Abstract

Objective

To review a quality control and quality assurance (QC/QA) model established to ensure the validity and reliability of collection, storage, and analysis of biological outcome data, and to promote good laboratory practices and sustained operational improvements in international clinical laboratories.

Methods

A two-arm randomized community-level HIV behavioral intervention trial was conducted in five countries: China, India, Peru, Russia, and Zimbabwe. The trial was based on diffusion theory utilizing a Community Popular Opinion Leaders (C-POL) intervention model with behavioral and biological outcomes. The model was established by the Biological Outcome Workgroup (BOWG), which collaborated with the Data Coordinating Center (DCC) and John Hopkins University Reference Laboratory. Five international laboratories conducted Chlamydia/gonorrhea PCR, HSV2 EIA, Syphilis RPR/TPPA, HIV EIA/Western Blot, and trichomonas culture. Data were collected at baseline, 12, and 24 months.

Results

Laboratory performance and infrastructure improved throughout the trial. Recommendations for improvement were consistently followed.

Conclusions

Quality laboratories in resource-poor settings can be established, operating standards can be improved, and certification can be obtained with consistent training, monitoring, and technical support. Building collaborative partnership relations can establish a sustainable network for clinical trials, and can lead to accreditation and international laboratory development.

Keywords: Laboratory Training Partnerships, Resource-poor countries, Capacity building, STDs/HIV, Biological markers of sexual behavior

Introduction

Quality laboratory testing is essential for clinical diagnosis, infectious disease surveillance, and the development of public health policy. Good laboratory practices can be cost-effective, foster good patient care, and ensure the allocation of scarce public health funds based on reliable surveillance.

Excellent laboratories are essential in improving public health in resource constrained countries.1,2 Accurate diagnostic testing is often cost effective because limited therapy can be apportioned correctly. In Tanzania, malaria is frequently over-diagnosed in patients with severe febrile illness, notably in adults and people living in areas with low to moderate transmission.3 This may be associated with a failure to treat alternative causes of severe infection, making the case that diagnosis must be improved. In these situations where diagnosis is inflated, then routine hospital data may overestimate the mortality from malaria, by more than 50 percent. This results in the Ministry of Health providing more resources for malaria and ignoring other diseases that may be just as pernicious.4

As the burden of infectious diseases continues to devastate resource poor countries, the lack of accurate diagnostic tests represents an impediment to good patient care.5 Laboratories also play fundamental roles in the detection of new infectious diseases, antibiotic resistance, food borne infection outbreaks, and agents of bioterrorism.6–9

The provision of quality laboratory services and the conduct of reliable diagnostic testing are challenging in many international settings where resources are limited.1 An initial challenge is the shortage of trained laboratory managers and technicians in resource constrained countries. Additionally, there may be few laboratories that are available to conduct research, because they are primarily dedicated to clinical work, and there may not be a laboratory within easy commuting distance of the rural research site, which requires arrangements for storage and transport of specimens. There may be inadequate laboratory equipment, especially subzero freezers, available for long-term storage of specimens to address quality assurance. If there are freezers and equipment, there may not be a reliable power supply and as a result, heavy duty generators are needed to ensure the integrity of specimens. The final challenge of shipping specimens by air to a reference laboratory for confirmatory testing is becoming increasingly difficult because air carriers are reluctant to carry biohazard packages with passengers.

When developing international laboratories for collaborative research, partnerships where there is regular and on-going two-way communication and technical assistance are essential. Partnership with personnel in international laboratories is also necessary to sustain operational improvements and to achieve accreditation of these laboratories to support clinical trials.

Our objectives were to review a quality control and quality assurance (QC/QA) model established to ensure the validity and reliability of collection, storage and analysis of biological outcome data, and to promote good laboratory practices and sustained operational improvements in international clinical laboratories. We aimed to assess the impact of International laboratory partnerships on the performance of HIV/STD Testing in five resource constrained countries. We discuss the process of improving the training of staff and infrastructure of international laboratories. The QC/QA program team consisted of the National Institute of Mental Health (NMH) trial staff, The Research Triangle Institute (RTI) trial staff, and the staff of the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) International Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Reference Laboratory.

Methods

Trial Methodological Overview

A two-arm randomized community-level HIV behavioral intervention trial (Trial) was conducted in five countries: China, India, Peru, Russia, and Zimbabwe.10,11

The Trial was based on diffusion theory utilizing a Community Popular Opinion Leader (C-POL) intervention model with both a behavioral and biological outcome.12 In each country, an ethnographic study was conducted to identify high risk populations with high prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and HIV-related risk behaviors.13 This study also ascertained the venues where these high risk populations socialized and identified popular opinion leaders whose advice was respected in each group. The pilot study was an opportunity to collect data on HIV/STD risk behaviors and document the prevalence of HIV and STDs to ensure that the populations and venues had sufficient risk to detect a difference between the treatment and comparison condition.14

After this pilot study, the Trial was implemented using a common intervention trial protocol. Each site conducted in-depth risk behavioral assessment interviews at baseline, 12 month, and 24 month assessments with 40 to 188 participants recruited in each of the 20 to 40 community venues per country, HIV/STD testing and counseling, and treatment of incident cases. 18,147 research participants from 138 venues were enrolled in the trial and approximately 54,438 specimens were collected over the three time points. Following baseline data collection, venues in each country were matched and randomized to either receive an AIDS education activities comparison condition or an experimental intervention consisting of the AIDS education activities and the C-POL HIV/STD prevention program. Although the trial’s design and methods are briefly described here, a more thorough description was published in AIDS.10

Venues and Populations

The Trial was conducted in community venues that were social congregating points for the high-risk population in each country because the intervention requires informal opportunities for conversations during which the trained C-POLs can deliver messages endorsing HIV/STD prevention. While the research staff in each country trained the C-POLs, the C-POLs actually delivered the intervention by providing prevention messages to their friends and neighbors.

In three countries, a venue consisted of a physical structure in which population members lived (trade school dormitories in St. Petersburg, Russia), drank alcohol and socialized (wine shops in Chennai, India), or worked (vendor markets in Fuzhou, China). In the other two countries, a venue was defined as a neighborhood setting, such as barrios in Peru and growth point neighborhoods in rural Zimbabwe. Study venues and populations have been described.15 There was a core age range from 18 to 49 years. However, because the inclusion of study populations was based on HIV-related high risk behaviors and STD prevalence, there were differences in ages: China (18–46 years), India (18–40 years), Peru (19–30 years), Russia (18–30 years), and Zimbabwe (18–30 years).

Study Management and Design

The Trial was approved by the Investigational Review Boards (IRB) of each of the Individual U.S. and International Study Sites. Consent was obtained from study participants for the collection of behavioral data and biological samples for testing. Serum samples and either urine samples (males) or self-administered vaginal swabs (females) were obtained from each participant at three times points. Samples were analyzed for HIV, Herpes simplex virus-2, syphilis, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis.

