Abstract

The polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3), important second messengers in brain, are released from membrane phospholipid following receptor-mediated activation of specific phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzymes. We developed an in vivo method in rodents using quantitative autoradiography to image PUFA incorporation into brain from plasma, and showed that their incorporation rates equal their rates of metabolic consumption by brain. Thus, quantitative imaging of unesterified plasma AA or DHA incorporation into brain can be used as a biomarker of brain PUFA metabolism and neurotransmission. We have employed our method to image and quantify effects of mood stabilizers on brain AA/DHA incorporation during neurotransmission by muscarinic M1,3,5, serotonergic 5-HT2A/2C, dopaminergic D2-like (D2, D3, D4) or glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors, and effects of inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, of selective serotonin and dopamine reuptake transporter inhibitors, of neuroinflammation (HIV-1 and lipopolysaccharide) and excitotoxicity, and in genetically modified rodents. The method has been extended for the use with positron emission tomography (PET), and can be employed to determine how human brain AA/DHA signaling and consumption are influenced by diet, aging, disease and genetics.

Keywords: arachidonic acid, bipolar disorder, brain imaging, docosahexaenoic acid, mood stabilizers, neuroinflammation

1. Introduction

Phospholipids and their component fatty acids play critical and dynamic roles in brain development, aging and disease (Horrocks and Farooqui, 2004; Rapoport, 2008). They participate in signal transduction, synaptic membrane remodeling, gene transcription and brain blood flow, and they modulate the brain's responses to drugs, neuroinflammation and ischemia. Brain phospholipid and fatty acid metabolism are abnormal in a number of human brain diseases, including stroke and vascular dementia, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, multiple sclerosis, HIV-1 associated dementia, bipolar disorder (BD), and depression. Thus, having a method to quantify and image different aspects of their metabolism in animal or human brain could elucidate and localize the active roles of lipids in health and disease.

Despite growing in vitro evidence that phospholipids and their components participate in multiple dynamic brain processes, important kinetic and energy-demanding aspects of this participation involving in vivo postsynaptic signaling frequently were misunderstood or ignored (Purdon and Rapoport, 2007). Current in vivo neuroimaging methods can quantify regional neuroreceptor densities, neurotransmitter synthesis, and parameters of energy metabolism such as regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) and regional cerebral metabolic rates for glucose (rCMRglc), but largely ignore neuroreceptor-initiated signal transduction. This has limited our understanding of how and where acutely or chronically administered drugs act in the brain, how these drugs modulate behavior and cognition, and how age, disease, genetic or dietary factors influence their signaling effects. Furthermore, it has only been since about 1988 (Axelrod et al., 1988) that pharmacologists began to realize that, like phospholipase C and adenylate cyclase, phospholipase A2 (PLA2, EC 3.1.1.4) is a major effector enzyme coupled to neuroreceptors by G-proteins to initiate arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6) or docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) release as a second messenger. Nevertheless, a major neuropharmacology text (Cooper et al., 2003) has largely ignored drug or functionally induced PLA2 signaling.

To overcome these limitations, we have elaborated a new "neuroimaging pharmacology of in vivo signal transduction" by: (1) identifying in unanesthetized rodents which neuroreceptors, reported from in vitro studies to be coupled to PLA2 and AA or DHA release by a G-protein or by allowing Ca2+ into the cell, can be activated or modified in response to an acute dose of an appropriate agonist, antagonist or response modifier; (2) relating patterns of activation to neural networks, behavioral changes and reported patterns of altered rCBF and rCMRglc; (3) imaging neuroplastic (long-term) effects on AA signaling by chronically administered centrally active drugs, as many drugs are clinically effective after chronic but not acute administration; (4) seeing how such neuroreceptor signaling is altered in disease or genetic rodent models; (5) translating our animal observations to generate clinical imaging protocols with positron emission tomography (PET).

2. Receptors coupled to phospholipase A2 enzymes

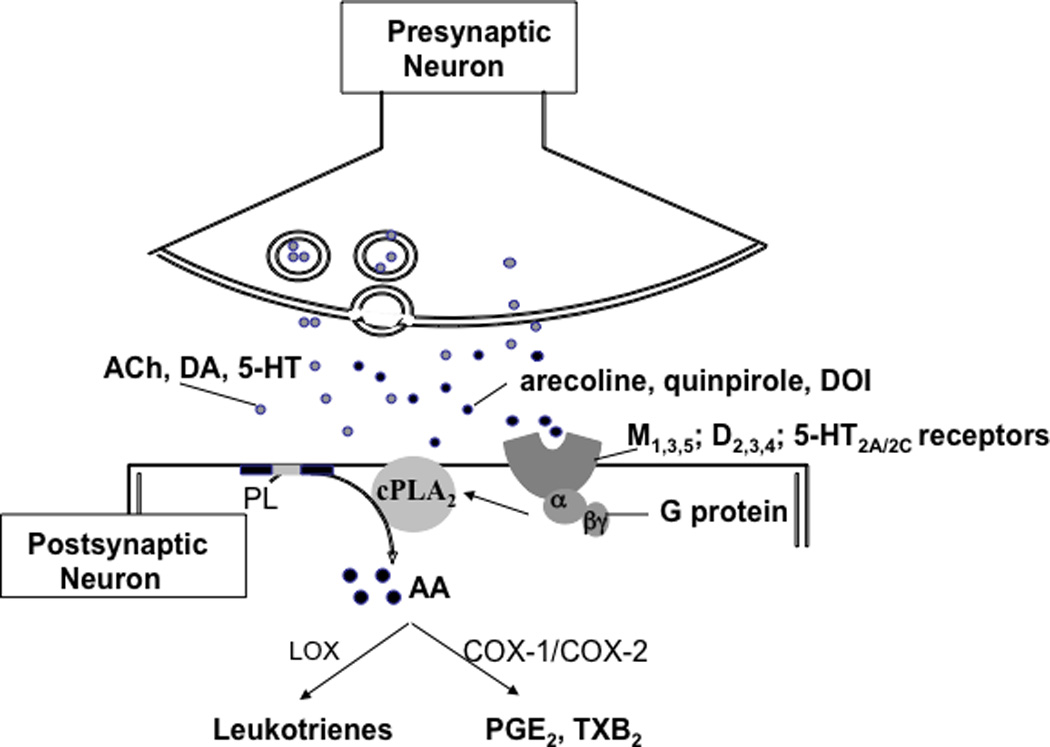

2.1 Receptors coupled to PLA2 by G-proteins

Agonist binding to specific neuroreceptors can activate a PLA2 to release the second messenger AA or DHA from the stereospecifically numbered sn-2 position of brain membrane phospholipid. Receptors that are coupled to a PLA2 to release AA via G-proteins include cholinergic muscarinic M1,3,5 receptors, dopaminergic D2-like receptors and serotonergic 5-HT2A/2C receptors (Bayon et al., 1997; Felder et al., 1990; Vial and Piomelli, 1995) (Figure 1), bradykinin β2 and adrenergic β2 receptors (Pavoine et al., 1999; Prado et al., 2002). Additionally, AA can be released via coupling to cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) receptors on astrocytes (Dinarello, 2002). DHA can be released following agonist activation of serotonergic 5-HT2A/2C, bradykinin B2, or purigenic P2Y receptors glial cells in vitro (Garcia and Kim, 1997; Strokin et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

Model explaining PLA2 activation and arachidonic acid signaling in response to muscarinic, dopaminergic, or serotonergic drugs. Activation of M1,3,5, D2-like (D2, D3, D4), 5-HT2A/2C receptors by acetylcholine (ACh), dopamine (DA) or serotonin (5-HT), or an appropriate agonist, arecoline, quinpirole or DOI, activates G protein and stimulates cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) thereby initiating rapid release of arachidonic acid (AA) from membrane phospholipid (PL). Then AA is converted to eicosanoids such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and thromboxane B2 (TXB2) via cyclooxygenases (COX).

There are four major classes of PLA2 enzymes in the rodent brain: AA-selective cytosolic Ca2+-dependent cPLA2 (85 kDa, Type IVA, cPLA2α), AA or DHA releasing secretory sPLA2, DHA-selective Ca2+-independent PLA2 (iPLA2, 85–88 kDa, Type VIA and VIB, or β and γ, respectively) and the Ca2+-independent plasmalogen-selective PLA2 (39 kDa, PlsEtn-PLA2) (Burke and Dennis, 2009; Strokin et al., 2007). All have been identified in astrocytes and neurons (Kishimoto et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999; Yegin et al., 2002). cPLA2 has been localized at postsynaptic neuronal membranes in brain (Ong et al., 1999; Pardue et al., 2003), requires a low concentration of Ca2+ (0.3 - 1 µM), in the physiological range of intracellular Ca2+ during neuronal activation (Ismailov et al., 2004), for its translocation to the membrane followed by phosphorylation and activation, and is selective for AA during acute stimulation of cells by diverse agents in vitro (Clark et al., 1995). sPLA2, which requires millimolar Ca2+ concentrations for activation, releases AA and DHA in vitro (Dennis, 1994), and is localized in presynaptic vesicles that are released by exocytosis during membrane depolarization (Wei et al., 2003). iPLA2 does not require Ca2+ for activation in vitro (Yang et al., 1999), and is selective for DHA in isolated glial cells and in the test tube (Strokin et al., 2003).

The released AA and its bioactive eicosanoid metabolites play important roles in neural functions including membrane excitability, gene transcription, apoptosis, cerebral blood flow, spatial learning and synaptic plasticity, resolution of inflammation, sleep and behavior (Huang et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2005; Serhan, 1997; Shimizu and Wolfe, 1990). Released DHA and its docosanoid metabolites produce antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects in brain tissue (Serhan et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2011).

Our in vivo fatty acid method is based on evidence that the major fraction of the AA or DHA that is released from synaptic membrane phospholipids by drug-induced, neuroreceptor-mediated PLA2 activation is rapidly reincorporated into brain phospholipids (Rapoport, 2001; Robinson et al., 1992), whereas a smaller fraction (about 4%) is metabolized by cyclooxygenases (COX), cytochrome P450 epoxygenases or lipoxygenases (LOX), to eicosanoids or docosanoids [e.g. prostanoids, electrophilic oxo-derivatives, maresins, resolvins, docosatrienes, and neuroprotectins], or to isoprostanes/neuroprostanes, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal/hexenal by non-enzymatic oxidation reactions (Groeger et al., 2010; Long and Picklo, 2010; Phillis et al., 2006; Serhan, 2009), or through β-oxidation (Gavino and Gavino, 1991). Unesterified AA or DHA in plasma rapidly and stoichiometrically replaces the quantity lost (Purdon et al., 1997; Rapoport, 2003; Rapoport, 2005), as AA and DHA are nutritionally essential and cannot be synthesized de novo from 2-carbon fragments, nor elongated significantly (< 1% for AA, < 0.1% for DHA) in brain from their respective nutritionally essential shorter-chain polyunsaturated precursors, linoleic (LA, 18:2n-6) and α-linolenic (α-LNA, 18:3n-3) acid (DeMar et al., 2005; DeMar et al., 2006a).

