Abstract

Background

Identify factors associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) screening test preference and examine the association between test preference and test completed.

Methods

Patients (N=1224) were 50-70 years, at average CRC risk, and overdue for screening. Outcome variables were preference for fecal occult blood test (FOBT), colonoscopy (COL), sigmoidoscopy (SIG), or barium enema (BE) measured by telephone survey, and concordance between test preference and test completed assessed using medical records.

Results

Thirty-five percent preferred FOBT, 41.1% COL, 12.7% SIG, and 5.7% BE. Preference for SIG or COL was associated with having a physician recommendation, greater screening readiness, test-specific self-efficacy, greater CRC worry, and perceived pros of screening. Preference for FOBT was associated with self-efficacy for doing FOBT. Participants who preferred COL were more likely to complete COL compared with those who preferred another test. Of those screened, only 50% received their preferred test. Those not receiving their preferred test most often received COL (52%).

Conclusion

Lack of concordance between patients’ preferences and test completed suggests that patients’ preferences are not well incorporated into screening discussions and test decisions, which could contribute to low screening uptake.

Practice Implications

Physicians should acknowledge patients’ preferences when discussing test options and making recommendations, which may increase patients’ receptivity to screening.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, screening, patient education, decision making

1. Introduction

Recommendations from the 2010 National Institute of Health State of the Science Conference “Enhancing Use and Quality of Colorectal Cancer Screening” state that there is a need to better understand the association between patients’ preferences and use of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening tests 1. This recommendation stems largely from the fact that national organizations endorse multiple options for the early detection and prevention of CRC 2,3. The most commonly recommended modalities include the fecal occult blood test (FOBT), fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and colonoscopy (COL), but other tests, including flexible sigmoidoscopy (SIG), double contrast barium enema (BE), and virtual colonoscopy (V-COL) also are considered options for screening. Although CRC screening rates have gradually increased over the past 10 years, they remain lower than those for other cancers 4,5. Incorporating patients’ preferences into physicians’ screening recommendations may be a way to increase screening rates.

A number of studies have described variation in patients’ preferences for CRC screening tests 6-15, and some have examined socio-demographic characteristics associated with preferences 8,9,11-16. Studies are consistent in reporting that stool blood testing and endoscopy (usually COL) are most often cited as the preferred options. With a few exceptions 7,13, studies also have been consistent in reporting that socio-demographic characteristics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education are not associated with test preferences 9,11,12,14-16.

Associations between test preferences and test characteristics, such as accuracy, convenience, and discomfort, also have been examined 6-9,11,13-16. Concern about discomfort and convenience were consistently associated with a preference for FOBT 6-9,11,13,14 while test accuracy was consistently associated with a preference for SIG or COL 7,8,11,13-16. Screening-related factors such as physician recommendation and prior screening also have been examined in relation to test preferences, but results have been inconsistent 6,8-13,16.

With the exception of Powell et al. 12, very few studies have examined the associations between test preference and psychosocial factors such as perceived risk and self-efficacy, and most of the others examined only one or two constructs 6,8,9,16. Only three studies have examined the relation between CRC screening test preference and the CRC test completed 15,17 or ordered by a physician 14. Wolf et al. 15 found that approximately 40% of their study sample did not receive the test they said they preferred, and Ruffin et al. 17 found only modest correlations between preferred test and test received. Although Schroy et al. 14 did not examine completion of screening, they found that 40% of the time physicians did not order the test their patient preferred.

Because psychosocial factors may influence CRC screening test preferences which, in turn, may influence uptake of CRC screening, we examined the associations between a number of psychosocial variables and CRC test preference. We also assessed the concordance between baseline CRC screening test preference and the type of test completed.

2. Methods

Data from these analyses are from a 5-year randomized behavioral intervention trial designed to increase CRC screening 18. The trial was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Texas School of Public Health (UTSPH) and is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01084746).

2.1 Selection and recruitment of study population

The study was conducted at Kelsey-Seybold Clinic, the largest multi-specialty medical organization in Houston, Texas, with 21 locations. Eligible patients had received primary care at the clinic within the past year; were between 50-70 years of age; never had CRC or polyps; had never been screened or were due for CRC screening according to American Cancer Society guidelines in effect at the time of the study 19; had not had a physical exam within the past year; did not have a prior diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis; and were able to speak English.