The trial was funded through the cooperative agreement mechanism that is used by NIH, when the supporting institute intends to be involved in both the conduct and monitoring of the trial. The NIMH staff collaborator served as a member of the Scientific Steering Committee and the NIMH Project Officer served as the administrative and budget person for the U10 grants. NIMH also appointed a Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) to review the conduct of the trial.

The Steering Committee was composed of a U.S. and in-country principal investigators (PI) from each site, the PI of the Data Coordinating Center (DCC), and the Staff Collaborator from NIMH. This Committee coordinated the development of the study protocol and established a Biological Outcome Workgroup (BOWG), which developed the procedures for ensuring a valid biological outcome. Members of the BOWG worked closely with the staff of the JHU International Reference Laboratory to recommend commercial test kit selection and laboratory equipment, establish cut points for determining a positive STD, to establish the rules for determining incident STDs, and to develop and review all training materials.

QC/QA Model

Quality control procedures are the methods used to ensure that data are collected in a standardized way and that the intervention was implemented in a similar fashion across sites with fidelity to the intervention manual. Quality assurance procedures documented adherence to the protocol and study procedures, assessment, and intervention. This trial adopted the QC/QA model used in several other randomized clinical trials (RCTs) supported by NIMH. This model was discussed more extensively in other publications.16,17

Model for Quality Assessment/Quality Control

The model contained three major components for QC/QA: quality: (1) personnel and training, (2) manuals for the multi-country study; and (3) ongoing QA monitoring of study procedures. The QC/QA model covered assessment, intervention, and data management, but this discussion is limited to the biological sample collection, storage, and analysis.

Personnel and Training

Performance criteria were established for laboratory technicians. There was extensive didactic and hands on training prior to and during the conduct of the trial by the JHU Reference Laboratory. Laboratory personnel at each international site were trained to use standardized protocols for performing assays and analyzing results for the six STDs measured in the trial. At the end of training and during QA site visits, the performance of laboratory technicians was assessed using specific criteria and if they achieved criterion, they were certified.

Manuals

Several manuals were developed for the biological collection, storage, and analysis. One was a training manual that was used for the initial training sessions and for reference and training new personnel. The other was a Laboratory Procedures Manual which included specific procedures established by the BOWG and the JHU Reference Laboratory, which was comprehensive and specified the qualifications, training, and documentation for laboratory staff for the testing protocols for each STD.

Quality Assurance Procedures

For quality assurance (QA) purposes, RTI, and the JHU reference laboratory provided on-going support for consultation, training, and quality assurance site visits.

Training and Certification

The JHU Reference Laboratory facilitated the conduct of good laboratory practices (GLP) through ongoing training of site laboratory mangers and technicians. Initial training of laboratory managers and technicians was conducted early in 2001, using a train-the-trainers model prior to pre-baseline activities by NIMH, RTI, and the JHU Reference Laboratory in Baltimore, Maryland. Comprehensive training included: ethics, overview of study activities, sample handling and storage, hands-on-testing of samples using all diagnostic tests, and preparation of specimens for international and domestic shipment with International Air Transportation Association (IATA) standards.

In the following year, laboratory managers and technicians were invited to attend a second week-long training session, conducted at the JHU Reference Laboratory. As with the initial training participants worked side-by-side with a JHU Reference Laboratory technician to perform the assays. Participants were provided several panels with which they performed HIV-EIA Vironostika® (BioMérieux, Netherlands,) Western Blot (Bio-Rad, USA), ; RPR Macro-Vue™ Card (Becton-Dickenson (BD), USA),) TPPA Serodia® (Fujirebio Inc., Japan)-; HSV-2 EIA HerpeSelect™ (Focus Diagnostics, USA), ); CT/NG Amplicor® PCR for Chlamydia and gonorrhea (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), and Trichomonas InPouch™ culture test (BioMed Diagnostics, USA).. Panels contained 42 specimens for CT/Ng, 25 for RPR, HIV and HSV. Each set was comprised of positives and negatives. Performance of the training participants was assessed by observing their testing technique and accuracy of their results with selected panels. Trichomonas panels were not used in challenge, rather a positive and negative sample was provided for viewing microscopically. Follow up training was provided during site visits.

Additional trainings were conducted on site, each year or as needed. On site training focused of areas which required improvement, as stated by the site managers and/or as noted by any performance gaps. During each site visit JHU staff member reviewed testing techniques and testing practices. On-site training included chemical hygiene, electrical safety, fire safety, blood borne pathogens, and biohazard waste and specimen handling.

Laboratories

For this trial two new laboratories were established (in India and Russia) and two laboratories were upgraded (in China and Zimbabwe). The fifth was a U.S. military laboratory in Peru. In India and Russia buildings were not constructed, rather existing generic spaces were renovated to suit the testing scheme, and comply with internationally accepted lab design standards, guidelines, and practices. This included proper lighting, ventilation, temperature and humidity controls, as well as provisions for storage and back up power supply. Upgrades in China and Zimbabwe were relevant to temperature, lighting and ventilation. Each laboratory made adjustments to ensure proper safety practices were followed, and that sample handling and storage practices were optimal. For example; proper windows and doors were installed if need and remained closed to ensure consistent temperature and humidity. Significant adjustments were made in all laboratories except Peru. In Peru, Storage and safety was enhanced consistent with continuous quality improvement initiatives. Adjustments and renovations began in early 2001 and were completed by all labs late in 2002. These laboratories were charged with collecting, storing, and analyzing the biological samples.

Staff at RTI and the JHU Reference Laboratory developed a standard list with which each site ordered laboratory supplies and equipment. Timing was critical because the kits needed to arrive in time to begin the study but not so early that the kits expired before all the IRB clearances were received and the study began.

Quality Assurance Panels

After the initial training (2001), quality assurance panels (N=300) were prepared by the JHU Reference Laboratory, containing multiple known positive and negative test specimens for the various type test protocols. Known positive samples were selected first, while additional negative samples were added to the panel to reach the 300 specimen count. These biological specimens were shipped frozen on dry ice from the JHU Reference Laboratory according to IATA guidelines to each site laboratory for testing. The shipper ensured that the specimens were kept frozen, by refreshing the dry ice as needed. The JHU Reference Lab required a shipping permit issued by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in order to ship biohazardous materials. The permit was renewed annually. Each site was required to begin testing as soon as possible upon receipt. Specimens were kept frozen until testing was conducted. After testing, the country laboratories returned the results to the JHU Reference Laboratory to review for concordance.

To further ensure quality, in 2003 the laboratories from each site enrolled in the College of American Pathology (CAP) proficiency testing (PT) program. If available, the site laboratories were enrolled in local proficiency testing programs as well. All proficiency testing and comparison testing evaluations were reviewed monthly by the site laboratory managers and the personnel at the JHU Reference Laboratory. Laboratory managers were required to submit a monthly report, Quality Assurance Report Form, to RTI and JHU.