Injecting radiolabeled AA or DHA intravenously, and then measuring regional brain radioactivity using quantitative autoradiography can be used to determine the rate of AA or DHA replacement. A regional incorporation coefficient k* (regional brain radioactivity/integrated plasma radioactivity), calculated in this way, is independent of changes in rCBF (Chang et al., 1997), and represents the plasma-derived AA or DHA re-incorporated into brain phospholipids (Rapoport, 2003; Rapoport, 2005). The rate of incorporation, Jin, the product of k* and the plasma concentration of unlabeled unesterified AA or DHA equals the net rate of loss since neither polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) can be synthesized de novo in vertebrates (DeMar et al., 2005; DeMar et al., 2006a; Holman, 1986; Rapoport, 2003).

Regional incorporation coefficients k* (ml of plasma/s/g brain) of AA or DHA are calculated as (Robinson et al., 1992),

| (Eq. 1) |

c*plasma equals plasma radioactivity determined by scintillation counting (nCi/ml), c*brain equals brain radioactivity (nCi/g wet weight brain), and t equals time (min) after beginning of tracer AA or DHA infusion. Integrals of plasma radioactivity (input function in denominator) can be determined in each experiment by trapezoidal integration, and divided into c*brain to calculate k* for each experiment.

Regional rates of incorporation of unesterified AA or DHA from plasma into brain phospholipids, Jin (nmol/s/g) are calculated as follows, where cplasma is the unlabeled unesterified plasma PUFA concentration (nmol/ml),

| (Eq. 2) |

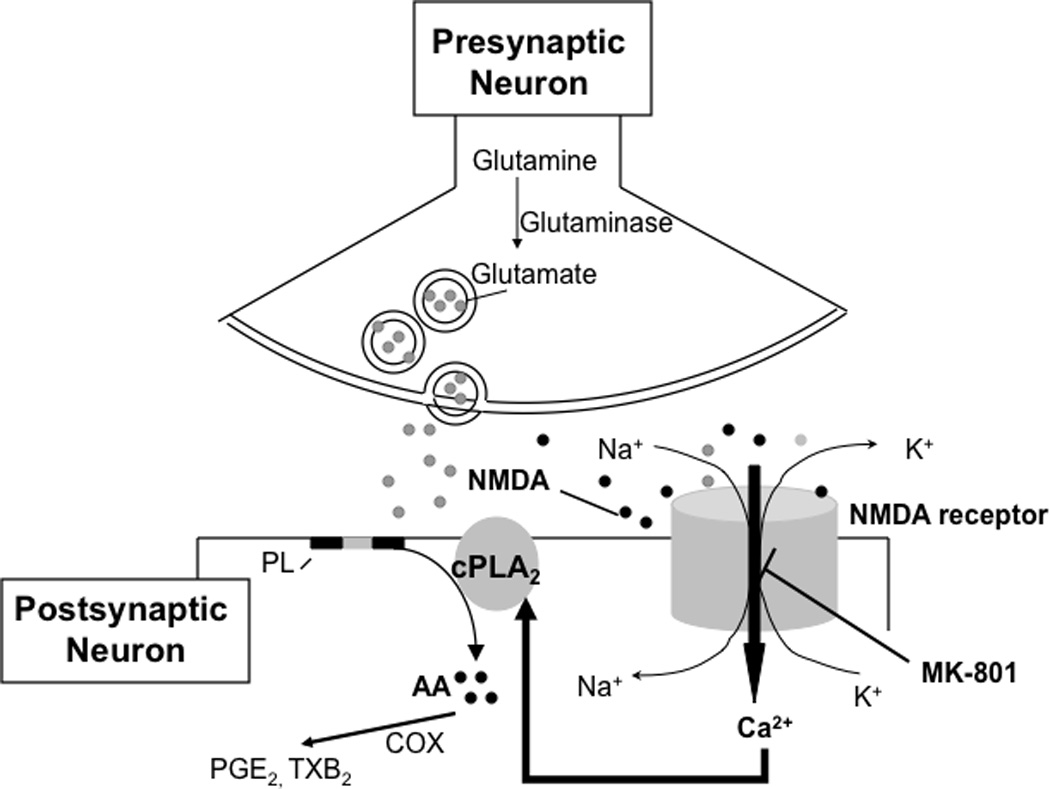

2.2 Calcium-initiated AA signaling via ionotropic receptors

In vitro evidence indicates that activation of ionotropic glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors (NMDARs) or of cholinergic nicotinic receptors, both of which are highly permeable to Ca2+ and are found mainly at postsynaptic and presynaptic terminals, respectively (Burnashev et al., 1995; Gotti et al., 2006; Petralia et al., 1994), can activate Ca2+-dependent cPLA2 and sPLA2 but not iPLA2 to release AA from membrane phospholipids, by allowing extracellular Ca2+ into the cell (Dumuis et al., 1988; Lazarewicz et al., 1988; Ramadan et al., 2010; Shen et al., 2007) (Figure 2). Although cPLA2 signaling via G-protein coupled receptors was identified as a priority for understanding brain function (Axelrod, 1995) (see above), in vivo cPLA2 signaling via NMDARs was not broached until our recent studies. Neurotransmission via these receptors can be aberrant in schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and BD (Beneyto et al., 2007; Inzelberg et al., 2006; Jacob et al., 2007; Palomino et al., 2007; Rao et al., 2010).

Figure 2.

Model explaining PLA2 activation and AA signaling in response to NMDA. Activation of glutamatergic NMDA receptors by glutamate or an appropriate agonist, NMDA, gates a cation channel that is permeable to Ca2+ and Na+. Influx of Ca2+ stimulates cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), thereby initiating rapid release of arachidonic acid (AA) from membrane phospholipid (PL). Then AA is converted to eicosanoids such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and thromboxane B2 (TXB2) via cyclooxygenases (COX). The NMDA receptor channel is blocked by the selective non-competitive NMDA antagonist, MK-801.

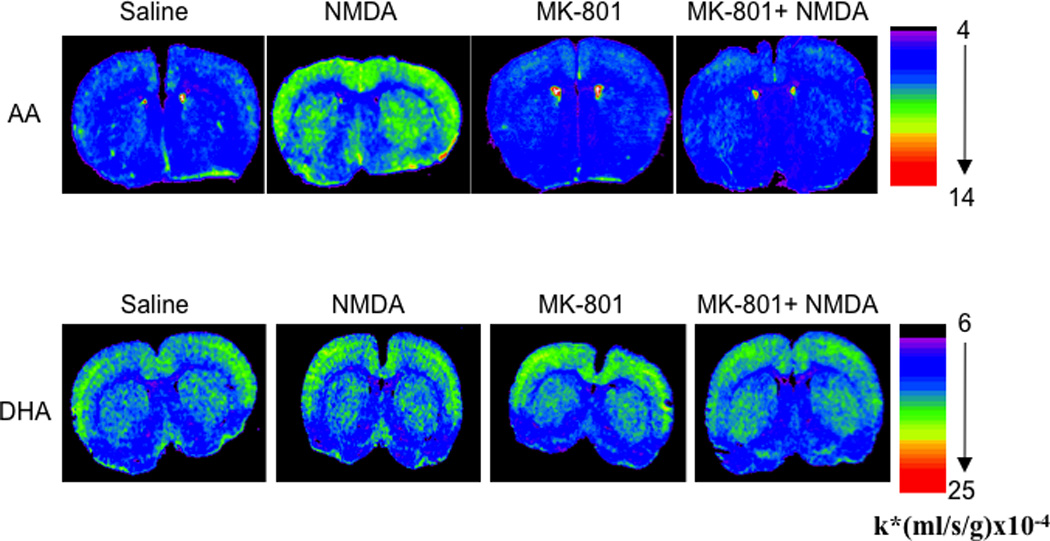

2.2.1 Imaging the acute NMDA initiated signal

With our in vivo fatty acid method, we imaged statistically significant increments in k* for AA in awake rats given subconvulsant NMDA doses (25 and 50 mg/kg, i.p.), an amino acid derivative which acts as a specific agonist at the NMDARs, in brain regions having high NMDAR densities such as the neocortex, hippocampus, caudate putamen, thalamus, substantia nigra, and nucleus accumbens (Basselin et al., 2006a; Basselin et al., 2007a; Basselin et al., 2008a; Basselin et al., 2008b; Ramadan et al., 2011a) (Figure 3). The increases could be blocked by pretreatment with the selective noncompetitive NMDAR antagonist dizocilpine (MK-801; 0.3 mg/kg i.p.) (Basselin et al., 2006a). Furthermore, reduction by MK-801 of baseline k* for AA by 16–49% suggested that NMDA-initiated PLA2 activation contributes substantially to the baseline release of AA in control-diet brain. This interpretation is consistent with evidence that glutamate receptors constitute about 75% of synapses in mammalian cerebral cortex, and that many of these synapses contain NMDARs (Fonnum, 1984; Hertz, 2006). As excessive glutamate release and receptor activation can contribute to cell damage in excitotoxicity, ischemia and neuroinflammation (Chang et al., 2008; Oechmichen and Meissner, 2006), our data showed that we can use AA imaging to follow these processes in animal models as well as in human disease.

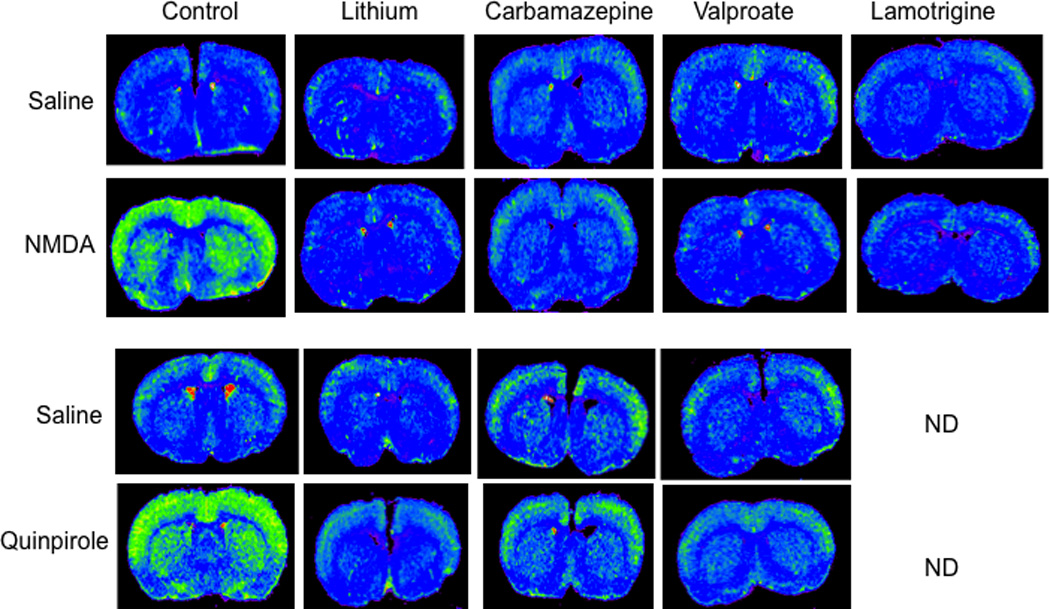

Figure 3.

