In the U.S., racial/ethnic health disparities remain substantial and persistent (Williams and Mohammed, 2009). However, little is known about the role of secondary school racial composition in perpetuating health disparities in adulthood. Though there is a body of literature examining the role of place for minority health, much of this research focuses on neighborhood segregation (Osypuk and Acevedo-Garcia, 2010; c.f. Acevedo-Garcia and Osypuk, 2008) with little attention paid to the effects of school racial composition. There is evidence that among blacks and Hispanics attending predominantly white universities, the likelihood of experiencing discrimination and its resulting emotional distress is high (McCabe, 2009). The stress of experiencing discriminatory behavior in educational settings, particularly during adolescence, could have long-term health consequences for minority youth. There is, however, a dearth of knowledge regarding how school racial composition influences race/ethnic disparities in adult health and the psychosocial pathways through which these processes occur.

In adolescence, the mechanisms through which social contexts influence health are unique given the various biological and social transitions that occur during this developmental period, including pubertal onset, the transition from primary to secondary school, and the transition from parents as primary socializing agents to peers (Crosnoe, 2000). Moreover, during adolescence, autonomy increases and individuals begin to make decisions that may have long-term effects on their health (Harris, 2010). To this end, our study extends prior research by using data from Waves I and IV of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) to examine the role of school racial composition in explaining race/ethnic differences in early adult health. Further, we address whether discrimination serves as a mechanism through which school racial composition predicts adult health. Finally, we examine the degree to which the association between school racial composition and adult health is further mediated by the social pathways through which discrimination influences adolescent social connectedness (i.e. loneliness and school attachment) and whether the deleterious effects are offset by parent support.

Background

School contexts generally reflect the larger macro system of stratification where racial/ethnic inequality, socioeconomic inequality, and discrimination are normative (Kao and Thompson, 2003; Coll, 1996). The most current 2006/7 school year data documents that whites are the most racially and economically segregated of all racial/ethnic groups; an average white student attends a school where 77% of the students are white and 32% of the students are poor. In comparison, the average black or Hispanic student attends a school where approximately 28% of students are white and 59% of students are poor (Orfield, 2009). Moreover, school segregation significantly impacts the distribution of key educational opportunities and advantages necessary for continued educational achievement.

Predominantly-minority schools, on average, have fewer resources, higher concentrations of low-income youth, and more punitive discipline policies (Darling-Hammond, 2004; Orfield and Eaton, 1996; Welch and Payne, 2010). Even so, black and Hispanic students often hold more optimistic, pro-school attitudes when they attend predominately-minority schools (Goldsmith, 2004). Thus, although attending schools with white students often garners socioeconomic and material resource advantages for minority students, attending such schools may also result in black and Hispanic students feeling marginalized and isolated because of their race/ethnicity (Feagin et al., 1996; Lewis, 2003).

School Racial Composition and Health: Psychosocial pathways to health disparities

We utilize the Integrative and Biopsychosocial Theoretical Models to examine the pathways through which secondary school racial composition influences minority youths’ early adult health. The Integrative Model posits that racial/ethnic minority youth are embedded in a stratified social hierarchy that leads to segregation in physical (e.g. school), social (e.g. peer groups), and psychological environments (e.g. emotional isolation). The lower placement of racial/ethnic minorities in this stratification system leads to poorer trajectories of well-being (Coll et al., 1996). The key stratification mechanisms through which social environments influence minority well-being include racism and discrimination (Coll et al., 1996), mechanisms that the Biopsychosocial Model of Racism as a Stressor theorizes has serious adult health consequences (Clark et al., 1999). According to the Biopsychosocial model, blacks are disproportionately exposed to environmental stimuli that are chronic sources of stress to which they react both psychologically and physiologically (Clark et al., 1999). The consequences of these race-specific stressors on health are mediated by coping responses such as feelings of isolation as well as engagement in risk behaviors that, in turn, result in physiologic responses associated with health declines (i.e. immune, neuroendocrine, and cardiovascular function; c.f. Clark et al., 1999). We merge the Integrative Model’s developmental perspective with the Biopsychosocial Model’s emphasis on black adult health to better understand the consequences of school racial composition for minority adolescents’ subsequent adult health.

There is a growing literature documenting the psychosocial consequences of school racial composition for racial/ethnic minorities. Black, Hispanic, and Asian adolescents and young adults are more likely to experience discrimination in certain school settings (McCabe, 2009; Allen, 1992; Feagin, et al., 1996). Within predominantly white settings, black and Hispanic youth are more likely to experience discrimination and racial harassment (McCabe, 2009; Allen, 1992; Feagin, et al., 1996; Juvonen et al., 2006), and report that teachers perceive them as less intelligent than whites (Lewis, 2003). Conversely, there is an expanding literature demonstrating that Asian youth experience more overt discrimination in ethnically diverse schools (Rivas-Drake et al., 2008; Fisher et al., 2000) as a result of preferential treatment given to them by their teachers (Rosenbloom and Way, 2004). Qualitative studies documenting discrimination in urban, predominantly minority schools have described the consequences for Asian youth who are stereotyped as ‘model minorities’ (Rosenbloom and Way, 2004; Conchas and Perez, 2003). Asian youth were lauded by white and Asian teachers as academically superior, thus reaping the benefits of teacher attentiveness and support, whereas teachers characterized black and Hispanic students as ‘lazy and unmotivated’ (Conchas and Perez, 2003: 53; Rosenbloom and Way, 2004). Consequently, Asian youth reported experiencing hostility and aggression from black and Hispanic youth and ambivalence from black teachers (Conchas and Perez, 2003).

An important ramification for minority students in contexts where they are the numerical minority is the elevated risk of alienation that is in part due to race-related micro-aggressions, covert expressions of racism (McCabe, 2009; Feagin et al., 1996), and overt harassment by peers in school (Rosenbloom and Way, 2004, Fisher et al., 2000). Youth who perceive discriminatory treatment by their peers and teachers report higher levels of depression and anger, lower psychological resiliency, and lower self-esteem (Seaton and Yip, 2009; Wong et al., 2003). Moreover, black and Hispanic youth who experience racism and discrimination at school are at increased risk of disengaging from school (i.e. lower school attachment; c.f. Chavous et al., 2008) and report greater loneliness (McCabe, 2009), whereas Asian youth who experience discrimination report more depressive symptoms (Rivas-Drake et al. 2008).

Social integration is essential for good health (House et al., 1988). Dimensions of social integration include perceived social isolation and the functional nature or quality of social relationships (House et al., 1988). For adolescents, loneliness (i.e. perceived social isolation) and school attachment are important aspects of social integration. Consequently, lonely adolescents have higher rates of depression, suicide attempts, and lower self-esteem (Halle-Lande et al., 2007). Moreover, loneliness in adolescence is associated with higher rates of obesity, elevated blood pressure, and higher cholesterol in adulthood (Danese et al., 2009; Caspi et al., 2006).

