05 mm lateral to the midline, and 2.0 ± 0.07 mm ventral to the skull surface for leptin-deficient mice. There was no statistically significant difference between the location of dialysis sites in B6 and leptin-deficient mice.

Figure 1.

Histological analysis confirmed that all microdialysis sites were localized to the prefrontal cortex. (A) Vertical lines on the sagittal diagram of the mouse brain31 delineate the rostral-to-caudal extent of the microdialysis sites in the prefrontal cortex. Numbers at top and right of schematic indicate stereotaxic coordinates in mm, with bregma at 0, 0. (B) A digitized image of a coronal section from the brain of a C57BL/6J (B6) mouse shows a typical microdialysis site (arrow), located approximately 2.7 mm anterior to bregma. (C and D) The coronal diagrams were modified from a mouse brain atlas31 to show the locations of microdialysis sites for 24 B6 (C) and 24 leptin-deficient (D) mice. The prefrontal cortex is labeled as the frontal association area (FrA). Cylinders represent microdialysis membranes and are drawn to scale. Numbers at the lower right of each coronal diagram indicate mm anterior to bregma.

ACh Release in the Prefrontal Cortex Was Stable during Anesthesia and Was Increased by Olanzapine

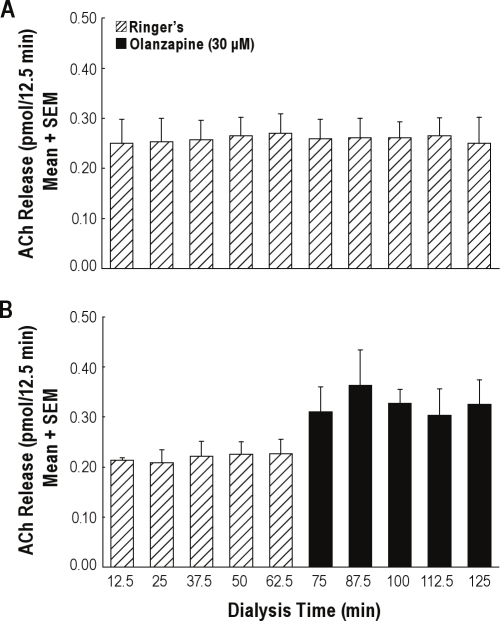

Figure 2A illustrates the time course of ACh release during 125 min of dialysis with Ringer's solution. Data are from three B6 mice and represent average ACh release for 10 sequential dialysis samples per mouse. These control experiments demonstrated that ACh release did not change as a function of the amount of time mice were anesthetized. Similar experiments were performed using leptin-deficient mice, and ACh release was found to be stable throughout the 125-min sample collection period (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Time course of ACh release in the prefrontal cortex of C57BL/6J mouse shows stability and the olanzapine-induced increase. (A) Sequential measures of ACh release during dialysis with Ringer's solution (control). Each bar shows average ACh release from 3 mice. (B) Sequential measures of ACh release during dialysis with Ringer's solution (control) followed by dialysis with olanzapine. Each bar shows data from 3 mice, averaged for each time point.

Figure 2B shows that microdialysis delivery of olanzapine to the prefrontal cortex increased ACh release in the prefrontal cortex. ACh release was measured during dialysis with Ringer's solution (min 12.5-62.5) followed by dialysis with olanzapine (min 75-125). Using this within-subjects design, each mouse served as its own control.

Olanzapine Caused a Concentration-Dependent Increase in ACh Release and Disrupted the Coupling between ACh Release, Recovery Time from General Anesthesia, and Activation of the Cortical EEG