Coronal autoradiographs of brain showing effects of NMDA (25 mg/kg, i.p.) and MK-801 (0.3 mg/kg, s.c.) on regional [1-14C] arachidonic acid and [1-14C] docosahexaenoic acid incorporation coefficients k* in rats. Values of k* are given on a color scale. AA, arachidonic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate. From (Basselin et al., 2006a; Ramadan et al., 2011b).

NMDA (25 mg/kg) or MK-801 compared to saline did not alter k* for DHA in any of 81 brain regions examined (Figure 3) (Ramadan et al., 2010; Rapoport et al., 2011), demonstrating that in vivo brain DHA but not AA signaling via NMDARs is independent of extracellular Ca2+ and of cPLA2 (Rosa and Rapoport, 2009). This is consistent with in vitro evidence that DHA hydrolysis can be mediated by iPLA2, PlsEtn-PLA2 or cPLA2γ, none of which requires extracellular Ca2+. However, DHA hydrolysis may be mediated by iPLA2 secondary to the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and interaction with calmodulin (Rosa and Rapoport, 2009).

2.2.2 Imaging the acute nicotine signal

Nicotine can improve memory and attention, but is highly addictive. It binds primarily to high affinity cholinergic α4β2 nicotinic receptors in brain, which modulate release of other neurotransmitters that activate post-synaptic G protein-coupled receptors coupled to cPLA2. α4β2 can undergo desensitization within 10–15 min, which may be related to nicotine addiction (Alkondon et al., 2000).

Nicotine at a dose equivalent to smoking 1 cigarette (0.1 mg/kg, s.c.), compared to saline, decreased k* for AA in 26 rat brain regions by 13% to 45% at 2 min but not 10 min after injection, consistent with the rapid in vitro desensitization of α4β2 nicotinic receptors (Chang et al., 2009). The 2 min signal could be blocked by mecamylamine, a nonselective and noncompetitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist. In summary, nicotine given to unanesthetized rats rapidly reduced AA signaling in brain regions containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, likely by modulating the presynaptic release of neurotransmitters acting on PLA2 coupled receptors The effect showed rapid desensitization and is produced at a nicotine dose equivalent to smoking one cigarette in humans. PET might be employed to see if acute nicotine or smoking has a similar transient effect on AA signaling in the human brain.

3. Pathways of AA metabolic loss from brain during rest and activation

Once released from brain phospholipids, unesterified AA can be oxidized to bioactive prostanoids (e.g., prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and thromboxane B2 (TXB2)) by COX enzymes (Phillis et al., 2006). Two COX enzymes are well described, COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 is constitutive while COX-2 is inducible and becomes overexpressed in activated cells at sites of inflammation. To test the COX-2 pathway of AA metabolic loss at rest and during activation, we studied unanesthetized mice in which COX-2 was deleted (COX-2−/−) and their wildtype (COX-2+/+) littermates (Morham et al., 1995), as well as unanesthetized rats acutely administered the non-specific COX inhibitor, flurbiprofen.

3.1 COX-2 knockout mice

In COX-2−/− compared with COX-2+/+ mice, baseline k* and Jin for AA were widely elevated (Basselin et al., 2006c). We interpreted these elevations as representing increased rates of AA metabolic loss by non-COX-2 mediated pathways, consistent with evidence in these mice of increased brain activities of cPLA2, sPLA2 and COX-1 (Bosetti et al., 2004). After administering the muscarinic M1,3,5 cholinergic agonist arecoline, we found robust responses in k* and Jin for AA in brain regions containing the receptors in the COX-2+/+ mice, whereas significant responses were entirely absent in the COX-2−/− mice. This demonstrated that the AA released by acute drug-induced receptor-mediated activation of muscarinic receptors coupled likely to cPLA2 (Bayon et al., 1997) was metabolized largely via the COX-2 pathway. This interpretation agrees with evidence that cPLA2 is functionally coupled to and co-localized with COX-2 at neuronal post-synaptic excitatory membranes (Ong et al., 1999; Pardue et al., 2003), and that genes for both enzymes are next to each other on human chromosome 1, thus likely co-evolved (Tay et al., 1995).

3.2 Acute effects of flurbiprofen in rats

Baseline values of k* and Jin for AA did not differ between unanesthetized rats given flurbiprofen, a non-specific COX inhibitor, compared with saline vehicle, 6 hours before tracer AA injection (Basselin et al., 2007b). Flurbiprofen also did not change baseline brain activities of cPLA2 or sPLA2, both AA-releasing enzymes. On the other hand, flurbiprofen blocked the arecoline-induced stimulation of k* and Jin for AA at brain sites of M1,3,5 receptors, which was widespread in vehicle-treated rats. Arecoline given to vehicle rats increased the brain concentration of PGE2, a preferred COX-2 product, but not of TXB2, a preferred COX-1 product. In flurbiprofen-treated rats it did not increase the concentration of either product.

Together, data from studies on the COX-2 knockout mouse and the flurbiprofen-treated rat showed that the AA signal following neuroreceptor activation by arecoline largely depends on COX-2.

4. Comparison with rCMRglc method

The rCMRglc method is based on evidence that brain functional activity, particularly at axon terminals, consumes energy in the form of ATP supplied by oxidative metabolism of glucose (Sokoloff, 1999). Imaging information using labeled AA is clearly distinct from information using labeled 2-deoxy-D-glucose to measure rCMRglc, and specific to PLA2 activation rather than to overall brain functional activity. Indeed, in vivo imaging following the intravenous injection of [14C]2-deoxy-D-glucose can be used to measure rCMRglc over an integrated period of 45 min, and thus would not be expected to pick up the transient reduction in metabolism identified with the pulse-labeling AA method. In this regard, in two studies from the same laboratory in unanesthetized rats (London et al., 1988a; London et al., 1988b), nicotine (0.1 mg/kg s.c., 2 min) reported increased rCMRglc following nicotine, whereas we showed decreased k* for AA following nicotine (Chang et al., 2009). A PET study of reported that intravenous 1.5 mg nicotine significantly reduced brain rCMRglc in 9 of 30 measured bilateral regions, (Stapleton et al., 2003). Similarly, rCMRglc data obtained in rodents and with PET in humans are contradictory when studying sleep homeostasis (Feinberg and Campbell, 2010), amphetamine (Porrino et al., 1984; Wolkin et al., 1987), and physostigmine (anticholinesterase) (Bassant et al., 1993; Blin et al., 1997).

In addition, large increases in k* for AA in brain regions containing appropriate receptors have been observed in rodents administered the muscarinic M1,3,5 receptor agonist arecoline (Basselin et al., 2003; Basselin et al., 2006c; Basselin et al., 2007b; DeGeorge et al., 1991; Nariai et al., 1991), the dopaminergic D2-like receptor agonist quinpirole (Basselin et al., 2005a; Bhattacharjee et al., 2005; Bhattacharjee et al., 2007; Bhattacharjee et al., 2008b; Hayakawa et al., 2001), the D1/D2 agonist apomorphine (Bhattacharjee et al., 2008b), the serotonergic 5-HT2A/2C agonist (+/−)2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl-2-amino propane (DOI) (Basselin et al., 2005a; Basselin et al., 2009a; Qu et al., 2005; Qu et al., 2006) or NMDA (Basselin et al., 2006a; Basselin et al., 2007a; Basselin et al., 2008a; Ramadan et al., 2011a). On the other hand, few reductions, increases, or no changes in rCMRglc were produced by the same agonists (Basselin et al., 2006b; Browne et al., 1998; Freo et al., 1991; Soncrant et al., 1985), demonstrating independence of the two measures. In agreement, AA incorporation into brain is entirely independent of changes in rCBF (Chang et al., 1997), which usually are coupled to rCMRglc (Sokoloff, 1999). Independence arises because AA signaling during neurotransmission consumes only a fraction of glucose consumption, which is largely depend on repolarization following depolarization.

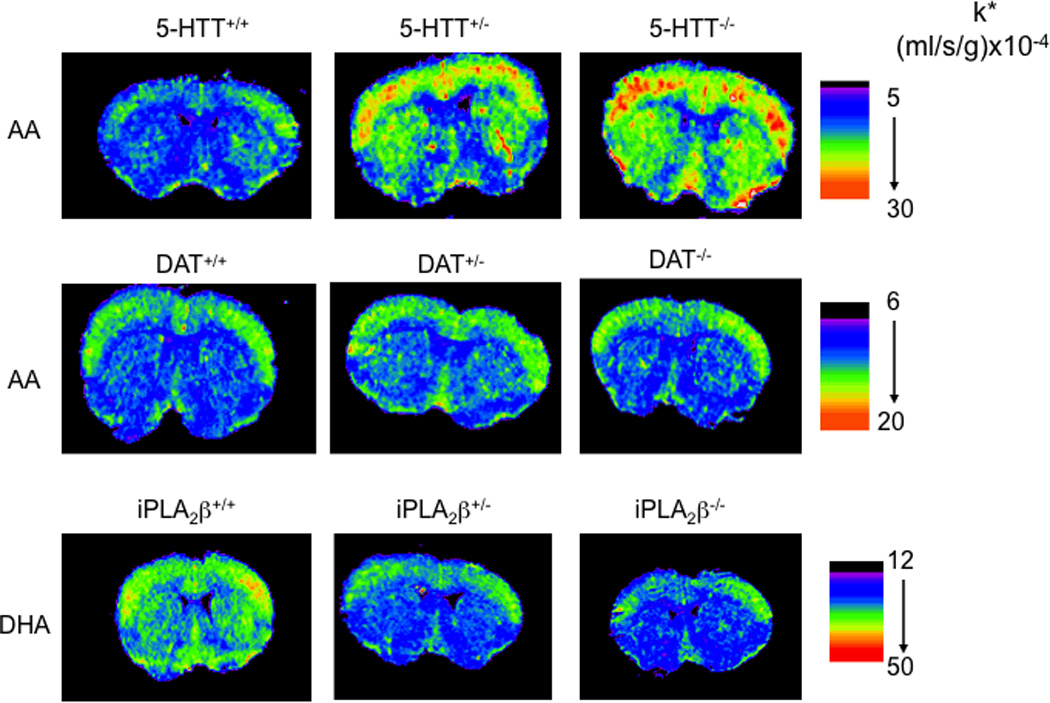

In COX-2−/− compared with COX-2+/+ mice, baseline values of k* for AA were elevated (see above) (Basselin et al., 2006c), whereas resting values of rCMRglc were not different (Niwa et al., 2000). In the homozygous serotonin reuptake transporter (5-HTT) deficient mouse (5-HTT−/−), baseline rCMRglc was lower in 17 brain regions compared to the wild-type 5-HTT+/+ mice (Esaki et al., 2005), whereas baseline k* was increased significantly in 45 and 72 of 92 brain regions analyzed in heterozygous 5-HTT+/− and 5-HTT−/− mice, respectively (Basselin et al., 2009a) (see below, Figure 6). In the dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT) knockout mouse (DAT−/−), baseline rCMRglc was significantly greater in the thalamus and cerebellum compared to the wildtype mouse (Thanos et al., 2008) whereas baseline k* for AA was unchanged (Ramadan E, Basselin M, Rapoport SI, unpublished data) (see below, Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Increased incorporation coefficients k* of arachidonic acid in 5-HTT-deficient but not in DAT-deficient mice, and decreased k* of docosahexaenoic acid in iPLA2β-deficient mice Coronal autoradiographs of brain showing effects of 5-HTT, DAT, and iPLA2β genotype on regional [1-14C]arachidonic acid or [1-14C]docosahexaenoic acid incorporation coefficients k* in mice. Values of k* are given on a color scale. From (Basselin et al., 2009a; Basselin et al., 2010b) and Ramadan et al. (unpublished data).