Minority youth may be particularly vulnerable to feelings of isolation, especially in settings where they are the numerical minority. Black and other minority youth who experience discrimination in school may de-identify from school or exhibit declines in school attachment (i.e., sense of connection or closeness to people at their school; Libbey, 2004) as a psychological coping strategy (c.f. Chavous et al., 2008) that protects them from threats to their well-being caused by negative stereotypes and low academic expectations (Aronson, 2002; Schmader et al., 2001). School attachment is associated with adolescent mental health and multiple health behaviors; more attached youth engage in fewer risky behaviors and report lower levels of distress (Giordano, 2003; McNeely and Falci, 2004; Resnick et al., 1997). Conversely, adolescents who report being less attached to their school also report higher rates of drug use, depression, and suicide ideation (Bond, 2007; Bearman and Moody, 2004; Tani et al., 2001).

Although adolescents spend more time with peers than parents, parents remain instrumental in protecting youth from social stressors or offsetting their impact (Caldwell et al., 2002; Neblett et al., 2008). A growing body of literature demonstrates that, particularly for black youth, supportive parents are crucial in protecting youth from the harmful psychological impacts of racial discrimination (Hughes et al., 2006). Among adolescents, supportive parent/offspring relationships are associated with less alcohol and tobacco use (Resnick et al., 1997) and fewer physical health complaints (Wickrama et al., 1997). Though empirical literature has long been in agreement about the importance of parental support for healthy adolescent development, the role of parent support in mediating race/ethnic disparities in adult physical health is poorly understood.

Self-rated health is an important indicator of mental and physical health and is a valid measure of general health in early adulthood (Mikolejzyk et al., 2008; Manor et al., 2001). To our knowledge, limited information exists regarding adolescent predictors of early adult self-rated health generally and adolescent pathways to race/ethnic differences in early adult self-rated health specifically. Our study applies the Integrative and Biopsychosocial Models to investigate the relationship between school racial composition and self-rated health in adulthood. We hypothesize that blacks and Hispanics who attended predominantly white schools in their youth will report worse health than their counterparts who attended predominately minority schools in their youth. Conversely, we expect Asians to experience poorer health if they attended more ethnically diverse schools. Furthermore, we hypothesize these relationships will be mediated by perceived discrimination and youths’ psychosocial responses (i.e. loneliness and school attachment) to attending predominantly white or minority schools. Finally, we expect that parent supportiveness will further attenuate the relationship between school racial composition and health as well as the relationships between loneliness, school attachment, and self-rated health.

Methods

We analyzed Wave I (1994/5) and Wave IV (2007/8) restricted data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a nationally representative sample of adolescents in grades 7 through 12 in 1994/5 (Harris et al., 2009). The Add Health sample is representative of U.S. schools with respect to region of country, urbanicity, school size, school type (private/public), and race/ethnicity. Our analysis utilized three data sources: (1) in-home interviews of the respondent in Waves I and IV, (2) in-home interview of the parent in Wave I, and (3) a self-administered questionnaire completed by the school administrator in Wave I.

We restricted our analysis to adolescents who were interviewed in Wave I and Wave IV. Approximately 908 students were excluded from the analysis due to item-missingness. After exclusions, our final analytic sample consisted of 13,538 students (7,510 non-Hispanic whites, 2,834 non-Hispanic Blacks, 2,129 Hispanics, 825 Asians, and 240 of other race/ethnicity) who were attending 132 junior and senior high schools in 1994/5.

Measures

Dependent Variable

In Wave IV, respondents were asked “In general, how is your health? Would you say excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” We coded self-rated health so that higher values reflect better health. Studies document the validity of self-rated health across all racial/ethnic groups in the U.S (c.f. McGee et al., 1999). Moreover, strong evidence suggests that race/ethnic health disparities begin to widen in the thirties (Geronimus et al., 2001; Walsemann et al., 2008), making this an excellent point in the life course to measure health, as respondents were between 24 and 34 years old in Wave IV.

Independent Variables

School Racial Composition in Wave I

We measured school racial composition as the percent of non-Hispanic white students at each school, henceforth “percent white students”. We calculated percent white students using self-reported race/ethnicity from all students interviewed in the 1994/5 in-home survey, which we aggregated to the school level using the Wave I probability weights provided by Add Health to ensure that the aggregated data were representative of the school. We chose this specification rather than using the in-school survey, which provides a full enumeration of the student body because significant measurement bias for self-reported race/ethnicity exists in the in-school survey (Perez, 2008). Values ranged from 0 to 100. To assess the reliability of our measure, we examined the correlation between our aggregated measure and administrative data on school racial composition that was available for 69 schools through the Common Core Data that was linked to Add Health via the Adolescent Health and Academic Achievement (AHAA) study in Wave III (Muller et al., 2007); the correlation was 0.99.

Perceived Discrimination at Wave I

To assess perceived discrimination at Wave I, we used separate indicators of unfair treatment and prejudice. Students were asked how much they agreed (on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1=strongly agree and 5=strongly disagree) that (1) “teachers at your school treat students fairly” and (2) “students are prejudiced”. We reverse coded the first item, such that higher values reflected greater perceptions of unfair treatment by teachers.

Social Connectedness-Isolation at Wave I

To measure school connectedness, we used three separate indicators. Students were asked how much they agreed (on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1=strongly agree and 5=strongly disagree) that (1) “you feel you are part of your school”; (2) “you feel close to people at your school”; and (3) “you are happy to be at your school”.

Respondents were asked using a 4-point Likert scale (0=never or rarely; 3=most of the time or all of the time) how often in the past seven days: (1) they felt lonely; (2) they felt that people disliked them; and (3) people were unfriendly to them. Respondents were also asked how much they agreed (on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1=strongly agree and 5=strongly disagree) that they: (1) felt loved and wanted; and (2) felt socially accepted (Cronbach’s α =.69). Factor scores derived from these five items were calculated and used to create regression factor scores. The factor scores predict the location of an individual on the factor loneliness. Thus, higher factor values represent higher levels of loneliness.

Parental Support at Wave I

Respondents were asked how much they agreed (on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1=strongly disagree and 5=strongly agree) that (1) “most of the time, your mother is warm and loving to you”; (2) “you are satisfied with the way your mother and you communicate with each other”; (3) “overall, you are satisfied with your relationship with your mother”; (4) “most of the time, your father is warm and loving to you”; (5) “you are satisfied with the way your father and you communicate with each other”; and (6) “overall, you are satisfied with your relationship with your father”. Two additional items were asked of respondents not living with their biological mother or father: (1) “how close do you feel to your biological mother?” and (2) “how close do you feel to your biological father?” Responses ranged from 1=not close at all to 5=extremely close. The eight items were summed to create a scale of parental support (Cronbach’s α =.85). Similar to the loneliness scale, regression factor scores were calculated and used to predict the location of individuals on the specific factor parental support. Higher standardized factor scores denote higher levels of parental support.