Between January 2004 and February 2006, staff at the Kelsey Research Foundation mailed invitation letters to potentially eligible patients who were identified monthly from the clinic’s administrative database. A contact telephone number was included in the letter so that recipients could call and decline participation. Staff at the Foundation telephoned patients who did not decline to introduce the study, confirm eligibility, and enroll them. Invitees were considered non-respondents if they could not be reached after six calls that were made during different times of the day and days of the week. Contact information for interested patients was sent to the UTSPH research staff who conducted baseline telephone surveys. Of 1384 patients enrolled by Foundation staff, 1224 (88%) completed a baseline survey; this group constituted the analysis sample for this study. A detailed description of the process of recruitment and enrollment,, including a CONSORT diagram, is published elsewhere 18.

2.2 Data collection and study design

After administration of the baseline survey, participants were randomized to one of three study groups stratified by gender and past CRC screening status (ever screened vs. overdue for screening). The tailored intervention group participated in an interactive, tailored computer program; the website group viewed general information about CRC screening from a publicly available website, Screen for Life, which is the national CRC awareness campaign from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the survey-only control group received no additional information about CRC screening. As part of the study, all participants completed a wellness visit and exam. At 12-month follow-up, medical records were reviewed to collect CRC screening utilization data. Additional details of the intervention trial and outcome results, including factors associated with CRC screening adherence, are reported elsewhere 18.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1. Outcome variables

The outcome used to examine correlates of CRC test preference was self-reported CRC screening test preference as measured on the baseline survey. Respondents were asked: “Now that you have heard descriptions of all four colon cancer screening tests, which one would you prefer to get, if you had a choice?” Responses included FOBT, SIG, COL, BE, and don’t know/not sure.

The other outcome was concordance between test preference at baseline and type of CRC test received (FOBT, SIG, COL, BE) 12 months post-intervention. Test received was ascertained from the clinic’s medical record and administrative databases. For patients who completed more than one screening test during the study period, we counted the first test completed.

2.3.2. Correlates

Because there is scant research on the psychosocial correlates of CRC test preferences, we selected variables from the baseline survey that have been shown in the literature to be associated with CRC screening 20,21. Patient characteristics and the categories used for analytic purposes were: age (continuous); race (White, African American, Hispanic/other); gender (male/female); marital status (married/partnered, not married/divorced/widowed); employment status (employed, not employed/retired/disabled); education (high school graduate or less, some college, college graduate, post-college education); and family history of CRC (yes, no). All participants in this study were insured; therefore, we did not include insurance status as a patient characteristic 18.

Screening-related factors included prior CRC screening (yes or no), type of test received (FOBT, SIG, COL, BE), physician recommendation, stage of change or readiness to be screened, and preference for involvement in medical decision making. Prior screening was assessed with a standard set of measures 22. Patients’ were asked if they had ever received a physician’s recommendation to be screened for CRC (yes or no) as well as whether they received a test-specific recommendation for FOBT, SIG, COL, or BE. Stage of readiness to get CRC screening was measured as precontemplation (not thinking about testing), contemplation, or preparation for action (committed to getting tested). Contemplation was measured using three questions: need to consider testing, think I should but am not quite ready, and think I will probably get tested. We used the five-point Control Preferences Scale 23 to characterize respondents’ beliefs about how medical decisions should be made. We collapsed the scale into three categories reflecting a preference for a patient-based, shared, or physician-based decision 7,24. Participants who did not respond to this question were coded as having an unknown preference.

Psychosocial factors included participants’ test-specific self-efficacy, comparative perceived risk, worry about CRC, CRC knowledge, and perceived pros and cons of CRC screening. Test-specific self-efficacy was assessed with four items reflecting the degree to which respondents felt confident in completing each test (FOBT, SIG, COL, BE). The four response categories were dichotomized for analysis (very confident, confident /not very/not at all confident). Comparative perceived risk was measured with a single item from the 2003 Health Information and National Trends Survey (less likely, equally likely, or more likely to develop CRC compared with others my age). Worry about CRC was measured with a single item (never, rarely, sometimes, most of the time, all of the time). Knowledge was measured with four items (true/false). Perceived pros (α=0.75, items = 8) and cons (α=0.78, items = 10) for getting CRC screening were measured using validated multi-item scales with a four-point response scale ranging from “not very important” to “very important” 25. We calculated mean scores for knowledge, as well as perceived pros and cons of CRC screening.