5. Cholinergic neurotransmission and desensitization to cholinergic drugs

Memory defects in Alzheimer’s disease have been ascribed in part to cholinergic dysfunction (Bartus et al., 1982). Donepezil, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, is used to treat the disease, although some clinical trials indicate no significant of drug on progression (Courtney et al., 2004; Howard et al., 2007). Donepezil is thought to act by increasing synaptic acetylcholine, thus indirectly stimulating postsynaptic muscarinic M1,3,5 receptors that may be coupled to cPLA2 (Bayon et al., 1997; DeGeorge et al., 1991).

Donepezil (3 mg/kg p.o.) compared with vehicle increased brain AA signaling in unanesthetized rats at 20 min, whereas k* for AA was unchanged 7 h after this dose or after 21 days of daily Donepezil (Basselin et al., 2009b). The response at 20 min could be blocked by pre-dosing with the muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine. At each measurement time, however, brain acetylcholine was elevated and acetylcholinesterase activity was reduced, and positive k* responses to arecoline could be produced. Desensitization of AA or related signals to Donepezil but not to arecoline could explain why acetylcholinesterase inhibitors may not slow Alzheimer’s disease progression (Courtney et al., 2004; Howard et al., 2007), and suggests that muscarinic agonists may prove more effective in treating the disease if the cholinergic hypothesis is valid (Jakubik et al., 2008).

6. Effects of chronic anti-bipolar disorder drugs

6.1 Theory of neurotransmission imbalance in bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder has been suggested to reflect a neurotransmission imbalance, consisting of excessive dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission, altered serotonergic, and reduced cholinergic muscarinic transmission (Berk et al., 2007; Hashimoto et al., 2007; Machado-Vieira et al., 2009; Rapoport et al., 2009). Cholinomimetics, dopamine or NMDA antagonists can be therapeutic, whereas drugs that stimulate brain dopamine synthesis or receptors, or reduce dopamine reuptake (amphetamine), can precipitate mania. Furthermore, some markers of the AA cascade have been reported to be abnormal in BD plasma, such as the AA concentration, PLA2 activity, plasma PGE2 level, and cytosolic PGE2 synthase (Chiu et al., 2003; Lieb et al., 1983; Maida et al., 2006; Sublette et al., 2007). Recently, our laboratory reported in postmortem BD compared with control brain upregulated mRNA and protein levels of AA cascade enzymes, including cPLA2-IVA, sPLA2-IIA, COX-2, and COX-1 (Kim et al., 2011b), decreased expression of G-protein subunits and of G-protein receptor kinase (GRK)-3 (Rao et al., 2009), reduced synaptic markers (Kim et al., 2010), and altered excitatory amino acid transporters (EAAT1 and EAAT2) and dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT) (Rao et al., 2012). These changes may account for disturbed behavior and cognition in BD (Rapoport et al., 2009).

Chronic administration of therapeutically relevant doses of each of three FDA-approved mood stabilizers for treating BD, lithium, carbamazepine (CBZ) and valproate (VPA) (Bowden and Karren, 2006; Post et al., 2007; Rapoport et al., 2009), reduced AA turnover in brain phospholipids of unanesthetized rats, without affecting DHA or palmitate turnover (Bazinet et al., 2006a; Bazinet et al., 2006b; Chang et al., 1996; Chang et al., 2001; Rapoport et al., 2009). In contrast, topiramate, which in phase III trials was found ineffective in BD (Kushner et al., 2006), had no effect on AA turnover in rat brain. Reduced turnover by lithium and CBZ was ascribed to an observed downregulation in brain of expression of Ca2+-dependent AA-selective cPLA2 A without a change in sPLA2-IIA or iPLA2-VIA expression, while VPA was shown to noncompetitively inhibit AA acylation by rat acyl-CoA synthetase 4 (Bazinet et al., 2006b; Bosetti et al., 2002; Bosetti et al., 2003; Chang and Jones, 1998; Ghelardoni et al., 2004; Rintala et al., 1999; Shimshoni et al., 2011; Weerasinghe et al., 2004). Each of the agents reduced brain COX-2 expression, whereas VPA also reduced COX-1 expression. Each agent also reduced brain PGE2 concentration, and VPA like CBZ decreased the brain TXB2 concentration (Basselin et al., 2007a; Basselin et al., 2008a; Basselin et al., 2008b; Bosetti et al., 2002; Bosetti et al., 2003; Ghelardoni et al., 2004; Ramadan et al., 2011b). Lithium and CBZ each reduced expression and DNA binding of activator protein 2 (AP-2), a cPLA2 transcription factor (Rao et al., 2005; Rao et al., 2007). COX-2 mRNA downregulation by VPA correlated with decreased DNA binding activity of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B (NF-κB) (Rao et al., 2007).

Lamotrigine (LTG), another FDA-approved mood stabilizer (Amann et al., In Press), is preferred for bipolar depression (Calabrese et al., 2002). LTG did not affect brain cPLA2-IVA activity or AA turnover when given chronically to rats, but reduced brain COX activity, COX-2 protein and mRNA, NF-κB DNA binding activity, and PGE2 concentration (Lee et al., 2007a; Lee et al., 2008; Ramadan et al., 2011a).

To see if lithium, VPA, CBZ, and LTG could correct the neurotransmission imbalance thought to operate in BD (see above), and to see if these imbalances might involve signaling via AA, we used our fatty acid method in unanesthetized rats to examine chronic effects of the drugs on k* and Jin for AA in response to different pharmacological challenges directed at receptors coupled to PLA2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mood stabilizers modulate neuroreceptor signaling via arachidonic acid in unanesthetized rats

| Lithium | Carbamazepine | Valproate | Lamotrigine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMDA (NMDA) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| D2-like (Quinpirole) | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ND |

| M1,3,5 (Arecoline) | ↑ | ND | ND | ND |

| 5-HT2A/2C (DOI) | ↓in auditory and visual areas | ND | ND | ND |

Each mood stabilizer was administered chronically to produce a plasma concentration therapeutically relevant to bipolar disorder, and compared with chronic vehicle. Effect on responses to agonists shown were measured and compared to response in saline injected animals. ND, not determined; DOI, (+/−)-1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane hydrochloride. From (Basselin et al., 2003; Basselin et al., 2005a; Basselin et al., 2005b; Basselin et al., 2006a; Basselin et al., 2007a; Basselin et al., 2008a; Basselin et al., 2008b; Ramadan et al., 2011a; Ramadan et al., 2011b)

6.2 Muscarinic cholinergic M1,3,5 receptors

In rats fed LiCl for 6 weeks to produce a therapeutically relevant brain Li+ concentration (Bosetti et al., 2002), baseline values of k* for AA in brain auditory and visual areas were significantly greater than in rats fed a Li+-free control diet. Arecoline (2 and 5 mg/kg i.p.) increased k* in widespread brain areas in rats fed the control diet as well as the LiCl diet. However, arecoline-induced increments often were significantly greater in the LiCl-fed than control rats in auditory and visual regions (Figure 4) (Basselin et al., 2003), which may be consistent with lithium’s ability to increase auditory and visual evoked responses in humans. Lithium’s augmentation of k* responses to arecoline may underlie its "proconvulsant" action with cholinergic drugs, as AA and its eicosanoid metabolites can increase neuronal excitability and seizure propagation (Jope, 1993; Ormandy et al., 1991). Similarly, in unanesthetized rats, chronic lithium widely upregulated baseline rCMRglc, and potentiated the negative effects on rCMRglc of D2-like receptor stimulation (Basselin et al., 2006b).

Figure 4.

Mood stabilizers downregulate NMDA and D2-like induced arachidonic acid signal. Coronal autoradiographs of brain showing effects of the four mood stabilizers on NMDA and D2-like signal on regional [1-14C]arachidonic acid incorporation coefficients k* in rats. NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; ND, not determined. From (Basselin et al., 2005a; Basselin et al., 2006a; Basselin et al., 2007a; Basselin et al., 2008a; Basselin et al., 2008b; Ramadan et al., 2011a; Ramadan et al., 2011b).

6.3 Serotonergic 5-HT2A/2C receptors

Lithium feeding to rats has been reported to augment brain 5-HT release, 5-HT2A/2C agonist-induced locomotor activity, phosphoinositide-linked 5-HT-receptor stimulation, and agonist-induced Fos-like immunoreactivity throughout the cerebral cortex (Jacobsen and Mørk, 2004; Moorman and Leslie, 1998; Williams and Jope, 1994). In this regard, in rats fed LiCl for 6 weeks, the 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist, DOI (1 mg/kg, i.p.), significantly increased k* in widespread brain areas containing 5-HT2A/2C receptors. Responses did not differ from those in control diet rats in most brain regions, except in auditory and visual areas, where the response was blocked (Basselin et al., 2005b).

6.4 Dopaminergic D2-like receptors

In rats fed a control diet and treated with vehicle, the D2-like dopamine receptor agonist quinpirole (1 mg/kg, i.v.) increased k* for AA significantly in regions belonging to dopaminergic circuits and with high densities of D2-like receptors, as well as the brain PGE2 concentration (Basselin et al., 2005a; Basselin et al., 2008b; Ramadan et al., 2011b) (Figure 4). Quinpirole-induced activation could be blocked by the D2-like receptor antagonists butaclamol or raclopride (Bhattacharjee et al., 2008b; Hayakawa et al., 2001), by pretreatment with LiCl (1.70 g LiCl/kg for 4 weeks, followed by chow containing 2.55 g LiCl/kg for 2 weeks), with CBZ (25 mg/kg/day, i.p. for 30 days), or with VPA (200 mg/kg/day, 30 days) (Basselin et al., 2005a; Basselin et al., 2008b; Ramadan et al., 2011b) (Figure 4).

