Abstract

Background

Influenza pandemic remains a serious threat to human health. Viruses of avian origin, H5N1, H7N7 and H9N2, have repeatedly crossed the species barrier to infect humans. Recently, a novel strain originated from swine has evolved to a pandemic. This study aims at improving our understanding on the pathogenic mechanism of influenza viruses, in particular the role of non-structural (NS1) protein in inducing pro-inflammatory and apoptotic responses.

Methods

Human lung epithelial cells (NCI-H292) was used as an in-vitro model to study cytokine/chemokine production and apoptosis induced by transfection of NS1 mRNA encoded by seven infleunza subtypes (seasonal and pandemic H1, H2, H3, H5, H7, and H9), respectively.

Results

The results showed that CXCL-10/IP10 was most prominently induced (> 1000 folds) and IL-6 was slightly induced (< 10 folds) by all subtypes. A subtype-dependent pattern was observed for CCL-2/MCP-1, CCL3/MIP-1α, CCL-5/RANTES and CXCL-9/MIG; where induction by H5N1 was much higher than all other subtypes examined. All subtypes induced a similar temporal profile of apoptosis following transfection. The level of apoptosis induced by H5N1 was remarkably higher than all others. The cytokine/chemokine and apoptosis inducing ability of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 was similar to previous seasonal strains.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the NS1 protein encoded by H5N1 carries a remarkably different property as compared to other avian and human subtypes, and is one of the keys to its high pathogenicity. NCI-H292 cells system proves to be a good in-vitro model to delineate the property of NS1 proteins.

Keywords: Pandemic influenza, Avian influenza, NS1, Inflammation, Hypercytokinemia, Apoptosis, Pathogenesis

Background

Influenza A viruses are major animal and human pathogens with potential to cause pandemics. Avian subtypes H5N1, H7N7 and H9N2 have repeatedly crossed the species barrier to infect humans [1-8]. Since 2003, there have been repeated outbreaks of H5N1 in poultries and sporadic human infections associated with high mortality [8,9]. The recently emerged swine-origin influenza A virus (2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus - 2009 pdmH1N1) has spread globally within a few months following the initial detection in Mexico and United States in April 2009, resulting in another influenza pandemic as declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on June 11 2009 [10]. Although most of the infections are associated with a mild, self-limiting influenza-like illness; the fact that some severe and even fatal outcomes have been observed in individuals without underlying medical conditions poses concerns regarding the pathogenesis of 2009 pdmH1N1 [11,12].

Previous data on human infection with avian influenza virus indicate that cytokine storm is a key mediator, as well as a predictor, for adverse clinical outcomes; especially the haemophagocytic syndrome commonly seen in severe human influenza A H5N1 infections [4,13-16] The preferential infection of deeper lung cells and the prompt induction of apoptosis may also explain the rapid deterioration in lung function [17]. In short, influenza infection can go through a direct pathogenic pathway by inducing apoptosis, and hence cell death and loss of critical function; and alternatively or most probably at the same time through an indirect pathogenic pathway by inducing excessive cytokine/chemokine production from the infected cells. The state of hypercytokinaemia will then trigger adverse consequences such as haemophagocytic syndrome [18].

The virulence of influenza A virus is a polygenic trait. Multiple molecular interactions are involved in determining the outcome of an influenza infection in certain host species [19-28]. The genome of influenza virus is segmented, consisting of eight single-stranded, negative sense RNA molecules, which encode eleven proteins [29]. These are polymerase basic protein 1 (PB1), PB1-F2 protein, polymerase basic protein 2 (PB2), polymerase acidic protein (PA), hemagglutinin (HA), nucleoprotein (NP), neuraminidase (NA), matrix protein 1 (M1), matrix protein 2 (M2), non-structural protein 1 (NS1) and non-structural protein 2 (NS2) [17]. This study focused on NS1 protein which carries multiple functions including the control of temporal synthesis of viral-specific mRNA and viral genomic RNAs [30,31], and interaction with the cellular protein phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3-kinase) [32-34]; which may cause a delay in virus-induced apoptosis [35]. NS1 protein also has an ability to circumvent the host cell antiviral responses by blocking the activation of RNaseL [36], limiting the induction of interferon (IFN)-β [37-39], interacting with the cellular protein retinoic acid-inducible gene product I (RIG-I) [40-42], blocking host cell mRNA polyadenylation [43,44], blocking the double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR)-mediated inhibition of protein synthesis [31,45], and interacting with cellular PDZ-binding proteins [46]. Furthermore, it has been shown that NS1 protein prevents the maturation of human primary dendritic cells, thereby limiting host T-cell activation [47].

To improve our understanding on the pathogenic mechanism of the newly emerged pandemic strain as well as for influenza viruses in general, we set on this study to examine the property of NS1 proteins encoded by different influenza virus subtypes.

Methods

Virus isolates

This study examined the NS1 proteins encoded by seven strains of influenza A viruses including the newly emerged 2009 pandemic H1N1 (A/Auckland/1/2009) (2009 pdmH1N1), an H2 subtype (A/Asia/57/3) (H2N2), an H5N1 isolated from a fatal case in Thailand (A/Thai/KAN1/2004) (H5N1/2004), an H7N3 isolate (A/Canada/504/2004) (H7N3/2004) which caused conjunctivitis and mild upper respiratory tract infection in humans in Canada, an H9N2 isolate (A/Duck/Hong Kong/Y280/1997) (H9N2/1997) that was closely related to those strains found in human H9N2 infections in Hong Kong, and two previous circulating seasonal influenza strains isolated in 2002 (A/HongKong/CUHK-13003/2002) (H1N1/2002) and 2004 (A/HongKong/CUHK-22910/2004) (H3N2/2004). Stocks of these viruses grown in Mandin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were used.