Laboratory Management System (LMS)

Another critical component of the QC/QA model was the development of the Laboratory Management System (LMS) in response to a need expressed by the laboratory managers and technicians to track testing activities in the laboratory to ensure accuracy and quality management of the results. It was designed by RTI programmers in collaboration with the JHU Reference Laboratory. The LMS was a Microsoft Access 2000-based application that provided a standardized electronic data management system and functioned as an operations support system for laboratories. LMS users documented receipt of specimens; tests conducted and results, and identified missing data.

The LMS facilitated tailoring to the needs of each site. The LMS permitted designated laboratory staff to program and update the cut off values for assays. Possible ranges for test results were programmed into the system and reduced data entry error, further enhancing data quality and reducing time involved with cleaning data. Additionally, laboratory staff members were able to run management reports, generated by the system, to ensure continuous quality improvement. Workload statistics, generated by LMS, measured the work effort required to conduct tests, aiding administrators in making staffing and workload decisions. This system streamlined workflow in the laboratory and reduced paperwork. Some of the laboratory staff noted their dislike of the LMS data verification features, which they viewed as redundant, yet it was used successfully at each site.

Quality Assurance Site Visits

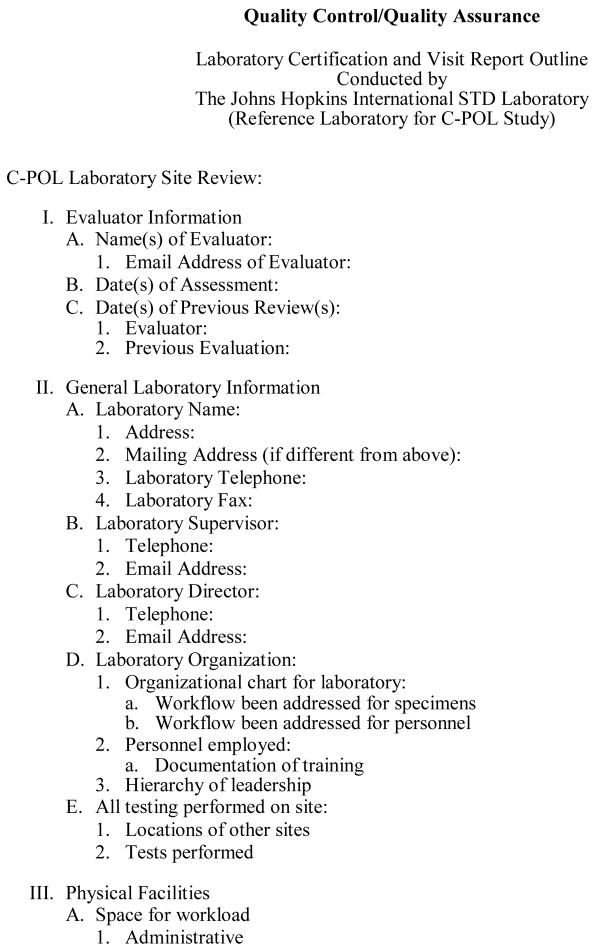

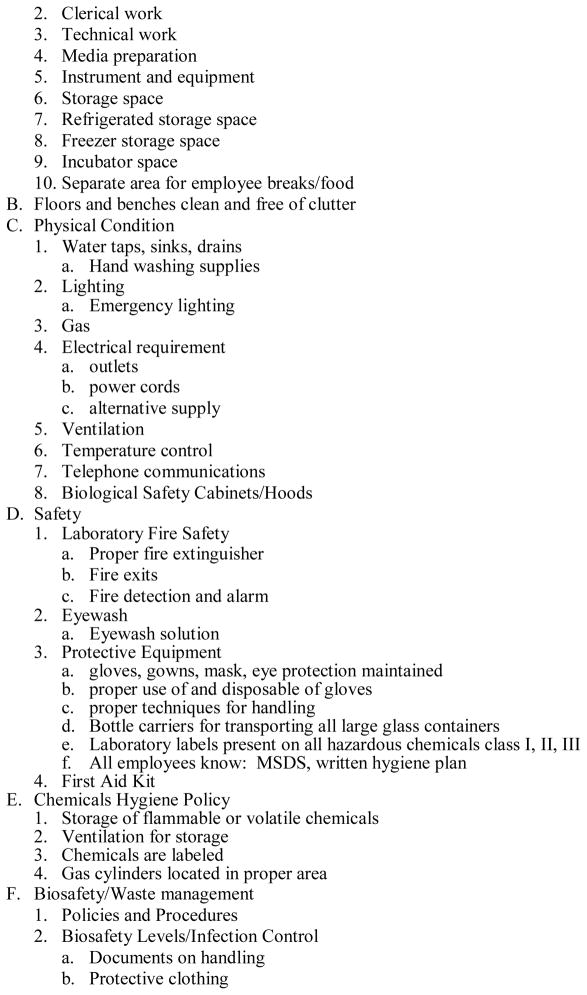

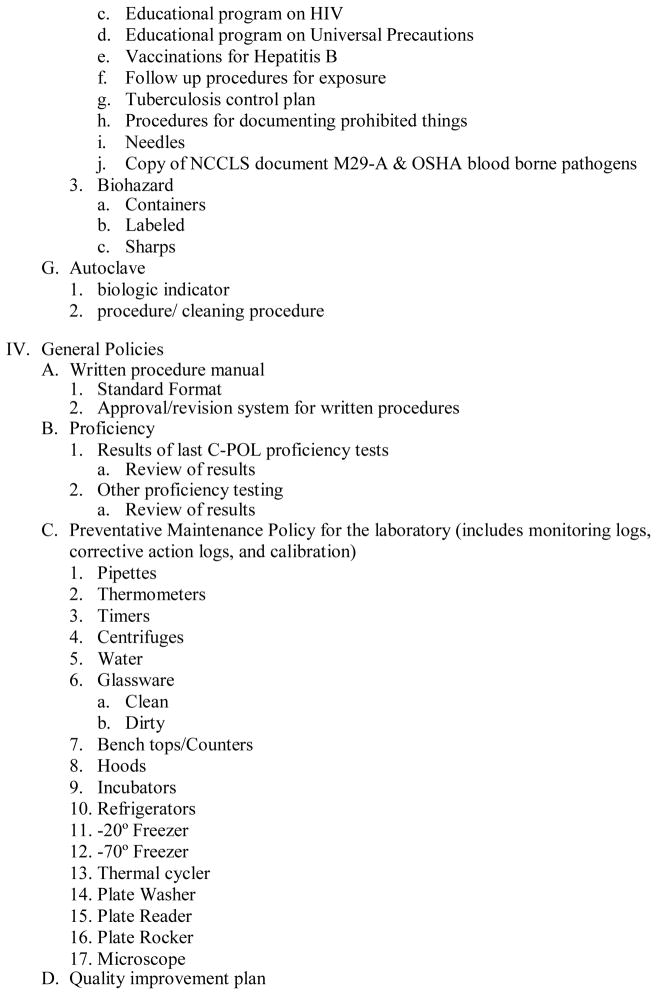

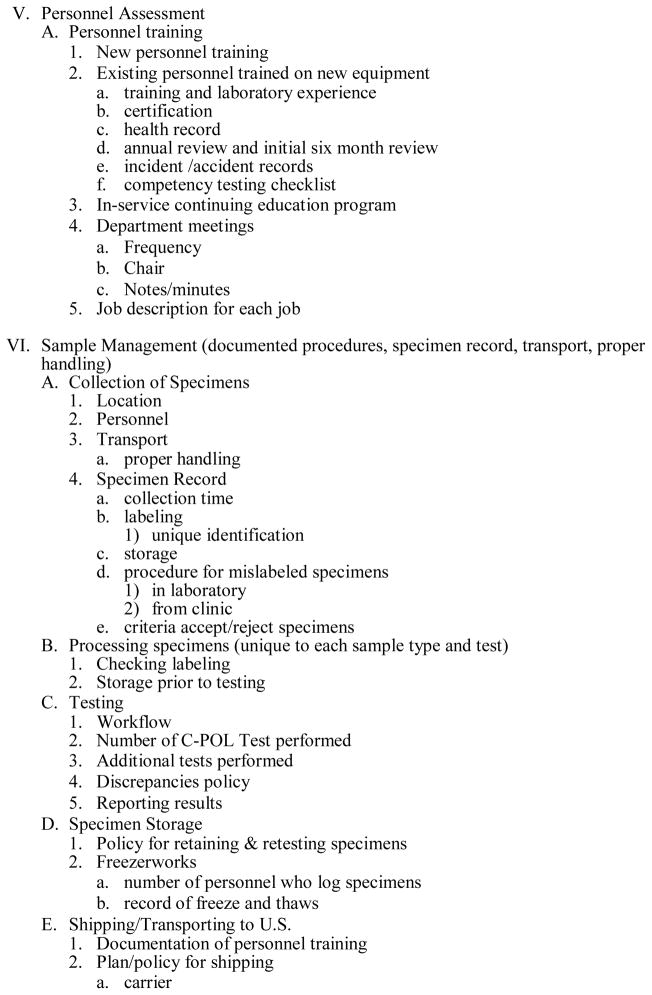

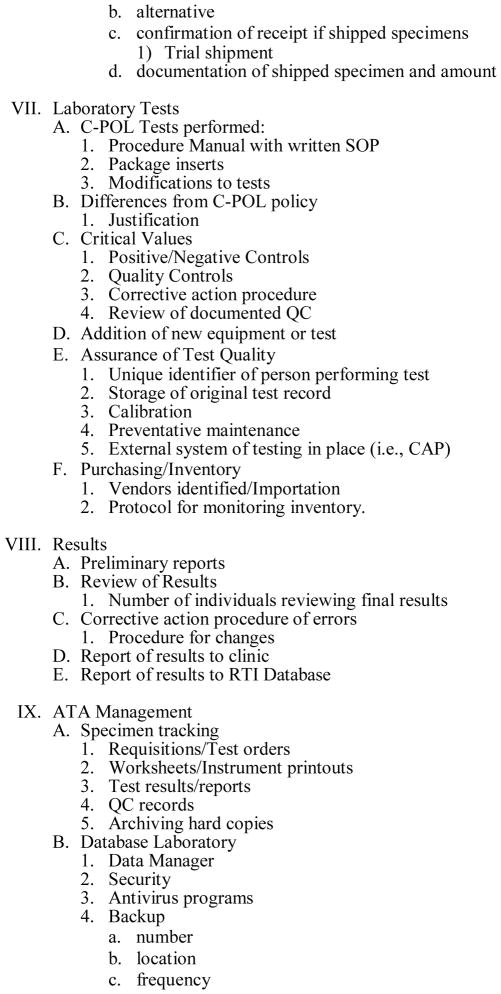

A Laboratory Certification and a Site Visit Report Outline were developed to establish the framework for the site visit (Exhibit A). A comprehensive Site Visit Report was prepared and completed by the QA laboratory monitor at each visit. This Report covered all areas of the laboratory visit outline, and provided recommendation for improvement. These documents ensured that the QA laboratory monitor attended to all the issues and that adequate documentation was made to identify opportunities for improvement as well as ensure that corrective actions were taken by the site laboratory managers. The QA laboratory monitor also recommended a category of performance evaluation of the laboratory based on observation and performance (Table 1).

Exhibit A.

NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial

Table 1.

Categories of Laboratory Evaluation

| Higher Standard Approval | Adheres to and exceeds study protocols, by demonstrating a higher performance standard according to GLP, ISO, CMS/CLIA regulatory requirements, up to and including the “gold standard” of operations according to CAP. |