Lithium, CBZ and VPA could have reduced D2-like receptor-initiated AA signaling in any of several ways. A direct interference with dopamine release and receptor function could have resulted from modification of dopamine release, the dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT), brain D2 receptor density, D2-like coupled Gαo/i, D2-like receptor phosphorylation, or histone deacetylation (Basselin, 2005 #3027;Basselin, 2008 #3029; Ramadan, In Press #5589;Marinova, 2009 #4352;Wang, 2007 #5392;D'Souza, 2009 #3395}. In addition, chronic lithium increases levels of dopamine and cyclic AMP-regulated phosphoprotein (DARPP-32) in rat frontal cortex, which regulates dopaminergic neurotransmission and is decreased in BD brain (Guitart and Nestler, 1992; Ishikawa et al., 2007). Lithium and CBZ’s ability to downregulate brain cPLA2 transcription and activity and as well as COX activity (with VPA) also could have contributed to the reduced baseline PGE2 and/or TXB2 concentrations, and to inhibition of the quinpirole effects on these concentrations (for CBZ) and the k* signal (Bosetti et al., 2002; Bosetti et al., 2003; Chang and Jones, 1998; Ghelardoni et al., 2004; Rintala et al., 1999).

6.5 Glutamatergic NMDA receptors

In control diet rats and in chronic vehicle-treated rats, NMDA (25 and 50 mg/kg i.p.) compared with saline increased k* for AA in brain regions rich in NMDARs, as well as brain concentrations of PGE2 and TXB2 (Basselin et al., 2006a; Basselin et al., 2007a; Basselin et al., 2008a; Ramadan et al., 2010) (Figure 4). The increases could be blocked by a 6-week LiCl diet, 30-day VPA (200 mg/kg/day, i.p.) or 30-day CBZ (25 mg/kg/day, i.p.) pretreatment (Basselin et al., 2006a; Basselin et al., 2007a; Basselin et al., 2008a) (Figure 4).

Chronic LTG administration for 42 days (10 mg/kg/day, p.o.) compared with vehicle reduced rat brain COX activity, PGE2 and TXB2 concentrations, and DNA binding activity of the COX-2 transcription factor, NF-κB. Chronic LTG also blocked increments in k* and Jin for AA following NMDA (Figure 4) (Ramadan et al., 2011a).

To the extent that BD symptoms reflect increased brain glutamatergic transmission and upregulated AA metabolism, the therapeutic efficacy of the four FDA-approved mood stabilizers may depend on blocking upregulated NMDA signaling involving AA. Indeed, BD has been associated with increased or otherwise disturbed brain glutamatergic neurotransmission (Beneyto et al., 2007; Martucci et al., 2006; McCullumsmith et al., 2007; Ongür et al., 2008), and lithium, VPA, and LTG decreased glutamine + glutamate or glutamate/glutamine ratio in healthy volunteers (Shibuya-Tayoshi et al., 2008) and in BD brains (Dager et al., 2004; Frye et al., 2007; Lan et al., 2009). Furthermore, the non-competitive NMDA antagonist memantine has shown some efficacy in treating bipolar mania (Keck et al., 2009).

When administered chronically at therapeutically relevant doses, the four mood stabilizers attenuated brain NMDA receptor-initiated signaling via AA. Because chronic VPA and LTG had no effect on cPLA2-IV activity, protein or mRNA level, while chronic LiCl and CBZ downregulated these levels (Bosetti et al., 2003; Chang and Jones, 1998; Ghelardoni et al., 2004; Rao et al., 2007; Rao et al., 2007; Rintala et al., 1999), these data suggest that this NMDA signal attenuation was due to decreased glutamate release and/or defective NMDARs, and that reduction of AA cascade follows chronic downregulation of extracellular Ca2+ entry. Indeed, chronic LiCl, CBZ and VPA were reported to inhibit cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) and/or PKC, either of which can phosphorylate NMDARs (Basselin et al., 2006b; Basselin et al., 2007a; Basselin et al., 2008b), thereby reducing NMDAR function. Because activation of NMDARs increased in vitro acetylation of histone H3 and H2A.X via PKC/ERK signaling cascade, CBZ and VPA, inhibitors of histone deacetylases (Beutler et al., 2005; Gurvich et al., 2005), also may affect histones as well as transcription factors that are regulated by acetylation such as specificity protein-1 (Sp1), a NMDAR transcription factor (Basselin et al., 2006a; Basselin et al., 2007a; Basselin et al., 2008a). In addition, chronic VPA downregulated expression of two NMDAR-interacting proteins in rat brain, the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 and type II Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase beta subunit (Bosetti et al., 2005). For LiCl, in vitro studies showed that the drug reduces NMDAR-mediated Ca2+ influx by inhibiting NR2B tyrosine phosphorylation and Src tyrosine kinase (Hashimoto et al., 2003), or by reducing NR2A tyrosine phosphorylation and interactions of the NR2A subunit with Src and Fyn mediated by PSD-95 in rat hippocampus (Ma et al., 2004). Chronic VPA and LTG also decreased glutamate release and the glutamate/glutamine ratio in rat brain (Ahmad et al., 2004; Lan et al., 2009) and VPA and lithium upregulated glutamate uptake, which decreased glutamate in the synaptic cleft (Dixon and Hokin, 1998; Hassel et al., 2001; Thurston and Hauhart, 1989; Ueda and Willmore, 2000). If blocking NMDAR-mediated Ca2+ entry into neurons or reducing glutamate release were the primary reasons for the reduced k* responses, then the reduction of global AA cascade (COX and cPLA2) by mood stabilizers may be secondary to a chronic downregulation of Ca2+ entry via NMDARs.

We have shown that the four mood stabilizers blocked NMDAR-initiated, and that chronic lithium, CBZ and VPA blocked D2-like receptor-initiated signaling via AA in rat brain (Table 1), which is consistent with evidence of disturbed NMDA and dopamine neurotransmission in the BD brain (see above). The common effects may be related to the fact that dopaminergic and glutamatergic/NMDA transmission are closely linked in the mammalian brain and interact with each other (Tarazi and Baldessarini, 1999; Tseng and O'Donnell, 2004; Wang et al., 2003). Furthermore, the dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein (DARPP-32), which is a key actor of dopamine and glutamate signals (Fernandez et al., 2006), is altered in BD patients (Ishikawa et al., 2007).

7. Animal models of neuroinflammation and effects of lithium

Neuroinflammation has emerged as a key player in many human psychiatric, degenerative and other brain diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, HIV-1 associated dementia, and BD (Anthony and Bell, 2008; McGeer et al., 2006; Rao et al., 2010; Tansey et al., 2007; Terao et al., 2006; Zhong and Lee, 2007). For example, we reported that postmortem frontal cortex from BD patients shows increased levels of neuroinflammatory markers such as IL-1β and its receptor, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and microglia/macrophages CD11b, as well as upregulated AA cascade enzymes and decreased synaptic markers drebrin and synaptophysin (Kim et al., 2011b; Rao et al., 2010). Increased synthesis and release of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-1β, prostaglandins, reactive oxygen species, and nitric oxide by microglia can activate astrocytes and neurons to release glutamate and secondarily activate cPLA2 via post-synaptic NMDARs (Bal-Price et al., 2002; Malarkey and Parpura, 2008; Perea and Araque, 2007; Tilleux and Hermans, 2007), or directly activate cPLA2 and sPLA2 via cytokine receptors (Dinarello, 2002; Luschen et al., 2000). Thus, an in vivo method to image a disturbed AA cascade in neuroinflammation could help to evaluate how and where neuroinflammation contributes to disease progression, and to design appropriate therapy.

7.1 LPS infusion

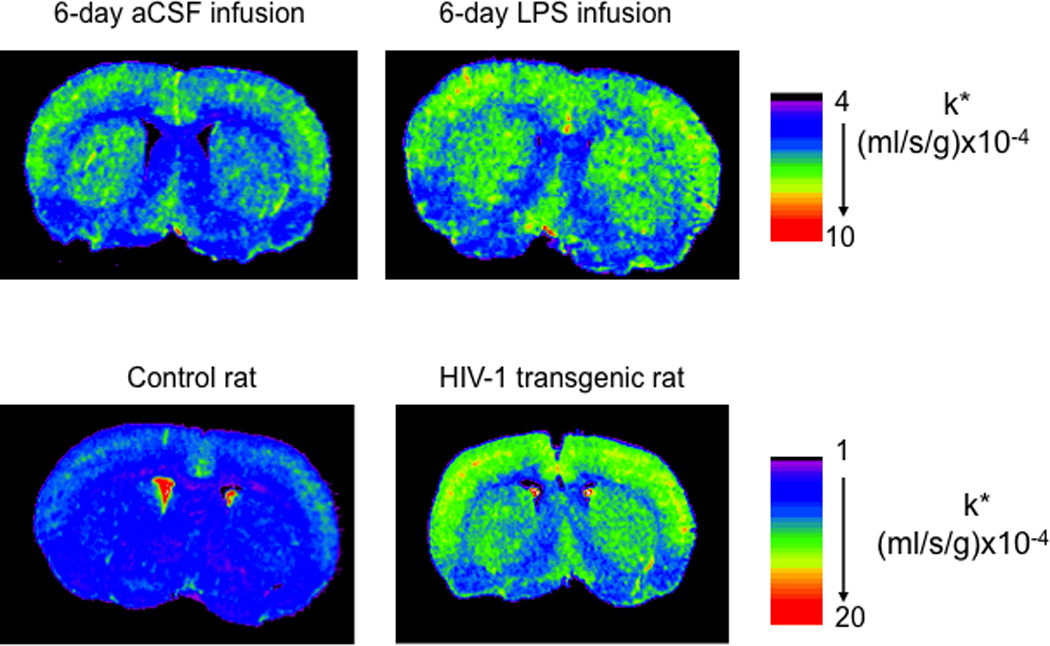

In a rat model of neuroinflammation, six days of intracerebroventricular infusion of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), at a rate of 0.5 ng/h, increased whole brain activities of cPLA2-IV and sPLA2, turnover rates of AA in brain phospholipids, and brain concentrations of unesterified AA and of its PGE2, TXB2 and leukotriene B4 metabolites, without altering DHA metabolism (Basselin et al., 2007c; Basselin et al., 2010a; Basselin et al., 2011a; Rosenberger et al., 2004; Rosenberger et al., 2010). Longer infusion of LPS caused behavioral changes and microglial activation, which could be reduced by ibuprofen (Richardson et al., 2005). The evidence of upregulated brain AA metabolism was confirmed by elevated k* for AA into brain phospholipids, measured following the intravenous injection of [1-14C]AA by quantitative autoradiography (Figure 5) and brain analysis (Basselin et al., 2007c; Lee et al., 2004; Rosenberger et al., 2004).

Figure 5.

Increased incorporation coefficients k* of arachidonic acid after 6-day LPS infusion and in HIV-1 transgenic rat. Coronal autoradiographs of brain after 6-day LPS infusion (0.5 ng/h) and in HIV-1 transgenic rats on regional [1-14C]arachidonic acid incorporation coefficients k* in rats. Values of k* are given on a color scale. aCSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide. From (Basselin et al., 2007c; Basselin et al., 2011b).