Cell cultures

The bronchial epithelial cell line, NCI-H292, derived from human lung mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells (ATCC, CRL-1848, Rockville, MD, USA), were grown as monolayers in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (all from Gibco, Life Technology, Rockville, Md., USA) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. NCI-H292 cells were used to study the host cellular response to NS1 proteins.

In-vitro transcription of NS1 mRNA

Viral NS1 mRNA was prepared from an in-vitro transcription system. Total RNA was extracted from virus-infected cell lysates using the TRIzol-total RNA extraction kit (Invitrogen). The extracted RNA was eluted in 30 μL of nuclease-free water, and stored in aliquots at -80°C until used. In order to avoid contamination with genomic DNA, the extracted preparation was treated with DNA-Free DNase (Invitrogen). The quality of extracted RNA preparation was assessed by measuring optical density at 260/280 nm with the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). cDNA were reversely transcribed from RNA using the SuperScript™ III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). DNA fragments containing the coding region of the NS1 gene were linked to a T7 promoter sequence, with or without "hexa histidine-tag" and a polyA tail was created at the end of the fragment by PCR. The PCR was performed using the Platinum® Taq DNA polymerase high fidelity (Invitrogen). The primers used for the amplification are listed in Table 1. In-vitro transcription was performed using the mMESSAGE mMachine T7 Ultra kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) with 2 h incubation at 37°C. The mRNA was TURBO DNase treated for 15 min at 37°C. Polyadenylation was also performed. The mRNA products were then purified using the MEGAclear kit (Ambion). The quantity and quality of capped mRNA produced was analyzed by measuring optical density at 260/280 nm with the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies) and by denaturing gel electrophoresis.

Table 1.

Primers used for amplification of NS1 genes.

| Influenza subtypes | Primer sequences |

|---|---|

| H1N1/2002 | Forward: 5'- GATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGAGCAAAAGCAGGGTGGCAA-3' Reverse: 5'- TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTTTTATCATT-3' |

| 2009 pdmH1N1 | Forward: 5'- GGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGAGCAAAAGCAGGGTGACAA-3' Reverse: 5'- TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTTTTATCATT-3' |

| H2N2 | Forward: 5'- GGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGAGCAAAAGCAGGGTGACAA-3' Reverse: 5'- TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTTTTATCATT-3' |

| H3N2/2004 | Forward: 5'- GGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGAGCAAAAGCAGGGTGACAA-3' Reverse: 5'- TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTTTTATCATT-3' |

| H5N1/2004 | Forward: 5'- GGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGAGCAAAAGCAGGGTGACAAAG-3' Reverse: 5'- TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTAGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTTTTATCAT-3' |

| H7N3/2004 | Forward: 5'- GGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGAGCAAAAGCAGGGTGACAA-3' Reverse: 5'- TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTTTTATCATT-3' |

| H9N2/1997 | Forward: 5'- GGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGAGCAAAAGCAGGGTGACAA-3' Reverse: 5'- TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTTTTATCATT-3' |

Transient transfection system

Approximately 1 × 106 NCI-H292 cells were transfected with 4 μg of NS1 mRNA in a six-well plate using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen). Briefly, NS1 mRNA and Lipofectamine™ 2000 were incubated together for 30 min in 500 μL of Opti-MEM I before adding to the cells. The transfection efficiency was calculated from the percentage of fluorescent cells that were observed using florescence microscopy after the transfection of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled short nucleotide primers in separate controls. The transfection efficiency was about 70%. In another control, the effect of the transfection of synthetic double-stranded RNA polyriboinosinic polyribocytidylic acid [poly(I:C)] (Sigma, St Louis, MO), on cytokines/chemokines and apoptosis induction were also observed and took into account for the net effect of mRNA transfection of the experimental cells. The experimentally transfected cells were then collected at 3, 6, 18 and 24 h post-transfection; washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and trypsinized. After harvesting by centrifugation, the cells were resuspended in a small volume (200-400 μL) of PBS for propidium iodide (PI) staining and FITC-conjugated annexin V (Annexin V-FITC) staining of apoptotic cells.

Western blot analysis

The mRNA-transfected or non-transfected cell monolayers were lysed, and the total protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Proteins with equivalent concentration were heated for 5 min at 100°C in sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol, and were then resolved by 12% or 15% SDS-PAGE. The resolved proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) and blocked with 1% powdered milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) for 1 h at room temperature. Mouse or rabbit antibodies were then used to probe for His-tagged NS1 (Invitrogen), with overnight incubation at 4°C. The membrane was subsequently incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 1:1000 anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase-linked whole secondary antibody (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). The membrane was also probed for GAPDH as a loading control (Chemicon, Temecula, CA).