| Approval | Adheres to study protocols and GLP; no action items which affect test results and/or patient safety; suggestions provided for a higher performance level. |

| Provisional Approval | Adheres to critical requirements of study protocols and GLP; protocol and GLP-related action items identified which do not affect test results; resolution of action items required in writing for achieving or maintaining accreditation. May be resolved during the site visit. |

| Probationer Approval | Does not adhere to critical requirements of study protocol and GLP; GLP and protocol-related action items identified affect test results and/or patient safety. Resolution of action items: each item in writing, written confirmation of corrective action to demonstrate consistent resolution. Resolution will be confirmed during future site visit. Testing may be suspended. |

| Denial or Revocation | Does not adhere to critical requirements of study protocol and GLP; multiple GLP and protocol-related action items identified, including those which affect test results and/or patient safety — testing is suspended; resolve action items in writing with written confirmation of corrective action and consistent improvement, testing may only be resumed after next site visit. |

Confirmatory Testing of Samples

Because two laboratories were established for this study and two others were upgraded and with the trial complexity, the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) was concerned about the validity and reliability of the test results. Each site was required to ship 20% of the samples collected at each site to the JHU reference laboratory for retesting. RTI selected an “enriched” sample, which included all positive samples (where prevalence was <10%) and a random sample of the remaining samples to equal 20% of the total number of samples in the study. Repeated tests included Chlamydia/gonorrhea PCR, HSV2 EIA, Syphilis RPR/TPPA, HIV EIA EIA/Western Blot. Each site sent baseline samples and follow-up sample shipments to the JHU Reference Laboratory for confirmatory testing every six months. After consistent satisfactory performance scores were achieved, sites were allowed to reduce the shipment from 20% to 5% for all retests except CT/NG, which remained at 20% throughout the study.4

Communication with Laboratory Managers

Conference calls with the laboratory managers were held monthly to discuss laboratory operational issues, the performance of proficiency testing, and various other QA and laboratory-related issues. Each laboratory manager submitted the monthly Quality Assurance Report Form to the Reference laboratory and RTI, which detailed the daily laboratory activities.