Feeding LiCl to rats for 6 weeks, to produce plasma and brain lithium concentrations therapeutically relevant to BD, prevented many of the LPS-induced changes (Basselin et al., 2007c; Basselin et al., 2010a). In rats on a control LiCl-free diet, LPS compared with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) infusion increased k* significantly in 28 regions, as well as brain cPLA2-IV activity and PGE2 and TXB2 concentrations; the LiCl diet prevented these increments (Figure 5). The animal data are consistent with a study showing that lithium treatment restored the imbalance in production of IL-1β and IL-6 by monocytes from BD patients (Knijff et al., 2007). In addition, chronic lithium treatment of the rats increased brain levels of a 17-hydroxy-DHA (Basselin et al., 2010a), a DHA metabolite that is a precursor of anti-inflammatory compounds known as docosanoids (Hong et al., 2003; Serhan, 2006). Aspirin is known to also enhance 17(R)-OH-DHA formation by acetylating COX-2 (Meade et al., 1993; Serhan et al., 2004). By reducing both pro-inflammatory AA products and increasing anti-inflammatory DHA products, lithium exerts a dual protective effect, which may explain why it may help in treating neuroinflammation in BD and schizophrenia (Laan et al., 2010; Stolk et al., 2010). Lithium thus might be considered for treating other human brain diseases accompanied by neuroinflammation, which has been recently suggested for Alzheimer’s disease (Nunes et al., 2007; Terao et al., 2006; Zhong and Lee, 2007), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (Forlenza et al., 2011), and HIV-1 associated dementia (Letendre et al., 2006). VPA and CBZ effects on an upregulated AA cascade caused by LPS infusion could also be tested, since both drugs are reported to have anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects (Chen et al., 2007; Matoth et al., 2000).

With regard to aspirin, we recently showed that 6-week aspirin (low and high doses) reduced rat brain pro-inflammatory PGE2 and TXB2, and increased anti-inflammatory lipoxin A4 and 15-epi-lipoxin A4 induced by 6-day low-dose LPS (0.5 ng/h) infusion (Basselin et al., 2011a). Aspirin, when given chronically, reduced untoward effects in (presumably) BD patients on lithium therapy (Stolk et al., 2010), and reduced symptoms in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder, in whom neuroinflammation may play a role (Doorduin et al., 2009; Laan et al., 2010).

7.2 HIV-1 transgenic rat

HIV-1 associated dementia (HAD) is accompanied by microglial activation and neuroinflammation (Anthony and Bell, 2008; Avison et al., 2004). Despite the widespread use of highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART), cognitive impairment, neuroinflammation, and neuronal injury persist (Harezlak et al., 2011). Thus, it would be of interest to be able to image these or related processes in the course of HIV-1 and its treatment. In a noninfectious transgenic rat model for HIV-1 dementia (Reid et al., 2001), we found evidence of increased neuroinflammation associated with an upregulated brain AA cascade and dendritic spine loss (Basselin et al., 2011b; Rao et al., 2011).

By using our fatty acid method with quantitative autography, we showed that values of k* and of the incorporation rate Jin of plasma unesterified AA into phospholipids were elevated significantly in 69 of the 81 brain regions examined in 7–9-month-old male HIV-1 Tg rats compared with control rats (Figure 5). Brain cPLA2-IV, sPLA2 and iPLA2-VI mRNA, protein and activity levels, and PGE2 and leukotriene B4 concentrations, also were increased in HIV-1 Tg compared to control rats (Basselin et al., 2011b; Rao et al., 2011). The results indicate that our in vivo imaging method can detect an increase in AA signaling in HIV-1 Tg rats, and suggest the using PET with [1-11C]AA to image an upregulated AA signal as a marker of neuroinflammation in HIV-1 patients.

8. AA and DHA signaling in rodent models with clinical relevance

8.1 Serotonin reuptake transporter (5-HTT)-deficient mice

Serotonergic (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) neurotransmission is disturbed in a number of neuropsychiatric conditions (Coccaro, 1989; Mahmood and Silverstone, 2001; Owens and Nemeroff, 1994). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine (Prozac), have been used to treat some of these disturbances, and are thought to do so by increasing synaptic 5-HT. In this regard, subjects with the short (S) compared to long (L) allele of the presynaptic serotonin reuptake transporter (5-HTT) promoter, have increased extracellular 5-HT and are more at risk for neuropsychiatric disease (Malloy-Diniz et al., 2011). The heterozygous, 5-HTT (5-HTT+/−) mouse, which has elevated brain synaptic 5-HT and shows depressive-like behavior, is considered a model for humans carrying the “S” promoter allele (Murphy et al., 2003).

We reported increased baseline values k* for AA by 20–70% in brains of 5-HTT+/− and 5-HTT−/− compared to 5-HTT+/+ mice, and elevated cPLA2 activity suggesting tonic stimulation of cPLA2-coupled 5-HT2A/2C receptors (Basselin et al., 2009a). These data are consistent with data in rats given chronic fluoxetine. Thus, 21 days of daily fluoxetine followed by 3 days of washout upregulated the AA signal at 5-HT2A/2C receptor sites, and increased brain cPLA2-IV activity (Lee et al., 2007b; Qu et al., 2006). It remains to determine if transiently inhibited 5-HTT function during early development would produce an abnormal brain AA metabolism in adulthood, as long term deleterious effects of maternal and childhood SSRI administration have been reported (Olivier et al., 2011). In this regard, transient inhibition by fluoxetine of 5-HTT function during postnatal development of mice produced depression- and anxiety-related behaviors in adulthood that mimicked the behavioral phenotype of mice lacking the 5-HTT gene (Ansorge et al., 2004; Karpova et al., 2009). Measuring brain [1-11C]AA incorporation with PET could be used to evaluate the effects of the short and long HTT promoter alleles in psychiatric disorders.

8.2 Dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT)-deficient mice

Dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT) gene variants affecting DAT expression are associated with BD, and changes in the DAT play a role in psychostimulant addiction and other human brain disorders (Pinsonneault et al., 2011; Zahniser and Sorkin, 2009). Recently, our laboratory reported in postmortem BD compared with control frontal cortex downregulated mRNA and protein levels of DAT (Rao et al., 2012). To understand its role in AA signaling, we studied mice in which the transporter was knocked out (DAT−/−) on brain AA metabolism (Bhattacharjee et al., 2005; Nilsson et al., 1998). These mice have a 10-fold higher extracellular dopamine concentration in the caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens than do heterozygous DAT+/− or wildtype DAT+/+ mice (Shen et al., 2004). The lifetime deletion of the DAT gene did not significantly affect baseline values of k* or Jin, markers of AA consumption and signaling, in any of 83 brain regions examined, compared with values in wildtype mice, nor brain cPLA2 activity (Ramadan et al., unpublished data). Multiple alterations in DA neurotransmission at presynaptic and postsynaptic levels likely maintain this aspect of dopaminergic signaling despite the increased extracellular dopamine produced by DAT deletion (Gainetdinov et al., 1999; Sora et al., 1998). In contrast, chronic amphetamine (which increases synaptic dopamine by retrograde transport via the DAT, after blocking vesicular transport) followed by a 1-day washout decreased baseline AA incorporation into brain regions belonging to dopaminergic circuitry in unanesthetized rats (Bhattacharjee et al., 2008a).

The results involving DAT deficiency contrast with upregulated k* and Jin for AA and increased cPLA2 activity in 5-HTT deficient mice with elevated brain 5-HT levels, and show that our in vivo AA imaging method can distinguish differences in neuroplastic responses to chronic changes in brain neurotransmitter levels. Similar differences might be examined in humans having abnormal brain DAT or 5-HTT expression, when using our fatty acid model with PET (Esposito et al., 2008; Giovacchini et al., 2004).

8.3 Rat model of unilateral Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson's disease involves loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, causing fewer presynaptic DATs but more postsynaptic dopaminergic D2 receptors in terminal areas of these neurons (Hornykiewicz, 1982; Ichise et al., 1999; Ribeiro et al., 2002). Using our in vivo method, D-amphetamine (5.0 mg/kg i.p.), quinpirole (1.0 mg/kg i.v.), or saline was administered to unanesthetized rats having a chronic unilateral lesion caused by injecting the selective monoaminergic toxin, 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), into one substantia nigra. In rats given saline, baseline k* was elevated in many regions on the lesioned compared with intact hemisphere (Bhattacharjee et al., 2007; Hayakawa et al., 1998; Hayakawa et al., 2001). Quinpirole increased k* in frontal cortical and basal ganglia regions bilaterally, more so on the lesioned than intact hemisphere (its effects could be prevented by the dopamine receptor antagonist butaclamol). D-amphetamine increased k* bilaterally but less so on the lesioned hemisphere (Bhattacharjee et al., 2007). The increased baseline elevations of k* and increased responsiveness to quinpirole in the lesioned hemisphere are consistent with their higher D2-receptor (Ichise et al., 1999), COX-2 protein and cPLA2 activity and protein levels (Lee et al., 2010), whereas the reduced responsiveness to D-amphetamine is consistent with dropout of presynaptic elements containing the DAT (Ribeiro et al., 2002). Thus, in vivo imaging of AA signaling using dopaminergic drugs can identify pre- and postsynaptic dopaminergic changes in animal models of Parkinson’s disease or other dopaminergic dysfunctions, and possibly in humans with PET (see below) (Thambisetty et al., In Press).

8.4 iPLA2β (VIA)-deficient mice

Mutations in the PLA2G6 gene encoding iPLA2β have been associated with infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy, idiopathic neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (Gregory et al., 2008; Morgan et al., 2006), and adult-onset dystonia-parkinsonism without brain iron accumulation (Hayflick, 2009; Paisan-Ruiz et al., 2009; Schneider et al., 2009). To investigate the contribution of iPLA2β to DHA signaling, we imaged k* and Jin for DHA in brains of unanesthetized iPLA2β−/−, iPLA2β+/− and iPLA2β+/+ mice, at baseline and following administration of the cholinergic muscarinic M1,3,5 receptor agonist, arecoline. Prior study showed that administration of the arecoline increased [1-14C]DHA incorporation into synaptic membrane phospholipid in rat brain (DeGeorge et al., 1991; Jones et al., 1997). Consistent with iPLA2β's reported ability to selectively hydrolyze DHA from phospholipid in vitro (Garcia and Kim, 1997; Strokin et al., 2003), a congenital partial or complete absence of iPLA2β in 4-month-old mice (which unlike 9-month-old mice do not show significant neuropathology) reduced brain DHA signaling and metabolism at baseline and following arecoline (Figure 6) (Basselin et al., 2010b). Our observations suggest that brain DHA signaling and metabolism would be altered in patients with a PLA2G6 mutation (Gregory et al., 2008; Hayflick, 2009; Morgan et al., 2006; Paisan-Ruiz et al., 2009). This could be tested directly by quantitatively imaging regional brain DHA incorporation in these patients, using PET (Rapoport et al., 2011; Umhau et al., 2009).