2.4 Data Analysis

Univariable associations between baseline CRC test preference (FOBT, COL, SIG or BE) and categorical independent variables were analyzed using chi-square contingency tables; continuous variables were analyzed using t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Variables that were associated with test preference in univariable analyses at p<.10 were included in multivariable analyses to identify factors independently associated with preference stated at baseline. As recommended by Hosmer and Lemeshow, we used a less conservative p value (p<0.10) to select variables for inclusion in the multinomial analyses in order to reduce the possibility that we would exclude variables that could be important 26. We then performed a multinomial analysis using three outcome variables: FOBT, SIG, and COL. We used FOBT as the referent category to compare COL vs. FOBT and SIG vs. FOBT. We then used SIG as the referent category to compare COL vs. SIG. Results were summarized with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. We excluded patients with a baseline preference for BE from the multinomial analysis because so few respondents indicated it as a test preference (6%). In the multivariable analyses, worry about CRC was collapsed into two categories (never/rarely, sometimes/most of the time/all of the time), and stage of readiness for CRC screening was analyzed as a continuous variable.

To evaluate concordance between baseline CRC test preference and type of test completed, we compared each patient’s stated preference at baseline to their test completion by 12 months. This analysis included having an unknown preference at baseline and receiving no test by 12 months. Baseline preferences included FOBT, COL, SIG, BE and unknown. Completion categories included FOBT, COL, SIG and no test (only 2 patients had received BE by 12 months). Comparisons between stated preferences and test completion were done using chi-square analyses.

3. Results

3.1 Description of the sample

The mean age of study participants was 55.5 years; the sample was predominantly African American or white, female, married, employed, and had at least a high school education (Table 1, columns 1 and 2). Only 7% reported a family history of CRC. Approximately half had previously been screened for CRC and were overdue, and approximately half reported that CRC screening had ever been recommended by a physician. Patients reported all CRC tests received, thus the total number of specific tests completed or recommended exceeds the total reporting having ever been screened or recommended for screening (Table 1 footnote). About half stated that they preferred to make medical decisions themselves while 40% preferred that medical decisions be shared; only 10% preferred that a physician make medical decisions. Over one-third said they were committed to getting tested; less than 10% were not thinking about getting tested. Patients reported that they were “very confident” (had high self-efficacy) that they could complete FOBT compared with the other tests. Over half of the sample stated that they were equally likely to develop CRC compared with others their age. The majority reported that they rarely or never worried about CRC. Mean knowledge scores reflected some knowledge about CRC; mean scores were high for perceived pros and low for perceived cons of CRC screening.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Baseline Test Preference: Univariable Analyses (n=1,224)

| Total sample characteristics (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | % | FOBT n=425 34.7% |

COL n=503 41.1% |

SIG n=155 12.7% |

BE n=70 5.7% |

No preference n=71 5.8% |

p-valueb | |

| Age - mean (SD) | 55.6 (4.4) | 55.2 (4.2) | 55.7 (4.4) | 56.0 (4.4) | 55.3 (4.8) | 56.5 (4.4) | 0.702 | |

| Race | 0.286 | |||||||

| White | 428 | 35.0 | 38.8 | 39.0 | 11.7 | 3.0 | 7.5 | |

| African American | 576 | 47.1 | 33.2 | 42.9 | 12.8 | 7.6 | 3.7 | |

| Hispanic/other | 220 | 18.0 | 30.9 | 40.4 | 14.6 | 5.9 | 8.2 | |

| Gender | 0.255 | |||||||

| Female | 725 | 59.2 | 36.3 | 40.0 | 13.7 | 5.9 | 4.1 | |

| Male | 499 | 40.8 | 32.5 | 42.7 | 11.2 | 5.4 | 8.2 | |

| Marital status | 0.950 | |||||||

| Married/partnered | 746 | 60.9 | 34.4 | 40.8 | 12.9 | 5.4 | 6.6 | |

| Not married/divorced/widowed | 473 | 38.6 | 35.3 | 41.9 | 12.5 | 6.3 | 4.0 | |

| Employment status | 0.926 | |||||||

| Employed (Full and/or Part time) | 988 | 80.7 | 34.6 | 41.3 | 13.0 | 5.6 | 5.6 | |

| Not employed (includes retired) | 228 | 18.6 | 34.7 | 41.2 | 11.8 | 6.6 | 5.7 | |

| Educational attainment | 0.418 | |||||||

| < High school or HS Grad | 305 | 24.9 | 33.8 | 42.0 | 12.1 | 6.6 | 5.6 | |

| Some college | 412 | 33.7 | 36.2 | 41.3 | 11.2 | 6.6 | 4.9 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 254 | 20.8 | 35.8 | 39.4 | 11.4 | 5.5 | 7.9 | |