Individual-Level Covariates

We included a set of individual-level covariates that may be associated with adult self-rated health or school racial composition to account for potential confounding between school racial composition and adult self-rated health. We included age of respondent in 1994/5 as a continuous variable and gender of respondent as male or female. Respondents self-reported their race/ethnicity, which we categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic (any race), or other. We categorized respondents as immigrants if they reported being born outside of the U.S. to non-U.S. citizens. We also created a measure of family structure in 1994/5 categorized as nuclear (two biological parents), step-family (one biological and one step-parent), female-headed, extended/intergenerational family, and other. Finally, we constructed a composite measure of family SES because multivariate indices of SES are more reliable than single-item measures and doing so reduced issues with item-missingness. Family SES was calculated as the mean of standardized (z-score) measures of family poverty (i.e., parent-reported household income to federal poverty level in 1995), parental educational level (i.e., parent-reported 10-level ordinal variable ranging from “did not go to school” to “professional training beyond a 4-year degree”), and parental occupation (i.e., respondent-reported 7-level ordinal variable). The composite score was calculated for all respondents who had information on at least one of the indicators used in the composite measure. If the respondent resided with one parent, information for the one parent was used. If the respondent resided with two parents, the average of both parents’ information was calculated. Positive values represented higher levels of SES (Cronbach’s α =.66).

Measures of adolescent health status and behaviors from Wave I were included. Self-rated health was assessed using the following question: “In general, how is your health? Would you say excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”. Higher values reflect better health. Respondents who smoked at least one cigarette for 15 to 30 of the prior 30 days were categorized as regular smokers. Binge drinking was measured as drinking four (females) or five (males) drinks in a row at least once over the past 12 months. Victimization was measured as if, in the past 12 months, respondents experienced any of the following: 1) someone pulled a knife or gun on them; 2) they were shot or stabbed; 3) they were slapped, hit, kicked, or choked; or 4) they were beaten. Respondents’ Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated from self-reported height and weight using a module in Stata v11 to adjust for adolescent age and sex and which utilizes the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) obesity cutoffs. BMI scores were converted to z-scores with the LMS method developed by Cole and Green (1992). This method takes into account skewness while adjusting for anthropometric changes that happen as youth age (Vidmar et al., 2004). Finally, we categorized respondents as using substances if they reported using marijuana, cocaine, inhalants or stimulants, or other drugs in the previous 30 days.

School-Level Covariates

We created a composite measure of school SES using the same variables included in the family SES variable, but aggregated to the school level, to provide consistency across SES measures. School SES was calculated as the mean of standardized (z-score) measures of school-level poverty, school-level parental education, and school-level parental occupation with higher values representing higher levels of school SES (Cronbach’s α=.84). Additional covariates included school urbanicity (urban = central city within a CMSA or MSA; suburban = CMSA or MSA with at least 2,500 residents but not in central city, rural = all else), region (West, Midwest, South, and Northeast), school type (public versus private), and school size (small=1–400 students; medium=401–1000 students; large=1001–4000 students).

Analytic Approach

First, we began with descriptive and bivariate statistics to understand the data distribution followed by examining two-level linear models to investigate the extent to which school racial composition, perceived discrimination, and perceived social connectedness or isolation (i.e., school attachment, loneliness, and parental support) were associated with early adult health. After examining an unconditional model (not shown), with no predictors, to assess between-school variation in early adult health, we ran a model that examined the main effect of school racial composition after adjusting for school urbanicity, school sector (public versus private), school region, school size, and school SES (Model 1). We then adjusted for age, gender, immigrant status, family structure, family SES, and other correlated measures of health behaviors or health status at Wave I in Model 2. Next, to examine if the relationship between school racial composition and early adult self-rated health varied by race/ethnicity, we created a set of interaction terms between percent white students and respondent race/ethnicity, which we included in Model 3. Model 4 further adjusted for the two indicators representing perceived discrimination. Model 5 included measures of school attachment and perceived loneliness. Finally, we ran a model to determine if the effects of school racial composition were attenuated once parental support was included (Model 6). In the model building process, we also examined changes in the -2 log likelihood to assess model fit.

The equation from our final model (Model 6) for predicting early adult self-rated health is presented below.

Where Yij is the level of self-rated health at Wave IV for respondent i in school j and assumes that conditional on μ0 j, Yij to Ynj are independent; j = 1, … Jk is the number of schools included in our sample; is a vector of individual-level covariates (e.g., race/ethnicity, loneliness, parental support); is a vector of school-level covariates (e.g., percent white students) and cross-level interactions (e.g., black × percent white students); and μ0 j represents variation in intercepts between schools (i.e., between school variability) and is assumed to be randomly and normally distributed with mean zero; and εij is the random within-school variability for respondent i in school j.

To make the interpretation of the intercept more meaningful, age was centered at 16, the approximate mean age of the sample in Wave I, percent white students at a school was grand mean centered at 59%, and the individual-level and school-level covariates were centered at their respective grand means, except for gender and race/ethnicity. Next, to help with the interpretation of the regression coefficients for the variable percent white students, we transformed this variable (original variable/10) such that the reported coefficients represent a 10% increase in school racial composition rather than a 1% increase. The two-level linear models were estimated with maximum likelihood using xtreg in Stata v11. All analyses were unweighted. As such, all models included the individual (i.e., race/ethnicity) and school level (i.e., school urbanicity, school region, school sector, and school size) sampling variables. By including the variables used to sample respondents, unweighted analyses produce unbiased results (Winship and Radbill, 1994).

Sensitivity Analysis

We tested the sensitivity of our models to model specification as follows. First, we excluded schools with 0% and 100% white students to examine our results after excluding schools at the extremes of the distribution. The results were similar to those found in the full sample, but the sample was no longer representative of the school population in 1994/5. Thus, we present the findings from the full sample only. Second, we specified two-level generalized linear models using an ordered logit link and a binomial distribution via Stata’s gllamm program.