Quantification of cytokine/chemokine protein expression using cytometric bead array (CBA)

Cell culture supernatant was collected at 0, 3, 6, 18 and 24 h post-transfection for cytokine/chemokine measurement by the Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) Soluble Protein Flex Set system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) using the BD FACSAria Flow Cytometer System (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Six cytokines/chemokines (CCL-2/MCP-1, CCL-3/MIP-1α, CCL-5/RANTES, CXCL-9/MIG, CXCL-10/IP-10, IL-6) were measured. The results were expressed as number of fold changes with reference to the levels of non-transfected cell controls. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Propidium iodide (PI) staining and DNA content analysis by flow cytometry

The overall (early and late phases together) proportion of apoptotic cells was measured by PI flow cytometric assay which is based on the principle that apoptotic cells are characterized by DNA fragmentation and the consequent loss of nuclear DNA content at the late phase of apoptosis. Briefly, transfected cells (106) were washed with PBS and fixed with 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. The fixed cells were then stained with 50 μg/mL of PI (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with 1 μg of RNase A/mL at 4°C for 1 h. PI binds to DNA by intercalating between the bases, with no sequence preference. The DNA contents of the cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSAria; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells at the late phase of apoptosis, i.e., sub-G1 (hypodiploid) cells, will have DNA contents lower than those of G1 cells. The proportions of these apoptotic cells, i.e., sub-G1 cells, at different time points post-transfection were determined. Staurosporine-treated cells were also used as a positive control. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Annexin V-FITC staining of apoptotic cells and analysis by flow cytometry

Annexin V-FITC staining was used to measure the proportion of cells that were at the early phase of apoptosis. Cells were collected, washed with PBS, and stained with FITC-conjugated annexin V (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and PI for 20 min at room temperature in dark. The stained cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSAria; BD Biosciences). FITC-conjugated annexin V binds to surface phosphatidylserine translocated from the intra- to the extracellular plasma membrane early in apoptosis. Cells were simultaneously stained with PI to discriminate membrane-permeable necrotic cells from FITC-labeled apoptotic cells. Apoptotic cells were identified as those with annexin V-FITC staining only, and the results were expressed as the proportion of these cells among the total number of cells analyzed. Staurosporine-treated cells were also used as a positive control. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Results

Cytokine/chemokine expression profiles

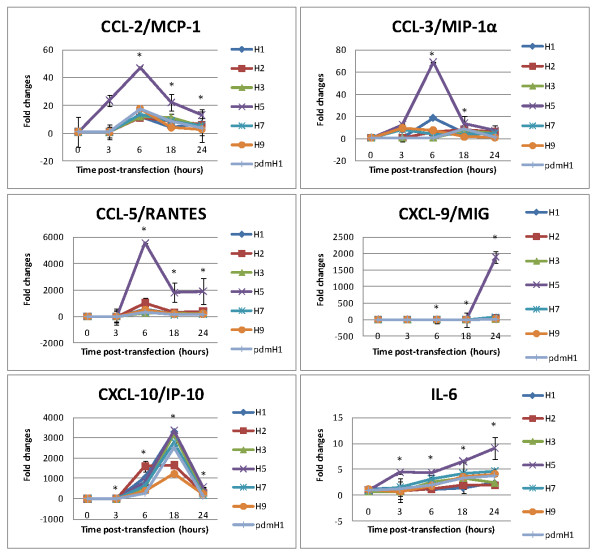

Different profiles of cytokine/chemokine expression were observed following the transfection of NS1 mRNA derived from various influenza subtypes (Figure 1). Overall, the most prominent induction was observed for CXCL-10/IP-10 regardless of influenza subtype, and with > 1,000-fold increase at peak induction. IL-6 was also induced by all subtypes but to a much lower extent (< 10-fold increase at peak induction). A distinct pattern in induction between H5 and other subtypes was observed for CCL-2/MCP-1, CCL-3/MIP-1α, CCL-5/RANTES and CXCL-9/MIG. For all these four cytokines/chemokines, the level of expression induced by H5 was much higher than other subtypes.

Figure 1.

Cytokines/chemokines induced by transfection of NS1 mRNA of different influenza subtypes. NCI-H292 cells were transfected with NS1 mRNA derived from seven subtypes of influenza A including seasonal H1N1 (H1), H2N2, H3N2, H5N1, H7N3, H9N2 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pdmH1). Cytokine/chemokine levels are expressed as fold-changes compared to the non-transfected cell controls ± SD (p* < 0.05) measured at the same time points.

The six studied cytokines/chemokines can be divided in to two groups according to the time to reach peak level of induction. The "early" group included CCL-2/MCP-1, CCL-3/MIP-1α and CCL-5/RANTES showing a peak at 6 h post-transfection. All members of the "early" group showed a strong response to H5, but they were only induced to low levels by other subtypes (Figure 1). The "late" group included IL-6, CXCL-9/MIG and CXCL-10/IP-10 showing a peak at 18-24 h post-transfection. No obvious correlation between the time to reach peak level and the subtype of virus was observed.

Among the seven subtypes of influenza examined, only H5 showed a distinct profile of cytokine/chemokine induction; and being the strongest inducer for all the six cytokines/chemokines. The cytokine/chemokine induction profiles observed for the recently emerged 2009 pdmH1N1-NS1 were similar to previous seasonal strains.