| Post-college (graduate degree) | 246 | 20.1 | 32.5 | 41.9 | 17.5 | 3.7 | 4.5 | |

| Family history of CRC | 0.021 | |||||||

| Yes | 85 | 6.9 | 29.4 | 56.5 | 7.1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| No | 1139 | 93.1 | 35.1 | 40.0 | 13.1 | 5.9 | 6.0 | |

| Ever had CRC screening test | 0.186 | |||||||

| Yes | 628 | 51.3 | 32.6 | 43.5 | 12.7 | 6.1 | 5.1 | |

| No | 596 | 48.7 | 36.9 | 38.6 | 12.6 | 5.4 | 6.5 | |

| FOBTc | 388 | 61.8 | 36.1 | 43.0 | 11.6 | 5.7 | 3.6 | 0.110 |

| COLc | 135 | 22.0 | 27.4 | 50.4 | 11.1 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 0.152 |

| SIGc | 190 | 30.3 | 27.4 | 45.3 | 19.5 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 0.003 |

| BEc | 245 | 39.0 | 32.7 | 40.8 | 9.8 | 10.6 | 6.1 | 0.399 |

| MD ever recommended any CRC screening test | <0.001 | |||||||

| Yes | 616 | 50.3 | 29.1 | 45.9 | 15.1 | 5.0 | 4.9 | |

| No | 608 | 49.7 | 40.5 | 36.2 | 10.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | |

| FOBTd | 78 | 12.7 | 44.9 | 37.2 | 12.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 0.012 |

| COLd | 319 | 51.8 | 24.4 | 53.9 | 14.1 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 0.001 |

| SIGd | 59 | 9.6 | 25.4 | 42.4 | 23.7 | 6.8 | 1.7 | 0.163 |

| BEd | 10 | 1.6 | 40.0 | 50.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.791 |

| Non-specific recommendationd | 148 | 24.0 | 31.8 | 35.1 | 16.2 | 8.8 | 8.1 | 0.090 |

| Preference for decision making | 0.078 | |||||||

| Patient-based | 599 | 48.9 | 38.7 | 38.1 | 13.5 | 4.3 | 5.3 | |

| Shared | 499 | 40.8 | 30.7 | 44.7 | 12.2 | 7.0 | 5.4 | |

| Doctor-based | 119 | 9.7 | 32.8 | 41.2 | 10.9 | 7.6 | 7.6 | |

| Stage of readiness for CRC screening at baseline | <0.001 | |||||||

| Not thinking of getting tested (PC) | 95 | 7.8 | 59.0 | 16.8 | 9.5 | 8.4 | 6.3 | |

| Considering getting tested (C) | 219 | 17.9 | 39.7 | 34.3 | 11.0 | 7.3 | 7.8 | |

| Think I should get tested (C) | 182 | 14.9 | 45.1 | 30.2 | 8.8 | 9.9 | 6.0 | |

| Probably will get tested (C) | 268 | 2.2 | 33.2 | 46.3 | 14.2 | 3.7 | 2.6 | |

| I am committed to getting tested (P) | 456 | 3.7 | 24.3 | 50.9 | 14.9 | 4.0 | 5.9 | |

| Test specific self efficacy | ||||||||

| FOBT (very confident) | 719 | 59.4 | 37.6 | 40.1 | 12.0 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 0.107 |

| COL (very confident) | 602 | 49.5 | 27.1 | 52.3 | 11.8 | 4.0 | 4.8 | <0.001 |

| SIG (very confident) | 547 | 44.7 | 28.5 | 44.8 | 16.3 | 4.8 | 5.7 | <0.001 |

| BE (very confident) | 501 | 40.9 | 31.3 | 45.1 | 11.8 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 0.036 |

| Comparative risk | 0.005 | |||||||

| Less likely to develop CRC | 336 | 27.4 | 42.9 | 35.4 | 12.5 | 4.5 | 4.8 | |

| Equally likely to develop CRC | 641 | 52.4 | 33.2 | 42.3 | 13.6 | 6.2 | 4.7 | |

| More likely to develop CRC | 215 | 17.6 | 27.4 | 47.0 | 11.6 | 6.5 | 7.4 | |

| Worry about CRC | <0.001 | |||||||

| Never | 510 | 41.7 | 40.8 | 35.1 | 12.9 | 5.7 | 5.5 | |

| Rarely | 396 | 32.4 | 35.9 | 42.7 | 12.4 | 4.3 | 4.8 | |

| Sometimes | 262 | 21.4 | 26.0 | 47.0 | 12.2 | 8.0 | 6.9 | |

| Most of the time | 31 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 67.7 | 12.9 | 9.7 | 3.2 | |

| All the time | 15 | 1.2 | 13.3 | 60.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | |

| CRC knowledge | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.9) | 0.191 | |

| Pros of CRC screening | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.3 (0.5) | 0.041 | |

| Cons of CRC screening | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.6) | 0.876 | |

Missing values ranged from zero for age to 34 CRC test-specific MD recommendation among those answering “yes” to MD ever recommended CRC screening test.