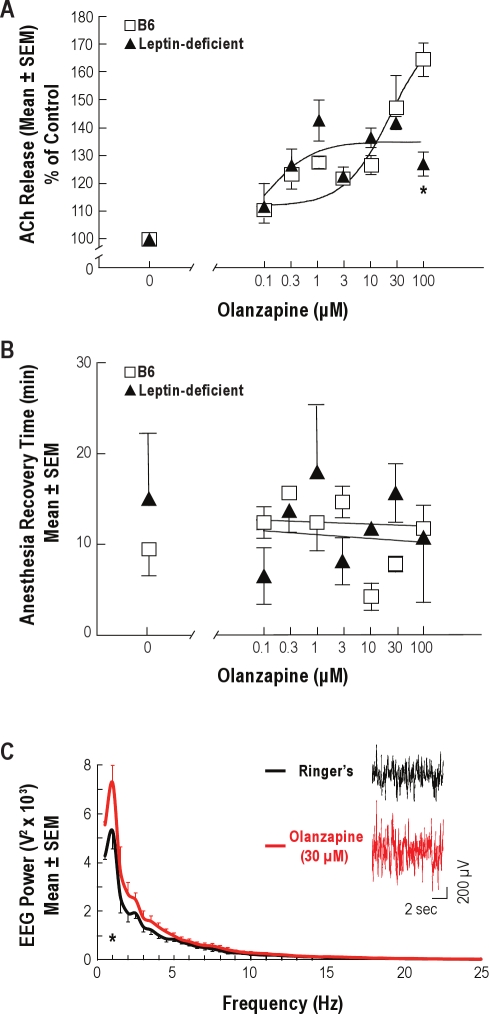

Figure 3A plots the average increase in ACh release caused by microdialysis delivery of olanzapine to the prefrontal cortex of B6 and leptin-deficient mice. Nonlinear regression analysis revealed that the concentration of olanzapine accounted for 74% of the variance in ACh release for B6 mice and 60% of the variance in ACh release for leptin-deficient mice. The EC50 values were 27 μM for B6 mice and 0.117 μM for leptin-deficient mice, indicating that olanzapine was approximately 230-fold more potent for increasing ACh release in leptin-deficient mice than in B6 mice. Two-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant main-effect of olanzapine concentration (F = 19.7; df = 7,32; P < 0.0001), no effect due to mouse line, and a significant mouse line by concentration interaction (F = 4.9; df = 7,32; P < 0.001). Dialysis with 100 μM olanzapine caused a significantly (P < 0.01) greater increase (51%) in ACh release in B6 than in leptin-deficient mice.

Figure 3.

Olanzapine delivered to the prefrontal cortex increased local ACh release and uncoupled the normal correlation of increased ACh release with behavioral and EEG activation. (A) Olanzapine caused a concentration-dependent increase in ACh release in the prefrontal cortex of C57BL/6J (B6) and leptin-deficient mice. Data are from 3 mice per concentration. Olanzapine (100 μM) caused a significantly smaller increase in ACh release in leptin-deficient mice than in B6 mice (*P < 0.01). (B) Olanzapine administered to the prefrontal cortex did not alter recovery time from isoflurane anesthesia. Average anesthesia recovery time for B6 and leptin-deficient mice is plotted as a function of the concentration of olanzapine used for dialysis. Each concentration was tested in 3 mice. (C) Olanzapine increased EEG power in the delta (0.5-4 Hz) range. Average power spectral densities for B6 mice (n = 7) are plotted from data recorded during dialysis with Ringer's solution (control) and with Ringer's solution containing olanzapine (30 μM). Olanzapine significantly (*P < 0.0001) increased EEG power at 1 Hz. Inset shows 10-s recordings of the cortical EEG obtained from the same mouse during dialysis with Ringer's solution and Ringer's solution containing olanzapine.

Previous studies discovered that dialysis delivery of an adenosine A2A receptor agonist to prefrontal cortex of B6 mice significantly increases ACh release in prefrontal cortex and significantly decreases the time required for resumption of wakefulness following isoflurane anesthesia.29 Therefore, the olanzapine-induced increase in ACh release was predicted to cause a shortened recovery time from isoflurane anesthesia. Figure 3B demonstrates, however, that olanzapine did not alter the time required for resumption of righting. Two-way ANOVA showed no significant main effect of mouse line or concentration of olanzapine on recovery time from anesthesia. There was no significant difference in average anesthesia time between B6 (211 ± 2.5 min) and leptin-deficient (206 ± 1.6 min) mice. One-way ANOVA revealed that anesthesia duration did not vary significantly across experiments.