The results were comparable to the two-level linear models we present in this paper. Simulation studies have also found that comparable results can be drawn when using linear models as compared to ordered logit models when the ordinal variable has 5 or more levels (Kromrey & Redina-Gobloff, 2002). As such, we chose to present the results from the linear models since interpretation of the regression estimators is more intuitive. Finally, we considered models of racial concordance; these models indicated that attending schools where one’s racial group was the numerical majority had little effect on early adult self-rated health.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 13,538 respondents who were dispersed across 132 schools (number of respondents per school (i.e., density) ranged from 1 to 1111) in 1994/5. Respondents in our sample were predominantly white (54.4%), 6.4% were immigrants, and 52.8% were females (Table 1). In Wave I, 46.4% of respondents lived in nuclear families, the average respondent had slightly below-average family SES (M = −0.1, min = −2.3, max = 1.4), and the mean age was 16.1 years (min=11.4; max=20.0). The average respondent reported slightly higher than average agreement with feeling close to people at school (3.7), part of their school (3.8), happy to be at their school (3.7), and that students were prejudiced (3.2). Conversely, the average respondent tended to disagree with the idea that teachers treated students unfairly (2.5). On average, most respondents in 1994/5 were enrolled in large (47.9%), suburban (53.9%), public schools (92.5%) that were primarily white (58.7%) and had slightly above-average SES (M=0.2, min= −1.8, max=2.2).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, Waves I and IV, N=13,538

| Mean (SD) or %

|

|

|---|---|

| Self-Rated Health (Wave IV) | |

| Excellent | 19.6 |

| Very Good | 38.7 |

| Good | 32.7 |

| Fair | 8.1 |

| Poor | 1.0 |

| Social Connectedness (Wave I) | |

| Perceived Discrimination | |

| Students Prejudicedb | 3.2 (1.2) |

| Unfair Treatment by Teachersb | 2.5 (1.1) |

| School Attachment | |

| Part of Schoolb | 3.8 (1.1) |

| Close to People at Schoolb | 3.7 (1.0) |

| Happy to be at Schoolb | 3.7 (1.1) |

| Loneliness Scaleb | −0.0 (1.0) |

| Parental Supportb | 0.0 (1.0) |

| Individual-Level Covariates (Wave I) | |

| Age of Respondentb | 16.1 (1.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 55.5 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 20.9 |

| Hispanic | 15.7 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6.1 |

| Other | 1.8 |

| Immigrant | 6.4 |

| Female | 52.8 |

| Family Structure | |

| Nuclear | 46.4 |

| Step-Family | 9.4 |

| Female Headed Household | 15.1 |

| Extended/Intergenerational | 24.1 |

| Other | 5.0 |

| Family Socio-economic Statusb | −0.1 (0.8) |

| Respondents’ Self-Rated Healthb | |

| Excellent | 28.4 |

| Very Good | 40.3 |

| Good | 24.7 |

| Fair | 6.3 |

| Poor | 0.4 |

| Body Mass Indexb | 0.4 (1.0) |

| Regular Smoker (30 days) | 13.2 |

| Ever Binge Drink (12 months) | 25.9 |

| Ever Use Substances (30 days) | 15.1 |

| Ever Victim of Physical Violence | 14.3 |

| School-Level Covariates (Wave I) | |

| Percent Non-Hispanic Whiteb | 58.7 (35.5) |

| School Socio-economic Statusb | 0.2 (0.9) |

| School Type | |

| Private | 7.6 |

| Public | 92.5 |

| School Size | |

| Small (1–400 students) | 15.0 |

| Medium (401–1000 students) | 37.1 |

| Large (1001 – 4000 students) | 47.9 |

| Region | |

| West | 23.3 |

| Midwest | 25.7 |

| South | 38.0 |

| Northeast | 13.1 |

| Urbanicity | |

| Rural | 17.6 |

| Urban | 28.6 |

| Suburban | 53.9 |

Notes:

Variables are categorical and can be interpreted as percentages unless otherwise noted.

Continuous variable, mean reported

Bivariate Associations

We examined bivariate associations between a select number of covariates and self-rated health at Wave IV (Table 2). We found significant variation (p<.05) between all covariates and self-rated health, except for respondents’ perceptions that students were prejudiced at their school in Wave I. For example, those who reported better self-rated health in Wave IV reported lower levels of loneliness at Wave I (−0.21 among those who rated their health as excellent; 0.34 among those who rated their health as poor). Comparatively, respondents who reported better self-rated health in Wave IV also appeared to report higher levels of parental support in Wave I (0.14 among those who rated their health as excellent; −0.26 among those who rated their health as poor).

Table 2.

Estimates from Bivariate Analysis of Selected Characteristics and Self-Rated Health in Wave IV, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (N=13,538)a

| Self-Rated Health Wave IV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent n=2,654 |

Very Good n=5,235 |

Good n=4,422 |

Fair n=1,091 |

Poor n=136 |

|

|

| |||||

| Individual-Level Covariates | |||||

| Race/Ethnicityc | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 57.20 | 59.50 | 52.49 | 44.45 | 52.21 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 21.55 | 18.45 | 22.52 | 25.48 | 16.18 |

| Hispanic | 14.43 | 14.19 | 16.67 | 21.54 | 22.79 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5.24 | 6.06 | 6.54 | 6.69 | 5.25 |

| Other | 1.58 | 1.80 | 1.79 | 1.83 | 3.68 |

| Femalec | 49.85 | 52.65 | 53.87 | 55.45 | 59.56 |

| Social Integration | |||||

| Perceived Discrimination | |||||

| Students Prejudicedb | 3.11 | 3.15 | 3.13 | 3.21 | 3.02 |

| Unfair Treatment by Teachersb, d | 2.41 | 2.47 | 2.56 | 2.72 | 2.82 |

| School Attachment | |||||

| Part of Schoolb, d | 3.97 | 3.89 | 3.76 | 3.59 | 3.77 |

| Close to People at Schoolb, d | 3.78 | 3.75 | 3.63 | 3.58 | 3.62 |

| Happy to be at Schoolb, d | 3.84 | 3.76 | 3.62 | 3.51 | 3.50 |

| Loneliness Scaleb, d | −0.21 | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.34 |

| Parental Supportb, d | 0.14 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.21 | −0.26 |

| School-Level Covariates | |||||

| Percent Non-Hispanic Whiteb, d | 59.48 | 61.10 | 56.90 | 53.30 | 55.79 |

Notes:

Variables are categorical and can be interpreted as percentages unless otherwise noted; Column percentages reported.

Continuous variable, mean reported

p<.05, chi-sq test

p<.05, F-test

Two-Level Linear Models

We first examined the main effect of school racial composition on self-rated health at Wave IV in Table 3. Results from Model 1, the least restrictive model, revealed that as the percent of white students increases, respondents reported poorer self-rated health at Wave IV (b=−0.012). Adjustment for individual covariates at Wave I resulted in the attenuation of this effect (b=−0.007, p>0.05) (Model 2); individual covariates explained approximately 58% of the effect of school racial composition on self-rated health (1−[(−.012−(−.007))/−.012]). We also found similar levels of self-rated health at Wave IV between black and white respondents (b=−0.041, p>0.05), and poorer self-rated health among Hispanic (b=−0.105) and Asian (b=−0.176) respondents as compared to whites in Model 2.