As part of the QA site visit, the Reference Laboratory monitor conducted assessments and training when laboratory technicians were not achieving criteria. The Reference Laboratory monitor also provided training on specific items per request. Instruction included a review of laboratory techniques, safety guidelines, testing and study protocols, clinical diagnostics, equipment preventive maintenance, and quality assessment practices. The QA laboratory monitor performed an annual laboratory site visit or as needed, if problems were identified.

The QA laboratory monitor reviewed all laboratory operations and discussed any concerns with the laboratory managers. Formal reports and recommendations were prepared and sent to RTI who then shared them with the in-country Principle Investigator, laboratory manager, and NIMH who forwarded them to the DSMB. Reports included findings on adherence to the protocol, GLPs, safety regulations, and recommendations for improvement. The goal of these recommendations was to improve the evaluation level (e.g., from Approval to Higher Standard Approval) of the laboratory by decreasing laboratory errors, improving safety practices, ensuring adherence to C-POL protocol, and training laboratory staff in good laboratory practices, U.S. legislation, and guidelines regarding safety and quality in the laboratory/clinical workplace (Exhibit D). Over time the quality of the laboratories improved and errors were reduced (Figure 3).

Results

The QC/QA model adopted in this study was effective. The detailed training manuals and the Laboratory Procedures Manual used in training sessions ensured that the collection, storage, and analysis of the specimens were valid, reliable and adherent to the study protocol. The ongoing training by RTI and the JHU reference laboratory was effective. Using a train-the-trainers model and forming a partnership with the laboratory managers worked well. This was demonstrated by the good concordance rates between the site laboratories and the JHU Reference Laboratory and the improvement in performance by the country laboratories on the CAP proficiency panels, annually. Sample rejection rates and sample handling, storage, and other sample integrity errors were less than 1%.

The results of the second laboratory managers training on testing, operational issues, and protocol development at the JHU Reference Laboratory were excellent. Participants from all five sites performed trichomonas and syphilis testing and scored 100%. Laboratory technicians from three sites performed HIV EIA and WB, with 100% correct EIAs detecting positives (1 false positive EIA; correct as negative by WB), while 90% reported correct WB results (indeterminate as called positive or positive called indeterminate represented occasional interpretation errors). Participants from two sites performed CT/NG PCR testing; one site had 100% correct results, and one site found one false positive on both tests. In that case, there was an interpretation error, which was corrected after review.

Site laboratory technicians performed well when the panels developed by the JHU Reference Laboratory were shipped to the site laboratories and tested. The panel proficiency testing results demonstrating performance scores from year one in Table 2. (Zimbabwe did not participate in year 1 testing). Table 3 shows concordance of site results of the first 20% retested samples by technicians at the JHU reference laboratory. Discordant results were retested by both the JHU Reference Laboratory and the site laboratory and discordant results were resolved.

Table 2.

Reference Laboratory Quality Control Proficiency Panel Results for In-Country Laboratories for STDs/HIV in Year One

| Quality Control Proficiency Panel Results

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | HIV EIA* (n=92) | HIV WB** (n=10) | HSV2* (n=42) | RPR* (n=25) | TPPA** (n=10) | CT PCR* (n=44) | GC PCR* (n=44) |

| China | 100/66 | 100 | 100/78 | 100/100 | 100 | 100/100 | 100/100 |

| India | 100/100 | 100 | 100/100 | 100/100 | 100 | 100/100 | 100/100 |

| Peru | 100/85 | 100 | 100/100 | 100/100 | 100 | 100/92 | 80/100 |

| Russia | 100/100 | 100 | 100/100 | 100/100 | 100 | 87/100 | 88/100 |

Sensitivity/Specificity (%)

Percent Agreement (%)

Table 3.

Results of Reference Laboratory Quality Assurance Retesting of 20% of Specimens First Tested by 5 In-Country Laboratories for STDs/HIV in Year One

| 20% Sample Retesting Results (n=300/site for each test)

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | HIV EIA* | HIV WB** | HSV2* | RPR* | TPPA** | CT PCR* | GC PCR* |

| China | NA/97 | 100 | 92/92 | 89/97 | 100 | 100/100 | 77/100 |

| India | 69/98 | 92 | 100/100 | 82/100 | 100 | 98/100 | 100/100 |

| Peru | 100/100 | 50 | 96/92 | 88/100 | 100 | 100/95 | 50/100 |

| Russia | 86/86 | 100 | 98/93 | 100/99 | 100 | 100/95 | 100/98 |

| Zimbabwe | 97/90 | 100 | 98/96 | 90/98 | 96 | 100/98 | 100/99 |

% Sensitivity/% Specificity

Percent Agreement (%),

NA-not able to be calculated

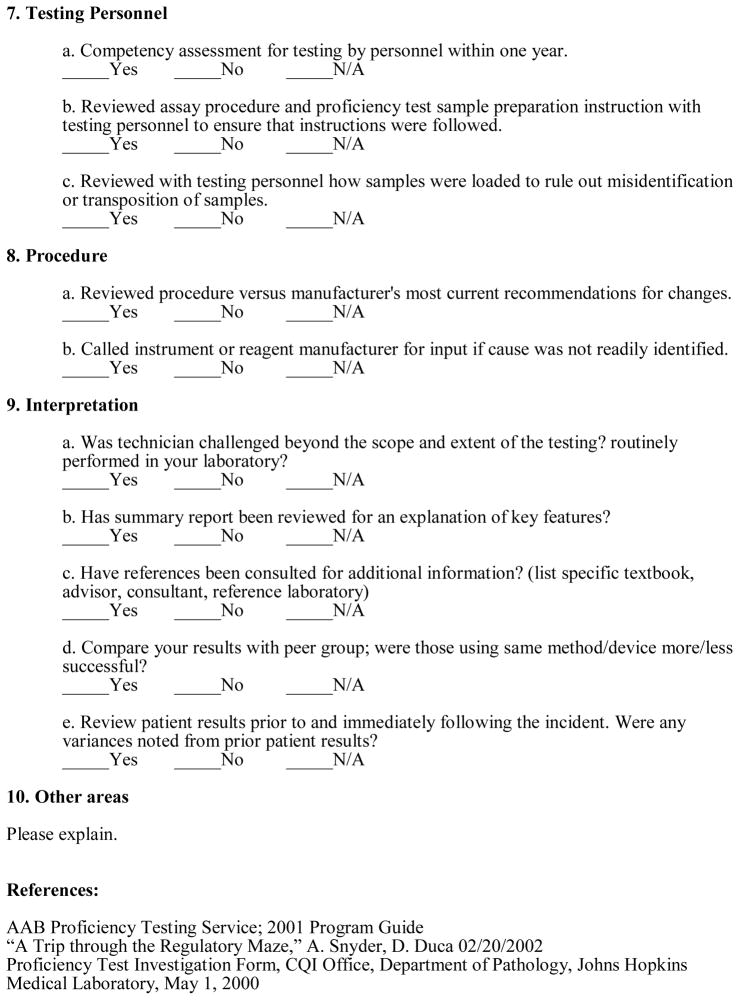

Laboratory operations and facilities in all five countries improved throughout the conduct of the trial. Recommendations for improvement by the JHU Reference Laboratory were consistently implemented by site laboratories (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Error Rates and Non-compliance Rates: Percentage (%) of Laboratories Approved for Testing, and Laboratories (%) Operating at a Higher Level; from Reference Laboratory Site Visit Inspection Results of the 5 C-POL Trial Laboratories Conducted Over Time.