Figure 3C shows EEG power measured from B6 mouse during dialysis of the prefrontal cortex with Ringer's solution and olanzapine (30 μM). Repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of drug treatment on EEG power (F = 13.9; df = 1,6; P < 0.01). Olanzapine caused an increase in EEG slow wave activity.

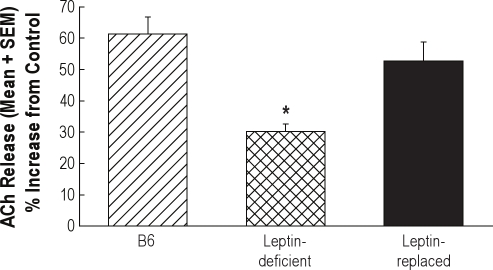

Leptin Replacement in the Leptin-Deficient Mouse Enhanced the Olanzapine-Induced Increase in ACh Release

Figure 4 illustrates the average increase in ACh release within the prefrontal cortex during dialysis delivery of olanzapine to the prefrontal cortex of B6, leptin-deficient, and leptin-replaced mouse. There was a significant treatment main effect on ACh release (F = 11.3; df = 2,12; P < 0.02). In leptin-deficient mice, ACh release was significantly lower than in B6 mice (P < 0.001). Replacement of leptin in the leptin-deficient mice restored ACh release to levels measured in B6 mice. One-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences in the location of microdialysis probes between B6 mice, leptin-deficient mice, and leptin-deficient mice that received leptin replacement. Table 1 shows that treatment with leptin increased plasma levels of leptin in leptin-deficient mice. Leptin-replaced mice lost 21% of their body weight, confirming successful replacement of functional leptin.

Figure 4.

Leptin replacement in leptin-deficient mice enhanced the olanzapine-induced increase in ACh release within the prefrontal cortex. Each bar illustrates the average increase in ACh release from 5 mice during dialysis with olanzapine (100 μM). (Data for 3 of the 5 B6 mice and 3 of the 5 leptin-deficient mice are from Figure 3A.) Leptin-deficient mice showed a significantly (*P < 0.05) smaller olanzapine-induced increase in ACh release compared to B6 mice. The olanzapine-induced increase in ACh release in leptin-replaced mice was not significantly different from the olanzapine-induced increase measured from B6 mice.

Table 1.

Leptin replacement increased circulating leptin levels and decreased body weight in leptin-deficient mice

| Mouse Line | Leptin ± SEM (ng/mL) | % Decrease in Body Weight from Experimental Day 0 ± SEM |

|---|---|---|

| B6 Control | 2.00 ± 0.12 | — |

| Leptin-Deficient Control | 0.02 ± 0.05 | — |

| Leptin-Replaced (Day 7) | 17.89 ± 4.03 | 21.23 ± 1.9 |

Measures of plasma leptin demonstrated that after treatment with leptin for 7 days, leptin-replaced mice showed levels of leptin that were increased compared to leptin-deficient mice. Data are based on 5 mice per group.

DISCUSSION

Microdialysis delivery of olanzapine to the prefrontal cortex of B6 and obese, leptin-deficient mice caused a concentration-dependent increase in ACh release within the prefrontal cortex. In contrast to previous studies showing that pharmacologically increasing ACh release in the prefrontal cortex of B6 mice causes EEG and behavioral arousal,26,27,29 olanzapine dissociated ACh release, behavioral arousal, and EEG activity. Finally, systemic replacement of the satiety hormone leptin in leptin-deficient mice enhanced the olanzapine-induced increase in ACh release. These effects of olanzapine are discussed relative to the modulation of sleep and feeding by the prefrontal cortex, and the mechanisms by which olanzapine caused a dissociation between ACh release, behavioral arousal, and EEG activation.