BE and “no preference” are excluded from chi square analyses. P-values <0.10 are considered statistically significant for purposes of variable selection to the multivariate model.

Test-specific percentages reflect percent of those answering “yes” to general screening question (n=628). P-value reflects comparisons between those ever having specific colon cancer screening test (yes/no) and baseline preferences. Categories are not mutually exclusive; participants could respond “yes” to more than one test.

Test-specific percentages reflect percent of those answering “yes” to general recommendation question (n=616). P-value reflects comparisons between those ever having a physician recommendation for that specific test (yes/no) and baseline preferences. Categories are not mutually exclusive; participants could respond “yes” to more than one test recommendation.

3.2 Factors associated with baseline CRC screening preference: Univariable analysis

Most patients stated a test preference: 34.7% indicated a preference for FOBT, 41.1% for COL, 12.7% for SIG, 5.7% for BE, and 5.8% did not report a preference. Factors statistically significantly associated at p<.10 with baseline test preference for COL, SIG, or FOBT in univariable analyses were family history, ever had CRC screening with SIG, physician recommendation for any CRC test, FOBT, and COL, preference for decision making, stage of readiness for CRC screening, test-specific self-efficacy for FOBT, COL or SIG, comparative perceived risk, worry, and perceived pros of CRC screening (Table 1, columns 3-6).

3.3 Factors associated with baseline CRC screening preference: Multivariable analysis

Table 2 shows the multivariable logistic regression results for factors associated with preference for FOBT, COL, or SIG, always using the less invasive test as the referent. Because prior use of SIG was significantly associated with preference, we also included prior use of FOBT and COL in the multivariable models. Likewise, because physician recommendation for FOBT and COL were significant, we included recommendation for SIG. We did not include prior recommendation for any test (i.e., “ever received a recommendation”) or for a non-specific recommendation because of the high correlations with test-specific recommendations. The factors that remained statistically significantly associated in at least one of the multinomial regression models were prior use of CRC screening with SIG, prior test-specific physician recommendation, stage of readiness, test-specific self-efficacy, worry about CRC, and perceived pros of CRC screening.

Table 2.

Factors associated with stated preferences for FOBT, COL and SIG

| COL vs. FOBT | SIG vs. FOBT | COL vs. SIG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family history (yes vs. no) | 1.08 (0.61-1.90) | 0.46 (0.17-1.21) | 2.36 (0.94-5.93) |

| Prior CRC test (yes vs. no)a | |||

| FOBT | 1.01 (0.73-1.39) | 0.71 (0.45-1.12) | 1.41 (0.91-2.20) |

| SIG | 1.01 (0.93-1.09) | 0.58 (0.37-0.93)* | 1.73 (1.08-2.75)* |

| COL | 1.04 (0.88-1.23) | 1.01 (0.81-1.26) | 1.03 (0.88-1.21) |

| Physician recommendation (yes vs. no)a | |||

| FOBT | 0.59 (0.34-1.03) | 0.68 (0.32-1.47) | 0.86 (0.40-1.87) |

| SIG | 1.75 (0.87-3.56) | 2.52 (1.09-5.81)* | 0.69 (0.32-1.49) |

| COL | 2.28 (1.62-3.22)** | 1.78 (1.12-2.83)* | 1.28 (0.84-1.96) |

| Preference for decision making | |||

| Doctor-based | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Shared | 1.24 (0.74-2.09) | 1.13 (0.55-2.35) | 1.10 (0.54-2.22) |

| Patient-based | 0.89 (0.53-1.49) | 1.25 (0.61-2.56) | 0.71 (0.35-1.42) |

| Stage of readinessb | 1.33 (1.19-1.49)** | 1.34 (1.15-1.57)** | 0.99 (0.85-1.16) |