9. PET imaging of human brain AA or DHA metabolism

Our in vivo animal studies provide scientific rationales and experimental procedures for using PET with radiolabeled [1-11C]AA or [1-11C]DHA to image brain lipid metabolism at rest and during activation in health and disease in human subjects. After we reported a PET procedure in monkeys for their use, and showed that tracer uptake was independent of rCBF (Chang et al., 1997), we applied PET for clinical studies.

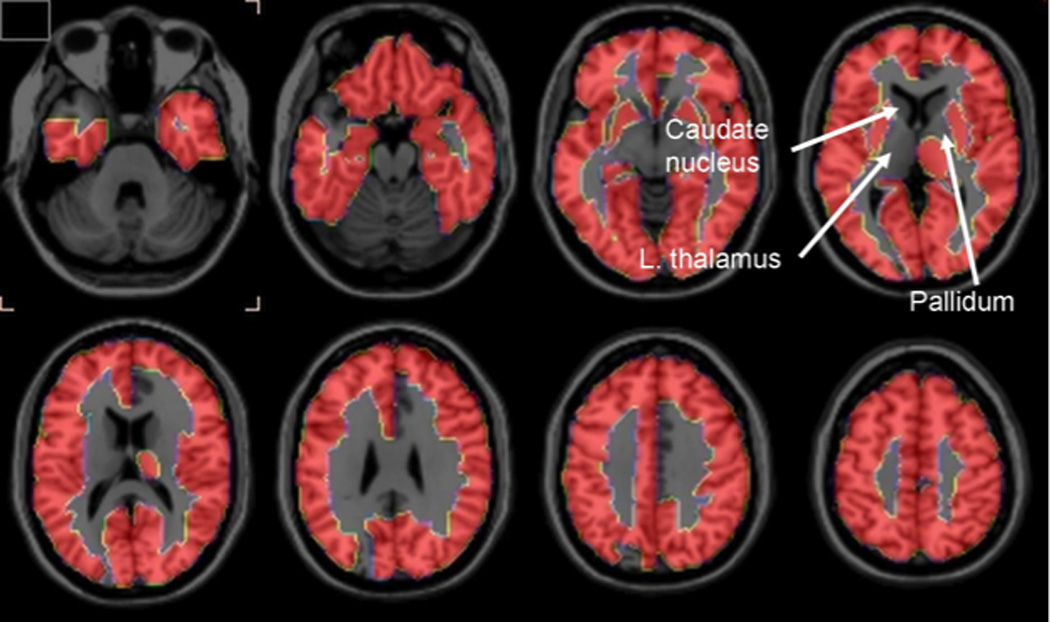

9.1 Imaging brain AA incorporation in healthy volunteers

9.1.1 At rest

Healthy young adults were scanned following serial i.v injections of [15O]H2O to measure rCBF and of [1-11C]AA to measure k* for AA, when taking into account the 2 min and 20 min radioactive half-lives of [15O] and [11C]. Using an equation that includes the radioactive arterial input function, brain uptake of [11C]CO2 and brain blood volume, we quantified resting state values of k* for AA in gray and white matter regions and showed them to have a 3/1 ratio (Giovacchini et al., 2002). In a second publication, after partial volume correction (PVC) for brain atrophy, we showed that neither rCBF nor k* or Jin for AA (Eq. A3) differed significantly between old and young healthy volunteers (Giovacchini et al., 2004). These findings agreed with our demonstrating an age-invariance of PVC-corrected rCMRglc in healthy men (Ibanez et al., 2004).

9.1.2 After visual activation

We used our published visual test-retest paradigm (Mentis et al., 1998), and the fact that we reported regional increments in k* for AA following visual activation (Wakabayashi et al., 1995) to image rCBF and brain AA incorporation in healthy subjects exposed to visual flash stimulation at 2.9 or 7.8 Hz and a dark (0 Hz) condition in the same PET session. We injected [15O]H2O and [1-11C]AA in each of the two conditions, and developed equations to take into account radioactive half-lives. The stimulation vs. the dark condition increased rCBF by 3.1–22% and k* for AA by 2.3–8.9% and in comparable brain visual and areas (Esposito et al., 2007), a 2/1 activation ratio that we had also found in rats. Thus, sensory stimulation can increase k* at sites of increased neuronal activity measured by rCBF, and likely reflects signaling related to glutamatergic neurotransmission.

9.1.3 After dopaminergic activation

To date, no PET method is available to image postsynaptic dopaminergic signal transduction “beyond the receptor”(Verhoeff, 1999). Since AA signaling can be coupled to D2-like receptor initiated AA hydrolysis from phospholipids by cPLA2 (Nilsson et al., 1998; Vial and Piomelli, 1995) (see 2.1 Receptors coupled to PLA2 by G-proteins) and the D1/D2 agonist apomorphine stimulated rat brain AA signaling via D2-like receptors (the signal could be blocked by the selective D2 antagonist raclopride) (Bhattacharjee et al., 2008b), we measured rCBF followed by AA signaling using PET in 12 healthy volunteers given vehicle followed by apomorphine (Thambisetty et al., In Press). We observed widespread increases as well as decreases in k*, and increments in rCBF in response to apomorphine. The changes in AA incorporation likely reflect neuronal signaling events downstream of activated D2-like receptors coupled to cPLA2 within the striatum. The observed changes in rCBF are broadly consistent with previous studies and demonstrate net functional effects of D1/D2 receptor activation. The [1-11C]AA PET method thus may be useful for studying disturbances of dopaminergic neurotransmission in conditions such as BD, schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease. Indeed, hyperdopaminergic signaling and an upregulated brain AA cascade are suggested to be involved in the pathophysiology of these diseases (Berk et al., 2007; Bhattacharjee et al., 2007; Cousins et al., 2009; Hayakawa et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2011b; Lee et al., 2010; Mattammal et al., 1995; Rao et al., 2012; Ross et al., 2001).

9.2 Increased brain AA incorporation in Alzheimer’s disease as surrogate marker of neuroinflammation

Neuroinflammation occurs in Alzheimer’s disease (McGeer and McGeer, 2010), and the postmortem Alzheimer brain demonstrates elevated expression of cPLA2, sPLA2, COX-2, and NF-κB, associated with increased IL-1β, TNFα, GFAP protein, CD11b, activated microglia surrounding senile (neuritic) plaques, and decreased synaptophysin and drebrin, pre- and postsynaptic markers (Colangelo et al., 2002; Hoozemans et al., 2001; Kitamura et al., 1999; Rao et al., In press; Stephenson et al., 1996). A CBF independent in vivo method to image biomarkers of neuroinflammation in humans, for diagnosis and evaluating disease progression and drug efficacy, would be very useful, but is unavailable to date (Chauveau et al., 2008). In 8 mildly-moderately demented Alzheimer patients, compared with 9 controls, k* for AA was significantly elevated in the neocortex (particularly in regions reported to have high densities of senile (neuritic) plaques with activated microglia) but not in basal ganglia or thalamic regions (Esposito et al., 2008), whereas rCBF, measured using [15O]H2O, was reduced. The pattern of Alzheimer’s disease-related differences in k* for AA in this study might be compared to differences found with other relevant PET compounds. For example, brain uptake of [11C](R)-PK11195, a ligand for peripheral benzodiazepine receptors on activated brain microglia, was increased in cortical but not subcortical regions in Alzheimer’s disease compared with control subjects (Cagnin et al., 2001; Versijpt et al., 2003), as was uptake of [11C]PIB (Pittsburgh compound B), a ligand for fibrillar Aβ-amyloid plaques (Kemppainen et al., 2006). Comparisons with [11C]PIB imaging may be particularly important in the course of Alzheimer’s disease, as β-amyloid peptide alone can stimulate cytokine formation and activate PLA2 before senile plaques accumulate (Lehtonen et al., 1996; Mattson and Chan, 2003). However, studies have identified PIB-positive cases in otherwise healthy older individuals (10–30%), limiting diagnostic specificity (Quigley et al., 2010), and the PIB ligand is not an in vivo marker of neurodegeneration, which is related to clinical and cognitive symptoms (Furst et al., 2010; Jack et al., 2009). On the other hand, [11C]PK11195 displays a high level of nonspecific binding and a poor signal-to-noise ratio which complicates its quantification (Chauveau et al., 2008).

Based on measured increased incorporation of plasma AA into rodent brain in two models of neuroinflammation, LPS infused and HIV-1 Tg rats, associated with neuroinflammation and with reduced synaptic markers drebrin and synaptophysin (Basselin et al., 2007c; Lee et al., 2004; Rao et al., 2011; Rosenberger et al., 2004), PET with [1-11C]AA may help to image neuroinflammation in relation to progression and dementia severity in Alzheimer’s disease.

9.3 Imaging brain DHA metabolism in healthy volunteers

Values of k* for DHA were higher in gray than white matter regions and correlated significantly with values of rCBF in 12 of 14 subjects despite evidence that rCBF does not directly influence k* (Umhau et al., 2009). For the entire human brain, the net DHA incorporation rate Jin (equivalent to consumption rate) equaled 3.8 ± 1.7 mg/day, compared with 17.8 mg/day for AA (Giovacchini et al., 2002; Giovacchini et al., 2004). Using PET, DHA metabolism might be examined in humans having DHA deficiency such as Zellweger's syndrome (Martinez, 1992), depression (McNamara et al., 2007a), schizophrenia (McNamara et al., 2007b) or in patients with a PLA2G6 mutation (see iPLA2β (VIA)-deficient mice).

10. Conclusions

A major limitation of in vivo neuroimaging to date has been the inability to localize and quantify post-synaptic or post-receptor signal transduction, which may involve a number of processes and second messengers, with complex downstream effects on cognition, behavior and on pathological processes including neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity. Briefly, by injecting the radiolabeled AA or DHA intravenously, and localizing its uptake in brain using quantitative autoradiography in animals or PET in humans, then normalizing to integrated plasma activity (input function), we can determine where and to what extent changes in signaling occur involving these polyunsaturated fatty acids. We can interpret the results quantitatively, since k* and Jin stoichiometrically represent the AA or DHA that has been lost at baseline or in response to drug due to release from phospholipid by a PLA2. These terms are independent of changes in rCBF, thus reflect only brain metabolic processes (Chang et al., 1997).

In this critical review, we show in rodents why and how we have used our in vivo fatty acid method to image brain postsynaptic signal transduction involving AA or DHA in response to acute administration of number of agonists and antagonists of G-protein coupled D2-like receptors, 5-HT2A/2C receptors and muscarinic M1,3,5 receptors, and ionotropic NMDA receptors that allow Ca2+ into the cell. Other receptors, also found coupled to cPLA2 or iPLA2 in vitro, might be explored in a similar fashion.