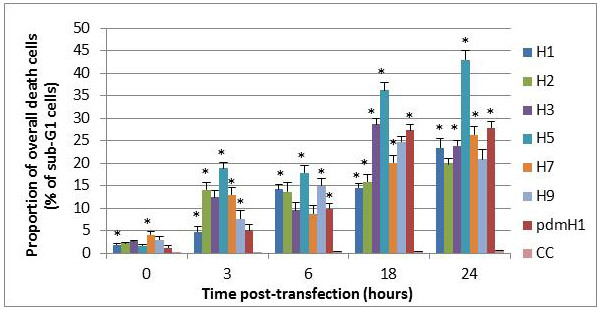

Apoptosis

The overall (early and late phases together) proportion of apoptotic cells for H5N1/2004-NS1 was the highest at all time points as compared to other subtypes (Figure 2). At 24 h post-transfection, 44% of H5N1-NS1-transfected cells had entered apoptosis, compared to 20-28% of other subtypes. The 2009 pdmH1N1-, H3N2-, and H9N2-transfected cells showed a relatively higher proportion of apoptosis (25-29%) at 18 h post-transfection; however these subtypes reached similar levels as compared to other non-H5 subtypes at 24 h post-transfection (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of overall apoptotic cells induced by transfection of NS1 mRNA of different influenza subtypes. NCI-H292 cells were transfected with NS1 mRNA derived from seven subtypes of influenza A including seasonal H1N1 (H1), H2N2, H3N2, H5N1, H7N3, H9N2 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pdmH1). CC represents non-transfected controls. The overall proportion of death cells was measured by propidium iodide staining using flow cytometry with the sub-G1 cell proportion counted ± SD (p* < 0.05).

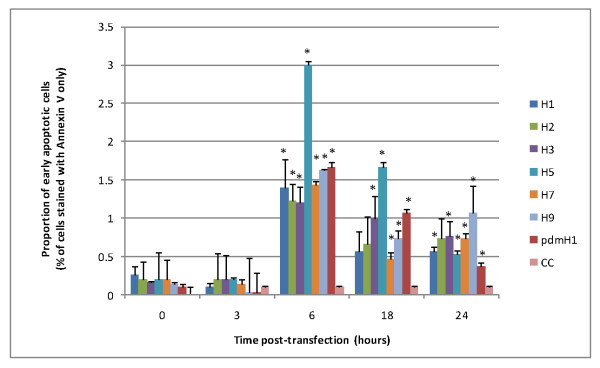

Figure 3 shows the proportion of cells at the early phase of apoptosis at different time points post-transfection. Overall, apoptotic activity was the highest at 6 h post-transfection, and then decreased gradually. This time course of apoptosis was similar among the different subtypes of influenza viruses examined. Figure 3 displays the distinct apoptotic induction ability of H5N1 as compared to other subtypes. At the peak of apoptotic activity (6 h post-transfection), the proportion of apoptotic cells for H5N1 was about twice higher than those for other subtypes. The newly emerged 2009 pdmH1N1-NS1 showed a moderate ability in inducing apoptosis. At both 6 h and 18 h post-transfection, the proportion of early apoptotic cells ranked second, just following H5N1/2004-NS1, among the subtypes examined.

Figure 3.

Proportion of early apoptotic cells induced by transfection of NS1 mRNA of different influenza subtypes. NCI-H292 cells were transfected with NS1 mRNA derived from seven subtypes of influenza A including seasonal H1N1 (H1), H2N2, H3N2, H5N1, H7N3, H9N2 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 (pdmH1). CC represents non-transfected controls. Cells at early apoptotic phase as stained positive for annexin V but not propidium iodide were identified by flow cytometry ± SD (p* < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, the pathogenic properties of NS1 proteins encoded by different subtypes of influenza A viruses were compared by measuring cytokine/chemokine expression and apoptosis induced in transfected cells.

While the key target of influenza virus is lung epithelial cells [48,49], most studies on influenza pathogenesis have been based on macrophages and monocytes infected in-vitro or in-vivo [50-52]. It is important to note that at the time of early infection these immune cells would not be present in great numbers until they have been recruited into the area. The mechanism concerning bronchial infiltration of inflammatory cells, particularly lymphocytes and eosinophils, and the subsequent hyperresponsiveness of the bronchial wall induced by viruses remain unclear [53]. Therefore, in this study we have used a cell line derived from human lung epithelial cells as an in-vitro model to study the pathogenicity of influenza NS1 proteins.

Previous in-vitro studies have shown that influenza infection induces the production of cytokines IFN-α, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8 and the mononuclear cell attractant chemokines CCL-3/MIP-1α, CCL-4/MIP-1β, CCL-2/MCP-1, CCL-7/MCP-3, CXCL-10/IP-10 and CCL-5/RANTES in human monocytes, epithelial cells, rat alveolar or murine macrophages [48,50,53-62]. Based on the findings of these studies, we identified the six key cytokines/chemokines for the current study.

Recently, it has been shown that the inflammatory response is played out over time in a reproducible and organized way with different induction kinetics after an initiating stimulus [63]. Cytokines released following infection can be classified broadly into "early" and "late" cytokines. Our results showed that CCL-2/MCP-1, CCL-3/MIP-1α and CCL-5/RANTES were produced early post-transfection; while IL-6, CXCL-10/IP-10 and CXCL-9/MIG were produced later. This time course of cytokine/chemokine production was consistently observed across different subtypes of influenza viruses with different pathogenicity. It would be worthwhile to further investigate whether this temporal sequence is unique to influenza or generally true for other acute respiratory viruses.

The most remarkable observation in this study was the distinct cytokine/chemokine profiles induced by the NS1 protein of H5N1. Our in-vitro observation is in line with previous reports that the peripheral blood of patients infected with H5N1 have much higher serum levels of CXCL-10/IP-10 and CCL-2/MCP-1 than patients infected with seasonal influenza [13,15]. Furthermore, the in-vitro model used in our study by measuring the levels of cytokines in lung tissue may be more relevant to pathogenesis than levels in blood [15]. Another in-vitro study in macrophages also showed a stronger cytokine induction by H5N1/1997 viruses compared to H3N2 [51].