|

Self-efficacy (very confident vs. less confident) |

|||

| FOBT confidence | 0.48 (0.34-0.68)** | 0.48 (0.30-0.76)* | 1.01 (0.64-1.58) |

| SIG confidence | 1.10 (0.75-1.62) | 3.45 (2.03-5.87)** | 0.32 (0.19-0.53)** |

| COL confidence | 2.82 (1.92-4.13)** | 0.70 (0.42-1.17) | 4.03 (2.44-6.66)** |

| Comparative perceived risk | |||

| About average | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Less than average | 0.83 (0.59-1.16) | 0.87 (0.55-1.37) | 0.95 (0.61-1.48) |

| More than average | 1.27 (0.84-1.92) | 1.01 (0.57-1.80) | 1.25 (0.73-2.14) |

|

CRC worry (sometimes/most of the time/all the time vs. rarely/never) |

1.96 (1.36-2.84)** | 1.71 (1.05-2.78)* | 1.15 (0.74-1.79) |

| Pros of CRC screening | 1.62 (1.13-2.33)* | 1.04 (0.65-1.66) | 1.56 (0.98-2.48) |

COL (colonoscopy); CRC (colorectal cancer); FOBT (fecal occult blood test); SIG (sigmoidoscopy).

p<0.05

p<0.001.

Respondents could report having had more than one test and/or having had recommendations for more than one test.

Rate ratio applies to each one-step increase in stage of change, i.e. for each increase in stage, there is a 33% increase for COL vs. FOBT and a 34% increase for SIG vs. FOBT.

Three factors were consistently and positively associated with a preference for one of the more invasive tests. Patients whose physician recommended SIG or COL were more likely to prefer those tests to FOBT as were patients who reported being more committed to screening and those who reported being more worried about CRC. Higher scores on the perceived pros of screening were associated with a preference for COL over FOBT and SIG.

Greater self-efficacy for completing a specific test was statistically significantly associated with a preference for that test. For example, those with high self-efficacy for FOBT were more likely to prefer FOBT to COL or SIG while those with high self-efficacy for COL were more likely to prefer COL to FOBT or SIG. Interestingly, prior experience with SIG was associated with a preference for either of the other tests.

3.4 Baseline test preference and test utilization

Regardless of baseline test preference, most patients did not get screened 18. At 12-month follow-up, over 65% had no evidence in the medical record or administrative databases of receiving any CRC screening test; 9.7% had received FOBT, 22.3% had received COL, less than 2% had received SIG; and only 3 patients received BE.

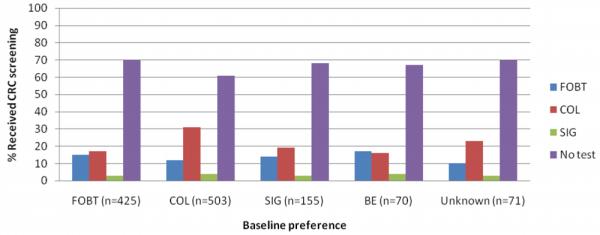

The pattern of association between baseline test preference and test completed was statistically significant (Figure 1). These results were driven largely by the association between baseline preference for COL and receipt of COL. To explore this association further, we examined preference for COL compared with other tests in relation to screening at 12-month follow-up. Participants who preferred COL at baseline were significantly more likely to complete COL by 12-month follow-up compared with those who had a preference for any other test (χ2=9.98, p=0.002). When we restricted the analysis to those who had been screened by 12 months (N=448 or 34% of the sample), 51.3% (N=215) received the test they indicated they preferred at baseline. Of those who did not receive the test they preferred, the majority (51.9%) received COL.

Figure. Association between baseline test preferences and receipt of CRC screening at 12-months.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Consistent with other studies, we found that most patients preferred COL or FOBT to the other CRC tests and that socio-demographic characteristics were not associated with test preferences 6-15. Collectively, these findings suggest that offering only the options of FOBT and COL would be acceptable to most patients. Moreover, the fairly even split in the percentage of patients who prefer those two tests supports the view that both tests should be offered to patients.

To our knowledge, ours is one of the few studies to examine psychosocial factors associated with test preference. Like Powell et al. 12 we found an association between greater self-efficacy for screening with COL and a preference for that test. However, unlike Powell et al., we also found that greater self-efficacy for FOBT and SIG were associated with a preference for those tests. Powell et al. also found that scoring high on the salience or importance of screening was associated with a preference for COL over other options, and we found that higher scores on the pros of screening were associated with a preference for COL. In our study, patients at a higher stage of readiness to get tested also preferred SIG or COL to other options. It may be that as patients learn about the benefits of screening and its importance in preventing CRC, they are more likely to make a commitment to get screened and to choose a test that, although invasive, can prevent CRC. Increasing support for COL by primary care physicians as compared with other CRC screening tests may also contribute to patient preferences for this option 27. In contrast, those least interested in getting screened were more likely to choose FOBT, a test that requires less planning and preparation, is more convenient to do, and is less invasive than SIG or COL.