Prefrontal Cortical Circuits Modulate Food Intake and Sleep

The relevance of obesity for sleep medicine is well documented.39–46 These previous studies have demonstrated an association between sleep, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. The mechanisms underlying this association, however, remain obscure. The most common cause of obesity is a hedonic drive to feed in the absence of caloric deficiency.47 Food consumption in excess of homeostatic need is driven by an anatomically distributed neuronal network. One component of this network is the prefrontal cortex.48 Brain imaging studies indicate that the prefrontal cortex of obese adults49 and obese children50 is activated by feeding to a greater extent than in healthy weight individuals. Interestingly, the prefrontal cortex of humans with insomnia reveals hypermetabolic activity.51 Results consistent with these data from humans have been obtained from B6 mice, in which blockade of adenosine A1 receptors in prefrontal cortex decreases sleep.29 Thus, the prefrontal cortex modulates both hyperphagia and sleep.

The foregoing data provided a strong rationale for testing the hypothesis that olanzapine differentially increases ACh release in prefrontal cortex of normal (B6) and leptin-deficient obese mice. Neuroanatomical and functional data concur that rodent frontal association cortex (Figure 1) is homologous to human prefrontal cortex.32,33,52,53 The results show that olanzapine was more potent (lower EC50) yet less efficacious (smaller maximal response) in leptin-deficient mice than in B6 mice (Figure 3A). These differences between the olanzapine-induced increases in ACh release in B6 and leptin-deficient mice suggest that leptin may play a role in the ACh response to olanzapine. The finding that leptin replacement in leptin-deficient mice enhanced the olanzapine-induced increase in ACh release to levels measured in B6 mice (Figure 4) supports the interpretation that leptin modulates the effects of olanzapine on ACh release in the prefrontal cortex.

Olanzapine Dissociated ACh Release, EEG Activation, and Behavioral Arousal

The present study predicted that olanzapine would increase ACh release in prefrontal cortex of B6 mice based on reports that olanzapine increases ACh release in prefrontal cortex of rat when administered systemically,54 and in hippocampus of rat when administered directly by microdialysis.55 The mechanism by which olanzapine increases ACh release may involve antagonism of muscarinic autoreceptors, which are known to modulate ACh release in the prefrontal cortex of B6 mice.25 Alternatively, the increase in ACh release could be indirect, resulting from olanzapine-induced antagonism of non-cholinergic receptors in the prefrontal cortex. For example, olanzapine also functions as an antagonist at serotonergic, α-adrenergic, and histaminergic receptors.56

Causing an increase in ACh release within the prefrontal cortex has been shown to activate the cortical EEG26,27,29 and increase behavioral arousal, as seen functionally by decreasing recovery time from general anesthesia, increasing time spent awake, and decreasing time spent asleep.29 The present study, however, showed that although olanzapine increased ACh release in the prefrontal cortex, anesthesia recovery time was not changed and olanzapine actually slowed, or deactivated, the cortical EEG (Figure 3). These findings support the interpretation that olanzapine blocked postsynaptic muscarinic receptors in the cortex, thereby preventing behavioral and EEG arousal in response to increased ACh release. This interpretation is consistent with studies showing that olanzapine is highly effective for inhibiting M1 muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in prefrontal cortex of rat.57

Limitations, Potential Clinical Relevance, and Conclusions

Previous data demonstrate that in prefrontal cortex of B6 mouse, muscarinic autoreceptors of the M2 subtype modulate ACh release, EEG slow waves, and EEG spindles.26 The present results do not specify which muscarinic cholinergic receptor subtypes mediate the interaction between ACh release and leptin. Olanzapine antagonizes several different types of neurotransmitter receptors, thus the effects of olanzapine on the dependent measures of ACh release, EEG activity, and anesthesia recovery time are likely to be mediated by diverse neurotransmitter systems in addition to ACh.

Although the present study found that olanzapine delivered directly to the prefrontal cortex causes an increase in slow wave activity in the contralateral cortex (Figure 3C), the effects of olanzapine on sleep were not quantified. In patients with schizophrenia, olanzapine increases sleep efficiency and delta sleep8,58 and causes slowing of the EEG.10,59 In rats, intraperitoneal injection of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist MK-801 has been used to produce some traits of schizophrenia, including sleep disruption.54 In this animal model of schizophrenia, olanzapine reverses the increase in sleep latency and decrease in non-REM (NREM) sleep time caused by MK-801.54 Treatment of normal human volunteers with olanzapine causes an increase in sleep efficiency and time spent in slow wave sleep.60,61 The effects of olanzapine on the sleep of normal mice or rats have not been reported.