Table 3.

Estimates from Two-Level Generalized Linear Model Predicting Better Self-Rated Health in Wave I, (N=13,538).a,b, c,d

| Model 1 b(SE) |

Model 2 b(SE) |

Model 3 b(SE) |

Model 4 b(SE) |

Model 5 b(SE) |

Model 6 b(SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Intercept | 3.712 (0.017)*** | 3.755 (0.090)*** | 3.740 (0.090)*** | 3.735 (0.090)*** | 3.711 (0.090)*** | 3.691 (0.090)*** |

| Individual-Level Variables | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity (Ref=White) | ||||||

| Black | −0.093 (0.026)*** | −0.041 (0.026) | −0.059 (0.027)* | −0.053 (0.027)* | −0.055 (0.027)* | −0.054 (0.027)* |

| Hispanic | −0.186 (0.029)*** | −0.105 (0.029)*** | −0.107 (0.032)*** | −0.106 (0.032)*** | −0.111 (0.032)*** | −0.110 (0.032)*** |

| Asian | −−0.114 (0.039)** | −0.176 (0.039)*** | −0.053 (0.052) | −0.055 (0.052) | −0.051 (0.052) | −0.049 (0.052) |

| Other | −0.103 (0.061) | −0.051 (0.058) | −0.045 (0.060) | −0.042 (0.060) | −0.043 (0.060) | −0.043 (0.060) |

| Female | −0.040 (0.015)*** | −0.039 (0.015)** | −0.037 (0.015)* | −0.030 (0.015)* | −0.026 (0.015) | |

| Perceived Discrimination | ||||||

| Students Prejudiced | 0.005 (0.007) | 0.010 (0.007) | 0.010 (0.007) | |||

| Unfair Treatment by Teachers | −0.028 (0.007)* | −0.016 (0.008)* | −0.014 (0.008) | |||

| School Attachment | ||||||

| Close to People at School | −0.012 (0.009) | −0.013 (0.009) | ||||

| Part of School | 0.020 (0.010)* | 0.020 (0.010)* | ||||

| Happy to be at School | 0.008 (0.009) | 0.007 (0.009) | ||||

| Loneliness Scale | −0.053 (0.008)*** | −0.047 (0.009)*** | ||||

| Parental Support Scale | 0.019 (0.008)* | |||||

| School-Level Variables | ||||||

| % NH Whitee | −0.012 (0.006)* | −0.007 (0.005) | 0.001 (0.007) | 0.001 (0.007) | −0.000 (0.007) | −0.000 (0.007) |

| School Socio-Economic Status | 0.113 (0.019)*** | 0.047 (0.017)** | 0.045 (0.017)** | 0.045 (0.017)** | 0.047 (0.017)** | 0.048 (0.017)** |

| Cross-Level Interactions | ||||||

| Black × % NH White | −0.020 (0.009)* | −0.021 (0.009)* | −0.019 (0.009)* | −0.019 (0.009)* | ||

| Hispanic × % NH White | −0.010 (0.009) | −0.010 (0.009) | −0.011 (0.009) | −0.010 (0.009) | ||

| Asian × % NH White | 0.029 (0.013)* | 0.028 (0.013)* | 0.029 (0.013)* | 0.029 (0.013)* | ||

| Other × % NH White | −0.014 (0.018) | −0.014 (0.018) | −0.013 (0.018) | −0.013 (0.018) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Level-2 Variance | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Δ-2 Log-Likelihoodf | −107.8*** | −1529.5*** | −15.9** | −14.8*** | −59.5*** | −5.4* |

Notes:

Unconditional model level 2 variance=0.15.

Covariates centered at grand means, except gender.

All models adjusted for school urbanicity, school sector (private or public), school region, school size, and health behaviors/status in 1994/5.

Models 2–6 further adjusted for age (centered at 16), gender, nativity, family structure, and family SES,

Percent white students centered at 59% and divided by 10;

Change in the -2LL contrasts Model 1 to unconditional model (not shown); Model 2 to Model 1; Model 3 to Model 2, and Model 4 to Model 3, Model 5 to Model 4, and Model 6 to Model 5.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

With the inclusion of the cross-level interaction terms (Model 3), we found a significant association between percent white students at school and self-rated health at Wave IV for black and Asian respondents. As the percentage of white students in a school increases, black respondents reported poorer self-rated health (b=−0.020) at Wave IV. However, this effect was reversed for Asian respondents (b=0.029). Given the inclusion of interactions between respondent race/ethnicity and school racial composition, the main effects of race/ethnicity in Model 3 represent differences when respondents attended schools where 59% of the student body was white. Thus, black respondents experienced poorer self-rated health (b=−0.059) and Asians reported similar levels of self-rated health (b=−0.053, p>0.05) than whites (Model 3) when attending a school with 59% white students.

Adjustment for indicators of perceived discrimination did not attenuate the effect of school racial composition for black and Asian respondents (Model 4), but estimates from Model 4 suggest that respondents who reported unfair treatment by teachers experienced poorer self-rated health at Wave IV. With the inclusion of indicators of school attachment and perceived loneliness, the effect of unfair treatment by teachers was attenuated by 57%, but the effect of school racial composition for black and Asian respondents remained similar (Model 5). Indicators of school attachment were in general unrelated to self-rated health at Wave IV with the exception of feeling part of school (b=0.020); however, greater levels of loneliness were associated with poorer self-rated health at Wave IV (b=−0.053). Although parental support at Wave I (Model 6) was associated with better self-rated health (b=0.019), the inclusion of this measure did not attenuate the association between school racial composition and early adult self-rated health.