Like two other studies 11,12, we found an association between the test patients said their physician recommended and preference for that test. However, one study 8 found that one-third of the sample said they would adhere to their choice even if their physician recommended an alternative test. Our finding that only 10% of our sample favored having a physician make their medical decisions supports the view that while patients may value their physician’s opinion, they want to have a voice in making medical decisions. These findings underscore the need for physicians to be aware of and consider patients’ preferences when making recommendations. Our findings also support educating patients about the importance of advocating for their own preferences in visits with their physicians.

With the exception of SIG, we found no association and no consistent pattern in the odds ratios between prior screening with a specific test and preference for future screening with that test. In fact, counter to what might be expected, prior experience with SIG was associated with a preference for either of the other tests, suggesting that having a SIG did not reinforce a commitment to future screening with SIG. Likewise, findings from other studies also have been inconsistent with respect to the association between prior screening and preference with some studies finding a positive association 8-10,16, some finding no association 6,11,13, and some finding different patterns depending on the test 7,12. The lack of association between prior screening with COL or FOBT and a preference for those tests together with the positive association between physician recommendation and a preference for the recommended test suggests that prior screeners may be open to considering other test options. However, our finding that patients preferred the test that they were more confident they could complete suggests that physicians need to take patients’ perceived confidence into consideration when they make a test recommendation.

Although consistent with other studies 14,15,17, our potentially most concerning finding was the lack of association between patients’ stated test preference at baseline and the type of test they received (if any). This discrepancy could contribute to the overall low uptake of screening we observed, and future studies should investigate whether patients who do not feel that their test preferences are supported by their physicians are less likely to be adherent to CRC screening recommendations and guidelines. Recent studies have found that the extent of informed decision making for CRC screening during primary care visits is minimal 28,29. Recent studies, including one conducted with a subsample of participants in this intervention trial, also have documented that primary care physicians tend to recommend COL above other screening tests regardless of a patient’s expressed preference 27,29,30. If COL continues to be the most commonly recommended CRC screening test in primary care 27,29,30, educational programs that emphasize the benefits of COL may increase patients’ receptivity to it, particularly if they are supported by a discussion with the provider and by systems that facilitate scheduling and completing the test.

Our findings need to be interpreted in the context of several limitations. The study setting was a large multi-specialty group practice where patients have relatively equal access to all CRC tests; therefore, our results may not generalize to settings without access to all test options. In addition, the study design used to assess associations between preference and psychosocial and other factors was cross-sectional; therefore, inferences about the direction of influence cannot be made. Finally, test preference was only assessed at baseline, and it is possible that it changed after patients met with their physician. If this were the case, it could explain why patients who preferred COL were more likely to be screened compared with those who preferred other tests and why patients who preferred FOBT received COL.

4.2 Conclusion

Patients’ at a higher stage of readiness for CRC screening, who reported more pros to screening, and who expressed more worry about CRC preferred one of the more invasive tests. Although in general, patients preferred the test their physician recommended, lack of concordance between patients’ preferences and test completed suggests that patients’ preferences are not well incorporated into screening discussions and test decisions. Ensuring that patients understand the benefits of screening and that they receive information about what each test entails may increase their self-efficacy and make it more likely that they will complete the test they choose.

4.3. Practice Implications

Primary care physicians need to be aware that patients’ preferences for CRC screening tests differ. Assessing and acknowledging these preferences when making CRC screening recommendations could positively impact patient adherence. In addition, educating patients about the benefits of screening and providing support for completing the test they choose may make patients more receptive to CRC screening.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from National Cancer Institute, R01 097263 (PI: Sally Vernon). Dr. McQueen is supported by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant, CPPB-113766.

Reference List

- 1.Steinwachs D, Allen JD, Barlow WE, Duncan RP, Egede LE, Friedman LS, et al. NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Enhancing Use and Quality of Colorectal Cancer Screening. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2010;27:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society [accessed November 9, 2010];Colorectal cancer early detection. Available from URL: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003170-pdf.pdf.