The discovery that the bizarre mental activity of dreams occurs during REM sleep62,63 led to the idea that the hallucinations and psychosis of schizophrenia may share common neurobiological mechanisms with dreaming.64,65 EEG recordings revealed that nonmedicated patients with schizophrenia have disturbed sleep characterized by decreases in the amount of stages 3 and 4 sleep and decreased amplitude of delta waves.64 REM sleep abnormalities in nonmedicated patients with schizophrenia were found to include a greater number of REM sleep episodes with shorter mean duration, and a greater number of awakenings during REM sleep or directly after REM sleep.65 These sleep abnormalities are consistent with increased cholinergic tone arising from neurons in the laterodorsal and pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei,66 and fit well with the finding that patients with schizophrenia have an increased number of cholinergic neurons in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus.20,21 No studies have examined the effects of olanzapine on release of ACh from brainstem cholinergic neurons.

The present study did not identify the brain site where leptin acted to increase ACh release in the prefrontal cortex. Leptin may not have had a direct effect on the basal forebrain neurons that provide cholinergic input to the cortex, or on the cholinergic terminals that release ACh within the prefrontal cortex. The leptin that was replaced by continuous systemic infusion is likely to have acted in many brain regions where leptin receptors are expressed, including the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and brainstem.13 In a cell line derived from mouse septal cholinergic neurons, leptin has been shown to increase choline acetyltransferase, the synthetic enzyme for ACh.67 Whether leptin increases ACh synthesis in vivo is not known.

Human obesity due to deficiency of either leptin68 or leptin receptors69 is rare. The present study used leptin-deficient mice not as a model of human obesity, but because these mice provide a unique tool for gaining insight into the modulation of cholinergic neurotransmission by leptin.18,19 The mechanism by which olanzapine and other atypical antipsychotics cause excessive weight gain involves stimulation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus, which in turn causes an increase in food intake.70 Feeding is regulated by a multitude of peptides that also modulate sleep, including leptin,16 hypocretin,71 cholecystokinin,72 ghrelin,73–75 and obestatin.76 Control mechanisms for sleep, energy homeostasis, and feeding interact and overlap.76,77

In conclusion, the data demonstrate that olanzapine delivered to the prefrontal cortex causes a greater increase in ACh release in the prefrontal cortex of B6 mice than in leptin-deficient mice. This study also showed that replacing leptin systemically restores the ACh response to olanzapine in the prefrontal cortex. These findings are relevant to evidence that the prefrontal cortex is dysfunctional in patients with schizophrenia78–80 and to the fact that deactivation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is a defining characteristic of sleep.81

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants MH45361, HL40881, HL65272, and by the Department of Anesthesiology. Dr. A.B. Wathen was supported by T-32 RR007008-30. The authors thank Dr. A.F. Parlow of the National Hormone and Peptide Program at NIDDK for providing the mouse leptin. For expert assistance the authors thank E.A. Gerow, S. Jiang and M.A. Norat from the Department of Anesthesiology, and K. Welch from the University of Michigan Center for Statistical Consultation and Research.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACh

acetylcholine

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- B6

C57BL/6J mouse strain; commonly used for studies of sleep and breathing

- B6.V-Lepob

leptin-deficient, obese mouse; spontaneous point mutation of B6 mouse strain

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- EMG

electromyogram

- FrA

frontal association area

- NREM

non-rapid eye movement

- REM

rapid eye movement

- SEM

standard error of the mean

NOTES ADDED IN PROOF

Recent preclinical data indicate that low dose olanzapine can decrease emesis induced by morphine and diminish sleep disruption caused by ligation of the sciatic nerve.82

Association studies suggest the possibility that a polymorphism of the gene coding for leptin may contribute to olanzapine-induced weight gain in humans.83