We found that NS1 protein encoded by 2009 pdmH1N1 virus induced similar levels of cytokine/chemokine compared to seasonal H1N1 and H3N2 strains. This observation is in line with a recent report which showed that pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus-infected macrophages was similar to that of seasonal H1N1/1999, and was much lower than in H5N1/2004-infected cells [64-67].

In this study, we observed a similar temporal profile of apoptosis as induced by different subtypes of influenza. This is in contrast to previous studies based on whole virions. For instance, Geiler et al. (2011) [67] reported a delay in the induction of apoptosis for 2009 pdmH1N1 compared to H5N1; whereas Mok et al. (2007) [68] reported a delayed apoptosis of H5N1 compared to seasonal H1N1. The reason for these different observations remains to be verified. Both of these two studies [67,68] used whole virions, and therefore the observation may be partly related to the time required for sufficient virus replication and hence the synthesis of a certain amount of NS1 protein; whereas the current study used transfection where the same amount of NS1 was expected to be synthesized at any one time for different subtypes. If NS1 protein per se was the question of interest, using transfection methods with the same transfection efficiencies among different subtypes, might avoid biases result from differences in replication efficiency of the viruses being studied. Another major difference is that in contrast to the lung epithelial cells used in our study, the two previous studies used macrophages. These two cell types may display differences in apoptotic response to different subtypes of influenza.

Another remarkable observation of the current study is the high apoptosis inducing ability conferred by NS1 protein encoded by H5N1 compared to all other subtypes. This is reminiscent of the rapid development of severe primary pneumonitis in patients infected with H5N1 [4,13-16]. Our data showed that the apoptosis inducing ability of NS1 protein encoded by 2009 pdmH1N1 virus was similar to H7, H9 and seasonal subtypes; but much lower than H5N1. This is in line with a previous observation based on macrophages infected with whole virions, where the level of apoptosis induced by 2009 pdmH1N1 was much lower than H5N1 [67].

NS1 have both pro- and anti-apoptotic functions, and the level of apoptosis observed reflects a balance between the two [30,34,69-73]. It would be worthwhile to further investigate whether the NS1 encoded by H5N1 is more pro-apoptotic or less anti-apoptotic as compared to other subtypes.

Conclusions

This study confirms that transfection of human lung epithelial cell line with NS1 mRNA is a suitable in-vitro model to delineate and compare the function of NS1 proteins encoded by different influenza subtypes. Our data indicates that NS1 protein is one of the keys for an exceptional higher pathogenicity of H5N1 compared to other avian and human subtypes. The NS1 protein encoded by 2009 pdmH1N1 exhibits a similar pro-inflammatory and apoptosis inducing ability as with other human seasonal subtypes, reflecting their similarity in pathogenicity. It is worthwhile to further explore the potential of using NS1 protein as a target of therapeutic intervention.

Abbreviations

2009 pdmH1N1: 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus; Annexin V-FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated annexin V staining; BCA: bicinchoninic acid assay; CBA: Cytometric Bead Array; CCL-2/MCP-1: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2/monocyte chemotactic protein-1; CCL-3/MIP-1α: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3/Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α; CCL-4/MIP-1β: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3/Macrophage inflammatory protein-1β; CCL-5/RANTES: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5/Regulated upon Activation, Normal T-cell Expressed, and Secreted; CCL-7/MCP-3: Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2/monocyte chemotactic protein-3; cDNA: complementary Deoxyribonucleic Acid; CXCL-9/MIG: Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9/Monokine induced by gamma interferon; CXCL-10/IP-10: C-X-C motif chemokine 10/Interferon gamma-induced protein 10; FBS: fetal bovine serum; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HA: hemagglutinin; H1N1/2002: (A/HongKong/CUHK-13003/2002); H2N2: H2 subtype (A/Asia/57/3); H3N2/2004: (A/HongKong/CUHK-22910/2004); H5N1/2004: (A/Thai/KAN1/2004); H7N3/2004: (A/Canada/504/2004); H9N2: (A/Duck/Hong Kong/Y280/1997); IFN-α: Interferon alpha; IFN-β: Interferon beta; IgG: immunoglobulin G; IL-1: Interleukin 1; IL-6: Interleukin 6; IL-8: Interleukin 8; M1: matrix protein 1; M2: matrix protein 2; MDCK cells: Mandin-Darby canine kidney cells; mRNA: messenger Ribonucleic Acid; NA: neuraminidase; NP: nucleoprotein; NS1: non-structural protein 1; NS2: non-structural protein 2; PA: polymerase acidic protein; PB1: polymerase basic protein 1; PB2: polymerase basic protein 2; PBS: phosphate-buffered saline; PI staining: propidium iodide staining; PI3-kinase: phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; PKR: double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase; poly(I:C): polyriboinosinic polyribocytidylic acid; PVDF membrane: Polyvinylidene fluoride membrane; RIG-I: retinoic acid-inducible gene product I; RNaseL: 2-5A-dependent ribonuclease; RPMI-1640 medium: Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium; SDS-PAGE: sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; WHO: World Health Organization

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ACMY performed the in-vitro transcription assays, RT-PCR assays, apoptotic cells staining and flow-cytometry assays. WYL was responsible for experimental design, analyses and drafting of the manuscript. PKSC was responsible for design and supervision of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

WY Lam, Email: lamwaiyip@cuhk.edu.hk.

Apple CM Yeung, Email: appleyeung@gmail.com.