Over time all sites successfully met performance criteria, demonstrated progressive improvement, adhered to study protocols, and were given ratings of either “Approval” to perform laboratory testing or deemed as “Higher Standard Approval.” Corrective actions, as recommended in the Site Visit Reports were followed and maintained in all areas. By the next site visit, four out of five (80%) of all sites had reached the ”Higher Standard Approval” positioning them for a more formal accreditation by a certified accrediting agency, such as CAP (Table 1, Figure 1.) Suggested corrective actions within the Site Visit Report served as a work plan and a tool for the laboratory managers identifying weaknesses. Corrective Actions included activities such as, ensuring that procedure and result review was performed regularly, ensuring that safety equipment was accessible and used, as well as several activities consistent with technical constraints as noted by the lab staff. Some of the technological difficulties encountered by the staff at the various laboratories included; regular performance of controls with each assay; intermittent power supplies; work flow with PCR; issues concerning expiration dates; misinformation about performance of test procedures from local sales representatives and staff from other laboratories; and calibrating equipment. The most difficult assay to institute was the PCR, but training resolved that issue. Ensuring that shipment of lab supplies and testing kits proposed a challenge as at times they could be held in Customs. In hot climates, this especially posed a problem if reagents remained on the airport tarmac until cleared. Proactive communications with shippers resolved these issues.

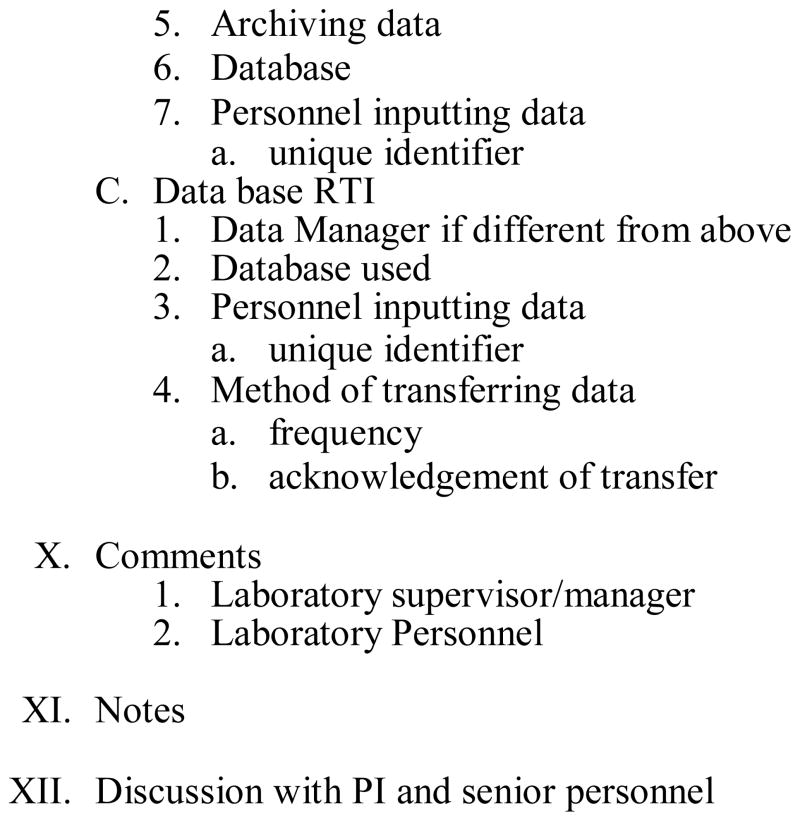

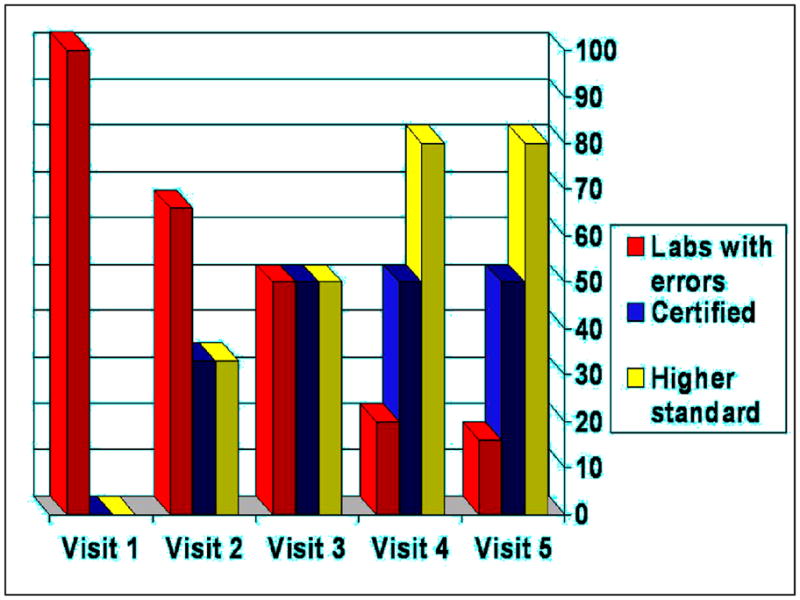

In the first year of enrollment in CAP proficiency testing for CT/GC PCR, which had three surveys with five challenges each, laboratories scores were 80–100% (Figure 2). For the one survey/one challenge HSV-2 EIA test, laboratories scored 100%. For Syphilis RPR/TPPA, with three surveys with five challenges each, laboratories scored between 80–100%. HIV EIA/Western Blot, with three surveys and five challenges each, sites scored between 80–100%. Scores improved after the first proficiency test CAP survey, where two typographical errors were detected but no testing errors occurring. As of 2006, all sites achieved scores of 100% for all proficiency testing panels. For the 2007 surveys, all sites were able to sustain scores of 100%. Laboratories steadily improved over time in proficiency testing for CAP surveys for all test challenges (Figure 2). Over time the quality of the laboratories improved and the errors were reduced (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CAP Proficiency Testing Scores (Number of Errors and Scores [%]) for CPOL Trial Laboratories in Five Countries over Time.

Discussion

Integral to the success of the laboratories, NIMH, RTI, the BOWG, and the JHU Reference Laboratory played key roles in the development of training and performance manuals for all sites; ensured the training and supervision of the collection of biological specimens, and ensured good laboratory practices were adhered to by sites. Participation by staff from the site laboratories, NIMH, RTI, and the JHU Reference Lab in monthly conference calls and periodic meetings, on-going technical support, and working as partners to problem solve, were also key factors in ensuring excellent laboratory performance. Partnership between U.S. laboratories and those in developing countries has proven to be essential in ensuring excellent laboratory performance and building laboratory capacity.