REFERENCES

- 1.Miyamoto S, Duncan GE, Marx CE, Lieberman JA. Treatments for schizophrenia: a critical review of pharmacology and mechanisms of action of antipsychotic drugs. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:79–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cipriani A, Rendell J, Geddes JR. Olanzapine in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1729–38. doi: 10.1177/0269881109106900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keck PE., Jr Bipolar depression: a new role for atypical antipsychotics? Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(Suppl 4):34–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth BL, Sheffler D, Potkin SG. Atypical antipsychotic drug actions: unitary or multiple mechanisms for ‘atypicality’? Clin Neurosci Res. 2003;3:108–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner DM, Baldessarini RJ, Waraich P. Modern antipsychotic drugs: a critical overview. CMAJ. 2005;172:1703–11. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grootens KP, Van Veelen NMJ, Peuskens J, et al. Ziprasidone vs olanzapine in recent-onset schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: results of an 8-week double-blind randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:352–61. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pramyothin P, Khaodhiar L. Metabolic syndrome with the atypical antipsychotics. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17:460–6. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32833de61c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salin-Pascual RJ, Herrera-Estrella M, Galicia-Polo L, Laurrabaquio MR. Olanzapine acute administration in schizophrenic patients increases delta sleep and sleep efficiency. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:141–3. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharpley AL, Attenburrow MEJ, Hafizi S, Cowen PJ. Olanzapine increases slow wave sleep and sleep continuity in SSRI-resistant depressed patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:450–4. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wichniak A, Szafranski T, Wierzbicka A, Waliniowska E, Jernajczyk W. Electroencephalogram slowing, sleepiness and treatment response in patients with schizophrenia during olanzapine treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:80–5. doi: 10.1177/0269881105056657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beasley CM, Tollefson GD, Tran PV. Safety of olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(suppl 10):13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sentissi O, Epelbaum J, Olie J-P, Poirier M-F. Leptin and ghrelin levels in patients with schizophrenia during different antipsychotics treatment: a review. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:1189–99. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey J. Leptin: a diverse regulator of neuronal function. J Neurochem. 2007;100:307–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingalls AM, Dickie MM, Snell GD. Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse. J Hered. 1950;41:317–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a106073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372:425–32. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laposky AD, Shelton J, Bass J, Dugovic C, Perrino N, Turek FW. Altered sleep regulation in leptin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R894–903. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00304.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Donnell CP, Tankersley CG, Polotsky VP, Schwartz AR, Smith PL. Leptin, obesity, and respiratory function. Respir Physiol. 2000;119:173–80. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douglas CL, Bowman GN, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. C57BL/6J and B6.V-Lepob mice differ in the cholinergic modulation of sleep and breathing. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:918–29. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00900.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang W, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Leptin replacement restores supraspinal cholinergic antinociception in leptin-deficient obese mice. J Pain. 2009;10:836–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Rill E, Biedermann JA, Chambers T, et al. Mesopontine neurons in schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 1995;66:321–35. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00564-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karson CN, Garcia-Rill E, Biedermann J, Mrak RE, Husain MM, Skinner RD. The brain stem reticular formation in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1991;40:31–48. doi: 10.1016/0925-4927(91)90027-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Rill E. Disorders of the reticular activating system. Med Hypotheses. 1997;49:379–87. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(97)90083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou F-M, Liang Y, Dani JA. Endogenous nicotinic cholinergic activity regulates dopamine release in the striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1224–9. doi: 10.1038/nn769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarter M, Bruno JP. Abnormal regulation of corticopetal cholinergic neurons and impaired information processing in neuropsychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Douglas CL, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. M2 muscarinic autoreceptors modulate acetylcholine release in prefrontal cortex of C57BL/6J mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:960–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douglas CL, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Prefrontal cortex acetylcholine release, EEG slow waves, and spindles are modulated by M2 autoreceptors in C57BL/6J mouse. J Neurophysiol. 2002a;87:2817–22. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Douglas CL, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Postsynaptic muscarinic M1 receptors activate prefrontal cortical EEG of C57BL/6J mouse. J Neurophysiol. 2002b;88:3003–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.00318.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muzur A, Pace-Schott EF, Hobson JA. The prefrontal cortex in sleep. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6:475–81. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01992-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Dort CJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Adenosine A1 and A2A receptors in mouse prefrontal cortex modulate acetylcholine release and behavioral arousal. J Neurosci. 