Paul KS Chan, Email: paulkschan@cuhk.edu.hk.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Pilaipan Puthavathana for provision of A/Thailand/1(KAN-1)/2004 (H5N1) isolate; Dr. Yan Li for provision of A/Canada/504/2004 (H7N3) isolate; Prof. Malik Peiris for provision of A/Duck/Hong Kong/Y280/1997 (H9N2) isolate and Dr. Ian G Barr for provision of the pandemic H1N1 viral RNA (A/Auckland/1/2009). This study was supported by the Research Fund for the Control of Infectious Diseases, Food and Health Bureau, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Project code: CU-09-01-04-Lab-3).

References

- Claas EC, Osterhaus AD, van Beek R, De Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Senne DA, Krauss S, Shortridge KF, Webster RG. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Lancet. 1998;351:472–477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen KY, Chan PK, Peiris M, Tsang DN, Que TL, Shortridge KF, Cheung PT, To WK, Ho ET, Sung R. et al. Clinical features and rapid viral diagnosis of human disease associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. Lancet. 1998;351:467–471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris M, Yuen KY, Leung CW, Chan KH, Ip PL, Lai RW, Orr WK, Shortridge KF. Human infection with influenza H9N2. Lancet. 1999;354:916–917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To KF, Chan PK, Chan KF, Lee WK, Lam WY, Wong KF, Tang NL, Tsang DN, Sung RY, Buckley TA. et al. Pathology of fatal human infection associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. J Med Virol. 2001;63:242–246. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200103)63:3<242::AID-JMV1007>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PK. Outbreak of avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in Hong Kong in 1997. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(Suppl 2):S58–S64. doi: 10.1086/338820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier RA, Schneeberger PM, Rozendaal FW, Broekman JM, Kemink SA, Munster V, Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Schutten M, Van Doornum GJ. et al. Avian influenza A virus (H7N7) associated with human conjunctivitis and a fatal case of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1356–1361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308352100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Suzuki Y, Suzuki T, Le MQ, Nidom CA, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Muramoto Y, Ito M, Kiso M, Horimoto T. et al. Haemagglutinin mutations responsible for the binding of H5N1 influenza A viruses to human-type receptors. Nature. 2006;444:378–382. doi: 10.1038/nature05264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Ghafar AN, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, Hayden FG, Nguyen DH, de Jong MD, Naghdaliyev A, Peiris JS, Shindo N, Soeroso S. et al. Update on avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in humans. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:261–273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A/(H5N1) reported to WHO. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; 2011. http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/EN_GIP_20111215CumulativeNumberH5N1cases.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: influenza activity-United States, August 30, 2009-March 27, 2010, and composition of the 2010-11 influenza vaccine. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:423–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, Harper SA, Shaw M, Uyeki TM, Zaki SR, Hayden FG, Hui DS, Kettner JD. et al. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1708–1719. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Chan PK, Wong CK, Wong KT, Choi KW, Joynt GM, Lam P, Chan MC, Wong BC, Lui GC, Sin WW, Wong RY, Lam WY, Yeung AC, Leung TF, So HY, Yu AW, Sung JJ, Hui DS. Viral clearance and inflammatory response patterns in adults hospitalized for pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus pneumonia. Antivir Ther. 2011;16::237–47. doi: 10.3851/IMP1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris JS, Yu WC, Leung CW, Cheung CY, Ng WF, Nicholls JM, Ng TK, Chan KH, Lai ST, Lim WL. et al. Re-emergence of fatal human influenza A subtype H5N1 disease. Lancet. 2004;363:617–619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15595-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MD, Hien TT. Avian influenza A (H5N1) J Clin Virol. 2006;35:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MD, Simmons CP, Thanh TT, Hien VM, Smith GJ, Chau TN, Hoang DM, Chau NV, Khanh TH, Dong VC. et al. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat Med. 2006;12:1203–1207. doi: 10.1038/nm1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MD. H5N1 transmission and disease: observations from the frontlines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:S54–S56. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181684d2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydon EW, Morris SJ, Sweet C. Role of apoptosis and cytokines in influenza virus morbidity. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:837–850. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korteweg C, Gu J. Pathology, molecular biology, and pathogenesis of avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1155–1170. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M, Gao P, Halfmann P, Kawaoka Y. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science. 2001;293:1840–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1062882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiss GK, Salvatore M, Tumpey TM, Carter VS, Wang X, Basler CF, Taubenberger JK, Bumgarner RE, Palese P, Katze MG. et al. Cellular transcriptional profiling in influenza A virus-infected lung epithelial cells: the role of the nonstructural NS1 protein in the evasion of the host innate defense and its potential contribution to pandemic influenza. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10736–10741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112338099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumpey TM, Garcia-Sastre A, Taubenberger JK, Palese P, Swayne DE, Basler CF. Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3166–3171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308391100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser L, Stevens J, Zamarin D, Wilson IA, Garcia-Sastre A, Tumpey TM, Basler CF, Taubenberger JK, Palese P. A single amino acid substitution in 1918 influenza virus hemagglutinin changes receptor binding specificity. J Virol. 2005;79:11533–11536. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11533-11536.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumpey TM, Basler CF, Aguilar PV, Zeng H, Solorzano A, Swayne DE, Cox NJ, Katz JM, Taubenberger JK, Palese P. et al. Characterization of the reconstructed 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic virus. Science. 2005;310:77–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1119392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kash JC, Tumpey TM, Proll SC, Carter V, Perwitasari O, Thomas MJ, Basler CF, Palese P, Taubenberger JK, Garcia-Sastre A. et al. Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2006;443:578–581. doi: 10.1038/nature05181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubenberger JK. The origin and virulence of the 1918 "Spanish" influenza virus. Proc Am Philos Soc. 2006;150:86–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamarin D, Ortigoza MB, Palese P. Influenza A virus PB1-F2 protein contributes to viral pathogenesis in mice. J Virol. 2006;80:7976–7983. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00415-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Bright RA, Subbarao K, Smith C, Cox NJ, Katz JM, Matsuoka Y. Polygenic virulence factors involved in pathogenesis of 1997 Hong Kong H5N1 influenza viruses in mice. Virus Res. 2007;128:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M, Hatta Y, Kim JH, Watanabe S, Shinya K, Nguyen T, Lien PS, Le QM, Kawaoka Y. Growth of H5N1 influenza A viruses in the upper respiratory tracts of mice. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1374–1379. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreede FT, Jung TE, Brownlee GG. Model suggesting that replication of influenza virus is regulated by stabilization of replicative intermediates. J Virol. 2004;78:9568–9572. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9568-9572.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon AM, Marion RM, Zurcher T, Gomez P, Portela A, Nieto A, Ortin J. Defective RNA replication and late gene expression in temperature-sensitive influenza viruses expressing deleted forms of the NS1 protein. J Virol. 2004;78:3880–3888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.3880-3888.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min JY, Li S, Sen GC, Krug RM. A site on the influenza A virus NS1 protein mediates both inhibition of PKR activation and temporal regulation of viral RNA synthesis. Virology. 2007;363:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale BG, Jackson D, Chen YH, Lamb RA, Randall RE. Influenza A virus NS1 protein binds p85beta and activates phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14194–14199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606109103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt C, Wolff T, Pleschka S, Planz O, Beermann W, Bode JG, Schmolke M, Ludwig S. Influenza A virus NS1 protein activates the PI3K/Akt pathway to mediate antiapoptotic signaling responses. J Virol. 2007;81:3058–3067. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02082-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin YK, Liu Q, Tikoo SK, Babiuk LA, Zhou Y. Influenza A virus NS1 protein activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway by direct interaction with the p85 subunit of PI3K. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:13–18. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhirnov OP, Klenk HD. Control of apoptosis in influenza virus-infected cells by up-regulation of Akt and p53 signaling. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1419–1432. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0071-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min JY, Krug RM. The primary function of RNA binding by the influenza A virus NS1 protein in infected cells: Inhibiting the 2'-5' oligo (A) synthetase/RNase L pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7100–7105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602184103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talon J, Horvath CM, Polley R, Basler CF, Muster T, Palese P, Garcia-Sastre A. Activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 is inhibited by the influenza A virus NS1 protein. J Virol. 2000;74:7989–7996. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.17.7989-7996.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Li M, Zheng H, Muster T, Palese P, Beg AA, Garcia-Sastre A. Influenza A virus NS1 protein prevents activation of NF-kappaB and induction of alpha/beta interferon. J Virol. 2000;74:11566–11573. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.24.11566-11573.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig S, Wang X, Ehrhardt C, Zheng H, Donelan N, Planz O, Pleschka S, Garcia-Sastre A, Heins G, Wolff T. The influenza A virus NS1 protein inhibits activation of Jun N-terminal kinase and AP-1 transcription factors. J Virol. 2002;76:11166–11171. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11166-11171.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Chen LM, Zeng H, Gomez JA, Plowden J, Fujita T, Katz JM, Donis RO, Sambhara S. NS1 protein of influenza A virus inhibits the function of intracytoplasmic pathogen sensor, RIG-I. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:263–269. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0283RC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mibayashi M, Martinez-Sobrido L, Loo YM, Cardenas WB, Gale M, Garcia-Sastre A. Inhibition of retinoic acid-inducible gene I-mediated induction of beta interferon by the NS1 protein of influenza A virus. J Virol. 2007;81:514–524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01265-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz B, Rejaibi A, Dauber B, Eckhard J, Vinzing M, Schmeck B, Hippenstiel S, Suttorp N, Wolff T. IFNbeta induction by influenza A virus is mediated by RIG-I which is regulated by the viral NS1 protein. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:930–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff ME, Barabino SM, Li Y, Keller W, Krug RM. Influenza virus NS1 protein interacts with the cellular 30 kDa subunit of CPSF and inhibits 3'end formation of cellular pre-mRNAs. Mol Cell. 1998;1:991–1000. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noah DL, Twu KY, Krug RM. Cellular antiviral responses against influenza A virus are countered at the posttranscriptional level by the viral NS1A protein via its binding to a cellular protein required for the 3' end processing of cellular pre-mRNAS. Virology. 2003;307:386–395. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(02)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann M, Garcia-Sastre A, Carnero E, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, Palese P, Muster T. Influenza virus NS1 protein counteracts PKR-mediated inhibition of replication. J Virol. 2000;74:6203–6206. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.13.6203-6206.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, Hossain MJ, Hickman D, Perez DR, Lamb RA. A new influenza virus virulence determinant: the NS1 protein four C-terminal residues modulate pathogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4381–4386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800482105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Sesma A, Marukian S, Ebersole BJ, Kaminski D, Park MS, Yuen T, Sealfon SC, Garcia-Sastre A, Moran TM. Influenza virus evades innate and adaptive immunity via the NS1 protein. J Virol. 2006;80:6295–6304. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02381-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukura S, Kokubu F, Noda H, Tokunaga H, Adachi M. Expression of IL-6, IL-8, and RANTES on human bronchial epithelial cells, NCI-H292, induced by influenza virus A. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:1080–1087. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(96)80195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo SH, Webster RG. Tumor necrosis factor alpha exerts powerful anti-influenza virus effects in lung epithelial cells. J Virol. 2002;76:1071–1076. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1071-1076.