Laboratory testing performance can and should achieve the same level of performance globally to ensure the validity and reliability of results, especially in large multi-country trials. 10,11 Technology transfer, documentation of training and assays performed, site visits, continued quality control testing and ongoing quality assurance programs were integral parts of establishing a network of international laboratories performing STI and HIV diagnostic assays. Cost-effective analysis models in resource-poor settings can add guidance as to the interpretation of investment of resources to improve laboratories in developing countries.18 Public health and policy makers must have accurate diagnoses of diseases, if they are going to effectively allocate resources for public health. Advocacy will be required to raise awareness that it is possible to improve the quality of laboratory diagnostic capability in less-developed countries to ensure their availability. Additionally, good data transfer methodologies and communication are integral components of laboratory quality. Laboratory improvement and quality assessment programs that participate in ongoing training, comparison testing, and formal proficiency testing surveys are essential to quality laboratory testing conducted in international laboratories. For the future, we must not forget the adequate education of medical students in discipline of laboratory medicine in order to maintain proficiency in resource-poor settings.19–20

As more international trials are conducted, well developed laboratories with well trained technicians play an instrumental role in streamlining the assessment of emerging infectious disease events, by correctly utilizing best practices and appropriate laboratory methodologies. Although testing capabilities and technology continue to rapidly expand, detection of many emerging and reemerging pathogens remains difficult for sentinel laboratories because of the cost.21

In conclusion, our experience confirmed that quality international laboratories in resource-poor settings can be established and sustained, operating standards can be improved, and certification can be obtained with consistent facilitation, training, monitoring, partnership, and technical support. Our findings suggest that similar to U.S. practices, quality assessment programs that engage in ongoing training, comparison testing, site visits, and proficiency testing are fundamental to quality diagnostic testing conducted in international laboratories. Building an on-going collaborative relationship also establishes a sustainable network that can provide new options for international laboratories, and lead to a low-cost international training and peer review programs for accreditation and laboratory development.22 Sustainability is always an issue without sustained funding, but once a partnership is formed, a site which has developed laboratory expertise, can continue to participate in proficiency panels and continue to stay in contact with mentors throughout the continued quality improvement process, seeking input where needed. Our findings demonstrated that quality control and quality assurance (QC/QA) model that was established to ensure the validity of the analysis of biological outcome data and to promote good laboratory practices appeared to work well in this study. The impact of the international laboratory partnerships on the performance of HIV/STD testing was encouraging.

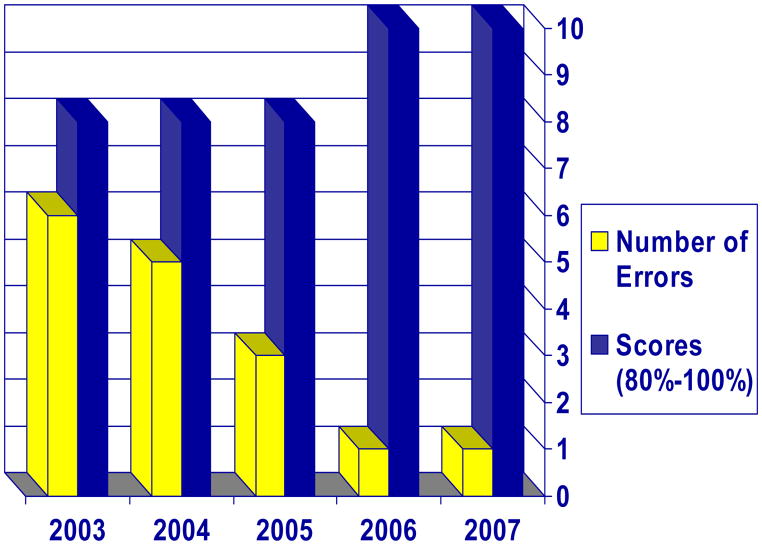

Exhibit B.

NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial

Acknowledgments

Paul Stamper, MT(ASCP), MS, laboratory technicians at each site and the Reference Laboratory technicians.

This study was supported by The National Institute of Mental Health through the Cooperative Agreement mechanism: U10 MH61513, a 5-country Cooperative Agreement conducted in China, India, Peru, Russia, and Zimbabwe, and in part by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH.

Each site selected a different venue and population with which to implement the prevention program entitled “The Community Public Opinion Leader (C-POL) Intervention.”

(U10MH061499, U10MH061513, U10MH061536, U10MH061537, U10MH061543, U10MH061544).

The protocol for collection, storage, and analysis for this Trial was largely developed by the Biological Outcomes Workgroup (BOWG) under the initial leadership of Maria Wawer, Johns Hopkins University.

10. The NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group

MASTHEAD

Research Steering Committee/Site Principal Investigators and NIMH Senior Scientist: Carlos F. Caceres, M.D., Ph.D. (Cayetano Heredia University [UPCH]); David D. Celentano, Sc.D. (Johns Hopkins University); Thomas J. Coates, Ph.D. (David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)); Tyler D. Hartwell, Ph.D. (RTI International1); Danuta Kasprzyk, Ph.D. (Battelle); Jeffrey A. Kelly, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin); Andrei P. Kozlov, Ph.D. (Biomedical Center, St. Petersburg State University); Willo Pequegnat, Ph.D. (National Institute of Mental Health); Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus, Ph.D. [UCLA]); Suniti Solomon, M.D. (YRG Centre for AIDS Research and Education [YRG CARE]); Godfrey Woelk, Ph.D. (University of Zimbabwe Medical School); Zunyou Wu, Ph.D. (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention)

Collaborating Scientists/Co-Investigators: Roman Dyatlov, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center); A.K. Ganesh, A.C.A., B.Com. (YRG CARE); Li Li, Ph.D. (UCLA); Sudha Sivaram, Ph.D., M.P.H. (Johns Hopkins University); Anton M. Somlai, Ed.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin)

Assessment Workgroup: Eric G. Benotsch, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin); Juliana Granskaya, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center); Jihui Guan, M.D. (Fujian Center for Disease Control and Prevention); Martha Lee, Ph.D. (UCLA); Daniel E. Montão, Ph.D. (Battelle)

Biologic Outcomes Workgroup: Nadia Abdala, Ph.D. (Yale University); Roger Detels, M.D., M.S. (UCLA); David Katzenstein, M.D. (Stanford); Jeffrey Klausner, M.D., M.P.H. (San Francisco Department of Public Health, University of California at San Francisco [UCSF]); Kenneth H. Mayer, M.D. (Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI); Michael Merson, M.D. (Yale University)

Ethnography Workgroup: Margaret E. Bentley, Ph.D. (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill); Olga I. Borodkina, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center); Maria Rosa Garate, M.Sc. (UPCH); Vivian F-L. Go, Ph.D. (Johns Hopkins University); Barbara Reed Hartmann, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin); Sethulakshmi Johnson, M.S.W. (YRG CARE); Eli Lieber, Ph.D. (UCLA); Andre Maiorana, M.A., M.P.H. (UCSF); Ximena Salazar, M.Sc. (UPCH); David W. Seal, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin); Nikolai Sokolov, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center); Cynthia Woodsong, Ph.D. (RTI International)