2009;29:871–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4111-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Academies Press. 8th ed. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences Press; 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuster JM. The prefrontal cortex--an update: time is of the essence. Neuron. 2001;30:319–33. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groenewegen H, Uylings H. The prefrontal cortex and the integration of sensory, limbic and autonomic information. Prog Brain Res. 2000;126:3–28. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeMarco GJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Carbachol in the pontine reticular formation of C57BL/6J mouse decreases acetylcholine release in prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2004;123:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flint RR, Chang T, Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. GABAA receptors in the pontine reticular formation of C57BL/6J mouse modulate neurochemical, electrographic, and behavioral phenotypes of wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12301–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1119-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bignall KE. Ontogeny of levels of neural organization: the righting reflex as a model. Exp Neurol. 1974;42:566–73. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(74)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelz MB, Sun Y, Chen J, et al. An essential role for orexins in emergence from general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1309–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707146105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tung A, Szafran MJ, Bluhm B, Mendelson WB. Sleep deprivation potentiates the onset and duration of loss of righting reflex induced by propofol and isoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:906–11. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200210000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan Z, Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Fang J. Sleep is increased by weight gain and decreased by weight loss in mice. Sleep. 2008;31:627–33. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Basta M. Obesity and sleep: A bidirectional association? Sleep. 2010;33:573–4. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Theorell-Haglow J, Bern C, Janson C, Sahlin C, Lindberg E. Association between short sleep duration and central obesity in women. Sleep. 2010;33:583–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004;1:e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Cauter E, Spiegel K, Tasali E, Leproult R. Metabolic consequences of sleep and sleep loss. Sleep Med. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S23–8. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70013-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Pejovic S, Calhoun S, Karataraki M, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with type 2 diabetes: A population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1980–5. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muncey AR, Saulles AR, Koch LG, Britton SL, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Disrupted sleep and delayed recovery from chronic peripheral neuropathy are distinct phenotypes in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1176–85. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f56248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taheri S, Mignot E. Sleep well and stay slim: Dream or reality? Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:475–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-7-201010050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lutter M, Nestler EJ. Homeostatic and hedonic signals interact in the regulation of food intake. J Nutr. 2009;139:629–32. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.097618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perello M, Chuang J-C, Scott MM, Lutter M. Translational neuroscience approaches to hyperphagia. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11549–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2578-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin LE, Holsen LM, Chambers RJ, et al. Neural mechanisms associated with food motivation in obese and healthy weight adults. Obesity. 2010;18:254–60. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davids S, Lauffer H, Thoms K, et al. Increased dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation in obese children during observation of food stimuli. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:94–104. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nofzinger EA, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Price JC, Miewald JM, Kupfer DJ. Functional neuroimaging evidence for hyperarousal in insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2126–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uylings H, Van Eden C, De Bruin M, Feenstra M, Pennartz C, editors. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. Cognition, emotion and autonomic responses: the integrative role of the prefrontal cortex and limbic structures. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Otani S, editor. Boston: Kluwer Academic; 2004. Prefrontal cortex: from synaptic plasticity to cognition. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ichikawa J, Dai J, O'Laughlin IA, Fowler WL, Meltzer HY. Atypical, but not typical, antipsychotic drugs increase cortical acetylcholine release without an effect in the nucleus accumbens or striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:325–39. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson DE, Nedza FM, Spracklin DK, et al. The role of muscarinic receptor antagonism in antipsychotic-induced hippocampal acetylcholine release. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;506:209–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bymaster FP, Nelson DL, DeLapp NW, et al. Antagonism by olanzapine of dopamine D1, serotonin2, muscarinic, histamine H1 and alpha 1-adrenergic receptors in vitro. Schizophr Res. 1999;37:107–22. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyen Q-T, Schroeder LF, Mank M, et al. An in vivo biosensor for neurotransmitter release and in situ receptor activity. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:127–34. doi: 10.1038/nn.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Müller MJ, Rossback W, Mann K, et al. Subchronic effects of olanzapine on sleep EEG in schizophrenic patients with predominantly negative symptoms. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37:157–62. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-827170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schuld A, Kühn M, Haak M, et al. A comparison of the effects of clozapine and olanzapine on the EEG in patients with schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2000;33:109–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giménez S, Clos S, Romero S, Grasa E, Morte A, Barbanoj MJ. Effects of olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol on sleep after a single oral morning dose in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:507–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0633-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharpley AL, Vassallo CM, Cowen PJ. Olanzapine increases slow-wave sleep: evidence for blockade of central 5-HT(2C) receptors in vivo. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:468–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Azerinzky E, Kleitman N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep. Science. 1953;118:273–4. doi: 10.1126/science.118.3062.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dement WC, Kleitman N. Cyclic variations in EEG during sleep and their relation to eye movements, body motility and dreaming. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol. 1957;9:673–90. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(57)90088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caldwell DF, Domino EF. Electroencephalographic and eye movement patterns during sleep in chronic schizophrenic patients. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol. 1967;22:414–20. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(67)90168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jus K, Bouchard M, Jus AK, Villeneuve A, Lachance MA. Sleep EEG studies in untreated, long-term schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;29:386–90. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.04200030074011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watson CJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Neuropharmacology of sleep and wakefulness. Sleep Med Clin. 2010;5:513–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Di Marco A, Demartis A, Gloaguen I, et al. Leptin receptor-mediated regulation of cholinergic neurotransmitter phenotype in cells of central nervous system origin. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:2939–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2000.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, et al. Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature. 1997;387:903–8. doi: 10.1038/43185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Farooqi IS, Wangensteen T, Collins S, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic spectrum of congenital deficiency of the leptin receptor. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:237–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim SF, Huang AS, Snowman AM, Teuscher C, Snyder SH. Antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain mediated by histamine H1 receptor-linked activation of hypothalamic AMP-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3456–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611417104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rodgers RJ, Ishii Y, Halford JCG, Blundell JE. Orexins and appetite regulation. Neuropeptides. 2002;36:303–25. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(02)00085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shemyakin A, Kapás L. L-364,718, a cholecystokinin-A receptor antagonist, suppresses feeding-induced sleep in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R1420–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.5.R1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Szentirmai E, Kapás L, Krueger JM. Ghrelin microinjection into forebrain sites induces wakefulness and feeding in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R575–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00448.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Szentirmai E, Kapás L, Sun Y, Smith RG, Krueger JM. Spontaneous sleep and homeostatic sleep regulation in ghrelin knockout mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R510–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00155.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Szentirmai E, Kapás L, Sun Y, Smith RG, Krueger JM. Restricted feeding-induced sleep, activity, and body temperature changes in normal and preproghrelin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R467–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00557.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Szentirmai E, Kapás L, Sun Y, Smith RG, Krueger JM. The preproghrelin gene is required for the normal integration of thermoregulation and sleep in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14069–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903090106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rolls A, Schaich Borg J, de Lecea L. Sleep and metabolism: role of hypothalamic neuronal circuitry. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:817–28. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gur RE. Closing in on schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1783–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ragland JD, Gur RC, Valdez JN, et al. Levels-of-processing effect on frontotemporal function in schizophrenia during word encoding and recognition. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1840–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tan H-Y, Choo W-C, Fones CSL, Chee MWL. fMRI study of maintenance and manipulation processes within working memory in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1849–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Braun AR, Balkin TJ, Wesenten NJ, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow throughout the sleep-wake cycle. An H215O PET study. Brain. 1997;120:1173–97. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.7.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Torigoe K, Nakahara K, Rahmadi M, et al. Usefulness of olanzapine as an adjunct to opioid treatment and for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:159–69. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c7e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lett TAP, Wallace TJM, Chowdhury NI, Tiwari AK, Kennedy JL, Müller DJ. Pharmacogenetics of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: review and clinical implications. Mol Psychiatry advance. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.109. online publication, 6 September 2011; doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]