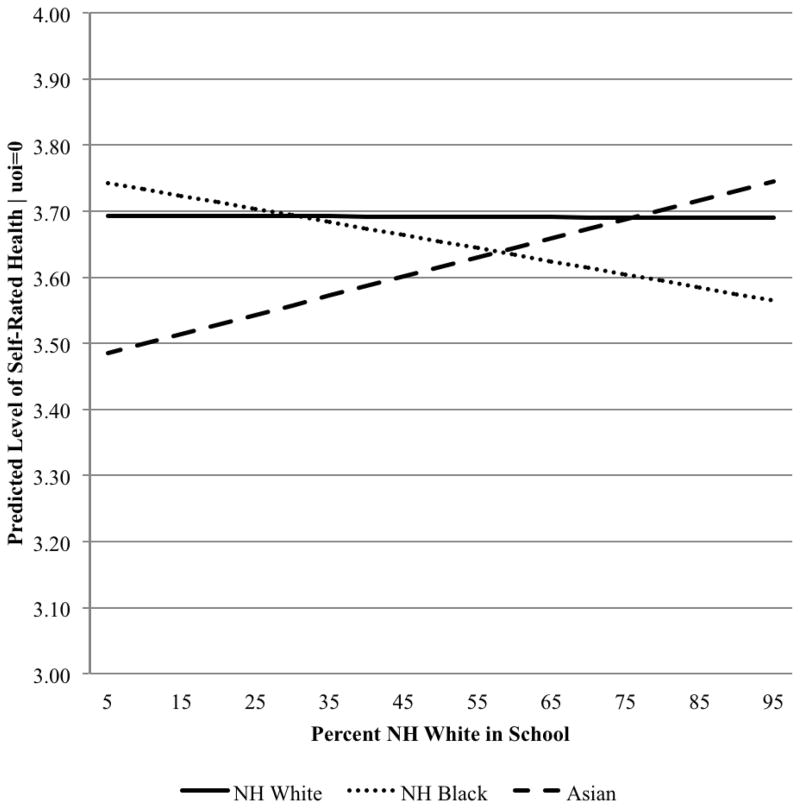

As shown in Figure 1, after controlling for individual and school characteristics included in Model 6, self-rated health at Wave IV was poorer for black respondents, but better for Asian respondents, as the percentage of white students attending their school at Wave I increased. Thus, the racial/ethnic disparity in early adult health was greatest between black and white respondents who attended schools with large percentages of white students, but smallest between Asian and white respondents who attended these same schools.

Figure 1.

Level of Predicted Self-Rated Health in Wave IV for White, Black, and Asian/Pacific Islander Respondents by Percent White Students in the School in Wave I, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (N=13,538).

Notes: Higher values represent better health. Adjusted for all covariates (Model 6). Age is centered at 16 and all covariates are centered at their grand mean (except for gender). Plotted lines represent male respondents. The lines representing Black and Asian/Pacific Islander respondents are statistically different (p<.05) from the line representing White respondents.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide preliminary evidence that secondary school racial composition has consequences for early adult health. For black respondents, attending a school with a higher percentage of white students was associated with poorer health, whereas for Asian respondents the inverse was true. Although black youth attending predominantly white schools may benefit from the higher levels of resources that accompany predominantly white schools, they may simultaneously be hampered by stereotypes about their academic capability held by their peers, teachers, and administrators (Tatum 2004). Experiencing such health-compromising stress during adolescence may lead to poor health in adulthood. Conversely, Asian youth attending predominantly minority schools may experience the stress of overt peer hostility as a consequence of teachers’ adherence to the model minority stereotype that may result in teachers’ preferential treatment of Asian students (Conchas and Perez 2003). In both instances, there could be long-term consequences for adult health.

Little research exists exploring how discrimination experiences affect subsequent health among Asian youth in predominantly white settings. However, several studies examining the relationship between school racial composition and adolescent and early adult health outcomes found little evidence that predominantly white schools have a harmful impact on Asian adolescent and adult well-being (Walsemann and Bell 2011; Walsemann et al. 2011). Although research suggests that Asians experience race related discrimination in predominantly white settings (Lee 2003; 2005), the protective nature of educational achievement and teacher support stemming from the acceptance of the model minority stereotype could offset the harmful effect of discrimination on health.

The Integrative and Biopsychosocial models suggest that discrimination is a key mechanism through which youth development and adult health are influenced (Coll et al., 1996; Clark et al., 1999). Although reports of prejudiced peers and unfair treatment by teachers did not explain the association between school racial composition and early adult health, unfair treatment by teachers was independently associated with poorer early adulthood health. There are important shortcomings in our indicators of discrimination, however. First, our discrimination measures do not assess whether youth considered their discriminatory experiences as racially motivated, which may have consequences for well-being (Branscombe et al., 1999). Nor can our study assess whether Asian youth are considered ‘perpetual foreigners,’ a persistent harmful perception that may exacerbate feelings of alienation and declines in well-being (Ng et al. 2007; Conchas and Perez, 2003). Future research should provide more specific and nuanced measures of discrimination and should assess types of discrimination unique to certain race/ethnic groups.

We proposed important social integration and support mechanisms for explaining the influence of school racial composition on race/ethnic differences in early adult health. Though our study did not find evidence that parent support or loneliness mediated the effects of school racial composition on black and Asian early adult health, both factors independently predicted early adult health. The findings for parent support point to the importance of social support for protecting youth from harmful stressors and correspond to prior literature indicating that racial/ethnic minorities who receive protective racial socialization from their parents report better mental health and emotional well-being (Neblett et al., 2008; Rivas-Drake et al., 2008).

We were unable to explain the differences in early adult health outcomes for blacks in predominantly white schools and Asians in predominantly minority schools. Nevertheless, there are unmeasured dynamics that may help explain the differences. First, ethnic identity is an important preventative buffer against racial discrimination and protective for minority health (Rivas-Drake et al., 2008; Sellers et al. 2006). Put simply, youth who a have a strong, positive attachment to their racial or ethnic background are less likely to be negatively impacted by racial discrimination (c.f. Rivas-Drake et al., 2008). For black youth in predominantly white settings, having a strong attachment to their racial group and awareness of examples that run counter to traditional stereotypes about their racial group can offset the harmfulness of potential microaggressions, although if negative stereotyping in the school environment is pervasive, it can actually hinder healthy identity development (Tatum 2004). For Asian youth strong ethnic identity is also protective against the harmful effects of discrimination, both in predominantly white and predominantly minority contexts (Rivas-Drake et al. 2008; Lee 2005). Additionally, we could not account for the extent to which minority youth receive support from peers when experiencing discriminatory experiences. There is evidence that Black youth in predominantly white schools may not only have fewer youth of similar racial backgrounds from which they can draw support but they may also have less access to diverse school curricula from which they might find positive reinforcement of their own ethnic identity (Lewis, 2003).

Our study expands upon the educational and developmental psychology literatures, which have established that the secondary school environment is particularly salient for the healthy psychological development and socioeconomic success of adolescents (Roeser et al., 2000). We also contribute to the expansive sociological literature showing that educational attainment is strongly tied to life course health (c.f. Dupre 2007; Lynch 2003). We highlight a complex pathway through which schools can subsequently contribute to health disparities beyond just educational attainment. For black youth, attending predominantly minority schools means having comparatively less school resources and lower graduation rates, both of which are strong predictors of early adult health (Gore and Aseltine, 2003; Walsemann et al., 2011). However, there appears to be a cost for black youth at predominantly white schools in that they do not report comparable health to their white counterparts in the same schools. Our results mirror research that finds that blacks do not experience the same health payoffs as whites with comparable education (Green and Darity, 2010). Moreover, though we cannot study the actual in-school dynamics, our results support findings that Asian youth experience a cost to attending more ethnically diverse schools where they may unwittingly be embedded in a setting that elevates their status as a model minority, inadvertently creating hostility among other marginalized groups (c.f. Way et al., 2008).