Intervention Workgroup: Walter Chikanya, B.S. (University of Zimbabwe); Nancy H. Corby, Ph.D. (UCLA); Cheryl Gore-Felton, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin); Susan M. Kegeles, Ph.D. (UCSF); Suresh Kumar, M.D. (SAHAI Trust, Chennai, India); Carl Latkin, Ph.D. (Johns Hopkins University); Letitia Reason, Ph.D., M.P.H. (Battelle); Ana Maria Rosasco, B.A. (UPCH); Alla Shaboltas, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center); Janet St. Lawrence, Ph.D. (CDC)

Workgroup on Protecting Human Participants and Ethical Responsibility: Alejandro Llanos-Cuentas, M.D., Ph.D., (UPCH); Stephen F. Morin, Ph.D. (University of California San Francisco)

Laboratory Managers: Pachamuthu Balakrishnan, Ph.D., M.Sc. (YRG CARE); Segundo Leon, M.Sc. (Peru); Patrick Mateta, Spec.Dip.MLSc., M.B.A. (University of Zimbabwe); Stephanie Sun, M.P.H. (UCLA); Sergei Verevochkin, Ph.D. (The Biomedical Center); Youping Yin, Ph.D. (National Center for STD and Leprosy Control, Nanjing, China)

Site Coordinators/Managers: Sherla Greenland, B.S. (University of Zimbabwe); Olga Kozlova, (The Biomedical Center); Reggie Mutsindiri, B.S., R.N. (University of Zimbabwe); Jose Pajuelo, M.D., MPH, (UPCH); Keming Rou (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention); A.K. Srikrishnan, B.A. (YRG CARE); Sheng Wu, M.P.P. (UCLA)

Site Data Managers: S. Anand (YRG CARE); Julio Cuadros Bejar (UPCH); Patricia T. Gundidza, B.S. (University of Zimbabwe); Andrei Kozlov, Jr. (Russia); Wei Luo (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention)

Data Coordinating Center (RTI International): Gordon Cressman, M.S.; Martha DeCain, B.S.; Laxminarayana Ganapathi, Ph.D.; Annette M. Green, M.P.H.; Sylvan B. Green, M.D. (University of Arizona); Nellie I. Hansen, M.P.H.; Sheping Li, Ph.D.; Cindy O. McClintock, B.A.; Deborah W. McFadden, M.B.A.; David L. Myers, Ph.D.; Corette B. Parker, Dr.P.H.; Pauline M. Robinson, M.S.; Donald G. Smith, M.A.; Lisa C. Strader, M.P.H.; Vanessa R. Thorsten, M.P.H.; Pablo Torres, B.S.; Carol L. Woodell, B.S.P.H.

Reference Laboratory: Charlotte A. Gaydos, M.S., M.P.H., MT (ASCP), Dr.P.H.; Tom Quinn, M.D.; Patricia A. Rizzo-Price, M.T., M.S.

Cross-site Quality Control and Quality Assurance: L. Yvonne Stevenson, M.S. (Medical College of Wisconsin)

* All names in alphabetical order

Footnotes

RTI International is a trade name for Research Triangle Institute.

Competing Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Petti CA, Polage CR, Quinn TC, et al. Laboratory medicine in Africa: A barrier to effective health care. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(3):377–82. doi: 10.1086/499363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Building laboratory capacity in support of HIV/AIDS care programs in resource-limited countries: report from a Global AIDS Program meeting; Dec 16–17, 2003; Atlanta, GA: CDC; [Accessed March 1, 2010]. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/dls/ila/cd/who-afro/EmergencyPlanLabCapacityMeetingReportFinal.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reyburn H, Mbatia R, Drakeley C, et al. Over diagnosis of malaria in patients with severe febrile illness in Tanzania: a prospective study. BMJ. 2004;329:1212–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38251.658229.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson ML. Assuring the quality of clinical microbiology test results. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1077–82. doi: 10.1086/592071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urdea M, Penny LA, Olmsted SS, et al. Requirements for high impact diagnostics in the developing world. Nature. 2009;444(Suppl 1):73–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson LR, Hamilton JD, Baron EJ, et al. Role of clinical microbiology laboratories in the management and control of infectious diseases and the delivery of health care. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;32:605–11. doi: 10.1086/318725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pien BC, Saah JR, Miller SE, et al. Use of sentinel laboratories by clinicians to evaluate potential bioterrorism and emerging infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1311–24. doi: 10.1086/503260. Epub 2006 Mar 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cockerill FR, 3rd, Smith TF. Response of the clinical microbiology laboratory to emerging (new) and reemerging infectious diseases. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2359–65. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2359-2365.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snyder JW. Role of the hospital-based microbiology laboratory in preparation for and response to a bioterrorism event. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.1-4.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NIHM Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Methodological overview of a five-country community-level HIV/sexually transmitted disease prevention trial. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl2):S3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266453.18644.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Results of the NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial of a Community Popular Opinion Leader Intervention. JAIDS. 2010;54:204–14. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d61def. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Stevenson LY, et al. Community AIDS/HIV risk reduction: the effects of endorsements by popular people in three cities. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1483–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.11.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial. Design and integration of ethnography within an international behavior change HIV/Sexually transmitted disease prevention trial. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl2):S37–S48. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266456.03397.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NIHM Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevalence and factors in concentrated and generalized HIV epidemic settings. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl2):S81–S90. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266460.56762.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Selection of populations represented in the NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl2):S19–S28. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266454.26268.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NIMH Multisite HIV/STD Prevention Trial. Quality control and quality assurance in HIV Prevention Research: model from a multisite HIV prevention trial. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl2):S49–S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strader LC, Strader LC, Pequegnat W. Developing a quality control/quality assurance program. In: Pequegnat W, Stover E, Boyce CA, editors. How to write a successful research grant application: A guide for social and behavioral scientists. 2. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 309–330. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walensky RP, Ciaranello AL, Park J-E, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Laboratory Monitoring in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of the Current Literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:85–92. doi: 10.1086/653119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith BR, Aguero-Rosenfeld M, Anastasi J, et al. Educating Medical Students in Laboratory Medicine. A Proposed Curriculum. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133:533–542. doi: 10.1309/AJCPQCT94SFERLNI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson ML. Educating Medical Students in Laboratory Medicine (editorial) Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133:525–528. doi: 10.1309/AJCPQIA4FUGMVHT8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baron EJ. Implications for new technology for infectious disease practice. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1318–23. doi: 10.1086/508536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang TA, White NJ, Hien TT, et al. Clinical Research in Resource-Limited Settings: enhancing Research Capacity and Working together to Make Trials Less Complicated. PLoS Neglected Trop Dis. 2010;4:e619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]