- 3.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;149:627–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klabunde CN, Lanier D, Meissner HI, Breslau ES, Brown ML. Improving colorectal cancer screening through research in primary care settings. Medical Care. 2008;46:S1–4. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181805e2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meissner HI, Breen NL, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the US. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15:389–394. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almog R, Ezra G, Lavi I, Rennert G, Hagoel L. The public prefers fecal occult blood test over colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2008;17:430–7. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328305a0fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawley ST, Volk RJ, Krishnamurthy P, Jibaja-Weiss M, Vernon SW, Kneuper S. Preferences for colorectal cancer screening among racial/ethnically diverse primary care patients. Medical Care. 2008;46:S10–6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d932e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBourcy AC, Lichtenberger S, Felton S, Butterfield KT, Ahnen DJ, Denberg TD. Community-based preferences for stool cards versus colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:169–74. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0480-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janz NK, Lakhani I, Vijan S, Hawley ST, Chung LK, Katz SJ. Determinants of colorectal cancer screening use, attempts, and non-use. Preventive Medicine. 2007;44:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leard LE, Savides TJ, Ganiats TG. Patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening. Journal of Family Practice. 1997;45:211–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ling BS, Moskowitz MA, Wachs D, Pearson B, Schroy PC., III Attitudes toward colorectal cancer screening tests: a survey of patients and physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:822–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell AA, Burgess DJ, Vernon SW, Griffin JM, Grill JP, Noorbaloochi S, et al. Colorectal cancer screening mode preferences among US veterans. Preventive Medicine. 2009;49:442–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroy PC, III, Lal S, Glick JT, Robinson PA, Zamor P, Heeren TC. Patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening: how does stool DNA testing fare? The American Journal of Managed Care. 2007;13:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroy PC, Emmons K, Peters E, Glick JT, Robinson PA, Lydotes MA, et al. The impact of a novel computer-based decision aid on shared decision making for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Medical Decision Making. 2010;31:93–107. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10369007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf RL, Basch CE, Brouse CH, Shmukler C, Shea S. Patient preferences and adherence to colorectal cancer screening in an urban population. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:809–811. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pignone MP, Bucholtz D, Harris R. Patient preferences for colon cancer screening. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14:432–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruffin MT, Fetters MD, Jimbo M. Preference-based electronic decision aid to promote colorectal cancer screening: results of a randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine. 2007;45:267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vernon SW, Bartholomew LK, McQueen A, Bettencourt JL, Greisinger A, Coan SP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored computer-delivered intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening: sometimes more is just the same. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;41:284–299. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith RA, von Eschenbach A, Wender R, Levin B, Byers T, Rothenberger D, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:38–75. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill J, Burgess DJ, van Ryn M, Fisher DA, et al. The interrelationships between and contributions of background, cognitive, and environmental factors to colorectal cancer screening adherence. Cancer Causes & Control. 2010;21:1357–68. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vernon SW, McQueen A. Colorectal cancer screening. In: Holland Jimmie C., Breitbart William S., Jacobsen Paul B., Lederberg Marguerite S., Loscalzo Matthew J., McCorkle Ruth., editors. Psycho-oncology. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; New York,NY: 2010. pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vernon SW, Meissner HI, Klabunde CN, Rimer BK, Ahnen D, Bastani R, et al. Measures for ascertaining use of colorectal cancer screening in behavioral, health services, and epidemiologic research. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2004;13:898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: What role do patients really want to play? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45:941–950. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lantz PM, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Schwartz K, Liu L, Lakhani I, et al. Satisfaction with surgery outcomes and the decision process in a population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Health Services Research. 2005;40:745–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McQueen A, Tiro JA, Vernon SW. Construct validity and invariance of four factors associated with colorectal cancer screening across gender, race, and prior screening. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17:2231–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 2000. pp. 1–367. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klabunde CN, Lanier D, Nadel MR, McLeod C, Yuan G, Vernon SW. Colorectal cancer screening by primary care physicians: recommendations and practices, 2006-2007. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ling BS, Schoen RE, Trauth JM, Wahed AS, Eury T, Simak DM, et al. Physicians encouraging colorectal screening: a randomized controlled trial of enhanced office and patient management on compliance with colorectal cancer screening. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169:47–55. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McQueen A, Bartholomew LK, Greisinger AJ, Medina GG, Hawley ST, Haidet P, et al. Behind Closed Doors: Physician-Patient Discussions About Colorectal Cancer Screening. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:1228–35. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1108-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lafata JE, Divine G, Moon C, Williams LK. Patient-physician colorectal cancer screening discussions and screening use. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]