Though our study is innovative in examining school contextual and social pathways during adolescence that contribute to early adult health, there are limitations that should be noted. First, our study may underestimate the impact of school segregation for adult health. For example, school segregation has increased since 1994/5, when Wave I data was collected (Orfield, 2001; Orfield and Lee, 2007). Potential period effects could also be present due to the economic recession experienced in 2007/8 while Wave IV data was collected, which could potentially confound our results for adult health. Because we only measure social integration at Wave I to predict health at Wave IV, we cannot account for potential changes in support, connectedness, and discrimination. Also, due to data limitations, we were unable to disaggregate Hispanics or Asians into their respective ethnic groups. For Asians, we found in post-hoc analysis that particular subgroups were more likely to attend predominantly white schools (not shown), even after adjusting for family SES, school SES, and immigrant status. Moreover, prior research notes that health disparities vary across different Hispanic and Asian ethnic groups - variations we cannot assess (c.f. Williams et al., 2010; Chen 2005). Finally, our study is limited to the school environment; however, other social environments influence health (Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn, 2003). More research is required to examine how different social environments (e.g. schools and neighborhoods) in youth influence early adult health.

Conclusion

The goal of this study was to identify potential social and contextual pathways that contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in early adult health. Our study demonstrates that not only does school racial composition matter for minority health in adulthood, but school contexts also influence minority youth in different ways. These results point to the need for a deeper examination of how the costs of being a racial or ethnic minority in the US varies according to the complicated social and racial dynamics that individuals from different groups experience within the school setting. Several qualitative studies exploring discrimination experienced by black, Hispanic, and Asian youth in ethnically diverse schools uncover a complex story involving both peer group and teacher interactions that require further examination. Given that schools can play an instrumental role in reifying racial and ethnic stratification and perpetuating disparities in health, we recommend more systematic studies of the school related mechanisms associated with changes in early adult health. In order to address race/ethnic health disparities, research requires a better understanding of how the interplay between ethnic diversity and adolescent psychosocial responses to their social context result in long-term health outcomes.

Highlights.

Black youth in predominately white schools report poorer early adult health than white youth.

Asian youth in predominantly minority schools report poorer early adult health than white youth.

School attachment, loneliness, and parent support in adolescence are independently associated with adult health and do not mediate school racial composition effects on black and Asian health.

Discrimination does not mediate school racial composition effects on black and Asian health.

School racial composition and in-school social dynamics have consequences for health in early adulthood.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gilbert Gee and Robert Hummer for providing insightful comments on this paper. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis. This paper is part of a larger study funded by the Nation Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K01 HD 064537). All opinions and errors are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of either the helpful commentators or funding agencies sponsoring Add Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Osypuk TL. Invited Commentary: Residential Segregation and Health—The Complexity of Modeling Separate Social Contexts. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168:1255–1258. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen WR. The Color of Success: African American College Student Outcomes at Predominantly White and Historically Black Public Colleges and Universities. Harvard Educational Review. 1992;62:26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ancis J, Sedlacek W, Mohr H. Student Perceptions of Campus Climate by Race. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2000;78:180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J. Stereotype threat: Contending and coping with unnerving expectations. In: Aronson J, editor. Improving Academic Achievement: Impact of Psychological Factors on Education. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, Moody J. Suicide and Friendships among American Adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:89–95. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becares L, Nazroo J, Stafford M. The buffering effects of ethnic density on experienced racism and health. Health & Place. 2009;15:700–708. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond L, Bulter H, Thomas L, Carlin J, Al E. Social and School Connectedness in Early Secondary School as Predictors of Late Teenage Substance Use, Mental Health, and Academic Outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:357.e9–357.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving Pervasive Discrimination Among African Americans: Implications for Group Identification and Well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA, Bernat D, Sellers RM, Notaro PC. Racial Identity, Maternal Support, and Psychological Distress among African American Adolescents. Child Development. 2002;73:1322–1336. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Harrington H, Moffitt TE, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Socially isolated children 20 years later: Risk of cardiovascular disease. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:805–811. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavous TM, Rivas-Drake D, Smalls C, Griffin T, Cogburn C. Gender Matters, Too: The Influences of School Racial Discrimination and Racial Identity on Academic Engagement Outcomes among African American Adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:637–654. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MS. Cancer Health Disparities among Asian Americans. Cancer. 2005;104:2895–2902. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a Stressor for African Americans: A Biopsychosocial Model. Amerian Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole TJ, Green PJ. Smoothing reference centile curves: The LMS method and penalized likelihood. Statistics in Medicine. 1992;11:1305–1319. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conchas GQ, Perez CC. Surfing the “model minority” wave of success: How the school context shapes distinct experiences among Vietnamese youth. New Directions for Youth Development. 2003:41–56. doi: 10.1002/yd.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R. Friendships in childhood and adolescence: The life course and new directions. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2000;63:377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Risk Factors for Age-Related Disease: Depression, Inflammation, and Clustering of Metabolic Markers. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:1135–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond L. Inequality and the Right to Learn: Access to quality teachers in California’s Public Schools. Teachers College Record. 2004;106:1936–1966. [Google Scholar]