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann P, Sprenger H, Kaufmann A, Bender A, Hasse C, Nain M, Gemsa D. Susceptibility of mononuclear phagocytes to influenza A virus infection and possible role in the antiviral response. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:408–414. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.4.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CY, Poon LL, Lau AS, Luk W, Lau YL, Shortridge KF, Gordon S, Guan Y, Peiris JS. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human macrophages by influenza A (H5N1) viruses: a mechanism for the unusual severity of human disease? Lancet. 2002;360:1831–1837. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KP, Lee SM, Cheung CY, Ng IH, Poon LL, Guan Y, Ip NY, Lau AS, Peiris JS. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in primary human macrophages by influenza A virus (H5N1) is selectively regulated by IFN regulatory factor 3 and p38 MAPK. J Immunol. 2009;182:1088–1098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi M, Matsukura S, Tokunaga H, Kokubu F. Expression of cytokines on human bronchial epithelial cells induced by influenza virus A. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;113:307–311. doi: 10.1159/000237584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nain M, Hinder F, Gong JH, Schmidt A, Bender A, Sprenger H, Gemsa D. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha production of influenza A virus-infected macrophages and potentiating effect of lipopolysaccharides. J Immunol. 1990;145:1921–1928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi AM, Jacoby DB. Influenza virus A infection induces interleukin-8 gene expression in human airway epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1992;309:327–329. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80799-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussfeld D, Kaufmann A, Meyer RG, Gemsa D, Sprenger H. Differential mononuclear leukocyte attracting chemokine production after stimulation with active and inactivated influenza A virus. Cell Immunol. 1998;186:1–7. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukura S, Kokubu F, Kubo H, Tomita T, Tokunaga H, Kadokura M, Yamamoto T, Kuroiwa Y, Ohno T, Suzaki H. et al. Expression of RANTES by normal airway epithelial cells after influenza virus A infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;18:255–264. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.2.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julkunen I, Melen K, Nyqvist M, Pirhonen J, Sareneva T, Matikainen S. Inflammatory responses in influenza A virus infection. Vaccine. 2000;19(Suppl 1):S32–S37. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matikainen S, Pirhonen J, Miettinen M, Lehtonen A, Govenius-Vintola C, Sareneva T, Julkunen I. Influenza A and sendai viruses induce differential chemokine gene expression and transcription factor activation in human macrophages. Virology. 2000;276:138–147. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julkunen I, Sareneva T, Pirhonen J, Ronni T, Melen K, Matikainen S. Molecular pathogenesis of influenza A virus infection and virus-induced regulation of cytokine gene expression. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12:171–180. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(00)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydon EW, Smith H, Sweet C. Influenza A virus-induced apoptosis in bronchiolar epithelial (NCI-H292) cells limits pro-inflammatory cytokine release. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2389–2400. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18913-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam WY, Yeung AC, Chu IM, Chan PK. Profiles of cytokine and chemokine gene expression in human pulmonary epithelial cells induced by human and avian influenza viruses. Virol J. 2010;7:344. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S, Baltimore D. The stability of mRNA influences the temporal order of the induction of genes encoding inflammatory molecules. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:281–288. doi: 10.1038/ni.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RW, Yuen KM, Yu WC, Ho CC, Nicholls JM, Peiris JS, Chan MC. Influenza H5N1 and H1N1 virus replication and innate immune responses in bronchial epithelial cells are influenced by the state of differentiation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund P, Pirhonen J, Ikonen N, Ronkko E, Strengell M, Makela SM, Broman M, Hamming OJ, Hartmann R, Ziegler T. et al. Pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza A virus induces weak cytokine responses in human macrophages and dendritic cells and is highly sensitive to the antiviral actions of interferons. J Virol. 2010;84:1414–1422. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01619-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo PC, Tung ET, Chan KH, Lau CC, Lau SK, Yuen KY. Cytokine profiles induced by the novel swine-origin influenza A/H1N1 virus: implications for treatment strategies. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:346–353. doi: 10.1086/649785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiler J, Michaelis M, Sithisarn P, Cinatl J Jr. Comparison of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and cellular signal transduction in human macrophages infected with different influenza A viruses. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2011;200:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s00430-010-0173-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok CK, Lee DC, Cheung CY, Peiris M, Lau AS. Differential onset of apoptosis in influenza A virus. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:1275–1280. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82423-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-Cherry S, Dybdahl-Sissoko N, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Hinshaw VS. Influenza virus ns1 protein induces apoptosis in cultured cells. J Virol. 2001;75:7875–7881. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.7875-7881.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhirnov OP, Konakova TE, Wolff T, Klenk HD. NS1 protein of influenza A virus down-regulates apoptosis. J Virol. 2002;76:1617–1625. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1617-1625.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasakova J, Ferko B, Kittel C, Sereinig S, Romanova J, Katinger H, Egorov A. Influenza A mutant viruses with altered NS1 protein function provoke caspase-1 activation in primary human macrophages, resulting in fast apoptosis and release of high levels of interleukins 1beta and 18. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:185–195. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale BG, Randall RE, Ortin J, Jackson D. The multifunctional NS1 protein of influenza A viruses. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2359–2376. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/004606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam WY, Tang JW, Yeung AC, Chiu LC, Sung JJ, Chan PK. Avian influenza virus A/HK/483/97(H5N1) NS1 protein induces apoptosis in human airway epithelial cells. J Virol. 2008;82:2741–2751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01712-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]