We also quantified in rodents regional neuroplastic changes in AA or DHA signaling following chronic administration of agonist drugs such as nicotine and NMDA, modulators of receptor mediated signaling (mood stabilizers lithium, VPA, CBZ and LTG), inhibitors of the 5-HTT reuptake transporter (e.g. fluoxetine) or modulators of the DAT transporter (amphetamine), genetic models in which brain expression of AA or DHA cascade enzymes or reuptake transporters are knocked out (iPLA2β, COX-2, 5-HTT, DAT), in pathological conditions of LPS- and HIV-1-induced neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity, or following lesioning of the substantia nigra or nucleus basalis (Nariai et al., 1991). Many of these rodent models are relevant to clinically brain disorders (e.g., HIV-1 associated dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, psychiatric disorders including BD, Parkinson’s disease). We also correlated imaging effects with brain expression of PLA2 and COX enzymes, and with brain concentrations of metabolites such as PGE2 and TXB2.

The ability to image brain signal transduction and metabolism involving AA and DHA in animals and humans could be used for examining regional effects of other sensory stimuli as well as of drug-induced neuroreceptor activation in rodent and human subjects, in relation to aging, metabolic disease and various neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases where neurotransmission via AA and DHA likely is disturbed. The fact that brain uptake of tracer is independent of CBF makes our method ideal in many conditions in cases of acute functional or pharmacological activation where blood flow is altered. In these conditions, only values of k* may need to be measured (regional brain radioactivity divided by integrated plasma radioactivity to normalize for dose), since changes in unesterified plasma concentrations are unlikely. To accelerate clinical studies, furthermore, it might be useful to design an 18F AA/DHA ligand (Schmall et al., 1990), as 18F has a radioactive half-life of 110 min compared to the 20 min for [11C], and could be synthesized commercially and delivered to PET centers lacking a cyclotron. A longer half-life with 18F tracer may allow shorter scanning times, and less concern for any late appearing metabolites. Determining ratio of incorporation in a region considered pathological to one not so considered could simplify group distinctions, but would have to be validated experimentally.

One area of AA/DHA imaging research that deserves to be explored relates to evidence that a number of human brain diseases have been associated with a central or peripheral DHA deficiency (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease, depression, schizophrenia, BD) (Conquer et al., 2000; Igarashi et al., 2010; Igarashi et al., 2011; McNamara et al., 2007a; McNamara et al., 2007b). Taken with evidence of an upregulated AA cascade in some of these disorders (see above), such studies suggest an imbalance between DHA and AA signaling that deserves to be explored (Contreras and Rapoport, 2002). In this regard, rodents subjected to n-3 or n-6 fatty acid dietary deficiencies might be used as animal models for neuroimaging. The former show a decreased brain concentration of DHA compensated for by an increased concentration of docosapentaenoic acid n-6 (22:4n-6), which may act as an abnormal second messenger contributing to disturbed behavior (Contreras et al., 2001; DeMar et al., 2006b; Igarashi et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011a).

Highlights.

• The arachidonic (AA) and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acids are released from phospholipid.• We developed an in vivo method in rodents using quantitative autoradiography.• We imaged regional brain AA and DHA signaling and metabolism during neurotransmission.• We imaged the effects of mood stabilizers and neuroinflammation on AA metabolism.• The method can be extended for the use with positron emission tomography in humans.

Figure 7.

Horizontal PET brain images of significant increments in incorporation coefficients k* for arachidonic acid comparing Alzheimer’s disease patients and healthy controls. From (Esposito et al., 2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- BD

bipolar disorder

- CBZ

carbamazepine

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- 5-HT

serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine)

- 5-HTT

serotonin transporter

- IL

interleukin

- LOX

lipoxygenase

- LTG

lamotrigine

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- cPLA2

Ca2+-dependent cytosolic PLA2

- sPLA2

secretory PLA2

- iPLA2

Ca2+-independent PLA2

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- NMDAR

NMDA receptor

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PET

positron emission tomography

- rCBF

regional cerebral blood flow

- rCMRglc

regional cerebral metabolic rate of glucose

- TXB2

thromboxane B2

- VPA

valproic acid

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No author has a financial or other conflict of interest related to this work.

References

- Ahmad S, Fowler LJ, Whitton PS. Effects of acute and chronic lamotrigine treatment on basal and stimulated extracellular amino acids in the hippocampus of freely moving rats. Brain Res. 2004;1029:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Almeida LE, Randall WR, Albuquerque EX. Nicotine at concentrations found in cigarette smokers activates and desensitizes nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in CA1 interneurons of rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:2726–2739. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann B, Born C, Crespo JM, Pomarol-Clotet E, McKenna P. Lamotrigine: when and where does it act in affective disorders? A systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. doi: 10.1177/0269881110376695. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge MS, Zhou M, Lira A, Hen R, Gingrich JA. Early-life blockade of the 5-HT transporter alters emotional behavior in adult mice. Science. 2004;306:879–881. doi: 10.1126/science.1101678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony IC, Bell JE. The Neuropathology of HIV/AIDS. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:15–24. doi: 10.1080/09540260701862037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avison MJ, Nath A, Greene-Avison R, Schmitt FA, Bales RA, Ethisham A, Greenberg RN, Berger JR. Inflammatory changes and breakdown of microvascular integrity in early human immunodeficiency virus dementia. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:223–232. doi: 10.1080/13550280490463532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod J, Burch RM, Jelsema CL. Receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase A2 via GTP-binding proteins: arachidonic acid and its metabolites as second messengers. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:117–123. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod J. Phospholipase A2 and G proteins. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:64–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93873-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal-Price A, Moneer Z, Brown GC. Nitric oxide induces rapid, calcium-dependent release of vesicular glutamate and ATP from cultured rat astrocytes. Glia. 2002;40:312–323. doi: 10.1002/glia.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartus RT, Dean RL, 3rd, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–414. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassant MH, Jazat F, Lamour Y. Tetrahydroaminoacridine and physostigmine increase cerebral glucose utilization in specific cortical and subcortical regions in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:855–864. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Chang L, Seemann R, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic lithium administration potentiates brain arachidonic acid signaling at rest and during cholinergic activation in awake rats. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1553–1562. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic lithium chloride administration to unanesthetized rats attenuates brain dopamine D2-like receptor-initiated signaling via arachidonic acid. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005a;30:1064–1075. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Chang L, Seemann R, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic lithium administration to rats selectively modifies 5-HT2A/2C receptor-mediated brain signaling via arachidonic acid. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005b;30:461–472. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic lithium chloride administration attenuates brain NMDA receptor-initiated signaling via arachidonic acid in unanesthetized rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006a;31:1659–1674. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Chang L, Rapoport SI. Chronic lithium chloride administration to rats elevates glucose metabolism in wide areas of brain, while potentiating negative effects on metabolism of dopamine D2-like receptor stimulation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006b;187:303–311. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Villacreses NE, Langenbach R, Ma K, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Resting and arecoline-stimulated brain metabolism and signaling involving arachidonic acid are altered in the cyclooxygenase-2 knockout mice. J Neurochem. 2006c;96:669–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Villacreses NE, Chen M, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic carbamazepine administration reduces NMDA receptor-initiated signaling via arachidonic acid in rat brain. Biol Psychiatry. 2007a;62:934–943. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Villacreses NE, Lee H-J, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Flurbiprofen, a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, reduces the brain arachidonic acid signal in response to the cholinergic muscarinic, arecoline, in awake rats. Neurochem Res. 2007b;32:1857–1867. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Villacreses NE, Lee HJ, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic lithium administration attenuates up-regulated brain arachidonic acid metabolism in a rat model of neuroinflammation. J Neurochem. 2007c;102:761–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Chang L, Chen M, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic administration of valproic acid reduces brain NMDA signaling via arachidonic acid in unanesthetized rats. Neurochem Res. 2008a;33:1373–1383. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9700-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Chang L, Chen M, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Chronic carbamazepine admistration attenuates dopamine D2-like receptor-initiated signaling via arachidonic acid in rat brain. Neurochem Res. 2008b;33:1373–1383. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9595-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Fox MA, Chang L, Bell JM, Greenstein D, Chen M, Murphy DL, Rapoport SI. Imaging elevated brain arachidonic acid signaling in unanesthetized serotonin transporter (5-HTT)-deficient mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009a;34:1695–1709. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Nguyen HN, Chang L, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Acute but not chronic donepezil administration increases muscarinic receptor-mediated brain signaling involving arachidonic acid in unanesthetized rats. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009b;17:369–382. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Kim HW, Chen M, Ma K, Rapoport SI, Murphy RC, Farias SE. Lithium modifies brain arachidonic and docosahexaenoic metabolism in rat lipopolysaccharide model of neuroinflammation. J Lipid Res. 2010a;51:1049–1056. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Basselin M, Rosa AO, Ramadan E, Cheon Y, Chang L, Chen M, Greenstein D, Wohltmann M, Turk J, Rapoport SI. Imaging decreased brain docosahexaenoic acid metabolism and signaling in iPLA2β (VIA)-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 2010b;51:3166–3173. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M008334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Ramadan E, Chen M, Rapoport SI. Anti-inflammatory effects of chronic aspirin on brain arachidonic acid metabolites. Neurochem Res. 2011a;36:139–145. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0282-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Basselin M, Ramadan E, Igarashi M, Chang L, Chen M, Kraft AD, Harry GH, Rapoport SI. Imaging upregulated brain arachidonic acid metabolism in HIV-1 transgenic rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011b;31:486–493. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Bayon Y, Hernandez M, Alonso A, Nunez L, Garcia-Sancho J, Leslie C, Sanchez Crespo M, Nieto ML. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is coupled to muscarinic receptors in the human astrocytoma cell line 1321N1: characterization of the transducing mechanism. Biochem. J. 1997;323:281–287. doi: 10.1042/bj3230281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazinet RP, Rao JS, Chang L, Rapoport SI, Lee HJ. Chronic carbamazepine decreases the incorporation rate and turnover of arachidonic acid but not docosahexaenoic acid in brain phospholipids of the unanesthetized rat: relevance to bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006a;59:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazinet RP, Weis MT, Rapoport SI, Rosenberger TA. Valproic acid selectively inhibits conversion of arachidonic acid to arachidonoyl-CoA by brain microsomal long-chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetases: relevance to bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006b;184:122–129. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneyto M, Kristiansen LV, Oni-Orisan A, McCullumsmith RE, Meador-Woodruff JH. Abnormal glutamate receptor expression in the medial temporal lobe in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1888–1902. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Dodd S, Kauer-Sant'anna M, Malhi GS, Bourin M, Kapczinski F, Norman T. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome: implications for a dopamine hypothesis of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2007:41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler AS, Li S, Nicol R, Walsh MJ. Carbamazepine is an inhibitor of histone deacetylases. Life Sci. 2005;76:3107–3115. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee AK, Chang L, Seeman R, Lee HJ, Bazinet RP. D2 but not D1 dopamine receptor stimulation augments brain signaling involving arachidonic acid in unanesthetized rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:735–742. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]