- Dupre ME. Educational Difference in Age-Related Patterns of Disease: Reconsidering the Cumulative Disadvantage and Age-as-Leveler Hypotheses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:1–15. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR, Vera H, Imani N. The Agony of Education. New York: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination Distress During Adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, Mcadoo HP. An Integrative Model for the Study of Developmental Competencies in Minority Children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimous A, Bound J, Waidman T, Colen C. Inequality in life expectancy, functional status, and active life expectancy across selected Black and White populations in the United States. Demography. 2001;38:227–251. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC. Relationships in Adolescence. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:257–281. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith PA. Schools’ Racial Mix, Students’ Optimism, and the Black-White and Latino-White Achievement Gaps. Sociology of Education. 2004;77:121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, Huang B, Schafer-Kalkhoff T, Adler N. Perceived Socioeconomic Status: A New Type of Identity That Influences Adolescents’ Self-Rated Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore S, Aseltine RH. Race and Ethnic Differences in Depressed Mood Following the Transition From High School. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:370–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TL, Darity W. Under the Skin: Using Theories from Biology and the Social Sciences to Explore the Mechanisms Behing the Black-White Health Gap. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:S36–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle-Lande JA, Eisenberg ME, Christenson SL, Neumark-Sztainer D. Social Isolation, Psychological Health, and Protective Factors in Adolescence. Adolescence. 2007;42:265–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM. An Integrative Approach to Health. Demography. 2010;47:1–22. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman C, Power C, Mattews S, Manor O. Using an interactive framework of society and lifecourse to explain self-rated health in early adulthood. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;53:1575–1585. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Social Structures and Processes of Social Support. Annual Review of Sociology. 1988;14:293–318. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson H, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Nishina A, Graham S. Ethnic diversity and perceptions of safety in urban middle schools. Psychological Science. 2006;17:393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, Thompson JS. Racial and Ethnic Stratification in Educational Achievement and Attainment. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:417–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kromery JD, Redina-Gobioff G. An empirical comparison of regression analysis strategies with discrete ordinal variables. Multiple Linear Regression Viewpoints. 2002;28:30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. Resilience against discrimination: Ethnic Idenity and Other-Group Orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. Do ethnic identity and other-group orientation protect against discrimination for Asian Americans? Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2003;50:133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ. Unraveling the “model minority” stereotype: Listening to Asian American youth. New York: Teachers College Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Children and Youth in Neighbhorhood Contexts. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AE. Race in the Schoolyard: Negotiating the Color Line in Classrooms and Communities. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Libbey HP. Measuring Student Relationships to School: Attachment, Bonding, Connectedness, and Engagement. Journal of School Health. 2004;74:274–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SM. Cohort and Life Course Patterns in the Relationship between Education and Health: A Hierarchical Approach. Demography. 2003;40:309–333. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manor O, Mattews S, Power C. Self-rated health and limiting longstanding illness: inter-relationships with morbidity in early adulthood. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30:600–607. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.3.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccabe J. Racial and Gender Microaggressions on a Predominantly-White Campus: Experiences of Black, Latina/o and White Undergraduates. Race, Gender, & Class. 2009;16:133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Mcgee DL, Liao Y, Cao G, Cooper RS. Self-Reported Health Status and Mortality in a Multiethnic U.S. Cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;149:41–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcneely C, Falci C. School Connectedness and the Transition Into and Out of Health Risk Behavior Among Adolescents: A Comparison of Social Belonging and Teacher Support. Journal of School Health. 2004;74:284–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczyk R, Brzoska P, Maier C, Ottova V, Al E. Factors associated with self-rated health status in university students: a cross sectional study in three European countries. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:215–225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, White RL, Ford KR, Philip CL, Nguyen HX, Sellers RM. Patterns of Racial Socialization and Psychological Adjustment: Can Parent Communications about Race Reduce the Impact of Racial Discrimination? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:477–515. [Google Scholar]

- Ng JC, Lee SS, Pak YK. Contesting the Model Minority and Perpetual Foreigner Stereotypes: A Critical Review of Literature on Asian Americans in Education. Review of Research in Education. 2007;31:95–130. [Google Scholar]

- Orfield G. Schools more separate: Consequences of a decade of resegregation. Cambridge, MA: Civil Rights Project at Harvard University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Orfield G. Reviving the Goal of an Integrated Society: A 21st Century Challenge. Los Angeles, CA: The Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles at UCLA; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Orfield G, Eaton SE. Dismantling Desegregation: The Quiet Reversal of Brown v Board of Education. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Orfield G, Lee C. Historic Reversals, Accelerating Resegregation, and the Need for New Integration Strategies. Los Angeles: UCLA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Osypuk TL, Acevedo-Garcia D. Beyond individual neighborhoods: A geography of opportunity perspective for understanding racial/ethnic health disparities. Health & Place. 2010;16:1113–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez AD. Who is Hispanic? Shades of ethnicity among Latino/a youth. In: Gallagher C, editor. Racism in post-race America: New theories, new directions. Chapel Hill, NC: Social Forces; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. People Like Us: Ethnic Group Density Effects on Health. Ethnicity and Health. 2008;13:321–334. doi: 10.1080/13557850701882928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon OA. Asian Americans, “Critical Mass,” and Campus Racial Climate: A CRT Case Study. In: Park CC, Goodwin AL, Lee SJ, editors. Research on the Education of Asian Pacific Americans. Information Age Publishing; (In Press) [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Al E. Protecting Adolescents From Harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Hughes D. A Closer Look at Peer Discrimination, Ethnic Identity, and Psychological Well-being Among Urban Chines American Sixth-Graders. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, Eccles JS, Sameroff AT. School as a Context of Early Adolescents’ Academic and Socio-Emotional Development: A Summary of Research Findings. The Elementary School Journal. 2000;100:443–471. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom SR, Way N. Experiences of Discrimination among African American, Asian American, and Latino Adolescents in an Urban High School. Youth & Society. 2004;35:420–451. [Google Scholar]

- Schmader T, Major B, Gramzow RH. Coping with ethnic stereotypes in the academic domain: Percieved injustice and psychological disengagement. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Yip T. School and Neighborhood Contexts, Perceptions of Racial Discrimination, and Psychological Well-being among African American Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:153–163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9356-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis RL. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CS. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist. 1997;52:613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani CR, Chavez EL, Deffenbacher JL. Peer isolation and drug use among White and non-hispanic White and Mexican American adolescents. Adolescence. 2001;36:127–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and Health: Major Findings and Policy Implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;S51:S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidmar S, Carlin J, Hesketh K, Cole T. Standardizing anthropometric measures in children and adolescents with new function for egen. Stata Journal. 2004;4:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Walsemann KM, Bell B, Goosby BJ. The Effect of School Racial Composition on Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms from Adolescence through Early Adulthood. Race and Social Problems. 2011;3:131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Walsemann KM, Bell BA. Integrated Schools, Segregated Curriculum: Effects of Within-School Segregation on Adolescent Health Behaviors and Education Aspirations. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;100:1687–1695. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.179424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsemann KM, Geronimous AT, Gee GC. Accumulating disadvantage over the life course: Evidence from a longitudinal study investigating the relationship between educational advantages in youth and health in middle-age. Research on Aging. 2008;30:227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Way N, Santos C, Niwa EY, Gervey C. To be or not to be: An exploration of ethnic identity development in context. The Intersections of Personal and Social Identities New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2008;120:61–79. doi: 10.1002/cd.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch K, Payne AA. Racial Threat and Punitive School Discipline. Social Problems. 2010;57:25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Lorenz FO, Conger RD. Parental support and adolescent physical health status: A latent growth-curve analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:149–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and Racial Disparities in Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winship C, Radbill L. Sampling Weights and Regression Analysis. Sociological Methods and Research. 1994;23:230–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The Influence of Ethnic Discrimination and Ethnic Identification on African American Adolescents’ School and Socioemotional Adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1197–1232. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]